Tietenberg Tom, Lewis Lynne. Environmental & Natural Resource Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

571Effects of Population Growth on Economic Development

L(t

1

) L(t

2

) L(t

3

)

P(t

1

)

A

B

P(t

2

)

P(t

3

)

M(t

1

)

M(t

2

)

M(t

3

)

Marginal Product of Labor

(units of output)

Quantity

of Labor

0

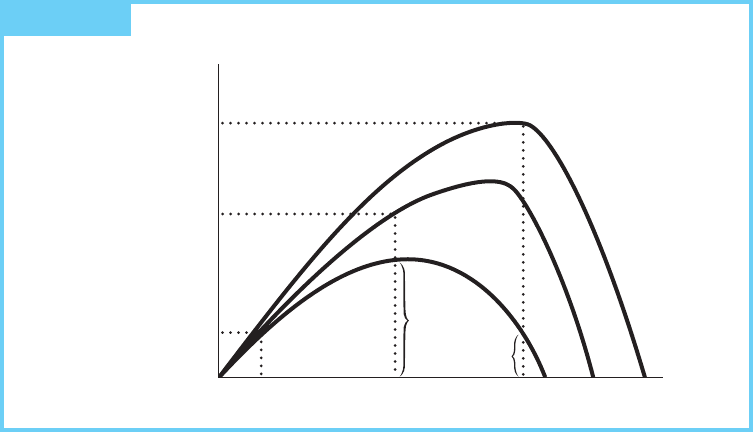

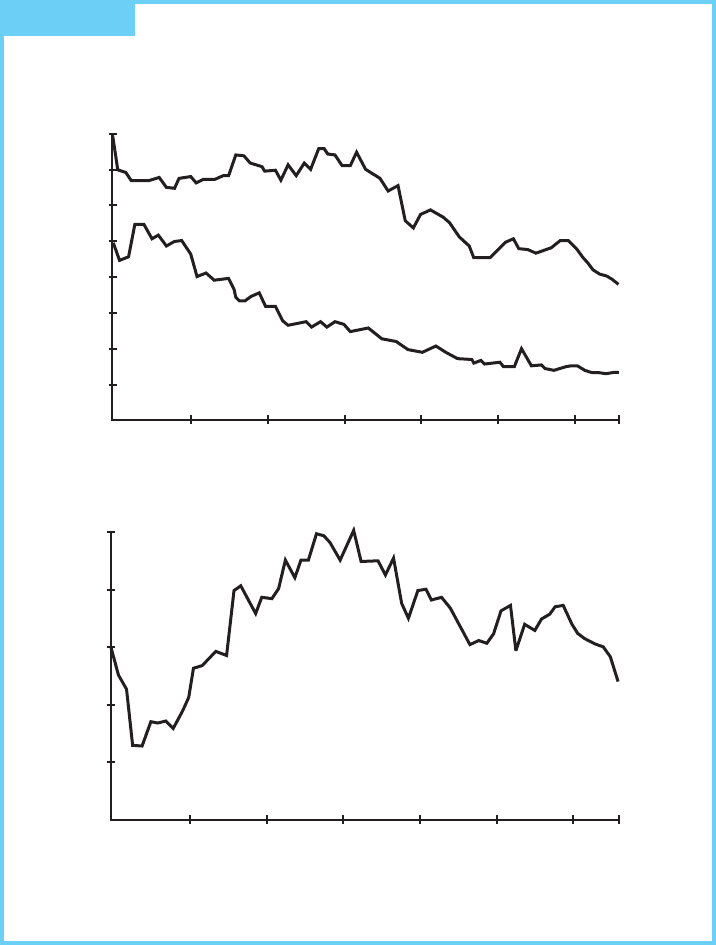

FIGURE 21.3 Technological Progress and the Law of Diminishing Returns

Not all arguments suggest that growth in output per capita will be restrained by

population growth. Perhaps the most compelling arguments for the view that

population growth enhances per capita growth are those involving technological

progress and economies of scale (see Figure 21.3).

The vertical axis shows marginal productivity measured in units of output. The

horizontal axis describes various levels of labor employed on a fixed amount of

land. Population growth implies an increase in the labor force, which is recorded

on the graph as a movement to the right on the horizontal axis.

The curve labeled P(t

1

) shows the functional relationship between the marginal

product of labor and the amount of labor employed on a fixed plot of land at a

particular point in time (t

1

). Different curves represent different points in time

because in each period of time there exists a unique state of the art in the knowl-

edge of how to use the labor most effectively. Thus, as time passes, technological

progress occurs, advancing the state of the art and shifting the productivity curves

outward, as demonstrated by P(t

2

) and P(t

3

).

Three situations are demonstrated in Figure 21.3. At time t

1

, an application of

L(t

1

) yields a marginal product of M(t

1

). At times t

2

and t

3

, the application of L(t

2

)

and L(t

3

) units of labor yield M(t

2

) and M(t

3

) marginal units of output, respectively.

Marginal products have increased as larger amounts of labor were added.

Consider what would have happened, however, if the state of technical

knowledge had not increased. The increase in labor from L(t

2

) to L(t

3

) would have

been governed by the P(t

1

) curve, and the marginal product would have declined

from A to B. This is precisely the result anticipated by the law of diminishing

marginal productivity. Technological progress provides one means of escaping the

law of diminishing marginal productivity.

572 Chapter 21 Population and Development

The second source of increase in output per worker is economies of scale.

Economies of scale occur when increases in inputs lead to a more-than-proportionate

increase in output. Population growth, by increasing demand for output, allows

these economies of scale to be exploited. In the United States, at least, historically

this has been a potent source of growth. While it seems clear that the population

level in the United States is already sufficient to exploit economies of scale, the

same is not necessarily true for all developing countries.

In the absence of trade restrictions, however, the relevant market now is the

global market, not the domestic market. The level of domestic population has little

to do with the ability to exploit economies of scale in the modern global economy

unless tariffs, quotas, or other trade barriers prevent the exploitation of foreign

markets. If trade restrictions are a significant barrier, the appropriate remedy would

be reducing trade restrictions, not boosting the local population.

Because these a priori arguments suggest that population growth could either

enhance or retard economic growth, it is necessary to rely on empirical studies to

sort out the relative importance of these effects. Several researchers have attempted

to validate the premise that population growth inhibits per capita economic

growth. Their attempts were based on the notion that if the premise were true, one

should be able to observe lower growth in per capita income in countries with

higher population growth rates, all other things being equal.

A study for the National Research Council conducted an intensive review of the

evidence. Does the evidence support the expectations? In general, they did not find

a strong correlation between population growth and the growth in per capita

income. However, they did determine the following:

1. Slower population growth raises the amount of capital per worker and, hence,

the productivity per worker.

2. Slower population growth is unlikely to result in a net reduction in

agricultural productivity and might well raise it.

3. National population density and economies of scale are not significantly related.

4. Rapid population growth puts more pressure on both depletable and

renewable resources.

A subsequent study by Kelley and Schmidt found “A statistically significant and

quantitatively important negative impact of population growth on the rate of per

capita output growth appears to have emerged in the 1980s.” This result is consistent

with the belief that population growth may initially be advantageous but ultimately,

as capacity constraints become binding, becomes an inhibiting factor. Kelley and

Schmidt also found that the net negative impact of demographic change diminishes

with the level of economic development; the impact is larger in the relatively impov-

erished less developed countries. According to this analysis, those most in need of

increased living standards are the most adversely affected by population growth.

Rapid population growth may also increase the inequality of income. High

population growth can increase the degree of inequality for a variety of reasons, but

the most important is that high growth has a depressing effect on the earning

capacity of children and on wages.

573Effects of Population Growth on Economic Development

TABLE 21.2 Estimates of Child-Rearing Expenditures

Average Child-Rearing Expenditures as

a Percent of Total Family Expenditure

Economist and

Year of Study Data Years

1

One Child

(in percent)

Two Children

(in percent)

Three Children

(in percent)

Espenshade (1984)

1972–1973 24 41 51

Betson (1990) 1980–1986 25 37 44

Lino (2000) 1990–1992 26 42 48

Betson

2

(2001) 1996–1998 25 35 41

Betson

2

(2001) 1996–1998 30 44 52

Notes

:

1

All estimates were developed using data from the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure

Survey.

2

Betson (2001) developed two separate sets of estimates based on two somewhat different methodologies.

Source

: Policy Studies, Inc., “Report on Improving Michigan’s Child Support Formula” submitted to the

Michigan State Court Administrative Office on April 12, 2002. Available on the Web at

http://www.courts.mi.gov/scao/services/focb/formula/psireport.htm/

The ability to provide for the education and training of children, given fixed

budgets of time and money, is a function of the number of children in the family—

the fewer the children, the higher the proportion of income (and wealth, such

as land) available to develop each child’s earning capacity. Since low-income

families tend to have larger families than high-income families do, the offspring

from low-income families are usually more disadvantaged. The result is a growing

gap between the rich and the poor.

What happens to the marginal cost of an additional child as the number of

children increases? As is evident from Table 21.2, the existing estimates suggest that

child-rearing expenses rise from approximately a quarter of household expenditures

for one-child families to approximately one-half for three-child families. These

estimates also find that the total dollar amount spent on children increases with net

income, but as a percentage of net income, it declines.

Another link between population growth and income inequality results from the

effect of population growth on the labor supply. High population growth could

increase the supply of labor faster than otherwise, depressing wage rates vis-à-vis

profit rates. Since low-income groups have a higher relative reliance on wages for

their income than do the rich, this effect would also increase the degree of inequality.

After an extensive review of the historical record for the United States, historian

Peter Lindert concludes:

There seems to be good reason for believing that extra fertility affects the size and

“quality” of the labor force in ways that raise income inequalities. Fertility, like

immigration, tends to reduce the average “quality” of the labor force, by reducing the

574 Chapter 21 Population and Development

amounts of family and public school resources devoted to each child. The retardation in the

historic improvement in labor force quality has in turn held back the rise in the incomes

of the unskilled relative to those enjoyed by skilled labor and wealth-holders. [p. 258]

Lindert’s interpretation of the American historical record seems to be valid

for developing countries as well. The National Research Council study found

that slower population growth would decrease income inequality, and it would

raise the education and health levels of the children. This link between rapid

population growth and income inequality provides an additional powerful

motivation for controlling population. Slower population growth reduces

income inequality.

The Population/Environment Connection

Historically, population growth has also been held up as a major source of environ-

mental degradation. If supported by the evidence, this could provide another

powerful reason to control population. What is the evidence?

On an individual country level, some powerful evidence has emerged on the

negative effects of population density, especially when it is coupled with poverty. In

some parts of the world, forestlands are declining as trees are cut down to provide

fuel for an expanding population or to make way for the greater need for agricul-

tural land to supply food. Lands that historically were allowed to recover their

nutrients by letting them lay fallow for periods of seven years or longer are now, of

necessity, brought into cultivation before recovery is complete.

As the population expands and the land does not, new generations must either

intensify production on existing lands or bring marginal lands into production.

Inheritance systems frequently subdivide the existing family land among the

children, commonly only male children. After a few generations, the resulting

parcels are so small and so intensively farmed as to be incapable of supplying

adequate food for a family.

Migration to marginal lands can be problematic as well. Generally those lands

are available for a reason. Many of them are highly erodible, which means that they

degrade over time as the topsoil and the nutrients it contains are swept away.

Migration to coastal river deltas may initially be rewarded by high productivity of

this fertile soil, but due to their location, those areas may be vulnerable to storm

surges resulting from cyclones.

In thinking about the long run, it is necessary to incorporate some knowledge of

feedback effects. Would initial pollution pressure on the land result in positive

(self-reinforcing) or negative (self-limiting) feedback effects? (see Debate 21.1).

The traditional means of poverty reduction is economic development. What

feedback effects on population growth is development expected to have? Are devel-

opment and the reduction of population pressure on the environment compatible

or conflicting objectives? The next section takes up these issues.

575The Population/Environment Connection

Does Population Growth Inevitably Degrade the

Environment?

Research in this area has traditionally been focused on two competing hypotheses.

Ester Boserup, a Danish economist, posited a negative feedback mecha-

nism that has become known as the “induced innovation hypothesis.” In her

view, increasing populations trigger an increasing demand for agricultural

products. As land becomes scarce relative to labor, incentives emerge for

agricultural innovation. And this innovation results in the development of more

intensive, yet sustainable land-management practices in order to meet the

food needs. In this case the environmental degradation is self-limiting because

human ingenuity is able to find ways to farm the land more intensively without

triggering degradation.

The opposite view, called the “downward spiral hypothesis,” envisions a

positive feedback mechanism in which the degradation triggers a reinforcing

response that only makes the problem worse.

Clearly these very different visions have very different implications for the role

of population in environmental degradation. Does the evidence suggest which is

right?

Although quite a few studies have been conducted, neither hypothesis always

dominates the other. Apparently the nature of the feedback mechanism is very

context specific. Grepperud (1996) found that as population pressure rose and

exceeded a carrying capacity threshold, land degradation took place in Ethiopia.

Tiffen and Mortimore (2002) found that as family farms became smaller under

conditions of population growth, some people migrated to new areas or took up

new occupations, while others attempted to raise the value of output (crops or

livestock) per hectare. They also found that investments in improving land and

productivity are constrained by poverty.

Kabubo-Mariara (2007) points to the importance of secure property rights in

triggering the Boserup hypothesis in an examination of land conversion and

tenure security in Kenya. Using survey data from a cross section of 1,600 farm-

ers in 1999 and 2000 (73 percent of whom held land under private property), she

tested Boserup’s hypothesis that suggests a correlation between population

density, land conservation, and property rights. She finds that population density

is highest for farmers who have adopted land conservation practices. She also

finds that tenure security is correlated with high population density and farmers

with secure land rights are more likely to adopt soil improvements and plant

drought-resistant vegetation, while common property owners are less likely

to invest in any land improvement. It appears, at least for this case, that the

externalities associated with common property are exacerbated with increased

population densities.

Sources:

Sverre Grepperud, “Population Pressure and Land Degradation: The Case of Ethiopia.” JOURNAL

OF ENVIRONMENTAL ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT, 30 (1996), pp. 18–33; M. Tiffen and

M. Mortimore, ”Questioning Desertification in Dryland Sub-Saharan Africa.” NATURAL RESOURCES

FORUM, 26 (2002), pp. 218–233; Jane Kabubo-Mariara, “Land Conversion and Tenure Security in Kenya:

Boserup’s Hypothesis Revisited.” ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS, 64 (2007), pp. 25–35.

DEBATE

21.1

576 Chapter 21 Population and Development

Effects of Economic Development on

Population Growth

Up to this point we have considered the effect of population growth on economic

development. We now have to examine the converse relationship: Does economic

development affect population growth? Table 21.1 suggests that it may, since the

higher-income countries are characterized by lower population growth rates.

This suspicion is reinforced by some further evidence. Most of the industrialized

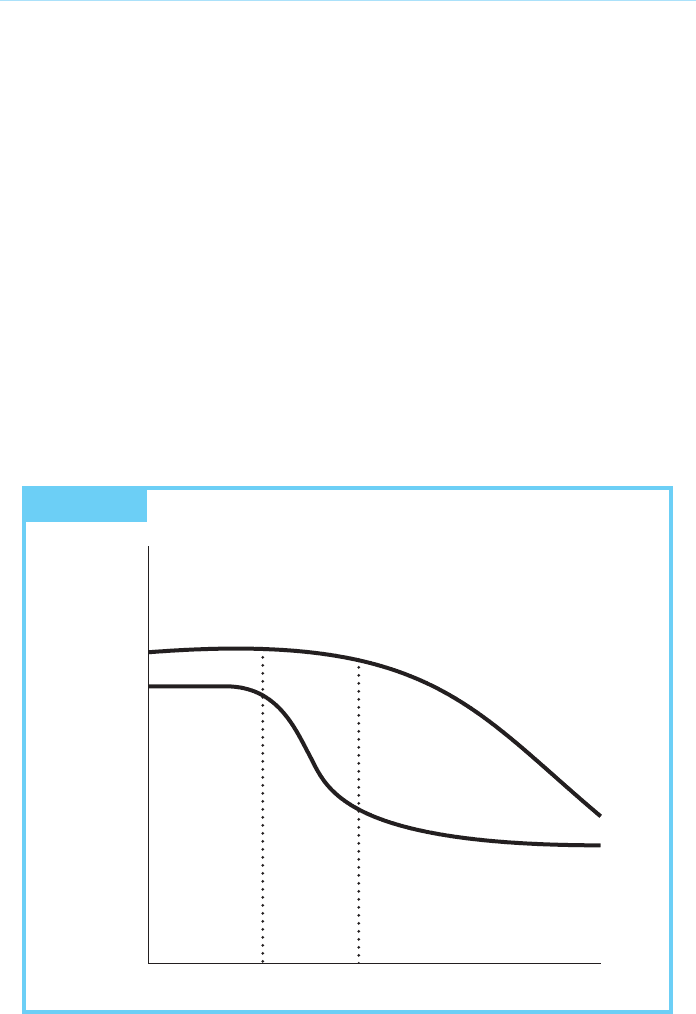

countries have passed through three stages of population growth. The conceptual

framework that organizes this evidence is called the theory of demographic transition.

This theory suggests that as nations develop, they eventually reach a point where

birthrates fall (see Figure 21.4).

During Stage 1, the period immediately prior to industrialization, birthrates are

stable and slightly higher than death rates, ensuring population growth. During Stage

2, the period immediately following the initiation of industrialization, death rates fall

dramatically with no accompanying change in birthrates. This decline in mortality

results in a marked increase in life expectancy and a rise in the population growth rate.

In Western Europe, Stage 2 is estimated to have lasted somewhere around 50 years.

Stage 3, the period of demographic transition, involves large declines in the

birthrate that exceed the continued declines in the death rate. Thus, the period of

demographic transition involves further increases in life expectancy, but rather

Stage 1

Birthrate

Death Rate

Time

Annual

Birth and

Death Rates

per 1,000

Population

Stage 2 Stage 3

FIGURE 21.4 The Demographic Transition

577Effects of Economic Development on Population Growth

smaller population growth rates than characterized during the second stage. The

Chilean experience with demographic transition is illustrated in Figure 21.5. Can

you identify the stages?

One substantial weakness of the theory of demographic transition as a guide to

the future lies in the effect of HIV/AIDS on death rates. Demographic transition

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990

1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990

Rate of Natural

Increase

Percentage

Year

Year

Crude Birthrate

Crude Death Rate

Rate per

1,000

1996

1996

FIGURE 21.5 Annual Birthrates, Death Rates, and Rates of Natural Population

Increase in Chile, 1929–1996

Sources

:

International Historical Statistics: The Americas (1750–1988)

(New York: Stockton, 1993): pp. 76 and 78;

1993

Demographic Yearbook

(United Nations 1995): pp. 294 and 321; and 1997

Demographic Yearbook

(United

Nations 1999), pp. 373 and 403.

578 Chapter 21 Population and Development

theory presumes that with development comes falling death rates and increasing life

expectancy, producing an increase in population growth until the subsequent fall in

birthrates. Approximately 40 million people worldwide are infected with

HIV/AIDS. The AIDS pandemic is so pervasive in some Sub-Saharan African

nations that the resulting large increase in death rates and decrease in life expectancy

are causing population to decline, not increase. According to the U.S. Census

Bureau, Botswana, South Africa, and Zimbabwe are in that position. The average

adult life span in these countries has decreased by 21 years. In 2005, 13.2 million

adult women (58.9 percent of total adults living with HIV) in Sub-Saharan Africa

were infected.

The theory of demographic transition is useful in countries where death rates

have fallen because it suggests that reductions in population growth might

accompany rising standards of living, at least in the long run. However, it also leaves

many questions unanswered: Why does the fall in birthrates occur? Can the process

be hastened? Will lower-income countries automatically experience demographic

transition as living standards improve? Are industrialization or better-designed

agricultural production systems possible solutions to “the population problem”?

To answer these questions it is necessary to begin to look more deeply into the

sources of change behind the demographic transition. Once these sources are iden-

tified and understood, they can be manipulated in such a way as to produce the

maximum social benefit.

The Economic Approach to Population

Control

Is the current rate of population growth efficient? Is it sustainable? The demon-

stration that population growth reduces per capita income is not sufficient to prove

that inefficiency exists. If the reduced output is borne entirely by the families of

the children, this reduction may represent a conscious choice by parents to sacrifice

production in order to have more children. The net benefit gained from having

more children would exceed the net benefit lost as output per person declined.

To establish whether or not population control is efficient, we must discover

any potential behavioral biases toward overpopulation. Will parents always make

efficient childbearing decisions?

A negative response seems appropriate for three specific reasons. First, child-

bearing decisions impose external costs outside the family. Second, the prices of

key commodities or services related to childbearing and/or rearing may be

inefficient, thereby sending the wrong signals. And finally, parents may not be

fully informed about, or may not have reasonable access to, adequate means for

controlling births.

Two sources of market failure can be identified immediately. Adding more

people to a limited space gives rise to “congestion externalities,” higher costs

resulting from the attempt to use resources at a higher-than-optimal capacity.

Examples include too many people attempting to farm too little land and too

579The Economic Approach to Population Control

many travelers attempting to use a specific roadway. These costs are intensified

when the resource base is treated as free-access common property. And, as noted

above, high population growth may exacerbate income inequality. Income equality

is a public good. The population as a whole cannot be excluded from the degree

of income equality that exists. Furthermore, it is indivisible because, in a given

society, the prevailing income distribution is the same for all the citizens of that

country.

Why should individuals care about inequality per se as opposed to simply caring

about their own income? Aside from a purely humane concern for others, particularly

the poor, people care about inequality because it can create social tensions. When

these social tensions exist, society is a less pleasant place to live.

The demand to reduce income inequality clearly exists in modern society, as

evidenced by the large number of private charitable organizations created to fulfill

this demand. Yet because the reduction of income inequality is a public good, we

also know that these organizations cannot be relied on to reduce inequality as much

as would be socially justified.

Parents are not likely to take either the effect of more children on income

inequality or congestion externalities into account when they make their

childbearing decisions. Decisions that may well be optimal for individual families

will result in inefficiently large populations.

Excessively low prices on key commodities can create a bias toward inefficiently

high populations as well. Two particularly important ones are (1) the cost of food,

and (2) the cost of education. It is common for developing countries to subsidize

food by holding prices below market levels. Lower-than-normal food prices

artificially lower the cost of children as long as the quantities of available food are

maintained by government subsidy.

1

The second area in which the costs of children are not fully borne by the parents

is education. Primary education is usually state financed, with the funds collected by

taxes. The point is not that parents do not pay these costs; in part they do. The point

is rather that their level of contribution is not usually sensitive to the number of

children they have. The school taxes parents pay are generally the same whether

parents have two children, ten children, or even no children. Thus the marginal

educational expenditure for a parent—the additional cost of education due to the

birth of a child—is certainly lower than the true social cost of educating that child.

Unfortunately, very little has been accomplished on assessing the empirical

significance of these externalities. Despite this lack of evidence, the interest in

controlling population is clear in many, if not most, countries.

The task is a difficult one. In many cultures the right to bear children is

considered an inalienable right immune to influences from outside the family.

Indira Gandhi, the former Prime Minister of India, lost an election in the late

1970s due principally to her aggressive and direct approach to population control.

Though she subsequently regained her position, political figures in other democratic

1

Note, however, that if the food is domestically produced and the effect of price controls is to lower the

prices farmers receive for their crops, the effect is to lower the demand for children in the agricultural

sector. (Why?)

countries are not likely to miss the message. Dictating that no family can have more

than two children is not politically palatable at this time. Such a dictum is seen as an

unethical infringement on the rights of those who are mentally, physically, and

monetarily equipped to care for larger families.

Yet the failure to control population growth can prove devastating to the

quality of life, particularly in high-population-growth, low-income countries.

One economist, Partha Dasgupta, describes the pernicious, self-perpetuating

process that can result:

Children are borne in poverty, and they are raised in poverty. A large proportion suffer

from undernourishment. They remain illiterate, and are often both stunted and

wasted. Undernourishment retards their cognitive (and often motor) development. . . .

What, then, is a democratic country to do? How can it gain control over

population growth while allowing individual families considerable flexibility in

choosing their family size?

Successful population control involves two components: (1) lowering the desired

family size, and (2) providing sufficient access to contraceptive methods and family

planning information to allow that size family to be realized.

The economic approach to population control indirectly controls population by

lowering the desired family size. This is accomplished by identifying those factors

that affect desired family size and changing those factors. To use the economic

approach, we need to know how fertility decision making is affected by the family’s

economic environment.

The major model attempting to assess the determinants of childbirth decision

making from an economic viewpoint is called the microeconomic theory of fertility.

The point of departure for this theory is viewing children as consumer durables.

The key insight is that the demand for children will be, as with more conventional

commodities, downward sloping. All other things being equal, the more expensive

children become, the fewer will be demanded.

With this point of departure, childbearing decisions can be modeled within a

traditional demand-and-supply framework (see Figure 21.6). We shall designate

the initial situation, before the imposition of any controls, as the point where

marginal benefit, designated by MB

1

, and marginal cost, designated by MC

1

,

are equal. The desired number of children at this point is q

1

. Note that, according

to the analysis, the desired number of children can be reduced either by an inward

shift of the marginal benefit curve to MB

2

, or an upward shift in the marginal cost

of children to MC

2

, or both. What would cause these functions to shift?

Let’s consider the demand curve. Why might it have shifted inward during the

demographic transition? Several sources of this change have emerged.

1. The shift from an agricultural to an industrial economy reduces the productivity

of children. In an agricultural economy, extra hands are useful, but in an industrial

economy, child labor laws result in children contributing substantially less to the

family. Therefore the investment demand for children is reduced.

2. In countries with primitive savings systems, one of the very few ways a person

can provide for old-age security is to have plenty of children to provide for

580 Chapter 21 Population and Development