The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE ANNIHILATION OF CHIN 261

actions against Sung and therefore tried to negotiate for peace with the

Mongols. In 1220 the minister Wu-ku-sun Chung-tuan was sent on an

embassy to Chinggis khan, who was encamped at that time in Transoxania,

and offered to recognize the Mongolian khan as his elder brother in return for

a cessation of hostilities. This attempt to include the Mongolian ruler into

the network of pseudofamilial relations that had existed among the states of

continental East Asia since the tenth and eleventh centuries failed. A second

embassy of the Jurchen grandee was equally unsuccessful. This time,

Chinggis khan recommended to the Chin representative that Hsiian-tsung

renounce his imperial rank and instead become king of Honan (Ho-nan

wang) under Mongolian suzerainty. Chin, however, rejected the offer to be

invested with an inferior rank by the Mongols, and the peace talks therefore

came to an end in 1222.

In 1223 Hsiian-tsung died and his third son, Ning-chia-su (b. 1198;

Chinese names Shou-li and Shou-hsii; r. 1223-34) succeeded him. He was

the last ruler of Chin and was later canonized as Ai-tsung, "Pitiable Ances-

tor.

"

The ten years of his rule saw the final collapse of the Chin state and

Jurchen rule. When Ai-tsung assumed the throne, his government had lost

control over practically all the territories north of the Yellow River. Apart

from Honan, the former empire of Chin consisted only of parts of Shantung

and Shansi and the province of Shensi.

After Mukhali's death, the Mongolian attacks and raids lost some of their

previous vigor while Chinggis khan himself

was

engaged in the west. One of

Ai-tsung's first actions was to make peace with Sung (1224). Chin formally

gave up the claim to the annual payments, and Sung agreed to a cession of

hostilities. The ceremonial embassies for the New Year and the rulers' birth-

days were discontinued. This meant the end of the normal diplomatic inter-

course that had governed Sung-Chin relations for almost a century with

occasional interruptions (1160-5

an

d 1206-8). With regard to Hsi-hsia, Ai-

tsung favored reconciliation after

a

period of constant border warfare, military

actions that had sometimes been carried out with the Mongols' assistance. In

1224,

negotiations with Hsi Hsia were initiated, and in the ninth month of

1225 a peace treaty was concluded. The Hsia ruler was acknowledged as the

younger brother of

the

Chin emperor; both states also agreed to use their own

reign titles in diplomatic correspondence, which resulted in a rise in status for

Hsi Hsia because they were no longer considered to be vassals of Chin. The

border trade was also resumed, a vital matter for the Chin because their

cavalry had to rely largely on the import of Tangut horses now that the

grazing grounds of Manchuria had been lost to them. The willingness of the

Tanguts to cease their incursions into Chin territory on the Shensi border was

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

262

THE CHIN DYNASTY

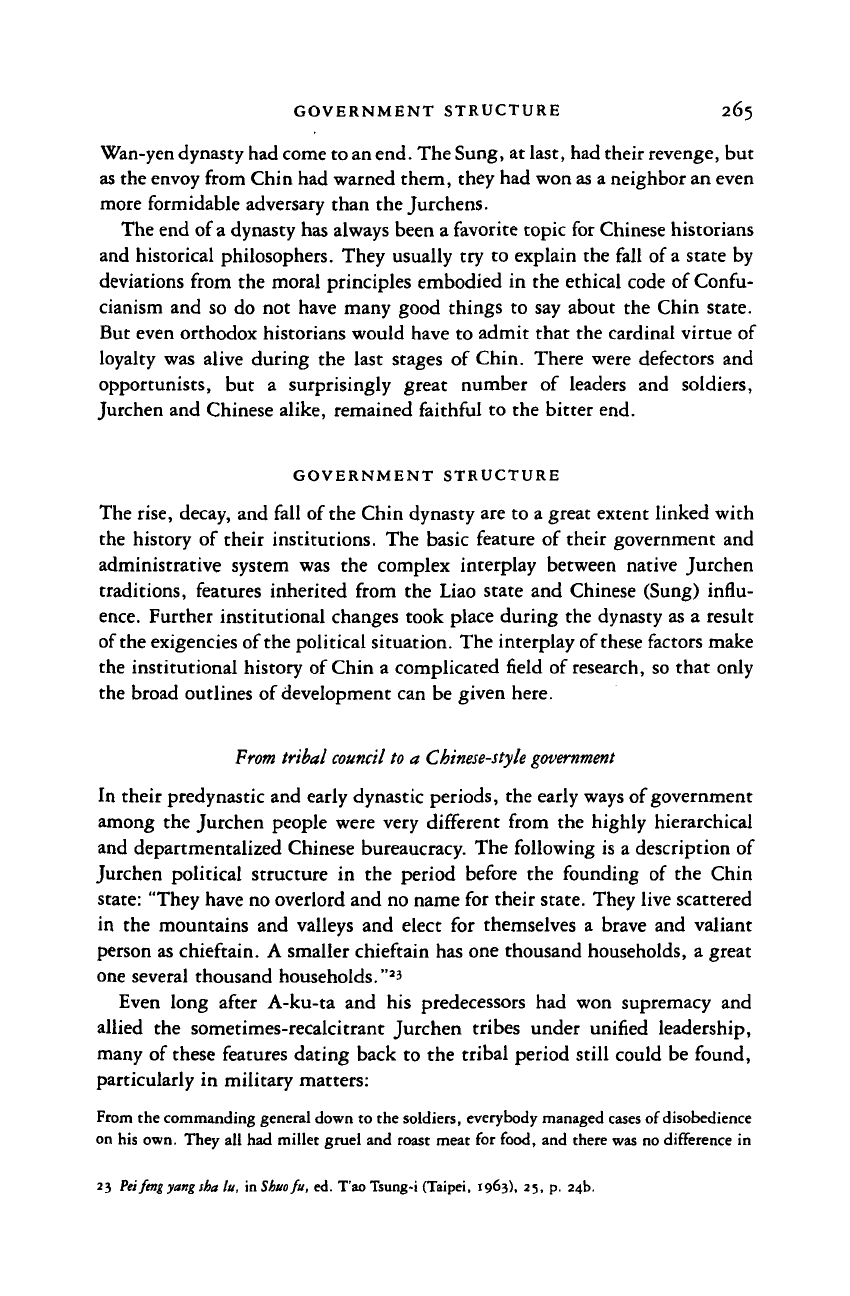

OGODEIS

AIN

ARMY

1230-31

TOLUI'S

ARMY

1230

Sung

Emperor

leaves

K'ai-feng

for Kuei-te

1223,ii.

Emperor

retreats to

Ts'ai-chou

1233,viii,

Siege 1233,xii.

City

falls

1234, ii.

MAP

22.

The destruction

of

Chin,

1234

certainly motivated

by

renewed Mongolian attacks against their own king-

dom.

The

Chin,

on

their part,

had

given

up all

hopes

for an

expansionist

policy

and

were content

to

stabilize their state within

its

existing borders.

They even achieved some local victories over

the Red

Coats

in

Shantung.

In 1227 Chinggis khan died while his campaign against Hsi Hsia

was

still in

progress. Ai-tsung tried

to

appease the Mongols by sending an embassy offer-

ing formal condolence, but the Mongols refused to receive the envoys

in

their

camp.

Already

in

1226, diplomatic relations between Hsi Hsia and Chin had

ceased; the last embassy from the Tangut court arrived in the Chin capital on 6

November 1226 and announced the death of the Tangut ruler. Chin dutifully

dispatched a mission of condolence four weeks later, but the Mongolian attack

against Hsi Hsia prevented its entry into Tangut territory. After the annihila-

tion of Hsi Hsia

in

1227 and the death of Chinggis khan on 25 August 1227,

the Chin enjoyed

a

brief period

of

respite from the Mongols.

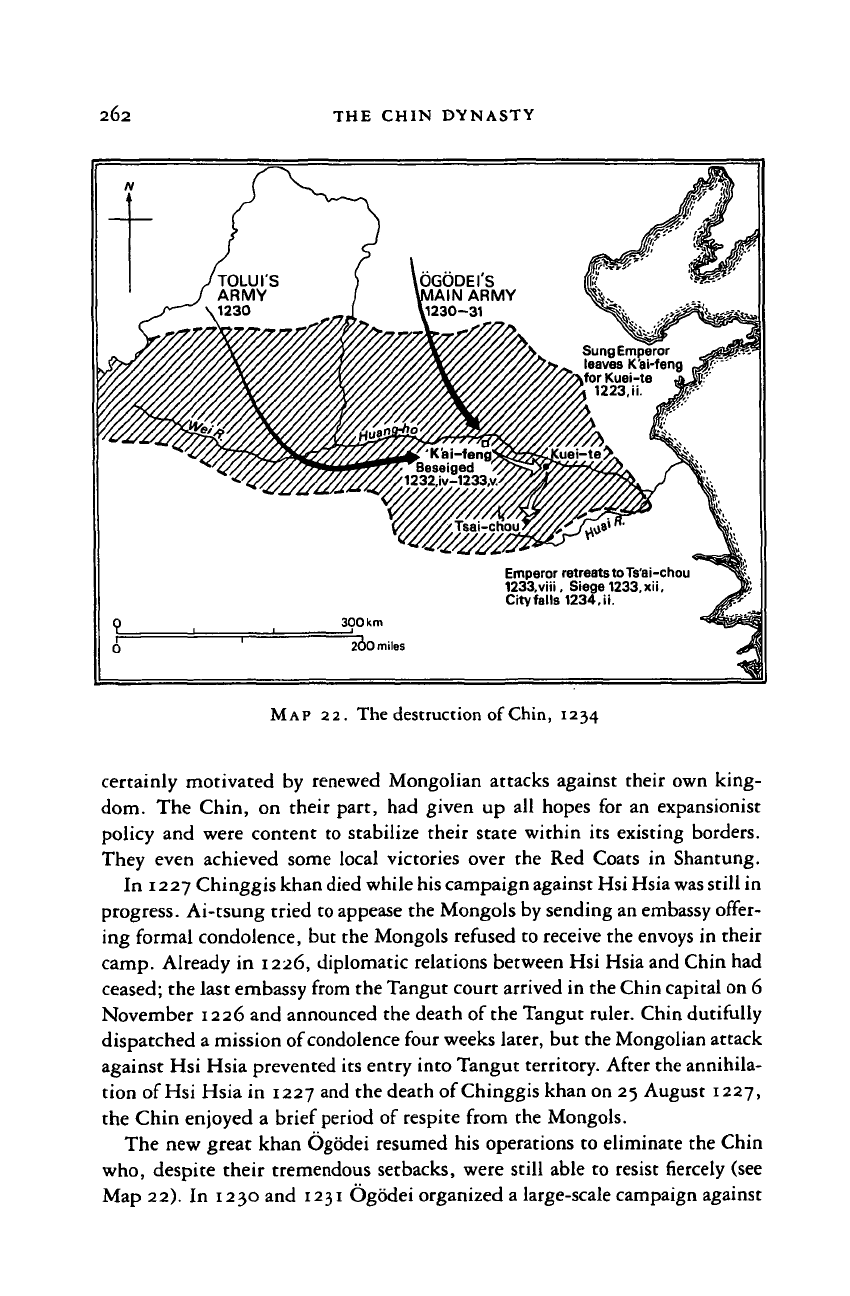

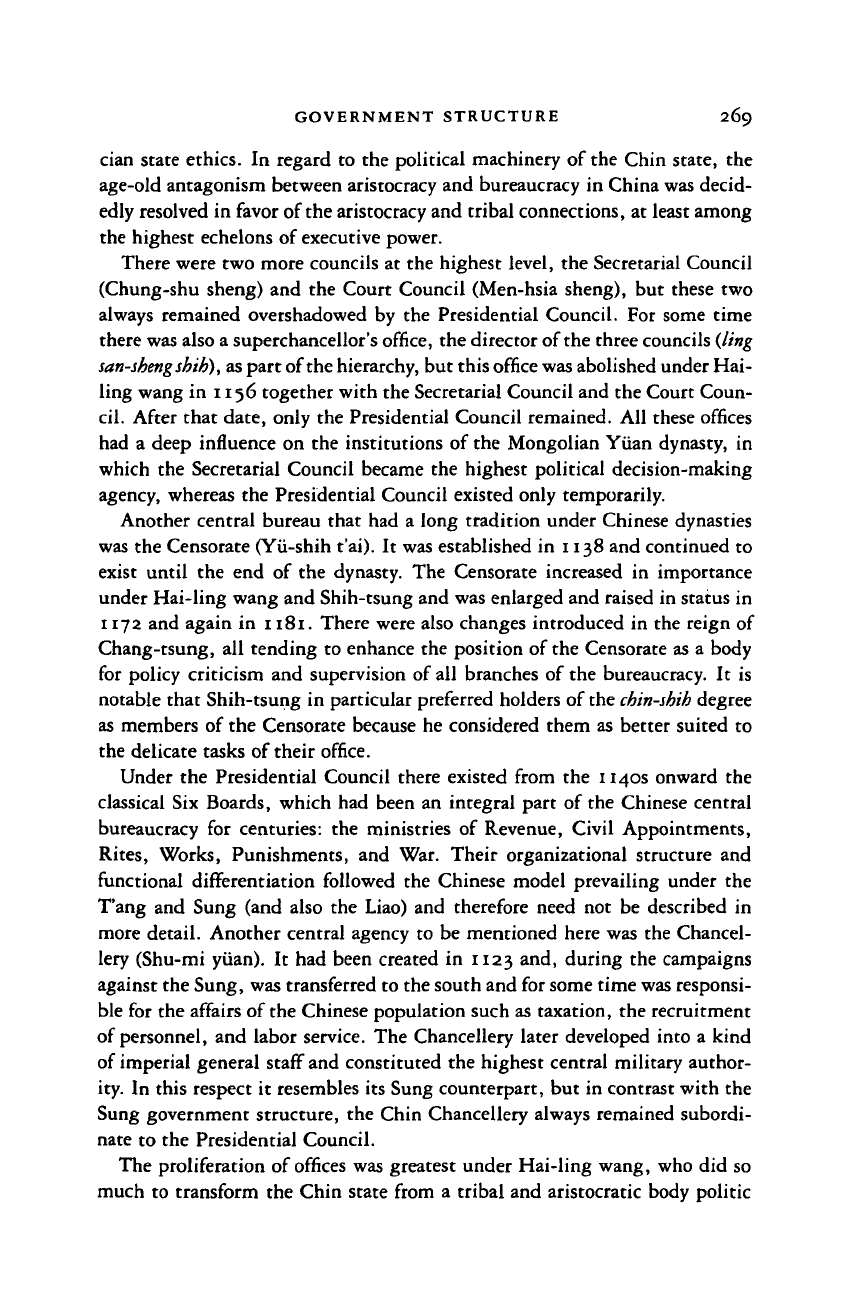

The new great khan Ogodei resumed his operations to eliminate the Chin

who,

despite their tremendous setbacks, were still able

to

resist

fiercely

(see

Map 22).

In

1230 and 1231 Ogodei organized a large-scale campaign against

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE ANNIHILATION OF CHIN 263

the Chin capital of Pien (K'ai-feng). Two columns were set in march, one

under Ogodei's command in Shansi and the other under Chinggis khan's

youngest son Tolui in Shensi. The strategic aim was a pincer attack on K'ai-

feng from the north and south. When both armies met in the winter of

1231-2,

they were put under the command of Siibetei, a distinguished

warrior whose forces ten years later would spread terror in Galicia and Hun-

gary. Although the Chin command had sent thirty thousand soldiers to

protect the northern flank of the capital at the Yellow River fords, on 28

January the Mongols were able to cross the river, and on 6 February the first

Mongolian cavalrymen appeared under the walls of the capital. The Chin

court tried feverishly to mobilize all able-bodied males in the capital and to

organize resistance against the attackers, who began their siege operations on

8 April 1232, about two weeks after they had asked for formal surrender and

hostages. Throughout these weeks the Chin government had tried desper-

ately to come to terms with the Mongols, and several further peace talks took

place during the summer of 1232. These came to a definitive end when on 24

July two Chin officers murdered the Mongolian envoy T'ang Ch'ing in his

hostel, together with some thirty other people. After this act of treachery the

Mongolian attacks were renewed with increased energy.

The situation in the besieged capital became chaotic and hopeless, particu-

larly after the outbreak of an epidemic in the summer of 1232. The provi-

sions stored for emergencies soon proved inadequate, and despite ruthless

requisitions of food among the population, the capital suffered from severe

famine. A graphic description of life in the capital during the siege has

survived; it is an eyewitness account by a Chinese intellectual who had held

offices under the Chin.

20

His moving account gives evidence of the total

disorganization within the government. Nominations, promotions, demo-

tions,

and executions of suspected traitors followed one another ceaselessly.

On the other hand, it is surprising that the city could be defended at all, for

it seems that the Jurchen and Chinese soldiers were able to put up an effective

defense against the Mongolian forces and their Chinese allies. The siege of

K'ai-feng is also of some interest for the history of military technology,

because gunpowder was used by both parties, if not as a propellant for

projectiles, then certainly for grenades hurled by catapults. These bombs

were used by the defenders of K'ai-feng against men and horses, with deadly

results. Another weapon credited to the inventiveness of Chinese artisans was

a flamethrower (or rocket?), called a "fire lance." Sixteen layers of strong

yellow paper were pasted together and formed into a pipe over sixty centime-

20 Liu Ch'i, comp., Kuei

ch'ien

chih, 11. This has been translated into German by Erich Haenisch in Zum

Untergattg zweier Rticht: Berichit von Augenztugtn am dm Jahrtn 1232—33 und 1368-70 (Wiesbaden,

•969).

PP- 7-26.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

264 THE CHIN DYNASTY

ters long. This pipe was filled with a mixture of charcoal made from willow

wood, iron filings, powdered porcelain, sulphur, and niter and was fastened

to a lance. The soldiers handling these weapons carried a small iron box with

glowing embers and, in battle, ignited the fire lances, which ejected a flame

over three meters long. When the explosives were spent, the pipes could be

reloaded."

In the winter the emperor decided to leave the city while it was still

possible. Followed by a host of

loyal

Jurchen and Chinese officials, he left for

Kuei-te in Honan where he arrived on 26 February 1233, and later in that

summer, on 3 August 1233, he found refuge in Ts'ai-chou. The capital was

thus left in the hands of the commanding generals. One of

these

was Ts'ui Li.

He planned to avert the worst for the capital and for himself

by

preparing to

surrender, because if K'ai-feng had been taken by storm, indiscriminate

slaughter and pillage would have resulted. The officials and generals who

were still loyal to the absent emperor were eliminated, and on 29 May the

city gates were opened to the soldiers of

Subetei.

The capital was plundered

in a "normal" way, but it seems that soon barter trade between the inhabit-

ants and the northerners was permitted; the townspeople gave their last

possessions, valuables, and silk in exchange for rice and grain transported

from the north. Some slaughter occurred nevertheless. Over five hundred

male members of the Wan-yen clan were marched out of the city and massa-

cred. Ts'ui Li, who might have cherished hopes for a high position in the

Sino-Mongolian hierarchy, did not enjoy the fruits of his coup, as he was

assassinated by a Chin officer whose wife he had allegedly insulted.

The fall of K'ai-feng still left the Mongols to administer the final coup de

grace to the remnants of

the

Chin imperial court. Ai-tsung's situation was so

desperate that envoys were sent to the Sung to ask them for grain and to point

out that the Mongols were a great danger and that they would destroy the Sung

in their turn. The Sung commanders of course refused any assistance and

continued to prepare a joint attack with the Mongols against the last Chin

strongholds. But even so, the prefectural town of Ts'ai-chou held out for some

time after the attacks began in December 1233. After an unsuccessful attempt

to flee from the town, Ai-tsung ceded his "throne" to a distant relative and

committed suicide. This man, too, fell in the street fighting when Mongolian

soldiers

finally

entered the town on 9 February 1234." The Chin state and the

21 CS, 116, p. 2548. For the bombs or grenades, see CS, 113, p. 2495-6. For a more recent study, see

Jixing Pan, "On the origin of rockets," Toungpao, 73 (1987), pp. 2-15.

22 The account of the events in Ts'ai-chou in the Chin sbib is largely based on the Ju-nan i sbib, a text

written by an eyewitness, Wang E. On the author, who lived from 1190 to 1273, see Hok-lam Chan,

"Prolegomena to the Ju-nan i sbib: A memoir of the last Chin court under the Mongol siege of 1234,"

Sung Studies

Newsletter,

10, suppl. 1 (1974), pp. 2-19; and Hok-lam Chan, "Wang 0(1190-1273),"

Papers

an Far

Eastern

History, 12 (1975), pp. 43-70.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE 265

Wan-yen dynasty had come to an

end.

The Sung, at last, had their

revenge,

but

as

the envoy from Chin had warned them, they had won

as

a neighbor an even

more formidable adversary than the Jurchens.

The end of a dynasty has always been a favorite topic for Chinese historians

and historical philosophers. They usually

try to

explain the fall of

a

state

by

deviations from the moral principles embodied

in

the ethical code of Confu-

cianism

and so do not

have many good things

to say

about

the

Chin state.

But even orthodox historians would have

to

admit that the cardinal virtue of

loyalty

was

alive during

the

last stages

of

Chin. There were defectors

and

opportunists,

but a

surprisingly great number

of

leaders

and

soldiers,

Jurchen and Chinese alike, remained faithful

to

the bitter end.

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE

The rise, decay, and fall of the Chin dynasty are

to

a great extent linked with

the history

of

their institutions.

The

basic feature

of

their government

and

administrative system

was the

complex interplay between native Jurchen

traditions, features inherited from

the

Liao state

and

Chinese (Sung) influ-

ence.

Further institutional changes took place during the dynasty as

a

result

of the exigencies of the political situation. The interplay of these factors make

the institutional history of Chin

a

complicated field

of

research, so that only

the broad outlines of development can be given here.

From tribal council to a Chinese-style government

In their predynastic and early dynastic periods, the early ways of government

among the Jurchen people were very different from

the

highly hierarchical

and departmentalized Chinese bureaucracy. The following

is

a description of

Jurchen political structure

in the

period before

the

founding

of the

Chin

state:

"They have no overlord and no name

for

their state. They live scattered

in

the

mountains

and

valleys

and

elect

for

themselves

a

brave

and

valiant

person as chieftain. A smaller chieftain has one thousand households, a great

one several thousand households."

23

Even long after A-ku-ta

and his

predecessors

had won

supremacy

and

allied

the

sometimes-recalcitrant Jurchen tribes under unified leadership,

many

of

these features dating back

to the

tribal period still could

be

found,

particularly

in

military matters:

From the commanding general down

to

the soldiers, everybody managed cases of disobedience

on

his

own. They

all

had millet gruel

and

roast meat

for

food,

and

there was

no

difference

in

23 Peifengyangshalu, in

Shuofu,

ed.

T'aoTsung-i (Taipei, 1963),

25, p. 24b.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

266 THE CHIN DYNASTY

quality between high and low. When their country is involved in great affairs [war], they all

go out into the wilderness and sit down in a circle, drawing in the ashes. Then they deliberate,

starting from the lowest one present. When the council has come to an end, they wash away

[the charcoal], and not a human voice is heard - such is their secrecy. When the army is about

to march, a great reunion with a banquet is held, at which strategic proposals are offered. The

generalissimo listens and then selects among these what is appropriate; then immediately a

special leader is appointed for its execution. When the army returns after a victory, another

great reunion takes place, and it is asked who has won merits. According to the degree of

merit, gold is handed out; it is raised and shown to the multitude. If they think the reward too

small, it will be increased.

24

It was a long time before the vestiges of these semiegalitarian customs

disappeared. A-ku-ta, for example, did not expect his officials to kowtow

before him. The gulf that existed in Chinese hierarchical thinking between

an emperor and his subjects was unknown under the early Chin rulers, and

the growing autocracy under Hsi-tsung and Hai-ling wang was, in a certain

respect, nothing but an adoption of Chinese ways. Even as late as 1197,

when the state structure has been patterned after the Chinese model, we find

a curious case of imitation of

the

old tribal council customs. The question was

whether or not the Mongols should be attacked. A vote was taken among the

highest officials, and the court historians have duly recorded the outcome of

this poll: Out of eighty-four, only five favored an attack; forty-six were for a

defensive strategy, and the rest preferred alternating between attack and

defense.

2

'

On the other hand, some sort of central control became imperative as soon

as the range of government actions was enlarged, through diplomatic con-

tacts but chiefly through the acquisition of new territories. A-ku-ta therefore

created a system of what may be called prime ministers. These were called

po-

chi-lieh

in Chinese; the Jurchen word was something like

bogile.

It survived in

the Manchurian language as

beile

and was used by the Manchus until the

beginning of the twentieth century as the designation for a high dignitary.

The original meaning of

bogile

seems to have been "leader,

chief,"

and it was

already in use in the predynastic period, because A-ku-ta was elected su-

preme

bogile

in 1113 when he succeeded his brother.

The assumption of this title supplanted the honorary designation as mili-

tary governor, which had customarily been conferred on him by the Liao

rulers,

and illustrates the high prestige attached to the rank of

bogile.

Another

proof of this prestige is the fact that only close relatives of the emperor from

the Wan-yen clan bore this title. Usually the various

bogile

titles established

in 1115 were prefixed by the word

gurun

(Chinese:

kuo-lun),

"state, nation."

24 Pa fmg yang sha lu, 25, p. 25b. Sec also Ta Chin kuo cbib, 36, pp. 278-9, for a brief summary of the

military practices of the early Jurchens.

25 CS, 10, p. 242.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE 267

The highest office was that of the "great leader," held by the presumptive

heir to the throne. Other

bogile

were called "commanding leader," "first

leader," "second leader," "third leader," and "assistant leader"; these mean-

ings have been transmitted through both the Jurchen words (transcribed with

Chinese characters) and Chinese glosses.

The rank of assistant leader was not as high as the others and was mostly

conferred on generals during campaigns. The description of the various

bogile

offices in the contemporary sources indicates that there was already some

degree of functional differentiation. The commanding leader was the head of

political affairs in general, with the second and third leaders as his deputies.

There was also a

bogile

whose chief duties were in the diplomatic field,

namely, the

i-shih

bogile

(the first part of this word is still unexplained).

Although this differentiation may be regarded as the beginning of

a

special-

ized bureaucracy (all the

bogile

had their own subordinate staff), it would be

erroneous to regard these titles as offices in the strict sense. They were far

more a distinction conferred ad

personam,

because some

bogile

offices were

abolished when their incumbents died. Many changes were made in the

bogile

system, which in its later stages showed Chinese influence even in its nomen-

clature, until it was abolished altogether shortly before T'ai-tsung died

("34-5)-

By that time, the Jurchens had expanded their domination not only over

the former territory of the Liao state but also over great parts of northern

China, chiefly Hopei and Honan. They were thus faced with the problem of

how to rule a state comprising many different ethnic groups with different

economic and social backgrounds. In terms of numbers the Chinese certainly

were a majority, including both the Chinese inhabitants of the former Liao

state and those in the newly conquered regions. At first

the

Jurchens followed

the example set by the Khitans under the Liao dynasty, in which a marked

dualism had existed: The Khitans and their related tribes continued to be

administered by their own tribal organization, whereas the Chinese were

subjected to an administration modeled on Chinese patterns, largely inher-

ited from the T'ang dynasty.

A similar dualism was practiced after the conquest of the Central Plains.

The Jurchen people were organized into units of their

own

(the

meng-an

mou-k'o;

see the next section). For the administration of the newly conquered regions

in China proper, a new authority was created in 1137, named the Mobile

Presidential Council (Hsing-t'ai shang-shu

sheng).

This organization existed

from n

37

to 1150 and was revived as a measure of military expediency after

1200.

The Mongolian Yuan dynasty later took it over from Chin and trans-

formed it into a full system of provincial administration. The term

sheng

for

province, which now forms part of the administrative system of the Chinese

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

268 THE CHIN DYNASTY

People's Republic, thus goes back to a Chin institution that had lasted

through the Yuan, Ming, and Ch'ing dynasties into the Republican period

after 1911. The Chin name Mobile Presidential Council indicated that it was

originally mobile, that is, not located a priori in a definite town, as all

Chinese administrative units usually were, but assigned to whatever place

seemed politically preferable. At the same time, the organization was not

conceived as an independent unit. It was a branch office of the Presidential

Council (Shang-shu sheng) and thus subordinated to a metropolitan agency.

The transition from the rule of Jurchen generals over the newly conquered

regions and their population to a more centralized type of administration was

carried a great step forward with the creation of this instrument of centralized

control. One of the many duties of the organization was the recruitment of

bureaucratic personnel through civil service examinations. The dissolution of

the state of Great Ch'i in 1136—7 opened the way for former civil servants of

Ch'i to enter the new bureaucracy of Chin. The leading positions remained,

however, a prerogative of Jurchen dignitaries.

The same is true for the Presidential Council

itself.

It had been established

as early as 1126 in the Supreme Capital in Manchuria at a time when the

campaign against Sung was still in full swing. It soon grew into a full-

fledged prime minister's office and remained the chief policymaking agency

under the Chin. The name of the council itself

as

well as those of its various

subordinate offices were Chinese. The leading personnel were mostly mem-

bers of the imperial clan and other Jurchen dignitaries. In later years some

Khitans, Hsi, and a few Chinese and Po-hai also rose to these most powerful

ranks in the bureaucracy.

The highest office in the Presidential Council was that of left prime

minister

(tso

ch'eng-hsiang).

Out of the sixteen persons who held that office

over the years, no fewer than eleven came from the imperial Wan-yen clan;

four were from other Jurchen clans; and one was a Po-hai. The office of right

prime minister was held consecutively by five imperial clansmen, two other

Jurchens, two Po-hai, three Khitans, and two Chinese. The lower echelons of

the Presidential Council showed a larger proportion of Khitans and Chi-

nese.

26

The preponderance of imperial clansmen is interesting because it

contrasts with the usage under Chinese dynasties, in which under both T'ang

and Sung, members of the imperial clan were rarely if ever promoted to

senior ministerial posts.

Clan affiliation was, therefore, for the Jurchen state of Chin, a far more

powerful guarantee of loyalty than was the abstract behavioral code of Confu-

26 Mikami Tsugio, Kindai uiji

seido no

kenkyu, Kinshi kenkyu no. 2 (Tokyo, 1970), p. 217, provides a

table of the highest offices broken down on the basis of the nationality of the incumbents.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE 269

cian state ethics. In regard to the political machinery of the Chin state, the

age-old antagonism between aristocracy and bureaucracy in China was decid-

edly resolved in favor of the aristocracy and tribal connections, at least among

the highest echelons of executive power.

There were two more councils at the highest level, the Secretarial Council

(Chung-shu sheng) and the Court Council (Men-hsia sheng), but these two

always remained overshadowed by the Presidential Council. For some time

there was also a superchancellor's office, the director of the three councils {ling

san-shengshih), as part of the hierarchy, but this office was abolished under Hai-

ling wang in 1156 together with the Secretarial Council and the Court Coun-

cil.

After that date, only the Presidential Council remained. All these offices

had a deep influence on the institutions of the Mongolian Yuan dynasty, in

which the Secretarial Council became the highest political decision-making

agency, whereas the Presidential Council existed only temporarily.

Another central bureau that had a long tradition under Chinese dynasties

was the Censorate (Yii-shih t'ai). It was established in 1138 and continued to

exist until the end of the dynasty. The Censorate increased in importance

under Hai-ling wang and Shih-tsung and was enlarged and raised in status in

1172 and again in 1181. There were also changes introduced in the reign of

Chang-tsung, all tending to enhance the position of the Censorate as a body

for policy criticism and supervision of all branches of the bureaucracy. It is

notable that Shih-tsung in particular preferred holders of the

chin-shih

degree

as members of the Censorate because he considered them as better suited to

the delicate tasks of their office.

Under the Presidential Council there existed from the 1140s onward the

classical Six Boards, which had been an integral part of the Chinese central

bureaucracy for centuries: the ministries of Revenue, Civil Appointments,

Rites,

Works, Punishments, and War. Their organizational structure and

functional differentiation followed the Chinese model prevailing under the

T'ang and Sung (and also the Liao) and therefore need not be described in

more detail. Another central agency to be mentioned here was the Chancel-

lery (Shu-mi yuan). It had been created in 1123 and, during the campaigns

against the Sung, was transferred to the south and for some time was responsi-

ble for the affairs of the Chinese population such as taxation, the recruitment

of personnel, and labor service. The Chancellery later developed into a kind

of imperial general staff and constituted the highest central military author-

ity. In this respect it resembles its Sung counterpart, but in contrast with the

Sung government structure, the Chin Chancellery always remained subordi-

nate to the Presidential Council.

The proliferation of offices was greatest under Hai-ling wang, who did so

much to transform the Chin state from a tribal and aristocratic body politic

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

270 THE CHIN DYNASTY

into a Chinese bureaucracy. Toward the end of the twelfth century there was

hardly a central government office that did not have its counterpart in the

Sung state. The names were perhaps different, but the functions were the

same. This is also true for such eminently traditional Chinese offices as those

for astronomy and astrology, national historiography, and the many bureaus

and departments dealing with the administration of the imperial household

and ceremonial affairs.

In one respect, however, the Chin dynasty was a faithful follower of Liao-

Khitan (and Po-hai) precedents. Unlike a proper Chinese dynasty, which

normally had one capital, the Liao had five capitals, as did the Chin. In both

cases this can be interpreted as a remnant of the times when even the rulers

had no fixed abode, but it was also a remnant of a ritualized system of

seasonal sojourns. On a more practical level, the system of multiple capitals

also provided the means to establish centralized agencies in more than one

locality. The five-capital system of the Chin is particularly complicated be-

cause names like Southern or Central capital were given to different towns in

different periods (see Table 4).

The shift of the main centers of power is clearly reflected in the transfer of

names. Yen-ching (Peking) was the Southern Capital until Hai-ling wang

made it the center of the state. Thereafter it became the Central Capital.

After Peking had been abandoned to the Mongols, Lo-yang became the

Central Capital.

Local government in the predominantly Chinese parts of the state closely

followed the Chinese models as developed under the Sung and T'ang dynas-

ties,

and it is therefore without characteristics peculiar to the Chin govern-

ment system. Counties

(hsien)

and prefectures (fu or

chou)

were the basis of

local administration, and they were administered more or less as they were in

contemporary Sung China. The next-higher administrations, corresponding

to provinces, were the routes (/«), of which there were nineteen. The only

difference between Sung and Chin administration on the local and provincial

level was in the partly military, partly tribal organization of the border areas.

These will be described briefly in the section on the military organization of

the Chin.

Selection of personnel

Even the short outline of Chin government structure in the preceding chapter

showed that the bureaucratic framework of

the

state called for a great number

of officials. For the later periods of Chin we have

figures

that give some idea of

the bureaucracy's numerical strength. In 1193 there were 11,499 officials, of

whom 4,705 were Jurchens and 6,794

w

^re

Chinese.

This

figure

is said to have

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008