The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE MUROMACHI DISTRIBUTION OF POWER 209

ers to manage local affairs in his absence. Frequently, even the deputy

shugo was called to Kyoto, thus necessitating the appointment of a

subdeputy (shugo-matadai). As can be imagined, shugo residing in

Kyoto found it difficulty to develop a reliable chain of command

between capital and province. Vassal

shugo-dai

could play a critical role

in either expanding and safeguarding the shugo's local authority or

undermining it. The problem was especially acute in situations in

which the shugo were exercising jurisdiction over an unfamiliar prov-

ince.

In such cases, the

shugo

were often forced to depend on the head

of a prominent local family, a kokujin, to serve as deputy. In many

cases,

these families eventually turned against their Kyoto-based supe-

riors so as to grasp local military hegemony.

46

Contact between shugo and shogun was at first personal and direct.

But with the adoption of the kanrei system, the shogun's relations with

the

shugo

were mediated through the kanrei, and certain decisions were

made subject to the assembly of senior

shugo.

There was, of course, an

inherent contradiction in a procedure that put the deputy and the

assembly between the shogun and his vassal shugo. A strong-minded

shogun, like the mature Yoshimitsu or Yoshinori, resented the restric-

tions this imposed on his freedom of command. The kanrei-yoriai

system as a check on shogunal absolutism worked well up through the

time of Yoshikazu, the fifth shogun. And even the sixth shogun, the

strong-willed Yoshinori, was forced to accept from time to time the

collective will of the kanrei and yoriai.

The third shogun, Yoshimitsu, had brought the status and power of

the office to its highest level. Yet his grandiose behavior and autocratic

rule were tolerated, even admired, by the shugo, who were themselves

caught up in the heady experiences of aristocratic life in Kyoto.

Yoshimitsu's two successors retreated from this autocratic posture and

acknowledged a greater acceptance of the kanrei-yoriai system.

Yoshikazu, living with the knowledge that his father, Yoshimitsu, had

intended to pass over him as his heir, was not inclined to offer personal

leadership to the bakufu, and so died without naming his own succes-

sor. As a result, his successor was determined by lot by the Ashikaga

family council, and Yoshinori, Yoshimitsu's sixth son, was chosen.

Yoshinori was at the time a mature man of thirty-four. Early in his life,

with no apparent hope of becoming shogun, he had entered the priest-

hood, and at the time he was named shogun he was serving as chief

abbot (zasu) of the Enryakuji and head of the Tendai sect on Mount

46 Hall,

Government

and Local

Power,

pp. 227-33.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

210 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

Hiei. He immediately showed himself to be a leader who intended to

become personally involved in bakufu affairs. He was

a

good politician

and was determined to increase the power of

the

Ashikaga house.

Yoshinori's first move was to change bakufu administrative proce-

dures by reorganizing the Corps of Administrators

(bugyonin-shu)

and

instituting what was called the shogunal hearing

(gozen-sata).

47

Under

this procedure, briefs on policy matters were prepared by the adminis-

trators and brought directly to the shogun for decision. This meant

that in most instances the

kanrei

was not consulted, as evidenced by

the appearance of

bugyonin

directives that expressed the shogun's will

without the customary countersignature of the

kanrei.

This change

was correctly perceived as a move toward greater shogunal personal

rule.

48

Another line of action that Yoshinori pursued proved even more

disquieting, for it involved the shogun's effort at directly interfering in

shugo

domestic affairs. Using his authority to approve

shugo

appoint-

ments and inheritances, Yoshinori began to manipulate the lines of

succession among

shugo

houses so as to bring to Kyoto

shugo

more

amenable to his direction.

49

One device in particular available to

Yoshinori was his authority to enlist the lesser members of

shugo

houses into his private military force as guardsmen. Such appoint-

ments were usually of second or third sons in

shugo

families, men not

normally in line for the family headship. But as a result of

the

personal

relationship between shogun and guardsmen, the shogun was able to

intervene on behalf of those he favored to ensure their succession.

This was the motivation for a series of seemingly arbitrary actions

taken by Yoshinori that came to a head in 1441. In that year, the

shogun appeared to be taking steps to block the appointment of

Akamatsu Mitsusuke's chosen heir to the post of

shugo

in Harima and

Bizen. It was to forestall this move that Mitsusuke killed Yoshinori

while the shogun was being entertained in the Akamatsu residence in

Kyoto. This incident, known as the Kakitsu affair, marks a turning

point in Muromachi bakufu history. That a prominent

shugo

could

murder the shogun who was a guest in his own house was disquieting

enough but that the murderer could survive the incident and return to

his provincial base without suffering an immediate punitive attack

47 Kuwayama, with Hall, "Bugyonin," in Hall and Toyoda, eds., Japan in

the Muromachi

Age,

pp.

58-61.

Tsuikaho numbered 183, 184, 189, and 190 to 197 issued in 1428 dealt with this

issue.

48 Imatani Akira, Sengokuki

no Muromachi bakufu no

seikaku,

vol. 12 (Tokyo: Kadokawa shoten,

1975)5 PP- 154-6- 49 Arnesen, Ouchi

Family's

Rule, p. 187.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU 211

implies that there were strong feelings of sympathy for the Akamatsu

leader's actions.

50

Mitsusuke, however, was finally chastized. Having

fortified himself in his provincial headquarters, he fought to the finish

against a shogunal army led by the Yamana, the

shugo

of several nearby

provinces. The Yamana invasion was not in reluctant compliance with

bakufu orders, for the Yamana had long coveted the Akamatsu prov-

inces of Mimasaka, Bizen, and Harima. As expected, the Yamana

received these provinces as a reward for Mitsusuke's destruction.

The Kakitsu incident brought an end to a brief period of what some

have called "shogunal despotism." But the weakening of shogunal

power did not lead to a return to kanrei-shugo council ascendancy

either. As a result of Yoshinori's meddling, one of the three kanrei

houses, the Shiba, was greatly weakened, and the house served as

kanrei only once in the ensuing years. In the aftermath of the Kakitsu

incident, competition over the post of kanrei was largely confined to

the Hosokawa and Hatakeyama houses. Moreover, the nature of the

post itself changed. After 1441, the post of kanrei carried little of its

former responsibility of supporting the shogun and mediating with the

shugo.

Rather, the post was regarded as a means to exercise private

influence over the bakufu. Because such influence could result in

tangible benefits to both the kanrei and his favored

shugo,

there was a

tendency for the shugo houses to divide into factions behind the two

remaining kanrei houses. How this situation led to the weakening of

the bakufu power base became clear during the time of Yoshimasa, the

eighth shogun. But before I turn to the events of this period, I shall

discuss in more detail the bakufu rule.

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU: INSTRUMENTS OF

ADMINISTRATION AND ENFORCEMENT

The Kemmu shikimoku, by announcing the Ashikaga's intent to follow

in the footsteps of the previous regime, implicitly laid claim to what-

ever powers that had accrued to the post of shogun under the Ho jo

regents. By 1350, the Ashikaga government had assumed a reasonably

stable form in which many of the organs of administration bore the

same names as used by the Kamakura shogunate. But identity in name

did not necessarily mean identity in function. The Ashikaga leaders

approached quite pragmatically the task of building a bakufu.

50 Sugiyama Hiroshi, "Shugo ryogokusei no tenkai," in Iwanami koza Nihon rekishi (chusei 3)

(Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1963), pp. 109-69.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

212

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

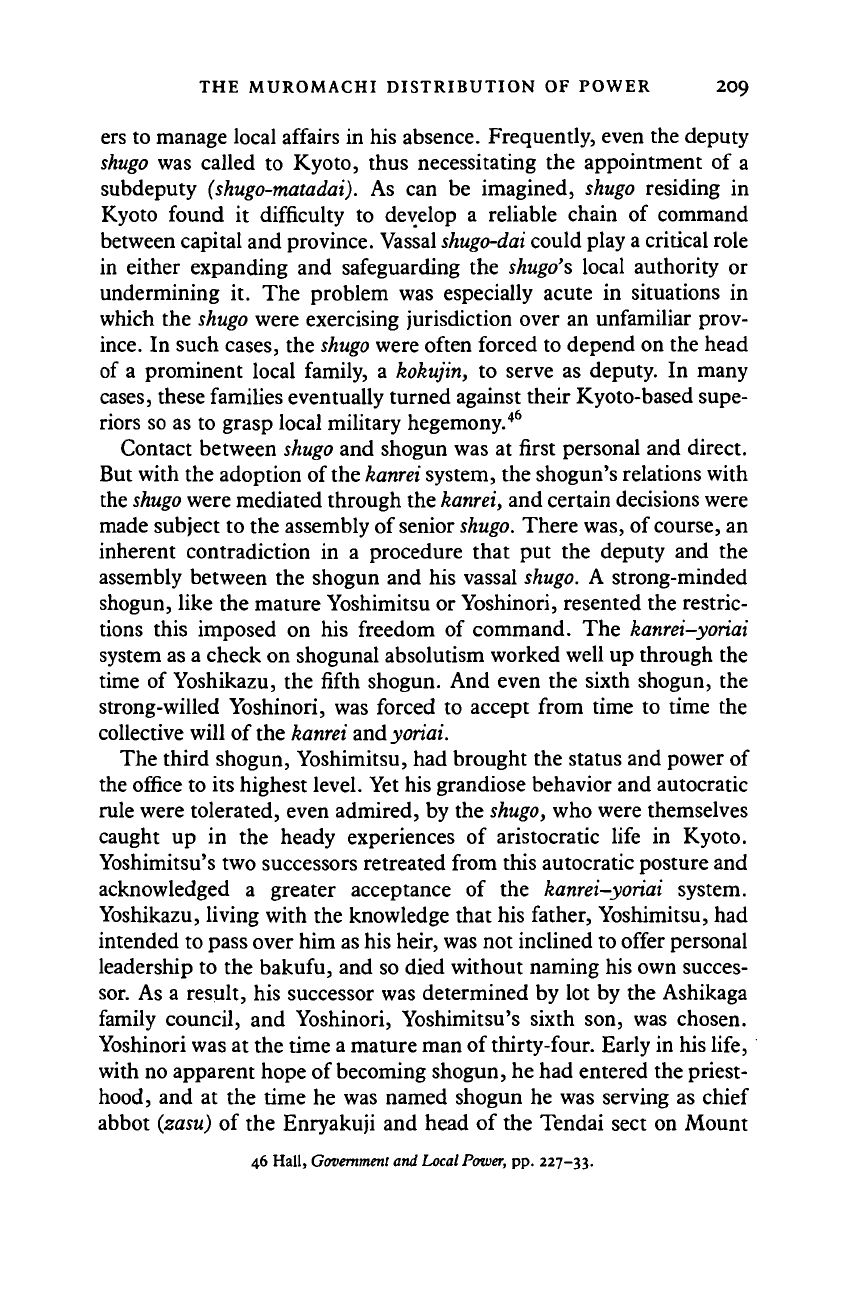

Takauji

•

(shogun)

- shitsuji

-

(manager)

Tadayoshi

'

• hyojo

•

samurai dokoro

(board

of

retainers)

onshokata

(office

of

rewards)

• andokata

(office

of

land titles)

"—

hikitsukekata

(office

of

adjudicants)

• zenritsu-kata

(commissioner

for Zen

and Ritsu monasteries)

- kantobugyo

(office

of

court

appointments)

- monchujo

(office

of

records)

Figure 4.2 Organization

of

the bakufu, 1350. (Solid horizontal line

indicates formal authority relationship; solid vertical line, a more

or

less equal formal status;

and

dashed line,

an

informal equality

or

division of authority.)

As

of

1350, when Tadayoshi

was

still working closely with

his

brother, the organization

of

the bakufu followed the form outlined

in

Figure 4-2.

5

' Sato Shin'ichi

has

emphasized

the

importance

of the

division

of

responsibility that

had

been worked

out by the

Ashikaga

brothers.

52

Takauji, the elder brother, as shogun and head

of

the

buke

estate, assumed the direction

of

the bakufu organs dealing with such

functions

as the

appointments

to

military posts,

the

distribution

of

rewards for military service, the enlistment of vassal followers, and the

management

of

Ashikaga lands. Sato described these powers

as

basi-

cally feudal. By contrast, Tadayoshi was

in

charge of what Sato called

the more "bureaucratic,"

or

administrative and judicial, functions of

government. Under Tadayoshi was organized the deliberative council,

consisting

of

selected professional bureaucrats,

and a

number

of of-

fices that kept land records, adjudicated lawsuits,

and

handled rela-

tions between

the

bakufu

and the

imperial court

and the

religious

orders.

51 Imatani, Sengokuki, pp. 151-81. 52 Sato, "Kaisoki," pp. 472-86.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

213

kanrei

-- —- —- —- —-

—

-

shugo yoriai

—- —- ——

shugo

(deputy) (council

of

shugo)

• samurai-dokoro

(board

of

retainers)

•

hikitsukeshu

(office

of

adjudicants)

shogun

————

I

hokoshu

(shogunal guards)

• mandokoro

(board

of

administration)

• monchu/o

(records office)

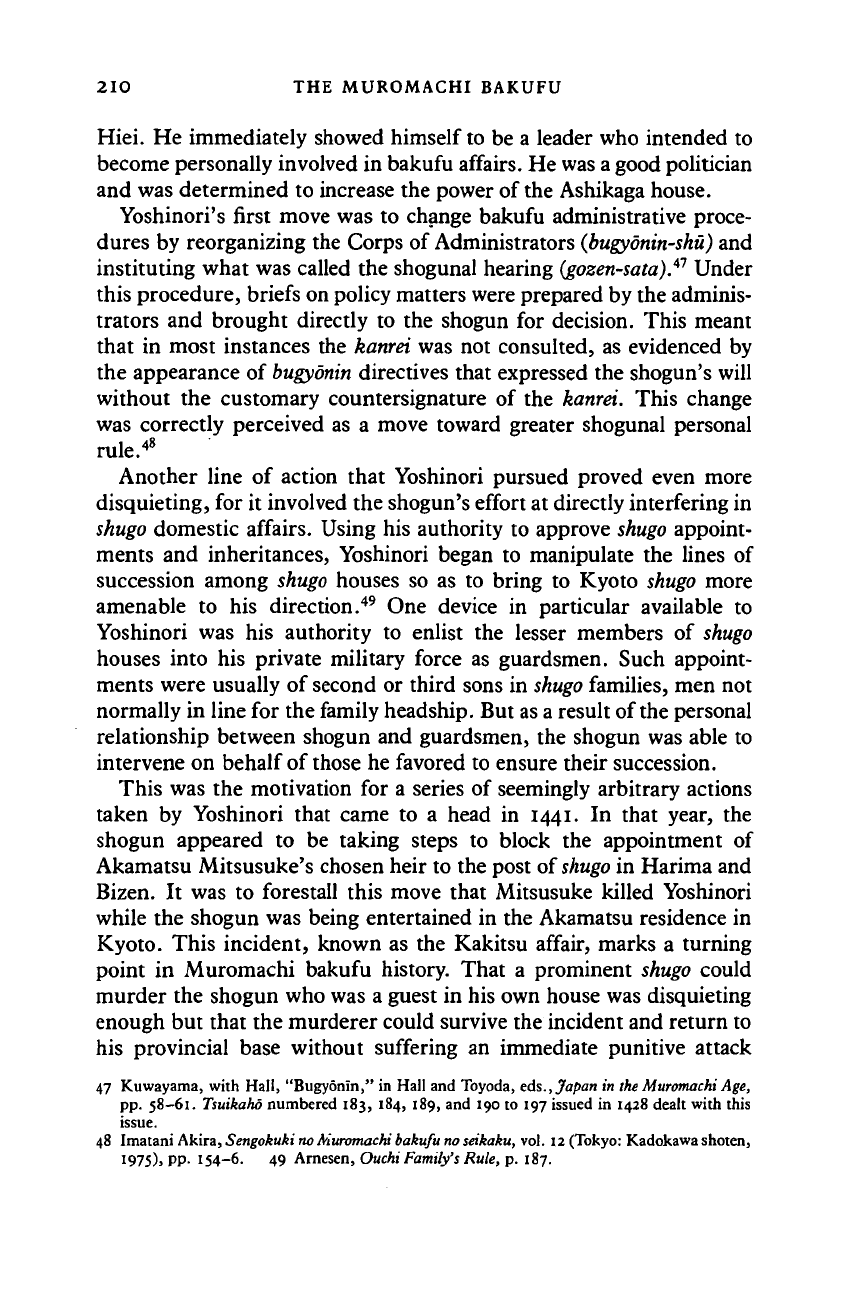

Figure 4.3 Changes

in

bakufu structure after Tadayoshi's expulsion,

1352.

(Lines same

as

in

Figure 4.2; double dashed line indicates

an

informal authority relationship.)

With Tadayoshi's expulsion from Kyoto

in

1352,

the

bakufu struc-

ture underwent

a

significant change, and many

of

the offices inherited

from Kamakura were either abolished

or

drastically modified

in

func-

tion. The most important such change,

as

seen

in

Figure 4.3, was

the

conversion

of

the

office

of

shitsuji

(the

bakufu's chief

of

operations)

into that of

kanrei

(deputy shogun)

and

the creation

of

the

shugo

coun-

cil (shugo yoriai).

53

The top

of

the Muromachi shogunal government was characterized

by both

a

greater direct involvement

in the

affairs

of

state

by the

shogun

and

a

more influential participation

by

the

shugo

houses

in the

decision-making process and

in the

bakufu administration.

The main bakufu offices with specialized functions were

the

Board

of Retainers

(samurai-dokoro),

the

Office

of

Adjudicants (hikitsuke-

shu),

the

Board

of

Administration

(mandokoro),

and

the Office

of

Rec-

ords

(monchujo).

Of

these,

at

the outset the Board of Retainers was

the

most important.

It

alone was headed by a major

shugo

house. Charged

with controlling

the

shogun's direct retainers,

the

Board

of

Retainers

was made responsible

for

securing

the

capital area from lawlessness

and administering the home province of Yamashiro. With the establish-

ment

of

the office of

kanrei,

the

samurai-dokoro

lost much of

its

powers

of control over

the

shogun's household retainers

and

over

the

shugo

houses. But its administrative and judicial functions

in

the capital area

continued to expand. The board,

for

instance, took over the powers of

the Imperial Capital Police

(kebiishi)

and

became

the

main police

and

53 Sato, with Hall, "Muromachi Bakufu Administration," in Hall and Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan

in

the

Muromachi

Age, pp. 47-49.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

214

THE

MUROMACHI 3AKUFU

judicial authority

in

Kyoto.

54

In

1385, moreover,

the

chief

(shoshi)

of

the Board

of

Retainers was given

the

added duty

of

serving as

shugo

of

Yamashiro Province.

It

became customary

to

rotate this assignment

among four major

shugo

houses:

the

Yamana, Isshiki, Akamatsu,

and

Kyogoku.

The actual day-to-day running

of the

Board

of

Retainers

was

dele-

gated

to a

deputy chief

(shoshidai),

appointed

by the

chief from among

his

own

private retainers. Hence

the

identity

of the

deputy changed

according

to who

served

as chief. As a

bureaucratic entity,

the

board

was given

a

certain stability

and

continuity

of

operation

by its

perma-

nent administrative

staff, a

group

of

individuals composed indepen-

dently

of the

chief

and his

deputy, drawn from

a

class

of

hereditary

administrators

or

professional bureaucrats, which will

be

described

later.

Despite

the

many important functions

of the

Board

of

Retainers,

after

the

Onin

War

(1467-77),

it

lost

its

central importance

to the

Administrative Council.

55

At

first

the

council

was

almost exclusively

concerned with

the

shogun's household

and its

fiscal management.

56

Its first chief officer was

a

hereditary administrator carried over from

the Kamakura bakufu,

a

member

of

the Nikaido house.

In

1379,

the

Nikaido were replaced

by the Ise

family,

a

line

of

hereditary retainers

who,

among other duties,

had

traditionally served

as

guardians

of the

Ashikaga shogun's heirs.

The

council came into

its own as the

bakufu's main administrative office when

the

shogun Yoshinori

be-

gan

to use it as the

organ through which

to

bypass

the

kanrei.

As the

sphere

of

shogunal government narrowed, however, this single

agency

was

able

to

handle nearly

all of

the shogunate's administrative

functions. Moreover, as the shogun found fewer

and

fewer opportuni-

ties

to

assert political initiative, procedures

in the

bakufu became

increasingly routinized under what Kuwayama Konen

has

called

the

"bugyonin

system."

57

Throughout

the

Muromachi period there were more than fifty fami-

lies

of

professional administrators available

for

service, many of whom

had served

the

imperial court

and the

Kamakura bakufu. Such fami-

lies were

now

brought into Ashikaga service because

of

their special

54 Haga Norihiko, "Muromachi bakufu samurai dokoro ko,"

in

Ogawa,

ed.,

Muromachi seiken,

PP-

25-55-

55 Imatani, Sengokuki,

p. 165. 56

Haga, "Samurai dokoro,"

p. 50.

57 Kuwayama, with Hall, "Bugyonin,"

in

Hall

and

Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan

in

the Muromachi

Age,

PP-

53-54-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU 215

administrative skills. In time they formed the Corps of Administra-

tors,

the

bugyonin-shu.

At any one time, between fifteen and sixty

members might be assigned to the finance, justice, and administrative

organs of

the

bakufu.

58

A study of

the

fluctuating

numbers of adminis-

trators retained by the Muromachi bakufu shows that in the period

before the Onin War, the numbers reflected the shifting balance of

power between the kanrei-yoriai system and the shoguns' effort to

exert their own influence on the bakufu. Thus the fewest numbers

were in evidence under Yoshimitsu, Yoshikatsu, and Yoshimochi, all

of whom followed the

kanrei

principle.

59

Yoshinori's efforts to exert his

direct shogunal prerogative was reflected by an immediate increase in

the size of the corps. This upward trend continued until Yoshimasa's

death. Thereafter, the number of members declined, to remain at

around fifteen until the end of the Muromachi bakufu. Members of

the corps were drawn from the following eleven families: Iio, Suga,

Saito,

Jibu, Eno, Sei, Nakazawa, Fuse, Matsuda, Yano, and Ida.

The drop in staff numbers reflected, first of

all,

a loss of power by

the Ashikaga house and also a change in function. Perhaps because of

the shogun's weakening power, the administrators increasingly be-

came an entrenched and self-perpetuating group of families that, more

than any other single factor, accounted for the continued existence of

the bakufu during its last hundred years. These families became the

agents through which members of the capital elite establishment dealt

with one another. For instance, administrators serving as members of

the Office of Adjudicants were assigned specifically to handle the

affairs of important shrines like the Iwashimizu Hachiman Gu or

Tsurugaoka Hachiman Gu, and great temples like the Enryakuji,

Todaiji, Kofukuji, Toji, and Tenryuji. In other words, these heredi-

tary administrators had begun to serve as agents of these institutions in

case of litigation before the council, receiving retainer fees for serving

as their spokesmen.

60

This was obviously a profitable arrangement. To

keep it alive, it was to the advantage of all concerned to maintain the

prestige of the shogun and the efficacy of the bakufu's remaining

organs of adjudication. That this happened is revealed by the fact that

the Ashikaga's supplementary laws continued to be issued into the

58 Haga, "Samurai dokoro," p. 27; Kuwayama, with Hall, "Bugyonin," in Hall and Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan in the Muromachi Age, pp. 56-60.

59 Kenneth A. Grossberg, "Bakufu and Bugyonin: The Size of the House Bureaucracy in

Muromachi Japan," Journal of Asian Studies 35 (August 1976): 651-4.

60 Kuwayama, with Hall, "Bugyonin," in Hall and Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan in theMuronmachi Age,

p.

62.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2l6 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

15 70s and that there are many records

of

action taken by the Office of

Adjudicants

in

the last decades of the Ashikaga regime.

61

But

to say

that

the

Muromachi bakufu continued

to

function until

the mid-sixteenth century

is

also

to say

that

the

scope

of

its compe-

tence narrowed.

By the

time

of the

last shogun,

the

scope

of the

bakufu's control

had

been reduced almost solely

to

the city

of

Kyoto

and

its

close environs. Control

of

Kyoto,

in and of

itself,

was an

important achievement,

and the

fact that Kyoto became subject

to

bakufu administration

was of

major significance

for the

Ashikaga

house's staying ability.

At the time the Ashikaga established their bakufu in Kyoto, the city

was still under the control

of

the civil and religious nobility. Takauji's

claim

of

chieftainship

of

the military estate gave him the authority

to

exercise military, judicial, fiscal,

and

appointment powers over

bushi

but not over the civil elite. The organs

of

imperial administration that

had been revived

by

Godaigo were soon

in

disarray. Yet the establish-

ment of the Muromachi bakufu did not automatically rectify the situa-

tion.

In Kyoto the imperial house,

the

high court nobility,

and

the great

religious institutions remained free

to

govern, through their

own

house staffs, their estates

and

other dependent groups like

the

mer-

chant and craft guilds.

In

fact, these groups and organizations can

be

conceived

of as a

distinct power structure with remarkable staying

power,

to

which modern historians have applied

the

term

kenmor,

seika.

62

Essential

to

this condition

was the

maintenance

of a

secure

capital area,

a

functioning judicial process,

and a

reasonably effective

machinery

for the

delivery

of tax

payments.

The

chief instruments

available

for

this were

the

Imperial Capital Police

(kebiishi)

and the

various management systems maintained

by the

Kyoto-based head-

quarters

(honjo)

of

the major civil and religious proprietary interests.

In its early policy,

the

bakufu sought only to assist

in

maintaining law

and order

in

the capital,

in

order

to

protect the provincial interests of

the most important civil and religious proprietors. Kyoto was adminis-

tered under what was essentially a dual polity.

63

61 Kuwayama Konen, Muromachi bakufu hikilsuke shiryo shitsei,

vol. 1

(Tokyo: Kondo

shuppansha, 1980).

62 This concept, most closely associated with Kuroda Toshio,

is

best described

in

English

by

Suzanne Gay

in

"Muromachi Bakufu Rule in Kyoto: Administration and Judicial Aspects"

in

Mass and Hauser, eds., Bakufu

in Japanese

History,

pp.

60-65.

63 Prescott

B.

Wintersteen, "The Early Muromachi Bakufu

in

Kyoto,"

in

Hall and Mass, eds.,

Medieval Japan,

p. 202.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU 217

Tension between the bakufu's Board of Retainers and the capital

police was quick to develop, especially in matters of conflicting juris-

diction. The failure of the court-maintained police to carry out their

duties effectively induced the bakufu to claim the need to increase its

police role in the capital. And the court was inclined to agree. A court

decree of 1370, noting the capital police's ineffectiveness in curbing

violence against the nobility by religious bill collectors, invited the

bakufu to provide assistance. Once the bakufu began enforcing the

court decrees, it began also to move into the court's economic affairs.

By decree in 1393 the bakufu took over the collection of dues from

brewers and moneylenders.

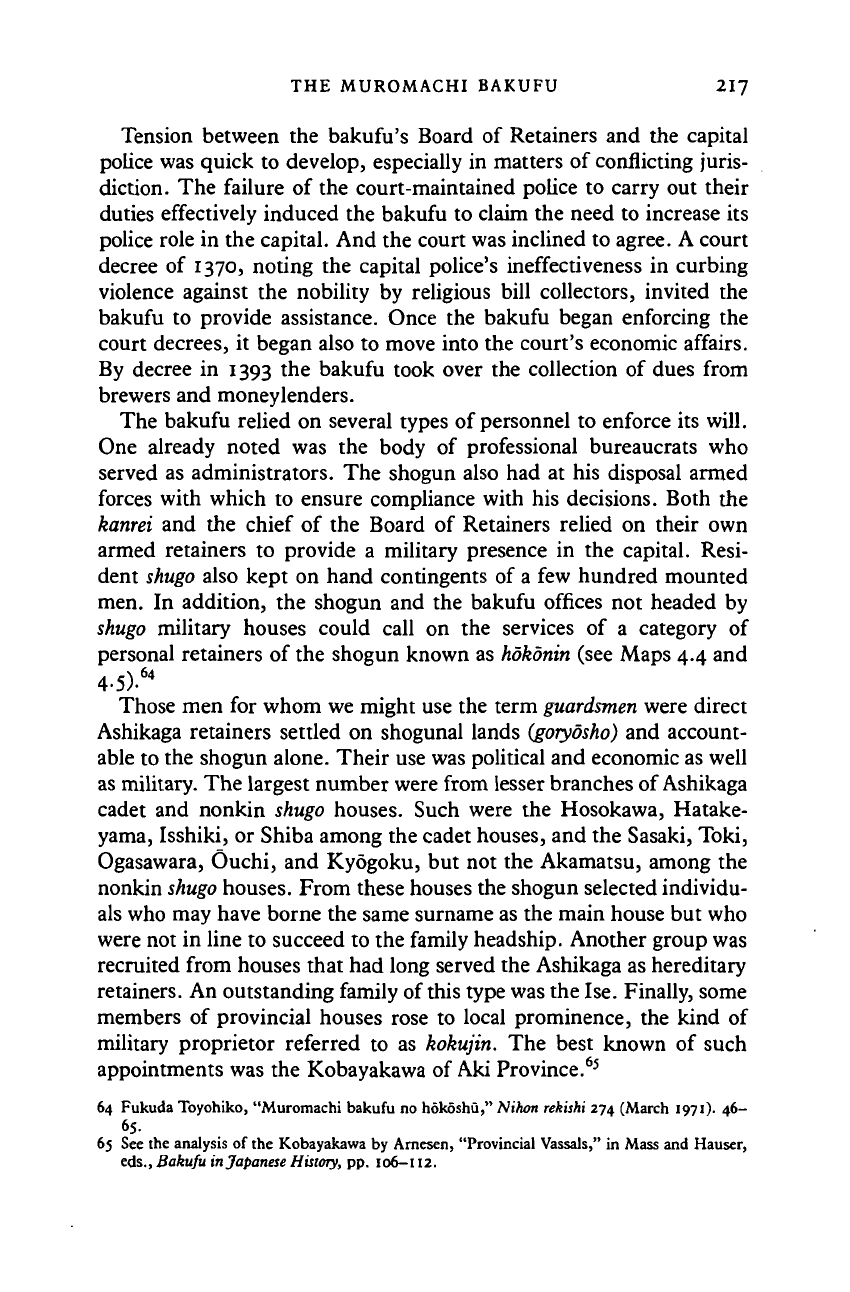

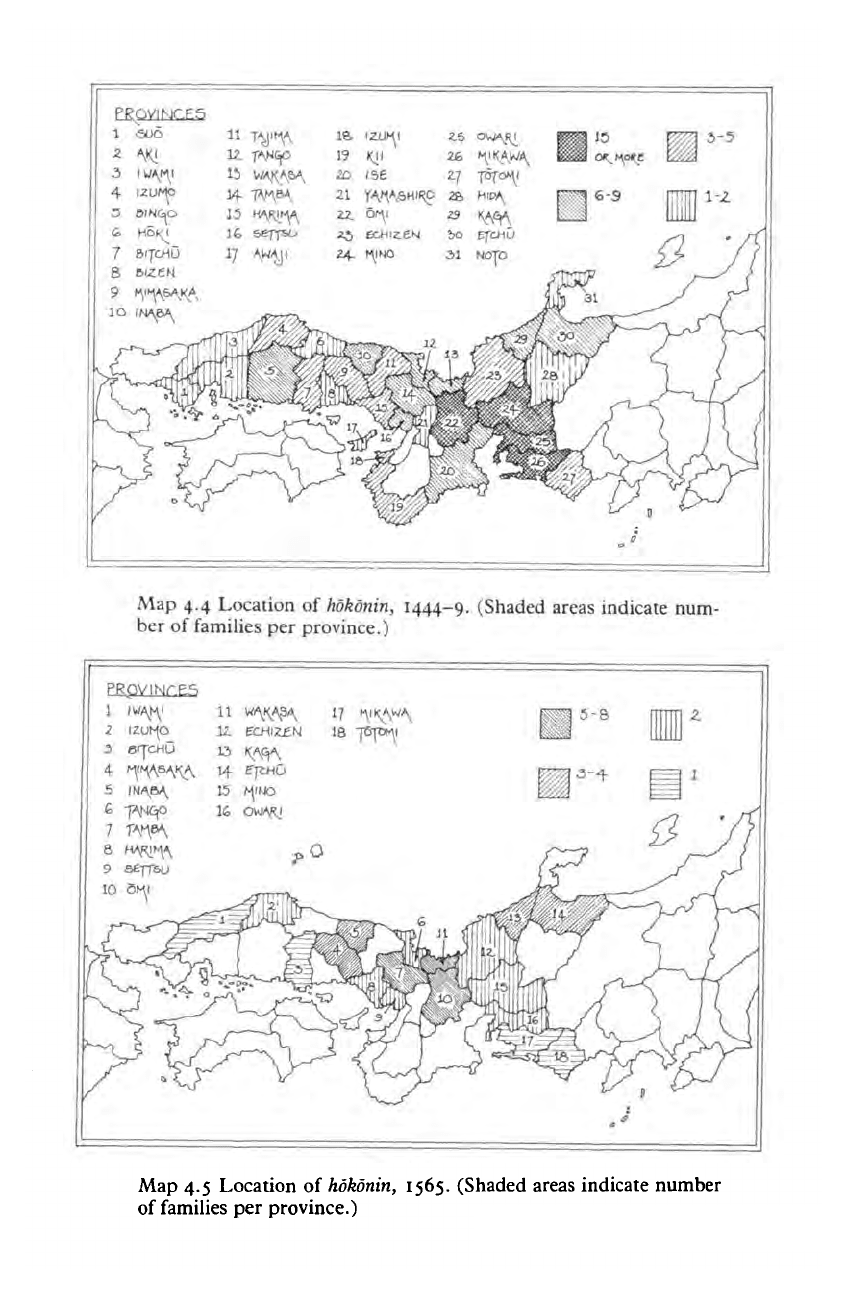

The bakufu relied on several types of personnel to enforce its will.

One already noted was the body of professional bureaucrats who

served as administrators. The shogun also had at his disposal armed

forces with which to ensure compliance with his decisions. Both the

kanrei and the chief of the Board of Retainers relied on their own

armed retainers to provide a military presence in the capital. Resi-

dent shugo also kept on hand contingents of a few hundred mounted

men. In addition, the shogun and the bakufu offices not headed by

shugo military houses could call on the services of a category of

personal retainers of the shogun known as hokonin (see Maps 4.4 and

4-5)-

64

Those men for whom we might use the term

guardsmen

were direct

Ashikaga retainers settled on shogunal lands

(goryosho)

and account-

able to the shogun alone. Their use was political and economic as well

as military. The largest number were from lesser branches of Ashikaga

cadet and nonkin shugo houses. Such were the Hosokawa, Hatake-

yama, Isshiki, or Shiba among the cadet houses, and the Sasaki, Toki,

Ogasawara, Ouchi, and Kyogoku, but not the Akamatsu, among the

nonkin

shugo

houses. From these houses the shogun selected individu-

als who may have borne the same surname as the main house but who

were not in line to succeed to the family headship. Another group was

recruited from houses that had long served the Ashikaga as hereditary

retainers. An outstanding family of this type was the Ise. Finally, some

members of provincial houses rose to local prominence, the kind of

military proprietor referred to as kokujin. The best known of such

appointments was the Kobayakawa of Aki Province.

65

64 Fukuda Toyohiko, "Muromachi bakufu no hokoshu," Nihon rekishi 274 (March 1971). 46-

65.

65 See the analysis of the Kobayakawa by Arnesen, "Provincial Vassals," in Mass and Hauser,

eds.,

Bakufu

in

Japanese History, pp. 106-112.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Map 4.4 Location of hokonin, 1444—9. (Shaded areas indicate num-

ber of families per province.)

PROVINCES

1

Z

3

4-

5

G

7

S

9

10

t

(S

^V

/

/

IZUMO

erp-iu

SEJT6U

OM,

11 M\\

13 KAp,'

14-

ejch

15 ^INC

16 OVMf

^-v-^

r

\5/\

17 f\l^\W/^

2£N 16 TCTOMI

\

>

5-8

-3-4

Wi

\A

I?

J

:

z

— 1

?

-/f

s /

Map 4.5 Location of hokonin, 1565. (Shaded areas indicate number

of families per province.)

f

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008