The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE 271

risen

in

1207

to a

total of 47,000.

It

seems, therefore, that the Chin had

at

least as many officials as the Sung had in their early northern period (12,700 in

1046).

27

How, then, were these great numbers of officials recruited?

As the Liao had done before them, the Chin practiced

a

dualistic recruit-

ment policy. They established an examination system on Chinese lines, select-

ing candidates

on the

basis

of

merit.

At the

same time

the

selection

and

promotion

of

personnel was handled according

to

segregationist principles

based on the individual's group affiliation or personal position. Such institu-

tions as the operation

of

the principle

of

protection

(yin),

hereditary offices,

and

the

transfer

of

military personnel

to the

civilian bureaucracy played

a

major role

in

recruitment.

In

both examinations and the principle of favored

social groups the Chin state tried

to

find means

to

secure the preponderance

of Jurchen personnel.

At

the beginning

of

the dynasty, former Liao officials

were simply incorporated into the Chin administration when the Jurchens

invaded their territory, and the regularization

of

recruitment policy evolved

slowly.

The Chin examination system began

in

1123 when the first examinations

were held. From 1129 onward, triennial examinations

for

the chin-shih de-

gree were held; later they were held annually. Originally the examinations

given

in

the north differed from those given

in

the south (the newly incorpo-

rated Sung and Ch'i territories). The northern examination subjects concen-

trated on poetry and prose literature (which was regarded as easier); those

in

the south, on the Chinese classics. One reason for this regional differentiation

may have been the desire

to

make the examinations easier

for

the northern

Chinese, who,

as

former subjects

of

Liao, were perhaps regarded

as

more

reliable than

the

southerners. The examinations

on the

classics were abol-

ished for some time but then were revived and reorganized

in

1188—90.

In

addition

to the

Five Classics

(the

books

of

Changes, Rites, Songs,

and

Documents

and the

Spring

and

Autumn ~nnals),

the

texts used were

the

Analects

of

Confucius,

the

Meng-tzu,

the

Hsiao ching,

the

Yang-tzu (Yang

Hsiung's Fa-yen), and the Taoist classic

Tao-te

ching.

Although the positions with executive power, particularly

at

the highest

levels,

were mostly held by Jurchens, Chinese received an important means of

access

to the

bureaucracy through

the

chin-shih examinations. Over time,

more and more of the high-ranking Chinese were men who had attained their

ranks through their status as chin-shih graduates, rather than through other

means such as conferment of office

adpersonam

or military achievements. The

non-Chinese and non-Jurchen elements (Khitans, Hsi,

and

Po-hai)

did not

27 For the Sung figure, see Edward A. Kracke, Jr., Civil

service

in early

Sung

China, 960-1067, Harvard—

Yenching Institute Monograph Series no. 13 (Cambridge, Mass., 1953),

p.

55. The Chin figures

are

recorded

in

CS, 55,

p.

1216.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

272 THE CHIN DYNASTY

play a significant role in the examinations. Only five Po-hai and one Khitan

seem to have obtained the

chin-shib

degree during the whole history of Chin.

Emperor Shih-tsung must have realized that whatever its shortcomings,

the examination system provided the government with dependable servants.

He therefore opened a new career for Jurchens by establishing in 1173 a

Jurchen

chin-shih

degree (until this date there had been no degree require-

ment for Jurchen officials) and encouraged his countrymen to take the de-

gree.

The object of introducing a separate Jurchen degree may have been

twofold: It was in harmony with the general attitude of Shih-tsung, who

wished to preserve the Jurchen language and customs, and it was perhaps a

calculated measure to bring more Jurchen commoners into the bureaucracy in

place of the sometimes-overbearing and recalcitrant Jurchen aristocrats. But

unlike the Chinese, who eagerly seized the opportunities offered them

through the examinations,

the

Jurchens as a whole continued to advance their

careers without degree qualifications. Only 26 out of 208 high-ranking

Jurchen officials were

chin-sbih

degree holders. For them, their group privi-

leges and hereditary privileges remained the chief means of entering and

rising in the hierarchy.

The protection privilege (yin) was an important prerogative of those who

already held office and contributed to the self-perpetuation of

the

officials as a

class.

In the beginning and until the reign of Shih-tsung there was no

limitation on the number of family members whom the higher officials from

the seventh rank upward could nominate and "protect." Then

a

gradation was

introduced that fixed a maximum of six proteges for officials with the highest

(first) rank, proportionately fewer for those holding lower ranks, and that

denied the privilege altogether for those of the eighth rank and below. This

rule favored, of course, the high officials, the majority of whom were

Jurchens. Hereditary selection as practiced under the Chin had similar ef-

fects;

for example, Jurchens from the imperial Wan-yen clan had the privi-

lege of entering the palace service without formal protection. Jurchen com-

moners were also recruited for palace and palace guard service and from such

beginnings could make an official career. This is a clear parallel to the

Mongolian system of imperial guards

(kesig).

Also, the Jurchen

meng-an mou-k'o

system (see Chapter 4), with its hereditary offices, was a form of hereditary

selection based on group status.

Last, the practice of transferring meritorious military leaders to the civil

bureaucracy also favored the Jurchen elements of the population, as the

military organization remained very much

a

Jurchen preserve during most of

the dynasty. Discrimination was not confined to recruitment. After they had

joined the ranks of officialdom, the Chinese normally rose to higher ranks

more slowly than did their Jurchen counterparts. Promotion was formalized

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE 273

and based on both individual merit and seniority. Merits were calculated

according to a complex rating system, in an attempt to achieve objectivity.

The selection and promotion of personnel under the Chin dynasty there-

fore show many dualistic features. But we should emphasize that there was

no monopoly of office for the Jurchens, nor was there any general war on the

recruitment of Chinese. Rather, the Chin state aimed at a compromise and

tried to shape its institutions for recruitment in a way that could be used to

balance the influence of the different groups that made up its population.

The adoption of the civil service examinations for the Chinese, while at the

same time adding some checks and maintaining preferential methods of

promotion for the Jurchen, certainly helped bring about social stability. It

also is certain that examinations played a greater role in personnel selection

under the Chin than under the two other dynasties of conquest, Liao and

Yuan.

28

Military organization: meng-an mou-k'o and

border

administration

The meng-an mou-k'o system was a sociomilitary organization typical of the

Jurchens. It has been much studied, not only because of its inherent interest,

but also because it was in many respects a precursor of the Manchu banner

(niru) system that the Manchus used for establishing military control after

their conquest of China in the seventeenth century.

29

The Chinese syllables

meng-an mou-k'o are a transcription of two Jurchen words: Meng-an means

"thousand" and is a loan word from Mongolian

(mingghan;

Manchu: minggan).

Originally the leader of one thousand men in war was called a

meng-an;

later

the word also came to designate the unit under his command. Mou-k'o is

explained by the Chin shih as the leader of

one

hundred men. The word is not,

however, a numeral but is related to the Manchu word mukun, for which the

dictionaries give the meanings "clan, family, village, herd, tribe," and so on.

The meng-an mou-k'o system was based on the tribal divisions of the

Jurchens and was not a purely military organization but a comprehensive

social system into which in principle the entire Jurchen population was

organized under A-ku-ta. It soon became the most important military and

political means of control over the subjugated population. The basic unit was

the

mou-k'o.

The number of households attached to one unit varied. In theory

it should have been three hundred households but in reality was frequently

smaller. Nor did the meng-an have one thousand households, as the name

implies. Normally, a

meng-an

was composed of seven to ten mou-k'o.

28 For a detailed analysis of the Chin recruitment system, see Tao Jing-shen, "The influence of Jurchen

rule on Chinese political institutions," Journal of Asian

Studies,

30(1970), pp. 121—30.

29 On the

meng-an mou-k'o

system, see Mikami Tsugio, Kinshi kinkyu, vol. 1, pp. 109—417.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

274 THE CHIN DYNASTY

The

mou-k'o

itself was subdivided into

p'u-li-yen

(there also are several other

transcriptions of this word), a word probably related to Manchu

feniyen,

"flock, herd."

P'u-li-yen,

like the other words, designated both the unit and

the title of its leader. The

p'u-li-yen

had fifty households under his command.

All able-bodied males in a household had to serve as soldiers. Male household

servants were also conscripted and served as auxiliary soldiers

(a-li-bsi;

cf.

Manchu ilhi, "subordinate, assistant"). Each fully equipped soldier was enti-

tled to be accompanied by an auxiliary soldier during

a

campaign. The

mou-k'o

in the Manchurian homelands of the Jurchens settled in and around stock-

aded villages, and most bore the name of their original geographic location,

which they usually retained even after they had been transferred to other

parts of the state.

The formal introduction of this system is said to have taken place under

A-ku-ta in 1114, but it certainly goes back to much earlier times. It under-

went many changes in the following years. When

the

Jurchens conquered the

Liao state, they used the

meng-an mou-k'o

system to organize those Khitan,

Hsi,

Chinese, and Po-hai who had surrendered. Hereditary office in the

system was a considerable inducement for Khitan leaders to join the Jurchens

with their subordinates.

The number of households in a Khitan

mou-k'o

unit was, however, smaller

than among the Jurchens and amounted only to 130. We do not know how

many households were normally attached to a Po-hai or a Chinese

mou-k'o.

In

one case at least, a Chinese

mou-k'o

consisted of only 65 households.

30

The

formation of new Chinese units came to a stop in 1124, but the number of

Chinese serving in the Chin army must already have been quite considerable,

for during the campaign against Sung in 1126—7, several Chinese divisions

each of ten thousand men fought against their countrymen under Jurchen

command. It is not quite clear how many of these were simply conscripts

drafted for the campaign and how many were part of regular Chinese

meng-an

mou-k'o

units. The number of soldiers outside the

meng-an mou-k'o

system

usually varied according to the needs of the military situation. They were

conscripted from the civilian population when an emergency arose and were

disbanded when the campaign had come to an end. During the last years of

the dynasty, when the

meng-an mou-k'o

system had seriously declined, the

Chinese population, including even high officials and dignitaries, were sub-

jected to ruthless conscription for military service.

Hereditary office for Chinese and Po-hai unit commanders was abolished

in 1145 but was retained for the Khitan and Hsi units. At the same time, the

existing

meng-an mou-k'o

were graded into three classes. The first-class units

30 CS, 44, p. 993.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE 275

were those commanded

by

imperial clan members; second-class units were

commanded

by

other Jurchen; and third-class units were those composed of

Khitans, Hsi, Chinese, and Po-hai. This attempt

to

give different status

to

units

of

different origin was, however, abolished under Hai-ling wang

in

1150.

This ruler, who,

as we

have seen, tried

to

curb

the

power

of the

Jurchen aristocracy, also ordered the transfer

of

those units still commanded

by imperial clan members from the Supreme Capital

to

other towns

in the

southern parts of the state. The whole system suffered a severe blow when the

mobilization against Sung was resisted by some Khitan and Hsi units. These

were mostly stationed

on

the northwestern borders and had good reason

to

fear for the safety

of

their dependents

if

all their warriors were mobilized for

the campaign, because Mongolian raids were

a

constant menace

in

the area.

They rebelled

in

1161. After the rebellion was crushed, many of their units

were disbanded,

and the

households were distributed among the Jurchen

units.

Only those who had remained loyal were retained and accorded

the

privilege of hereditary office as before.

Another factor impairing the efficiency of the entire system was economic.

As the meng-an mou-k'o units were also administrative and economic units

—

similar perhaps

to

the military colonies under Chinese dynasties

—

they had

been assigned land for agriculture and were supposed to be economically

self-

sufficient. Many Jurchens had only limited experience

of

farming and were

unaccustomed

to

farming

in a

Chinese environment. Some

of

them hired

Chinese

to

work on their land, and they themselves led an idle life, drinking

excessively and neglecting their military skills. Some units were also given

government land of poor quality. Unable

to

compete with the more skillful

Chinese

and

exploited

by

usurious moneylenders,

a

great number

of the

Jurchen commoners

in the

units were reduced

to

poverty. They were

ex-

ploited not only by Chinese but also by their own richer and more powerful

countrymen, particularly by members of the imperial clan who had managed

to acquire huge land hold ings

at the

expense

of

the less fortunate Jurchens

and, of course, the Chinese.

In sharp contrast with earlier times, when the meng-an mou-k'o warriors,

chieftain and commoner alike, lived together like "fathers, sons and broth-

ers"*

1

and

when

a

frugal way

of

life was normal,

a

deep gulf now arose

between the rich and poor Jurchens. Emperor Shih-tsung showed great con-

cern for the deteriorating conditions of his impoverished countrymen. Relief

measures were undertaken; government grain was distributed

to

impover-

ished units; and agricultural techniques were promoted. Sumptuary regula-

tions and laws against luxury were enacted

to

inhibit drinking and extrava-

31 Ta Chin kuo chih, 36,

p.

278.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

276 THE CHIN DYNASTY

gance, and orders for regular military exercises were given. Military colonists

were moved from poor lands to better regions and there was an attempt to

concentrate those Jurchens living scattered among the Chinese into more

closed and compact groups.

A general census of the whole

men-an mou-k'o

population was taken in

1183,

in which not only the people but also their lands, cattle, and slaves

were registered. The results showed such a gross disparity between rich and

poor that Shih-tsung's government resorted to a redistribution of lands and

confiscation of

excessive

landholdings. These measures temporarily improved

the situation. To social historians, the census figures are of interest. Apart

from the imperial clan, whose holdings were registered separately, the whole

meng-an mou-k'o

population was 6,158,636 persons living in 615,624 house-

holds.

Of these persons, 4,812,669 were commoners (the majority of them

Jurchen), and the rest were slaves attached to individual households. The

number of

meng-an

was 202, that of

mou-k'o

1,878.3* Under Shih-tsung's

successors, the system apparently lost its effectiveness, and when the Mon-

gols invaded, the Chin government had to rely more and more on conscripted

troops. But up to the end the

meng-an mou-k'o

remained the basic organiza-

tion of the Jurchen military machine.

The emperor and the crown prince had their own

mou-k'o.

This imperial

guard was called

ho-cha mou-k'o {ho-cha

is the transcription of

a

Jurchen word

perhaps related to Manchu

hasban,

"protection, screen"). The members of

this regiment, numbering several thousand men, were recruited from among

the normal units. Candidates had to be

five

feet, five inches tall and to pass a

military test. Within the regiment there was a small elite unit, that of the

"close attendants," numbering two hundred warriors. They alone had the

privilege of bearing arms in the presence of

the

emperor. The members of this

personal bodyguard had to be at least five feet, six inches tall.

The higher command structure of the Chin armies was relatively simple.

Several

meng-an

mou-k'o formed a wan-hu, literally "ten thousand house-

holds."

The next-highest office was that of the chief commander

(tu-t'ung).

The commander in chief(/»

yiian-shuai)

acted as generalissimo, but this office

was activated only in times of war. In many respects the higher military

hierarchy of the Chin was modeled on that of their Liao predecessors. This is

also true for the tribal units that had existed under the Liao and that had been

taken over by the Chin, sometimes without even changing their names.

These units were mostly stationed on the northwestern borders and consisted

of Khitans, Hsi, or members of other tribes. Unlike the agricultural

meng-an

32 For an analysis of the demographic aspects of the

rafng-rf/Jmoa-i'o

system, see Ping-ti Ho, "An estimate

of the total population of Sung—Chin China," in ttutits

Song

in mmoriam ttitnne Baldzs, ed. Francoise

Aubin, series i, no. I (Paris, 1970), pp. 33—45.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOCIAL STRUCTURE 277

mou-k'o

of the Jurchens proper, these tribal groups were nomad cattle breed-

ers,

a fact that is, for example, reflected in the title commissioner of herds

{ch'tin-mu

shih) for some of these units. But like the Jurchen units they were

both military units and self-sufficient socioeconomic communities. Under

the Chin, there were altogether twelve of these commissioners of

herds.

Some

of them had under their command former members of the imperial camp

guards (ordo) of the Liao and their descendants, but there was also one

commissioner commanding Jurchen tribesmen. It seems that these commis-

sioners were organized formally at a rather late date, under Emperors Shih-

tsung and Chang-tsung, in connection with the preparations for defense

against the Mongols.

Another feature inherited from the Liao were the chiu units. These were

originally detachments of frontier soldiers. Under the Chin there were nine

chiu units, mostly stationed in northeastern Manchuria. Finally, there were

eight special offices named tribal commanding prefects

{tsu-pu

chieh-tu shih),

whose names suggest the partly Tangut, Mongolian, Khitan, and Hsi affilia-

tions of their subordinate populations. They were stationed along the western

and northwestern borders of the state and, like the other organizations, were

military organizations for border defense.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

It is strangely ironical that the Chin shih, although the official history of a

"semibarbarian" state, has preserved much clearer information about the

system of population control and census taking than most of the other

Chinese dynastic histories have.

33

Even for the Sung we have, despite a

wealth of specific data, no very clear picture of the definition of age groups

and similar registration policies. From the relevant chapter in the Chin shih

we have, however, unambiguous information about not only the age groups

but also the methods by which the population was enumerated every three

years.

The population registers were based on enumerations made at the

lowest level, that is, by village headmen and, for the

meng-an mou-k'o

popula-

tion, by the stockade overseers. The number of headmen per village varied

with the number of households; those with fewer than fifty households had

only one headman, whereas larger villages with three hundred or more

households had four. In the towns and cities the corresponding overseers were

in charge of urban wards or quarters. At the beginning of a census year, these

local overseers had to visit all households and list the names, ages, and sex of

the family members. The figures obtained were added together and then sent

33 This point is stressed by Ho Ping-ti in ibid.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

278 THE CHIN DYNASTY

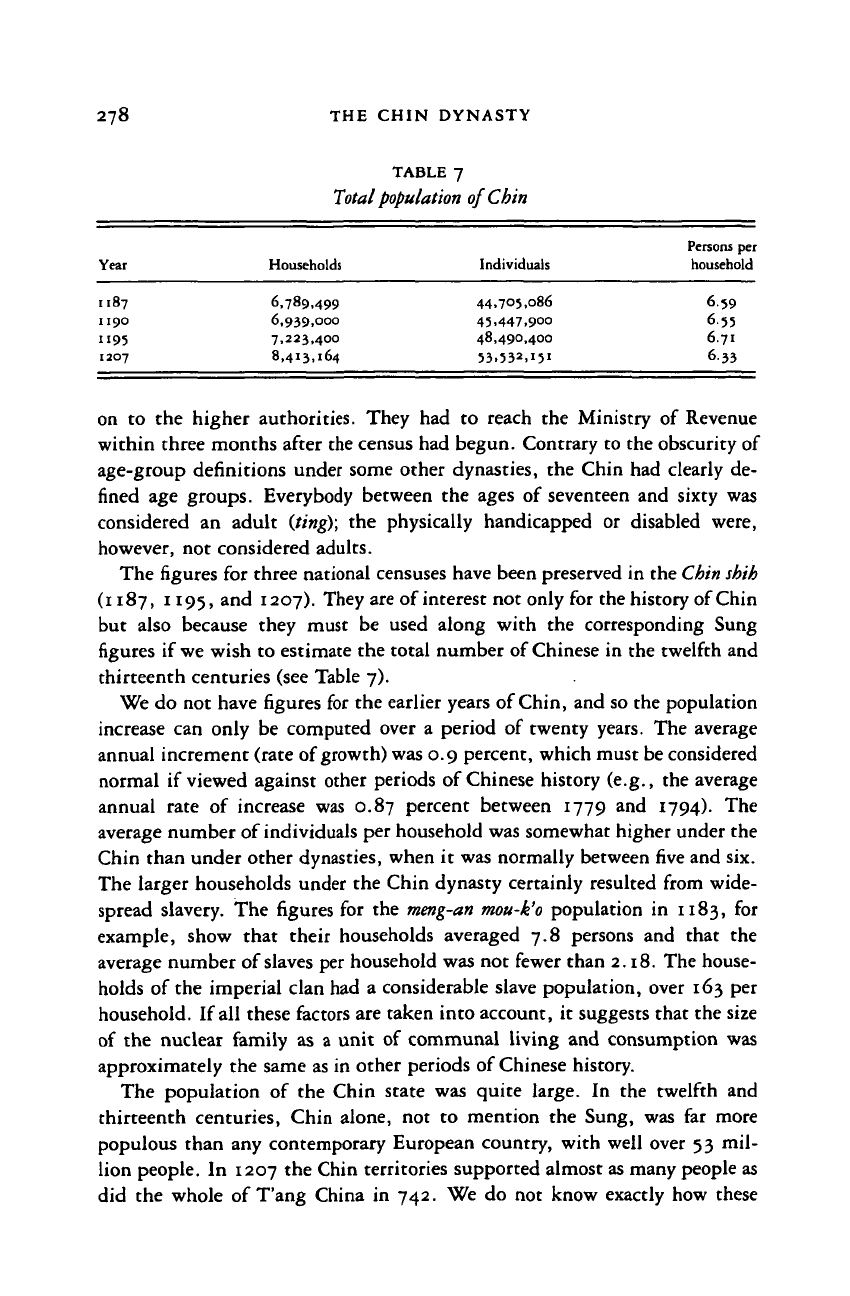

Year

1187

1190

1195

1207

TABLE

7

Total population

Households

6,789,499

6,939,ooo

7,223,400

8,413,164

of Chin

Individuals

44,705,086

45.447.900

48,490,400

53.532,15'

Persons

per

household

6.59

6.55

6.71

6.33

on

to the

higher authorities. They

had to

reach

the

Ministry

of

Revenue

within three months after the census had begun. Contrary

to

the obscurity of

age-group definitions under some other dynasties,

the

Chin

had

clearly

de-

fined age groups. Everybody between

the

ages

of

seventeen

and

sixty

was

considered

an

adult (ting);

the

physically handicapped

or

disabled were,

however,

not

considered adults.

The figures

for

three national censuses have been preserved

in

the

Chin shih

(1187,

1195,

and

1207). They are

of

interest not only

for

the history of Chin

but also because they must

be

used along with

the

corresponding Sung

figures if

we

wish

to

estimate the total number of Chinese

in

the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries (see Table

7).

We do

not

have

figures

for

the earlier years of Chin, and so the population

increase

can

only

be

computed over

a

period

of

twenty years.

The

average

annual increment (rate of growth) was 0.9 percent, which must be considered

normal

if

viewed against other periods

of

Chinese history (e.g., the average

annual rate

of

increase

was 0.87

percent between

1779 and

1794).

The

average number of individuals per household was somewhat higher under the

Chin than under other dynasties, when

it

was normally between

five

and six.

The larger households under

the

Chin dynasty certainly resulted from wide-

spread slavery.

The

figures

for the

meng-an mou-k'o

population

in

1183,

for

example, show that their households averaged

7.8

persons

and

that

the

average number of

slaves

per household was

not

fewer than 2.18. The house-

holds

of

the imperial clan had

a

considerable slave population, over 163

per

household.

If

all

these factors are taken into account,

it

suggests that the size

of

the

nuclear family

as a

unit

of

communal living

and

consumption

was

approximately

the

same as

in

other periods of Chinese history.

The population

of the

Chin state

was

quite large.

In the

twelfth

and

thirteenth centuries, Chin alone,

not to

mention

the

Sung,

was far

more

populous than

any

contemporary European country, with well over

53 mil-

lion people.

In

1207 the Chin territories supported almost as many people as

did

the

whole

of

Tang China

in

742.

We do not

know exactly how these

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHNIC GROUPS 279

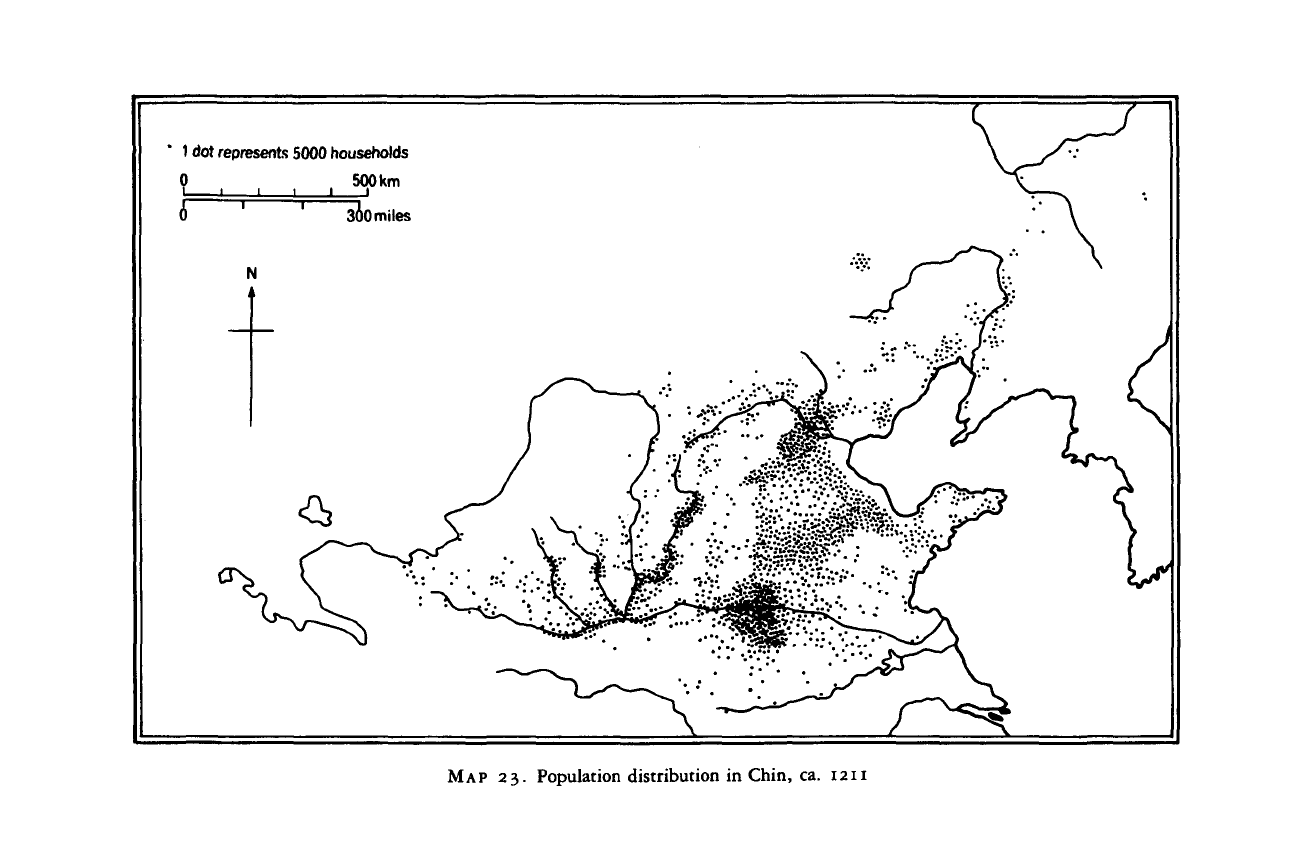

many millions were distributed geographically, but the geographical mono-

graph of the Chin shih gives the number of households for each prefecture.

Unfortunately, this source does not say to which year these figures refer, but

it may be assumed that it was shortly before the Mongolian conquests and the

loss of Manchuria to P'u-hsien Wan-nu in 1215, because the total number of

households is even larger than that of the 1207 census. The geographical

distribution of the population over the area of the Chin empire is shown on

Map 23.

This distribution shows that almost a quarter of the entire Chin population

lived in the Yellow River plains around K'ai-feng (modern Honan). Another

region of great population density was eastern Shantung. The third most

heavily peopled area was Peking and its surroundings. It also is clear that the

Manchurian homelands of the Jurchens were only sparsely populated, although

these low figures might be partly due to difficult communications and corre-

sponding deficiencies in census taking in these remote districts. It is also

remarkable how few people lived in the strategic area bordering on the Hsi

Hsia state in present-day Kansu. By far the biggest city in the whole Chin

empire was the Southern Capital, K'ai-feng, with

1,746,210

households in

the metropolitan district. The second largest city was the Central Capital

(Peking), with 225,592 households, whereas the old Supreme Capital (Hui-

ning) in Manchuria contained only 31,270 households. The Eastern Capital

(Liao-yang) was only slightly larger, with 40,604 households.

ETHNIC GROUPS

Although we can get a rather clear picture of the distribution of the Chin

population, at least for one single year, we know far less about the relative

strength of

the

ethnic groups within the Chin state. No statistics show us the

precise percentage of these groups even locally. The figures given for the

meng-an mou-k'o

population cannot be used for this purpose because these

military units included not only the Jurchens but also other ethnic groups.

Only

a

very rough estimate is possible. If

in

1183 there were over 4.8 million

free military colonists, it might perhaps be assumed that the greater major-

ity, say 80 percent of them, were indeed Jurchens and the rest Khitans, Po-

hai,

or Chinese, so that the Jurchen population must have been something

like 4 million, considerably less than 10 percent of the total.

Not all Jurchens could consider themselves superior to other ethnic

groups. Those living in the military colonies were segregated from the

surrounding Chinese population, and the privileges for Jurchens were most

strongly felt in the bureaucracy, in which Jurchens not only occupied most of

the important positions but also enjoyed speedier promotion than others did.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1

dot represents 5000 households

MAP

23. Population distribution in Chin, ca. 1211

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008