Whetten David A., Cameron Kim S. Developing management skills

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 337

The relevant diagnostic question here is, “Do

subordinates feel being a high performer is more

rewarding than being a low or average performer?”

Our discussion of this important element of an effec-

tive motivational program is based on two related

principles: (1) in general, managers should link

rewards to performance, rather than seniority or mem-

bership; and (2) managers should use discipline to

extinguish counterproductive behaviors and use

rewards to reinforce productive behaviors.

Use Rewards as Reinforcers

Here is the key to encouraging high performance:

behaviors that positively affect performance should be

contingently reinforced, using highly desirable rewards.

When rewards are linked to desired behaviors, they

reinforce (strengthen; increase the frequency of) that

behavior (Luthans & Stajkovic, 1999; Stajkovic &

Luthans, 2001). If an organization rewards all people

identically, or on some basis other than performance,

then high performers are likely to feel they are receiving

fewer “rewards” than they deserve. Obviously, high per-

formers are the key to the success of any organization.

Therefore, motivational schemes should be geared to

keeping this employee group satisfied. This observation

has led some organizational consultants to use the per-

formance ratings of individuals leaving an organization

as an index of the organization’s motivational climate.

Ed Lawler, one of the foremost authorities on

reward systems, underscored this point when he said,

“Often the early reward systems of an organization are

particularly important in shaping its culture. They

reinforce certain behavior patterns and signal how

highly valued different individuals are by the organiza-

tion. They also attract a certain type of employee and

in a host of little ways indicate what the organization

stands for and values” (Lawler, 2000a, p. 39).

The principle that rewards should be linked to per-

formance points to a need for caution regarding the prac-

tice in some organizations of minimizing distinctions

between workers. Some “progressive” organizations

have received considerable publicity for motivational

programs that include providing recreational facilities,

library services, day care, and attractive stock option pro-

grams for all employees. These organizations work hard

to reduce status distinctions by calling everyone “associ-

ates” or “partners,” eliminating reserved parking places,

and instituting a company uniform. Although there

are obvious motivational benefits from employees feel-

ing they are receiving basically the same benefits

(“perks”) regardless of seniority or level of authority, this

motivational philosophy, when carried to an extreme or

implemented indiscriminately, runs the risk of under-

mining the motivation of high performers. In an era of

egalitarianism, managers often overlook the vital link

between performance and rewards and as a conse-

quence find it difficult to attract and retain strong per-

formers (Pfeffer, 1995).

Fortunately, many firms recognize this pitfall. In a

survey, 42 percent of 125 organizations contacted indi-

cated they had made changes in their compensation

plan during the previous three years to achieve a better

link between pay and performance (Murlis & Wright,

1985). These respondents reported an interesting set

of pressures were prompting them to move in this

direction. Hard-charging, typically younger managers

were insisting on tighter control over employee perfor-

mance; executives were determined to “get more bang

for the buck” during periods of shrinking resources;

personnel managers were trying to reduce the number

of grievances focusing on “unfair” pay decisions; and

employees were trying to eliminate what they consid-

ered to be discrimination in the workplace.

A sampling of the creative methods firms are using

to establish closer connections between individual per-

formance and pay includes sales commissions that

include follow-up customer satisfaction ratings; pay

increases linked to the acquisition of new knowledge,

skills, and/or demonstrated competencies; compensat-

ing managers based on their ability to mentor new

group members and resolve difficult intergroup rela-

tionships; and linking the pay of key employees to the

accomplishment of new organizational goals or strate-

gic initiatives (Zingheim & Schuster, 1995).

In an attempt to examine the impact of one of

these innovative compensation programs, a study was

conducted in which the productivity, quality, and labor

costs of companies using skill-based pay were com-

pared with comparable firms. The results indicated

that firms using this type of pay plan benefited from

58 percent greater productivity, 16 percent lower

labor costs per part produced, and an 82 percent better

level of quality (Murray & Gerhart, 1998).

Technological constraints sometimes make it diffi-

cult to perfectly link individual performance with indi-

vidual rewards. For example, people working on an

automobile assembly line or chemists working on a

group research project have little control over their

personal productivity. In these situations, rewards

linked to the performance of the work group will foster

group cohesion and collaboration and partially satisfy

the individual members’ concerns about fairness

(Lawler, 1988, 2000b). When it is not possible to

338 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

assess the performance of a work group (work shift,

organizational department), it is advisable to consider

an organization-wide performance bonus. While the

merits and technical details of various group and orga-

nizational reward systems are beyond the scope of this

chapter, managers should link valued rewards and

good performance at the most appropriate level of

aggregation (Steers et al., 1996).

This discussion of the appropriate unit for measur-

ing and rewarding performance reminds us of the need

to take into consideration cultural values and expecta-

tions. For example, individuals from collectivist cul-

tures tend to see the group as the appropriate target for

improving performance (Graham & Trevor, 2000;

Parker, 2001; Triandis, 1994). This implies that in

addition to examining contextual factors that might

make it difficult to reward individual workers, it is also

important to take into consideration different cultur-

ally based assumptions about what is the appropriate

unit of analysis (group or individual) for measuring and

rewarding performance. If a manager of a sales depart-

ment is concerned about heading off a slump in new

orders that has traditionally occurred in the organiza-

tion during the coming eight-week period, and if she

has reason to believe department members would

respond positively to a bonus program targeting that

time period, she still has to decide if the bonus should

be linked to group performance or individual perfor-

mance. If this particular work unit consists of a mix-

ture of individuals holding collectivist and individualist

value perspectives, the manager should look for ways

to factor these conflicting perspectives into the design

of the bonus program.

It is also important to point out that nonfinancial

rewards (often treated as awards) need to be included

in an effective performance-reinforcing program.

Lawler argues firms will get the greatest motivational

impact from awards programs if they follow these

guidelines: (1) give the awards publicly, (2) use

awards infrequently, (3) embed them in a credible

reward process, (4) use the awards presentation to

acknowledge past recipients, and (5) make sure the

award is meaningful within the organization’s culture

(Lawler, 2000a, p. 72–73).

The Role of Managers’ Actions

as Reinforcers

An effective motivational program goes beyond the

design of the formal organizational reward system,

including such things as pay, promotions, and the

like. Managers must also recognize that their daily

interactions with subordinates constitute an important

source of motivation. It is difficult for even highly sensi-

tive and aware managers to understand fully the impact

of their actions on the behavior and attitudes of subordi-

nates. Unfortunately, some managers don’t even try to

monitor these effects. The danger of this lack of aware-

ness is it may lead to managerial actions that actually

reinforce undesirable behaviors in their subordinates.

This has been called “the folly of rewarding A while

hoping for B” (Kerr, 1995). For example, a vice president

of research and development with a low tolerance for

conflict and uncertainty may unwittingly undermine the

company’s avowed objective of developing highly cre-

ative products by punishing work groups that do not

exhibit unity or a clear, consistent set of priorities. Further,

while avowing the virtue of risk, the manager may punish

failure; while stressing creativity, he or she may kill the

spirit of the idea champion. These actions will encourage

a work group to avoid challenging projects, suppress

debate, and routinize task performance.

The dos and don’ts for encouraging subordinates to

assume more initiative, shown in Table 6.4, demonstrate

the power of managers’ actions in shaping behavior.

Actions and reactions that might appear insignificant to

the boss often have strong reinforcing or extinguishing

effects on subordinates. Hence the truism, “Managers

get what they reinforce, not what they want,” and its

companion, “People do what is inspected, not what is

expected.” Indeed, the reinforcing potential of man-

agers’ reactions to subordinates’ behaviors is so strong

that it has been argued, “The best way to change an indi-

vidual’s behavior in a work setting is to change his or her

manager’s behavior” (Thompson, 1978, p. 52). Given

the considerable leverage managers have over their sub-

ordinates’ motivation to reach optimal performance, it is

important that they learn how to use rewards and pun-

ishments effectively to produce positive, intended results

consistently.

Use Rewards and Discipline

Appropriately

Psychologists call the process of linking rewards and

punishments with behaviors in such a manner that the

behaviors are more or less likely to persist “operant con-

ditioning” (Komaki, Coombs, & Schepman, 1996). This

approach uses a wide variety of motivational strategies

that involve the presentation or withdrawal of positive

or negative reinforcers or the use of no reinforcement

whatsoever. Although there are important theoretical

and experimental differences in these strategies, such as

between negative reinforcement and punishment, for

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 339

Table 6.4 Guidelines for Fostering Subordinate Initiative

DO DON’T

Ask “How are we going to do this? What can I contribute Imply that the task is the employee’s total responsibility,

to this effort? How will we use this result?,” thus that they hang alone if they fail. Individual failure means

implying your joint stake in the work and results. organizational failure.

Use an interested, exploring manner, asking questions Play the part of an interrogator, firing questions as

designed to bring out factual information. rapidly as they can be answered. Also, avoid asking

questions that require only “yes” or “no” replies.

Keep the analysis and evaluation as much in the React to their presentations on an emotional basis.

employees’ hands as possible by asking for their best

judgment on various issues.

Present facts about organization needs, commitments, Demand a change or improvement in a preemptory tone

strategy, and so on, which permit them to improve, and of voice or on what appears to be an arbitrary basis.

interest them in improving what they propose to do.

Ask them to investigate or analyze further if you feel that Take their planning papers and cross out, change dates,

they have overlooked some points or overemphasized or mark “no good” next to certain activities.

others.

Ask them to return with their plans after factoring these Redo their plans for them unless their repeated efforts

items in. show no improvement.

the purposes of our discussion we will focus on three

types of management responses to employee behavior:

no response (ignoring), negative response (disciplining),

and positive response (rewarding).

The trickiest strategy to transfer from the psychol-

ogist’s laboratory to the manager’s work environment

is “no response.” Technically, what psychologists refer

to as “extinction” is defined as a behavior followed by

no response whatsoever. However, in most managerial

situations, people develop expectations about what is

likely to follow their actions based on their past experi-

ence, office stories, and so forth. Consequently, what is

intended as a nonresponse, or a neutral response, gen-

erally is interpreted as either a positive or negative

response. For example, if a subordinate comes into

your office complaining bitterly about a coworker, and

you attempt to discourage this type of behavior by

changing the subject or responding in a low, unrespon-

sive monotone voice, the subordinate may view this as

a form of rejection. If your secretary sheepishly slips a

delinquent report on your desk, and you ignore her

behavior because you are busy with other business,

she may be so relieved at not being reprimanded for

her tardiness that she actually feels reinforced.

These simple examples underscore an important

point: any behavior repeatedly exhibited in front of

a boss is being rewarded, regardless of the boss’s inten-

tion (“I don’t want to encourage that type of behavior, so

I’m purposely ignoring it”). By definition, if a behavior

persists, it is being reinforced. Thus, if an employee is

chronically late or continually submits sloppy work, the

manager must ask where the reinforcement for this

behavior is coming from. Consequently, while extinction

plays an important role in the learning process when

conducted in strictly controlled laboratory conditions, it

is a less useful technique in organizational settings

because the interpretation of a supposedly neutral

response is impossible to control. Thus, the focus of our

discussion will be on the proper use of disciplining and

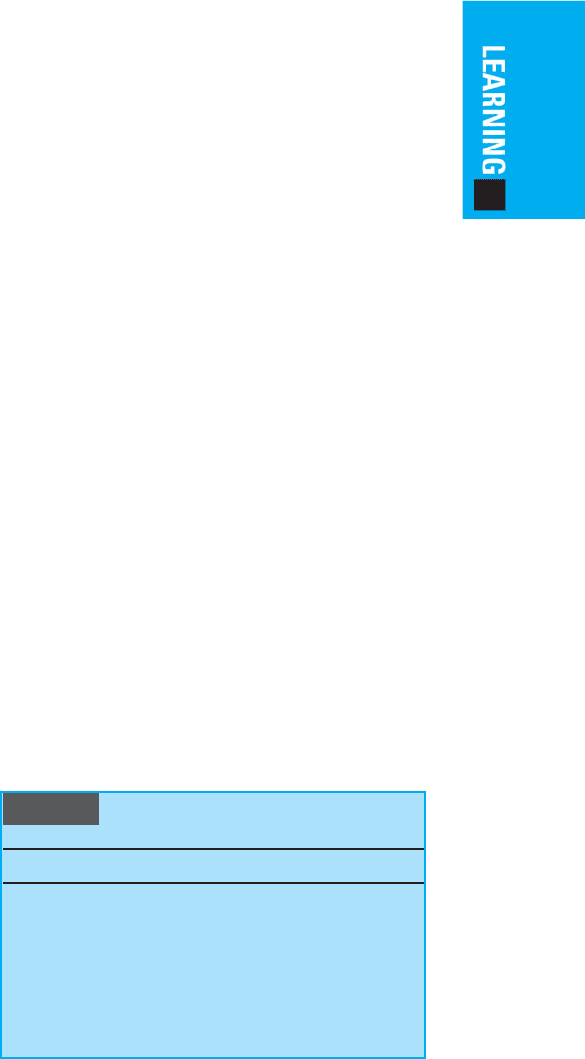

rewarding strategies, as shown in Figure 6.3.

The disciplining approach involves responding

negatively to an employee’s behavior with the inten-

tion of discouraging future occurrences of that behav-

ior. For example, if an employee is consistently late, a

supervisor may reprimand him with the hope that this

action will decrease the employee’s tardiness. Nagging

subordinates for their failure to obey safety regulations

is another example.

The rewarding approach consists of linking

desired behaviors with employee-valued outcomes.

When a management trainee completes a report in a

timely manner, the supervisor should praise his prompt-

ness. If a senior executive takes the initiative to solve a

thorny, time-consuming problem on her own, she

could be given some extra time to enjoy a scenic loca-

tion at the conclusion of a business trip. Unfortunately,

SOURCE: Reprinted with the permission of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from Putting Management Theories To Work by Marion S. Kellogg, revised by Irving Burstiner.

Copyright © 1979 by Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

340 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

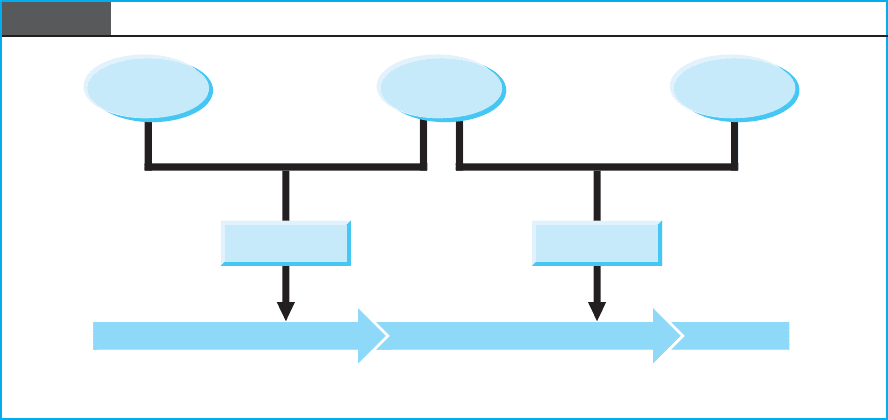

Figure 6.3 Behavior-Shaping Strategies

even simple rewards like these appear to be the excep-

tion, not the rule. Dr. Noelle Nelson, the author of a

book on the power of appreciation in the workplace

(2005), points out that according to U.S. Department of

Labor data, the number-one reason people leave their

job is that they do not feel appreciated. She also points

to a Gallup poll report that 65 percent of workers said

they didn’t receive a single word of praise or recogni-

tion during the past year. Elaborating on these data,

Nelson argues even the most energetic and effective

employees get worn down when they are rarely

acknowledged for their good work and only singled out

when they make mistakes.

Disciplining and rewarding are both viable and use-

ful techniques and each has its place in the effective man-

ager’s motivational repertoire. However, as Figure 6.3

shows, each technique is associated with different

behavior-shaping goals. Discipline should be used to

extinguish unacceptable behaviors. However, once an

individual’s behavior has reached an acceptable level,

negative responses will not push the behavior up to the

exceptional level. It is difficult to encourage employees to

perform exceptional behaviors through nagging, threat-

ening, or related forms of discipline. The left-hand side of

Figure 6.3 shows that subordinates work to remove an

aversive response rather than to gain a desired reward.

Only through positive reinforcement do employees have

control over achieving what they want and, therefore,

the incentive to reach a level of exceptional performance.

The emphasis in Figure 6.3 on matching discipline

and rewards with unacceptable and acceptable behaviors,

respectively, highlights two common misapplications

of reinforcement principles. First, it helps us better

understand why top performers frequently get upset

because they feel “management is too soft on those guys

who are always screwing things up.” Thinking it is good

management practice always to be upbeat and opti-

mistic and to discourage negative interactions, some

managers try to downplay the seriousness of mistakes

by ignoring them, by trying to temper the conse-

quences by personally fixing errors, or by encouraging

the high performers to be more tolerant and patient.

Other managers feel so uncomfortable with confronting

personal performance problems they are willing to over-

look all but the most egregious mistakes.

Although there is a lot to be said for managers

having a positive attitude and giving poor performers

the benefit of the doubt, their failure to reprimand and

redirect inappropriate behaviors leads to two undesir-

able outcomes: the work unit’s morale is seriously

threatened, and the poor performers’ behaviors are not

improved.

Just as some managers find it unpleasant to issue

reprimands for poor performance, other managers have

difficulty praising exceptional performance. As a result,

subordinates complain, “Nothing ever satisfies him.”

This second misapplication of the negative-response

behavior-shaping strategy is just as dysfunctional as the

indiscriminate use of praise. These managers mistakenly

believe the best way to motivate people is by always

keeping expectations a little higher than their subordi-

nates’ best performance and then chiding them for their

imperfection. In the process, they run the risk of burn-

ing out their staff or inadvertently encouraging lower

Discipline

Unacceptable

Behavior

Reward

Reprimand Redirect Reinforce

–

Acceptable

Behavior

0

Exceptional

Behavior

+

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 341

performance (“We’ll get chewed out anyway, so why try

so hard?”). Furthermore, the irony is that this method

creates a competitive, self-defeating situation in which

subordinates look forward to the boss’s making

mistakes—the bigger the better!

Unfortunately, many managers genuinely believe

this is the best way to manage in all situations. They

define their role as that of a “sheepdog,” circling the

perimeter of the group, nipping at the heels of those

who begin to stray. They establish a fairly broad range

of acceptable behaviors and then limit their interactions

with employees to barking at those who exceed the

boundaries. This negative, desultory style of manage-

ment creates a demoralizing work environment and

does not foster exceptional performance. Instead,

workers are motivated to stay out of the boss’s way and

to avoid doing anything unusual or untried. Innovation

and involvement are extinguished, and mundane per-

formance becomes not only acceptable but desirable.

Having looked at the consequences of misapplying

rewards and discipline, we will now turn our attention

to the proper use of behavior-shaping techniques. The

mark of exceptional managers is their ability to foster

exceptional behavior in their subordinates. This is best

accomplished by using a nine-step behavior-shaping

process, which can be applied to the full range of

subordinates’ behaviors. They can be used either to

make unacceptable behaviors acceptable or to trans-

form acceptable behaviors into exceptional ones. They

are designed to avoid the harmful effects typically

associated with the improper use of discipline discussed

in the previous section (Wood & Bandura, 1989). They

also ensure the appropriate use of rewards.

Strategies for Shaping Behavior

Table 6.5 shows the nine steps for improving behav-

iors. These are organized into three broad initiatives:

reprimand, redirect, and reinforce. As shown in

Figure 6.3, steps 1 through 6 (reprimand and redirect)

are used to extinguish unacceptable behaviors and

replace them with acceptable ones. Steps 4 through 9

(redirect and reinforce) are used to transform accept-

able behaviors into exceptional behaviors.

An important principle to keep in mind when

issuing a reprimand is discipline should immediately

follow the offensive behavior and focus exclusively on

the specific problem. This is not an appropriate time to

dredge up old concerns or make general, unsubstanti-

ated accusations. The focus of the discussion should be

on eliminating a problem behavior, not on making

the subordinate feel bad. This approach increases

the likelihood the employee will associate the negative

response with a specific act rather than viewing it

as a generalized negative evaluation, which will red-

uce the hostility typically engendered by being

reprimanded.

Second, it is important to redirect inappropriate

behaviors into appropriate channels. It is important

that people being reprimanded understand how they

Table 6.5 Guidelines for Improving Behaviors

Reprimand

1. Identify the specific inappropriate behavior. Give examples. Indicate that the action must stop.

2. Point out the impact of the problem on the performance of others, on the unit’s mission, and so forth.

3. Ask questions about causes and explore remedies.

Redirect

4. Describe the behaviors or standards you expect. Make sure the individual understands and agrees that these are

reasonable.

5. Ask if the individual will comply.

6. Be appropriately supportive. For example, praise other aspects of their work, identify personal and group benefits

of compliance; make sure there are no work-related problems standing in the way of meeting your expectations.

Reinforce

7. Identify rewards that are salient to the individual.

8. Link the attainment of desirable outcomes with incremental, continuous improvement.

9. Reward (including using praise) all improvements in performance in a timely and honest manner.

342 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

can receive rewards in the future. The process of redi-

rection reduces the despair that occurs when people

feel they are likely to be punished no matter what they

do. If expected behaviors are not made clear, then

workers may stop the inappropriate behavior but feel

lost, not knowing how to improve. Keep in mind the

ultimate goal of any negative feedback should be to

transform inappropriate behaviors into appropriate

behaviors, in contrast to simply punishing a person

for causing a problem or making the boss look bad.

The lingering negative effects of a reprimand will

quickly wear off if the manager begins using rewards

to reinforce desirable behaviors shortly thereafter.

This goal can be achieved only if workers know how

they can receive positive outcomes and perceive that

the available rewards are personally salient (a subject

we’ll discuss in detail shortly).

Experienced managers know it is just as difficult

to transform acceptable behaviors into exceptional

ones. Helping an “OK, but uninspired” subordinate

catch the vision of moving up to a higher level of

desire and commitment can be very challenging. This

process begins at step 4 (redirect) by first clearly

describing the goal or target behavior. The goal of

skilled managers is to avoid having to administer any

negative responses and especially to avoid trial-and-

error learning among new subordinates. This is done

by clearly laying out their expectations and collabora-

tively establishing work objectives. In addition, it is a

good idea to provide an experienced mentor, known

for exceptional performance, as a sounding board and

role model.

Foster Intrinsic Outcomes

So far our discussion of the Performance → Outcomes

link has focused on extrinsic outcomes. These are

things like pay and promotions and praise that are con-

trolled by someone other than the individual performer.

In addition, the motivating potential of a task is affected

by its associated intrinsic outcomes, which are experi-

enced directly by an individual as a result of successful

task performance. They include feelings of accomplish-

ment, self-esteem, and the development of new skills.

Although our emphasis has been on the former, a com-

plete motivational program must take into account both

types of outcomes.

Effective managers understand that the person-job

interface has a strong impact on work performance. No

matter how many externally controlled rewards man-

agers use, if individuals find their jobs uninteresting and

unfulfilling, performance will suffer. This is particularly

true for certain individuals. For example, researchers

have discovered that the level of job satisfaction

reported by highly intelligent people is closely linked to

the degree of difficulty they encounter in performing

their work (Ganzach, 1998). In addition, attention to

intrinsic outcomes is particularly important in situations

in which organizational policies do not permit a close

link between performance and rewards; for example, in

a strong seniority personnel system. In these cases, it is

often possible to compensate for lack of control over

extrinsic outcomes by fine-tuning the person-job fit.

Motivating Workers

by Redesigning Work

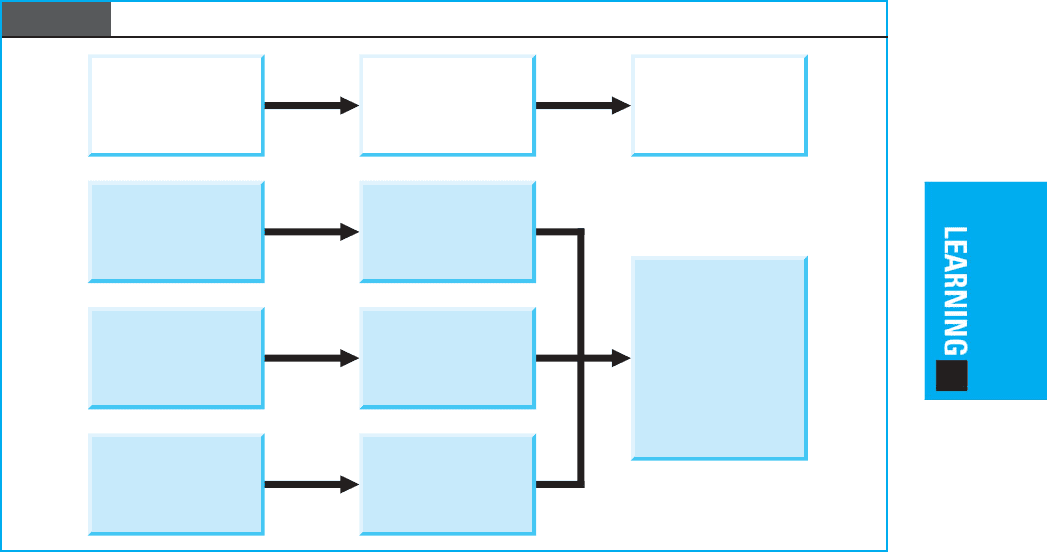

Work design is the process of matching job characteris-

tics and workers’ skills and interests. One popular work-

design model proposes that particular job dimensions

cause workers to experience specific psychological

reactions called “states.” In turn, these psychologi-

cal reactions produce specific personal and work out-

comes. Figure 6.4 shows the relationship between the

core job dimensions, the critical psychological states

they produce, and the resulting personal and work

outcomes (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). A variety

of empirical research has found the five core job

dimensions—skill variety, task identity, task signifi-

cance, autonomy, and feedback—are positively related

to job satisfaction.

The more variety in the skills a person can use in

performing work, the more the person perceives the

task as meaningful or worthwhile. Similarly, the more an

individual can perform a complete job from beginning to

end (task identity) and the more the work has a direct

effect on the work or lives of other people (task signifi-

cance), the more the employee will view the job as

meaningful. On the other hand, when the work requires

few skills, only part of a task is performed, or there

seems to be little effect on others’ jobs, experienced

meaningfulness is low.

The more autonomy in the work (freedom to

choose how and when to do particular jobs), the more

responsibility workers feel for their successes and fail-

ures. Increased responsibility results in increased com-

mitment to one’s work. Autonomy can be increased by

instituting flexible work schedules, decentralizing

decision making, or selectively removing formalized

controls, such as the ringing of a bell to indicate the

beginning and end of a workday.

Finally, the more feedback individuals receive about

how well their jobs are being performed, the more

knowledge of results they have. Knowledge of results

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 343

Figure 6.4

Designing Highly Motivating Jobs

SOURCE: Hackman/Oldham, Work Redesign, © 1980. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ.

permits workers to understand the benefits of the jobs

they perform. Employees’ knowledge of results may be

enhanced by increasing their direct contact with clients

or by giving them feedback on how their jobs fit in and

contribute to the overall operation of the organization.

By enhancing the core job dimensions and

increasing critical psychological stages, employees’ job

fulfillment is increased. Job fulfillment (high internal

work motivation) is associated with other outcomes

valued by management. These include high-quality

work performance, high employee satisfaction with

their jobs, and low absenteeism and turnover.

Employees who have well-designed jobs enjoy doing

them because they are intrinsically satisfying.

This discussion of work design suggests five man-

agerial action guidelines that can help increase desirable

personal and work outcomes. These are summarized in

Table 6.6. The first one is to combine tasks. A combina-

tion of tasks is by definition a more challenging and

complex work assignment. It requires workers to use a

wider variety of skills, which makes the work seem

more challenging and meaningful. Telephone directo-

ries at the former Indiana Bell Telephone company used

to be compiled in 21 steps along an assembly line.

Through job redesign, each worker was given responsi-

bility for compiling an entire directory.

A related managerial principle is to form identifiable

work units so task identity and task significance can be

increased. Clerical work in a large insurance firm was

handled by 80 employees organized by functional task

(e.g., opening the mail, entering information into the

computer, sending out statements). Work was assigned,

based on current workload, by a supervisor over each

functional area. To create higher levels of task identity

and task significance, the firm reorganized the clerical

staff into eight self-contained groups. Each group

handled all business associated with specific clients.

The third guideline for enhancing jobs is to

establish client relationships. A client relationship

involves an ongoing personal relationship between an

employee (the producer) and the client (the con-

sumer). The establishment of this relationship can

increase autonomy, task identity, and feedback. Take,

for example, research and development (R&D) employ-

ees. While they may be the ones who design a prod-

uct, feedback on customer satisfaction generally is

routed through their managers or a separate customer

relations unit. At Caterpillar, Inc., members of each

• High internal

work motivation

• High-quality work

performance

• High satisfaction

with the work

• Low absenteeism

and turnover

PERSONAL AND

WORK OUTCOMES

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

STATES

CORE JOB

DIMENSIONS

Skill variety

Task identity

Task significance

Autonomy

Knowledge of

the actual

results of work

activities

Feedback

Experienced

meaningfulness

of work

Experienced

responsibility

for outcomes

of the work

344 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

division’s R&D group are assigned to make regular con-

tacts with their major clients.

The fourth suggestion, increase authority, refers to

granting more authority for making job-related decisions

to workers. When we speak here of “vertical,” we refer

to the distribution of power between a subordinate and a

boss. As supervisors delegate more authority and respon-

sibility, their subordinates’ perceived autonomy, task sig-

nificance, and task identity increase. Historically, workers

on auto assembly lines have had little decision-making

authority. However, in conjunction with increased

emphasis on quality, many plants now allow workers to

adjust their equipment, reject faulty materials, and even

shut down the line if a major problem is evident.

The final managerial suggestion is to open feed-

back channels. Workers need to know how well or

how poorly they are performing their jobs if any kind

of improvement is expected. Thus, it is imperative

they receive timely and consistent feedback, which

allows them to make appropriate adjustments in their

behavior so they can receive desired rewards. The

traditional approach to quality assurance in American

industry is to “inspect it in.” A separate quality assur-

ance group is assigned to check the production team’s

quality. The emerging trend is to give producers

responsibility for checking their own work. If it doesn’t

meet quality standards, they immediately fix the

defect. Following this procedure, workers receive

immediate feedback on their performance.

A different approach to job design focuses on

matching individuals’ “deeply embedded life interests”

with the task characteristics of their work (Butler &

Waldroop, 1999). The proponents of this approach

argue that for too long people have been advised to

select careers based on what they are good at, rather

than what they enjoy. The assumption behind this

advice is that individuals who excel at their work are

satisfied with their jobs. However, critics of this perspec-

tive argue many professionals are so well educated and

achievement oriented they could succeed in virtually

any job. This suggests people stay in jobs because they

become involved in activities consistent with their long-

held, emotionally driven passions, intricately entwined

with their personality.

Setting aside the differences among the various

approaches to matching workers and their work, the

overall record of job redesign interventions is impressive.

In general, firms typically report a substantial increase in

productivity, work quality, and worker satisfaction

(reflected in lower rates of absenteeism). For example,

the Social Security Administration increased productivity

23.5 percent among a group of 50 employees; General

Electric realized a 50 percent increase in product quality

as a result of a job redesign program; and the absen-

teeism rate among data-processing operators at Travelers

Insurance decreased 24 percent (Kopelman, 1985).

In summary, managers should recognize both

extrinsic and intrinsic outcomes are necessary ingredi-

ents of effective motivational programs. For example,

because most people desire interesting and challenging

work activities, good wages and job security will do

little to overcome the negative effects of individuals’

feeling that their abilities are being underutilized.

In addition, recognizing individual preferences for

outcomes vary, managers should not assume a narrow-

gauged, outcomes-contingent, performance-reinforcing

motivation program will satisfy the needs and interests

of a broad group of individuals. This brings us to the

subject of reward salience.

PROVIDE SALIENT REWARDS

Having established a link between performance and

outcomes (rewards and discipline) as part of an integra-

tive motivational program, we now move to the final

link in the four-factor model of motivation: Outcomes →

Satisfaction. In the following sections we will discuss

the three remaining elements of our motivational pro-

gram, as shown in Table 6.2. Each of these elements has

been shown to affect how satisfied individuals are with

their work-related outcomes, and as a set they help us

understand the key distinction between a reward and a

Table 6.6 Strategies for Increasing the Motivational Potential of Assigned Work

Combine tasks → Increase skill variety and task significance

Form identifiable work units → Increase task identity and significance

Establish client relationships → Increase autonomy, task identity, and feedback

Increase authority → Increase autonomy, task significance, and task identity

Open feedback channels → Increase autonomy and feedback

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 345

reinforcer. The likelihood a “reward” (so labeled by

the reward giver) will actually reinforce a specific

performance-enhancing behavior depends on the extent

to which the reward recipient: (1) actually values the

specific outcome, (2) believes that the reward allocation

process was handled fairly, and (3) receives the reward

in a timely manner.

We begin this discussion, with diagnostic question 4,

“Do subordinates feel the rewards used to encourage

high performance are worth the effort?” One of the

biggest mistakes that can be made in implementing a

“reward program” is assuming managers understand

their subordinates’ preferences. For example, while it

is assumed most people prefer cash incentives, accord-

ing to a 2004 study conducted by the University of

Chicago, performance increases much faster when it is

linked to noncash rewards (14.6 percent increase

for cash vs. 38.6 percent increase for noncash) (Cook,

2005, p. 6). On an individual level, the manager’s lament

“What does Joe expect, anyway? I gave him a bonus,

and he’s still complaining to other members of the

accounting department that I don’t appreciate his

superior performance,” indicates an apparent miscalcu-

lation of what Joe really values. This miscalculation also

suggests the manager needs a better understanding of

the relationship between personal needs and personal

motivation.

Personal Needs and

Personal Motivation

One of the most enduring theories of motivation is

based on our scientific understanding of human needs.

One way to categorize the various theories of human

needs is by whether the theories assume that needs are

arranged in a hierarchical fashion. The logic of a hier-

archical needs model is people are motivated to sat-

isfy their most basic unfulfilled need. That is, until a

lower-level need has been satisfied, a higher-level need

won’t become activated. Probably the best-known

example of a hierarchical needs model was proposed

by Abraham Maslow (1970). He posited five levels of

needs, beginning with physiological, followed by

safety, belongingness, esteem, and self-actualization.

Clay Alderfer proposed a more parsimonious hierarchi-

cal model (1977) that contained only three levels, or

categories: existence, relatedness, and growth. Like

Maslow, Alderfer proposed satisfied needs become

dormant unless a dramatic shift in circumstances

increases their salience. For example, a middle-level

executive who is fired during a hostile takeover may

suddenly find her interest in personal growth is

overwhelmed by a pressing need for security. The

problem with hierarchical needs theories is although

they help us understand general developmental

processes, from child to adult, they aren’t very useful

for understanding the day-to-day motivation levels of

adult employees. A comparison of these hierarchical

needs models is shown in Table 6.7.

An alternative perspective can be found in Murray’s

manifest needs model (McClelland, 1971, p. 13).

Murray proposes individuals can be classified according

to the strengths of their various needs. In contrast to hier-

archical models, in which needs are categorized based on

their inherent strength (hunger is a stronger need than

self-actualization), Murray poses people have divergent

and often conflicting needs. Murray proposes about two

dozen needs, but later studies have suggested only three

or four of them are relevant to the workplace, including

the needs for achievement, affiliation, and power.

Another important distinction of Murray’s conception is

his belief these needs are primarily learned, rather than

inherited, and they are activated by cues from the envi-

ronment. That is, if a person has a high need for achieve-

ment it will become manifest, or an active motivational

force, only if the environment cues achievement-

oriented behavior.

The need for achievement is defined as “behav-

ior toward competition with a standard of excel-

lence” (McClelland, Arkinson, Clark, & Lowell, 1953,

p. 111). This suggests individuals with a high need for

achievement would be characterized by: (1) a tendency

to set moderately difficult goals, (2) a strong desire to

assume personal responsibility for work activities, (3) a

single-minded focus on accomplishing a task, and (4) a

strong desire for detailed feedback on task performance.

The level of a person’s need for achievement (high to

low) has been shown to be a good predictor of job per-

formance. In addition, it is highly correlated with a per-

son’s preference for an enriched job with greater respon-

sibility and autonomy.

Table 6.7 Comparison of Hierarchical

Needs Theories

MASLOW ALDERFER

Self-actualization Growth

Esteem

Belongingness Relatedness

Safety

Physiological Existence

346 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

The second of Murray’s needs, need for affiliation,

involves attractions to other individuals in order to feel

reassured and acceptable (Birch & Veroff, 1966, p. 65). It

has been suggested that people with a high need for

affiliation are characterized by: (1) a sincere interest in

the feelings of others; (2) a tendency to conform to the

expectations of others, especially those whose affiliation

they value; and (3) a strong desire for reassurance and

approval from others. One would expect individuals with

a high need for affiliation to gravitate toward jobs that

provide a high degree of interpersonal contact. It is useful

to point out in contrast to the need for achievement, the

need for affiliation does not seem to be correlated with

job performance.

Rounding out Murray’s model is the need for

power, which represents a desire to influence others

and to control one’s environment. Individuals with a

high need for power seek leadership positions and tend

to influence others in a fairly open, direct manner.

McClelland and Burnham (2003) suggest there are two

manifestations of the general need for power. Individuals

with a high need for personal power tend to seek power

and influence for its own sake. To them, control and

dominance and conquest are important indicators of per-

sonal efficacy. These leaders inspire their subordinates to

perform heroic feats, but for the sake of the leader, not

the organization. In contrast, individuals with high instit-

utional power needs are more oriented toward using

their influence to advance the goals of the group or orga-

nization. These individuals are described by McClelland

as follows: (1) they are organization minded, feeling per-

sonally responsible for advancing the purposes of the

organization; (2) they enjoy work and accomplishing

tasks in an orderly fashion; (3) they are often willing to

sacrifice their own self-interests for the good of the orga-

nization; (4) they have a strong sense of justice and

equity; and (5) they seek expert advice and are not

defensive when their ideas are criticized.

Using Need Theory to Identify

Personally Salient Outcomes

An understanding of need theory helps managers

understand whether organizational rewards are salient

reinforcers for specific individuals. Simply put, if a

reward satisfies an activated personal need, it can be

used to reinforce desired individual behaviors. In prac-

tice, this means managers need to understand what

motivates each of their subordinates. Table 6.8

demonstrates the difficulty of this task. These research

results highlight differences in what various types

of organizational members tend to see as highly

motivating aspects of their work. For example, while

on average the employees in this study placed the

highest value on “interesting work” and the lowest

value on “sympathetic help with personal problems,”

we see significant differences in the ratings for these

two outcomes across gender, age, and income cate-

gories. It is easy to spot equally disparate outcome pref-

erences expressed by different groups of workers for

many of the other benefits and rewards, in the left-

hand column, commonly used by business firms to

attract, retain, and motivate employees.

In the abstract it is not surprising to learn individuals

with different demographic and economic profiles have

different needs and, thus, bring different expectations to

the workplace. The relevance of this data for effective

motivational practices is underscored by a parallel

research study suggesting that managers are not particu-

larly good at predicting how their subordinates would

rank the outcomes shown in Table 6.8 (LeDue, 1980).

More particularly, this research suggests that managers

tend to base their answers to the question, “What moti-

vates your subordinates?” on two faulty assumptions.

First, they assume the outcome preferences among their

subordinates are fairly homogenous, and second, they

assume their personal outcome preferences are similar to

those held by their subordinates. Knowing this, the data

shown in Table 6.8 illustrates how easy it is for managers

with a certain gender, age, and income profile to system-

atically misread the salient needs of subordinates charac-

terized by a different profile. Furthermore, it is not

difficult to imagine individual circumstances that would

result in a person’s preferences being significantly differ-

ent from those of others with a similar demographic and

economic profile. In summary, this data underscores

the importance of managers getting to know their subor-

dinates well enough that they can effectively match

individual and group performance expectations with

personally salient outcomes.

The importance of gaining this person-specific

information is illustrated in the case of a stockbroker

who was promoted to office manager because upper

management in the home office felt he was “the most

qualified and most deserving.” Unfortunately, they

failed to ask him if he wanted to be promoted. They

assumed that because they had worked hard to qualify

for their management positions, all hard workers were

similarly motivated. Two weeks after receiving his

“reward” for outstanding performance, the supersalesman-

turned-manager was in the hospital with a stress-related

illness.

Effective managers gain information about active

needs and personal values through frequent, supportive,