The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

HSIA COMES OF AGE: CH'UNG-TSUNG AND JEN-TSUNG 2OI

arrogation of power, as such honors were normally reserved for meritorious

royal scions. Later that year the chief minister reportedly denounced the

newly established schools as useless Chinese institutions inappropriate to

Hsia society, wasting meager resources in the support of parasitic scholars.

Jen-tsung's response to this attack on his closest associates, the scholars and

monks, is unknown, but Jen Te-ching was clearly defeated, for the schools

remained intact. In 1161 the emperor went further and also established the

Han-lin Academy to compile the dynasty's historical records. This inner-

palace agency, along with the Censorate and the schools, became centers of

opposition to the chief minister, whose domains in the Secretariat and Mili-

tary Bureau were moved outside the inner court in 1162.

97

In

1161-2

Hsia became peripherally involved in the Chin war against the

Sung. The Sung authorities in Szechwan tried unsuccessfully to solicit

Tangut support against

the

Jurchens,

while Hsia troops briefly occupied both

Sung and Chin territories in Shensi, which Hsia claimed as its own. Jen Te-

ching probably had a hand in these activities, considering his control over the

army and his subsequent efforts to enlist the support of Szechwan officials for

his private schemes.

From 1165 to 1170 the chief minister labored to create for himself an

independent satrapy in northern Shensi and the Ordos, with his headquarters

at Ling-chou and the nearby Hsiang-ch'ing Army Superintendancy. He fur-

ther meddled in the troubled affairs of some Chuang-lang (Hsi-fan) tribes

whose homeland now unhappily straddled the ill-defined border region be-

tween Sung, Chin, and Hsia in the T'ao River

valley.

In the event, a jurisdic-

tional dispute arose between Chin and Hsia, presaging the unrest that would

engulf this area in the early thirteenth century. Jen Te-ching then tried

without success to curry favor with the Chin emperor, Shih-tsung (r. 1161 —

89),

who shrewdly parried the minister's veiled overtures. Finding no encour-

agement in that quarter, Jen Te-ching began to exchange secret messages

with the Sung pacification commissioner in Szechwan. A Hsia patrol cap-

tured one of the latter's agents carrying a letter to the chief minister and

forwarded the incriminating document to his emperor, who passed it on to

the Chin court.

98

Before obtaining this firm evidence of the Hsia minister's treachery, the

Chin ruler had received reports from captured Sung spies, among others, of

suspicious activity along his southwestern border. The Chin court also

learned that Jen Te-ching had sent a large number of troops and laborers to

97 SS, 486, p. 14025; Wu, Hsi Hsia shu shih, 36, pp. I3b-i4b.

98 On the Chuang-lang, see CS, 91, pp. 2016—18. On Hsia contact with Szechwan, see SS, 34, pp.

643-4;

486, p. 14026; Chou Pi-ta (1126—1204),

Wen-cbang

chi (Chou l-kuo

Wen-chung

kung wen chi)

(SKCP

ed.) 61, pp. I7b—i8a; 149, pp. i6a-i7a; and

CS,

61, p. 1427.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2O2 THE HSI

HSIA

repair

and

fortify Ch'i-an-ch'eng (the former Chi-shih), the Tangut outpost

in Chuang-lang territory. Shih-tsung dispatched officials

to

investigate,

but

they were too late

to

halt the construction and unable to confirm rumors of

a

Sung-Hsia conspiracy.

In

reply

to

their inquiry,

the

Tanguts (i.e.,

Jen

Te-

ching himself) asserted the purely defensive nature of the fortifications."

The death of Jen Te-ching's daughter, the empress dowager Jen,

in 1169

or 1170, supposedly spurred the chief minister to

pressure

Jen-tsung to grant

him

the

eastern half

of

the country,

a

statelet that he named Ch'u. To ratify

the deed, Jen Te-ching further persuaded his sovereign to request a patent of

investiture

for him

from

the

Chin court.

The

Chin emperor Shih-tsung

expressed his profound disapproval of the whole affair and privately wondered

why

the

Hsia ruler could

not

discipline

his

unruly subject.

He

denied

the

patent, returned

the

embarrassed embassy's gifts,

and

promised

to

send

an

official investigation. This proved unnecessary.

In the eight month

of

1170 Jen-tsung's own men secretly rounded up and

executed

the

chief minister,

his

clan,

and his

adherents.

A

Hsia delegation

delivered

a

letter

of

gratitude from Jen-tsung

to

the Chin emperor, politely

averring that no further assistance would be required, except to maintain

the

peace

and

integrity

of

their common border

in the

area where

the

former

minister had caused clashes with the Tibetans.

100

Even without any reliable sources regarding Jen Te-ching,

it

is possible

to

venture some explanations

of

the episode, and especially of Jen-tsung's con-

duct. First, the Tangut emperor was not an absolute monarch; he was subject

to

the

restraining influence

of

traditional tribal practices.

One

important

institutional restraint was

the

special position

of

the chief counselor, espe-

cially when he was a member of the consort clan (which may or may not have

been

the

case here). Both

in

Tibet

and

among the Uighurs, chief ministers

wielded significant powers,

and the

influence

of

their models

on

Tangut

government

is

beyond doubt.

101

Another important point

is

that Jen-tsung was

the

first Tangut emperor

who

did not

grow

up on the

battlefield

and who did not

cultivate close

personal ties with

the

army. Instead

he

delegated control

of

military affairs

first to

his

uncle Wei-ming Ch'a-ke

and

then

to

Jen Te-ching.

For a

long

time this was

a

convenient,

and

from

a

military point

of

view,

a

successful

arrangement.

But

when need arose,

the

emperor had

to

look elsewhere

for

support; he could not challenge the military head-on.

99 CS, 91, p. 2017-18.

100 CS, 134, p. 2869—70; Wu,

Hsi

Hsia

shu

shih, 37, p. 13a.

101 See Sato Hisashi,

Kodai Cbibetto

shi kenkyu (Kyoto, 1958—9), vol. 2, pp. 11—14, 28-9, 711-38;

Elizabeth Pinks,

Die

Uiguren

von

Kan-chou

in

dtr frubcn Sung-Zeit,

pp.

106—7,

'

'4~'5J Abe Takeo,

"Where

was the

capital

of the

West Uighurs?"

in the

Silver jubilee volume

of

the Zimbuti kagaku

kenkyusho (Kyoto, 1954),

pp.

439—41.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HSIA COMES OF AGE: CH'UNG-TSUNG AND JEN-TSUNG 203

Jen-tsung apparently found that support in the educational and cultural

institutions in which he had been raised and that he fostered all of his life. He

cultivated the civilian norms of Confucianism and propagated the imperial

persona of an aspiring Bodhisattva. Jen-tsung's patronage of Buddhism and

cultivation of

bodhichitta

(enlightened mind) are nowhere alluded to in Chi-

nese chronicles, but extensive Tangut materials reveal the magnitude and

significance of his Buddhist activities, activities that, after all, were the

traditional occupation of every Tangut ruler. That Jen-tsung busily engaged

in accumulating good merit to attract support, to heighten and display his

prestige and moral authority, and thus to undermine his rival in no way

•

diminishes his religious sincerity. He waged an ideological battle with Jen

Te-ching in which he held all the weapons and ultimately forced his minister

into treachery, repudiating the very values that he needed to legitimize

himself as an independent ruler. When Jen-tsung's minister was finally

exposed as a traitor, his elimination was a routine matter; whatever justifi-

ably frustrated elements had banded to his cause now deserted him.

There certainly existed an impulse to split up the Tangut empire into a

Chinese-oriented Ordos state and a steppe-oriented Ho-hsi state. This im-

pulse reflected deep-rooted geopolitical and cultural realities, not simply a

tribal tendency toward decentralization. But ultimately much stronger was

the contrary impulse to maintain the integrity of the realm, which sprang

from another overarching geopolitical reality: the existence of a system of

interstate relations in which Hsia, Sung, and Liao (later replaced by Chin)

acted as a stable tripod of power in continental East Asia. Neither Sung or

Chin would tolerate the creation of another independent kingdom in north

China; witness the earlier failure of Chin to rule north China through its

puppet regimes of Ch'i or Ch'u.

If Jen Te-ching represented a conservative element in Hsia society discon-

tented with the direction of change in government policies, Jen-tsung, on the

other hand, embodied the

firmly

entrenched legitimacy of Wei-ming dynastic

rule and the established territorial integrity of the state. His rule represented

a

civilian government headed by

a

semidivine Buddhist ruler, and his power was

based on a compromise with the military establishment (i.e., with the tribal

aristocracy) by which hereditary privileges were confirmed by the state, in

exchange for loyalty to the throne."" Many of these points

are

elaborated in the

Tangut law code: "The revised and newly endorsed code of law of the age of

102 See, for example, the argument in Shimada Masao,

Ryocho

kansii

no

kinkyQ,

Toyo hoshi ronshu no. 1

(Tokyo: Sobunsha, 1978), English summary. One of the first scholars to comment on the Buddhist

aspect of Tangut rulers was Paul Serruys, "Notes marginales sur le folklore des Mongols Ordos," Han

Him:

Bulletin du

centre

d'ttuda

Sinologiques

de Pikin, 3, nos. 1—2 (1948), p. 172. On the Buddhist-

inspired native honorifics for Hsia emperors, see Pu P'ing, "Hsi Hsia huang ti ch'eng hao k'ao," pp.

70-82.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

204 THE HSI HSIA

celestial prosperity"

(T'ien-sbeng chiu

kai hsin ting

chin

ling),

which, perhaps not

coincidentally, was issued at the end of the T'ien-sheng reign period (1149—

70),

about the time of Jen Te-ching's execution.

IO3

The man who succeeded Jen Te-ching as the dominant minister, Wo Tao-

ch'ung, came from a Tangut family that for generations had supplied histori-

ographers to the Tangut court. A Confucian scholar and teacher of Tangut

and Chinese, Wo Tao-ch'ung translated the Lunyii (Analects) and provided it

with a commentary, also in Tangut. He wrote as well, in Tangut, a treatise

on divination, a topic of enduring interest to the Tanguts. Both works were

published during his lifetime and were still extant during the Yuan period.

Upon Wo Tao-ch'ung's death Jen-tsung honored him by having his portrait

painted and displayed in all the Confucian temples and state schools.

IO4

The Tangut emperor Jen-tsung was a superb propagandist who, like his

Jurchen counterpart Shih-tsung, mastered the public role of a virtuous ruler.

But whereas Chin Shih-tsung gained the Confucian reputation of a "Little

Yao or Shun," Jen-tsung's path to perfection is strewn with allusions to

Buddhist sainthood.

IO5

Jen-tsung oversaw and participated in the editing and

revision of all the Buddhist translations undertaken at the courts of his

predecessors. Thus, although it was further refined in the Yuan period, by

the end of his reign the Tangut Tripitaka was virtually completed and was

printed in its entirety early in the fourteenth century.

106

Religious zeal prompted the emperor's most eloquent and extensive propa-

ganda acts. Throughout his reign the emperor and members of his family,

notably his second consort empress

Lo

(who

was

of Chinese

descent),

sponsored

massive printings and distributions of favorite Buddhist texts on various com-

memorative occasions. The most spectacular of these publications occurred in

1189.

Celebrations in that year honoring the fiftieth anniversary of Jen-tsung's

103 See n. 87.

104 Yii Chi (1272

—1348),

Tao-yiian

bsiieb

ku lu (KHCPTS ed.) 4, pp. 83—4; Ch'en Yuan,

Western

and

Central Asians in China under

the

Mongols:

Their

transformation

into

Chinese,

trans. Ch'ien Hsing-hsi and

L.

Carrington Goodrich (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1966), p. 128, in which the surname Wo is

misread as Kuan; Wu Chi-yu, "Sur la version tangoute d'un commentaire du

Louen-yu

conserved a

Leningrad," T'oungpao, 55 (1969), pp. 298—315.

10;

See, for example, Nevskii Tangutsiaia filologiia, vol. 1, p. 82; and the text of Jen-tsung's dedication

to a newly restored bridge over the Hei-shui in Kansu, in Wang Yao, "Hsi Hsia Hei-shui ch'iao pei

k'ao pu," Chung yang min tsu htiiih yuan

hsu'eh

pat, 1 (1978), pp. 51—63. This stele inscription is

registered in Chung Keng-ch'i, comp., Kan-choufuchih(1779; repr. in Chung-kuofangchihts'ungsbu:

Hua-pei ti fang no. 56i;Taipei, 1976), 13,pp.

1

ib—12a, but did not come to the attention of either

Wu Kuang-ch'eng or Tai Hsi-chang. Jen-tsung's dedication is translated from the Chinese by E.

Chavannes, "Review of A. I. Ivanov: Stranitsa iz istorii Si-sia (Une page de l'histoire du Si-hia;

Bulletin de I'Academie imperiale des sciences de Saint-Peiersbourg, 1911, pp. 831-836),"

T'oung

pao,

12 (1911), pp. 441—6.

106 Wang Ching-ju, Hsi Hsia yen

chiu,

vol. 1 (Peking, 1932), pp. 1—10; Heather Karmay, Early Sino-

Tibetan art (Warminster, 1975), pp. 35—45. On Tangut Buddhist activities and the Tangut Tripitaka

before and after 1227, see Shih Chin-po, Hsi Hsia wen hua, pp. 64—105.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE HSIA STATE AND THE MONGOLIAN CONQUEST 205

accession were highlighted by the printing and distribution of 100,000 copies

of

the

Kuan

Mi-le

p'u-sa

shang

sheng Tou-shuai t'ien ching (Sutra

on the

visual-

ization of the Maitreya Bodhisattva's ascent and rebirth in Tushita Heaven) and

50,000 copies of several other sutras, printed in both Tangut and Chinese.

The year 1189 was a year of changes in East Asia; it also saw the death of

Chin Shih-tsung and the abdication of

Sung

Hsiao-tsung. Hence the Tangut

ruler had cause for a liberal demonstration of his gratitude to the Buddha.

Despite occasional incidents with the Jurchens, peace had prevailed for most

of his long reign. In general the two courts maintained fairly cordial rela-

tions,

though some disagreements did arise, increasingly so toward the end of

the twelfth century, because of

economic

and minor territorial disputes.

The

Jurchens charged that at border markets the Tanguts traded worthless

gems and jades for their good silk textiles, recalling Northern Sung com-

plaints about Khotanese envoys flooding Chinese markets with poor jade.

Consequently, the Chin closed the border markets at Lan-chou and Pao-an in

1172 and did not reopen them until 1197. Next complaints arose of illegal

trafficking across the Shensi border, so that the Sui-te market was also shut,

leaving only a market at Tung-sheng and one at Huan-chou. Drought and

famine had swept north China in the 1170s; Tangut border raids increased

during the same period, culminating in 1178 with a Tangut sack of Lin-chou

(which was now in Chin hands). In 1181 the Chin emperor finally reopened

the Sui-te market and granted three-day trading privileges to Tangut envoys

visiting the Chin capital.

107

In 1191 some Tangut herdsmen strayed into Chen-jung prefecture and

were chased by a Chin patrol, which they took captive. They then ambushed

and killed a pursuing Jurchen officer. Jen-tsung refused to extradite the

guilty parties, assuring the Chin that he had already punished them.

These, however, were comparatively minor disturbances of generally peace-

ful relations. After the deaths of Shih-tsung of Chin in 1189 and Jen-tsung in

Hsia in 1193, however, the short reigns of their respective successors proved

to be the prelude to an era of internal disorder and conflict between the

states,

the principal cause of which was the growing power and unification of

the Mongols under Temujin (the future Chinggis khan).

THE LAST YEARS OF THE HSIA STATE AND THE

MONGOLIAN CONQUEST

When Jen-tsung died in 1193 at the age of seventy, his eldest son by Empress

Lo,

Ch'un-yu (Huan-tsung; r. 1193—1206), ascended the throne at the age of

107 CS, 134, pp.

2870-1;

Yii-wen Mou-chao (13th c), Ta Chin kuo

chih

(KHCPTS ed.), 17

passim.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2o6 THE HSI HSIA

seventeen. Very little is known about Huan-tsung's reign, but certainly the

most crucial event came with the first Mongolian raid into Hsia territory in

1205.

From 1206 until its destruction in 1227 by Chinggis khan, the Tangut

royal house endured a period of unprecedented instability. But neither inter-

nal decay nor inherent weakness finally undid the dynasty. Rather, the Hsia

state,

like its more powerful neighbors, was destroyed by the Mongols, the

new steppe power whose emergence fatally destabilized the Sung—Chin—Hsia

balance of power in East Asia. Anti-Chin and anti-Mongolian factions

formed at the Hsia court, with usurpation and abdication occurring for the

first time in the state's history.

Since the 1170s, stirrings from the steppe had occasionally affected Hsia

and Chin and appear in the official records. One reason that the Jurchens

closed three of their western border markets with Hsia was their suspicion of

the Tanguts' espionage activities and their possible dealings with the Khara-

Khitai far to the west, which they considered hostile to Chin interests.

108

It

is also known that a Kereyid prince who was overthrown by Temiijin's father,

probably in the 1170s, found refuge in Hsia, never to be heard of again.

Another Kereyid prince reportedly spent some time in exile among the

Tanguts, who favored him with the honorary epithet of Jakha Gambu

(roughly, "elder state counselor"), by which name he is known to posterity.

Jakha Gambu's fickle loyalties were tolerated by Temiijin because his brother

To'oril (Ong khan) was Temvijin's own sworn father and because Temiijin's

family took several of Jakha Gambu's daughters in marriage. One of them,

the famous Sorghaghtani Beki, mothered Mongke, Khubilai, and Hiilegii.

Another of Jakha Gambu's daughters evidently married the Tangut king, and

her beauty is said to have inflamed Chinggis khan in his final onslaught

against the Tangut country.

109

It seems possible, then, that the Tangut ruling

house had already entered into the steppe network of marriage alliances,

which might help explain their special status later in the Mongolian empire.

The Kereyid connection with Hsia did not end there. After To'oril's

eventual defeat by Temiijin in 1203, the Kereyid leader's son, Ilkha

Senggiim, fled through Edzina to northeast Tibet, whence he was driven to

the Tarim basin and finally killed by a local

chief.'

IO

Although the Tangut

108 CS, 50, p. 1114;

SS,

486, p. 14026.

109 Rashid al-DIn,

Sbornik

letopiiei,

vol. i, pt. 2, trans. O. I. Smirnova(Leningrad, 1952), pp. 109-10,

127;

Paul Pelliot and Louis Hambis, trans., Hiiloire da campagna de Gengis Khan, Cbthg-wou Ti'in-

Tcheng

Lou (Leiden, 1951), pp. 230, 261; Iurii N. Rerikh (George N. Roerich), "Tangutskii titul

dzha-gambu Kereitskogo," Kratkiesoobsbcbeniia iiutituta

narodov

Azii, 44 (1961), pp. 41-4.

no Rashid al-DIn, Sbornik letopisti, vol. i,pt.2,p. 134; Sbengwuch'in chengluchiaochu, in Meng-kusbib

liao ssu cbung, ed. Wang kuo-wei (Peking, 1926; repr. Taipei, 1962, 1975), p. 107. The notice in

Sung Lien et al., eds., Yiian

shih

(Peking, 1976), i,p. 23 (hereafter cited as YS) is misplaced under

the year 1226 as an explanation for Chinggis's invasion in that year.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE HSIA STATE AND THE MONGOLIAN CONQUEST 207

authorities had apparently refused to grant refuge to the Kereyid fugitive, his

flight across Tangut territory became the pretext for a Mongolian attack on

Ho-hsi in 1205. Several fortified settlements were plundered and many cattle

taken away.'' *

In 1206 Temiijin was proclaimed Chinggis khan, and a coup in Chung-

hsing brought a new ruler to the Tangut throne. Huan-tsung was deposed by

a cousin, Wei-ming An-ch'iian (Hsiang-tsung; r. 1206-11), and died in

captivity a month later. Grand Empress Dowager Lo was coerced into per-

suading the Chin court to grant the usurper a patent of investiture.

112

Thereafter she disappears from the record, presumably dispatched to a monas-

tic retirement.

The following year Chin lost the allegiance of

the

Onggiid and the tribally

mixed border guards

{jiiyin;

Chinese:

chiu)

on their northwest frontier, and

the nearby Tangut garrison of Wu-la-hai was sacked by the

Mongols.

"3

The

Mongols could now invade with impunity both Shansi and the Ordos.

The Mongolian raiding party did not withdraw from Wu-la-hai until spring

of

1208.

The Hsia sent a succession of embassies to the Chin capital, presum-

ably seeking a united front against the Mongolian advance, but unfortunately

for both states, the Chin monarch died that winter without an heir and was

succeeded by a far less competent relative known to history as Wei-shao wang

(deposed in 1213). This prince refused to cooperate with the Tanguts and is

said to have commented: "It is to our advantage when our enemies attack one

another. Wherein lies the danger to us?"

1

'

4

Whatever actually happened,

Tangut—Jurchen relations deteriorated rapidly from this point onward.

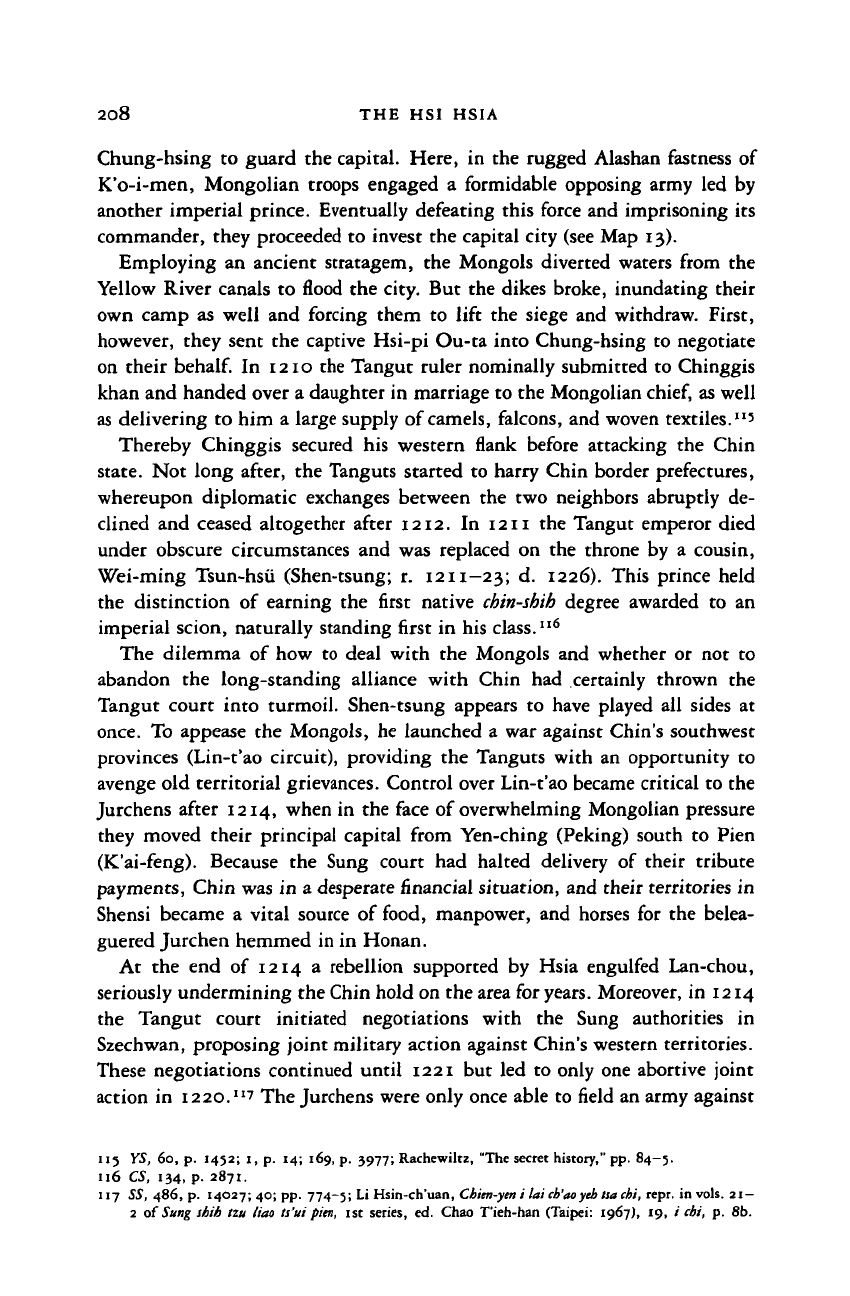

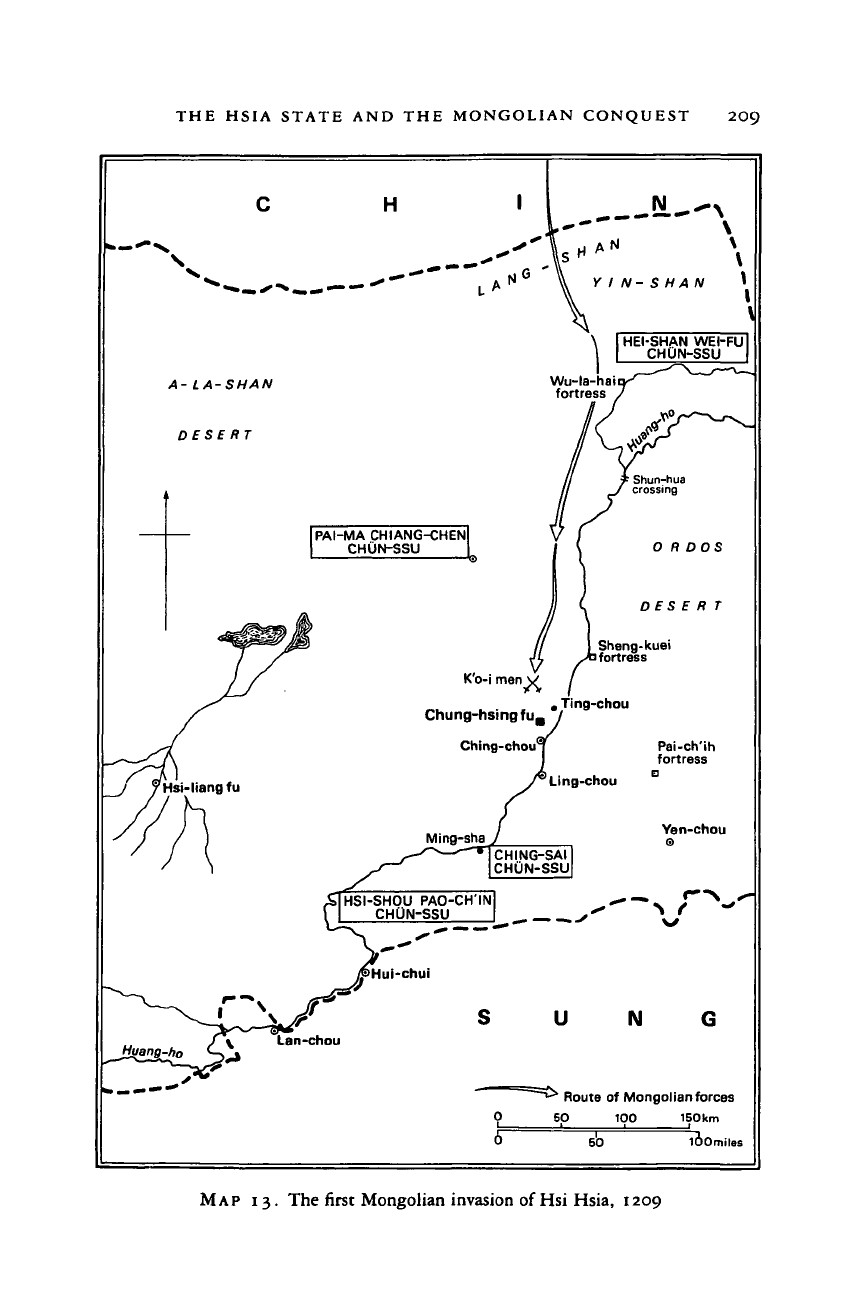

In the autumn of 1209, after receiving the voluntary submission of the

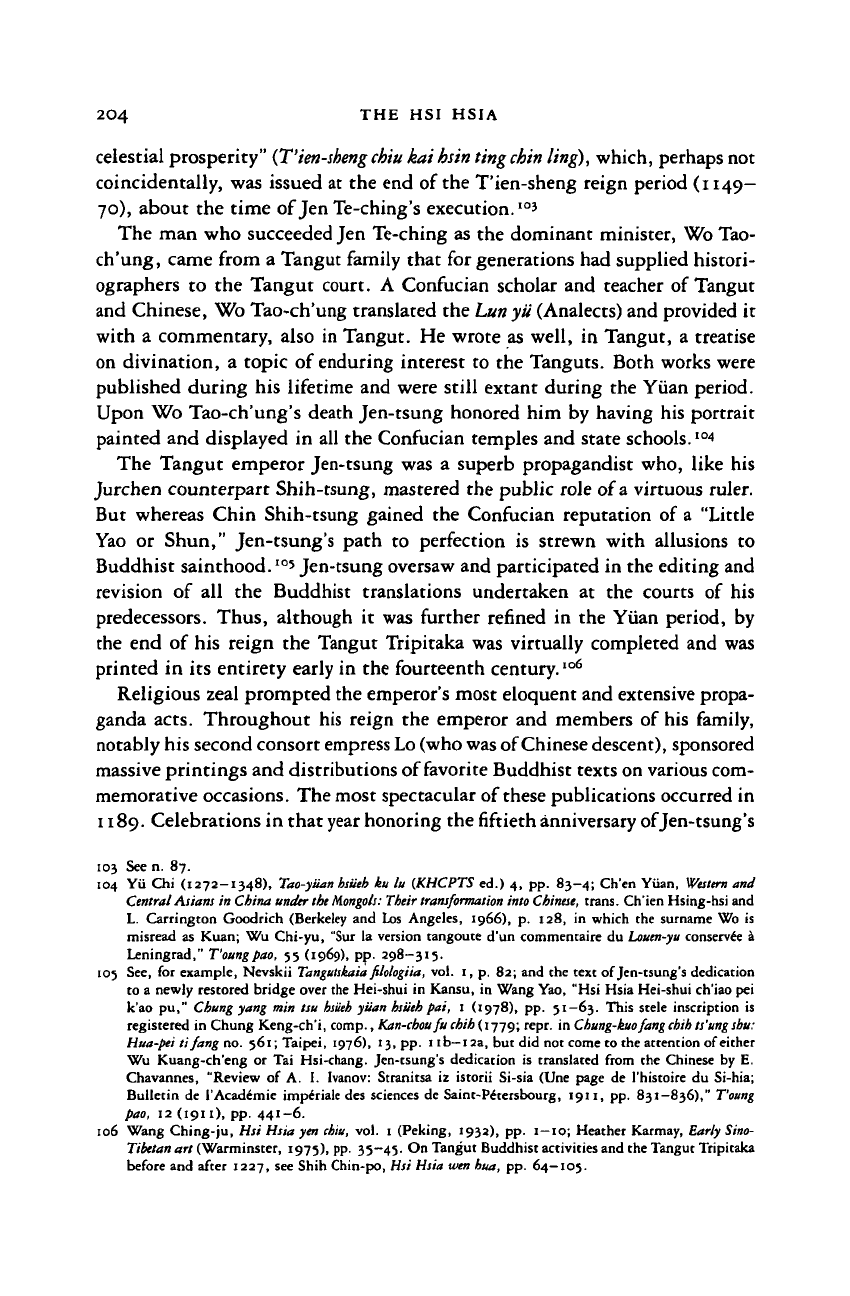

Uighurs of Turfan, Chinggis khan launched a major invasion of

Hsia.

Enter-

ing Ho-hsi through a pass "north of Hei-shui-ch'eng and west of Wu-la-hai-

ch'eng," Mongolian troops overcame a Tangut army led by an imperial prince

and captured its deputy commander. Advancing to Wu-la-hai, the Mongols

again overwhelmed that garrison, whose commander surrendered, and took

prisoner a high official called Hsi-pi Ou-ta. From Wu-la-hai the Mongolian

army turned south and marched to K'o-i-men, the garrison situated west of

in Wu Kuang-ch'eng's tale that becuase of their deliverance from the Mongolian menace on this

occasion the Tanguts changed the name of their capital from Hsing-ch'ing to Chung-hsing, must,

however, be rejected as a fiction. See n. 46; YS, i,p. 13; Rashld al-Dln,

Sbornik

Utopiiti, vol. i,pt.

2,

p. 150;

Sbeng

wu

ch'in cbeng

lit

chiao

chu,

p. 118.

112 CS, 134, p. 2871.

113 Paul Buell, "The role of the Sino-Mongolian frontier zone in the rise of Cinggis Qan," in Studies on

Mongolia:

Proceedings

of

the

first North American

Conference

on

Mongolian

studies,

ed. Henry G. Schwarz

(Bellingham, 1979), pp. 66—8. See also Igor de Rachewiltz's comments on the Jiiyin

(chiu)

troops in

"The secret history of the Mongols: Chapter eleven,"

Papers

on Far

Eastern

History, 30 (1984), pp.

105-7.

114 CS, 62, p. 1480; 12, p. 285; see Ta Chin kuo chih, 21, pp. 23-4, for the Jurchen ruler's remark.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2O8 THE HSI HSIA

Chung-hsing to guard the capital. Here, in the rugged Alashan fastness of

K'o-i-men, Mongolian troops engaged a formidable opposing army led by

another imperial prince. Eventually defeating this force and imprisoning its

commander, they proceeded to invest the capital city (see Map 13).

Employing an ancient stratagem, the Mongols diverted waters from the

Yellow River canals to flood the city. But the dikes broke, inundating their

own camp as well and forcing them to lift the siege and withdraw. First,

however, they sent the captive Hsi-pi Ou-ta into Chung-hsing to negotiate

on their

behalf.

In 1210 the Tangut ruler nominally submitted to Chinggis

khan and handed over a daughter in marriage to the Mongolian

chief,

as well

as delivering to him a large supply of

camels,

falcons, and woven textiles."

3

Thereby Chinggis secured his western flank before attacking the Chin

state.

Not long after, the Tanguts started to harry Chin border prefectures,

whereupon diplomatic exchanges between the two neighbors abruptly de-

clined and ceased altogether after 1212. In 1211 the Tangut emperor died

under obscure circumstances and was replaced on the throne by a cousin,

Wei-ming Tsun-hsu (Shen-tsung; r. 1211-23; d. 1226). This prince held

the distinction of earning the first native

chin-shih

degree awarded to an

imperial scion, naturally standing first in his class.

1

'

6

The dilemma of how to deal with the Mongols and whether or not to

abandon the long-standing alliance with Chin had certainly thrown the

Tangut court into turmoil. Shen-tsung appears to have played all sides at

once.

To appease the Mongols, he launched a war against Chin's southwest

provinces (Lin-t'ao circuit), providing the Tanguts with an opportunity to

avenge old territorial grievances. Control over Lin-t'ao became critical to the

Jurchens after 1214, when in the face of overwhelming Mongolian pressure

they moved their principal capital from Yen-ching (Peking) south to Pien

(K'ai-feng). Because the Sung court had halted delivery of their tribute

payments, Chin was in a desperate financial situation, and their territories in

Shensi became a vital source of food, manpower, and horses for the belea-

guered Jurchen hemmed in in Honan.

At the end of 1214 a rebellion supported by Hsia engulfed Lan-chou,

seriously undermining the Chin hold on the area for

years.

Moreover, in 1214

the Tangut court initiated negotiations with the Sung authorities in

Szechwan, proposing joint military action against Chin's western territories.

These negotiations continued until 1221 but led to only one abortive joint

action in

1220.

"7 The Jurchens were only once able to field an army against

115 YS, 60, p. 1452; i, p. 14; 169, p. 3977; Rachewiltz, "The secret history," pp. 84—5.

116 CS, 134, p. 2871.

117 SS, 486, p. 14027; 40; pp. 774-5; Li Hsin-ch'uan,

Cbien-yen

i lai cb'aoycb isa chi, repr. in vols. 21—

2 of Sung shih tzu liao ts'ui

pien,

1st series, ed. Chao T'ieh-han (Taipei: 1967), 19, /' cbi, p. 8b.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE HSIA STATE AND THE MONGOLIAN CONQUEST 209

H

A-LA-SHAN

DESERT

I PAI-MA CHIANG-CHEN

CHUN-SSU

K'o-i mens/

Chung-hsingfu,

Ching-chou

HSI-SHOU PAO-CH'IN

CHON-SSU

HEI-SHAN WEI-FU

CHUN-SSU

O R DOS

DESERT

Sheng-kuei

1

fortress

, Ting-chou

Ling-chou

Pai-ch'ih

fortress

Yen-chou

*\ f "

U N

Route of Mongolian forces

SC)

100 150km

50^

lOOmiles

MAP

13. The first Mongolian invasion of Hsi Hsia, 1209

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2IO THE HSI

HSIA

Hsia, in the latter half of 1216, when Hsia gave passage to a Mongolian army

that crossed the Ordos to attack Chin territory in Shensi, and provided

auxiliary troops to assist in the Mongolian operations."

8

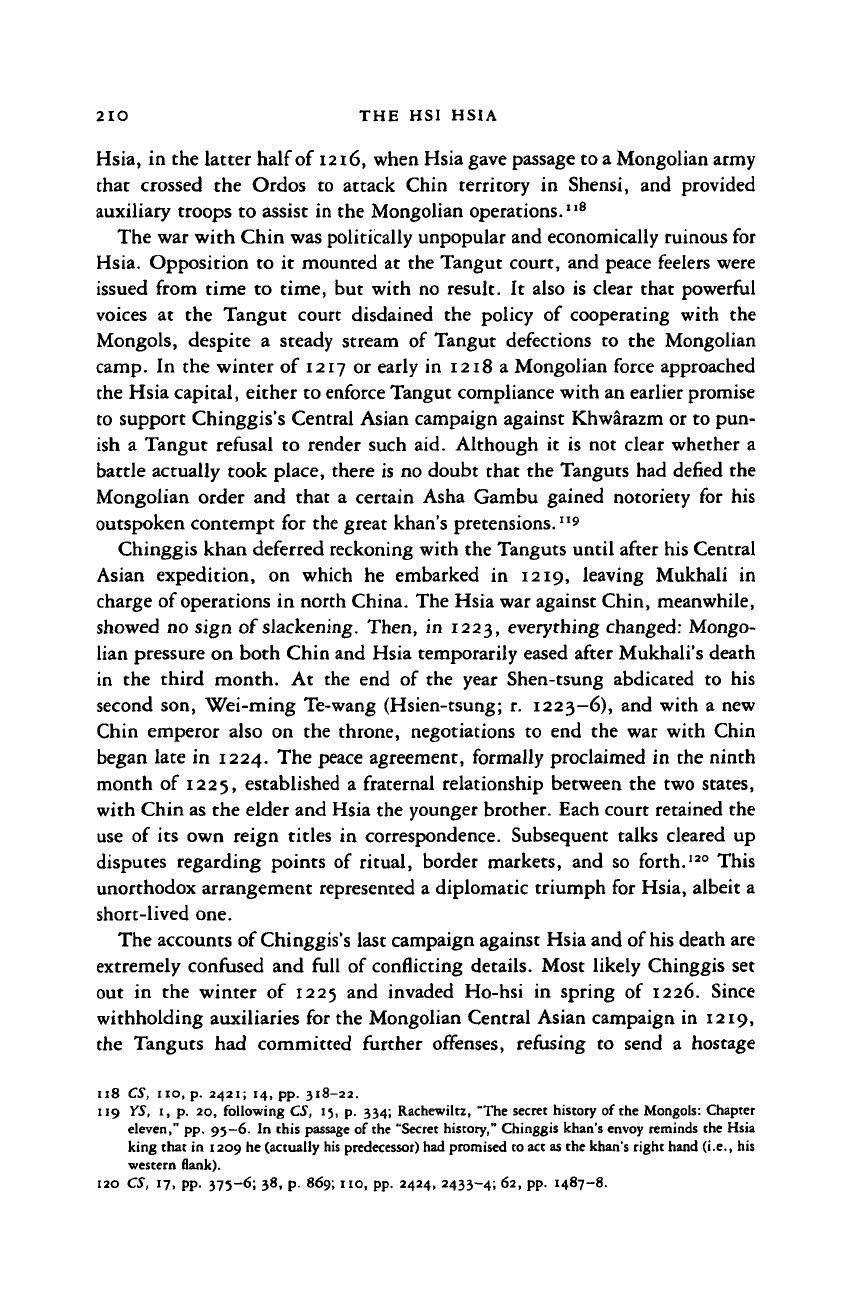

The war with Chin was politically unpopular and economically ruinous for

Hsia. Opposition to it mounted at the Tangut court, and peace feelers were

issued from time to time, but with no result. It also is clear that powerful

voices at the Tangut court disdained the policy of cooperating with the

Mongols, despite a steady stream of Tangut defections to the Mongolian

camp.

In the winter of 1217 or early in 1218 a Mongolian force approached

the Hsia capital, either to enforce Tangut compliance with an earlier promise

to support Chinggis's Central Asian campaign against Khwarazm or to pun-

ish a Tangut refusal to render such aid. Although it is not clear whether a

battle actually took place, there is no doubt that the Tanguts had defied the

Mongolian order and that a certain Asha Gambu gained notoriety for his

outspoken contempt for the great khan's

pretensions.

"9

Chinggis khan deferred reckoning with the Tanguts until after his Central

Asian expedition, on which he embarked in 1219, leaving Mukhali in

charge of operations in north China. The Hsia war against Chin, meanwhile,

showed no sign of slackening. Then, in 1223, everything changed: Mongo-

lian pressure on both Chin and Hsia temporarily eased after Mukhali's death

in the third month. At the end of the year Shen-tsung abdicated to his

second son, Wei-ming Te-wang (Hsien-tsung; r. 1223—6), and with a new

Chin emperor also on the throne, negotiations to end the war with Chin

began late in 1224. The peace agreement, formally proclaimed in the ninth

month of 1225, established a fraternal relationship between the two states,

with Chin as the elder and Hsia the younger brother. Each court retained the

use of its own reign titles in correspondence. Subsequent talks cleared up

disputes regarding points of ritual, border markets, and so forth.

120

This

unorthodox arrangement represented a diplomatic triumph for Hsia, albeit a

short-lived one.

The accounts of Chinggis's last campaign against Hsia and of

his

death are

extremely confused and full of conflicting details. Most likely Chinggis set

out in the winter of 1225 and invaded Ho-hsi in spring of 1226. Since

withholding auxiliaries for the Mongolian Central Asian campaign in 1219,

the Tanguts had committed further offenses, refusing to send a hostage

118 CS, no, p. 2421; 14, pp. 318-22.

119 YS, 1, p. 20, following CS, 15, p. 334; Rachewiltz, "The secret history of the Mongols: Chapter

eleven," pp. 95—6. In this passage of the "Secret history," Chinggis khan's envoy reminds the Hsia

king that in 1209 he (actually his predecessor) had promised to act as the khan's right hand (i.e., his

western Bank).

120 CS, 17, pp. 375—6; 38, p. 869; no, pp. 2424, 2433—4; 62, pp. 1487—8.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008