The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BAKUFU FISCAL AND MANPOWER SUPPORTS 219

Once they reached the capital the guardsmen were mustered into

five groups (ban) headed by officers drawn from the Hosokawa,

Hatakeyama, Momonoi, and Odate houses. In the 1450s, guardsmen

administered holdings located in thirty-two of the forty-four provinces

of central Japan. These were concentrated in the central region,

stretching from Mikawa westward to Tango.

66

Interestingly, there

were virtually no placements in the closest of the home provinces,

such as Yamashiro, Iga, Yamato, very few in Harima, Settsu, Izumi,

Kawachi, or Kii, and none at all in Shikoku. The numbers of guards-

men varied over time and circumstances. Takauji is said to have em-

ployed 30; Yoshimitsu, 290; and Yoshinori, 180. Sato Shin'ichi esti-

mated that these numbers enabled the shogun to muster at a given

time between 2,000 and 3,000 mounted fighters.

67

All guardsmen were totally dependent on the shogun's favor for the

status they held in his service. Thus the guardsmen, like the adminis-

trators, comprised an element in the bakufu that was identified with

the well-being and continued existence of the Ashikaga house. Al-

though the guardsmen did not constitute a force capable of imposing

the shogun's will on even a single hostile shugo, in situations in which

there was a balance of power, they could swing that balance in the

shogun's favor or, as in the years of the Onin War, help maintain the

shogun's neutrality.

BAKUFU FISCAL AND MANPOWER SUPPORTS

Historians have sought to explain the economic foundations of the

Muromachi bakufu in terms of land and landed income. It is trouble-

some, therefore, not to be able to draw a clear picture of the bakufu's

landholdings that might account for the shogunate's fiscal operation.

It is on the basis of only a single document in the Kuramochi archives

that it is known that as of around 1300 the Ashikaga possessed some

thirty holdings

(gotyosho)

located in twelve widely scattered provinces.

Beyond this, there is almost no information on what happened to this

portfolio in subsequent years. No effort to document a continuous

analysis of Ashikaga landholdings has yet succeeded. This failure is

partially a result of insufficient diligence on the part of historians and

not on the absolute lack of documentation. In the last few years, for

66 Fukuda Toyohiko, "Muromachi bakufu hokdshu no kenkyu: sono jin'in to chiikiteki

bumpu," in Ogawa, ed.,

Muromachi

seiken,

p. 231.

67 Sato Shin'ichi, "Muromachi bakufu ron," in Iwanami koza Nikon

rekishi (chusei

2) (Tokyo:

Iwanami shoten, 1963), p. 22.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

220 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

instance, the number of identifiable Ashikaga holdings at the end of

the fourteenth century has risen from sixty to some two hundred, as

reported by Kuwayama Konen.

68

And the count is still rising. But

how these items came into existence, how they related to earlier hold-

ings,

and what their

fiscal

value was is not at all clear. All the evidence

so far has had to be extrapolated from documents that were not drafted

to answer such questions directly.

First, as a result of its defeat of the Hojo, the Ashikaga house's

estates were presumably augmented by a package of forty-five pieces

in twenty provinces given to Takauji and Tadayoshi by Godaigo. Re-

cent studies have confirmed the retention of a number of these hold-

ings into the 1390s, but not much beyond.

69

A list of sixty holdings

dating from shortly before the end of the fifteenth century does not

coincide with earlier lists. Clearly, there was a great deal of movement

in the bakufu's land base.

The latest scholarship suggests that the search for a "land base" to

explain the finances of the Ashikaga house has put its emphasis in the

wrong place.

70

The Ashikaga did not create, as did the Tokugawa

house, a large bloc of centrally administered lands from which reve-

nues were collected to benefit central bakufu storehouses. Rather, it

was the practice to assign landholdings to others to be administered on

behalf of the bakufu and also as a means of private support. By far the

greatest portion of the

goryosho

appears to have been allotted in this

way to members of the guards. Such grants tended to beccir.e heredi-

tary possessions. But up to the end of the regime, the close relation-

ship between the shogun and his provincial housemen guaranteed at

least some return to the shogun from this practice.

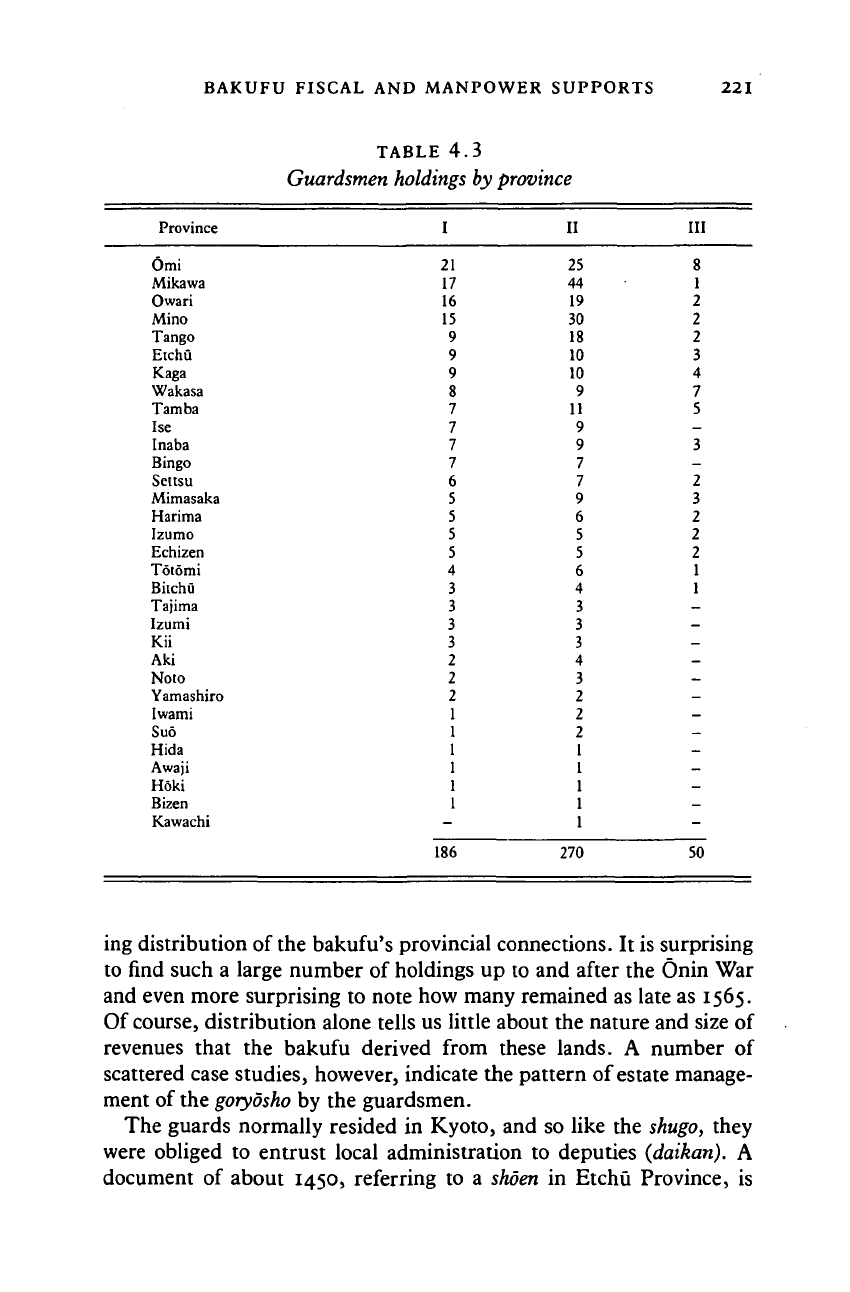

Fortunately, there are three sets of documents covering the activities

of the shogunal guards for the years 1444 to 1449, 1450 to 1455, and

1487 to 1489. Fukuda Toyohiko, in his careful study of these docu-

ments, concludes with the following table (Table 4.3), in which he lists

the number of guardsmen holdings, by province.

71

In this table he

offers two sets of figures based on the three sets of documents, Col-

umn I being a more conservative count than Column II. Column HI is

based on a roster of guards under Shogun Yoshiteru before his death in

1565 (see Maps 4.4 and 4.5).

The lists of guardsmen's holdings demonstrate graphically the shift-

68 Kuwayama Konen, "Muromachi bakufu keizai no kozo," in Nihon keizaishi taikei

(chusei

2)

(Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai, 1965), pp. 193-9. 69 Kuwayama, "Sosoki," p. 18.

70 Imatani, "Sengokuki," pp. 18-22; Kuwayama, "Keizai no kozo," pp. 219-20.

71 Fukuda, "Hokoshu," p. 231.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BAKUFU FISCAL AND MANPOWER SUPPORTS

221

TABLE 4.3

Guardsmen

holdings

by province

Province

Omi

Mikawa

Owari

Mino

Tango

Etchu

Kaga

Wakasa

Tamba

Ise

Inaba

Bingo

Settsu

Mimasaka

Harima

Izumo

Echizen

Totomi

Bitchu

Tajima

Izumi

Kii

Aki

Noto

Yamashiro

Iwami

Suo

Hida

Awaji

Hoki

Bizen

Kawachi

I

2

II

25

17 44

1(

3 19

15 30

9 18

9 10

9 10

i

$ 9

7 11

•

•

•

7 9

7 9

7 7

6 7

C

(

t

<

i

;

I

:

A

I

> 9

> 6

> 5

> 5

L 6

! 4

! 3

3

I 3

4

! 3

2 2

-

2

I 2

1

1

1

I 1

1

186 270

III

8

1

2

2

2

3

4

7

5

_

3

—

2

3

2

2

2

1

1

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

-

-

_

-

50

ing distribution of the bakufu's provincial connections. It is surprising

to find such a large number of holdings up to and after the Onin War

and even more surprising to note how many remained as late as 1565.

Of course, distribution alone tells us little about the nature and size of

revenues that the bakufu derived from these lands. A number of

scattered case studies, however, indicate the pattern of estate manage-

ment of the

goryosho

by the guardsmen.

The guards normally resided in Kyoto, and so like the shugo, they

were obliged to entrust local administration to deputies {daikan). A

document of about 1450, referring to a shoen in Etchu Province, is

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

222 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

typical.

72

Out of a total annual tax assessment of

780

kan,

340 kan

were

lost through poor harvest and the illegal encroachment of neighbors,

leaving 430 kan as the reduced tax base. Of

this,

one-fifth (86 kan) was

absorbed for managerial services by the guard and his agents, and

another one-fifth was spent in transportation fees, leaving three-fifths

(250 kan) for delivery to the bakufu. No claim can be made that a

hard-and-fast rule of one-fifth for the guardsmen and three-fifths for

the shogun was enforced. But clearly, besides guard duty the guards

were expected to facilitate the delivery of a tangible amount of income

to the bakufu. Because these holdings, as seen in Column III, tended

increasingly to cluster near the capital, the capacity of the Kyoto-

based guards to hold on to them and to derive income from them for

their own support and for that of the shogun was relatively high.

Yet another category of land that could benefit the shogun were

those that had been donated to patronized temples, like the Gozan.

Many properties that the shogun gave to temples as pious gestures

were in later years called on to help support the bakufu. In certain

locations it appears that members of the Zen monasteries'

fiscal

admin-

istrations, the

tohanshu,

served as managers of lands that were held in a

manner not unlike the regular

goryosho.

n

The fiscal base of the Muromachi bakufu was not limited to income

from the

goryosho.

A growing portion was derived as a consequence of

the shogun's authority to levy taxes on special groups and activities in

the city of Kyoto and the commercial community at large.

One feature of the Muromachi bakufu's fiscal structure was that

several bakufu agencies were supported by direct endowments in land

or in rights to income for specific services rendered. For example, as

the Administrative Council took over more of the burden of adminis-

tration in Kyoto, sources of support were sought within the city. In

turning to this "inner" source of income, the bakufu took advantage of

the urban commercial tax base that had been the historical preserve of

the civil and religious aristocracy. One of the main sources of such

income came from the categories of merchants known as

sakaya

(sake

brewers) and

doso

(storehouse keepers). The right of the capital police

to tax these organizations had been recognized for years on the basis

that those responsible for maintaining law and order in the city should

be supported by the recipients of this protection. The practice began

with the collection of special contributions for special events, such as

72 Morisue Yumiko, "Muromachi bakufu goryosho ni kansuru ichi kosatsu," in Ogawa, ed.,

Muromachi seiken, pp. 254-5. 73 Imatani, Sengokuki, pp. 11-60.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BAKUFU FISCAL AND MANPOWER SUPPORTS 223

imperial enthronement ceremonies or the rebuilding of temples and

palaces. A levy in 1371, to cover the enthronement expenses of Em-

peror Goenyu, imposed a payment of thirty kan per warehouse and

two hundred mon in cash per vat on the breweries. In 1393, having

taken over control of the city's administration, the bakufu made im-

posts of this kind a regular practice. The 1393 order issued from the

council refers to a figure of six thousand kan as the amount custom-

arily paid to the monks of the Enryakuji and states that this now

should come to the bakufu.

74

Kuwayama suggests an even closer relationship between the

mandokoro and the doso. The latter were at first not so much money-

lenders as storehouse keepers, whose fireproof storage houses were

used for safekeeping by the aristocracy. Later, as an extension of such

a service, doso began to serve as fiscal managers, extending credit on

the basis of stored goods. Doso also appear to have been appointed as

officials of the shogun's treasury (kubo mikura). Hence they became

both the objects of taxation and the means of tax collection.

75

The

bakufu in time developed a number of other commercial and transport

taxes derived from the patronage of merchant guilds, the establish-

ment of toll barriers on highways, and the sponsorship of foreign

trade. The importance of trade with Ming China to the political,

cultural, and economic life of Muromachi Japan has been dealt with

extensively elsewhere. It has been suggested that in addition to the

"enormous profits" derived from it, the trade gave to the bakufu

monopoly control over the Chinese coins imported into Japan and

thereby a status equivalent to that of a central mint.

76

But the various

benefits that accrued to the bakufu from this trade are still not wholly

understood.

Another complex area of bakufu and shogunal house income per-

tains to revenues derived from the shogun's aristocratic and military

status.

For instance, the shogun could count on the support of his

shugo

vassals for both military and nonmilitary assistance. For a given

military action, it was generally the responsibility of one or more shugo

to mobilize private forces on the shogun's

behalf.

Of course, this

meant the prospect of tangible reward if the action proved successful.

The 1441 Yamana attack on the Akamatsu referred to earlier is a case

74 Prescott B. Wintersteen, "The Early Muromachi Bakufu in Kyoto," in Hall and Mass, eds.,

Medieval Japan, pp. 208-9.

75 Kuwayama Konen, "Muromachi bakufu keizai kiko no ichi kosatsu, nosen-kata kubo okura

no kino to seiritsu," Shigaku zasshi 73 (September 1964). 9-17.

76 Takeo Tanaka, with Robert Sakai, "Japan's Relations with Overseas Countries," in Hall and

Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan in the Muromachi Age, p. 170.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

224

THE

MUROMACHI BAKUFU

in point. As a result of the successful campaign, Yamana was made

shugo

of two provinces vacated by the Akamatsu.

In the area of nonmilitary expeditions, the shogun had the right to

requisition from his

shugo

contributions for public works, such as the

building of shogunal residences. The 1437 requisition often thousand

kan for the shogun's residence was imposed differentially on

shugo

according to the number and size of the provinces that each held. The

impost was distributed among twenty-two

shugo

on the basis of two

hundred kan for those who held only one province and one thousand

kan for houses holding three or more. Other forms of contribution

from

shugo

were the standard practice that

shugo

build their residences

in Kyoto, that they maintain their own armed forces of from three

hundred to five hundred horsemen, and that when appointed to a

bakufu office, such as the Board of Retainers, they staff their offices

with their own men. One notable example is the case of Ashikaga.

Yoshimasa's project to build the Higashiyama villa, the central struc-

ture of which was the Silver Pavilion (Ginkaku). The actual fund

raising began in

1481,

only four years after the termination of the Onin

War. Yet

shugo

were dunned for contributions as part of their duty

toward the shogun. Despite the war-torn condition of the country, the

money was collected. As Kawai Masaharu writes, the shogun himself

was a person of charismatic prestige who could still expect support of

this kind even in the aftermath of

a

ten-year war that he himself had

brought on. It remained a matter of political value for an aspiring

provincial daimyo to contribute toward, or build

himself,

palaces for

the

tenno

or shogun in the capital.

77

Another source of income for the shogun resulted from his powers

of appointment. Among aristocratic circles it was standard practice for

those appointed to a high court or temple rank by the shogun to pay

him a gratuity. Imatani Akira estimates that the flow of treasure into

the bakufu coffers from this practice was a major source of support for

the bakufu, especially in its declining

years.

The income from appoint-

ments alone has been estimated at 3,600

kanmon

annually.

78

Of course,

this flow of wealth within elite circles was not all in one direction. The

shogun himself

was

obligated to give gifts and to contribute funds for

the building of palaces and temples and for the performance of various

rituals such as imperial enthronements and funerals. In such situations

the shogun was more apt to use his powers to require national compli-

77 Kawai Masaharu, Ashikaga

Yoshimasa

(Tokyo: Shimizu shoin, 1972), pp. 147-50.

78 Martin Collcutt, Five Mountains: The Rinzai Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981), pp. 235.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS 225

ance with bakufu requisitions rather than to draw funds himself from

the bakufu's stores.

79

Such requisitions generally took the form of a

provincewide tansen tax.

For much of the Muromachi period, tansen represented a major

source of income for the bakufu, to the point that the Administrative

Council (mandokoro) maintained an officer in charge of tansen reve-

nues.

The

hokoshu

were used as collecting agents in the provinces. The

picture that emerges, therefore, is one in which land, by being dis-

persed as private enfeoffments, served mainly to support the many

families and institutions that constituted the "governing establish-

ment." The resources that powered the actual functions of govern-

ment appear to have come from general taxes, like tansen, whose

collection depended on the continuing prestige of the Ashikaga house

as a charismatic entity within what essentially was a structure inher-

ited from the imperial bureaucracy.

THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS

The final century of Muromachi bakufu rule has given historians a

number of difficult interpretive problems. During these years the

bakufu was obviously in decline, and the shogun was increasingly

inconsequential as a political force. In fact, Japanese historians com-

monly divide the time from the outbreak of the Onin War in 1467 until

Oda Nobunaga's entrance into Kyoto in 1568, as the Sengoku period,

the era of warring provinces, thus shifting the main focus of their

attention from the capital and the shogun to the provinces where the

daimyo successors to the

shugo

fought among themselves for territorial

hegemony. But it is increasingly apparent that the ground swell of

change in Japanese government and society that took place in the years

following the Onin War should not be described simply in terms of

denouement or breakdown. The bakufu, as separate from the shogun

as person, did retain a function throughout the last hundred years.

And although these were times of instability, they gave rise to the

structures and institutions that were to support a new, and in many

ways revolutionary, centralized order.

80

Although the political and social order of the mid-Muromachi pe-

riod may have appeared to differ fundamentally from what it had been

79 Nagahara, "Zen-kindai," pp. 39-40.

80 Mitsuru Miyagawa, with Cornelius J. Kiley, "From Shoen to Chigyo: Proprietory Lordship

and the Structure of Local Power," in Hall and Toyoda, eds., Japan in the Muromachi Age,

pp.

89-105.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

226 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

at the end of the Kamakura era, the main premises on which Japanese

government rested remained basically unchanged. Despite the "en-

croachment of military government" on civil authority, the polity at

large, the

tenka,

was still conceived as before. The same touchstones of

legitimation were recognized, and authority was still regarded as a

legal right granted or justified from above.

But by the end of the fifteenth century, this order was being chal-

lenged by the appearance of groups or communities that sought, from

the higher central authority, autonomy in their local affairs. At the

upper level, this took the form of

"kokujin

lordships"

(zaichi ryoshu)

whereby local buke families became the sole proprietors of their own

lands,

managing to protect themselves from higher authority by their

own strength of arms or by the formation of leagues or compacts (ikki)

with neighboring

kokujin.

At first, these compacts were small in scale,

but as in the case of Aki Province, some were able to counter the

interference of both the bakufu and neighboring

shugo.

The revolution-

ary aspect of such compacts was that they were organized on the basis

of territory and were held together by mutual agreement for the pur-

pose of self-defense. By the end of the fifteenth century, local military

lords emerged out of the ranks of

kokujin,

many of them heads of ikki

leagues, whose territory

was

made large enough to give them the status

of daimyo. This, as Kawai has shown, was a major impetus for the

formation of the so-called

sengoku

daimyo.

81

Unlike the shugo daimyo whose legitimacy was derived from the

bakufu, the

sengoku

daimyo drew their primary authority from their

ability to exercise power and to maintain local control over the other

kokujin and peasant communities within their sphere of command.

They might on occasion, however, declare themselves successors to

shugo

or other provincial officials. But their main reliance, besides

their own military strength, was on their capacity to secure the loyalty

of their military followers and to convince the other inhabitants of

their territories of their ability, or at least intent, to work for the good

of the territorial community. This situation was reflected in the large

body of legal codes issued by

sengoku

daimyo, in which the daimyo

territory was conceived of as an organic entity,

a

kokka, over which the

daimyo exercised public authority

(kogi).*

2

81 Kawai, with Grossberg, "Shogun and Shugo," pp.

80-83.

82 Shizuo Katsumata, with Martin Collcutt, "The Development of Sengoku Law," in John

Whitney Hall, Keiji Nagahara, and Kozo Yamamura, eds., Japan Before Tokugawa: Political

Consolidation and Economic Growth, 1500-1650 (Princeton,

N.

J.: Princeton University Press,

i98l)>PP. "4-17-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS 227

The trend toward local autonomy was evident at the lower levels of

Japanese society as well, as the cultivator class underwent a major

transformation during the late Muromachi period.

83

One aspect of this

was the increased freedom won by agricultural villages to organize

their lives according to the community's desire. This was reflected in

the appearance of village assemblies (yoriai) and village-established

codes for internal regulation. It was reflected further in the success of

some communities in winning from higher authority the rights to

water use, autonomy of internal administration, and adjudication of

disputes. Some even earned the right of immunity from entrance by

officials of higher authority, as long as an agreed-upon annual tax was

delivered. Many of these concessions were won by the use of the only

weapons the villages possessed: the organization of village compacts

and mass demonstrations, both called ikki. It was in this context of

local unrest that the incipient daimyo of the Sengoku age recognized

the need to accommodate the demands of the peasantry and thus

declared themselves the protectors of all classes within their realms

(kokka).

By professing their regard for the common good, they

claimed the right to govern their territory on the strength of the sup-

port they received from those they governed. Thus they invoked a new

legitimacy, not derived from tenno or shogun, but established by the

implied consent of the public will. This was the making of a new

rationale for government, a radically new tenka.

8

*

Although these changes were taking place in the provinces, their full

impact did not reach the capital region until after the mid-sixteenth

century. The capital and the surrounding agricultural lands in the prov-

inces of Yamashiro, Omi, Kawachi, Settsu, and Yamato and a few other

locations made up a central region that retained its own configuration

throughout the last century of Ashikaga rule. And in this region in

which the economy and society were still dominated by the interests of

the court nobility and the central religious orders, the bakufu still had a

role to play. During the last century, though the bakufu may have lost its

ability to affect national affairs, it still was an important mechanism

through which the noble houses, the great temples, and the wealthy

merchant houses integrated their interests. Thus the bakufu continued

to adjudicate disputes and to issue decrees until 1579.

8s

83 Keiji Nagahara, with Kozo Yamamura, "Village Communities and Daimyo Power," in Hall

and Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan in

the Muromachi

Age, pp. 107-23.

84 Ibid., pp. 121-3.

85 Ashikaga legislation, as revealed in the supplementary orders (tsuikahd), increasingly nar-

rowed its scope to the capital city and its environs. See items 400-530 (1520-1570) in Kemmu

Shikimoku and

Tsuikaho,

pp. 145-64.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

228 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

The event that so dramatically started the downward slide of the

Muromachi bakufu was the "War of Onin and Bummei," (1467-77),

usually referred to simply as "Onin." A war that involved nearly all of

the

shugo

houses of central Japan, it was doubly destructive because it

was fought out in the streets of

Kyoto.

The issue that brought on the

war was a conflict between the Hosokawa and Yamana families over

the choice of heir to the shogun Yoshimasa. In the fighting, much of

central Kyoto and the northern fringe of the city was destroyed, and

many courtiers and priests fled the capital for the provinces. The

shogun Yoshimasa remained

aloof,

maintaining his usual standard of

aristocratic life.

If Yoshimitsu emerges in Muromachi history as the heroic model of

the noble military ruler, Yoshimasa is generally pictured as the tragic

ruler whose effete behavior brought on the declining fortunes of the

ruling house.

86

Yoshimasa, the second son of

the

murdered Yoshinori,

was named shogun in

1443

at the

age

of eight.

Being a

minor at the time,

he was placed under the guardianship of the kanrei, Hosokawa

Katsumoto. He was declared of

age

in 1449 and served as shogun until

1473,

when he retired in favor of his son Yoshihisa. He lived on until

1489.

In Yoshimasa's early

years

the bakufu had

still

not recovered from

the shock inflicted by the murder of the shogun in 1441. At the same

time,

the country as a whole was suffering from acute economic prob-

lems.

Rural mobs frequently broke into the capital, demanding relief

from debts and taxation and forcing the bakufu to issue debt cancella-

tion edicts

(tokusei-rei).

Widespread famine conditions during the 1450s

led to death by famine in parts of Japan. Yet Yoshimasa and

his kuge

and

buke

colleagues engaged in politics as usual, building costly residences

and bickering over court preferment and family inheritance. In 1458,

Yoshimasa rebuilt the shogunal palace at great expense.

Meanwhile, political tension among the

shugo

was building up to the

point of general warfare.

87

Yet during the

fighting

that started in 1467,

Yoshimasa built a special residential palace for his mother. He had

started in 1465 a retirement residence in the eastern foothills but had

dropped the project when war broke out in

Kyoto.

In

1482,

however, he

began in earnest to build the Higashiyama villa that was to contain his

monument, the Silver Pavilion (Ginkaku). In 1483, Yoshimasa moved

to Higashiyama where

he

lived out his life

as a

patron of the

arts,

setting

a style that was to leave an enduring mark on Japanese cultural history.

86 Kawai, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, offers the most complete modern biography.

87 Iikura Kiyotake, "Onin no ran iko ni okeru Muromachi bakufu no seisaku," Nihcnshi kenkyu

(1974).

139-5'•

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008