The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE POLITICAL HISTORY

OF

CHIN AFTER II42

251

Mongols for a long time, and bloody feuds had flared up between them time

and again. The Tatars were loosely allied with the Chin, but around 1190

they renounced their allegiance. A punitive expedition against them was

organized by the Chin under the imperial clansman Wan-yen Hsiang in

1196,

and the Mongols joined this campaign to take their revenge against

their old enemies. Jurchen and Mongolian forces together penetrated deeply

into Mongolia and at last, in the eighth month of 1196, succeeded in

inflicting a crushing defeat on the Tatars, whose tribal chief perished on this

occasion.

The Mongolian contingents had fought together with their allies from the

Kereyid tribe under To'oril. Their assistance in quelling Tatar power and

aspirations was rewarded by the Chin emperor; To'oril was given the rank of

prince (wang) and was henceforth known as Ong khan, whereas Temiijin (the

name by which Chinggis khan was called before his enthronement as khan in

1206) was invested with a lesser title, probably of Khitan origin. In any case

he had to regard himself from then on as an outer vassal of the Chin, although

the title he had received from the Chin court must have enhanced his prestige

among the other steppe tribes. It is self-evident that after his rise in 1206

Chinggis khan was no longer content to be treated as a Chin vassal and that he

aimed at formal independence from the Chin, however loose his vassal status

might have been. An additional motive might have been the conquest of Chin

territory, a country that must have seemed full of incredible riches to the

steppe nomads. A third motive was perhaps revenge for the death of

Ambaghai khan. Ambaghai had been proclaimed as the successor of Khabul

khan and the leader of the Mongolian federation. He was a cousin of Khabul

and the founder of the Tayichi'ud lineage of the Mongols. He, too, was on bad

terms with the Tatars, who in one of the constant raids on each other took him

prisoner and extradited him to their Chin overlords. The Chin, it seems, then

had him killed cruelly. Chinggis khan, who considered himself a legitimate

successor of Ambaghai khan as leader of the Mongols, perhaps resented the

ignominious death of Ambaghai at the hands of the Chin, but this must

remain speculative in view of the deficiency of our sources.

Finally, yet another reason for Chinggis's hatred of Chin may well have

been personal biases of the Chin ruler

himself.

When he was still a minor

Chin prince, Wei-shao wang had accepted the customary tribute presents

from Chinggis khan and, in the eyes of the Mongolian ruler, had behaved

insolently toward him. When they received an order from the ruler of Chin,

the Mongolian tribute bearers should have kowtowed before the representa-

tives of the Chin state. But when Chinggis khan learned that the new Chin

emperor was Wei-shao wang, who had earlier insulted him, he flew into a

rage and in 1210 broke off tributary relations with Chin, deciding on an all-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

252 THE CHIN DYNASTY

out attack against his Jurchen overlords.'

8

This decision was certainly

prompted by information that the Chin state at that time was suffering from

a severe famine.

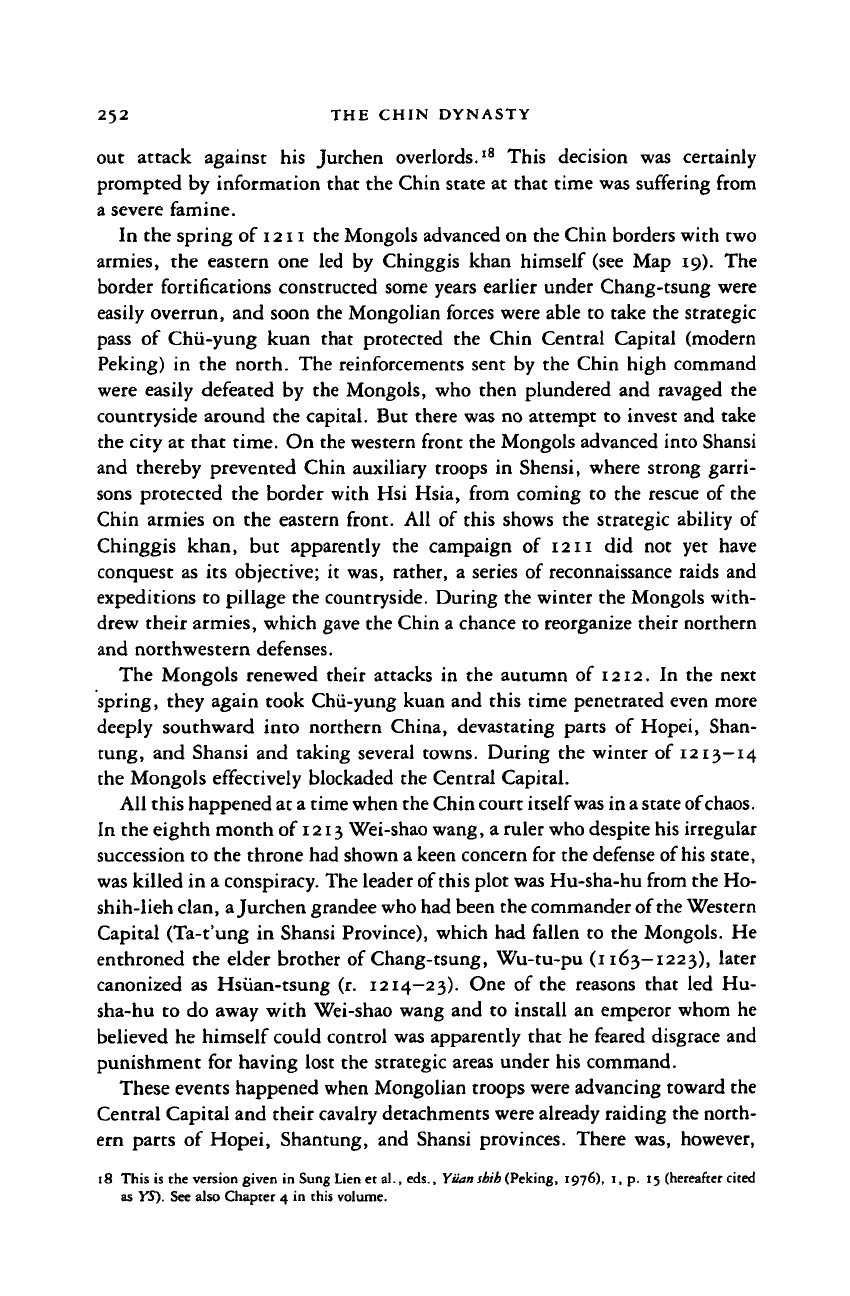

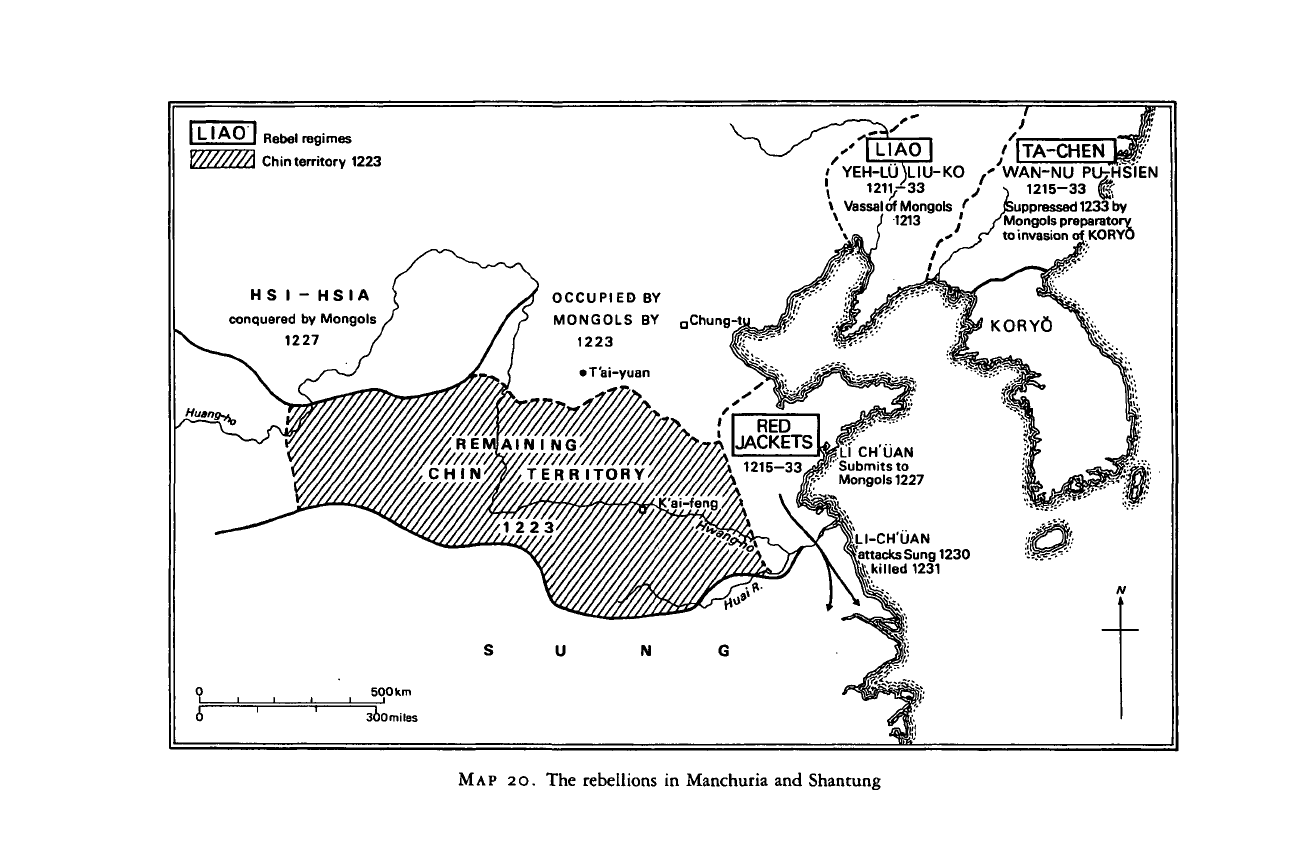

In the spring of 1211 the Mongols advanced on the Chin borders with two

armies, the eastern one led by Chinggis khan himself (see Map 19). The

border fortifications constructed some years earlier under Chang-tsung were

easily overrun, and soon the Mongolian forces were able to take the strategic

pass of Chii-yung kuan that protected the Chin Central Capital (modern

Peking) in the north. The reinforcements sent by the Chin high command

were easily defeated by the Mongols, who then plundered and ravaged the

countryside around the capital. But there was no attempt to invest and take

the city at that time. On the western front the Mongols advanced into Shansi

and thereby prevented Chin auxiliary troops in Shensi, where strong garri-

sons protected the border with Hsi Hsia, from coming to the rescue of the

Chin armies on the eastern front. All of this shows the strategic ability of

Chinggis khan, but apparently the campaign of 1211 did not yet have

conquest as its objective; it was, rather, a series of reconnaissance raids and

expeditions to pillage the countryside. During the winter the Mongols with-

drew their armies, which gave the Chin a chance to reorganize their northern

and northwestern defenses.

The Mongols renewed their attacks in the autumn of 1212. In the next

spring, they again took Chii-yung kuan and this time penetrated even more

deeply southward into northern China, devastating parts of Hopei, Shan-

tung, and Shansi and taking several towns. During the winter of 1213—14

the Mongols effectively blockaded the Central Capital.

All this happened at a time when the Chin court itself was in

a

state of

chaos.

In the eighth month of 1213 Wei-shao wang, a ruler who despite his irregular

succession to the throne had shown a keen concern for the defense of his state,

was killed in a conspiracy. The leader of this plot was Hu-sha-hu from the Ho-

shih-lieh clan, a Jurchen grandee who had been the commander of the Western

Capital (Ta-t'ung in Shansi Province), which had fallen to the Mongols. He

enthroned the elder brother of Chang-tsung, Wu-tu-pu (1163-1223), later

canonized as Hsiian-tsung (r. 1214-23). One of the reasons that led Hu-

sha-hu to do away with Wei-shao wang and to install an emperor whom he

believed he himself could control was apparently that he feared disgrace and

punishment for having lost the strategic areas under his command.

These events happened when Mongolian troops were advancing toward the

Central Capital and their cavalry detachments were already raiding the north-

ern parts of Hopei, Shantung, and Shansi provinces. There was, however,

18 This is the version given in Sung Lien et al., eds., Yiian sbib (Peking, 1976), 1, p. 15 (hereafter cited

as YS). See also Chapter 4 in this volume.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

:::;*;*;* Border of

Chin

and Hsi-Hsia V™ Mongolia

» Campaigns 1211—12 ^

'-£ Jebes

campaign

into Manchuria

---*• Campaigns 1213-14 1211-12

* Samukha's campaigns, 1216—17

Chinggis

returned

to the North after

the fall of Chung-tu, 1216-17

from

Mongolia^

1911

0211,v. n

_300km

200 miles

Hua-chou*

12tg,ix.-^—^.

Ching-chao

MAP

19. Chinggis's campaigns against Chin

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

254 THE CHIN DYNASTY

another factor besides the dissension at the Chin court that had contributed

decisively to the defeats suffered by their armies. Repeated droughts in north

China had led to widespread famine and thereby undermined the logistics of

the Jurchen war machine. In a last-minute effort the government tried to

rally all population groups against the Mongols by abandoning the existing

differentiations among the races. Military and civilian posts were opened to

Khitans and Chinese without the former numerical limitations.

In spring of 1214 the Chin sent envoys to the Mongols to ask for peace and

also offered in marriage a daughter of Wei-shao wang to Chinggis khan. The

Mongols withdrew from the Central Capital. The situation in the north

remained precarious, however, and so Hsiian-tsung decided to transfer his

court to the Southern Capital (K'ai-feng), which was not only in the center of

the agriculturally developed Chinese plains but was also protected from the

north by the Yellow River. This transfer of the capital was interpreted by

Chinggis khan as a preparation for the resumption of

war,

and so he decided

to march again against the Central Capital. On 31 May 1215 the city

surrendered to the Mongols and former subjects of the Chin such as Khitans

and Chinese who had defected to them. The capital was by far the most

populous and important city conquered so far by the Mongols in East Asia.

At about the same time, diplomatic relations between Chin and Hsia

collapsed, after many years of increasing strain, and a period of intermittent

warfare and intense hostility characterized the decade from 1214 onward.

This unfortunate development replaced the formerly good relations between

Chin and Hsia and was largely the result of factionalism and power struggles

at the courts of both states, which undermined their ability to turn back the

Mongols.

Rebellions

in Shantung

The disastrous loss of the Central Capital, a major Chin administrative center

and military stronghold, was paralleled by serious setbacks in other parts of

the state.

In 1214 the Chin had asked the Sung to deliver the payments stipulated by

the treaty of 1208 one year in advance in order to make up for losses suffered

in the past. Instead, the Sung refused to pay at all and thereby aggravated the

fiscal problems in the tottering Chin state. This coincided with the outbreak

of local rebellions in Shantung, a part of China that had throughout history

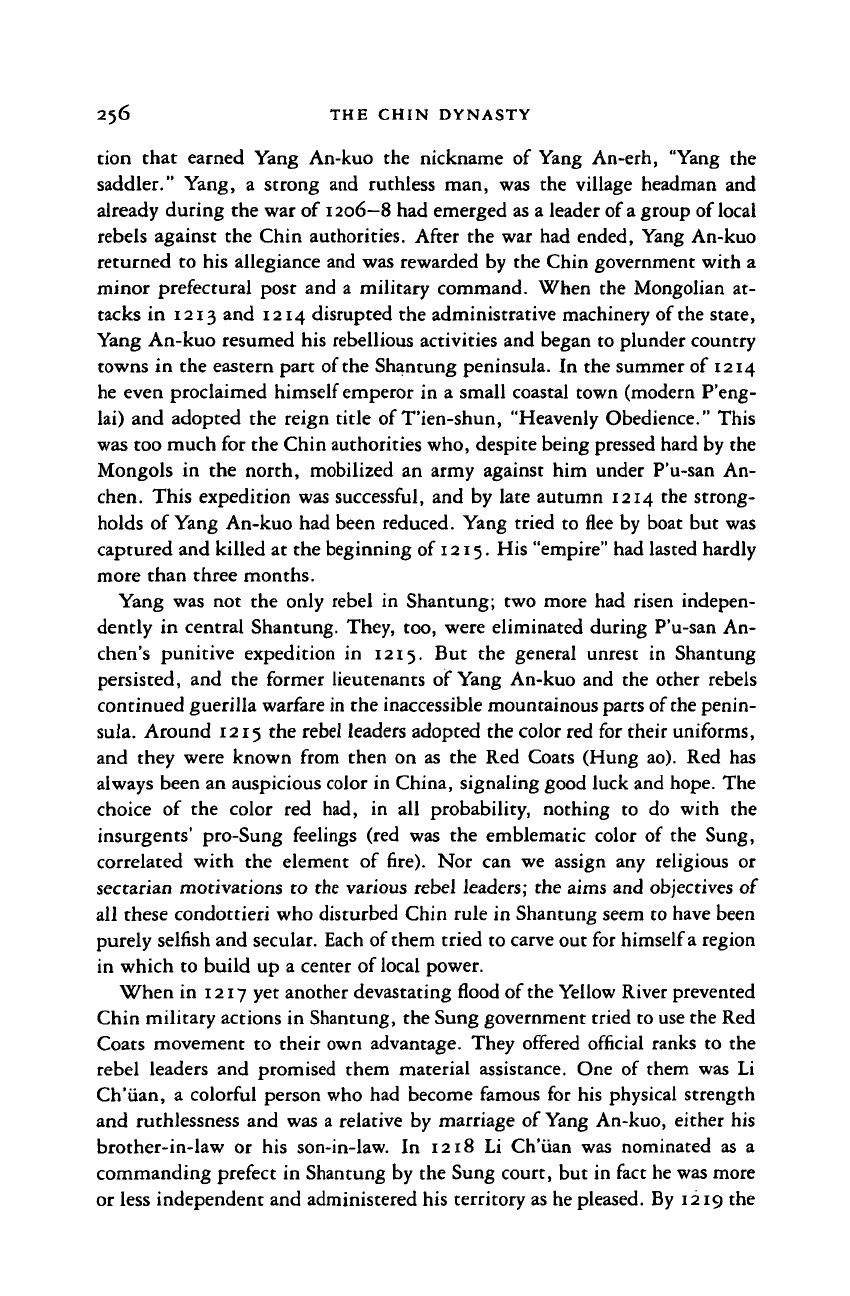

been a hotbed of social and religious unrest (see Map 20).

The first leading figure of

the

rebellion was Yang An-kuo. He came from a

fortified village in eastern Shantung inhabited by members of the Yang clan,

who specialized in manufacturing boots and other leather goods, an occupa-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ILIAO

|

Rebel regimes

Chin territory

1223

/

ITA-CHEN

WAN-NU PlbjHSIEN

1215-33

H

Oppressed

1233

by

Mongols preparatory

to invasion

of

KORYO

\

Vassal of Mongols

HS

I -

HSIA

conquered

by

Mongols

OCCUPIED

BY

MONGOLS

BY

1223

AIN

I NG

TERRITORY

LI-CHUAN

attacks Sung

1230

.killed

1231

500 km

300miles

MAP

20. The rebellions in Manchuria and Shantung

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

256 THE CHIN DYNASTY

tion that earned Yang An-kuo the nickname of Yang An-erh, "Yang the

saddler." Yang, a strong and ruthless man, was the village headman and

already during the war of 1206—8 had emerged as a leader of

a

group of local

rebels against the Chin authorities. After the war had ended, Yang An-kuo

returned to his allegiance and was rewarded by the Chin government with a

minor prefectural post and a military command. When the Mongolian at-

tacks in 1213 and 1214 disrupted the administrative machinery of the state,

Yang An-kuo resumed his rebellious activities and began to plunder country

towns in the eastern part of

the

Shantung peninsula. In the summer of 1214

he even proclaimed himself emperor in a small coastal town (modern P'eng-

lai) and adopted the reign title of Tien-shun, "Heavenly Obedience." This

was too much for the Chin authorities who, despite being pressed hard by the

Mongols in the north, mobilized an army against him under P'u-san An-

chen. This expedition was successful, and by late autumn 1214 the strong-

holds of Yang An-kuo had been reduced. Yang tried to flee by boat but was

captured and killed at the beginning of

1215.

His "empire" had lasted hardly

more than three months.

Yang was not the only rebel in Shantung; two more had risen indepen-

dently in central Shantung. They, too, were eliminated during P'u-san An-

chen's punitive expedition in 1215. But the general unrest in Shantung

persisted, and the former lieutenants of Yang An-kuo and the other rebels

continued guerilla warfare in the inaccessible mountainous parts of the penin-

sula. Around 1215 the rebel leaders adopted the color red for their uniforms,

and they were known from then on as the Red Coats (Hung ao). Red has

always been an auspicious color in China, signaling good luck and hope. The

choice of the color red had, in all probability, nothing to do with the

insurgents' pro-Sung feelings (red was the emblematic color of the Sung,

correlated with the element of fire). Nor can we assign any religious or

sectarian motivations to the various rebel leaders; the aims and objectives of

all these condottieri who disturbed Chin rule in Shantung seem to have been

purely selfish and secular. Each of them tried to carve out for himself a region

in which to build up a center of local power.

When in 1217 yet another devastating flood of

the

Yellow River prevented

Chin military actions in Shantung, the Sung government tried to use the Red

Coats movement to their own advantage. They offered official ranks to the

rebel leaders and promised them material assistance. One of them was Li

Ch'iian, a colorful person who had become famous for his physical strength

and ruthlessness and was a relative by marriage of Yang An-kuo, either his

brother-in-law or his son-in-law. In 1218 Li Ch'iian was nominated as a

commanding prefect in Shantung by the Sung court, but in fact he was more

or less independent and administered his territory as he pleased. By 1219 the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF CHIN AFTER II42 257

Chin government had lost its control over eastern Shantung where Li Ch'iian

reigned on his own. His submission to the Sung, which in any case had been

a formality, did not last long. From 1225, as the Mongolian armies advanced

into Shantung, Li Ch'iian realized that he would do well to come to terms

with the invaders. In 1227 he declared his allegiance to the Mongols and

later turned against his former protectors, the Sung. In 1230 he even ad-

vanced with his troops deep into Sung territory and attacked Yang-chou on

the Yangtze River. But this expedition failed, and Li Ch'iian was killed on 18

February 1231. His death marked the end of the Red Coats. In 1231 his

adopted son Li T'an (Marco Polo's "Liitan sangon") inherited his office and

continued the warlord career begun by his father. His loyalty turned out to

be as fickle as that of Li Ch'iian: When in 1262 he tried to surrender

Shantung to the Sung, Khubilai khan had him executed.

19

In later traditional Chinese historiography and in modern times the Red

Coats "movement" has frequently been labeled as nationalistic and patriotic

and as indicative of antiforeign feelings among the lower classes. The

Shantung insurgents were not, however, motivated by such modern concepts

as nationalism but, rather, were simple adventurers who tried to ally them-

selves with whichever major power could enhance their own prestige and

emoluments. In normal times none of them would have been able to resist

the Chin state for long, but in the turmoil following the Mongolian inva-

sions,

their rebellions could succeed to a limited extent and thus eliminate

Jurchen control over the eastern part of what remained of their state.

The

loss

of Manchuria:

Yeh-lii

Liu-ko and

P'u-hsien

Wan-nu

The Manchurian homelands of the Jurchens, where many of them still lived,

and, in particular, the comparatively prosperous region of Liao-tung, could

have been an area for retreat for the Chin government. Indeed, a Jurchen

minister had advised Hsiian-tsung to withdraw from the Central Capital

(Peking) to the Eastern Capital (Liao-yang) instead of K'ai-feng. However,

whereas the Liao-tung region was still under the firm control of Chin when

the Mongols attacked in 1211, northern and central Manchuria had already

been lost because of the insurrection of Yeh-lii Liu-ko. Liu-ko was a scion of

the Liao imperial family and, like so many other Khitan insurgents, had

cherished hopes of gaining independence from their Jurchen overlords. With

19 On the Red Coats movement under Yang An-kuo, see CS, 102, pp. 2243—5;

an

^ Franchise Aubin,

"The rebirth of Chinese rule in times of trouble: North China in the early thirteenth century," in

Foundations

and limits of state power in China, ed. Stuart R. Schram (London and Hong Kong, 1987),

pp.

113-46. On Li Ch'iian, see

T'o-T'o

et al., eds.,

Sung

shih (Peking, 1977), chaps. 476 and 477

(hereafter cited as SS); and his biography by Franchise Aubin in Sung

biographies,

ed. Herbert Franke

(Wiesbaden, 1976), vol. 2, pp. 542—6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

258 THE CHIN DYNASTY

his followers, mostly Khitan cavalry and soldiers, he declared his allegiance

to Chinggis khan in 1212, quickly gained control of central and northern

Manchuria, and was even allowed to adopt the title emperor of

Liao

in 1213.

A Chin punitive expedition against him in 1214 failed.

Liu-ko's puppet state survived until 1233 when the Mongols destroyed it.

The general responsible for the abortive Chin campaign against Yeh-lii Liu-ko

was Wan-nu, a member of

the

Jurchen P'u-hsien clan. After his defeat by the

Khitan rebels, Wan-nu retired with his troops to the region of the Eastern

Capital in southeastern Manchuria. Like so many others he realized that the

end of Chin was near and therefore tried to carve out a portion of territory for

himself from the remnants of the once-great empire.

In the spring of 1215 Wan-nu, too, declared himself independent, adopt-

ing the title of king and naming his state Ta-chen. This name was not a

geographical name, as practically all Chinese state names had been before this

(including that of Chin

itself,

though in this case there were overtones of

Chinese cosmological symbolism). Ta-chen is a highly literary expression

standing for "gold" in Taoist texts. This name, therefore, was meant to

proclaim that Wan-nu regarded himself as the true successor of

the

Chin, and

to underline this point he also adopted the clan name of

Wan-yen,

the ruling

house of Chin. The Taoist connotations of the state name and other features

of Wan-nu's regime were the result of the influence of

a

very curious person,

the Chinese Wang Kuei. He came from the region of modern Shen-yang and

had been a specialist in fortune-telling and the exegesis of

the

l-ching

(Book of

changes), at the same time being an adherent of the Taoist religion. Al-

though he lived as a hermit, Wang Kuei's reputation as a sage must have

been great because he had been summoned to the Chin court as long before as

1190.

He had refused and had again refused in 1215 when Hsiian-tsung had

invited him to court and offered him high office. Instead he became the chief

adviser of Wan-nu, whom he continued to serve until he was well over ninety

years old.

Wan-nu saw no chance of regaining the plains of central Manchuria, which

were at that time firmly held by Yeh-lii Liu-ko in alliance with the Mongols,

and so he turned eastward and to the north. His state covered the eastern,

forested, and mountainous part of Manchuria and also included the region of

the former Supreme Capital on the Sungari. Wan-nu's territories thus bor-

dered on Koryo, and he would certainly have liked to extend his domination

in that direction, but his invasions into Koryo led to no lasting results. The

state of Ta-chen existed for over eighteen years until the Mongols, during

their campaign against Koryo, advanced against Wan-nu's strongholds and

took him prisoner in 1233. Wan-nu's political role can be compared with

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE ANNIHILATION OF CHIN 259

that of the insurgent Li Ch'iian

in

Shantung: Both established themselves

in

border regions

far

away from the center

of

the Chin state,

and

both tried

to

remain independent

of

the advancing Mongols with whom, however, they

sometimes nominally allied themselves.

For the Chin state the loss

of

Manchuria, first

to

Liu-ko and Wan-nu and

subsequently

to

the Mongols, was a severe blow because

it

cut off the remains

of their state

in

China from their main horse-

and

cattle-breeding areas

and

from those regions with

a

substantial Jurchen population,

on

whose loyalty

they could have relied. As the situation was

in

1215, Chin had lost not only

the grain surplus—producing areas

of

northern Hopei

but

also

the

regions

from which they

had

obtained

a

great number

of

their cavalry horses.

It is

surprising that despite these formidable,

and

indeed fatal, losses, Chin

was

still able

to

survive

as a

state

for

some years.

One

reason was certainly that

from

1219

onward Chinggis khan directed

the

greater part

of his

forces

westward

in

order

to

attack western Asia; another factor may well have been

the fear

of the

Mongols that united loyal Jurchens

and

Chinese against

a

common foe.

THE ANNIHILATION

OF

CHIN, 1215-1234

The events

of

1215 had reduced the Chin territories

to

the region around

the

Yellow River

and

transformed

it

into

a

buffer state hemmed

in by the

Mongols,

Hsi

Hsia,

Li

Ch'iian

and his Red

Coats

in

Shantung,

and, of

course,

the

Sung

in the

south. Although

the

strategic situation seemed

hopeless,

the

Chin court

in

K'ai-feng decided

to

attempt

to

compensate

for

its losses

in the

north by means of

a

southern campaign against the Sung.

In

1217

it

decided

to

attack

the

Sung

on the

Huai River front,

but the

Chin

troops could

not

advance as deeply into Sung territory as they had been able

to do

in

1206-7.

At

the same time Hsi Hsia attacked the western borders of

Chin; here, however,

the

Chin were able

to

push back

the

invaders. There

followed a confused series of battles for border towns

in

the Huai region, with

no decisive results. Repeatedly

the

Chin sued

the

Sung

for

peace (which

always implied

the

demand

for

continued payments),

but in

1218 the Sung

did not even allow the Chin envoys

to

enter their territory. Another attempt

to invade Sung followed, this time with some tactical gains

but

no strategic

success.

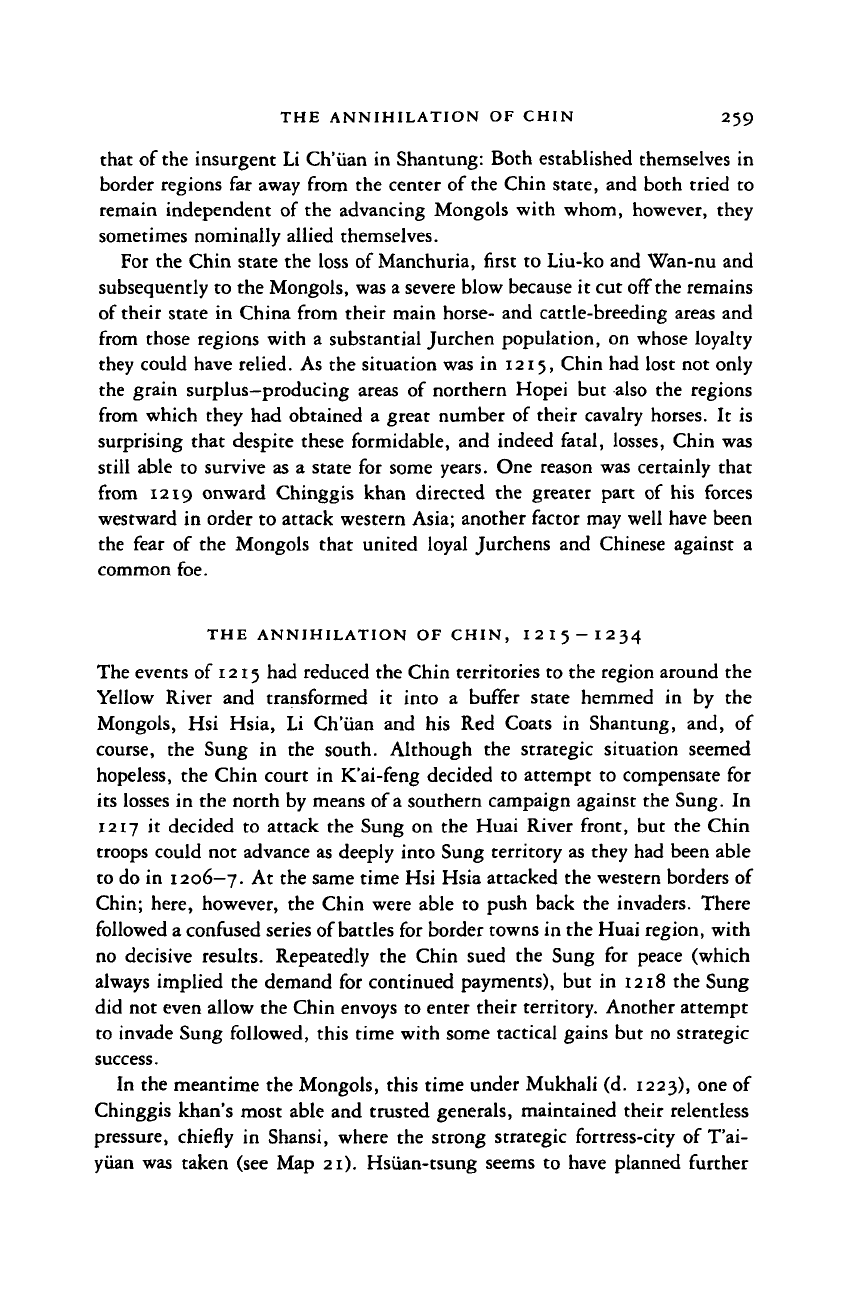

In the meantime the Mongols, this time under Mukhali (d. 1223), one of

Chinggis khan's most able

and

trusted generals, maintained their relentless

pressure, chiefly

in

Shansi, where

the

strong strategic fortress-city

of

T'ai-

yiian was taken

(see

Map 21). Hsiian-tsung seems

to

have planned further

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

'

Campaign in Shansi, 1218

1

Campaign in Shansi, 1219

Campaigns in Hopei and Shantung 1220

Campaigns in Shansi andShensi .•••"

1221-23 ;"

1221x

Feng-chou

Mongol

forces

fail

to take cities

300 km

~~2<Somiles

MAP

2

i.

Mukhali's campaigns against Chin

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008