Xin Q. Diesel Engine System Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

136 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

Oxidation

Oxidation damage is caused by repeated formation of an oxidation layer at

the crack tip and its rupture. The rate of growth of oxidation layer thickness

is proportional to the square root of time in the absence of cyclic loading;

and the rate of growth is much higher in cyclic loading conditions where

the oxidation layer repeatedly breaks and the fresh surface is exposed to

the environment (Ogarevic et al., 2001). The details of the modeling of

oxidation damage and creep damage were provided by Su et al. (2002) in

their investigation of cylinder head failures.

2.8.5 Fatigue

Material fatigue

Fatigue is a slow cycle-number-dependent irreversible process of plastic

deformation when a material is under cyclic loading. It is a progressive and

localized type of structural damage. Fatigue is caused by stress levels less

than the ultimate tensile strength or even below the yield strength. Fatigue

is embodied as macroscopic crack initiation and propagation induced by

microscopic trans-granular fracture in the material. The causes and processes

of fatigue can be explained by fracture mechanics as several stages: crack

nucleation and initiation, crack growth, and ultimate ductile failure. Material

behavior such as cyclic hardening, creep and plasticity has an important

impact on fatigue. Fatigue is different from creep. Creep is embodied by

the deformation and growing of the cavities inside the material primarily at

high temperatures caused by inter-granular fracture. Creep is dependent on

time rather than the number of loading cycles.

Fatigue life

Fatigue life is dened as the number of loading (stress) cycles of a specied

character that a specimen sustains before failure of a specied nature occurs.

The number of cycles is related to engine speed. It can be converted to

equivalent durability hours. Fatigue life is affected by cyclic stresses, residual

stresses, material properties, internal defects, grain size, temperature, design

geometry, surface quality, oxidation, corrosion, etc. The fatigue life of a

component under the following different fatigue mechanisms can be ranked

from low to high as: thermal shock, high temperature LCF, low temperature

LCF, and HCF. In the assessment of the risk of fatigue failure, it may be

assumed that the component is safe for an innite number of cycles if it

does not show failures after more than ten million cycles.

The total fatigue life is equal to the life of crack formation and crack

propagation. Fatigue life is dependent on the cycle history of the loading

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 136 5/5/11 11:44:50 AM

137Durability and reliability in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

magnitude since crack initiation requires a larger stress than crack

propagation.

The fatigue life of the component can be determined by the strain, stress,

or energy approach. Fatigue is a very complex process affected by many

factors. It is usually more effective to use a macro phenomenological method

to model the effects of fatigue mechanisms on fatigue life rather than using

a microscopic approach.

Fatigue strength and fatigue limit

Fatigue strength is dened as the stress value at which fatigue failure occurs

after a given fatigue life. Fatigue limit is dened as the stress value below

which fatigue failure occurs when the fatigue life is sufciently high (e.g.,

10–500 million cycles). Ferrous alloys and titanium alloys have a fatigue

limit below which the material can have innite life without failure. However,

other materials (e.g., aluminum and copper) do not have such a fatigue

limit for innite life and will eventually fail even with small stresses. For

these materials, a number of loading cycles is chosen as a design target of

fatigue life.

Thermal fatigue

Thermal fatigue is a fatigue failure with macroscopic cracks resulting from

cyclic thermal stresses and strains due to temperature changes, spatial

temperature gradients, and high temperatures under constrained thermal

deformation. Thermal fatigue may occur without mechanical loads. The

constraints include external ones (e.g., bolting load) and internal ones (e.g.,

temperature gradient, different thermal expansion due to different materials

connected). Compressive stresses are produced by the bolting load at high

temperatures, or generated in the material having high coefcient of thermal

expansion. Tensile stresses are produced when the component cools, or

generated in the material having low coefcient of thermal expansion.

Thermal stresses are produced by cyclic material expansion and contraction

when temperature changes under geometric constraints. A crack may develop

after many cycles of heating and cooling. The failure indicator or criterion

of thermal fatigue is usually strain rather than stress. Thermal fatigue life is

determined mainly by material ductility rather than material strength.

Thermal fatigue can be HCF or LCF, depending on the magnitude of

thermal stress compared to the yield strength of the material. Thermal fatigue

life can be predicted by using either stress (for HCF) or plastic strain (for

LCF) as a criterion. The thermal fatigue in engine applications usually refers

to the thermo-mechanical fatigue problems where thermal fatigue plays a

dominant role.

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 137 5/5/11 11:44:50 AM

138 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

Anisothermal fatigue can sometimes be more damaging than isothermal

fatigue. Isothermal fatigue occurs when tension or compression cycles are

imposed at a constant temperature. Anisothermal fatigue occurs when the

component temperature and strain vary simultaneously. An engine may

operate at isothermal conditions in steady state for a long period of time (e.g.,

in stationary power application or durability testing). Automotive engines

often encounter anisothermal fatigue during largely varying thermal cycles.

Anisothermal fatigue is more complex to model than isothermal fatigue

because of the varying temperatures within the cycle.

The mechanical properties of the material deteriorate with time when the

material is exposed above certain level of temperature. The ultimate strength

of the material decreases due to the aging of mechanical properties at high

temperatures. This aggravates the occurrence of plastic deformation in thermal

fatigue. Experimental work has conrmed that the maximum component

temperature in a thermal cycle (e.g., cycling from high engine speed-load

modes to low speed-load modes) has a much greater inuence on thermal

fatigue life than the minimum or cycle-average component temperatures.

The maximum temperature is also more important than the temperature

range of the cycle for the reason that the fatigue-resistance property of the

material deteriorates quickly at high temperatures. This means in engine

system design the maximum gas temperature and heat ux should be used

as design constraints in most cases.

Thermal fatigue life can be improved by reducing the temperature and

temperature gradient or alleviate the geometric constraints. For example,

reducing metal wall thickness can reduce the gas-side surface temperature

and thermal expansion hence increase fatigue life. Using slots or grooves

in the component may eliminate the constraints for thermal expansion.

Thermo-mechanical fatigue

The thermal fatigue in engines is usually accompanied by both thermal and

mechanical stresses. The compressive and tensile stresses often exceed the

yield strength of the material in much thermo-mechanical fatigue. Three

typical engine components subjected to thermo-mechanical fatigue failures

are the cylinder head, the piston, and the exhaust manifold.

Thermo-mechanical fatigue (either HCF or LCF) failures consist of

the accumulated damage due to three major mechanisms: mechanical or

thermal fatigue; oxidation and degradation; and creep. Oxidation is caused

by environmental changes. Degradation refers to chemical decomposition

and the deterioration of material strength due to temperature change or

mechanical fatigue. Material aging also affects damage but as a secondary

effect.

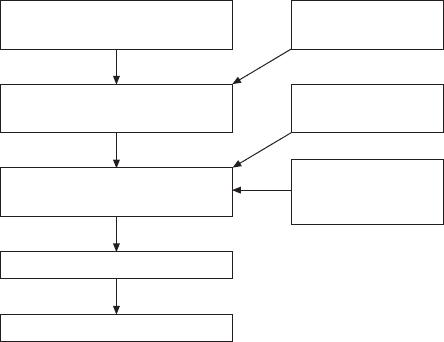

Engine system design, component design and durability testing are three

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 138 5/5/11 11:44:50 AM

139Durability and reliability in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

closely related areas to achieve successful design and prediction of thermo-

mechanical fatigue life of the engine. Complete thermo-mechanical fatigue

analysis includes both stress–strain and life predictions. The key elements

in the analysis include the following (Fig. 2.5):

∑ dynamic thermal loading

∑ dynamic mechanical loading

∑ transient component temperature distribution

∑ material constitutive law (behavior) under both low and high tempera-

tures

∑ stress and strain

∑ fatigue criteria and damage indicator

∑ component lifetime prediction

∑ statistical probabilistic prediction to account for the variations in the

population.

The temperature eld calculation is dependent on the thermal history and

thermal inertia of the engine as well as the gas temperature and mass ow

rate during the transient cycles. The effects of three-dimensional stresses

and anisothermal cycle may be important in damage indicator calculation

for detailed component-level design analysis.

A comprehensive review of engine thermo-mechanical fatigue was provided

by Ogarevic et al. (2001). The simulation methodologies of thermo-mechanical

fatigue life prediction were presented by Swanger et al. (1986), Lowe and

Morel (1992), Zhuang and Swansson (1998), and Ahdad and Soare (2002).

A discussion of diesel engine cumulative fatigue damage was provided by

Junior et al. (2005). Deformation and stress analysis was reviewed by Fessler

(1984).

Thermal load/Heat transfer

(cycle simulation, or CFD+FEA)

Metal temperature distribution

(cycle simulation, or CFD+FEA)

Stress and strain analysis

(structural analysis)

Damage parameter model

Fatigue life prediction

Design

Material properties

model

Mechanical loading

(cycle simulation)

2.5 Thermo-mechanical fatigue analysis process.

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 139 5/5/11 11:44:50 AM

140 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

HCF

High cycle fatigue is a type of fatigue caused by small elastic strains under

a high number of load cycles before failure occurs. The stress comes from a

combination of mean and alternating stresses. The mean stress is caused by

the residual stress, the assembly load, or the strongly non-uniform temperature

distribution. The alternating stress is a mechanical or thermal stress at any

frequency. A typical loading parameter in engine HCF is the cyclic cylinder

pressure load or component inertia load.

HCF requires a high number of loading cycles to reach fatigue failure

mainly due to elastic deformation. It has lower stresses than LCF, and the

stresses are also lower than the yield strength of the material. HCF usually

does not have macroscopic plastic deformation as large as that in LCF. The

dominant strain in HCF is mainly elastic. In contrast, the dominant strain in

LCF is plastic. Typical HCF examples are the cracks at the tangential intake

ports connected to the ame deck on the water side of the cylinder head, the

valve seat area, the piston, the crankshaft, and the connecting rod.

Because HCF is governed by elastic deformation, stress is usually a more

convenient parameter than strain to be used as the failure criterion. The HCF

life of the component is usually characterized by a stress–life curve (i.e., the

s–N

f

curve, Fig. 2.3b), where the magnitude of a cyclic stress is plotted versus

the logarithmic scale of the number of cycles to failure. For constant cyclic

loading, an empirical formula of the HCF s–N

f

curve is usually expressed

as

sN

C

C

sN

C

sN

f

sN

1

sN

=

2

2.5

where C

1

and C

2

are constants, s is the maximum stress in the load cycle, N

f

is

the HCF life in terms of the number of cycles to failure. Higher stress results

in a shorter life. Higher material strength can improve the HCF life.

LCF

LCF is a type of fatigue caused by large plastic strains under a low number

of load cycles before failure occurs. High stresses greater than the material

yield strength are developed in LCF due to mechanical or thermal loading.

For instance, high tensile stresses are developed after the hot compressed

area has cooled down during one loading cycle. The stresses may exceed the

yield strength and cause large plastic deformation. Like other failures the

crack due to LCF is usually initiated in the small areas having stress–strain

concentration. The failure criterion of LCF can be a macroscopic crack with

certain length or depth or a complete fracture of the component. Typical

examples of LCF failure are the cracks at the inter-valve bridge area in the

cylinder head and in the exhaust manifold after thermal cycles.

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 140 5/5/11 11:44:50 AM

141Durability and reliability in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

The lifetime of the component in LCF can be predicted by either plastic

strain amplitude or stress amplitude, with the former being more appropriate

and commonly used. In fact, both maximum tensile stress and the strain

amplitude are useful in LCF life prediction. In general, larger plastic strains

cause a shorter life. Better material ductility can improve the LCF life. Higher

material strength may actually reduce the component life if it is subject to

LCF failure since higher material strength usually reduces ductility.

Under a single type of cyclic loading (i.e., the plastic strain range remains

constant in every cycle of the loading) the plastic strain deformation is

usually predicted by the Manson–Cof n relation developed in the 1950s.

The formula characterizes the relationship between the plastic strain range

and LCF life as follows:

D

e

p

f

C

NC

f

NC

f

C

NC

C

NC

–

NC

4

3

NC

3

NC

NC =NC

i.e.,

D

e

p

f

C

CN

=

4

CN

4

CN

3

2.6

where De

p

is the plastic strain range, N

f

is the number of load cycles to

reach fatigue failure. Note that 2N

f

is the number of reversals to failure in

the stress–strain hysteresis loop. C

3

and C

4

are empirical material constants.

C

3

is known as the fatigue ductility exponent, usually ranging from –0.5

to –0.7. Higher temperature gives a more negative value of C

3

. C

4

is an

empirical constant known as the fatigue ductility coef cient, which is closely

related to the fracture ductility of the material. It is observed from equation

2.6 that a larger plastic strain range leads to a lower number of cycles of

the fatigue life.

A more general relationship was later proposed by Mason by using the

total strain, including both elastic and plastic strains, as the indicator of LCF

failure:

DD

D

ee

DD

ee

DD

e

tota

ee

tota

ee

DD

ee

DD

tota

DD

ee

DD

lp

ee

lp

ee

DD

ee

DD

lp

DD

ee

DD

e

f

C

f

C

CN

CN

DD

ee

DD =DD

ee

DD

DD

ee

DD

lp

DD

ee

DD =DD

ee

DD

lp

DD

ee

DD

lp

lp

ee

lp

ee

ee

lp

ee

DD

ee

DD

lp

DD

ee

DD DD

ee

DD

lp

DD

ee

DD

+

=

CN CN

+

46

f

46

f

CN

46

CN

CN

46

CN

46

f

f

46

f

f

CN CN

46

CN CN

+

46

+

35

C

35

C

CN

35

CN

+

35

+

2.7

where De

e

is the elastic strain range which is equal to the elastic stress

range divided by the Young’s modulus, De

p

is the plastic strain range,

C

6

is a coef cient related to the fatigue strength, C

3

and C

5

are material

constants. Equation 2.7 can be used to construct the strain–life diagram for

the component on a logarithmic scale (Fig. 2.3c).

The LCF in diesel engines is usually caused by large thermal stresses at

high component temperatures which are higher than the creep temperature.

The creep temperature is usually equal to 30–50% of the melting temperature

of the metal in Kelvin. Many factors such as creep, relaxation, oxidation,

and material degradation start to play important roles at high temperatures.

At low temperatures the fatigue mechanism is predominant, while at high

temperatures creep may become more important. The life of high temperature

LCF is usually signi cantly lower than the life at lower temperatures (Fig.

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 141 5/5/11 11:44:51 AM

142 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

2.3d). Ductility is a major factor to determine the LCF life. The material

ductility is affected by temperature. Moreover, if the frequency of the loading

cycle becomes slower, high temperature LCF life will reduce since creep

and oxidation play more prominent roles at lower cycle frequencies. When

the creep effect is considered, equation 2.6 is modi ed as below, and such

a modi cation has been widely used to estimate the LCF life:

D

e

pc

f

ql

C

C

CN

f

ql

f

ql

=

(

CN (CN

)

4

(

4

(

CN (CN

4

CN (CN

–1

7

3

2.8

where De

pc

is the inelastic strain range including the plastic strain range

and the creep strain range, C

7

is a material constant, f

ql

is the cyclic loading

frequency which accounts for the time-related effects of creep (e.g., the creep

hold time) and relaxation, and so on. The elastic strain term in equation 2.7

can be modi ed similarly.

Barlas et al. (2006) provided an analysis to calculate the number of cycles

to failure due to pure creep as an integral over a time period of t

1

–t

2

for the

cylinder head:

1

=

1

+ 1

d

d

89

+ 1

89

+ 1

1

89

1

89

2

d

2

d

10

NC

=

NC

=

s

d

s

d

t

f

NC

f

NC

t

89

t

89

t

C

Ú

d

Ú

d

89

Ú

89

t

Ú

t

89

t

89

Ú

89

t

89

Ê

d

Ê

d

Ë

d

Ë

d

89

Ë

89

d

Á

d

Ê

Á

Ê

d

Ê

d

Á

d

Ê

d

Ë

Á

Ë

d

Ë

d

Á

d

Ë

d

89

Ë

89

Á

89

Ë

89

ˆ

d

ˆ

d

¯

d

¯

d

d

˜

d

ˆ

˜

ˆ

d

ˆ

d

˜

d

ˆ

d

¯

˜

¯

d

¯

d

˜

d

¯

d

C

d

C

d

89

C

89

2.9

where C

8

, C

9

and C

10

are material coef cients for pure creep, and s is an

equivalent stress as a linear combination of the Von Mises stress, the principal

maximum stress and the trace of the stress tensor.

Strictly speaking, the classical LCF laws (e.g., the Manson–Cof n

relation) based on the isothermal and uni-axial conditions are not valid for

the anisothermal and multi-axial problems in reality. Therefore, the available

prevailing analysis method is more or less a simpli ed approximation for

the real world durability problems encountered in engines. Predicting the

LCF life in the anisothermal and multi-axial conditions is very challenging,

especially for the concept-level structural/life analysis in engine system design.

Lederer et al. (2000) provided an in-depth discussion on the limitations of

the classical CLF theories for fatigue life prediction. Lederer et al. (2000)

also showed that, using a reasonably simple anisothermal LCF criterion,

their simulation produced good agreement between the predicted and the

tested critical zones of failure.

Thermal shock

Thermal shock refers to the process that the component experiences suddenly

changed thermal stresses and strains of large magnitude when the heat

ux and component temperature gradient change abruptly. Thermal shock

produces cracks as a result of rapid component temperature change. The

stresses generated in thermal shock are much greater than those in normal

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 142 5/5/11 11:44:52 AM

143Durability and reliability in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

loading cycles, and even greater than the ultimate strength of the material.

Thermal shock can be regarded as a severe type of LCF although it has its

unique characteristics. The criterion used to analyze thermal shock failures

can be strain or stress, with strain being more appropriate.

Thermal shock can make the material lose ductility and shorten the normal

LCF life and the thermal fatigue life of the component accordingly. It may

also cause brittle fracture which has a much shorter life than the normal

LCF life. The materials having low thermal conductivity and high thermal

expansion coefcient are vulnerable to thermal shock. Thermal shock can be

prevented by reducing the thermal gradient through changing the temperature

more slowly, or by improving the robustness of a material against thermal

shock through increasing a ‘thermal shock parameter’. The parameter is

an indicator of the capability to resist thermal shock, and is proportional

to the thermal conductivity and the maximum tension that the material can

resist, and inversely proportional to the thermal expansion coefcient and

the Young’s modulus.

2.9 Diesel engine thermo-mechanical failures

2.9.1 Cylinder head durability

Failure mechanisms of cylinder head

Cylinder head fatigue and cracking are among the most important issues

in engine durability development. Cylinder head durability is limited by

thermo-mechanical fatigue. Controlling the maximum metal temperature

and temperature gradient in the cylinder head is the key to solving thermal

fatigue problems. The cylinder head has two major failure modes: the HCF

crack due to cylinder pressure loading (high stress) at the coolant side, and

the LCF crack caused by severe thermal loading (high plastic strain) at the

gas side. Kim et al. (2005) pointed out that HSDI diesel cylinder head tends

to have more cracks in the water jacket area due to HCF than the cracks on

the gas-side re deck due to LCF. Maassen (2001) summarized the failure

modes for the diesel cylinder head.

There are four types of load in the cylinder head as follows:

∑ Preload stresses coming from the manufacturing process, such as the

residual stresses due to molding, heat treatment (e.g., quenching) and

machining processes.

∑ Assembly loads such as bolting load and press-ts. The residual stresses

and the assembly loads affect the value of the mean stress hence the

fatigue life and cylinder head durability.

∑ Mechanical operating load due to cylinder gas pressure.

∑ Thermal load caused by high in-cylinder gas temperatures and large

variation of temperatures during operating duty cycles.

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 143 5/5/11 11:44:52 AM

144 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

HCF in cylinder head

Because the diesel engine operates under high peak cylinder pressures, HCF

cracks occur frequently, especially in the water jacket area in the cylinder

head. High tensile residual stresses generated from the heat treatment

processes were found to cause cracks at the foot of the long intake port

with the lowest safety factor (Kim et al., 2005). They also found that the

bolting load of the cylinder head induces bending deformation and tensile

stresses at the crack location. The ring gas pressure load and thermal load

increase the tensile stresses.

There could be a large variation in stress levels from cylinder to cylinder due

to inhomogeneous component temperature distributions. Design solutions for

the cracking problem include increasing the bending stiffness at the cracking

location in order to reduce the amount of bending, and reducing the tensile

residual stresses with better heat treatment process during manufacturing.

Design solutions for cylinder head HCF problems were elaborated by Hamm

et al. (2008) with the use of minimum safety factors as design evaluation

criteria to compare different designs.

LCF in cylinder head

The LCF cracks in the cylinder head occur mainly on the gas-side re

deck at the inter-valve bridge area between the valves, the area between

the injector hole and the exhaust valve seat, and the area between the glow

plug bore and the exhaust valve seat, especially in the inter-valve bridge

area between the intake and exhaust valves. The cracks are caused mainly

by large thermal loading, temperature gradients, and thermal stresses in the

relatively slow varying thermal cycles and the decreased material strength

at elevated temperatures. Compressive stresses are generated in the cylinder

head under high temperatures due to constrained thermal expansion. When

the cylinder head temperature reduces at the low-load conditions, the material

contracts. This results in high tensile stresses. Large temperature variations

combined with the effects of creep and material thermal aging can make

the local tensile stresses exceed the yield strength of the material under the

hot condition to produce plastic strain amplitude. After a number of such

hot–cold thermal cycles, cracking is initiated and propagates as the damage

cumulates. A typical example of such a thermal fatigue cycle is the engine

start–stop.

Although the metal temperature in the bridge area between the intake and

exhaust valves is colder than that in the bridge area between the two exhaust

valves, the intake–exhaust bridge is usually weaker in LCF due to a larger

temperature gradient (Zieher et al., 2005). The LCF thermal fatigue in that

area imposes a constraint for engine system design in terms of thermal loading

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 144 5/5/11 11:44:52 AM

145Durability and reliability in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

encountered by the engine during thermal cycles. One way to alleviate the

thermal LCF fatigue is to prevent the metal temperature from increasing

to a point where the elastic limit (yield strength) of the material starts to

decrease (Gale, 1990).

Thermo-mechanical fatigue life prediction of cylinder head

Diesel engine cylinder head design was reviewed by Gale (1990). Design

solutions to the thermo-mechanical fatigue problems of diesel cylinder

heads were provided by Kim et al. (2005) and Hamm et al. (2008). Maassen

(2001) provided a detailed discussion on residual stresses, HCF and LCF for

cylinder heads. The structural modeling of thermo-mechanical fatigue failures

of diesel cylinder heads was investigated by Koch et al. (1999), Lee et al.

(1999), Maassen (2001), Su et al. (2002), Zieher et al. (2005), and Barlas

et al. (2006). Su et al. (2002) analyzed the cast aluminum cylinder head,

while Zieher et al. (2005) analyzed the cast iron cylinder head (gray cast

iron, compacted graphite iron, ductile iron). Koch et al. (1999) developed

a simulation tool to calculate the strains and stresses as a function of time

for a dened engine operating cycle. Cyclic thermal load of temperature

variation is applied to the FEA models of the cylinder head.

The thermo-mechanical damage of the diesel cylinder heads that are made

of cast aluminum usually includes the accumulation of fatigue, oxidation, and

creep (Su et al., 2002). The damage of the cylinder heads that are made of

gray cast iron includes one more mechanism – embrittlement. Zieher et al.

(2005) described a constitutive model, a damage model and a life prediction

model for the cast iron cylinder heads by considering three mechanisms:

fatigue, creep, and embrittlement. They pointed out that for gray cast iron,

brittle damage plays an important role in thermal cycles with large thermal

strains.

Su et al. (2002) introduced a unied visco-plastic constitutive model

for the material behavior, and extended the uni-axial thermo-mechanical

fatigue life analysis to a three-dimensional analysis of stress and fatigue

damage. Barlas et al. (2006) accounted for the effect of material aging in

their constitutive model, which is important for diesel engine cylinder head

durability analysis.

2.9.2 Exhaust manifold durability

Exhaust manifold loading and impact on engine performance

The exhaust manifold consists of the inlet ange, exhaust pipes (also called

runners) and the outlet ange with gaskets and bolts. There are four types

of loads acting on the exhaust manifold:

Diesel-Xin-02.indd 145 5/5/11 11:44:52 AM