Tsutsui W.M. A Companion to japanese histоry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Literary Production

With the establishment and rapid spread of a printing and publishing art over the

course of the early modern period, Japanese literature entered a dynamic phase of

development, in whi ch writers and poets for the first time could make a living from

their publications, and in which readership expanded with each generat ion. Men and,

to an ever greater degree, women exerted increasing influence on what would be

published, as the existence of ‘‘bestsellers’’ came to determine (regardless of the

wishes of bureaucratic censors) the market for a particular title or series of titles. As

Peter Nosco aptly notes, ‘‘popular culture is culture that pays for itself.’’

13

The major literary form of the seventeenth century is the kana-zo

¯

shi, or ‘‘books in

the phonetic kana syllabary.’’ Types of literature covered by this catch-all term

include printed versions of the Heian classics, romances, war narratives, ghost story

collections, humorous anecdotes, travel guides, literary parodies, ratings of cour-

tesans and actors, and didactic works such as manners guides for young women.

Most of the works were published in the Kamigata, but received distribution

throughout the country, mainly through the existence of lendi ng libraries, by which

readers could borrow books for a small fee from itinerent librarians who would return

a few weeks later, collect the borrowed books, and lend out more. What these works

provided for the first time in Japanese history were, first, access to knowledge of the

past and present and, second, the opportunity for reading entertainment, to anyone

who could read basic Japanese. Writers such as Asai Ryo

¯

i(c.1612–91) wrote collec-

tions of ghost stories translated from Chinese sources and adapted to a domestic

setting, travel guides to the provinces, especially along the To

¯

kaido

¯

, or Eastern

Coastal Highway, collections of didactic tales and stories for moral edification, and

stories of contemporary life and habits. In his Ukiyo monogatari (‘‘Tales of the

Floating World,’’ Kyoto, 1661) Ryo

¯

i’s narrator distinguishes between the earlier

Warring States era ukiyo, written with characters signifying ‘‘melancholy world’’

and the contemporary ukiyo, written with the characters for a ‘‘floating world.’’

‘‘Cross each bridge as you come to it; gaze at the moon, the snow, the cherry

blossoms, and the bright autumn leaves; recite poems; drink sake

´

; and make merry.

Not even poverty will be a bother. Floating along with an unsinkable disposition, like

a gourd bobbing allong with the current – this is what we call the floating world.’’

14

Building upon the now established success of the kana-zo

¯

shi, the novelist and

haikai master Ihara Saikaku (1642–93) was able to move the writing of fiction into

a sphere of contemporary verisimilitude (this is unlike modern ‘‘re alism’’ due in part

to the stylized nature of the language employed) that had not been present before.

Son of a successful Osaka merchant, Saikaku us ed his powers of obs ervation, finely

honed after years of haikai poetic composition, and crafted highly readable and

visually compelling stories of longing and lust, martial honor and justice (often

from a perspective of homoerotic loyalty between samurai), and the fluid nature of

money and its relation to desire in a mercantile society. Such books, beginning with

Saikaku’s Ko

¯

shoku ichidai otoko (literall y, ‘‘An Uninhibited Man of a Single Gener-

ation,’’ implying that he left no heir, 1682), offered readers with a contemporary feel,

a less than obvious moral (in spite of moralist prefaces to many of the stories ), and a

source of knowledge about contemporary fashions and mores that spawned imitators

128 LAWRENCE E. MARCEAU

and successors, continuing well into the latter half of the eighteenth century. After

the demise of these books, known as ukiyo-zo

¯

shi, or ‘‘books of the floating world,’’

early-nineteenth-century authors rediscovered Saikaku, and his writings have since

continued to generate interest amon g scholars and general readers.

In the eighteenth century, the development of the publishing industry in Edo

brought with it the appearance of new literary genres, as well as a strengthened sense

of cultural autonomy from the traditional center, Kyoto. We have noted the emer-

gence of new, multicolor prints created in Edo workshops, and, in fiction as well,

fresh forms arose from the brash and innovative Edo milieu. One such form, devel-

oped in the context of a new political atmosphere of cultural flexibility in the wake of

Sho

¯

gun Tokugawa Yoshimune’s (1684–1751, in power 1716–45) Kyo

¯

ho

¯

Reforms of

the 1720s and 30s, was the dangibon (‘‘sermon books’’ ), which attracted readers in

Edo in the mid eighteenth century. One result of Yoshimune’s reforms was the

promotion of learning among commoners, which led to the appearance of Buddhist

or quasi-Buddhist ‘‘preachers’’ on stree t corners in Edo and other cities. Some of

these preachers recorded and published the ir sermons for an even broader audience.

The distinctive feature of the dangibon is their humorous and satirical nature, in

which the reader attempts to ‘‘unearth’’ (ugachi) the fad or current practice in

contemporary Edo society that is being lampooned. The great master of this biting

satirical style was Hiraga Gennai (1728–80), a samurai in service to a provincial lord

who left his region, reloca ted to Edo, and involved him self in a variety of scientific and

literary projects. Well versed in Dutch Studies (rangaku, the term for European

scientific studies in Japan), Gen nai classified flora and fauna according to principles

of materia medica, explored the medical uses of electricity, and made the first fire-

resistant fabric in Japan using asbestos. While in many ways resembling his contem-

porary, Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), Gennai lived within a power establishment

that was not flexible enough to absorb his ideas. The frustrated Gennai (who wrote

under the sobriquet Fu

¯

rai Sanjin, or ‘‘mountain dweller who comes on the wind’’)

turned to the biti ng humor of the dangibon to give vent to his disaffection with the

current state of affairs.

The fictional genre that featured the greatest psychological depth, as well as

the greatest capacity for a large-scale epic structure is the yomihon, or ‘‘reading

book,’’ so named because illustrations were limited to a few pages, in contrast to an

overwhelming amount of text. Origin ating in the Kamigata with the works of

physician and author Tsuga Teisho

¯

(1718–c.1794), early yomihon were collections

of stories, usually of an occult nature, that combined influences from Chinese

vernacular collections of the Ming and early Qing dynasties (fourteenth to seven-

teenth centuries) that were written not in standard literary Chinese of the classics, but

in a new hybrid form called baihua. Educated Japanese writers and intellectuals who

had maintained contact with Chinese in Nagasaki and at O

¯

baku temples were in-

trigued by this new form of Chinese, and were eager to use the works written in

baihua to enhance their own narratives. Ueda Akinari (1734–1809), adopted son of

an Osaka paper and oil me rchant and author of the masterful Ugetsu monogatari

(Tales of Rain and Moon, 1776), wove together nine suspenseful narratives from a

rich blend of native and imported sources, endowing them with his heartfelt concern

for human frailty, and the seemingly unlimited capacity we have both to help and to

hurt one another.

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS IN TOKUGAWA JAPAN 129

The yomihon genre was transferred to the publishing world in Edo in the 1790s

through the work of the multi-talented writer Santo

¯

Kyo

¯

den (1761–1816), son of an

Edo pawnbroker. Kyo

¯

den took the Kamigata yomihon and transformed them into a

kabuki-like vehicle for fantastic occurrences, epic struggles, and larger than life heroes

and villains. The great master of the Edo yomihon, though, was Kyokutei Bakin

(1767–1849, also known by his surname of Takizawa), a member of the bushi class

who left his hereditary status and became a disciple in writing of Kyo

¯

den. Bakin

extended and expanded Kyo

¯

den’s style in the yomihon and left a prodigious number

of bestsellers, including, most notably, his masterpiece Nanso

¯

Satomi Hakkenden

(Lives of the Eight Dog-Heroes of the Nanso

¯

Satomi Clan, 1814–42). This massiv e

work, loosely based on the Chinese baihua epic, Shui hu zhuan (‘‘Water Marg in,’’

also ‘‘Outlaws of the Marsh,’’ etc., narrated and rewritten by multiple authors over

the fourte enth to seventeenth centuries), tells of the virtuous actions of eight heroes,

each of whom had been endowed with a magical jewel expressing one of eight

fundamental Confucian virtues . Bakin couches his nar rative in a didactic frame work

of ‘‘promoting good and chastising evil’’ (Ch., quanshan chengwu; J., kanzen

cho

¯

aku), but the astute reader of his time could sense something latent (inbi, one of

Bakin’s own ‘‘Seven Rules Governing the Historical Novel’’ outlined in a preface to

Hakkenden) to be found between the lines of h is narrative. This latent or hidden

message may have to do with the ironic distance between the virtuous heroes and the

corrupt world within which they act, or it may deal with the distance between the

ideals themselves and how they play through in an imperfect world. For Bakin, the

juxtaposition between an overtly didactic framework and a more subtle reading

provides a tension that makes his work compelling even today.

Kyo

¯

den and Bakin worked in other genres of Edo fiction as well. Including the

yomihon, these styles and formats of popular, often humorous, narrative are referred

to as gesaku, or ‘‘playful works,’’ and the authors of these works, gesa kusha. Gesaku

include the witty and fully illustrated kibyo

¯

shi, or ‘‘yellow covers,’’ in which the text is

embedded together as part of the illustration in a manner much like today’s comic

books. However, the content was clearly not for children, given that kibyo

¯

shi were

parodies of the foibles of adult life. In the early 1790s the government suppressed

these works for having gone too far in lampooning official edicts, and for the final

decade of their existence, kibyo

¯

shi steered clear of sensitive issues. Another genre, share-

bon, or ‘‘books of wit,’’ were actually tales of current fashions within the pleasure

quarters, and were written in such a mann er that in many cases only those fully

conversant (tsu

¯

) with the language and customs of such districts would be able to

understand the details. In the early nineteenth century, the sharebon yielded to the

ninjo

¯

bon (books of human emotions), which dealt with troubled love affairs between

courtesans and customers, both wealthy an d humble. Tamenaga Shunsui (1790–

1844), son of an Edo publisher-bookseller, was the leadi ng author of this genre, and

his works such as Shunshoku Umegoyomi (Spring Colors: The Plum Calendar, 1832–3)

generated massive followings, especially among female readers. The earlier satirical

dangibon paved the way for the comic

kokkeibon

, which is best represented by two

Edo authors. Jippensha Ikku (1765–1831) made his reputation with the series, To

¯

kai-

do

¯

chu

¯

Hizakurige (Trotting along the Eastern Co astal Highway, 1802–9). This linear

narrative follows a pair of hapless good-for-nothing heroes through episode after

episode of slapstick adventures, and proved to be a runaway bestseller, not only due to

130 LAWRENCE E. MARCEAU

the strength of the narrative and the attraction/repulsion of the two protagonists, but

also for the details provided about the various scenes and sights along the way. The other

author to succeed at hum orous fiction was Shiki tei Sanba (1776–1822), son of a

woodblock carver in Edo. Sanba’s most memorable works, Ukiyo-buro (Bathhouse of

the Floating World, 1809–13) and Ukiyo-doko (Barber Shop of the Floating World,

1813–14), take the conceit of Ikku’s Hizakurige, and reverse it, so that, instead of a

world in which two characters move through time and space, the reader enjoys a static

world (men’s bathhouse, women’s bathhouse, or hairdresser’s) through which various

characters ent er, exit, and re-enter as the narrative progresses. In both cases the language

employed is vernacular to the extreme, and the level of imme diacy is such that reading

these works today generates a sense of having literally slipped into a world populated by

the streetwise townsfolk of Edo and the more rustic inhabitants of the provinces.

The image-oriented kibyo

¯

shi were in the final decades of the early modern period

replaced by longer go

¯

kan or go

¯

kanbon, which were literally ‘‘combined volumes’’ of

short chapbooks that were brought together within paper wrappers to form longer

works. In exchange for the more substantial length of the go

¯

kan, the effort that had

been previously made by the graphic artist to provide an interesting visual image was

replaced now by prints of the main characters surrounded completely by text. Thus,

while still image–text combinations, clearly at this point the text provides the content

and main interest for the reader, while the image merely serves to identify the

characters deli vering the textual dialogue. The most successful author of go

¯

kan was

Ryu

¯

tei Tanehiko (1783–1842), a low-ranking samurai raised in Edo. His major work,

and most likely the bestseller of fiction in the entire early modern period is his Nise

Murasaki inaka Genji (A False Murasaki’s Rustic Genji, 1829–42). With regard to

sales, Andrew Markus rep orts, ‘‘Inaka Genji was in a class by itself: . . . Aeba Ko

¯

son

insists on sales of 14,000 to 15,000 copies for Inaka Genji, even at (an) exorbitant

price.’’

15

As the title implies, this work takes the milieu and many of the characters of

the Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji, c.1008) and transfers them to the very

different world of contemporary Edo. Together with the other works mentioned

above, the success of Nise Murasaki inaka Genji demonstrates dramatically the

complex development of the fiction publishing world in Japan from the seventeenth

through the nineteenth centuries.

In poetry, over the course of the early modern period the following developments

occurred: the continuation and diffusion of the representat ive verse form, the thirty-

one-syllable waka; a revival among some poets of the archaic extended form, the cho

¯

ka;

expansion and increased range of expression in Chinese poetic forms (kanshi); the

development of humorous verse forms in Japanese and Chinese (kyo

¯

ka, kyo

¯

shi), in

tandem with the eighteenth-century appearance of satirical narrative forms; and,

above all else, the development of a new, less formal verse form in both stand-alone

and linked-verse modes, the seventeen-syllable haikai, together with its ‘‘grass-roots’’

offshoot, senryu

¯

.

Waka poetry, the identifying feat ure of Kyoto court life since before the Heian

period, continued unabated throughout the early modern period. Access to secret

traditions expanded after warrior general Hosokawa Yu

¯

sai (1534–1610) received the

transmissions of the Kokin denju (‘‘esoteric knowledge concerning the Kokin waka-

shu

¯

’’) from a member of the court aristocracy. Court poets continued to compose

waka following received forms, while, among samurai and commoner poets, new

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS IN TOKUGAWA JAPAN 131

approaches to waka were reflected in their poetry. Scholars such as Keichu

¯

(1640–1701), a warrior turned Buddhist priest in Osaka; Kamo no Mabuchi

(1697–1769), born into a line of Shinto

¯

priests and active in Edo; Kada no Arimaro

(1706–51), also hailing from a line of Shin to

¯

clergy; Tayasu Munetake (1715–71), son

of the eighth sho

¯

gun, Yoshimune; Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801), son of a provincial

merchant; Ozawa Roan (1723–1801), samurai resident in Kyoto; and Kagawa Kageki

(1768–1843), son of a low-ranking domainal vassal, all provided new and innovative

ideas, backed by solid scholarship in the classics, which opened up waka composition to

all who expressed an interest. By early Meiji, Kageki’s school had emerged as the

‘‘orthodox school,’’ supported by the imperial court, while the old esoteric transmis-

sions had been abandoned in favor of the new open scholarship into the classics.

As we have seen with narrative fiction, more ‘‘serious’’ forms of poetry became the

object of satire and humorous metaphor. For example, in waka, a ‘‘deranged’’ form,

called kyo

¯

ka, appeared, and was explosively popular, especially in Edo, during the

An’ei and Tenmei h eyday of early modern culture (1772–89). Chinese poetry, that

most serious and difficult form for the Japanese, also had its ‘‘deranged’’ adversary,

called kyo

¯

shi, which necessarily had a more limited following.

Haikai, haikai drawings called haiga, and haikai-inspired poetic prose called

haibun all arose during the early modern period. Schools of haikai composition

competed with one another for pupils, and the results of their gatherings were

published and read in great numbers. One poet attempted to rise above the com-

petitive nature of the art as it was developing and work tow ard haikai as a type of

‘‘way’’ or michi. This was the ‘‘Sage of Haikai,’’ Matsuo Basho

¯

(1644–94), born into

a family in the provinces at the lowest end of the warrior class. Works such as his Oku

no hosomichi (Narrow Way to the Depths, 1702) are considered the apex of a zoku,or

popular, form achieving the heights of a ga, or refined, sensibility toward life and the

world. The most gifted haikai poets after Basho

¯

include Yosa Buson (1716–84) and

Kobayashi Issa (1763–1827), both of agrarian backgrounds who each in his own way

took haikai composition in a new and individualistic direction.

The world of publishing, following the accepted patter n of male inheritance of the

proprietor’s name from generation to generation, was in effect closed to women. This

meant that, with few exceptions, women writers of narrative fiction and female print

artists were excluded from the publishing system. Poet ic composition, which had,

especially in the realm of waka, from earliest times served both as an expressive outlet

and as an important form of social interaction, remained open to women as well as to

men. Thus we find wom en as participants in waka and haikai poetic gathering s, and

their poems published with men’s works in poetic compilations and private collec-

tions throughout the period. The scholar of nativist studies (wagaku or kokugaku)

Kamo no Mabuchi (1697–1769) was particularly active in admitting women to his

school of the Japanese classics and poetics in Edo, and it is reported that ‘‘nearly one-

third of [Mabuchi’s] students at the end of his life were women – a figure among the

highest of any major private academy in Tokugawa Japan. . . . In fact, there were

more women students in Mabuchi’s school than merchants and agriculturalists

combined, and more than twice as many women as samurai.’’

16

Important literary

women include the following: in the realm of waka composition, the so-called ‘‘Three

Talented Women of Gion’’: Kaji (fl. c.1700), Yuri (d. 1757), and Machi (1727–84,

also known as the artist Tokuyama Gyokuran, spouse of bunjin Ike no Taiga); the

132 LAWRENCE E. MARCEAU

so-called ‘‘Three Poetic Talents of the Mabuchi School’’: Toki Tsukubako (fl. 1750),

Udono Yonoko (1729–88), and Yuya Shizuko (1733–52); also Kada no Tamiko

(1722–86), O

¯

tagaki Rengetsu (1791–1875), and Nomura Bo

¯

to

¯

(also Nomura

Noto, 1806–67 ). In the sphere of wabun, or composition of prose in archaic styles,

we should recognize Arakida Rei (1732–1806) and Tadano Makuzu (1763–1825).

Among kyo

¯

ka poets we find Chie no Naishi (1745–1807, spouse of kyo

¯

ka circle leader

Moto no Mokuami, 1724–1811), and Fushimatsu no Kaka (1745–1810, another

spouse of circle leader Akera Kanko

¯

, 1738–99). There are several notable female

haikai poets, the most well known being Kaga no Chiyo (1703–75). Finally, in the

male-dominated world of kanshi composition, three names stand out: Ema Saiko

¯

(1787–1861), Cho

¯

Ko

¯

ran (1804–79, spouse of kanshi poet Yanagaw a Seigan, 1789–

1858), and Hara Saibin (1798–1859). Of course Yoshiwara and Shimabara cour-

tesans were renowned for their poetic skills as well, especially at the apex of pleasure

district culture in the mid to late eighteenth century.

Thus we see that the culture encountered by Europeans in the early seventeenth

century developed in highly distinctive ways over the next 265 years. With the spread

of literacy and education, publishing became a medium of information, edification,

and entertainment that no one could do without. The arts and literature exhibited

repeated phases of popularity, decline, and renewed popularity in ever expanding

forms, and in the social sphere, the daimyo

¯

and other military bureaucrats came to

emulate wealthy merchants while merchants lived as though they themselves were

daimyo

¯

. Urban networks thrived in spite of governmental security concerns, and

information spread from the urban centers out to the hinterlands and back again.

By the time the next wave of pressure arrived from the West in the middle decades of

the nineteenth century, the Japanese had far outgrown their seventeenth-century

system of order-based Tokugawa control, and were more than ready to extend, and

expand, their cultural development in yet other directions.

NOTES

1 Cooper, comp. and annot., They Came to Japan, pp. 277, 280, and 60, respectively.

2 Hickman et al., Japan’s Golden Age, pp. 19–56.

3 Nakano Mitsutoshi, ‘‘The Role of Traditional Aesthetics,’’ pp. 124–5.

4 Totman, Early Modern Japan, pp. 152–3.

5 Henry D. Smith II, ‘‘The Floating World in Its Edo Locale 1750–1850,’’ in Jenkins, The

Floating World Revisited, p. 38.

6 Kornicki, The Book in Japan, pp. 114–15.

7 Cooper, comp. and annot., They Came to Japan, pp. 251–2.

8 Kornicki, The Book in Japan, p. 140.

9 Lawrence Marceau, ‘‘Hidden Treasures from Japan: Wood-Block-Printed Picture Books

and Albums,’’ in Kita, Marceau, Blood, and Farquhar, The Floating World of Ukiyo-e, p. 84.

10 Cleary, trans., The Code of the Samurai,p.3.

11 Ibid., p. 95.

12 Graham, Tea of the Sages, p. 49.

13 Nosco, Remembering Paradise, p. 16.

14 Jack Stoneman, in Shirane, ed., Early Modern Japanese Literature, p. 30.

15 Markus, The Willow in Autumn, pp. 146–7.

16 Nosco, Remembering Paradise, p. 145.

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS IN TOKUGAWA JAPAN 133

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cleary, Thomas, trans. The Code of the Samurai: A Modern Translation of the Bushido

¯

shoshinshu

¯

of Taira Shigesuke. Rutland, Vt.: C. E. Tuttle, 1999.

Cooper, Michael, comp. and annot. They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on

Japan, 1543–1740. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965; repr. 1981.

Gerstle, C. Andrew, ed. Eighteenth Century Japan: Culture and Society. London: Routledge-

Curzon, 2000.

Graham, Patricia. Tea of the Sages: The Art of Sencha. Honolulu: University of Hawai i Press,

1998.

Hickman, Money, et al. Japan’s Golden Age: Momoyama. New Haven: Yale University Press,

1996.

Jenkins, Donald. The Floating World Revisited. Portland, Ore.: Portland Art Museum, 1993.

Kita, Sandy, Marceau, Lawrence E., Blood, Katherine, and Farquhar, James Douglas. The

Floating World of Ukiyo-e: Shadows, Dreams, and Substance. New York: Harry N. Abrams,

2001.

Kornicki, Peter. The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth

Century. Leiden: Brill, 1998.

Markus, Andrew. The Willow in Autumn: Ryu

¯

tei Tanehiko, 1783–1842. Cambridge, Mass.:

Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1992.

Nakano Mitsutoshi, ‘‘The Role of Traditional Aesthetics.’’ In C. Andrew Gerstle, ed., Eight-

eenth Century Japan: Culture and Society. Richmond, UK: Curzon, 1989.

Nosco, Peter. Remembering Paradise: Nativism and Nostalgia in Eighteenth-Century Japan.

Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1990.

Shirane, Haruo, ed. Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology 1600–1900. New York:

Columbia University Press, 2002.

Totman, Conrad. Early Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

FURTHER READING

In the field of literature, Haruo Shirane, ed., Early Modern Japanese Literature: An

Anthology 1600–1900 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), is required

reading. Samuel Leiter’s New Kabuki Encyclopedia (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood,

1997) provides much detail, not only for kabuki, but for popular culture in general.

For art, Robert T. Singer et al., Edo: Art in Japan 1615–1868 (Washington DC:

National Gallery of Art, 1998) provides full-color exa mples of hundreds of art works

encompassing a wid e range of types, supplemented by essays written by leading

scholars. Chris tine Guth’s Art of Edo Japan: The Artist and the C ity (New York:

Harry N. Abrams, 1996) is an excellent survey of painters and printmakers through-

out early modern Japan. Richard Lane’s Images from the Floating World: The Japanese

Print (New York: Putnam, 1978) serves both as an interpretive history and as a

dictionary of woodblock print artists and their works.

Two fine books and a CD-ROM provide valuable perspectives with regard to the

city of Edo, which grew over the course of the period to become the major metrop-

olis of the land. The first, Nishiyama Matsunosuke’s Edo Culture: Daily Life and

Diversions in Urban Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai i Press, 1997) is a well-

illustrated translation of essays on Edo by the foremost ‘‘Edo studies’’ scholar in

Japan. For a visual understanding of Edo, Naito Akira and Hozumi Kazuo’s Edo, the

134 LAWRENCE E. MARCEAU

City that Became Tokyo: An Illustrated History (Tokyo: Ko

¯

dansha International,

2003) provides myriad line drawings of various aspects of life in the metropolis

together with informative English-translated text. Kidai Sho

¯

ran: Excellent View of

Our Prosperous Age (Berlin: Museum fu¨r Ostasiatiche Kunst, 2000) is a multimedia

CD-ROM that provides a cross-section of life on the main commercial avenue at

Nihonbashi in Edo, c.1805, from a beautifully detailed illustrated handscroll, and is

meticulously annotated in English and German.

Peter Kornicki’s The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the

Nineteenth Cent ury (Leiden: Brill, 1998) explores the impact publishing and print

culture made on the Japanese, especially through the early mod ern period. Chapters 6

through 9 of H. Paul Varley’s Japanese Culture (Honolulu: Unive rsity of Hawai i

Press, 2000), now in its fourth revised edition, provide a lucid general background to

early modern Japanese cultural history. Likewise, Donald H. Shively’s chapter,

‘‘Popular Culture,’’ in The Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 4, Early Modern

Japan, ed. John Whitney Hall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), is

extremely useful for garnering a sense of the ro les played by popular culture in Japan

at the time. Finally, four chapters included in Conrad Totman’s authoritative Early

Modern Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993) focus on cultural

developments.

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS IN TOKUGAWA JAPAN 135

PART III

Modern Japan: From the Meiji

Restoration through World War II

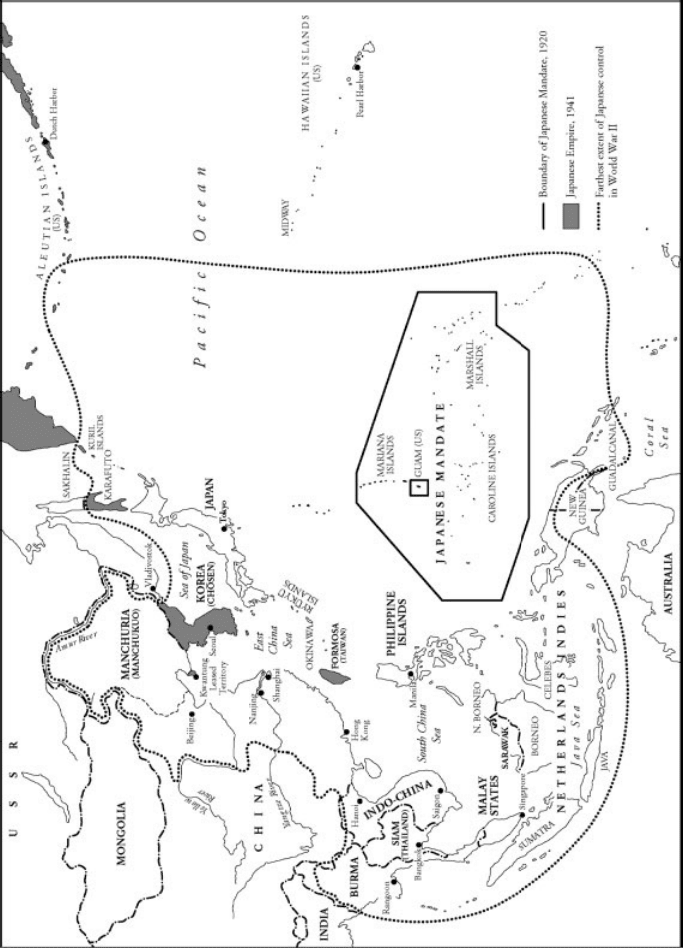

Map 3 The Japanese empire