Xin Q. Diesel Engine System Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

580 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

9.6 Analytical valvetrain system design and

optimization

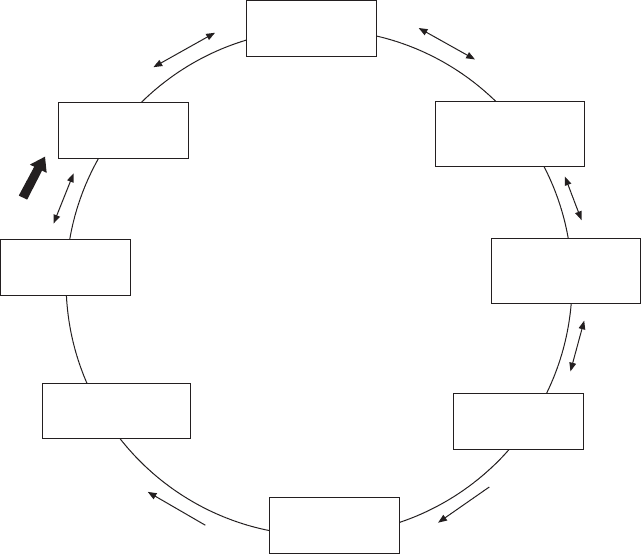

Analytical valvetrain design refers to using advanced simulation tools in

each of the following design steps to optimize the relationship between the

parameters in the valvetrain system. The scope of the valvetrain system

design is illustrated in Fig. 9.22. The key steps in the valvetrain design are

summarized as follows.

1. Select an appropriate target of valvetrain no-follow speed by the analysis

of vehicle driving and engine motoring or braking operation.

2. Use engine cycle simulation to determine the optimum valve event

duration, valve timing, and valve overlap size based on the best trade-off

between low engine speeds and high speeds. This needs to be conducted

in a coupled analysis with turbocharger matching since engine delta P

has a direct impact on gas exchange and the reverse valve ow. The

effect of valve recession on the combustion chamber ‘K-factor’ also

needs to be considered.

Spring design

Cam design

Engine

performance

Camshaft torsional

vibration

Camshaft load

analysis

Valve and piston

motion

Interactive optimized design of

valvetrain system

Valvetrain

Kinematics and

dynamics

Contact stresses,

friction, wear,

lubrication

(Start)

9.22 Concept of valvetrain system optimization.

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 580 5/5/11 11:59:07 AM

581Advanced diesel valvetrain system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

3. Determine the gas loading from the cylinder and the port acting on the

valvetrain by engine cycle simulation based on the preliminary valve

lift.

4. Select a preliminary exhaust valve spring preload based on the engine

ring and braking requirements. Select a preliminary valve spring rate

based on the dynamic simulation of valve acceleration.

5. Simulate the effect of gas loading on valvetrain vibration.

6. With given valve timing, valvetrain stiffness and weight, valve size and

valvetrain lash, optimize the following design parameters all together

in the valvetrain system by using a cam design tool and a valvetrain

dynamics simulation model to meet all the design criteria: the maximum

valve lift, rocker arm ratio, cam acceleration shape, cam base circle

radius, roller radius of the follower, cam radius of curvature, valve spring

preload, and spring rate. For example, the cam base circle radius should

be maximized within the allowable limits of space and weight. This

helps reduce the cam stress and maximize the breathing performance.

Higher rocker ratio results in higher cam force and cam stress. Lower

rocker ratio requires higher cam lift (for a given valve lift), higher cam

acceleration, and smaller radius of curvature at the cam nose.

7. Conduct valve spring design optimization on the spring diameter, the

coil diameter and the number of coils to maximize the spring natural

frequency.

8. Re-iterate from steps 2 to 7 until satisfactory trade-offs between all the

design parameters are obtained.

It should be apparent that valvetrain design is very complex due to the large

number of design parameters involved and the complex interactions among

them. An iterative process or even DoE optimization is often required.

Constructing the parametric design charts with a graphical design method is

very powerful to enhance the understanding of the parametric relationships

(e.g., Fig. 9.17 for the cam and Fig. 9.21 for the valve spring). More

information on valvetrain architecture design is provided by Jacques (1997),

Clarke and Innes (1997), and Buuck and Hampton (1997). Valvetrain system

design optimizations are presented by Seidlitz (1990), Ernst et al. (1993),

and Keribar (2000).

9.7 Variable valve actuation (VVA) engine

performance

9.7.1 The need for variable valve actuation (VVA)

In the conventional xed-cam valvetrain, the camshaft controls the intake

and exhaust valves. Valve timing, valve lift, and event duration are all xed

values specic to the camshaft design. The optimum valve timing is usually

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 581 5/5/11 11:59:07 AM

582 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

a compromise between different engine operating conditions (e.g., different

speeds or loads), and the optimum is determined to achieve a high volumetric

efciency or a low BSFC at a selected working condition. Engine valve ow

directly affects the breathing of the engine cylinder and the thermodynamic

cycle process of the engine. Air and fuel ows consist of the energy ows

of the internal combustion engine. Modern diesel engines are equipped

with electronically-controlled exible fuel injection systems and air/gas/

EGR control valves. Variable geometry turbochargers are also widely used

in production engines to regulate gas ows. The only part in the air system

left for revolutionary rather than evolutionary change is the valvetrain. An

electronically-controlled air management variable valve actuation (VVA)

system is highly desirable for modern diesel engines.

Like the expectation for variable compression ratio for optimum engine

performance without the compromise in efciency at different operating

conditions throughout the working range of the engine, a exible variation

in engine valve actuation in crank angle resolution has been a dream of

engine designers since the era of steam engines more than a century ago.

In fact, the rst study on VVA for internal combustion engines dates back

to as early as 1902 when Louis Renault conceived a simple VVA device

for a spark ignition engine. However, only in the last twenty years has the

engine industry experienced a rapid progress in VVA research, evidenced

by a drastic increase in the number of publications and patents, and the

materialization in production of spark ignition engines. This fast growth is

primarily the result of the advent of electronic engine controls applied to

VVA devices as well as market pressure on fuel economy improvement.

Various forms of VVA have been commonly used in today’s gasoline

engines in automotive production since the 1980s. The VVA application to

diesel engines has lagged behind. The biggest reason is that the conventional

gasoline engine relied on throttled operation at part load where the use of

VVA to eliminate or reduce the pumping loss due to intake throttling to

improve fuel economy can be easily justied. Intake throttle reduces the

cylinder pressure during the intake stroke. The cylinder pressure difference

between the exhaust stroke and the intake stroke forms the pumping loss.

The diesel engine inherently runs without the throttle and has a narrower

engine speed range (e.g., up to 3000 rpm for HD diesel and 4500 rpm for

LD diesel). Therefore, the benet of using VVA for the diesel engine has

traditionally been believed to be far more limited than the gasoline engine.

The questions on the benets of VVA for the diesel engine have often focused

on the cost–benet ratio for valve timing optimization and other advanced

design features such as engine compression brake.

Future advanced diesel engine technologies require a new look at the

potential of VVA. These include pumping loss reduction, HCCI combustion,

cylinder deactivation, engine brake, reconciliation between the engine valves

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 582 5/5/11 11:59:07 AM

583Advanced diesel valvetrain system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

(with the control in crank angle resolution) and air system control valves

(with the control in engine cycle resolution), and valve timing optimization.

The driving forces for diesel VVA are usually fuel economy improvement,

cost reduction via consolidating all air ow control features, and customer

demands for special features such as low-speed torque, reduced turbocharger

lag during low-speed light-load ‘tip-in’ transient accelerations, and engine

compression brake.

9.7.2 Classification of VVA

VVA generally refers to the ability to vary some or all of the following:

valve opening and closing timing or valve event duration, maximum valve

lift, and the rising rate of valve opening and closing. Although numerous

patents exist for VVA, the VVA technology can be classied into two groups

with various complexities: (1) the devices using camshafts (e.g., cam phase

shifter or phaser, cam lobe switcher, cam-driven mechanical VVA with

variable tappets or rockers, cam-based ‘lost-motion’ VVA, variable cam lobe

contour, or the ‘3-D’ cam); and (2) camless devices (e.g., electro-hydraulic,

electro-magnetic, electro-mechanical, pneumatic). VVA can also be classied

into VVT (variable valve timing) and VVL (variable valve lift) according

to the functionality.

An example of cam phase shifter is that the intake and exhaust cams are

located on separate camshafts in a double-overhead-cam valvetrain, and

the phase relationship and the valve overlap period can be varied between

the two sets of cams. Cam phase shifters are widely used in the gasoline

engine VVA. Camless VVA is more suitable for diesel engines due to its

versatile features in crank-angle-resolution air management. The camless

engine can achieve any valve event at any crank angle locations to any

valve lift position and hold it for any duration, thus exibly optimizing the

engine performance. In camless VVA, the traditional valvetrain (camshaft,

pushrods, lifters, rocker arms, and valve springs) is replaced by small and

fast electronically-controlled actuators.

More detailed classications of VVA systems and the introduction to

their design mechanisms are given by Stone and Kwan (1989). Dresner and

Barkan (1989a) classied VVA into 15 basic types of concepts.

9.7.3 Design challenges of VVA

The benets of VVA on the gasoline engine have been well established,

and the current development focus is to reduce the cost and the weight, and

improve the reliability of the VVA mechanisms. Better reliability can be

achieved by reducing complexity and valve seating velocity (e.g., with soft

landing), improving the accuracy and the repeatability of valve timing and

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 583 5/5/11 11:59:07 AM

584 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

valve event, and ensuring no collision between the valve and the piston. The

performance at low engine oil pressures and temperatures is also another

design challenge for the hydraulic-driven VVA systems.

The parasitic loss of the VVA system is generally higher than that of the

conventional cam-driven valvetrain. A low friction design is critical for any

VVA system in order to avoid negating the fuel economy benets obtained

from the better gas exchange processes of the VVA. For example, in the

camless electro-hydraulic valvetrain, the energy consumption is proportional

to the maximum valve lift generated. A low lift can be used at low speeds/

loads in order to reduce the energy consumption of the valvetrain without

a signicant negative impact on engine breathing and fuel economy.

9.7.4 Interaction of VVA with other air system

components

The valve timing effect on internal combustion engine performance is discussed

in detail by Asmus (1982), Stas (1999), Thring (1990), and Leonard et al.

(1991). VVA technologies for both gasoline and diesel engines are extensively

reviewed by Gray (1988), Stone and Kwan (1989), and Dresner and Barkan

(1989a, 1989b). Camless engines and their performance are elaborated by

Mardell and Cross (1988), Schechter and Levin (1996), Pischinger et al.

(2000), Salber et al. (2001), Tai et al. (2002), Schernus et al. (2002), and

Picron et al. (2008). A physics-based volumetric efciency model has been

introduced by Turin et al. (2008). Moreover, a thermodynamic second-law

analysis applied to VVA has been conducted by Anderson et al. (1998).

There is a wealthy body of literature addressing engine valve timing and

VVA performance. However, no study has been conducted to address the

theoretical relationship between VVA and other air system components.

The air system in this book refers to the turbocharger, the EGR system, the

manifolds, and the valvetrain. In diesel engine system design, it is important to

understand the role of valve timing and VVA in the entire air system so that

a wise system-level design solution can be selected to reconcile or simplify

the functionality between different components and avoid redundancy. This

section provides a theoretical analysis to address the relationship among

several air system technologies such as VVA, cylinder deactivation, air

control valves, EGR, and turbocharging.

The operation of the engine valves affects the number of strokes (e.g.,

two-stroke or four-stroke operation), effective engine displacement (e.g., via

cylinder deactivation by disabling the valve lift), effective engine compression

ratio (i.e., via IVC timing change), effective engine expansion ratio (i.e., via

EVO), volumetric efciency (via either valve event duration or effective valve

opening area), and eventually the engine in-cylinder thermodynamic cycle

process. The air/gas control valves in the engine gas ow network circuit and

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 584 5/5/11 11:59:07 AM

585Advanced diesel valvetrain system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

the turbocharger also affect the engine air ow through their roles outside the

cylinders at engine cycle resolution. Their effects are different from VVA on

air/EGR ow and pumping loss. However, the valvetrain and the cylinder

can be viewed as a lumped element, characterized by volumetric ef ciency,

in the gas ow network where the valvetrain essentially behaves as ow

restriction ori ces. The engine air ow rates and pressures are determined

by all the ow restriction ori ces in the ow network. For example, the

intake manifold boost pressure increases when the downstream intake valve

ow area reduces by the Miller cycle with early IVC. The exhaust manifold

pressure increases when the downstream turbine ow area reduces. The

pressure built up is also related to the air/gas ow rate through the ori ce.

For example, closing the intake throttle reduces the engine air ow rate so

that the intake manifold pressure becomes very low in front of the engine

intake valve ori ce.

The impact of valvetrain and VVA designs on engine performance can best

be understood through the roles of volumetric ef ciency, pumping loss and

EGR, driving capability in the four core equations presented in the air system

theory in Chapter 4, namely, equation 4.40 (engine volumetric ef ciency),

4.44 (EGR circuit pressure drop), 4.47 (turbocharger power balance) and 4.57

(turbine ow). These four core equations determine the engine air ow rate

and the pumping loss. The roles of different air system design and control

parameters, including any competing technologies, can be clearly comprehended

via the parametric relationships revealed in these four equations.

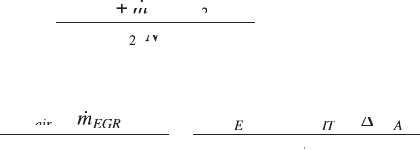

The intake manifold air–EGR mixture non-trapped volumetric ef ciency

h

vol

of a four-stroke internal combustion engine given by equation 4.40 in

Section 4.4 is shown as follows:

h

vo

l

ai

rE

GR

a

gas

aE

E

mm

ai

mm

ai

rE

mm

rE

TR

a

TR

a

pN

aE

pN

aE

V

E

V

E

=

2(

+

mm +mm

rE

mm

rE

+

rE

mm

rE

)

rE

)

rE

GR

)

GR

mm )mm

rE

mm

rE

)

rE

mm

rE

2

TR

2

TR

pN

2

pN

)

)

This equation can be rearranged in the following form:

2(

+

)

=

(

–

2

)

)

mm

+mm +

)mm )

R

N

Vp

(Vp(

pp

ai

mm

ai

mm

rE

)

rE

)

mm

rE

mm

+mm +

rE

+mm +

)mm )

rE

)mm )

GR

)

GR

)

gas

E

vo

lE

Vp

lE

Vp

pp

IT

pp

C

h

DD

ppDDpp

– pp – DD – pp –

pp

IT

ppDDpp

IT

pp

AC

CACC

AACA

CACACCAC

a

T

)

2

T

2

T

9.30

where N

E

is the engine speed, V

E

is the effective engine displacement, T

2a

is

the intake manifold gas temperature, p

2a

is the intake manifold pressure, p

2

is the compressor outlet pressure, Dp

IT

is the pressure drop associated with

the intake throttle, and Dp

CAC

is the pressure drop of the charge air cooler.

Equation 9.30 shows that in order to reach a given air and EGR ow rate

requirement, the following ve technologies need to match well (shown on

the right side of equation 9.30): valvetrain design (h

vol

), engine displacement

(e.g., cylinder deactivation), turbocharging (p

2

), intake throttle (Dp

IT

), and

air/EGR charge cooling (T

2a

).

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 585 5/5/11 11:59:08 AM

586 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

The pressure drop and the opening duration of the intake and exhaust

valves largely affect the volumetric ef ciency. Fukutani and Watanabe (1979)

indicated that volumetric ef ciency could be correlated to a mean intake

Mach number and a Mach index. When the Mach number approaches 0.5,

the volumetric ef ciency decreases drastically because the ow becomes

choked during part of the intake stroke. In general, it is always desirable

to have a large valve ow area and a high port ow coef cient in order to

minimize pumping loss and increase volumetric ef ciency.

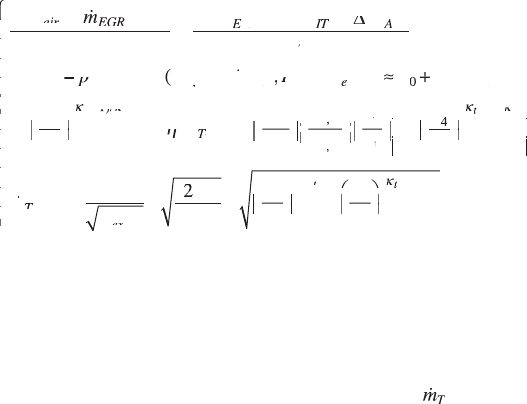

The four core equations of the engine air system are presented as follows:

2(

+

)

=

(

–

2

)

)

mm

+mm +

)mm )

R

N

Vp

(Vp(

pp

ai

mm

ai

mm

rE

)

rE

)

mm

rE

mm

+mm +

rE

+mm +

)mm )

rE

)mm )

GR

)

GR

)

gas

E

vo

lE

Vp

lE

Vp

pp

IT

pp

C

h

DD

ppDDpp

– pp – DD – pp –

pp

IT

ppDDpp

IT

pp

AC

CACC

AACA

CACACCAC

a

nE

GR

out

dE

GR

EG

RE

EGREEG

GRc

ool

T

pp

EGRi

pp

EGRi

nE

pp

nE

fC

mT

EG

mT

EG

RE

mT

RE

EGREEG

mT

EGREEG

)

nE

pp

nE

–

nE

pp

nE

=

(,

dE

(,

dE

GR

(,

GR

fC(,fC

RE

,

RE

RE

mT

RE

,

RE

mT

RE

2

T

2

T

,

dE,dE

dE

(,

dE,dE

(,

dE

mT

mT

erOu

eerOue

t

EG

R

EGREG

CT

CC

m

p

p

cc

)+

CC)+CC

1–

+

01

CC

01

CC

)+

01

)+

CC)+CC

01

CC)+CC

2

2

1

(–

cc

(–

cc

1)

cc

1)

cc

/

cc

/

cc

)+ª)+

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

kk

cc

kk

cc

(–

kk

(–

cc

(–

cc

kk

cc

(–

cc

1)

kk

1)

cc

1)

cc

kk

cc

1)

cc

/

kk

/

cc

/

cc

kk

cc

/

cc

hh

CT

hh

CT

h

CT

h

CT

TC

TTCT

m

ech

T

C

pT

pC

m

c

c

T

T

p

,

pT,pT

pC,pC

3

T

3

T

1

T

1

T

1–

m

Ê

Ë

Á

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

ˆ

¯

˜

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

Ê

Ë

Á

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

ˆ

¯

˜

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

Ê

Ë

Á

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

ˆ

¯

˜

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

444

3

(–

1)

/

3

3

=0

·

·

p

mA

= mA=

p

RT

3

RT

3

tt

(–

tt

(–

1)

tt

1)

/

tt

/

TT

mA

TT

mA

= mA=

TT

= mA=

ex

RT

ex

RT

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

È

Î

Í

È

Í

È

Í

Î

Í

Î

Í

Í

Í

˘

˚

˙

˘

˙

˘

˙

˚

˙

˚

˙

˙

˙

kk

(–

kk

(–

1)

kk

1)

/

kk

/

tt

kk

tt

(–

tt

(–

kk

(–

tt

(–

1)

tt

1)

kk

1)

tt

1)

/

tt

/

kk

/

tt

/

mA

mA

222

– 1

·

–

4

3

2/

4

3

(+

1)

/

k

k

kk

(+

kk

(+

k

t

t

p

p

p

p

tt

(+

tt

(+

tt

kk

tt

kk

(+

kk

(+

tt

(+

kk

(+

kk

tt

kk

p

tt

p

t

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

Ê

kk

Ê

kk

tt

Ê

tt

kk

tt

kk

Ê

kk

tt

kk

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

kk

ˆ

kk

tt

ˆ

tt

kk

tt

kk

ˆ

kk

tt

kk

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ÏÏÏ

Ì

Ô

ÏÏÏ

Ô

ÏÏÏ

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ì

Ô

Ì

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ó

Ô

Ì

Ô

Ì

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ô

Ó

Ô

Ó

Ô

Ô

Ô

9.31

Note that these four core equations can be used to solve for any four unknowns,

either hardware design parameters or performance parameters. Equation

9.31 shows that in order to meet a target requirement of air and EGR ow

rates, the following four unknowns can be solved with all the remaining

parameters given as known inputs: turbine wastegating

()

()

()

()m()

T

()

T

()

, EGR valve

opening (C

d,EGR

), intake manifold pressure p

2

, and turbine inlet pressure p

3

.

It is apparent that if the input assumptions of intake throttle (Dp

IT

) or valve

timing (h

vol

) are changed, a new set of solutions will be obtained and its

corresponding engine delta P will be different. Therefore, whether VVA

can replace intake throttle or wastegating in functionality depends on the

solutions obtained as such.

It should be noted that the change in volumetric ef ciency (e.g., via IVC

or valve overlap) affects the location of the engine operating point on the

compressor map and hence the compressor ef ciency because the reciprocal

of volumetric ef ciency basically re ects the slope of the point on the

compressor map. Such an in uence of VVA on turbocharger matching can

make the technology comparison mentioned above complicated. Usually, full

numerical simulation such as using GT-POWER is required to analyze the

problem. Gray (1988) reported that the variations in IVC timing and valve

overlap helped improve turbocharger matching and reduce fuel consumption

throughout the whole load range for non-EGR engines.

If the purpose of VVA is for power/torque capability, turbocharging can

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 586 5/5/11 11:59:09 AM

587Advanced diesel valvetrain system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

be viewed as one of the alternatives to VVA. This is because the valve

timing can be optimized for low-speed performance (e.g., with small valve

overlap or early IVC), and high turbocharged boost pressure can be used

to compensate for the lower volumetric ef ciency at high speeds (Stone

and Kwan, 1989). However, if the purpose of VVA is to reduce BSFC,

turbocharging and VVA are different technologies that cannot substitute

each other. The fundamental reason is that the equivalent ow restriction

‘ori ces’ of the VVA and the turbocharger are found at different locations

in the engine gas ow network and hence function differently in regulating

the gas ows and pressures.

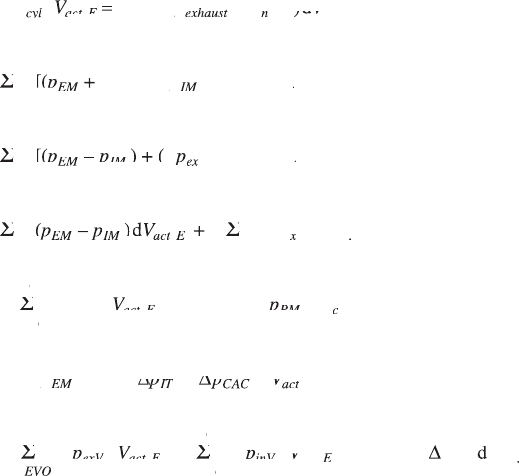

Once the solution to equation 9.31 is obtained, pumping loss needs to be

calculated in order to evaluate the impact of the given technology on BSFC.

The pumping loss work is given by the integral of the p–V diagram in the

pumping strokes at 360–720° crank angle as follows (or represented by the

area enveloped by the p–V curve shown in Fig. 4.4 in Chapter 4):

360°

,

=

360°

72

0°

d

(

720

∞

Ú

d =d

pV

d pVd

pp

(pp (

cyl

pV

cyl

pV

ac

d

ac

d

pV

ac

pV

d pVd

ac

d pVd

tE

,tE,

d

tE

d

pp

exhaus

pp

ti

pp

ti

pp

– pp–

ti

– pp–

S

f

ntak

nntakn

ea

ntakeantak

ct

E

V

ea

V

ea

)d

ea

)d

ea

,

=D

D

=D =D

[(

=D[(=D

=D+ =D

)

– (

)]

d

=

360°

72

0°

S

=DS=D

f

pp

=Dpp=D

[(pp[(

=D[(=Dpp=D[(=D

=D+ =Dpp=D+ =D

pp

DppD

– (pp – (

– pp –

V

pp

EM

pp

=Dpp=D

EM

=Dpp=D

ex

pp

IM

pp

in

ac

V

ac

V

t

,,

E

=D

D

=D =D

[(

=D[(=D

)

=D) =D

=D+ =D

(

=D( =D

+

)]

d

=

360°

72

0°

S

=DS=D

f

pp

=Dpp=D

[(pp[(

=D[(=Dpp=D[(=D

=D– =Dpp=D– =D

pp

DppD

( pp(

=D( =Dpp=D( =D

+ pp+

V

pp

EM

pp

=Dpp=D

EM

=Dpp=D

IM

=D

IM

=D

pp

ex

pp

( pp(

ex

( pp(

in

ac

V

ac

V

t

,,

E

=D

=D =D

(–

)

d

360°

72

0°

,

=

SS

=DSS=D

=D(–=DSS=D(–=D

=D )=DSS=D )=D

=D(–=D )=D(–=DSS=D(–=D )=D(–=D

=Dd =DSS=Dd =D

ff

=

ff

=

360°

ff

360°

pp

(–pp(–

)pp )

(– )(–pp(– )(–

=D(–=DSS=D(–=Dpp=D(–=DSS=D(–=D

=D )=DSS=D )=Dpp=D )=DSS=D )=D

=D(–=D )=D(–=DSS=D(–=D )=D(–=Dpp=D(–=D )=D(–=DSS=D(–=D )=D(–=D

Vp

=DVp=D

d Vpd

,

Vp

,

=DSS=DVp=DSS=D

=Dd =DSS=Dd =DVp=Dd =DSS=Dd =D

=D+ =DSS=D+ =DVp=D+ =DSS=D+ =D

pp

EM

pp

(–pp(–

EM

(–pp(–

=D(–=DSS=D(–=Dpp=D(–=DSS=D(–=D

EM

=D(–=DSS=D(–=Dpp=D(–=DSS=D(–=D

IM

)

IM

)

=D )=DSS=D )=D

IM

=D )=DSS=D )=D

Vp

ac

Vp

d Vpd

ac

d Vpd

=Dd =DSS=Dd =DVp=Dd =DSS=Dd =D

ac

=Dd =DSS=Dd =DVp=Dd =DSS=Dd =D

Vp

tE

Vp

d Vpd

tE

d Vpd

,

Vp

,tE,

Vp

,

=Dd =DSS=Dd =DVp=Dd =DSS=Dd =D

tE

=Dd =DSS=Dd =DVp=Dd =DSS=Dd =D

EVO

EVC

ex

xV

exxVex

ac

tE

V

ac

V

ac

d

,

tE,tE

9.32

+D

D

+D +D

d

+

d

D dD

=

,

S

+DS+D

S

f

IV

O

IVOIV

IV

C

IVCIV

Va

d

Va

d

ct

d

ct

d

E

d

E

d

ValveClose

d

a

pV

d pVd

in

pV

in

Va

pV

Va

d

Va

d pVd

Va

d

pV

dpV d

D dDpVD dD

PM

pV

PM

d

PM

dpV d

PM

d

a

pV

a

ct

cctc

E

,

=

(

+

)d

=

360°

720°

2,

+

2,

+

2,

)d

2,

)d

S

f

pp

(pp (

– pp –

pp

2,

pp

2,

2,

pp

2,

V

2,

V

2,

pp

EM

pp

2,

pp

2,IT2,

pp

2,

2,

pp

2,

IT

2,

pp

2,

2,CA2,

2,Ca2,

)d

2,

)d

Ca

)d

2,

)d

2,

V

2,Ca2,

V

2,

2,ct2,

E

DD

+ DD+

2,

DD

2,

ppDDpp

+ pp+ DD+ pp+

2,

pp

2,

DD

2,

pp

2,

+

2,

+ pp+

2,

+ DD+

2,

+ pp+

2,

+

2,

pp

2,IT2,

pp

2,

DD

2,

pp

2,IT2,

pp

2,

+D

+D

+D +D

d

d

+D d+D

,

=

,

SS

+DSS+D

+DSS+D

d SSd

+Dd +DSS+Dd +D

ff

=

ff

=

ff

EVO

ff

EVC

ac

d

ac

d

d SSd

ac

d SSd

tE

d

tE

d

,tE,

d SSd

tE

d SSd

IV

O

IVOIV

IV

C

IVCIV

Va

ct

pV

d pVd

SSpVSS

d SSd pVd SSd

exV

pV

exV

SS

exV

SSpVSS

exV

SS

ac

pV

ac

d

ac

d pVd

ac

d

d SSd

ac

d SSd pVd SSd

ac

d SSd

pV

dpV d

in

pV

in

d

in

dpV d

in

d

Va

pV

Va

d

Va

dpV d

Va

d

EEE

ValveClose

d

ac

tE

pV

PM

pV

PM

ac

pV

ac

+

d

pV dpV

PM

pV

PM

d

PM

pV

PM

,

tE,tE

S

D

dD d

pV dpVDpV dpV

where p

cyl

is the in-cylinder pressure, V

act,E

is the total engine displacement of

the active cylinders, f is the crank angle, p

exhaust

and p

intake

are the in-cylinder

pressure during the exhaust and intake strokes, respectively; p

EM

and p

IM

are

the instantaneous exhaust and intake manifold pressures, respectively; Dp

ex

and Dp

in

are the pressure drops across the exhaust and intake valves/ports/

manifolds, respectively; Dp

exV

and Dp

inV

are the pressure drops across the

exhaust and intake valves during the valve opening events, respectively; and

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 587 5/5/11 11:59:11 AM

588 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

Dp

PM

is the pressure losses in the intake and exhaust ports and manifolds

during the period of valve closure.

Equation 9.32 shows that the pumping loss is related not only to the intake

throttle pressure drop, but also to the valve ow pressure drops and the valve

opening duration (e.g., from IVO to IVC). The valve ow pressure drop is

related to the effective valve ow area. A larger valve ow area results in

a smaller pressure drop due to less restrictive ow. This is the reason why

the cam ow area needs to be maximized with aggressive cam acceleration.

When the valve ow area is small, volumetric efciency becomes low due

to high ow losses. The valve opening duration affects the amount of the

ow through the engine and thus also directly affects volumetric efciency.

If the valve event duration is too short, the mass ow rate will be too low in

equation 9.30 and thus the volumetric efciency will be low. Moreover, if the

valve event duration is too long, reverse ow will occur and the volumetric

efciency will also be low. More information on pumping loss denition on

the p-V diagram can be found in Shelby et al. (2004).

It should be noted that the intake manifold volumetric efciency is inherently

related only to the valvetrain and manifold designs. It is not affected by the

operation of intake throttle. When a VVA device with early IVC is used, the

volumetric efciency can become very low due to the very short intake valve

duration. However, the pumping loss can become very little if the intake

throttle is not closed, according to equation 9.32. In fact, this can be viewed

as an example of using an intake VVA to replace the intake throttle at the

part-load operation in a naturally aspirated gasoline engine. Although the

availability loss of throttling at the throttle valve itself is small, the resulting

engine pumping loss due to the throttling can be rather large. Therefore, in

principle any throttling in the engine is an indicator of high pumping loss

and should be avoided.

Pumping loss consists of two parts: the engine delta P (the rst term in

equation 9.32) and the ow restrictions related to volumetric efciency. The

second part can be further split into two portions: (1) the losses related to

valve event durations (the second and third terms in equation 9.32); and (2)

the losses associated with the ports and manifolds. Volumetric efciency

affects pumping loss differently via the valve ow restriction and the valve

event duration. If the valve ow area is too restrictive, the large pressure

drop across the valve results in a reduction in volumetric efciency and an

increase in pumping loss (i.e., expanding the pumping loss area shown in

Fig. 4.4 vertically). If the valve event duration is very short, the resulting low

volumetric efciency leads to a reduction in pumping loss (i.e., shrinking the

pumping loss area shown in Fig. 4.4 horizontally). The design modication

that reduces the ow restriction for a given valve ow duration (e.g., larger

valve ow area in a cam or VVA) results in an increase in volumetric

efciency and a decrease in the valve ow pumping loss. However, the

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 588 5/5/11 11:59:11 AM

589Advanced diesel valvetrain system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

designs affecting the valve event duration (e.g., cam or VVA timing) may

increase both volumetric efciency and the valve ow pumping loss. One

extreme example is that in cylinder deactivation the volumetric efciency

of the deactivated cylinders is zero and their pumping loss is also zero.

The link between valvetrain design and turbocharging is the intake

manifold pressure. Note that a higher volumetric efciency means a lower

intake manifold pressure and possibly less pumping loss because a lower

engine delta P can be created by a larger turbine area in order to reach the

same air ow requirement. Therefore, the net effect of valve timing change

on BSFC depends on the balance between the pumping losses caused by the

engine delta P and the valve ows.

Finally, it should be noted that BSFC (i.e., power loss) and engine gas

ow rate (i.e., volumetric efciency) are two independent different design

criteria (e.g., reected by the trade-off between BSFC and NO

x

) in valve

timing or VVA optimization. The topic can be a multi-objective optimization.

If achieving high ow rate is the design objective (e.g., for meeting emissions

or controlling the exhaust manifold gas temperature), different valve timing

designs need to be compared on volumetric efciency at the same intake

manifold pressure. On the other hand, if achieving low BSFC is the objective,

pumping losses need to be compared at the same engine ow rate.

9.7.5 Gasoline engine VVA performance

Overview of gasoline engine VVA

Before the discussion of diesel engine VVA performance, a summary of the

gasoline (spark ignition) engine VVA is benecial in order to understand

their differences. The majority of VVA research has been conducted at the

part-load conditions on the gasoline engine with the primary purposes of

eliminating or reducing the use of intake throttle, and optimizing the valve

timing to increase the volumetric efciency within a wide range of engine

speed to improve the low-speed torque. Both the port-fuel-injection and the

direct injection gasoline engines are partially throttled at part load to meet

the operational requirement of the exhaust aftertreatment catalyst. In this

case, VVA can replace the intake throttle to reduce fuel consumption. At the

full load, the engine is usually run with the intake throttle fully open.

Over the next few decades the following three technologies will have

decisive impacts on the gasoline engine in air ow controls to improve fuel

economy: (1) throttleless operation by using VVA to achieve charge control

or load control to replace the intake throttle; (2) stratication by direct

injection; and (3) variable displacement by cylinder deactivation.

Important research work on gasoline engine VVA performance has been

conducted by Tuttle (1980), Elrod and Nelson (1986), Ma (1988), Payri et

al. (1988), Saunders and Abdul-Wahab (1989), Ahmad and Theobald (1989),

Diesel-Xin-09.indd 589 5/5/11 11:59:11 AM