Zdunkowski W., Trautmann T., Bott A. Radiation in the atmosphere: A course in Theoretical Meteorology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.5 The finite difference method 115

In terms of I

+

and I

−

the boundary conditions (4.106) and (4.107) can be expressed

as

(a) I

+

i

(0) + I

−

i

(0) = 2A

g

s

j=1

w

j

µ

j

I

+

j

(0) − I

−

j

(0)

+

A

g

π

µ

0

S

0

exp

−

τ (0)

µ

0

+ ε

g

B(T

g

), i = 1,...,s

(b) I

+

i

(z

t

) − I

−

i

(z

t

) = 0 (4.110)

It is convenient to define s-dimensional vectors

I

+

(z) =

I

+

1

(z)

.

.

.

I

+

s

(z)

, I

−

(z) =

I

−

1

(z)

.

.

.

I

−

s

(z)

(4.111)

Furthermore, boundary matrices A

t

, B

t

and A

g

, B

g

will be used for the upper and

lower boundary, respectively. Using these definitions equations (4.110) may be

reformulated as

A

t

I

+

(z

t

) + B

t

I

−

(z

t

) = 0

A

g

I

+

(0) + B

g

I

−

(0) =

A

g

π

µ

0

S

0

exp

−

τ (0)

µ

0

+ ε

g

B(T

g

)

1

.

.

.

1

(4.112)

By writing (4.110b) as

s

j=1

δ

ij

I

+

j

(z

t

) − δ

ij

I

−

j

(z

t

)

= 0, i = 1,...,s (4.113)

it may be easily seen that the elements of the boundary matrices A

t

and B

t

are given

by

A

t,ij

= δ

ij

, B

t,ij

=−δ

ij

, i = 1,...,s, j = 1,...,s (4.114)

Analogously we find for the lower boundary condition

A

g,ij

= δ

ij

− 2 A

g

w

j

µ

j

, B

g,ij

= δ

ij

+ 2 A

g

w

j

µ

j

, i = 1,...,s, j = 1,...,s

(4.115)

116 Quasi-exact solution methods for the RTE

The system of matrix equations with (2K + 3)s equations to be solved in the

FDM can then be formulated in block tridiagonal form as

B

g

A

g

−EA

1

E

−EB

2

E

−EA

3

E

−EB

4

E

.

.

.

−EA

2K −1

E

−EB

2K

E

−EA

2K +1

E

A

t

B

t

I

−

1

I

+

1

I

−

2

I

+

3

I

−

4

.

.

.

I

+

2K −1

I

−

2K

I

+

2K +1

I

−

2K +1

=

X

g

X

1

X

2

X

3

X

4

.

.

.

X

2K −1

X

2K

X

2K +1

X

t

(4.116)

In view of (4.106) the (s × s) block matrix elements A

k,ij

(k odd) and B

k,ij

(k even)

in index form are given by

A

k,ij

=

z

β

− z

α

µ

i

k

ext

(z

k

)δ

ij

− k

sca

(z

k

)w

j

P

+

ij

(z

k

)

k = 1, 3, 5,...,2K + 1, i = 1,...,s, j = 1,...,s

B

k,ij

=

z

k

µ

i

k

ext

(z

k

)δ

ij

− k

sca

(z

k

)w

j

P

−

ij

(z

k

)

k = 2, 4, 6,...,2K , i = 1,...,s, j = 1,...,s

(4.117)

For odd k ≥ 3wehavetotakez

β

= z

k+1

, z

α

= z

k−1

.Fork = 1 and k = 2K + 1we

require z

β

= z

2

, z

α

= z

1

and z

β

= z

2K +1

, z

α

= z

2K

, respectively. The components

of the vectors X

k

are

X

k,i

=

k

sca

(z

k

)

k

ext

(z

k

)

µ

0

µ

i

S

0

4π

P

+

i0

(z

k

)

exp

−

τ (z

k+1

)

µ

0

− exp

−

τ (z

k−1

)

µ

0

+

z

β

− z

α

µ

i

k

abs

(z

k

)B(z

k

)

k =1, 3, 5,...,2K + 1, i = 1,...,s

X

k,i

=

k

sca

(z

k

)

k

ext

(z

k

)

µ

0

µ

i

S

0

4π

P

−

i0

(z

k

)

exp

−

τ (z

k+1

)

µ

0

− exp

−

τ (z

k−1

)

µ

0

k = 2, 4, 6,...,2K , i = 1,...,s

(4.118)

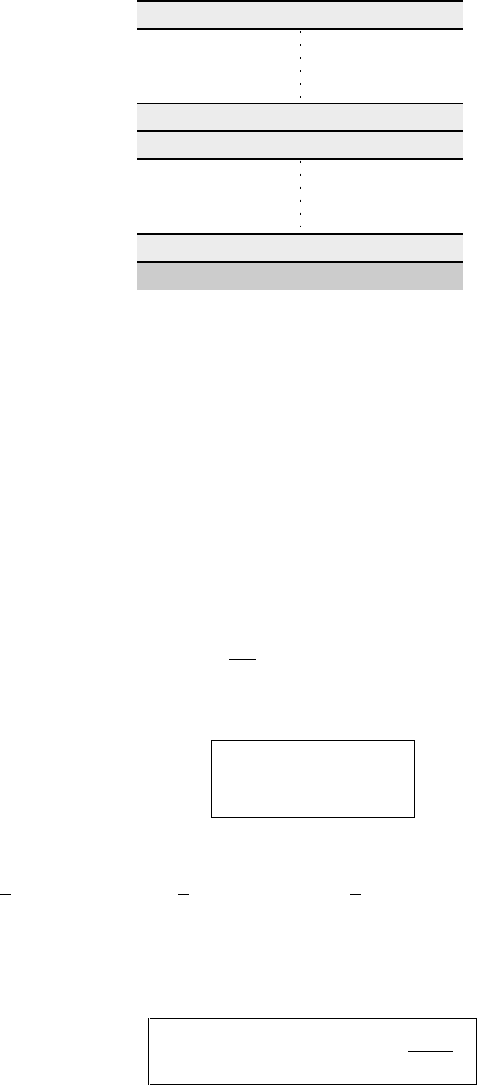

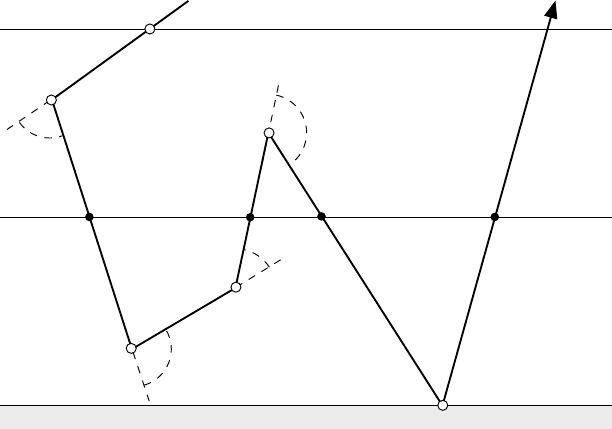

4.5 The finite difference method 117

I

+

2K+1

I

−

2K+1

A

k,ij

I

+

2k+1

B

k,ij

I

2k

I

+

1

I

−

1

Layer

2K

2k +1

2k

1

z

1

z

2

z

2k

z

2k+1

z

2k+2

z

2K

z

2K+1

ε

g

A

g

−

Fig. 4.8 Model atmosphere and assignment of the vectors I

+

, I

−

, and the block

matrix elements A

k,ij

and B

k,ij

.

The vectors X

g

, X

t

are abbreviations for the right-hand sides of the boundary

conditions (4.112). Figure 4.8 depicts the arrangement of the various vector and

matrix quantities for the FDM.

4.5.3 Computation of mean radiances and flux densities

Once we have found the solutions for the vectors I

+

(z

k

), I

−

(z

k

), k = 1,...,2K + 1

we may easily compute the internal diffuse radiation field at all levels z

k

. The mean

radiance is defined as

¯

I (z

k

) =

1

4π

2π

0

1

−1

I (z

k

,µ)dµ dϕ (4.119)

and can be directly obtained from I

+

(z

k

)

¯

I (z

k

) =

s

j=1

w

j

I

+

j

(z

k

)

(4.120)

Here we have used

1

2

1

−1

I (z,µ) dµ =

1

2

0

−1

I (z,µ)dµ +

1

2

1

0

I (z,µ)dµ =

s

j=1

w

j

I

+

j

(z)

(4.121)

The total mean radiance is given by the sum of the mean diffuse radiance and the

direct beam

¯

I

tot

(z

k

) =

¯

I (z

k

) + S

0

exp

−

τ (z

k

)

µ

0

(4.122)

118 Quasi-exact solution methods for the RTE

The up- and downwelling diffuse flux densities can be computed from

E

+

(z

k

) = 2π

1

0

µI (z

k

,µ)dµ = 2π

s

j=1

w

j

µ

j

I

+

j

(z

k

) + I

−

j

(z

k

)

E

−

(z

k

) = 2π

0

−1

µI (z

k

,µ)dµ

= 2π

s

j=1

w

j

µ

j

I

+

j

(z

k

) − I

−

j

(z

k

)

(4.123)

and the total downwelling flux density is

E

−,tot

(z

k

) = 2π

s

j=1

w

j

µ

j

I

+

j

(z

k

) − I

−

j

(z

k

)

+ µ

0

S

0

exp

−

τ (z

k

)

µ

0

(4.124)

Utilizing (4.123) the diffuse net flux density is given by

E

net

(z

k

) = 2π

1

−1

µI (z

k

,µ)dµ = E

+

(z

k

) − E

−

(z

k

) = 4π

s

j=1

w

j

µ

j

I

−

j

(z

k

)

(4.125)

To obtain the total net flux density we have to add the direct radiation, cf. (2.134),

yielding

E

net,tot

(z

k

) = E

net

(z

k

) − µ

0

S

0

exp

−

τ (z

k

)

µ

0

(4.126)

4.6 The Monte Carlo method

The Monte Carlo method (MCM) is based on the direct physical simulation of the

scattering process for the transfer of solar or thermal radiation in the atmosphere. In

the MCM a very large number of model photons enters the medium in consideration

(entire atmosphere or cloud elements). We envision a model photon to represent

a package of real photons. Neglecting the effect of atmospheric refraction, the

straight line paths of these photons between particles interacting with the radiation

is changed by scattering processes. The method requires the calculation of a large

number of photons propagating in a particular direction as they are passing a certain

test surface. From these counts we obtain the radiance as a function of position.

This permits us to compute physically relevant quantities such as flux densities for

arbitrarily oriented test surfaces, the mean radiance field, and heating rates due to

the (partial) absorption of model photons within the medium. It is very important to

realize that one has to use a sufficiently high number of such model photons so that

for the particular radiative quantity of interest a reliable statistics is achieved. If the

4.6 The Monte Carlo method 119

statistics does not satify this requirement one can simply continue the simulation

by increasing the total number of photons modeled until some accuracy criterion

is met.

The MCM has the chief advantage that one can treat arbitrarily complex prob-

lems. For example, it is relatively easy to determine the radiative transfer through

a three-dimensional spatial volume partially filled with cloud elements. In contrast

to analytical methods based on the numerical solution of the differential or integral

form of the RTE, the MCM has no difficulty at all in accounting for the horizontal

and/or vertical inhomogeneity of the optical parameters. Therefore, radiances or

flux densities can be computed at each location within a specified medium. The only

real but decisive disadvantage limiting the applicability of the MCM is related to

the statistical nature of the simulation process which, in certain situations, requires

an excessively large amount of computer time.

To give an example, the accuracy with which a certain quantity can be determined

increases only with the square root of total number of photons processed. Thus it is

very difficult to reach with MCM an accuracy limit below, say, 0.1%. In addition,

one has to make sure that a reliable random number generator is employed. If this

is not the case the computed radiance for a specific direction, for example, cannot

be determined very accurately. A good random number generator provides a large

number of significant decimal places for any random number between 0 and 1 and

also is able to generate a long random sequence before repetition occurs. For some

strategic choices to select a good random number generator the reader is referred

to Press et al. (1992). The MCM has been proven to be a very valuable research

tool for many applications which presently cannot be treated by other methods.

4.6.1 Determination of photon paths

For simplicity we will only discuss the determination of photon paths for a homoge-

neous plane–parallel medium of horizontally infinite extent. Let us assume that the

upper boundary of the medium is uniformly illuminated by parallel solar radiation.

For simplicity thermal radiation will not be treated in the discussion that follows.

At the lower boundary of the atmosphere we will assume isotropic reflection of the

ground with albedo A

g

. Let us consider a model photon reaching the ground. The

energy fraction 1 − A

g

of the model photon will be absorbed by the ground while

the remaining part is reflected.

As stated above, a model photon is assumed to represent a package of real

photons. The initial energy of the model photon is found by dividing the solar

energy in a certain spectral interval per unit area and unit time by the total number

of model photons used in the simulation. If an interaction with an absorbing gas

molecule or aerosol particle takes place, as expressed by the single scattering albedo

120 Quasi-exact solution methods for the RTE

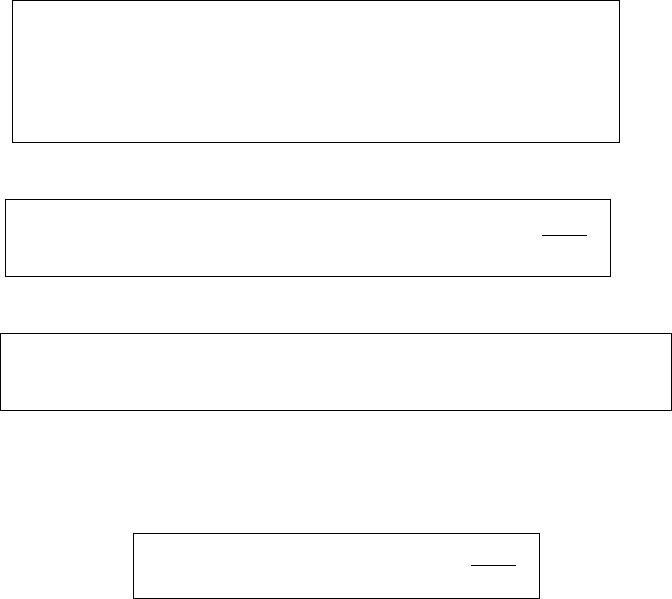

ϕ

l

i

j

k

x

y

z

P

l+1

(x

l+1

, y

l+1

, z

l+1

)

P

l

(x

l

, y

l

, z

l

)

∆s

l

ϑ

l

Fig. 4.9 Definition of the coordinates of two arbitrary interaction points P

l

and

P

l+1

.

ω

0

, the fraction 1 −ω

0

is lost by the model photon. Scattering changes the flight

direction only, but it conserves energy.

An arbitrary photon trajectory can be defined as follows: let P

0

be the point of

entrance of the photon as it enters the atmosphere through the upper boundary. The

distance from P

0

to the first interaction point P

1

will be called s

0

, and the distance

between two successive points P

l

and P

l+1

is s

l

. The direction of flight of the test

photon along the distance s

l

will be expressed by the zenith and azimuth angles ϑ

l

and ϕ

l

. By introducing a fixed Cartesian coordinate system whose z-axis is pointing

towards the zenith, see Figure 4.9, we find the coordinates (x

l+1

, y

l+1

, z

l+1

) of the

point P

l+1

as

x

l+1

=x

l

+ s

l

sin ϑ

l

cos ϕ

l

, y

l+1

=y

l

+ s

l

sin ϑ

l

sin ϕ

l

, z

l+1

=z

l

+ s

l

cos ϑ

l

(4.127)

To begin with, we will ignore the effect of gaseous absorption, but we will admit

particle absorption. Let us assume that the test photon is located at point P

l

with

coordinates (x

l

, y

l

, z

l

) where scattering occurs. Now the photon will travel the

distance s

l

to point P

l+1

where the next scattering interaction with the medium

takes place. Due to the scattering event at P

l

, the new direction of the photon path

may be expressed by selecting the local zenith and azimuth scattering angles ϑ

l

and

ϕ

l

as shown in Figure 4.9. We will not yet specify the type of scattering, but simply

follow the zig-zag path of the model photon through the atmosphere.

The entire atmosphere is discretized by a set of reference levels z

j

, ( j =

0,...,J ) where z

0

= z

g

and z

J

= z

t

denote the ground and the top of the atmo-

sphere, respectively. On its path through the atmosphere the test photon will intersect

the level z

j

as shown in Figure 4.10. We will label the intersection points with the

symbol D

i, j

whereby the index i denotes the number of the departure point P

i

after

4.6 The Monte Carlo method 121

ϑ

0

, ϕ

0

ϑ′

1

, ϕ′

1

∆

s

0

∆

s

1

,

ϑ

1

,

ϕ

1

∆

s

2

, ϑ

2

, ϕ

2

∆s

3

, ϑ

3

, ϕ

3

∆

s

5

, ϑ

5

, ϕ

5

∆

s

4

, ϑ

4

, ϕ

4

ϑ′

3

, ϕ′

3

ϑ′

2

, ϕ′

ϑ′

4

, ϕ′

4

P

0

P

1

P

2

P

3

P

4

P

5

D

1,j

D

3,j

D

4,j

D

5,j

z

t

z

j

z

g

E

2

Fig. 4.10 Trajectory of an arbitrary test photon.

the previous scattering process. As a computational step we store the direction of

flight for all test photons as they pass z

j

. In Section 4.6.2 we will briefly describe

how this information can be used to obtain radiative fluxes and radiances at all

reference levels. If a photon will escape to space we will use the symbol ‘E’ to

designate this particular event.

Figure 4.10 gives an example trajectory of a test photon through the atmosphere.

The photon enters at the top of the atmosphere at point P

0

. The angle of incidence is

(ϑ

0

,ϕ

0

). At points P

1

through P

4

the photon is scattered from the incident direction

(ϑ

l−1

,ϕ

l−1

) to the new directions (ϑ

l

,ϕ

l

). The angles (ϑ

l

,ϕ

l

) measure the local

zenith and azimuthal angles of scattering with respect to the direction of incidence

at point P

l

. At point P

5

a particular event occurs, that is isotropic reflection and

partial absorption at the ground. The pair of angles (ϑ

r

,ϕ

r

) = (ϑ

5

,ϕ

5

) is used to

describe this reflection process. The figure also illustrates the intersection points

D

i, j

which are used for photon counting at the reference level z

j

.

The flight distances s

l

can be determined from Beer’s law, cf. (2.31). According

to (2.32) for a homogeneous medium with extinction coefficient k

ext

the transmis-

sion of photons traveling the distance s is given by

T (s) = exp(−k

ext

s) (4.128)

Recall that k

ext

is wavelength dependent, i.e. k

ext

= k

ext,ν

, so that Monte Carlo

simulations have to be carried out for several wavelengths separately to derive

wavelength-integrated radiative quantities.

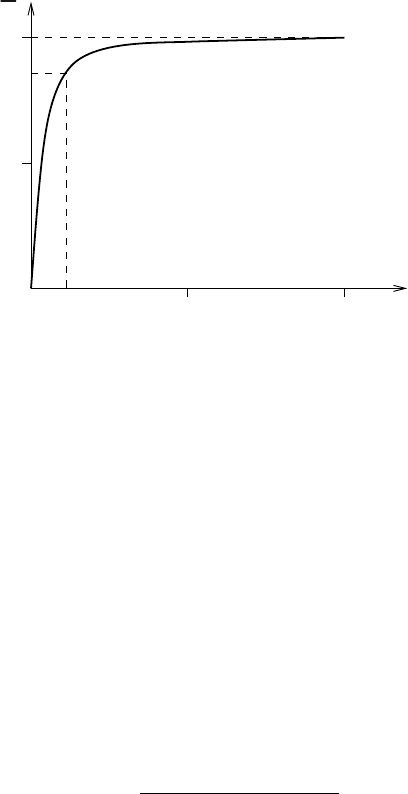

122 Quasi-exact solution methods for the RTE

0

0.5

1

90° 180°

P

R

ϑ

ϑ′ ϑ

Fig. 4.11 Determination of the local zenith angle ϑ

1

for scattering.

In Chapter 2 we found that the transmission for a path s can be interpreted as

the probability that the photon travels the distance s before the next scattering or

absorption process occurs. Therefore, by choosing in (4.128) for the transmission

T (s) a random number R

t,0

between 0 and 1 we may determine the path length

s = s

0

. In this manner we find the coordinates (x

1

, y

1

, z

1

) of the first interaction

point P

1

.

So far the test photon flew along the direction (ϑ

0

,ϕ

0

) of the direct solar beam.

Due to scattering at P

1

the test photon will now travel in a new direction as given

by the local scattering angles (ϑ

1

,ϕ

1

), see Figure 4.10. The local zenith angle for

scattering ϑ

1

can be determined from the specified phase function P(cos ϑ ) in the

following way. The probability that a test photon is scattered into the interval (0,ϑ

)

is given by the probability distribution function

¯

P(ϑ

) =

ϑ

0

P(cos ϑ) sin ϑ dϑ

π

0

P(cos ϑ) sin ϑ dϑ

(4.129)

Figure 4.11 illustrates schematically in which way the probability distribution func-

tion

¯

P(ϑ

) depends on ϑ

. As soon as a particular phase function P(cos ϑ) is chosen

the function

¯

P(ϑ

) can be determined by numerical integration. Now we choose

a random number R

ϑ,1

between 0 and 1 which picks a certain value for

¯

P(ϑ

1

).

Numerical inversion of the graph, depicted in Figure 4.11, leads to the scattering

angle ϑ

1

.

The local azimuth angle for scattering can be found in a similar way. Owing

to the rotational symmetry of P(cos ϑ

1

), see Figure 1.18, for a constant value

of ϑ

1

the phase function is independent of the azimuth angle ϕ

measured in a

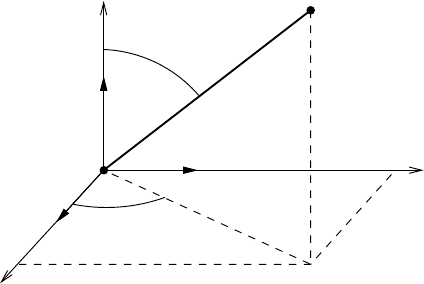

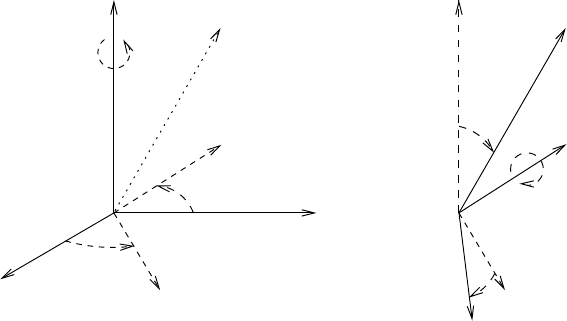

4.6 The Monte Carlo method 123

(

ϑ

0

ϑ

0

i

j

k

i

j

i

′

j

′

k

k

′

i

(a) (b)

ϑ

0

, ϕ

0

)

(ϑ

0

, ϕ

0

)

ϕ

0

ϕ

0

˜

˜

˜

˜

Fig. 4.12 Rotation of the (i, j, k) system about the angles ϕ

0

(a) and ϑ

0

(b) yielding

the (i

, j

, k

) system.

plane perpendicular to the direction of incidence. Thus we obtain ϕ

1

by selecting

a random number R

ϕ,1

from the interval [0, 2π ). Now we have found the local

scattering angles (ϑ

1

,ϕ

1

) at point P

1

which are defined with respect to the direction

of incidence (ϑ

0

,ϕ

0

) of the test photon at this point.

In the next step we need to determine the new flight direction (ϑ

1

,ϕ

1

) with respect

to the fixed Cartesian coordinate system. Let us introduce a new Cartesian system

at point P

1

defined by the unit vectors (i

, j

, k

). This primed coordinate system is

oriented so that k

points along the direction (ϑ

0

,ϕ

0

). This can be achieved by first

rotating the system (i, j, k) by an angle ϕ

0

about the z-axis yielding an intermediate

(

˜

i,

˜

j,

˜

k) system. This intermediate coordinate system will then be rotated about the

˜

j-axis by an angle ϑ

0

giving the final (i

, j

, k

) system. Analytically the two rotations

are given by

(a)

˜

i = i cos ϕ

0

+ j sin ϕ

0

˜

j =−i sin ϕ

0

+ j cos ϕ

0

˜

k = k

(b)

i

=

˜

i cos ϑ

0

−

˜

k sin ϑ

0

j

=

˜

j

k

=

˜

i sin ϑ

0

+

˜

k cos ϑ

0

(4.130)

Figure 4.12 depicts the two rotations about ϕ

0

and ϑ

0

. Substituting (4.130a) into

(4.130b), using matrix notation, yields the transformation formula for (i

, j

, k

)as

function of the original (i, j, k)

i

j

k

=

cos ϑ

0

cos ϕ

0

cos ϑ

0

sin ϕ

0

−sin ϑ

0

−sin ϕ

0

cos ϕ

0

0

sin ϑ

0

cos ϕ

0

sin ϑ

0

sin ϕ

0

cos ϑ

0

i

j

k

(4.131)

124 Quasi-exact solution methods for the RTE

Denoting in (4.131) the matrix elements by A

i, j

we may write

i

k

=

3

n=1

A

kn

i

n

, k = 1, 2, 3 (4.132)

where here and in the following we identify i = i

1

, j = i

2

and k = i

3

.

At P

1

we will define a third coordinate system with double-primed unit vectors

(i

, j

, k

) where the unit vector k

points into the flight direction (ϑ

1

,ϕ

1

) of the

test photon after the scattering event. Two successive rotations by the angles ϕ

1

and ϑ

1

transform the primed coordinate system into the double-primed system. In

analogy to (4.131) we find

i

j

k

=

cos ϑ

1

cos ϕ

1

cos ϑ

1

sin ϕ

1

−sin ϑ

1

−sin ϕ

1

cos ϕ

1

0

sin ϑ

1

cos ϕ

1

sin ϑ

1

sin ϕ

1

cos ϑ

1

i

j

k

(4.133)

or

i

k

=

3

n=1

A

kn

i

n

, k = 1, 2, 3 (4.134)

Combination of (4.132) with (4.134) leads to

i

k

=

3

n=1

3

m=1

A

kn

A

nm

i

m

, k = 1, 2, 3 (4.135)

Finally, we need a fourth coordinate system (i

∗

, j

∗

, k

∗

) resulting from the rotation

of the fixed coordinate system (i, j, k) in such a way that k

∗

points in the photon’s

new direction (ϑ

1

,ϕ

1

)atP

1

. From (4.131) we obtain again

i

∗

j

∗

k

∗

=

cos ϑ

1

cos ϕ

1

cos ϑ

1

sin ϕ

1

−sin ϑ

1

−sin ϕ

1

cos ϕ

1

0

sin ϑ

1

cos ϕ

1

sin ϑ

1

sin ϕ

1

cos ϑ

1

i

j

k

(4.136)

Obviously, both unit vectors k

∗

and k

are identical. Before the scattering event

occurs at point P

1

the photon travels in direction k

, after the scattering process its

new direction is k

. Therefore, by comparing (4.135) for k = 3 with the last row

of (4.136) we find the identities

sin ϑ

1

cos ϕ

1

=

3

n=1

A

3n

A

n1

, sin ϑ

1

sin ϕ

1

=

3

n=1

A

3n

A

n2

, cos ϑ

1

=

3

n=1

A

3n

A

n3

(4.137)