Whetten David A., Cameron Kim S. Developing management skills

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 327

workers are assigned to irregular schedules (often

involving night work), commonly known as shift work.

In a recent article on the challenges facing shift workers,

the story was told of a supervisor who sought permis-

sion from the human resources department to fire a

worker because he didn’t “stay on task,” often walked

around talking to others, and occasionally fell asleep on

the job. Research on shift workers suggests the need to

look beyond a simplistic “poor performance equals low

motivation and commitment” explanation for this

worker’s unacceptable behavior. For example, shift

workers sleep two to three hours less per night than day

workers, they are four to five times more likely to expe-

rience digestive disorders due to eating the wrong foods

at the wrong times, chronic fatigue is reported by

80 percent of shift workers, 75 percent of shift workers

report feeling isolated on the job, and drug and alcohol

abuse are three times greater among permanent shift

workers (Perry, 2000).

To avoid falling prey to simplistic, ill-informed

diagnoses of work performance problems, managers

need a model, or framework, to guide their inquiry

process. Various organizational scholars (e.g., Gerhart,

2003; Steers, Porter, & Bigley, 1996; Vroom, 1964)

have summarized the determinants of task perfor-

mance as follows:

Performance

=

Ability

×

Motivation (Effort)

where

Ability

=

Aptitude

×

Training

×

Resources

Motivation

=

Desire

×

Commitment

According to these formulas, performance is the

product of ability multiplied by motivation, ability is

the product of aptitude multiplied by training and

resources, and motivation is the product of desire

and commitment. The multiplicative function in these

formulas suggests that all elements are essential. For

example, workers who have 100 percent of the moti-

vation and 75 percent of the ability required to perform

a task can perform at an above-average rate. However,

if these individuals have only 10 percent of the ability

required, no amount of motivation will enable them to

perform satisfactorily.

Aptitude refers to the native skills and abilities a

person brings to a job. These involve physical and men-

tal capabilities; but for many people-oriented jobs, they

also include personality characteristics. Most of our

inherent abilities can be enhanced by education and

training. Indeed, much of what we call native ability in

adults can be traced to previous skill-enhancement

experiences, such as modeling the social skills of

parents or older siblings. Nevertheless, it is useful to

consider training as a separate component of ability,

since it represents an important mechanism for improv-

ing employee performance. Ability should be assessed

during the job-matching process by screening appli-

cants against the skill requirements of the job. If an

applicant has minor deficiencies in skill aptitude but

many other desirable characteristics, an intensive train-

ing program can be used to increase the applicant’s

qualifications to perform the job.

Our definition of ability is broader than most. We

are focusing on the ability to perform, rather than the

performer’s ability. Therefore, our definition includes

a third, situational component: adequate resources.

Frequently, highly capable and well-trained individuals

are placed in situations that inhibit job performance.

Specifically, they aren’t given the resources (technical,

personnel, political) to perform assigned tasks effectively.

Motivation represents an employee’s desire and

commitment to perform and is manifested in job-

related effort. Some people want to complete a task but

are easily distracted or discouraged. They have high

desire but low commitment. Others plod along with

impressive persistence, but their work is uninspired.

These people have high commitment but low desire.

The first diagnostic question that must be asked

by the supervisor of a poor performer is whether the

person’s performance deficiencies stem from lack of

ability or lack of motivation. Managers need four

pieces of information in order to answer this question

(Michener, Fleishman, & Vaske, 1976):

1. How difficult are the tasks being assigned to

the individual?

2. How capable is the individual?

3. How hard is the individual trying to succeed at

the job?

4. How much improvement is the individual

making?

In terms of these four questions, low ability is gen-

erally associated with very difficult tasks, overall low

individual ability, evidence of strong effort, and lack of

improvement over time.

The answer to the question “Is this an ability or

motivation problem?” has far-reaching ramifications for

manager-subordinate relations. Research on this topic

has shown that managers tend to apply more pressure

to a person if they feel that the person is deliberately

not performing up to expectations, rather than not per-

forming effectively due to external, uncontrollable

328 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

forces. Managers sometimes justify their choice of a

forceful influence strategy on the grounds that the sub-

ordinate has a poor attitude, is hostile to authority, or

lacks dedication.

Unfortunately, if the manager’s assessment is incor-

rect and poor performance is related to ability rather

than motivation, the response to increased pressure

will worsen the problem. If poor performers feel that

management is insensitive to their problems—that

they lack resources, adequate training, or realistic

time schedules—they may respond counterproduc-

tively to any tactics aimed at increasing their

effort. Quite likely they will develop a motivational

problem—that is, their desire and commitment will

decrease—in response to management’s insensitive,

“iron-fisted” actions. Seeing this response, manage-

ment will feel that their original diagnosis is con-

firmed, and they will use even stronger forms of

influence to force compliance. The resulting vicious

cycle is extremely difficult to break and underscores

the high stakes involved in accurately diagnosing poor

performance problems.

In this chapter, we will examine the two compo-

nents of performance in more detail, beginning with

ability. We’ll discuss manifestations of low ability and

poor motivation, their causes, and some proposed

remedies. We’ll devote more attention to motivation,

since motivation is more central to day-to-day

manager-subordinate interactions. While ability tends

to remain stable over long periods of time, motivation

fluctuates; therefore, it requires closer monitoring and

frequent recharging.

Enhancing Individuals’ Abilities

A person’s lack of ability might inhibit good performance

for several reasons. Ability may have been assessed

improperly during the screening process prior to

employment, the technical requirements of a job may

have been radically upgraded, or a person who

performed very well in one position may have been pro-

moted into a higher-level position that is too demanding.

(The Peter Principle states that people are typically pro-

moted one position above their level of competence.) In

addition, human and material resource support may

have been reduced because of organizational budget

cutbacks.

As noted by Quick (1977, 1991), managers

should be alert for individuals who show signs of abil-

ity deterioration. Following are three danger signals for

management positions:

1. Taking refuge in a specialty. Managers

show signs of insufficient ability when they

respond to situations not by managing, but by

retreating to their technical specialty. This

often occurs when general managers who feel

insecure address problems outside their area of

expertise and experience. Anthony Jay, in

Management and Machiavelli (1967), dubs

this type of manager “George I,” after the King

of England who, after assuming the throne,

continued to be preoccupied with the affairs of

Hanover, Germany, whence he had come.

2. Focusing on past performance. Another

danger sign is measuring one’s value to the

organization in terms of past performance or

on the basis of former standards. Some cavalry

commanders in World War I relied on their

outmoded knowledge of how to conduct suc-

cessful military campaigns and, as a result,

failed miserably in mechanized combat. This

form of obsolescence is common in organiza-

tions that fail to shift their mission in response

to changing market conditions.

3. Exaggerating aspects of the leadership

role. Managers who have lost confidence in

their ability tend to be very defensive. This

often leads them to exaggerate one aspect of

their managerial role. Such managers might

delegate most of their responsibilities because

they no longer feel competent to perform them

well. Or they might become nuts-and-bolts

administrators who scrutinize every detail to

an extent far beyond its practical value. Still

others become “devil’s advocates,” but rather

than stimulating creativity, their negativism

thwarts efforts to change the familiar.

There are five principal tools available for over-

coming poor performance problems due to lack of abil-

ity: resupply, retrain, refit, reassign, and release. We

will discuss these in the order in which a manager

should consider them.

Once a manager has ascertained that lack of ability

is the primary cause of someone’s poor performance, a

performance review interview should be scheduled to

explore these options, beginning with resupplying and

retraining. Unless the manager has overwhelming evi-

dence that the problem stems from low aptitude, it is

wise to assume initially that it is due to a lack of

resources or training. This gives the subordinate the

benefit of the doubt and reduces the likely defensive

reaction to an assessment of inadequate aptitude.

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 329

The resupply option focuses on the support needs

of the job, including personnel, budget, and political

clout. Asking “Do you have what you need to perform

this job satisfactorily?” allows the subordinate to express

his or her frustration related to inadequate support.

Given the natural tendency for individuals to blame

external causes for their mistakes, managers should

explore their subordinates’ complaints about lack of sup-

port in detail to determine their validity. Even if employ-

ees exaggerate their claims, starting your discussion of

poor performance in this manner signals your willing-

ness to help them solve the problem from their perspec-

tive rather than to find fault from your perspective.

The next least threatening option is to retrain.

American companies with more than 100 employees

budgeted in excess of $60 billion for formal training. To

deliver this training, these firms spent $42 billion

on corporate trainers and an additional $14.3 billion on

commercial trainers (Reese, 1999; Tomlinson, 2002).

This is a sizeable expenditure for American corpora-

tions, but the reasons for these expenditures are clear.

First of all, technology is changing so quickly that

employees’ skills can soon become obsolete. It has been

estimated that 50 percent of employees’ skills become

outdated within three to five years (Moe & Blodget,

2000). Second, employees will typically fill a number of

different positions throughout their careers, each

demanding different proficiencies. Finally, demographic

changes in our society will lead to an increasingly older

workforce. In order for companies to remain competi-

tive, more and more of them must retrain their older

employees.

Training programs can take a variety of forms. For

example, many firms are using computer technology

more in education. This can involve interactive techni-

cal instruction and business games that simulate

problems likely to be experienced by managers in the

organization. More traditional forms of training include

subsidized university courses and in-house technical or

management seminars. Some companies have experi-

mented with company sabbaticals to release managers

or senior technical specialists from the pressures of

work so they can concentrate on retooling. The most

rapidly increasing form of training is “distance learn-

ing,” in which formal courses are offered over the

Internet. Web-based corporate learning is expected to

soon top $11 billion (Moe & Blodget, 2000). In a recent

report, the U.S. Department of Education stated that

1,680 academic institutions offered 54,000 online

courses in 1998—for which 1.6 million students

enrolled. That marked a 70 percent increase since

1995 (Boehle, Dobbs, & Stamps, 2000).

In many cases, resupplying and retraining are

insufficient remedies for poor performance. When this

happens, the next step should be to explore refitting

poor performers to their task assignments. While the

subordinates remain on the job, the components of their

work are analyzed, and different combinations of tasks

and abilities that accomplish organizational objectives

and provide meaningful and rewarding work are

explored. For example, an assistant may be brought in

to handle many of the technical details of a first-line

supervisor’s position, freeing up more time for the super-

visor to focus on people development or to develop a

long-term plan to present to upper management.

If a revised job description is unworkable or inad-

equate, the fourth alternative is to reassign the poor

performer, either to a position of less responsibility or

to one requiring less technical knowledge or interper-

sonal skills. For example, a medical specialist in a hos-

pital who finds it increasingly difficult to keep abreast

of new medical procedures but has demonstrated man-

agement skills might be shifted to a full-time adminis-

trative position.

The last option is to release. If retraining and cre-

ative redefinition of task assignments have not worked

and if there are no opportunities for reassignment in

the organization, the manager should consider releas-

ing the employee from the organization. This option is

generally constrained by union agreements, company

policies, seniority considerations, and government reg-

ulations. Frequently, however, chronic poor perform-

ers who could be released are not because manage-

ment chooses to sidestep a potentially unpleasant task.

Instead, the decision is made to set these individuals

“on the shelf,” out of the mainstream of activities,

where they can’t cause any problems. Even when this

action is motivated by humanitarian concerns (“I don’t

think he could cope with being terminated”), it often

produces the opposite effect. Actions taken to protect

an unproductive employee from the embarrassment of

termination just substitute the humiliation of being

ignored. Obviously, termination is a drastic action that

should not be taken lightly. However, the conse-

quences for the unproductive individuals and their

coworkers of allowing them to remain after the previ-

ous four actions have proven unsuccessful should be

weighed carefully in considering this option.

This approach to managing ability problems is

reflected in the philosophy of Wendell Parsons, CEO of

Stamp-Rite. He argues that one of the most challenging

aspects of management is helping employees recognize

that job enhancements and advancements are not

always possible. Therefore, he says, “If a long-term

330 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

employee slows down, I try to turn him around by say-

ing how much I value his knowledge and experience,

but pointing out that his production has slipped too

much. If boredom has set in and I can’t offer the

employee a change, I encourage him to face the fact

and consider doing something else with his life”

(Nelton, 1988).

Fostering a Motivating

Work Environment

The second component of employee performance is

motivation. While it is important to see to the training

and the support needs of subordinates and to be

actively involved in the hiring and the job-matching

processes to ensure adequate aptitude, the influence

of a manager’s actions on the day-to-day motivation of

subordinates is equally vital. Effective managers devote

considerable time to gauging and strengthening their

subordinates’ motivation, as reflected in their effort and

concern.

In one of the seminal contributions to management

thought, Douglas McGregor (1960) introduced the term

Theory X to refer to a management style characterized by

close supervision. The basic assumption of this theory is

that people really do not want to work hard or assume

responsibility. Therefore, in order to get the job done,

managers must coerce, intimidate, manipulate, and

closely supervise their employees. In contrast, McGregor

espouses a Theory Y view of workers. He argues workers

basically want to do a good job and assume more respon-

sibility; therefore, management’s role is to assist workers

to reach their potential by productively channeling

their motivation to succeed. Unfortunately, McGregor

believes most managers subscribe to Theory X assump-

tions about workers’ motives.

The alleged prevalence of the Theory X view brings

up an interesting series of questions about motivation.

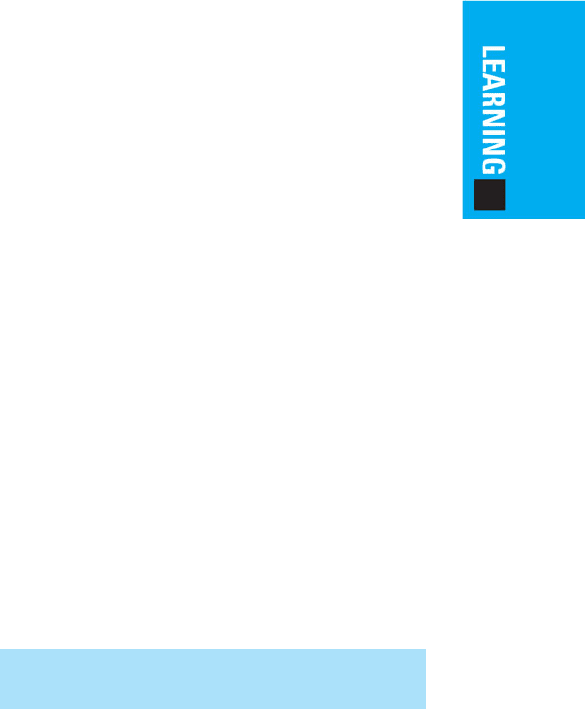

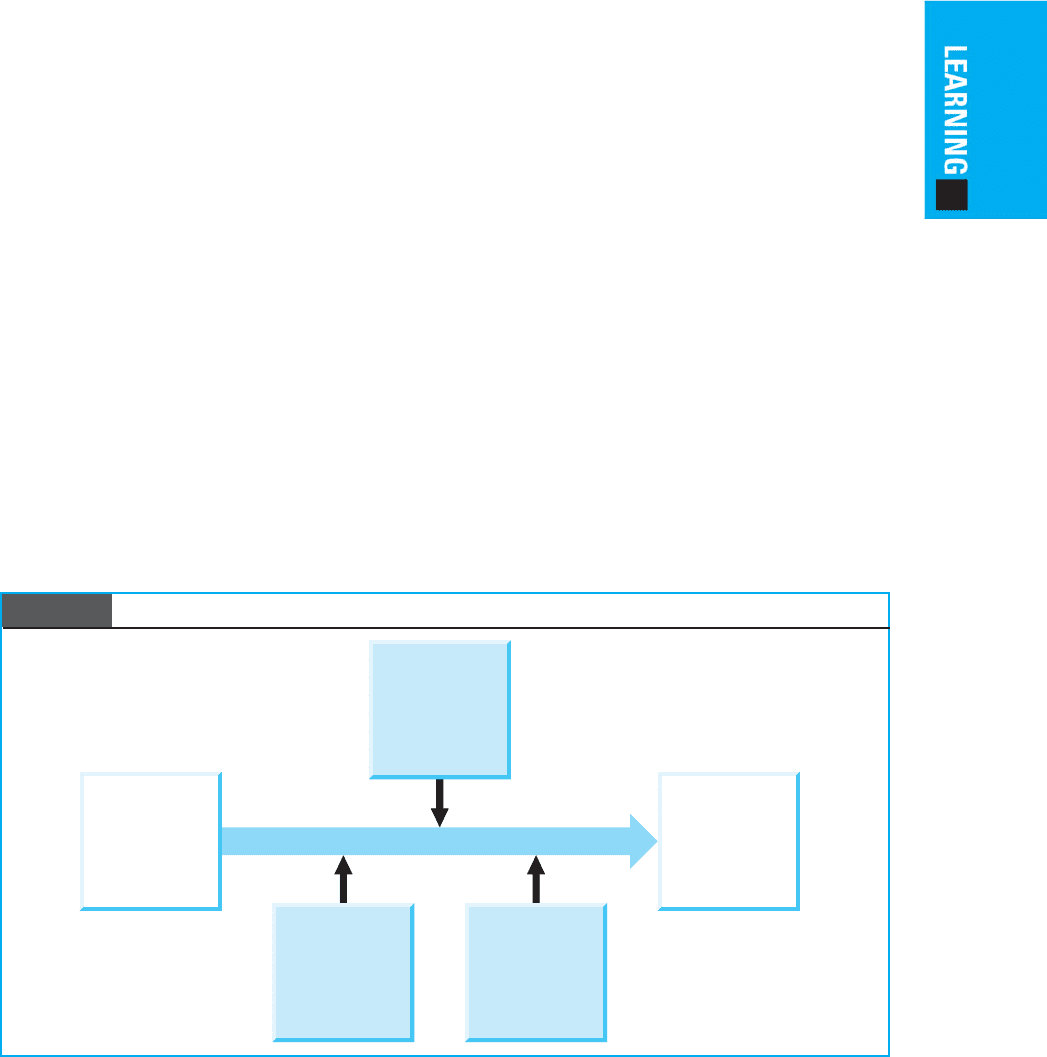

Figure 6.1 Relationship Between Satisfaction and Performance

What is the purpose of teaching motivation skills to

managers? Should managers learn these skills so they

can help employees reach their potential? Or are we

teaching these skills to managers so they can more effec-

tively manipulate their employees’ behavior? These

questions naturally lead to a broader set of issues regard-

ing employee-management relations. Assuming a man-

ager feels responsible for maintaining a given level of

productivity, is it also possible to be concerned about the

needs and desires of employees? In other words, are

concerns about employee morale and company produc-

tivity compatible, or are they mutually exclusive?

Contemporary research, as well as the experience

of highly acclaimed organizational motivation pro-

grams (Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002), supports the

position that concerns about morale and performance

can coexist. As Figure 6.1 shows, effective motiva-

tional programs not only can, but must focus on

increasing both satisfaction and productivity. A high

emphasis on satisfaction with a low emphasis on per-

formance represents an irresponsible view of the role

of management. Managers are hired by owners to look

after the owners’ interests. This entails holding employ-

ees accountable for producing satisfactory results.

Managers who emphasize satisfaction to the exclusion

of performance will be seen as nice people, but their

indulging management style undermines the perfor-

mance of their subordinates.

Bob Knowling, former head of a group of internal

change agents at Ameritech that reported directly to

the CEO, joined US West in February 1996 as vice

president of network operations and technology. His

new job was to lead more than 20,000 employees in a

large-scale change effort to improve service to US

West’s more than 25 million customers.

When asked what the biggest challenge facing

companies is, even successful ones, he responded: “For

me, it begins with changing a culture of entitlement into

EMPHASIS ON PERFORMANCE

EMPHASIS ON

SATISFACTION

High

High

Low

Low

Indulging

Ignoring

Integrating

Imposing

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 331

a culture of accountability. My first week on the job [at

US West], it was immediately apparent that nobody had

been accountable for the reengineering effort. Beyond

that, no one had been accountable for meeting cus-

tomer expectations or for adhering to a cost structure. It

was acceptable to miss budgets. Service was in the tank,

we were overspending our budgets by more than $100

million—yet people weren’t losing their jobs and they

still got all or some of their bonuses. That’s very much

like Ameritech had been. When people failed, we

moved them to human resources or sent them to inter-

national. When I got to US West, I felt like I was walk-

ing into the same bad movie” (Tichy, 1997).

A strong emphasis on performance to the exclusion

of satisfaction is equally ineffective. This time, instead of

indulging, the manager is imposing. In this situation,

managers have little concern for how employees feel

about their jobs. The boss issues orders, and the employ-

ees must follow them. Exploited employees are unhappy

employees, and unhappy employees may seek employ-

ment with the competition. Thus, while exploitation

may increase productivity in the short run, its long-term

effects generally decrease productivity through increased

absenteeism, employee turnover, and in some cases,

even sabotage and violence.

Jim Stuart, who ran several companies before

accepting the position of executive director of the Florida

Aquarium in 1995, reflected on how life’s experiences

convinced him to alter his authoritarian leadership style:

My classmates at Harvard Business School

used to call me the Prussian General: For many

years, that was my approach to leadership.

Then I was hit by a series of personal tragedies

and professional setbacks. My wife died. A

mail-order venture that I had started went

bankrupt. The universe was working hard to

bring a little humility into my life. Rather than

launch another business, I accepted a friend’s

offer to head an aquarium project in Tampa.

I spent the next six years in a job that gave me

no power, no money, and no knowledge. That

situation forced me to draw on a deeper part of

myself. We ended up with a team of people

who were so high-performing that they could

almost walk through walls. Why, I wondered,

was I suddenly able to lead a team that was so

much more resilient and creative than any

team that I had run before? The answer:

Somewhere, amid all of my trials, I had begun

to trust my colleagues as much as I trusted

myself. (McCauley, 1999)

When managers emphasize neither satisfaction

nor performance, they are ignoring their responsibili-

ties and the facts at hand. The resulting neglect reflects

a lack of management. There is no real leadership, in

the sense that employees receive neither priorities nor

direction. Paralyzed between what they consider to be

mutually exclusive options of emphasizing perfor-

mance or satisfaction, managers choose neither. The

resulting neglect, if allowed to continue, may ulti-

mately lead to the failure of the work unit.

The integrating motivation strategy emphasizes

performance and satisfaction equally. Effective man-

agers are able to combine what appear to be competing

forces into integrative, synergistic programs. Instead of

accepting the conventional wisdom that says compet-

ing forces cancel each other out, they capitalize on the

tension between the combined elements to forge new

approaches creatively. However, this does not mean

that both objectives can be fully satisfied in every spe-

cific case. Some trade-offs occur naturally in ongoing

work situations. However, in the long run, both objec-

tives should be given equal consideration.

The integrative view of motivation proposes that

while the importance of employees’ feeling good about

what they are doing and how they are being treated

cannot be downplayed, this concern should not over-

shadow management’s responsibility to hold people

accountable for results. Managers should avoid the

twin traps of working to engender high employee

morale for its own sake or pushing for short-term

results at the expense of long-term commitment. The

best managers have productive people who are also

satisfied with their work environment (Kotter, 1996).

Elements of an Effective

Motivation Program

We now turn to the core of this discussion: a step-by-

step program for creating an integrative, synergistic

motivational program grounded in the belief that

employees can simultaneously be high performers and

personally satisfied. The key assumptions underlying

our framework are summarized in Table 6.1.

It is useful to note the prevailing wisdom among

organizational scholars regarding the relationships

between motivation, satisfaction, and performance

has changed dramatically over the past several

decades. When the authors took their first academic

courses on this subject, they were taught the following

model:

Satisfaction

→

Motivation

→

Performance

332 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

However, over the course of our careers we have

observed the following criticisms of this “contented

cows give more milk” view of employee performance.

First, as researchers began collecting longitudinal

data on the predictors of performance, they discovered

that the satisfaction, motivation, performance causal

logic was wrong. For reasons we will discuss later in

this chapter, it is now believed that:

Motivation

→

Performance

→

Satisfaction

Second, the correlations among these three vari-

ables was very low, suggesting there were a large num-

ber of additional factors that needed to be added to this

basic model. For example, we now know high

performance leads to high satisfaction if workers

believe that their organization reinforces high perfor-

mance by contingently linking it to valued rewards.

(“I want X and I am more likely to get X if I perform

well.”) In other words, performance leads to satisfac-

tion when it is clear rewards are based on perfor-

mance, as compared with seniority or membership.

The addition of this intermediate link between perfor-

mance and rewards (more generally referred to as

outcomes) has so dramatically improved our under-

standing of the organizational dynamics associated

with work performance that it has been incorporated

into a revised model:

Motivation

→

Performance

→

Outcomes

→

Satisfaction

The remainder of this chapter is basically an

account of the improvements that have been made

Table 6.1 Key Assumptions Underlying

Our Framework

1. Employees typically start out motivated. Therefore, a

lack of motivation is a learned response, often fos-

tered by misunderstood or unrealistic expectations.

2. The role of management is to create a supportive,

problem-solving work environment in which facilitation,

not control, is the prevailing value.

3. Rewards should encourage high personal perfor-

mance that is consistent with management objectives.

4. Motivation works best when it is based on self-

governance.

5. Individuals should be treated fairly.

6. Individuals deserve timely, honest feedback on work

performance.

over the past few decades in this basic “four factors”

model of work motivation. We will not only discuss in

more detail the causal logic linking these core vari-

ables, but we will also introduce several additional fac-

tors that we now know must also be included in a

comprehensive motivation program. For example, ear-

lier in this chapter we introduced the notion that

people’s performance is a function of both their moti-

vation and their ability. This suggests we need to add

ability to the basic model as a second factor (besides

motivation) contributing to performance. Each of the

following sections of this chapter introduce additional

variables that, like ability, need to be added to the

basic, four-factor model. Table 6.2 shows the key

building blocks of the complete model, in the form of

six diagnostic questions, organized with reference to

the “four-factor” model of motivation. A model encap-

sulating these questions will be used to summarize our

presentation at the end of the chapter (Figure 6.5), and

a diagnostic tool based on these questions will be

described in the Skill Practice section (Figure 6.7).

ESTABLISH CLEAR

PERFORMANCE EXPECTATIONS

As shown in Table 6.2, the first two elements of our

comprehensive motivational program focus on the

Motivation → Performance link. We begin by focusing

on the manager’s role in establishing clear expectations

and then shift to the manager’s role in enabling mem-

bers of a work group to satisfy those expectations.

It is important to point out we’re not just talking

about hourly employees. Based on data collected since

1993, Right Management Consultants reported that

one-third of all managers who change jobs fail in their

new positions within 18 months (Fisher, 2005).

According to this study, the number-one tip for getting

off to a good start is asking your boss exactly what’s

expected of you and how soon you’re supposed to

deliver it. In fact, there tends to be a negative correla-

tion between the level of one’s position in an organiza-

tion and the likelihood of receiving a job description or

detailed performance expectations. Too often the boss’s

attitude is, “I pay people to know without being told.”

Discussions of goal setting often make reference to

an insightful conversation between Alice in Wonderland

and the Cheshire Cat. When confronted with a choice

among crossing routes, Alice asked the Cat which one

she should choose. In response, the Cat asked Alice

where she was heading. Discovering Alice had no real

destination in mind, the Cat appropriately advised

her any choice would do. It is surprising how often

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 333

supervisors violate the commonsense notion that they

need to make sure individuals under their charge not

only understand which road they should take but what

constitutes an acceptable pace for the journey.

With this parable in mind, managers should begin

assessing the motivational climate of their work envi-

ronment by asking, “Is there agreement on, and accep-

tance of, performance expectations?” The foundation

of an effective motivation program is proper goal set-

ting (Locke & Latham, 2002). Across many studies of

group performance it was shown that the average per-

formance of groups that set goals is significantly higher

than that of groups that didn’t set goals. Goal-setting

theory suggests goals are associated with enhanced per-

formance because they mobilize effort, direct attention,

and encourage persistence and strategy development

(Sue-Chan & Ong, 2002). The salience of goal setting is

so well recognized that it has been incorporated in sev-

eral formal management tools, such as management by

objectives (MBO). Effective goal setting has three criti-

cal components: goal-setting process, goal characteris-

tics, and feedback.

A common theme in this book is, “The way you

do things is very often as important as what you do.”

Applied to the goal-setting process, this means

the manner by which goals are established must be

Table 6.2 Six Elements of an Integrative Motivation Program

MOTIVATION → PERFORMANCE

1. Establish moderately difficult goals that are understood and accepted.

Ask:

“Do subordinates understand and accept my performance expectations?”

2. Remove personal and organizational obstacles to performance.

Ask:

“Do subordinates feel it is possible to achieve this goal or expectation?”

PERFORMANCE → OUTCOMES

3. Use rewards and discipline appropriately to extinguish unacceptable behavior and encourage exceptional performance.

Ask:

“Do subordinates feel that being a high performer is more rewarding than being a low or average performer?”

OUTCOMES → SATISFACTION

4. Provide salient internal and external incentives.

Ask:

“Do subordinates feel the rewards used to encourage high performance are worth the effort?”

5. Distribute rewards equitably.

Ask:

“Do subordinates feel that work-related benefits are being distributed fairly?”

6. Provide timely rewards and specific, accurate, and honest feedback on performance.

Ask:

“Are we getting the most out of our rewards by administering them on a timely basis as part of the feedback

process?”

Ask:

“Do subordinates know where they stand in terms of current performance and long-term opportunities?”

considered carefully. The basic maxim is goals must be

both understood and accepted if they are to be effec-

tive. To that end, research has shown subordinates are

more likely to “buy into” goals if they feel they are part

of the goal-setting process. It has been well docu-

mented that the performance of work groups is higher

when groups choose their goals rather than have them

assigned (Sue-Chan & Ong, 2002).

The motivating potential of chosen goals is espe-

cially important if the work environment is unfavor-

able for goal accomplishment (Latham, Erez, & Locke,

1988). For example, a goal might be inconsistent with

accepted practice, require new skills, or exacerbate

poor management-employee relations. To be sure, if

working conditions are highly conducive to goal

accomplishment, subordinates may be willing to com-

mit themselves to the achievement of goals in whose

formulation they did not participate. However, such

acceptance usually occurs only when management

demonstrates an overall attitude of understanding and

support. When management does not exhibit a sup-

portive attitude, the imposed goals or task assignments

are likely to be viewed as unwelcome demands. As a

result, subordinates will question the premises under-

lying the goals or assignments and will comply only

reluctantly with the demands.

334 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

Sometimes it is difficult to allow for extensive par-

ticipation in the establishment of work goals. For

example, a manager frequently is given directions

regarding new tasks or assignment deadlines that must

be passed on. However, if subordinates believe man-

agement is committed to involving them in all discre-

tionary aspects of the governance of their work unit,

they are more willing to accept top-down directions

regarding the nondiscretionary aspects of work assign-

ments. For example, a computer programming unit

may not have any say about which application pro-

grams are assigned to the group or what priority is

assigned each incoming assignment. However, the

manager can still involve unit members in deciding

how much time to allocate to each assignment (“What

is a realistic goal for completing this task?”) or who

should receive which job assignment (“Which type of

programs would you find challenging?”).

Shifting from process to content, research has

shown that goal characteristics significantly affect

the likelihood that the goal will be accomplished

(Locke & Latham, 2002). Effective goals are specific,

consistent, and appropriately challenging.

Goals that are specific are measurable, unambigu-

ous, and behavioral. Specific goals reduce misunder-

standing about what behaviors will be rewarded.

Admonitions such as “be dependable,” “work hard,”

“take initiative,” or “do your best” are too general and

too difficult to measure and are therefore of limited

motivational value. In contrast, when a new vice presi-

dent of operations was appointed at a major midwestern

steel factory, he targeted three goals: Reduce finished

product rejection by 15 percent (quality); reduce aver-

age shipment period by two days (customer satisfac-

tion); and respond to all employee suggestions within

48 hours (employee involvement).

Goals should also be consistent. An already hard-

working assistant vice president in a large metropolitan

bank complains she cannot increase both the number

of reports she writes in a week and the amount of time

she spends “on the floor,” visiting with employees

and customers. Goals that are inconsistent—in the

sense that they are logically impossible to accomplish

simultaneously—or incompatible—in the sense that they

both require so much effort they can’t be accomplished at

the same time—create frustration and alienation. When

subordinates complain goals are incompatible or inconsis-

tent, managers should be flexible enough to reconsider

their expectations.

One of the most important characteristics of goals is

that they are appropriately challenging (Knight,

Durham, & Locke, 2001). Simply stated, hard goals are

more motivating than easy goals. One explanation for

this is called “achievement motivation” (Atkinson, 1992;

Weiner, 2000). According to this perspective, workers

size up new tasks in terms of their chances for success

and the significance of the anticipated accomplishment.

Based only on perceived likelihood of success, one

would predict that those who seek success would

choose an easy task to perform because the probability

for success is the highest. However, these individuals

also factor into their decisions the significance of com-

pleting the task. To complete a goal anyone can reach is

not rewarding enough for highly motivated individuals.

In order for them to feel successful, they must believe

an accomplishment represents a meaningful achieve-

ment. Given their desire for success and achievement,

it is clear these workers will be most motivated by chal-

lenging, but reachable, goals.

Although there is no single standard of difficulty

that fits all people, it is important to keep in mind high

expectations generally foster high performance and low

expectations decrease performance (Davidson & Eden,

2000). As one experienced manager said, “We get

about what we expect.” Warren Bennis, author of The

Unconscious Conspiracy: Why Leaders Can’t Lead,

agrees. “In a study of schoolteachers, it turned out that

when they held high expectations of their students, that

alone was enough to cause an increase of 25 points in

the students’ IQ scores” (Bennis, 1984, 2003).

In addition to selecting the right type of goal, an

effective goal program must also include feedback.

Feedback provides opportunities for clarifying expecta-

tions, adjusting goal difficulty, and gaining recognition.

Therefore, it is important to provide benchmark oppor-

tunities for individuals to determine how they are

doing. These along-the-way progress reports are partic-

ularly critical when the time required to complete an

assignment or reach a goal is very long. For example,

feedback is very useful for projects such as writing a

large computer program or raising a million dollars for

a local charity. In these cases, feedback should be

linked to accomplishing intermediate stages or com-

pleting specific components.

REMOVE OBSTACLES

TO PERFORMANCE

One of the key ingredients of an effective goal program

is a supportive work environment. After setting goals,

managers should shift their focus to facilitating suc-

cessful accomplishment by focusing on the ability part

of the performance formula. From a diagnostic per-

spective, this can be done by asking, “Do subordinates

MOTIVATING OTHERS CHAPTER 6 335

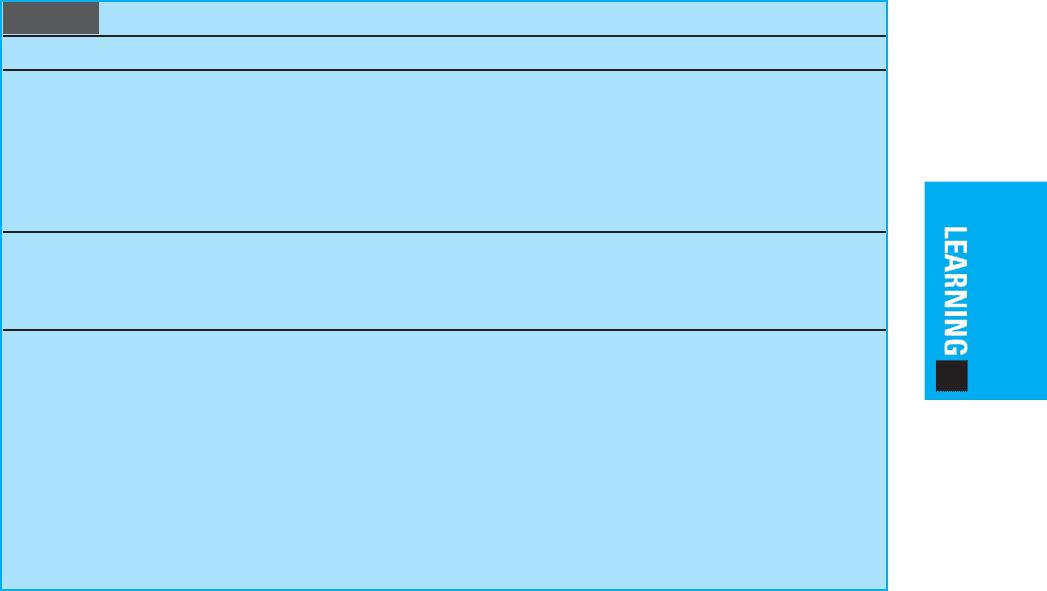

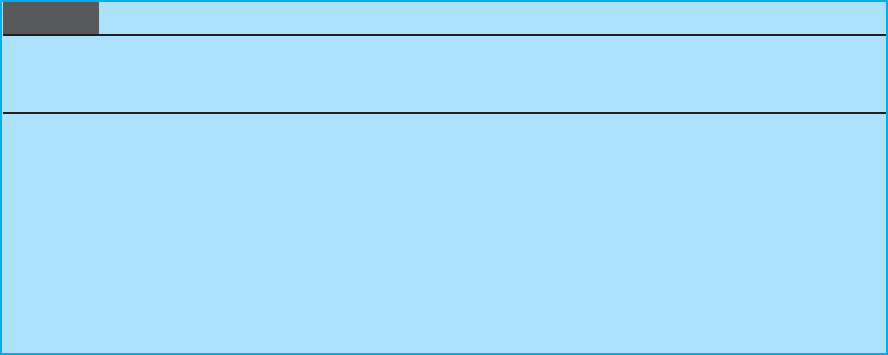

Figure 6.2 Leader Involvement and Subordinate Performance

feel it is possible to achieve this goal?” Help from man-

agement must come in many forms, including making

sure the worker has the aptitude required for the job,

providing the necessary training, securing needed

resources, and encouraging cooperation and support

from other work units. It is the manager’s job to make

the paths leading toward the targeted goals easier for

the subordinate to travel.

This management philosophy can be illustrated

readily with examples from sports. Instead of assuming

the role of the star quarterback who expects the rest of

the team to make him look good, the facilitative man-

ager is more like the blocking fullback or the pulling

guard who specializes in downfield blocking and

punching holes in the opposition’s defenses. In a bas-

ketball example, this type of leader is like the player

who takes more pride in his number of assists than in

the number of points he has scored.

However, as with all general management guide-

lines, effective results follow from sensitive, informed

implementation tailored to specific circumstances. In

this case, the manner in which this enabling, facilitative

role should be implemented varies considerably among

individuals, organizational settings, and tasks. When

subordinates believe strong management support is

needed, leaders who are not aware of the obstacles to

performance, or not assertive enough to remove them,

probably will be perceived as part of the employee’s

problem, rather than the source of solutions. By the

same token, when management intervention is not

needed or expected, managers who are constantly

involved in the details of subordinates’ job performance

will be viewed as meddling and unwilling to trust. This

view of management is incorporated in the “path goal”

theory of leadership (House & Mitchell, 1974; see also,

Schriesheim & Neider, 1996; Shamir, House, & Arthur,

1993), shown in Figure 6.2. The key question it

addresses is, “How much help should a manager pro-

vide?” In response, the model proposes that the level of

involvement should vary according to how much sub-

ordinates need to perform a specific task; how much

they expect, in general; and how much support is avail-

able to them from other organizational sources.

The key task characteristics of the path-goal

model are structure and difficulty. A task that is highly

structured, as reflected in the degree of built-in order

and direction, and relatively easy to perform does not

require extensive management direction. If managers

offer too much advice, they will come across as con-

trolling, bossy, or nagging, because from the nature of

the task itself, it is already clear to the subordinates

what they should do. On the other hand, for an

unstructured and difficult task, management’s direc-

tion and strong involvement in problem-solving activi-

ties will be seen as constructive and satisfying.

The second factor that influences the appropriate

degree of management involvement is the expectations

of the subordinates. Three distinct characteristics influ-

ence expectations: desire for autonomy, experience,

and ability. Individuals who prize their autonomy and

Leader’s

involvement

(How much

help should

I provide?)

Subordinates’

expectations

(How much

help do they

want?)

Task

characteristics

(How much

help is

needed?)

Organizational

structure and

systems

(How much

help is already

available?)

Subordinates’

performance

and

satisfaction

336 CHAPTER 6 MOTIVATING OTHERS

independence prefer managers with a highly participa-

tive leadership style because it gives them more latitude

for controlling what they do. In contrast, people who

prefer the assistance of others in making decisions,

establishing priorities, and solving problems prefer

greater management involvement.

The connection between a worker’s ability and

experience levels and preferred management style is

straightforward. Capable and experienced employees

feel they need less assistance from their managers

because they are adequately trained, know how to

obtain the necessary resources, and can handle polit-

ical entanglements with their counterparts in other

units. They appreciate managers who “give them their

head” but periodically check to see if further assistance

is required. On the other hand, it is frustrating for

relatively new employees, or those with marginal

skills, to feel that their manager has neither the time

nor interest to listen to basic questions.

An important concept in the path-goal approach

to leadership is management involvement should com-

plement, rather than duplicate, organizational sources

of support. Specifically, managers should provide

more “downfield blocking” in situations wherein

work-group norms governing performance are not

clear, organizational rewards for performance are

insufficient, and organizational controls governing

performance are inadequate.

One of the important lessons from this discussion

of the path-goal model is managers must tailor their

management style to specific conditions, such as those

shown in Table 6.3. Although managers should focus

on facilitating task accomplishment, their level of direct

involvement should be calibrated to the nature of the

work and the availability of organizational support, as

well as the ability and experience of the individuals. If

managers are insensitive to these contingencies, they

probably will be perceived by some subordinates as

interfering with their desires to explore their own way,

while others will feel lost.

This conclusion underscores how important it is

that managers understand the needs and expecta-

tions of their subordinates. Bill Dyer, a leading business

consultant, observed that effective managers regu-

larly ask their subordinates three simple questions:

“How is your work going?” “What do you enjoy the

most/least?” “How can I help you succeed?” Asking these

questions communicates a supportive style; hearing

the answers allows managers to fine-tune their facilita-

tive actions.

REINFORCE PERFORMANCE-

ENHANCING BEHAVIOR

Referring back to the basic “four-factor” model of moti-

vation, we now shift our focus from the antecedents of

work performance (the Motivation → Performance link)

to its consequences (the Performance → Outcomes

link). Once clear goals have been established and the

paths to goal completion have been cleared by

management, the next step in an effective motiva-

tional program is to encourage goal accomplishment

by contingently linking performance to extrinsic out-

comes (rewards and discipline) and fostering intrinsic

outcomes. Given our overall emphasis in this book on

improving management skills that are used day in and

day out, the majority of this section will focus on link-

ing performance to extrinsic outcomes.

Table 6.3 Factors Influencing Management Involvement

CONDITIONS APPROPRIATE CONDITIONS APPROPRIATE

FOR

HIGH MANAGEMENT FOR LOW MANAGEMENT

CONTINGENCIES INVOLVEMENT INVOLVEMENT

Task structure Low High

Task mastery Low High

Subordinate’s desire for autonomy Low High

Subordinate’s experience Low High

Subordinate’s ability Low High

Strength of group norms Low High

Effectiveness of organization’s controls and rewards Low High