Wang Q.E. Inventing China Through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

show that, to use Foucault’s words, “the world we know is not this

ultimately simple configuration where events are reduced to accen-

tuate their essential traits, their final meaning, or their initial and

final value. On the contrary, it is a profusion of entangled events.”

28

To acknowledge this “profusion” of multiple pasts in Chinese history

allows these intellectuals to defy the absolute value of Confucian

tradition and construct a new history.

If the “culture fever” movement has as its underlying concern

the reform of tradition, this concern also unites the moderates like

Tang Yijie, Pang Pu, and the radicals like Bao Zunxin and Gan Yang.

While they hold different views in regard to the importance and rel-

evance of Western culture to their project, they all believe that the

purpose of learning from the West is for (re)forming what China had

in the past to meet the needs of the present. This backward-looking

approach to seeking a future in modern China determines that their

project must focus on history. Zhu Weizheng, a history professor of

Fudan University and a noted figure in the “culture fever” move-

ment in Shanghai, stresses that since “traditional culture is a his-

torical existence,” any attempt to understand this culture must be

based on a knowledge of “historical facts” (lishi shishi). To acquire

this knowledge, one needs to employ the method of history. Gaining

this knowledge enables one to discern that traditional culture is a

historical continuum, composed of two parts; one is known as the

“dead culture” (si wenhua) whereas the other as the “living culture”

(huo wenhua). Nevertheless, a “dead culture” is not necessarily

undesirable and a “living culture” is not always desirable. Rather,

provided with historical knowledge, people can reverse the nature

of these two to meet their needs and develop a more viable, useful

tradition.

29

Thus, seeking a new tradition is always in juxtaposition with

the attempt at writing a new history. In so doing, historians and

intellectuals challenge their given past embodied in the form of

tradition, and change it in order to make it more harmonious with

the changing social milieu. The way in which modern historians

summon the past for the present leads to the creation of not only a

new form of historiography, but history in its philosophical sense,

as argued by Benedetto Croce. “What constitutes history,” claimed

Croce, “may be thus described: it is the act of comprehending and

understanding induced by the requirements of practical life.” In

other words, every true history is contemporary history; it is pro-

duced to correspond to the present need.

30

In its production, histo-

rians dismantle the image of an accepted past and construct a new

one with a new perspective and a new method. “History thus trans-

208 EPILOGUE

formed,” says David Lowenthal, “becomes larger than life, merging

intention with performance, ideal with actuality.”

31

I hope this book

is a contribution to our knowledge of the significant transformation

in both Chinese history and historical writing of the twentieth

century.

EPILOGUE 209

G

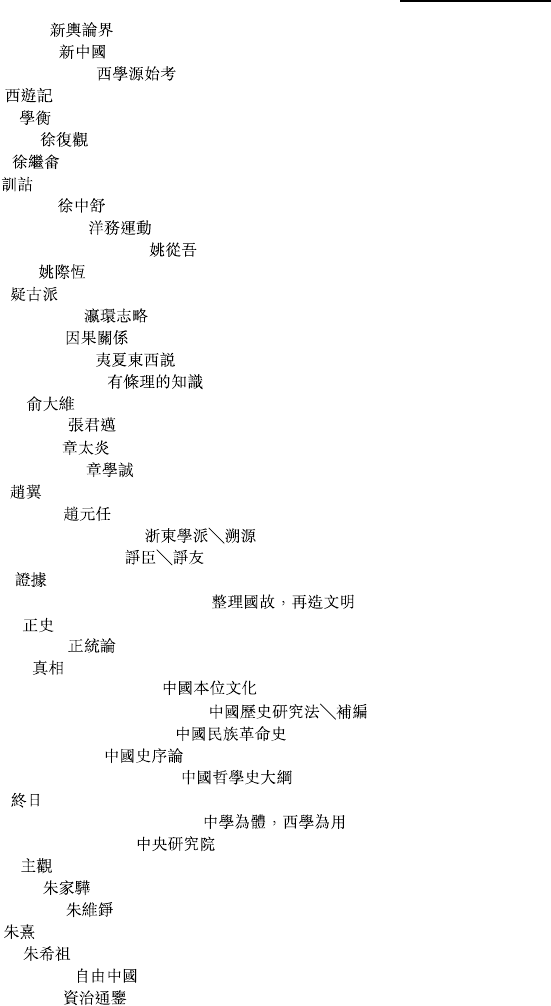

lossary

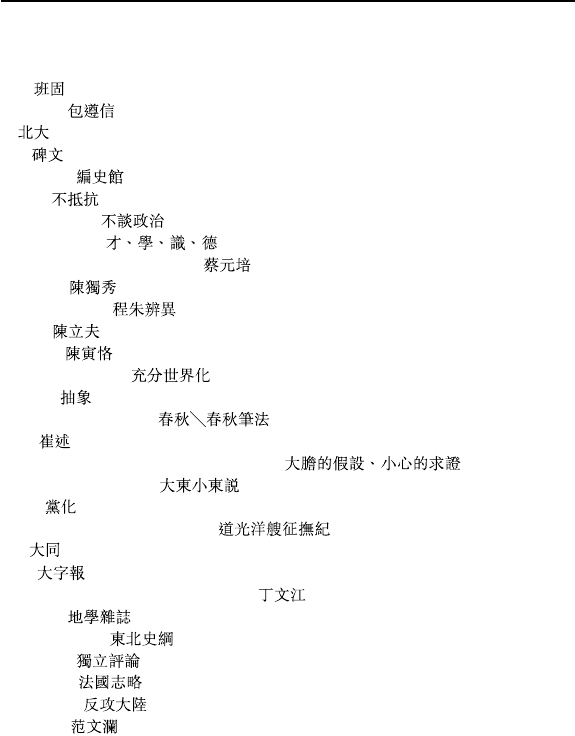

Ban Gu

Bao Zunxin

Beida

Beiwen

Bianshiguan

Budikang

Butan zhengzhi

Cai, xue, shi, de

Cai Yuanpei (Tsai Yuen-pei)

Chen Duxiu

Chengzhu bianyi

Chen Lifu

Chen Yinke

Chongfen shijiehua

Chouxiang

Chunqiu/Chunqiu bifa

Cui Shu

Dadan de jiashe, xiaoxin de qiuzheng

Dadong xiaodong shuo

Danghua

Daoguang yangsou zhengfu ji

Datong

Dazibao

Ding Wenjiang (Ting Wen-ch’iang)

Dixue zazhi

Dongbei shigang

Duli pinglun

Faguo zhilue

Fangong dalu

Fan Wenlan

211

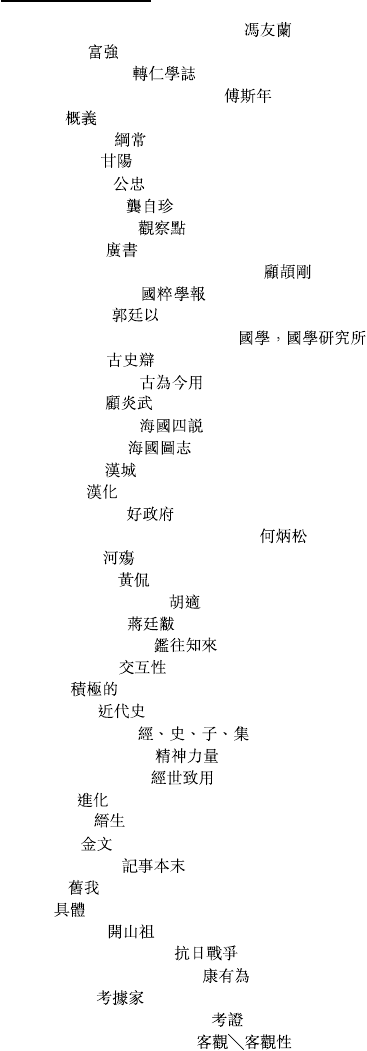

Feng Youlan (Feng Yu-lan)

Fuqiang

Furen xuezhi

Fu Sinian (Fu Ssu-nien)

Gaiyi

Gangchang

Gan Yang

Gongzhong

Gong Zizhen

Guancha dian

Guangshu

Gu Jiegang (Ku Ch’ieh-kang)

Guocui xuebao

Guo Tingyi

Guoxue, guoxue yanjiusuo

Gushibian

Guwei jinyong

Gu Yanwu

Haiguo sishuo

Haiguo tuzhi

Hancheng

Hanhua

Hao zhengfu

He Bingsong (Ho Ping-sung)

He Shang

Huang Kan

Hu Shi (Hu Shih)

Jiang Tingfu

Jianwang zhilai

Jiaohu xing

Jiji de

Jindaishi

Jing, shi, zi, ji

Jingshen liliang

Jingshi zhiyong

Jinhua

Jinsheng

Jinwen

Jishi benmo

Jiuwo

Juti

Kaishanzu

Kangri zhanzheng

Kang Youwei (Yu-wei)

Kaoju jia

Kaozheng (Kao-ch’eng)

Keguan/Keguan xing

212 GLOSSARY

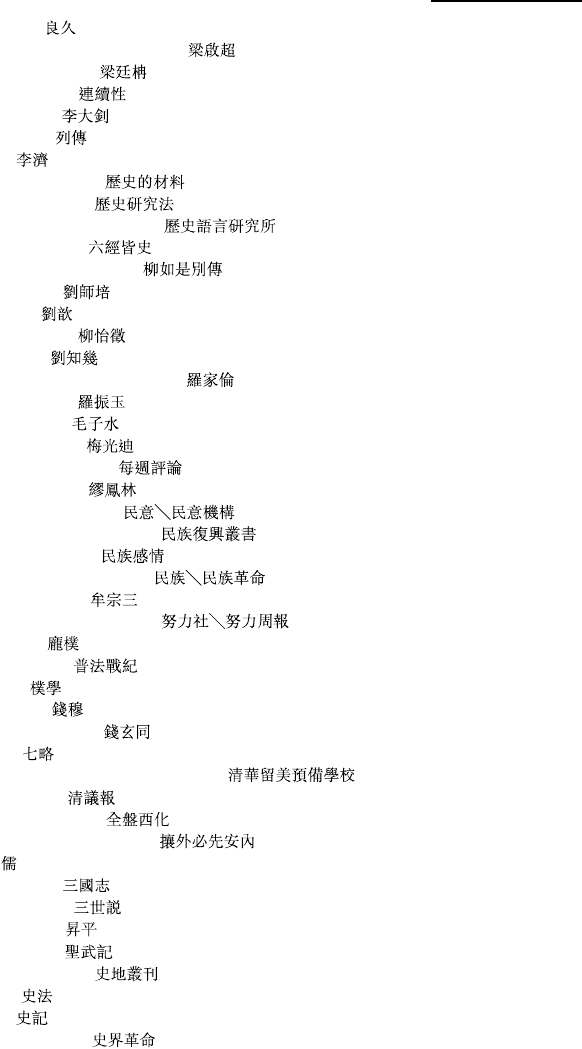

Liangjiu

Liang Qichao (Ch’i-ch’ao)

Liang Tingnan

Lianxu xing

Li Dazhao

Liezhuan

Li Ji

Lishi de cailiao

Lishi yanjiufa

Lishi yuyan yanjiusuo

Liujing jieshi

Liu Rushi biezhuan

Liu Shipei

Liu Xin

Liu Yizheng

Liu Zhiji

Luo Jialun (Lo Chia-lun)

Luo Zhenyu

Mao Zishui

Mei Guangdi

Meizhou pinglun

Miao Fenglin

Minyi/minyi jigou

Minzu fuxing congshu

Minzu ganqing

Minzu/minzu geming

Mou Zongsan

Nuli she/nuli zhoubao

Pang Pu

Pufa zhanji

Puxue

Qian Mu

Qian Xuantong

Qilue

Qinghua liumei yubei xuexiao

Qingyi bao

Quanpan xihua

Rangwai bixian annei

Ru

Sanguozhi

Sanshishuo

Shengping

Shengwuji

Shidi congkan

Shifa

Shiji

Shijie geming

GLOSSARY 213

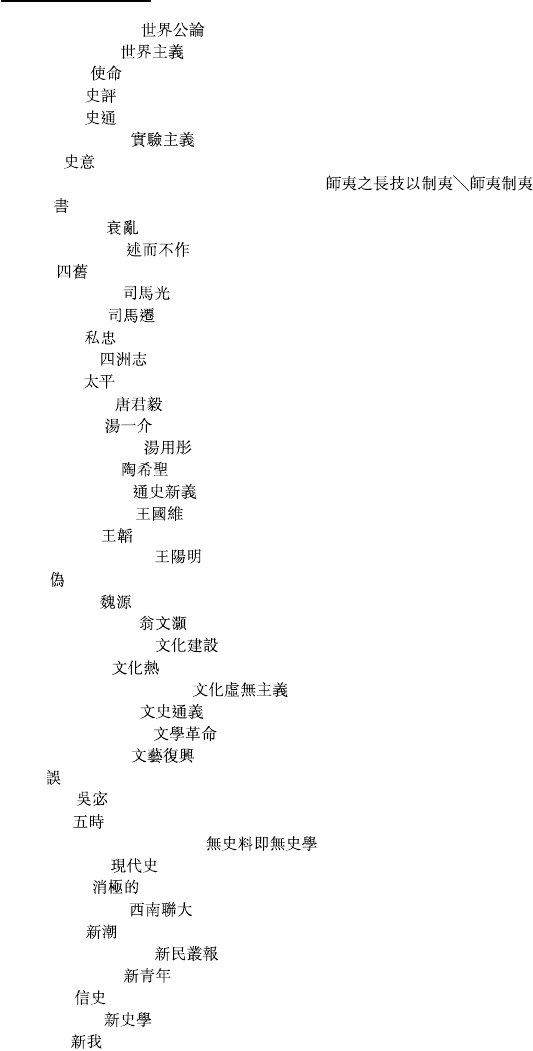

Shijie gonglun

Shijie zhuyi

Shiming

Shiping

Shitong

Shiyan zhuyi

Shiyi

Shiyi zhi changji yi zhiyi/Shiyi zhiyi

Shu

Shuailuan

Shuer buzuo

Sijiu

Sima Guang

Sima Qian

Sizhong

Sizhouzhi

Taiping

Tang Junyi

Tang Yijie

Tang Yongtong

Tao Xisheng

Tongshi xinyi

Wang Guowei

Wang Tao

Wang Yangming

Wei

Wei Yuan

Weng Wenhao

Wenhua jianshe

Wenhua re

Wenhua xuwu zhuyi

Wenshi tongyi

Wenxue geming

Wenyi fuxing

Wu

Wu Mi

Wushi

Wushiliao jiwu shixue

Xiandaishi

Xiaoji de

Xinan lianda

Xinchao

Xinmin congbao

Xinqingnian

Xinshi

Xinshixue

Xinwo

214 GLOSSARY

Xin yulunjie

Xin zhongguo

Xixue yuanshikao

Xiyouji

Xueheng

Xu Fuguan

Xu Jiyu

Xungu

Xu Zhongshu

Yangwu yundong

Yao Congwu (Tsung-wu)

Yao Jiheng

Yigupai

Yinghuan zhilue

Yinguo guanxi

Yixia dongxi shuo

You tiaoli de zhishi

Yu Dawei

Zhang Junmai

Zhang Taiyan

Zhang Xuecheng

Zhao Yi

Zhao Yuanren

Zhedong xuepai/suyuan

Zhengchen/Zhengyou

Zhengju

Zhengli guogu, Zaizao wenming

Zhengshi

Zhengtong lun

Zhenxiang

Zhongguo benwei wenhua

Zhongguo lishi yanjiufa/bubian

Zhongguo minzu gemingshi

Zhongguoshi xulun

Zhongguo zhexueshi dagang

Zhongri

Zhongxue weiti, xixue weiyong

Zhongyang yanjiuyuan

Zhuguan

Zhu Jiahua

Zhu Weizheng

Zhu Xi

Zhu Xizu

Ziyou zhongguo

Zizhi tongjian

GLOSSARY 215

N

otes

Chapter One

1. Cf. Robert E. Frykenberg, History and Belief: The Foundation of

Historical Understanding (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publish-

ing Co., 1996).

2. Gordon Graham, The Shape of the Past: A Philosophical Approach to

History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 2.

3. Ibid.

4. Although most Chinese scholars pronounce his name Chen Yinque, it

seems Chen himself used “Yinke,” or its Wade-Giles version “Yin-ko,” over-

seas, both in the 1920s and in the 1940s. In a letter to Fu Sinian while he

was in Oxford after World War II, Chen asked Fu to write him back, using

the name “Chen Yin-ke.” See “Fu Sinian dangan” (Fu Sinian’s archive),

I–709, Fu Sinian Library, Institute of History and Philology, Academia

Sinica, Taiwan. Zhao Yuanren, an acclaimed Chinese linguist and Chen’s

friend and colleague, also said that one should pronounce “Yinke” rather

than “Yinque.” See Zhao and Yang Buwei’s “Yi Yinke” (Chen Yinke remem-

bered), in Yu Dawei et al. Tan Chen Yinke (About Chen Yinke) (Taipei:

Zhuanji wenxue chubanshe, 1970), 26.

5. Prasenjit Duara, Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning

Narratives of Modern China (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1993),

4.

6. See Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds. The Invention of

Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983) and Jocelyn

Linnekin, “Defining Tradition: Variations on the Hawaiian Identity,”

American Ethnologist, 10 (1983), 241–252.

217