Tsutsui W.M. A Companion to japanese histоry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

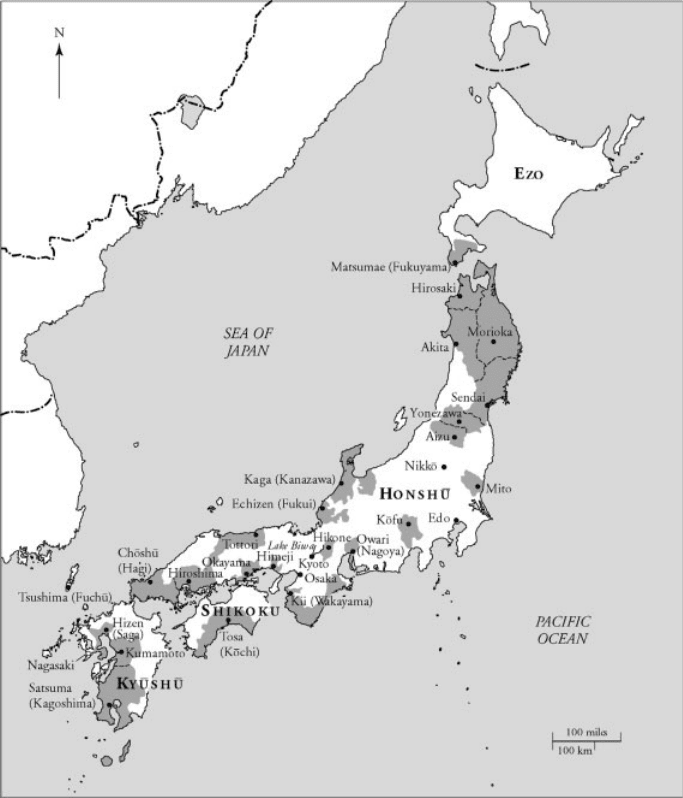

Map 2 Major domains, castle towns, and cities of Tokugawa Japan

CHAPTER FOUR

Unification, Consolidation,

and Tokugawa Rule

Philip C. Brown

A major trend in recent scholarship on early modern Japanese politics has been to play

the role of the little boy in the crowd who shouted out, ‘‘The emperor has no

clothes!’’ In this case, the issue is not the emperor (whom most have generally treated

as unimpressively endowed with actual vestments of power), but the sho

¯

gun and his

attendant authority. The chorus of critical voices is not uniformly harmonious, and

there are still defenders of older images of shogunal authority, but the trend is

unmistakable. In the case of the starkly honest little boy in the fa ble, the result was

simply to reveal the foolishness of both adult behavior and imperial pretense; the

emerging picture of early modern governance and politics is one of considerably

greater complexity than such conclusions, however, and not beyond debate. While

moving beyond stereotypes of premodern society that dominated images through the

mid twentieth century, and while displaying the inf luence of current trends in

Western historiography, the new image of early modern Japan also exhibits some

rather remarkable lacunae. Scholars have focused more of their attention on devel-

opments at the regional and local level – daimyo

¯

domains, cities, towns, and villages –

even though we still have significant gaps in our understanding of elite developments,

including the shogunate.

1

Simply put, a limited number of workers in the field

translates into less comprehensiv e study than is ideal.

Periodization is fundamental to historical study, but often not directly addressed. It is a

slippery subject, made hard to grasp because any scheme is dependent on what subject an

author places at the center of her attention. An art historian’s periodization will differ

from that offered by an economic historian; a demographic historian will note different

dividing lines than a student of religion. This essay adopts a political framework for

periodization. Broadly speaking, it concerns competition over who has the right to

exercise administrative powers and the actual exercise of that authority, including the

activities of popular groups to influence policy. Much of the discussion treats the

development of political institutions, those formal and informal (that is, customary)

structures people create through individual and collective efforts that shape the way in

which political authority is exercised and defined as legitimate or illegitimate.

‘‘Early modern’’ is adopted as a moniker primarily out of convenience; it is the most

widely used designation for the period encompassed here. To the degree there are

continuities with the ‘‘modern’’ Meiji political and institutional order, those links lie

A Companion to Japanese History

Edited by William M. Tsutsui

Copyright © 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

largely in the realm of general attitudes toward authority, government officials, and

(semi-)bureaucratic order.

2

The Meiji institutional structure at all levels varied signifi-

cantly from its predecessor states of the late fifteenth to nineteenth centuries. There is

sufficient continuity in political-institutional developments from the late fifteenth to

mid nineteenth century, however, to give this period a sense of conceptual integrity.

A Brief Overview of Political Development during the Era

Unlike the rise of new overlords in China or England in which one leading family

replaced another in a coup d’e

´

tat or after a short period of civil war, the rise of

Tokugawa pre-eminence capped a century of vir tually continuous civil wars in

Japan from the late fifteenth to late sixteenth centuries. The upshot of the O

¯

nin

War (1467) was fragmentation and devolution of real ruling authority to several

hundred territorially limited warlords (sengoku or warring states daimyo

¯

) who fought

ceaselessly with each other. That process prov ed to be highly creative and whatever

the cost in blood and treasure, it ultimately created the foundation for the Pax

Tokugawa (1600–1867). In broad outline, daimyo

¯

(baronial overlords) who survived

focused on consolidating power within their domains, increased their direct military

power relative to that of enfeoffed retainers, expanded their tax base through invest-

ments in expanding arable lands, constructed riparian works to limit flood damage,

and exte nded irrigation works, in addition to demonstrating good political sense and

superb generalship. Although ultimately a number of large daimyo

¯

re-emerged to

take positions of regional or national leadership, relatively small domains of sub-

provincial size remained typical until after the Meiji Restoration.

Despite the presence of some 260 daimyo

¯

who acted with a high degree of

autonomy throughout the era, the new, more stable daimyo

¯

domains formed the

building blocks for two and a half centuries of peace. Coalitions of such daimyo

¯

began

to emerge in the mid sixteenth century, increasing the scale of battles to tens and

hundreds of thousands of soldiers by 1600.

3

While famous warlords Takeda Shingen

(1521–73), Dat e Masamune (1566–1636), Uesugi Kenshin (1530–78), and others

failed to achieve nationwide dominance, the ambitions of Oda Nobunaga (1534–82)

and his able general Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–98) led to administrative arrange-

ments and controls that finally enabled former Oda ally Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–

1616) to establish a remarkably peacefu l reign beginning in 1600 with his victory at

Sekigahara. (Foreign threats were minimal, and the last serious disturbance associated

with foreign powers was dispatched in 1637 with the suppression of the Shimabara

Rebellion in which the Portuguese were implicated.)

The Tokugawa sho

¯

guns formally exercised political leadership as the representative

of the emperor, but there was no nationwide system of taxation, justice, or military.

First and foremost the sho

¯

gun was primus inter pares, the largest of daimyo

¯

(in direct

control of about one-eighth of the land). As leader of the victorious coalition

of daimyo

¯

, Ieyasu’s prestige and status was clearly head and shoulders above the

other daimyo

¯

. By manipulating status symbols, pledges of allegiance, the allocation of

domain lands, and certain aspects of daimyo

¯

personal behavior (for example, political

intermarriage and adoption with key daimyo

¯

families), the Tokugawa built an endur-

ing political network with the daimyo

¯

. Although seventeenth-century disturbances

70 PHILIP C. BROWN

among daimyo

¯

retainers (oie so

¯

do

¯

) reflected significant dissatisfaction, daimyo

¯

stakes in

the emerging order were sufficiently great relative to the costs and risks of taking on

the sho

¯

gun, and with him, perhaps much of Japan, that they all chose continued,

peaceful coexistence under the Tokugawa umbrella.

While administrative powers were limited and never resulted in the establishment

of a nationwide, centrally administered bureaucratic government, the prestige and

authority of the sho

¯

gun had very real political and administrative consequences. Oda

Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and the Tokugawa sho

¯

guns could compel military

service from daimyo

¯

(broadly defined to include items like the rebuilding of shogunal

fortifications such as Osaka Castle) and to that end they successfull y demanded that

daimyo

¯

provide estimates of domain value, but they could not compel the imple-

mentation of a specific standard on which that value was calculated.

4

The sho

¯

gun

provided – increasingly – a venue in which diversity issues could be resolved. Through

suasion as well as formal court procedures, domains turned to the sho

¯

gun to settle

border disputes among them, complaints against agents in other territories (including

Tokugawa lands), and so on. Later, shogunal officials were active in dealing with

popular disturbances that crossed domain boundaries or undertaking regional ripar-

ian efforts that likewise transcended the authority of one domain. While weak relative

to modern states, this arrangement had sufficient bonds to sustain a stable relation-

ship among daimyo

¯

until the mid nineteenth century.

Peace paid extraordinary dividends for Japan. Whether one accepts a figure of 12

million or 18 million souls in 1600, the expansion to some 24 millions by the early

eighteenth century, ultimately plateauing at 28 to 30 millions by the early nineteenth

century, was extraordinary for a premodern society.

5

Population growth both

depended upon and stimulated economic growth (primarily agriculture) and diversi-

fication, interregional trade, and regional economic specialization. (While there was

historically significant international trade, it was not large enoug h or sufficiently

oriented toward mass consumption goods to make much of a contribution to the

expanding economy.)

Urbanization was first dominant in the shogunal headquarters of Edo and daimyo

¯

castle towns like Kanazawa or Ko

¯

chi that served as domain administrative centers, but

later focused on market-oriented towns, and expanded the ranks of the middle

classes. Increased trade stimulated the growth of industrial and commercially oriented

social strata in the villages too. These groups increasingly participated in a burgeoning

national cultural efflorescence identified with the Genroku era (1688–1703) as well as

creating political pressures and prob lems.

By the late seventeenth and early eightee nth centuries the key political issues of the

day had shifted from establishing and reinforcing the foundations of a stable polity to

issues of resource allocation. Riparian works, urban construction (and reconstruction

made necessary by frequent fires and earthquakes), the expansion of arable to its

extreme limits given contemporary technological constraints, and similar develop-

ments associated with population growth, depleted forest resources, destabilized

watersheds, and even exhausted some marine resources. Merchants and parvenu

groups in rural areas aroused envy even where their activities did not create suspicion

of unfair trading practices and hostility. Daimyo

¯

and samurai found themselves

strapped. Unable to effectively raise taxes to meet growing expenditures and inflation,

daimyo

¯

budgets were a sea of red ink. Daimyo

¯

resorted to cost-cutting by reducing

UNIFICATION, CONSOLIDATION, AND TOKUGAWA RULE 71

the salaries paid their samurai and forced loans from well-off merchants and farmers.

For samurai, such daimyo

¯

-imposed sacrifices came on top of the significantly declin-

ing purchasing power of their incomes.

As the eighteenth century ended and the nineteenth began, two major famines and

increased popular protests, a number violent, punctuated an emergent sense of

malaise. Administrative reforms failed to solve both domain and social problems.

Many a commoner and samurai alike felt that proper social order had been turned

upside down. Into this environment came increased efforts of Westerners – Russians,

British, American – to increase Japanese intercourse with the world. A combination of

early seventeenth-century Japanese hostility and a lack of widespread European

interest in trade with Japan had resulted in seventeenth-century decline in, and

restriction of, foreign contacts. Trade with the Dutch was limited to Nagasaki;

Chinese trade was also centered there but was carried out through contacts with

the Ryu

¯

kyu

¯

Islands as well. Contacts with Korea were conducted through the island

daimyo

¯

of Tsushima (the So

¯

), initially for the purpose of using diplomatic relations to

enhance seventeenth-century shogunal legitimacy, but also for the economic benefits

trade brought the daimyo

¯

. Porous borders in northern Japan per mitted a trade with

Japan that expanded in importance for Japanese and Ainu throughout the era.

While the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637 occurred in a context in which Japan was

the technological equal of the West and daim yo

¯

reaction to the threat largely uniform,

nineteenth-century Western efforts to engage Japan took place in a less advantageous

technological and domestic political context. Shogunal officials, more than many

daimyo

¯

, were alert to the changing technologi cal balance between Japan and the

West; when Perry arrived in 1853 and 1854, they pursued a pragmatic course and

engaged Western nations. Many daimyo

¯

, however, reached different conclusi ons

about Western military power and sought to sustain the policy of rejecting Western

entreaties that had hardened since the late eighteenth century. In an environment of

widely sensed malaise and distrust, the division of opinion and the setting of a new

course for resolving mounting domestic problems were ultimately resolved only with

the conclusion of the civil war (the Boshin War, 1868–9) that ushered in Japan’s first

modern government.

Breaking Away from Meiji

Within the broad-brush image just sketched, Wester n scholars have come to recog-

nize significant positive elements in Japan’s early modern, although considerable

room for debate remains. This was not always the case. Up through the mid

twentieth century, the predominant image of early modern Japan and the pre ceding

Sengoku era was negative. It was characterized as feudal, and the late fifteenth to late

sixteenth century especially was seen as something of a Dark Age, filled with disorder

and war (in cinema, it serves as the stage for a Japanese equivalent of the Western

shoot-’em-up, the chambara films of samurai valor). That judgment and a similarly

negative image of the Tokugawa owed much to the self-justification of victorious

parties in the Meiji Restorat ion. To legitimate their capture of political power they

painted their immediate Tokugawa predecessors as backward and inept. The critical

tone was supported by a small army of people like Fukuzawa Yukichi who were

72 PHILIP C. BROWN

ardent supporters of varying degrees of reform along Western lines, the pursuit of

‘‘Western Science to preserve Eastern Ethics’’ (wakon yo

¯

sai), the creation of a Japan

characterized by ‘‘Civilization and Enlightenment’’ (bunmei kaika) grounded in a

‘‘Rich Country, Strong Army’’ (fuk oku kyo

¯

hei) capable of preserving Japan’s inde-

pendence and ability to act in the late nineteenth-century world of imperialist state

relations.

English-language scholarship, too, tended toward this characterizations, but be-

ginning with the 1968 publication of John Whitney Hall and Marius Jansen’s essay

collection, Studies in the Institutional H istory of Early Modern Japan, a concerted

effort arose to recast Tokugawa (and later, the age preceding it) in a more positive

light. The title embodied the effort to throw off the image of feudal society and to

highlight the era’s positive contributions to the creation of post-Restoration, mod ern

Japan. This approach accompanied the extensive effort to recast late nineteenth- and

early twentie th-century Japanese history as a generally positive and successful effort at

‘‘modernization,’’ a view that was embodied in the Princeton University Press series,

‘‘Studies in the Modernization of Japan,’’ Thomas C. Smith’s The Agrarian Origins

of Modern Japan, and other works.

6

This liberation of the Tokugawa image from the critical gaze of early Meiji Japan

had its own limitations, however; in its own way it made the Tokugawa prisoner to

Meiji, encouraging work that looked for positive links between the two eras. The

harsh side of Tokugawa life and politics got considerably short shrift. Together with

the reconsideration of America’s international role during the Vietnam War, Marxist

and ‘‘progressive’’ historians not only launched intellectual broadsides at the mod-

ernizationist post-Meiji studies, but also at images of Tokugawa Japan implicated in

that paradigm. Work appeared on dissenting voices in Japanese history

7

and peasant

rebellion.

8

Since that time, several studies have transcended the Meiji Restoration in a

further effort to break the constraints of earlier efforts to portray Tokugawa–Meiji

links as largely positive, but at the same time present a balanced assessment of the

transition.

9

Both of these broad efforts to break the chains of Meiji must be evaluated in

generally positive terms, for they open the possibility of taking the history of the

sixteenth to mid nineteenth century much more on its own terms than had been the

case previously. The best of recent scholarship on the early modern polity of Japan

does precisely that, at least within the bounds of what any historian can do. Without

this effort, much of what is described below would not have been possible.

Expanding Interests

Early work on the early modern stat e and politics devoted substantial attention to the

development of shogunal and domain rule. While early studies paid some attention to

regional developments, the general thrust was to stress the development of a single

pattern of administration, one in which daimyo

¯

were clearly in conformity with the

emergent national leaders hip.

10

Recent studies, even of the formative stages of the

shogunate offer an alternative to images of extensive hegemonic power.

11

Mark

Ravina and Luke Roberts have stressed domain autonomy almost to the point of

independence from the sho

¯

gun.

12

UNIFICATION, CONSOLIDATION, AND TOKUGAWA RULE 73

The issues generated by such studies are not limited to re-examination of the balance of

power between the Tokugawa sho

¯

guns and their immediate predecessors (Oda Nobu-

naga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi) on the one hand, and the daimyo

¯

they led on the other;

they also provide us with a sense of the diversity of domain administrative structure and

the policies as they evolved within domains throughout the era. Ravina presents clear

evidence of wavering policy even over such a fundamental issue as the urbanization of

samurai (part of the effort to separate warriors from villagers) in Hirosaki domain in the

eighteenth century, Brown does so for sixteenth- and seventeenth-century tax structures

in Kaga, as does Roberts for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Tosa economic policy.

13

Within domains a parallel development can be seen as scholars like James McClain

explored the degree to which castle town growth could be controlled by daimyo

¯

.

14

The locus of change scholars identify has shifted toward the motivations, incen-

tives, and issues important to daimyo

¯

, retainers, townsmen, and villagers. Actors at

these levels are now likely to be described as performing with considerable autonomy,

and such common directions in policy or the outlines of administrative structure as

are still recognized are likely to be explained as the result of a limited array of potential

solutions to widespread administrative challenges. Rather than separating warrior

from peasant as the result of Hideyoshi’s Sword Hunt (1588) and class separation

edicts (1591), daimyo

¯

are seen as developing a combination of policies over a number

of decades that increasingly restricted the number of landholding, rustic samurai and

their autonomy to control subordinate villagers.

15

Current scholarship even acknow-

ledges a lesser degree of class separation, though all scholars still treat early modern

society as highly stratified and status-conscious. Popular political action ( ikki) has also

drawn recent attention. In addition to Herbert Bix and Stephen Vlastos, case studies

were published by William Kelly, Selcuk Esenbel, and Anne Walthall. The most

comprehensive treatment, however, has been the political scientist James White’s

Ikki: Social Conflict and Political Protest in Early Modern Japan.

16

A corollary to increased focus on a wider array of historical actors has been a

breakdown of stereotyped images of who participated meaningfully in political activ-

ity. While studies of popular protests have particularly dramatic appeal, the most

significant evidence comes from those studies that show commoner participation in

domain policy formation and the ability of women to act dramatically in both village

and national affairs in more ordinary contexts.

17

Extension of scholarly interest into

relatively lower levels of society has meant something of a reconceptualization of

‘‘Japan.’’ Studies by David How ell, Brett Walker, and Gregory Smits have encom-

passed Japanese northern and southern borderlands (Hokkaido

¯

and Okinawa) and

the political-economic relations between Japanese and local populations.

18

In add-

ition to undermining the image of Japanese isolationism and exploring the subor-

dination of these territories to Japanese overlordship, these authors open the issue of

Japanese self-identity. Marcia Yonemoto also takes up the issue of identity and

provides useful insights into an emerging sense of domestic co nnections, at least

among the intellectual and ruling elites, despite the awareness of domestic differ-

ence.

19

The images she paints of a Japan comprised of provinces as opposed to

daimyo

¯

domains reveals the expanding proto-national sensitivity that coexisted with

strong local domain identities. (The downside of this growing national awareness was

development of a stream of thinking that stressed Japan’s uniqueness and that was

sometimes manifested as blatant anti-foreignism.)

20

74 PHILIP C. BROWN

The broadening of scholarly interests extends to consideration of human inter-

action with the environment. The political dimensions of such interaction are most

clearly seen in the work of Conrad Totman

21

but have also been manifested in

Walker’s work, among others. In this context, part of the mid-Tokugawa crisis of

resource allocation encompassed solving significant ecological problems associated

with exhaustion of forest resources (given the levels of technological development at

the time).

The Question of Political Early Modernity

Totally apart from the links of Tokugawa Japan to its Meiji successor state, the de-

emphasis on the role of a strong political center as a motive force in political history

creates an image of the early modern polity that is closer to the more decentralized

medieval ruling structure of Ashikaga Japan. Jeroen Lamers’s treatment of Oda

Nobunaga makes him more of a force in Japan’s transition to stability than simply a

precursor to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, but the tools Oda employed have an essential

continuity with those of Hideyoshi and his successors in their emphasis on controlling

the person of subordinate daimyo

¯

more than subordinating them in an integrated

national administration.

22

Pledges of loyalty, hostage-holding, and visits to a hege-

mon’s capital, even after they become routinized playscripts in the mid seventeenth

century, are fundamentally the cement of a premodern order and gave life to early

characterizations of the Tokugawa period as feudal. Recent studies show similar

processes at work within domains through at least the mid seventeenth century.

If the growth of centralized political and administrative power, accompanied by the

bureaucratic routinization of administration are taken as hallmarks of political early

modernity (as Hall did in Government and Local Power in Japan), then these occur

most clearly within domain administrations (including the house administrative

organs of the Tokugawa). Fiefs of subordinate retainers became virtual fictions;

even where they remained in form, they were largely gutted of content: typically,

enfeoffed retainers could not set their own taxes, compel commoners to serve

them, administer justice or undertake many other basic administrative tasks at all.

Where such functions remained, retainer autonomy was almost completely restricted

by domain ordinance. Daimyo

¯

administrative apparatus connected directly to the self-

governing institutions of villages, towns, temples, shrines, and even outcaste (hinin)

communities.

Although less complete at the national level, central authority under Nobunaga,

Hideyoshi, Ieyasu, and their successors clearly grew. While based on pledges of loyalty

and other medieval techniques, these overlords possessed and used their ability to

confirm daimyo

¯

overlordship of dom ains to post them to new lands or to remove

them from power. With the major exception of defeat in battles like Sekigahara

(1600), Osaka (1614–15), and Shimabara when large enemy daimyo

¯

might be

destroyed or reduced in size, the daimyo

¯

whose domains were reduced, eliminated,

or moved were overwhelmingly small and mid-sized, not the large province or multi-

province holding lords. Hideyoshi was able to order invasions of Korea in pursuit of

subduing China. A semi-bureaucratic structure was established for maintaining con-

trol over national networks of temples and shrines; a similar office oversaw the much

UNIFICATION, CONSOLIDATION, AND TOKUGAWA RULE 75

revived imperial household.

23

Foreign affairs, a very modest issue for much of the

period, were the provenance of the sho

¯

gun for the most part, and the first late

eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century efforts of Russians, Englishmen, and

Americans to land at various places throughout Japan and Hokkaido

¯

were met with

instructions to go through shogunal channels.

Mid- and late Tokugawa sho

¯

guns were able to use their prestige and authority in

diversity disputes to chip away at daimyo

¯

autonomy or limit the extension of their

economic reach, but Japan lacked the substantial and extended external threats that

compelled Spain, France, and England (for exam ple) to aggressively compromise

baronial autonomy and strengthen the state apparatus. James White notes the degree

to which the sho

¯

gun monopolized legitimate use of force, and Conrad Totman

explores cases of shogunal initiative in public works, but such developments did not

result in any integration of domains into a sho

¯

gun-directed administrative struc-

ture.

24

Indeed, one may read the sho

¯

gun’s effort to create a consensus through

consultation with daimyo

¯

after Perry’s arrival as an indication of its rather tenuous

perch on the top of the Tokugawa political heap. Had it felt in a clearly superior

position it is unlikely that this tactic would have been thought useful or necessary.

Yet truth be told, this impression derived from recent scholarship may be a result of

the small number of scholars in the field. We have article-length studi es of mid-

Tokugawa sho

¯

guns such as Tsunayoshi (r. 1680–1709 and the so-called ‘‘Dog

Sho

¯

gun,’’ famous fo r issuing an edict protecting animals from maltreatment), but

no extended treatment of their reigns or that of any other sho

¯

gun other than

Ieyasu.

25

We have an overview of politics in the bakufu, a monographic treatment

of one intellectual, Arai Hakuseki, who sought unsuccessfully to extend the authority

of the sho

¯

gun, and treatments of two other eighteenth-century shogunal advisors

(Tanuma Okitsugu and Matsudaira Sadanobu), but little else.

The issue of early modernity extends into the realm of Japan’s relationships with

and views of non-Japanese. While modern states typically do not conduct economic

relations with regions outside their sphere of formally established diplomati c rela-

tions, and while such relationships typically specify clearly recognized territorial

boundaries, both characteristics were absent in sixteenth- to mid-nineteenth-century

Japan. For example, Japan had no formal diplomatic ties with China, yet continued

trade with China at Nagasaki. Both C hina and Japan exercised suzerainty over the

Ryu

¯

kyu

¯

Islands, and the Japanese were clearly aware of the ambiguous status of the

archipelago. The international order was seen as rigi dly rank-conscious and the idea

of equality of states (and peoples) was simply not ascendant. While this situation

allowed a significant porous quality to Japan’s relationship with its immediate neigh-

bors, it would not survive the modern treaty system that Perry introduced in 1854.

26

National Integration and the Spread of a Popular National

Consciousness

One part of the system of daimyo

¯

control, the sankin ko

¯

tai system compelled daimyo

¯

attendance in the sho

¯

gun’s capital at Edo for alternate years and kept family members

hostage when the daimyo

¯

was not present. This ar rangement not only helped to

maintain the peace, it also furthered national integration at multiple social levels. The

76 PHILIP C. BROWN

gathering of powerful families in one place furthered the exchange of ideas among

them, including those on how to administer their domains. In Edo, they competed

with each other not only for prestige and honor in both the shogunal and imperial

ranks, but also as administrators. By the late seventeenth century, for example, it was

widely noted that in administrative effectiveness, the domain of Kaga was number

one, Tosa number two. Models of land taxation, administrative structure, economic

policy, and reform spread through discussions among daimyo

¯

and their subordinates

while resident in Edo. Daimyo

¯

could learn how administrative initiatives were going

in other domains and could evaluate what they might learn for use in their own

territories.

In order to maintain the system of alternate attend ance, a national system of major

highways develope d under shogunal leadership. Pock-marked with inspection bar-

riers, these served to channel daimyo

¯

and other administrators’ traffic and permitted

inspection of domestic passports (especially for the powerful and their minions).

Staffed through special local taxation, these networks attracted opportunists of all

stripes, ever ready to earn a few coppers from travelers. Inns, houses of drink and

assignation, souvenir shops, and the like increasingly populated the most well-trav-

eled highways. The attraction was clear: a daimyo

¯

entourage could consist of hun-

dreds of people, all passing along the same route at one time.

In combination with the costs of maintaining a fully staffed household in Edo, the

expenses of sankin ko

¯

tai cost daimyo

¯

approximately a third to one-half of their annual

budgets. This meant that taxes raised largely in kind in a domain had to be converted

to cash for expenditure in travels to and from Edo as well as for maintenance of the

Edo residence. For most domains this meant shipping tax goods (primarily rice) to

Osaka for sale, a process that made the city the center of a well-integrated and truly

national market.

The markets and roads designed to contro l and supply daimyo

¯

could not be limited

to those purposes. They ultimately facilitated the movement of goods, people, ideas,

and fashion throughout Japan, increasing commoner awareness of a shared culture vis-

a

`

-vis China and the world, even though it was a culture marked by regional variations

that were often viewed hierarchically by political, intellectual, and cultural elites.

The Short Arm of the Law

One of the cor ollaries of rethinking the power of the sho

¯

guns has been a general re-

evaluation of the reach of the state, whether daimyo

¯

or sho

¯

gun. While acknowledging

the presence of overlord’s laws, Herman Ooms has shown in a series of studies that

local leaders, commoner leaders, were perfectly capable of marshaling their own

interpretation of (for example) laws on outcaste groups to promote their own

agendas rather than those of a domain or sho

¯

gun.

27

In part this ability is a conse-

quence of the semi-autonomous standing of local commoner governments, but it is

equally important to remember that this arrangement made sense because of the

limitations of communications technology of the day: in an age of poor (by modern

standards) communications, transaction costs of much administ ration and justice

were shifted to local bodies, limiting the need for daimyo

¯

and sho

¯

gun alike to field

larger forces of their own salaried employees into the cities, towns, and villages of the

UNIFICATION, CONSOLIDATION, AND TOKUGAWA RULE 77