The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

100

2O0

30Okm

100 200miles

Chinarmydefeatedby

HanShih-chung H30,iv.

iTing-hai

'ang-kuo

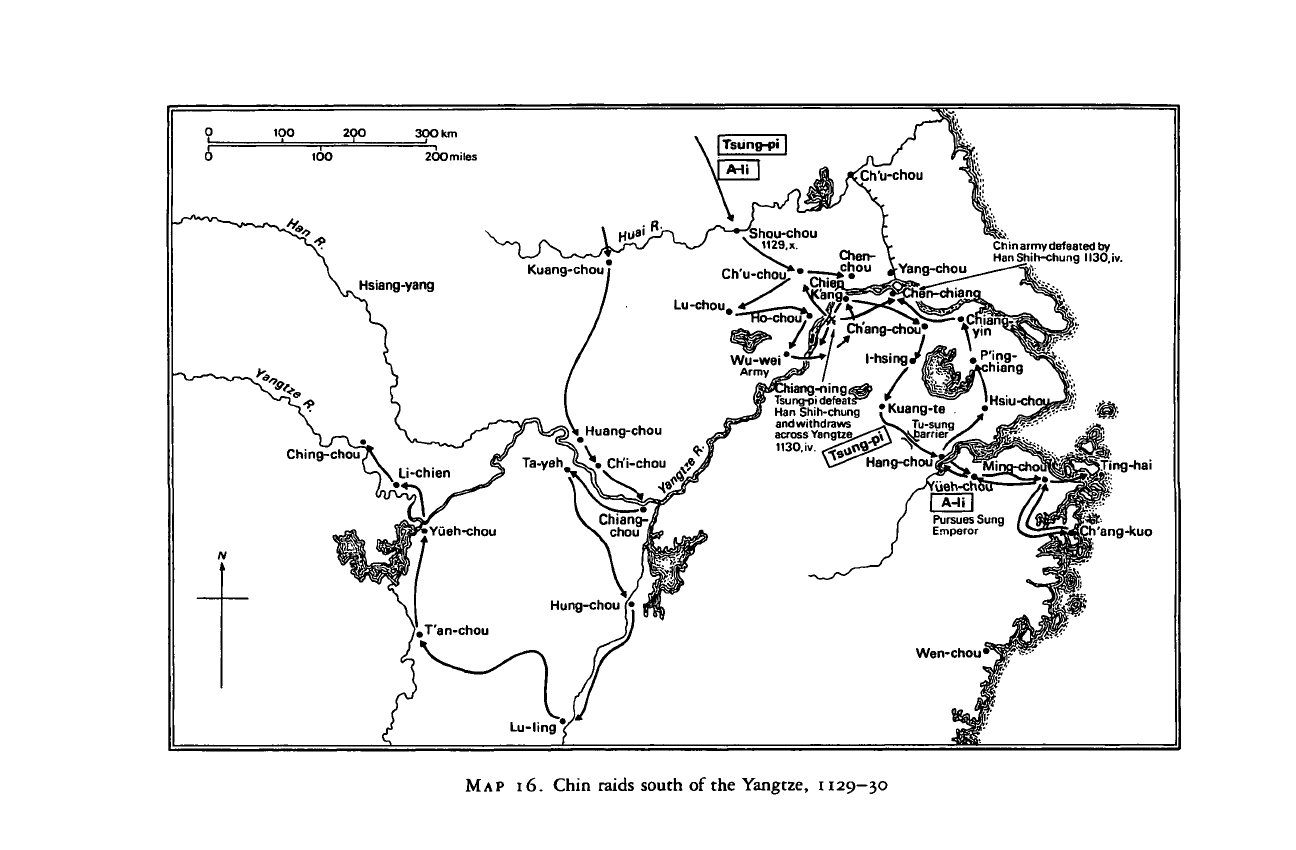

MAP

I

6. Chin raids south

of

the Yangtze, 1129—30

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

232 THE CHIN DYNASTY

capital at K'ai-feng in 1132. He tried hard to organize north China by

establishing a workable administration and reviving the stagnant economic

life of his territory. Compulsory military service and heavy taxation were

imposed on the population. His troops fought alongside

the

Jurchens against

the Sung and even scored a few victories, such as the capture of the strategic

town of Hsiang-yang in 1135.

But the Sung counteroffensive under Yiieh Fei in 1134—5 ended in the

reconquest of much of the lost territory. This turn of events did much to

discredit Liu Yii's military value to the Jurchens. In 1135 his protector, the

Chin emperor T'ai-tsung, died and his successor, a grandson of A-ku-ta, later

canonized as His-tsung (1119—49), proved much less favorably inclined

toward Liu Yii. Late in 1137 the state of Ch'i was abolished and Liu Yii was

demoted from the rank of emperor

(huang-ti)

to that of prince

(wang).

It

seems that he was even suspected of having opened secret negotiations with

Yiieh Fei. Liu Yii was transferred first to Hopei and then to the town of Lin-

huang in northwestern Manchuria where he was allowed to end his life in

supervised retirement. The experiment of organizing the Jurchen conquests

as a Chinese puppet state with the help of Chinese defectors had thus failed,

and the Chin were faced with the alternative of either trying to achieve

coexistence with the Sung or continuing their policy of aggression and annihi-

lation of the Sung.

It is hard to say when the Chin finally realized that the Sung empire could

not be conquered. There had been abortive peace talks as early as 1132. One

factor that perhaps influenced the Jurchen decision to come to terms with the

Sung was the death of the former Sung emperor Hui-tsung in n

35,

in Wu-

kuo-ch'eng, a town in the Sungari region of Manchuria where he had been

held as a captive together with the other members of

his

former court.

The Chin government had appreciated that the imperial prisoners in their

custody were a diplomatic asset of the first order, and therefore their treat-

ment had been relatively lenient. The gradual improvement of their fate can

be shown from Chin sources (Sung sources remain silent on this point). In the

beginning, in 1127, Hui-tsung and Ch'in-tsung had been degraded to the

status of commoners and in 1128 were forced to pay obeisance to the ances-

tral spirit of A-ku-ta in the latter's mausoleum, wearing mourning dress

—

a

ritual of expiation imposed on supposed war criminals. Then the former

emperors were formally enfeoffed as marquises

(bou)

with the insulting titles

of Hun-te (Muddled Virtue) and Ch'ung-hun (Doubly Muddled). Six Sung

princesses were given as wives to members of the imperial Wan-yen clan of

Chin. In 1137, the Sung court was formally notified of Hui-tsung's death,

and when a peace treaty was in sight (1141), Hui-tsung received the posthu-

mous rank of prince of T'ien-shui chiin; his surviving son Ch'in-tsung, that

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHIN-SUNG RELATIONS BEFORE II42 233

of duke (kung) of T'ien-shui chiin

—

even the Chin respected the status differ-

ence of generations.

Note also that the name of their new fief was a perfectly neutral one and

not derogatory, as their former titles had been. T'ien-shui was a commandery

at the upper course of the Wei River in the eastern part of what is now Kansu

Province. A few months later Ch'in-tsung was given the emoluments due his

ducal rank. After the treaty had been concluded, the male relatives of the two

emperors who were still in Chin captivity were accorded emoluments, a

privilege that was extended in 1150 to the female descendants of the former

Sung emperors. In other words, the Chin treated their captives as hostages

who could always be used to bring pressure on the Sung. The death of Ch'in-

tsung in 1156, however, deprived the Chin of their principal hostage on

whom they could rely to prevent the Sung from breaking the peace treaty.

This treaty of 1142, which was to regulate Sung-Chin relations for almost

twenty years, was the result of protracted negotiations. The Chin had the

advantage of being able to use the return to the Sung of the coffins of Hui-

tsung, his empress, and the emperor's mother as a bargaining chip. In

addition they kept up the military pressure by repeatedly sending troops into

the territory south of the Yellow River and in 1140 again conquered the

whole of Honan and Shensi, which had been returned to Sung control early in

1139 after the conclusion of a preliminary peace. But the conclusion of a

peace treaty would not have been possible if the revanchists had remained in

power at Hangchou, where the Sung had finally established their capital in

1138.

The elimination of Yiieh Fei, the most successful and popular of the

Sung generals, by his adversary Ch'in Kuei opened the way toward a final

agreement. In 1141 Yiieh Fei was ignominiously put to death in his prison, a

foul deed that made the advocate of coexistence, Ch'in Kuei, forever a bete

noire in Chinese history.

Almost at the same time, negotiations between Sung and Chin were

initiated. These were extremely involved and protracted. It seems that the

Chin side, through the commander Wan-yen Tsung-pi, signaled to the Sung

that a peace could be obtained by agreeing to make the Huai River the border

between the two states. This was in October 1141. Wan-yen Tsung-pi was

the fourth son of A-ku-ta and had been entrusted with operations in central

China. Two months later the Sung agreed in principle. Extracts from state

letters of both sides have survived in Sung sources; their dates range from

October 1141 to October 1142. But the texts of the treaty

itself,

or, more

correctly, the oath-letters of Chin and Sung, have not survived. What we

have is an abbreviated version of the Sung oath submitted already by the end

of 1141. The terms of peace were harsh. The Sung agreed to have the middle

course of the Huai River as a border, which meant that the whole of the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

234 THE CHIN DYNASTY

Central Plains was lost to the invaders. Also, the two strategically located

prefectures of Tang and Teng (in modern Hupei), which were to play a

significant role in the war of 1206, were ceded to Chin. From 1142 onward,

annual tributes of silver and silk amounting to 250,000 ounces and bolts,

respectively, were to be paid each year in the last month of spring; the

payment was to be delivered to the Chin border town of Ssu-chou on the

northern bank of the Huai River. Additional terms concerned security along

the border. Fugitives from Sung to the north could not be pursued, and no

large garrisons could be stationed in the Sung border prefectures. At the

same time Sung promised not to hide fugitives from the north but to surren-

der them.

The wording of the Sung declaration is characterized by extreme humility,

which acknowledged the Sung's new vassal status. Chin is addressed as "Your

superior state," whereas Sung termed itself "our insignificant state." Equally

humiliating was the use of the word "tribute"

(kung)

for the annual pay-

ments. But the worst loss of face was that Sung was no longer regarded by

Chin as a state in its own right, but rather, as a vassal, and it is understand-

able that no Sung source has preserved the text of the Chin decree that

invested Kao-tsung, whose personal name was Chao Kou, as ruler of the

Sung state. It has been preserved, however, in the biography of Wan-yen

Tsung-pi, along with the covering letter accompanying Kao-tsung's oath-

letter.

8

The Sung emperor must have regarded the extorted documents as the

nadir of his career. To call himself "Your servant Kou" must have taxed to the

extreme his gift for self-denial.

The Chin diplomat who presented the investiture document to Kao-tsung

was a Chinese who had formerly been in the service of the Liao and found

employment at the Chin court. He was received by Kao-tsung in a formal

audience on 11 October 1142, a date that must be regarded as the actual end

of hostilities and the beginning of a new period of coexistence. The Chin

withdrew their armies and promised to return to the Sung the coffins of Hui-

tsung and the empresses. It is surprising that the surviving documents of the

negotiations and the short version of Kao-tsung's oath-letter do not mention

the resumption of trade between the two countries, but this is certainly due

to the deficiency of the sources. In fact, licensed border markets were estab-

lished, the most important one being Ssu-chou. Trade soon began to flourish

again.

For the Chin the stabilization of their southern border and the final

8 CS, 77, pp. 1755—6. For a general study of treaties between Sung and Chin, see also Herbert Franke,

"Treaties between Sung and Chin," in

Etudes

Song in

memoriam Elienne

Balazs, ed. Franjoise Aubin, 1st

series,

no. i (Paris, 1970), pp. 55-84.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE POLITICAL HISTORY

OF

CHIN AFTER II42

235

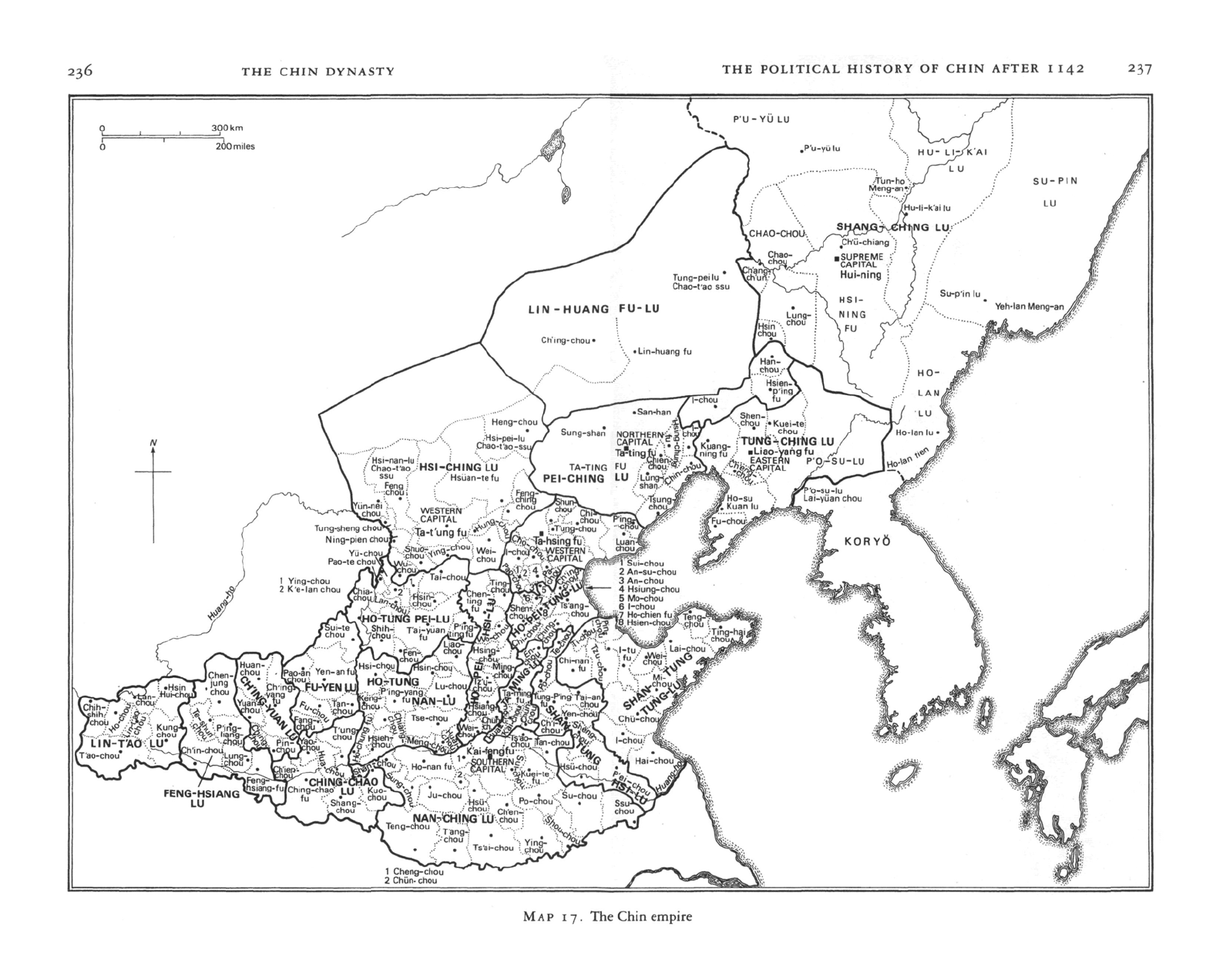

conquest of

the

Central Plains brought about a gradual shift of their political

and economic centers from north to south (see Map 17). More and more

Jurchens settled in north China; the Chin had at last become a state that was,

ethically and economically, to a great extent Chinese. For the Sung, too, the

consolidation brought about by the treaty proved a considerable asset. De-

spite the formal vassal status that he had had to accept, Kao-tsung had

stabilized the situation and had, moreover, fulfilled the moral duties of filial

piety by recovering the body of Hui-tsung and securing the release of his

mother. The Chin refused, however, to free Ch'in-tsung, a refusal that was

probably not entirely unwelcome to Kao-tsung, whose position as emperor

would have become precarious had his older brother returned.

THE POLITICAL HISTORY

OF

CHIN AFTER II42

A period of peaceful coexistence thus seemed to lie ahead after 1142. It was

interrupted twice during the following seventy years, once by the Chin and

once by the Sung, thus demonstrating that revanchism had not died out with

the 1142 treaty and remained a constant matter of controversy in court

circles. The years immediately following the treaty were, however, peaceful

for both states. The Chin state had asserted itself

as

a power in China proper

and continued to transform itself into a Chinese-style political entity. This

transformation from a more tribal, feudal society into a bureaucratic organiza-

tion did not take place without some resistance from the more conservative

faction among the Jurchen grandees. The ruler Hsi-tsung (r. 1135-50)

himself had been enthroned when he was a boy and had never taken a

prominent part in the diplomatic and military activities that occurred after

his accession. He left all this to the imperial clan members who held the

highest military and civilian offices. The strong personal leadership shown by

T'ai-tsu and T'ai-tsung was absent in their successor, who

was,

moreover, not

a very capable person and even more addicted to drinking than was usual

among the hard-drinking Jurchens. As long as the Chin state was not con-

fronted with any critical situation, a ruler like Hsi-tsung might be tolerated

by the more farsighted members of the imperial clan, and indeed there was

not much to interfere with his pursuit of personal pleasure. It is true that

some border warfare broke out with the unruly inhabitants of the northwest-

ern steppe regions, but following the Sung example the Chin now adopted a

policy of appeasement.

In this context the Mongols played a prominent role. It seems that already

in the mid-twelfth century their tribe had been consolidated enough to be

regarded by the Chin government as the potential partner of an agreement.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2

3

6

THE

CHIN DYNASTY

THE POLITICAL HISTORY

OF

CHIN AFTER II42

237

300 km

260mil

...

':

Heng-chou

/Hsi-pei-lu

Chao-t'ao-ss

CAPITAL

."; "11

f

K

* : I

UNli

-r

UKIMU

LU /

TAingfti.•:.?•...?ningfi / •Liao-yahgfu J

-..

QPien'il./ .\

M

>.,... EASTERN PO/-SU-

Hsim-chou^-..jfhou

=

.

W

:

.

/Ting-hai^'

.:

chou

/

xv*>: liarig-

LiN-TAoau*

L.•••;"••&*•'

T

,

. .

••—^JCh'in-chou,

Tao-chou

;. ^^T^ /

-Lung

Lchou

FENG-HSIANG

LU

:;

T'ang-.

#

' '

.

.;' . •:

Ts'ai-chou

1 Cheng-chou

2

Chiin.

chou

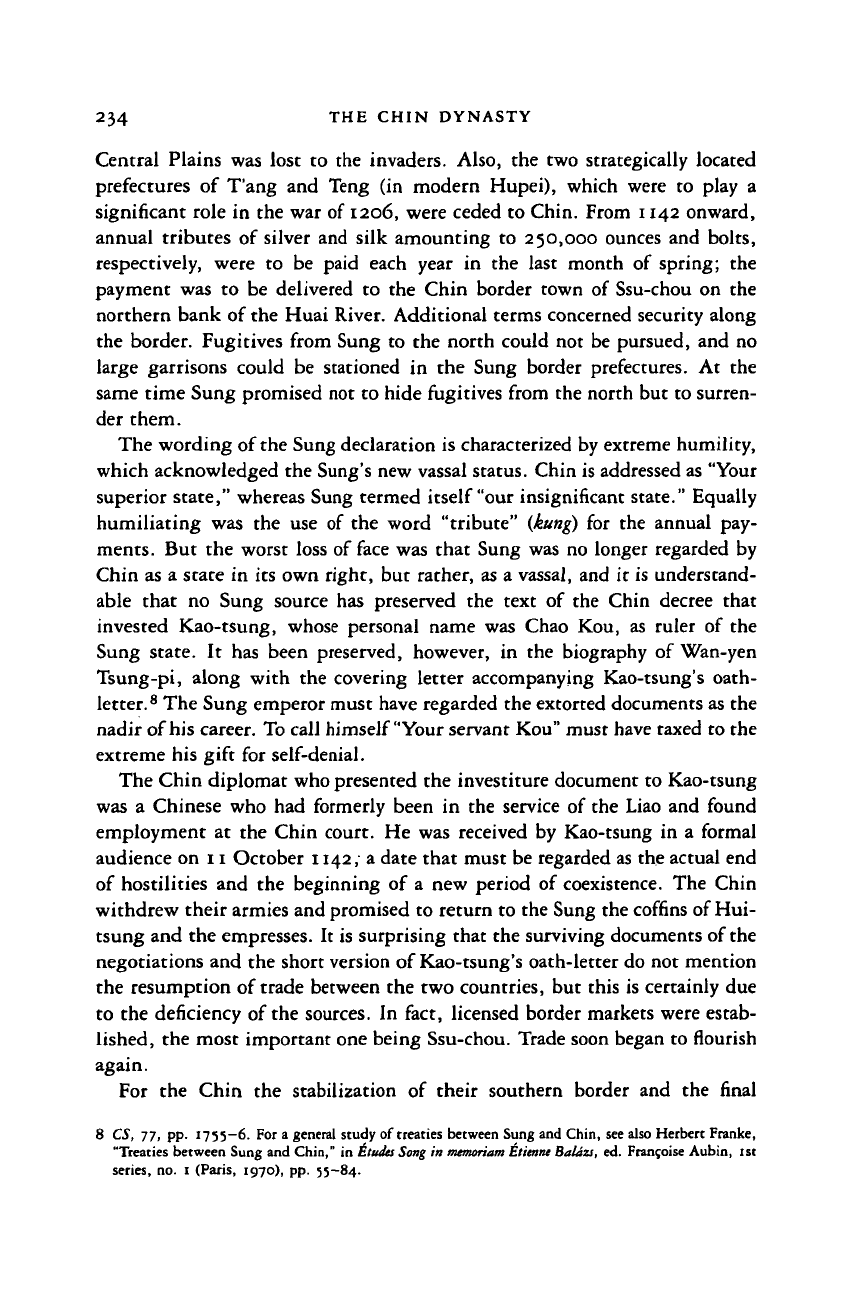

MAP

17.

The Chin empire

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

238 THE CHIN DYNASTY

Chinese sources of Sung provenance record that in 1146-7 the state of the

Mongols was "pacified" and that

its chieftain Ao-lo Po-chi-lieh was invested as assisting state ruler of the Meng. Then peaceful

relations were established, and Chin annually gave them very generous presents. Thereupon

Ao-lo Po-chi-lieh called himself Ancestral Originating Emperor [Tsu-yiian huang-ti] and

proclaimed the era t'ien-hsing [Heavenly

Rise].

The great Chin had used military force but

eventually could not subdue them [the Mongols] and only sent elite troops that occupied some

strategic points and then returned.

9

It is not clear to which Mongolian chieftain the term Ao-lo Po-chi-lieh refers.

It is a composite title; the second half is the Jurchen word

bogile,

"leader,

chief."

The first half of the title could be a transcription of the Mongolian

word a'uruigh), "base, camp," so that the whole title would mean something

like "chief of the camp." A modern Japanese scholar has suggested that the

title Ao-lo Po-chi-lieh refers to Khabul khan, the grandfather of Chinggis

khan, who indeed, as the

Secret history

of

the Mongols

tells us, "ruled over all

the Mongols."

10

In other words, it seems that around 1146—7 the chieftain of the Mongols

had become an "outer vassal" of the Chin state and had been accorded a title

appropriate to his rank. It should not surprise us that both the

Secret history

and the

Yuan-shih

(Yuan history) remain silent on this episode. The

Chin shih

(Chin history) also omits to mention it, perhaps because it was compiled

under the Mongolian Yuan dynasty and therefore tended to pass in silence

over anything that could point to a vassal status of the Mongols under the

predecessors of Chinggis khan. It is also significant that all our information

on these early Mongolian-Chin relations comes from Sung sources, which

did not have to consider political prohibitions imposed by Mongolian rule.

In any case it remains a fact that after 1146 the Mongols had already

become a major power in the steppe regions that the Liao government had

formerly found difficult to control. This was to some extent a political

configuration similar to that a generation earlier when the Jurchens them-

selves had been vassals of the Liao on their eastern frontier and tried to win

formal and factual independence from their overlords. At the same time, in

1146,

the Chin tried to win the allegiance of the Western Liao or Khara

Khitai, who under Yeh-lii Ta-shih had founded an empire in Central Asia.

But this diplomatic initiative failed completely, and the chief envoy was

killed on his way to the far west. This same envoy had successfully estab-

9 This agreement with the Mongols is not mentioned in the Chin sbib, but it appears in Yii-wen Mou-

chao,

Ta Chin kuo chih (KHCPTS, ed.), 12, pp. 99—100; and in Li Hsin-ch'uan, Chien-ytn i lai

ch'ao

yeh tsa chi (KHCPTS ed.), 19, p. 591.

10 Jicsuzo Tamura, "The legend of the origin of the Mongols and problems concerning their migration,"

Ada Asiatica, 24 (1973), p. 12.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE POLITICAL HISTORY

OF

CHIN AFTER II42

239

lished relations in 1144 with the Uighurs to the west of the Hsi Hsia state.

Unlike Sung, Kory6, and Hsi Hsia, however, the Uighurs did not send

regular courtesy embassies for the New Year festival and the emperor's birth-

day every year but appeared only irregularly to pay homage to the Chin with

an offer of local products.

The situation of Chin in the intricate multistate system of East Asia was

thus firmly established. What created an element of instability was the Chin

emperor's own personality. Apart from his conduct he seems to have suffered

from persecution mania and repeatedly had high officials and even members

of his own clan killed on flimsy pretexts. Inevitably a faction developed

against him, and finally the conspirators murdered him on 9 January 1150.

The conspiracy was headed by the emperor's cousin Ti-ku-nai, whose Chinese

name was Wan-yen Liang (1122-61). He was duly enthroned as emperor,

but the Chin shih does not recognize him as such; the sources always refer to

him as prince of Hai-ling, Hai-ling wang, and in 1180, many years after his

death, he was even posthumously demoted to the rank of a commoner.

The Hai-ling wang

episode

In the rogues' gallery of Chinese rulers, Hai-ling wang occupies a place of

honor. Sung and Chin sources alike describe him as a bloody monster.

Indeed, in this respect he proved far worse than Hsi-tsung had ever been. For

him it became standard procedure to murder his opponents, including those

from the imperial clan

itself.

The fact that he transferred the wives and

concubines of the murdered princes into his own harem added, in the eyes of

Chinese historians, lechery to bloodthirstiness. In later centuries he even

became an antihero in popular pornography, where his exploits are embel-

lished with gusto. But it would be wrong to judge his personality from the

point of view of the moralizing sources alone. Hai-ling wang was in fact a far

more complicated person than the cruel and ruthless usurper he appears to

have been at first sight. There was method and purpose behind his seemingly

senseless acts of violence. He marks the last phase of transition from a more

collective and clan-dominated leadership to monarchic autocracy. At the

same time he was, strange as it may sound, a great admirer of Chinese

civilization, and some part of his ruthless extermination of Jurchen grandees

can be interpreted as a fight against the advocates of the old tribal and feudal

ways of

life.

Another motivation was the elimination of Wu-ch'i-mai's descen-

dants because he wanted to keep the succession to the throne in A-ku-ta's

lineage. Hai-ling wang was an avid reader and had studied the Chinese

classics and histories. Greatly impressed by the many Sung Chinese whom he

had met after the resumption of diplomatic relations and by their ways, he

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

240 THE CHIN DYNASTY

had adopted such typically Chinese customs as playing chess and drinking

tea, so that in his youth he had been given the nickname of Po-lieh-han, a

Jurchen phrase meaning something like "aping the Chinese."

11

Under Hai-ling wang's rule, many reforms that tended to sinify the

Jurchen state and society were introduced, in ritual and ceremony as well as

in fiscal policy and administration. No longer content with the fact that the

political center of the Jurchen state was still to a large extent in the under-

developed region of Manchuria, he began to shift the existing central agen-

cies to the south. Yen-ching (Peking), which had hitherto been the Southern

Capital, was reconstructed, and new palaces were built there. In 1152 Hai-

ling wang took up residence in Yen-ching and had it renamed the Central

Capital. Some years later, in 1157, he even ordered the destruction of the

palaces and mansions of the Jurchen chiefs in the Supreme Capital in north-

ern Manchuria and had the status of the town reduced to that of a simple

prefecture. He also gave orders to build an imperial residence in K'ai-feng,

the former Sung capital, and made it his Southern Capital.

All this shows how much Hai-ling wang wanted to become a Chinese ruler

instead of a Jurchen leader. But his aspirations went beyond the sinification

of

his

realm. He regarded himself as the potential overlord of all of China and

considered his legitimacy as the ruler of China to be as good as that of the

Sung. After eliminating, chiefly through murder, those of his opponents who

were in favor of continuing the coexistence policy with Sung, Hai-ling wang

began preparations for a new war of conquest. His pretexts were not subtle:

In 1158 he accused the Sung of violating the 1142 treaty by illicitly purchas-

ing horses at the border markets.

From 1159 on, Hai-ling wang thoroughly organized preparations for an

all-out attack against Sung. In order to eliminate a possible diversion by

unrest on the border with Hsia, the minister of war

was

dispatched to inspect

the border and its delimitation. Horses were requisitioned in great numbers;

the total is reported to have been 560,000 animals. A huge store of military

weapons was brought together and provisionally stored in the Central Capital

(Peking). The emperor, having realized that a huge campaign could not take

place with the Jurchen soldiers alone, ordered the registration of Chinese

soldiers throughout the whole country. Such measures met with local resis-

tance by the Chinese population and the Chin shih records several minor

revolts led by Chinese, particularly in the southeastern region, which bor-

dered on Sung. The recruitment among the population continued until the

summer of 1161.

Hai-ling wang had also foreseen that an advance into the Sung territory

11 Ta Chin kuo chih, 13, p. 103.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008