Whetten David A., Cameron Kim S. Developing management skills

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 347

generally informal, discussions with their subordinates.

One approach used by some managers is to discuss with

subordinates recent significant changes in the roles or

work assignments of common acquaintances, possibly

involving a promotion, a change of work assignment, or a

transfer to a new location or work unit. Subordinates’

responses to the consequences of these changes, includ-

ing level of pay, type of pay (e.g., sales commissions

vs. salary), travel expectations, responsibilities for coordi-

nating the work of others, level of pressure to produce,

capitalizing on old skills vs. learning new ones, an

individual vs. team-oriented work environment, opportu-

nities for promotion, and so forth, often provide insights

into their own personal preferences. When engaging in

discussions such as these, keep in mind information

regarding preferred trade-offs is particularly useful. In the

abstract, everyone values everything. In reality, we have

to make choices and those choices reflect our underlying

needs and values. Thus, it is particularly instructive to see

how someone responds to the prospect that a colleague’s

new job provides opportunities for more pay, but at the

expense of being away from home three nights a week.

Or, the opportunity to be involved with the design of a

new product line also means longer hours at work, higher

levels of personal stress, and the possibility that the failure

to meet high expectations may reflect negatively on the

team members.

The data reported in Table 6.8 is also relevant for

individuals in a position to shape the pay and benefits

package for an entire organization. Scanning these

results, it is easy to pick out differences between

the ratings of blue-collar vs. white-collar, unskilled

and skilled, lower and higher level employees.

Recognizing the wide diversity in outcome preferences

within the employee ranks of most large businesses,

many firms, ranging from investment banks, like

Morgan Stanley, to manufacturing firms, like American

Can, have experimented with “cafeteria-style” incen-

tive systems (Abbott, 1997; Lawler, 1987). This

approach takes much of the guesswork out of linking

an individual’s organizational membership and work

performance with personally salient outcomes, by

allowing employees some say in the matching process.

Using this approach, employees receive a certain num-

ber of work credits based on performance, seniority, or

task difficulty, and they are allowed to trade those in

for a variety of benefits, including upgraded insurance

packages, financial planning services, disability income

plans, extended vacation benefits, tuition reimburse-

ment for educational programs, and so forth.

Table 6.8 What Workers Want, Ranked by Subgroups*

ALL EMPLOYEES

MEN

WOMEN

UNDER 30

31–40

41–50

O

VER 50

U

NDER $25,000

$25,001–$40,000

$40,001–$50,000

O

VER $50,000

B

LUE-COLLAR

UNSKILLED

BLUE-COLLAR

SKILLED

WHITE-COLLAR

UNSKILLED

WHITE-COLLAR

SKILLED

LOWER

NONSUPERVISORY

MIDDLE

NONSUPERVISORY

HIGHER

NONSUPERVISORY

Interesting work 1 1 2 4 2 3 1 5 2 1 1 2 1 1 2 3 1 1

Full appreciation of

work done 2 2 1 5 3 2 2 4 3 3 2 1 6 3 1 4 2 2

Feeling of being in on

things 3 3 3 6 4 1 3 6 1 2 4 5 2 5 4 5 3 3

Job security 4 5 4 2 1 4 7 2 4 4 3 4 3 7 5 2 4 6

Good wages 5 4 5 1 5 5 8 1 5 6 8 3 4 6 6 1 6 8

Promotion and growth

in organization 6 6 6 3 6 8 9 3 6 5 7 6 5 4 3 6 5 5

Good working conditions 7 7 10 7 7 7 4 8 7 7 6 9 7 2 7 7 7 4

Personal loyalty to

employees 8 8 8 9 9 6 5 7 8 8 5 8 9 9 8 8 8 7

Tactful discipline 9 9 9 8 10 9 10 10 9 9 10 7 10 10 9 9 9 10

Sympathetic help with

personal problems 10 10 7 10 8 10 6 9 10 10 9 10 8 8 10 10 10 9

*Ranked from 1 (highest) to 10 (lowest).

S

OURCE: Courtesy of George Mason University. Results are from a study of 1,000 employees conducted in 1995.

348 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

BE FAIR AND EQUITABLE

Once appropriate rewards have been determined for

each employee, managers must then consider how to

distribute those rewards (Cropanzano & Folger, 1996).

This brings us to concerns about equity. Any positive

benefits of salient rewards will be negated if workers

feel they are not receiving their fair share. The relevant

diagnostic question here is, “Do subordinates feel that

work-related benefits are distributed fairly?” (As in the

previous section, we will focus here only on rewards.

However, the same principles also apply to the equi-

table use of discipline.)

Equity refers to workers’ perceptions of the fair-

ness of rewards. Evaluations of equity are based on a

social comparison process in which workers individu-

ally compare what they are getting out of the work

relationship (outcomes) to what they are putting into

the work relationship (inputs). Outcomes include such

items as pay, fringe benefits, increased responsibility,

and prestige, while inputs may include hours worked

and work quality, as well as education and experience.

The ratio of outcomes to inputs is then compared to

corresponding ratios of other individuals, judged to be

an appropriate comparison group. The outcome of this

comparison is the basis for beliefs about fairness.

If workers experience feelings of inequity, they

will behaviorally or cognitively adjust their own or

fellow workers’ inputs and/or outputs. In some cases,

this may lead to a decrease in motivation and perfor-

mance. For example, if employees believe they are

underpaid, they have a number of options. Cognitively,

they may rationalize they really are not working as

hard as they thought they were; thus, they reduce the

perceived value of their own inputs. Alternatively, they

might convince themselves coworkers are actually

working harder than they thought they were. Behav-

iorally, workers can request a pay raise (increase

their outcomes), or they can decrease their inputs by

leaving a few minutes early each day, decreasing their

effort, deciding not to complete an optional training

program, or finding excuses not to accept difficult

assignments.

The significance of this aspect of motivation

underscores the need for managers to closely monitor

subordinates’ perceptions of equity (Janssen, 2001). In

some cases, these conversations may uncover faulty

comparison processes. For example, employees might

misunderstand the value placed on various inputs,

such as experience versus expertise or quantity versus

quality; or they might have unrealistic views of their

own or others’ performance. It has been noted most

people believe their leadership skills are better than

those of most of the population.

However, just as often these discussions uncover

real inequities. For example, the hourly rate of a

worker may not be keeping up with recent skill

upgrades or increased job responsibilities. The act of

identifying and correcting legitimate inequities gener-

ates enormous commitment and loyalty. For example,

a manager in the computer industry felt he had been

unfairly passed over for promotion by a rival. Utilizing

the company’s open-door policy, he took his case to a

higher level in the firm. After a thorough investigation,

the decision was reversed and the rival reprimanded.

The individual’s response was, “After they went to bat

for me, I could never leave the company.”

The important thing to keep in mind about equity

and fairness is we are dealing with perceptions.

Consequently, whether they are accurate or dis-

torted, legitimate or ill-founded, they are both accurate

and legitimate in the mind of the perceiver until proven

otherwise. A basic principle of social psychology states:

“That which is perceived as being real is real in its

consequences.” Therefore, effective managers should

constantly perform “reality checks” on their subordi-

nates’ perceptions of equity, using questions such as:

“What criteria for promotions, pay raises, and so on do

you feel management should be placing more/less

emphasis on?” “Relative to others similar to you in this

organization, do you feel your job assignments, promo-

tions, and so on are appropriate?” “Why do you think

Alice was recently promoted over Jack?”

PROVIDE TIMELY REWARDS

AND ACCURATE FEEDBACK

Up to this point, we have emphasized employees need

to understand and accept performance standards; they

should feel that management is working hard to help

them reach their performance goals; they should feel

that available internal and external rewards are

personally attractive; they should believe rewards and

reprimands are distributed fairly; and they should feel

these outcomes are administered primarily on the basis

of performance.

All these elements are necessary for an effective

motivational program, but they are not sufficient. As

we noted earlier, a common mistake is to assume all

rewards are reinforcers. In fact, the reinforcing potential

of a “reward” depends on its being linked in the mind of

the reward recipient to the specific behaviors the

reward giver desires to strengthen. (“When I did behav-

ior X, I received outcome Y. And, because I value Y, I am

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 349

going to repeat X.”) The ability of reward recipients to

make this reinforcing (X behavior–Y outcome) mental

connection is related to two specific aspects of how the

reward is administered: (1) the length of time between

the occurrence of the desirable behavior and the receipt

of the reward, and (2) the specificity of the explanation

for the reward. These are the two final components of

our motivational program. Hence, the sixth and final

diagnostic question contains two parts. The first is, “Are

we getting the most out of our rewards by administering

them on a timely basis as part of the feedback process?”

As a general rule, the longer the delay in the admin-

istration of rewards the less reinforcement value they

have. Even if the recipient greatly values the recognition

and the reward giver clearly identifies the behaviors

being rewarded, unless the reward is received soon after

the behavior has been exhibited (or the goal accom-

plished), the intended reinforcement value of the

reward is diminished.

Ironically, in a worst-case situation, the mistiming

of a reward may actually reinforce undesirable behav-

iors. Giving a long overdue, fully warranted raise to a

subordinate during an interview in which she or he is

complaining about the unfairness of the reward system

may reinforce complaining rather than good work per-

formance. Moreover, failure to give a reward when a

desired behavior occurs will make it even more difficult

to sustain that behavior in the future. If the owners of

a new business have delayed the implementation of a

promise to grant stock options for the core start-up cadre

as compensation for their low wages and 70- to 80-hour

workweeks, the workers’ willingness to sustain such a

pace on promises and dreams alone may begin to wane.

The importance of timing becomes obvious when

one considers all the research findings supporting the

value of operant conditioning as a motivational system

assume outcomes immediately follow behaviors.

Imagine how little we would know about behavior-

shaping processes if, in the experiments with birds and

rats described in psychology textbooks, the food pellets

were dropped into the cage several minutes after the

desired behavior occurred.

Today’s managers have a number of technological

tools that can be used to speed up feedback. Hatim

Tyabji, while serving as CEO of Verifone, used e-mail to

reinforce important contributions. “We recently had a

major win in a market where we hadn’t been hav-

ing much success. Against all odds, we went after a

big customer and won. When I got word that we

had won—and I’m so enmeshed in the organization

that people just ignore the hierarchy and e-mail me that

kind of news—my first reaction, apart from pure joy,

was: Why did we win? My next question was: Who

are the key people who made the difference? Then I

immediately sent out a message of congratulations. The

e-mails and phone calls I got back were enough to

make my eyes moist. That to me is what makes us tick”

(Adria, 2000; Nelson, 2000; Taylor, 1995).

Unfortunately, although timing is a critical contrib-

utor to the reinforcement potential of a reward, it is fre-

quently ignored in everyday management practice. The

formal administrative apparatus of many organizations

often delays for months the feedback on the conse-

quences of employee performance. It is customary prac-

tice to restrict in-depth discussions of job performance to

formally designated appraisal interviews, which gener-

ally take place every six or twelve months. (“I’ll have to

review this matter officially later, so why do it twice?”)

The problem with this common practice is the resulting

delay between performance and outcomes dilutes the

effectiveness of any rewards or discipline dispensed as a

result of the evaluation process.

In contrast, effective managers understand the

importance of immediate, spontaneous rewards. They

use the formal performance evaluation process to discuss

long-term trends in performance, solve problems inhibit-

ing performance, and set performance goals. But they

don’t expect these infrequent general discussions to sig-

nificantly alter an employee’s motivation. For this, they

rely on brief, frequent, highly visible performance feed-

back. At least once a week they seek some opportunity

to praise desirable work habits among their subordinates.

Peters and Waterman, in their classic book In

Search of Excellence (1988), stress the importance of

immediacy by relating the following amusing anecdote:

At Foxboro, a technical advance was desper-

ately needed for survival in the company’s

early days. Late one evening, a scientist

rushed into the president’s office with a work-

ing prototype. Dumbfounded at the elegance

of the solution and bemused about how to

reward it, the president bent forward in his

chair, rummaged through most of the drawers

in his desk, found something, leaned over the

desk to the scientist, and said, “Here!” In his

hand was a banana, the only reward he could

immediately put his hands on. From that

point on, the small “gold banana” pin has

been the highest accolade for scientific

achievement at Foxboro. (pp. 70–71)

The implication for effective management is clear:

effective rewards are spontaneous rewards. Reward

350 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

programs that become highly routinized, especially

those linked to formal performance appraisal systems,

lose their immediacy.

There is a second critical aspect of reinforcement

timing: the consistency of reward administration.

Administering a reward every time a behavior occurs

is called continuous reinforcement. Administering

rewards on an intermittent basis (the same reward is

always used but is not given every time it is warranted)

is referred to as partial, or intermittent, reinforcement.

Neither approach is clearly superior; both approaches

have trade-offs. Continuous reinforcement represents

the fastest way to establish new behavior. For example,

if a boss consistently praises a subordinate for writing

reports using the manager’s preferred format, the sub-

ordinate will readily adopt that style in order to receive

more and more contingent rewards. However, if the

boss suddenly takes an extended leave of absence, the

learned behavior will be highly vulnerable to extinc-

tion because the reinforcement pattern is broken. In

contrast, while partial reinforcement results in very

slow learning, it is very resistant to extinction. The

persistence associated with gambling behavior illus-

trates the addictive nature of a partial reinforcement

schedule. Not knowing when the next payoff may

come preserves the myth that the jackpot is only one

more try away.

This information about reinforcement timing

derived from experimental research has important

implications for effective management. First, it is impor-

tant to realize continuous reinforcement systems are

very rare in organizations unless they are mechanically

built into the job, as in the case of the piece-rate

pay plan. Seldom are individuals rewarded every time

they make a good presentation or effectively handle

a customer’s complaint. When we recognize most

non-assembly-line work in an organization is typically

governed by a partial reinforcement schedule, we gain

new insights into some of the more frustrating aspects of

a manager’s role. For example, it helps explain why new

employees seem to take forever to catch on to how the

boss wants things done. It also suggests why it is so dif-

ficult to extinguish outdated behaviors, particularly in

older employees.

Second, given how difficult it is for one manager

to reinforce consistently the desired behaviors in

a new employee (or an employee who is going

through a reprimand, redirect, reward cycle), it is gen-

erally a good idea to use a team effort. By sharing your

developmental objectives with other individuals who

interact with the target employee, you increase the

likelihood of the desired behaviors being reinforced

during the critical early stages of improvement. For

example, if a division head is trying to encourage a

new member of her staff to become more assertive,

she might encourage other staff members to respond

positively to the newcomer’s halting efforts in meet-

ings or private conversations.

This brings us to the second half of the sixth

diagnostic question, related to the accuracy of feed-

back, “Do subordinates know where they stand in

terms of current performance and long-term opportuni-

ties?” In addition to the timing of feedback, the content

of feedback significantly affects its reinforcement poten-

tial. As a rule of thumb, to increase the motivational

potential of performance feedback, be very specific—

including examples whenever possible. Keep in mind

feedback, whether positive or negative, is itself an out-

come. The main purpose for giving people feedback on

their performance is to reinforce productive behaviors

and extinguish counterproductive behaviors. But this

can only occur if the feedback focuses on specific behav-

iors. To illustrate this point, compare the reinforcement

value of the following, equally positive, messages: “You

are a great member of this team—we couldn’t get along

without you.” “You are a great member of this team. In

particular, you are willing to do whatever is required to

meet a deadline.”

It is especially important managers provide accu-

rate and honest feedback when a person’s performance

is marginal or substandard. There are many reasons

why managers are reluctant to “tell it like it is” when

dealing with poor performers. It is unpleasant to

deliver bad news of any kind. It is especially painful

to give negative feedback regarding a person’s perfor-

mance. Therefore, it is easy to justify sugarcoating neg-

ative information, especially when it is unexpected, on

the basis that you are doing the recipient a favor. In

practice, it is rarely the case that a poor performer is

better off not receiving detailed, honest, accurate feed-

back. If the feedback is very general, or if it contains

mixed signals, improvement is frustratingly difficult.

And if a person truly is not well suited for a particular

job, then no one benefits from delaying a shift in

responsibilities or encouragement to seek other work

opportunities.

When managers are reluctant to share unflatter-

ing or unhopeful feedback, it is often because they are

unwilling to spend sufficient time with individuals

receiving negative feedback to help them thoroughly

understand their shortcomings, put them in perspec-

tive, consider options, and explore possible remedies.

It is sometimes easier to pass on an employee with a

poor performance record or unrealistic expectations

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 351

to the next supervisor than it is to confront the

problem directly, provide honest and constructive

feedback, and help the individual respond appropri-

ately. Therefore, many individuals feel that supportive

communication of negative performance information

is the management skill which is most difficult to

master—and therefore the one most highly prized. If

you are particularly interested in polishing this skill,

we recommend you review the specific techniques

described under the heading “Use Rewards and

Discipline Appropriately.”

Summary

Our discussion of enhancing work performance has

focused on specific analytical and behavioral manage-

ment skills. We first introduced the fundamental

distinction between ability and motivation. Then we

discussed several diagnostic questions for determining

whether inadequate performance was due to insuffi-

cient ability. A five-step process for handling ability

problems (resupply, retrain, refit, reassign, and release)

was outlined. We introduced the topic of motivation

by stressing the need for placing equal emphasis on

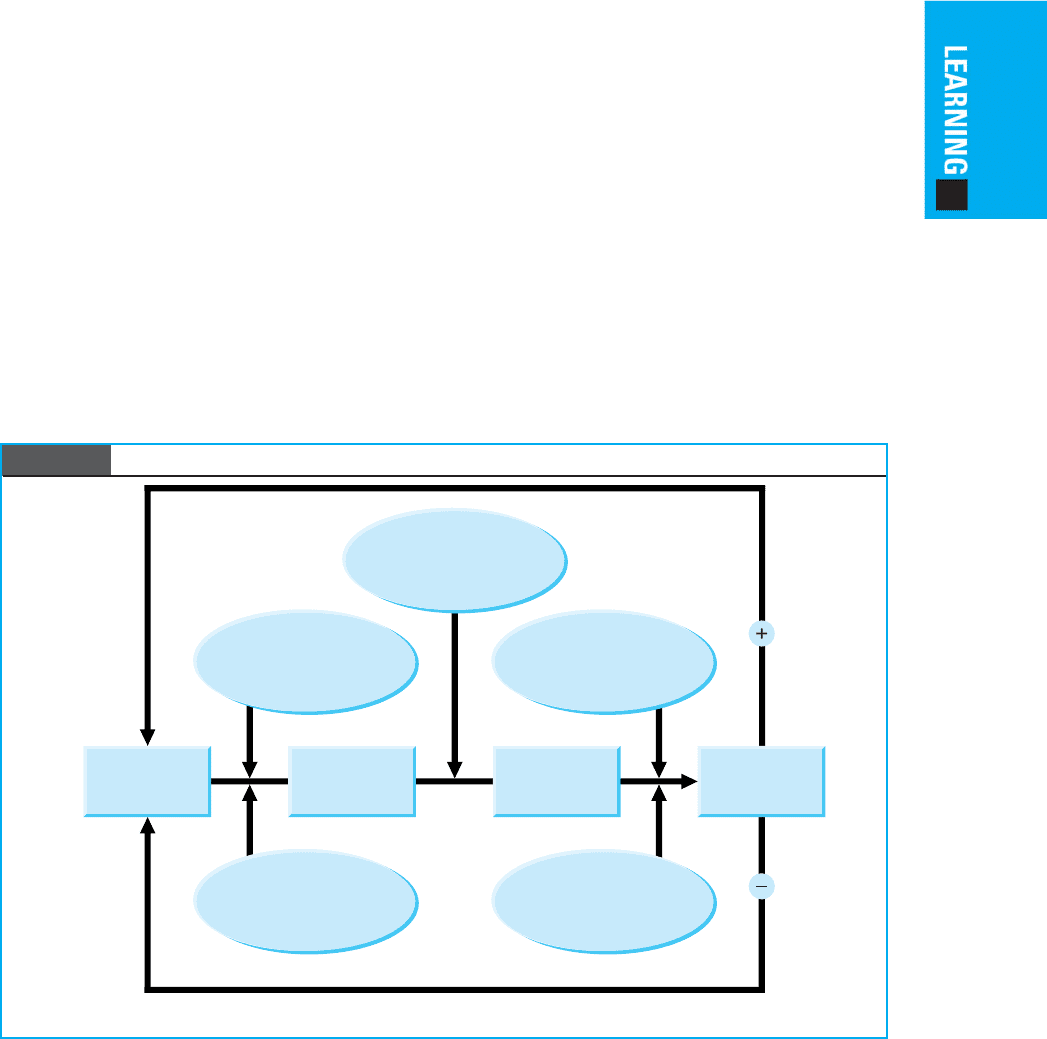

Figure 6.5 Integrative Model of Motivation Enhancement

concerns for satisfaction and performance. The

remainder of this chapter focused on the second skill

by presenting six elements of an integrative approach

to motivation.

The summary model shown in Figure 6.5 (and its

“diagnostic” version discussed in the Skill Practice

section as Figure 6.7) highlights our discussion of an

expanded version of the basic “four factors” model of

motivation. The resulting comprehensive model

underscores the necessary role of, as well as the inter-

dependence among, the various components. Skilled

managers incorporate all components of this model into

their motivational efforts rather than concentrating

only on a favorite subset. There are no shortcuts to

effective management. All elements of the motivation

process must be included in a total, integrated program

for improving performance and satisfaction.

The fact the flowchart begins with motivation is

important, because it makes explicit our assumption

individuals are initially motivated to work hard and do

a good job. Recall motivation is manifested as work

effort and effort consists of desire and commitment.

This means that motivated employees have the desire

to initiate a task and the commitment to do their best.

Note: 1–6: Key to six diagnostic questions in Table 6.2.

MOTIVATION

(Effort)

PERFORMANCE

OUTCOMES

(Extrinsic and

Intrinsic)

SATISFACTION

3. REINFORCEMENT

• Discipline

• Rewards

1. GOALS/EXPECTATIONS

• Accepted

• Challenging and specific

• Feedback

4. EQUITY

• Social comparisons

• Personal expectations

5. SALIENCE

• Personal needs

6. TIMELINESS

2. ABILITY

• Aptitude

• Training

• Resources

1–6: Key to six diagnostic questions in Table 2.

352 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

Whether their motivation is sustained over time

depends on the remaining elements of the model,

which are actually amplifications of the Motivation →

Performance link, the Performance → Outcomes link,

and the Outcomes → Satisfaction link. These crucial

links in the motivational process can best be summa-

rized as questions pondered by individuals asked to

work harder, change their work routine, or strive for a

higher level of quality: First, “If I put forth more effort,

am I likely to be able to perform up to perfor-

mance expectations?” Second, “Will my level of perfor-

mance matter in this organization?” Third, “Will the

experience of being a high performer likely be person-

ally rewarding?”

Beginning on the left side of the model, we see

that the combination of goals and ability determines

the extent to which effort is successfully transformed

into performance. In the path-goal theory of leader-

ship, the importance of fitting the right job to the right

person and providing necessary resources and training

is emphasized. These factors must be combined with

effective goal setting (understanding and accepting

moderately difficult goals) if increased effort is to result

in increased performance.

The next section of the model focuses on reinforc-

ing good performance, in terms of both increasing the

frequency of performance-enhancing behaviors and

linking outcomes to successful goal accomplishment. It

is important to keep in mind people are, in general,

motivated by both extrinsic and intrinsic outcomes. In

addition, the effective manager is adept at using the full

range of behavior-shaping tools, spanning the spectrum

from discipline to rewards. Although our discussion

focused more on rewards than discipline, when faced

with the challenge of providing constructive but

negative performance feedback, and developing an

accompanying plan for remediation, Table 6.5 provides

a useful set of guidelines.

Proceeding to the Outcomes → Satisfaction seg-

ment of the model, the importance of perceived equity

and reward salience stands out. Individuals must believe

the rewards offered are appropriate, not only for their

personal performance level but also in comparison to the

rewards achieved by “similar” others. The subjective

value that individuals attach to incentives for perfor-

mance reflects their personal relevance, or salience.

Rewards with little personal value have low motivational

potential. These subjective factors combine with the

timeliness and accuracy of feedback to determine the

overall motivational potential of rewards.

Based on their perceptions of outcomes, workers

will experience varying degrees of satisfaction or

dissatisfaction. Satisfaction creates a positive feedback

loop, increasing the individual’s motivation, as mani-

fested by increased effort. Dissatisfaction, on the other

hand, results in decreased effort and, therefore, lower

performance and rewards. If uncorrected, this pattern

may ultimately result in absenteeism or turnover.

Behavioral Guidelines

This discussion is organized around key diagnostic

models and questions that serve as the basis for

enhancing the following skills: (1) properly diagnosing

performance problems; (2) initiating actions to enhance

individuals’ abilities; and (3) strengthening the motiva-

tional aspects of the work environment.

Table 6.2 summarizes the process for properly

diagnosing the causes of poor work performance in the

form of six diagnostic questions. (A “decision tree”

version of these questions is included in the Skill

Practice section as Figure 6.7.)

The key guidelines for creating a highly motivat-

ing work environment are:

1. Clearly define an acceptable level of overall

performance or specific behavioral objective.

❏ Make sure the individual understands what

is necessary to satisfy expectations.

❏ Formulate goals and expectations collabora-

tively, if possible.

❏ Make goals as challenging and specific as

possible.

2. Help remove all obstacles to reaching perfor-

mance objectives.

❏ Make sure the individual has adequate tech-

nical information, financial resources, per-

sonnel, and political support.

❏ If a lack of ability appears to be hindering

performance, use the resupply, retrain, refit,

reassign, or release series of remedies.

❏ Gear your level of involvement as a leader

to how much help a person expects, needs,

and how much help is otherwise available.

3. Make rewards and discipline contingent on

high performance or drawing nearer to the per-

formance objective.

❏ Carefully examine the behavioral consequences

of your nonresponses. (Ignoring a behavior is

rarely interpreted as a neutral response.)

❏ Use discipline to extinguish counterproductive

behavior and rewards to reinforce productive

behaviors.

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 353

4. When discipline is required, treat it as a learning

experience for the individual.

❏ Specifically identify the problem and explain

how it should be corrected.

❏ Use the reprimand and redirect guidelines in

Table 6.5.

5. Transform acceptable into exceptional behaviors.

❏ Reward each level of improvement.

❏ Use the redirect and reward guidelines in

Table 6.5.

6. Use reinforcing rewards that appeal to the

individual.

❏ Allow flexibility in individual selection of

rewards.

❏ Provide salient external rewards as well as

satisfying and rewarding work (intrinsic

satisfaction).

❏ To maintain salience, do not overuse rewards.

7. Periodically check subordinates’ perceptions

regarding the equity of reward allocations.

❏ Correct misperceptions related to equity

comparisons.

8. Provide timely rewards and accurate feedback.

❏ Minimize the time lag between behaviors and

feedback on performance, including the

administration of rewards or reprimands.

(Spontaneous feedback shapes behavior best.)

❏ Provide specific, honest, and accurate assess-

ments of current performance and long-range

opportunities.

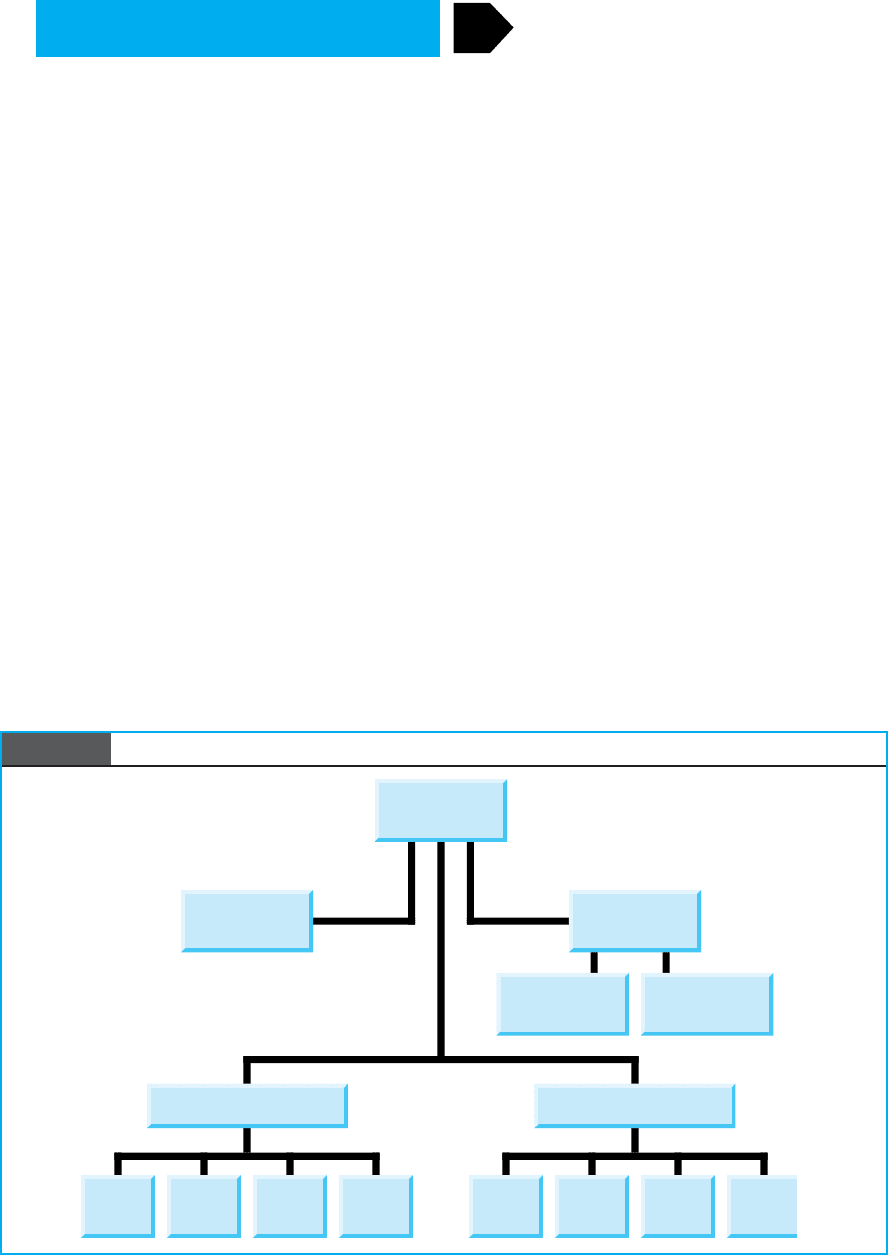

President

Vice President

Chief Financial

Officer

FacilitiesAdministration

Team

#1

Team

#2

Team

#3

Team

#4

Team

A

Team

B

Team

C

Team

D

Engineering Department Fabrication Department

354 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

SKILL

ANALYSIS

CASE INVOLVING MOTIVATION PROBLEMS

Electro Logic

Electro Logic (EL) is a small R&D firm located in a midwestern college town adjacent to a

major university. Its primary mission is to perform basic research on, and development of,

a new technology called “Very Fast, Very Accurate” (VFVA). Founded four years ago by

Steve Morgan, an electrical engineering professor and inventor of the technology, EL is

primarily funded by government contracts, although it plans to market VFVA technology

and devices to nongovernmental organizations within the year.

The government is very interested in VFVA, as it will enhance radar technology, robot-

ics, and a number of other important defense applications. EL recently received the

largest small-business contract ever awarded by the government to research and

develop this or any other technology. Phase I of the contract has just been com-

pleted, and the government has agreed to Phase II contracting as well.

The organizational chart of EL is shown in Figure 6.6. Current membership is 75,

with roughly 88 percent in engineering. The hierarchy of engineering titles and

requirements for each are listed in Table 6.9. Heads of staff are supposedly

appointed based on their knowledge of VFVA technology and their ability to manage

people. In practice, the president of EL hand-picks these people based on what some

might call arbitrary guidelines: most of the staff leaders were or are the president’s

graduate students. There is no predetermined time frame for advancement up the

hierarchy. Raises are, however, directly related to performance appraisal evaluations.

Figure 6.6 Electro Logic Organization Chart

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 355

Table 6.9 Engineering Titles and Requirements

TITLE REQUIREMENT

Member of Technical Staff BSEE, MSEE

Senior Member of Technical Staff PhD, MSEE with 2 years of industrial experience;

BSEE with 5 years of industrial experience

Research Engineer PhD with 2 years of industrial experience

BSEE or MSEE with 7 years of industrial experience

Research Scientist PhD with appropriate experience in research

Senior Research Scientist PhD with appropriate industrial and research

experience

Working directly with the engineers are the technicians. These people generally

have a high school degree, although some also have college degrees. They are trained

on the job, although some have gone through a local community college’s program on

microtechnology fabrication. The technicians perform the mundane tasks of the engi-

neering department: running tests, building circuit boards, manufacturing VFVA

chips, and so on. Most are full-time, hourly employees.

The administrative staff is composed of the staff head (with an MBA from a major

university), accountants, personnel director, graphic artists, purchasing agent, project

controller, technical writers/editors, and secretaries. Most of the people in the

administrative staff are women. All are hourly employees except the staff head, per-

sonnel director, and project controller. The graphic artists and technical writer/editor

are part-time employees.

The facilities staff is composed of the staff head and maintenance personnel. EL

is housed in three different buildings, and the primary responsibility of the facilities

staff is to ensure that the facilities of each building are in good working order.

Additionally, the facilities staff is often called upon to remodel parts of the buildings

as the staff continues to grow.

EL anticipates a major recruiting campaign to enhance the overall staff. In par-

ticular, it is looking for more technicians and engineers. Prior to this recruiting cam-

paign, however, the president of EL hired an outside consultant to assess employee

needs as well as the morale and overall effectiveness of the firm. The consultant has

been observing EL for about three weeks and has written up some notes of her

impressions and observations of the company.

Consultant’s Notes from Observations of Electro Logic

Facilities: Electro Logic (EL) is housed in three different buildings. Two are converted

houses, and one is an old school building. Senior managers and engineers are in the

school, and others are scattered between the houses.

Meetings: Weekly staff meetings are held in the main building to discuss objec-

tives and to formulate and review milestone charts.

Social interaction: A core group of employees interact frequently on a social

basis; for example, sports teams, parties. The administrative staff celebrates birth-

days at work. The president occasionally attends.

Work allocation: Engineers request various tasks from the support staff, which

consists of technicians and administrative unit personnel. There is obviously some

discretion used by the staff in assigning priorities to the work requests, based on rap-

port and desirability of the work.

356 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

Turnover: The highest turnover is among administrative personnel and

technicians. Exit interviews with engineers indicate they leave because of the com-

pany’s crisis-management style, better opportunities for career advancement and

security in larger organizations, and overall frustration with EL’s “pecking order.”

Engineers with the most responsibility and authority tend to leave.

Salary and benefits: In general, wages at EL are marginal by national and local

standards. A small group of scientists and engineers do make substantial salaries

and have a very attractive benefits package, including stock options. Salaries and

benefits for new engineers tend to be linked to the perceived level of their expertise.

Offices and facilities: Only EL’s president, vice president, and chief financial offi-

cer have their own offices. Engineers are grouped together in “pods” by project

assignment. There is very little privacy in these work areas, and the noise from the

shared printer is distracting. The head of administration shares a pod with the per-

sonnel director, facilities head, and the project controller. One to three secretaries

per building are located in or near the reception areas. The large building has an

employee lounge with three vending machines. There is also a coffee-and-tea station.

The smaller buildings have only a soft-drink machine in the reception area.

Consultant’s Interviews with Employees

After making these observations, the consultant requested interviews with a cross-section

of the staff for the purpose of developing a survey to be taken of all employees. Presented

below are excerpts from those interviews.

Pat Klausen, Senior Member of the Technical Staff

CONSULTANT: What is it about Electro Logic (EL) that gives you the most satisfaction?

PAT: I really enjoy the work. I mean, I’ve always liked to do research, and working

on VFVA is an incredible opportunity. Just getting to work with Steve (EL’s president

and VFVA’s inventor) again is exciting. I was his graduate student about six years ago,

you know. He really likes to work closely with his people—perhaps sometimes too

closely. There have been times when I could have done with a little less supervision.

CONSULTANT: What’s the least satisfying aspect of your work?

PAT: Probably the fact that I’m never quite sure we’ll be funded next month, given

the defense budget problems and the tentativeness of our research. I’ve got a family

to consider, and this place isn’t the most stable in terms of its financial situation.

Maybe it’ll change once we get more into commercial production. Who knows?

CONSULTANT: You’ve offered some general positives and negatives about EL.

Can you be more specific about day-to-day dealings? What’s good and bad about

working here on a daily basis?

PAT: You’re sure this isn’t going to get back to anyone? Okay. Well, in general I’m

not satisfied with the fact that too often we end up changing horses in the middle of

the stream, if you know what I mean. In the past seven months, three of my engineers

and four of my techs have been pulled off my project onto projects whose deadlines

were nearer than mine. Now I’m faced with a deadline, and I’m supposed to be get-

ting more staff. But I’ll have to spend so much time briefing them that it might make

more sense for me to just finish the project myself. On the other hand, Steve keeps

telling me that we have to be concerned with EL’s overall goals, not just our individual

concerns—you know, we have to be “team players,” “good members of the family.” It’s

kind of hard to deal with that, though, when deadlines are bearing down and you

know your butt’s on the line, team player or not. But if you go along with this kind of

stuff and don’t complain, the higher-ups treat you well. Still, it seems to me there’s

got to be a better way to manage these projects.