The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A-PAO-CHI BECOMES THE NEW KHAGHAN 6l

the Wu-ku (tentatively identified with the Onggirad). Liao dominion was

steadily spreading north and northwestward.

Meanwhile, relations with the Chinese border areas remained strained. In

Lu-lung, the governor, Liu Jen-kung, was deposed in 907 by his son Liu

Shou-kuang, who continued his father's hostility toward the Khitan. In 909

a Khitan army led by a member of the Hsiao consort family drove deep into

Hopei and defeated Liu Shou-kuang somewhere southwest of present-day

Tientsin. But Liu's ambitions were set high; in 911 he proclaimed himself

emperor of the independent state of

Yen

(once the name of An Lu-shan's rebel

regime) and began to invade the neighboring provinces to enlarge his terri-

tory. But on the same day that he proclaimed himself emperor, the Khitan

occupied P'ing-chou, west of Shan-hai kuan. In 912 A-pao-chi personally led

an army to attack Liu Shou-kuang. Then in the next year Li Ts'un-hsii - who

had been the Sha-t'o ruler of Ho-tung since the death in 908 of his father Li

K'o-yung and who later became Emperor Chuang-tsung of the Later Tang

(reigned 923—6)

—

was alarmed by Liu Shou-kuang's aggressive actions, de-

cided to intervene, invaded Lu-lung, and took its capital, Yu-chou. Liu

Shou-kuang was captured and the Yen regime was destroyed; Lu-lung was

incorporated into the Sha-t'o domain, known to its contemporaries as Chin.

Li Ts'un-hsii now ruled effectively over the entire border region fronting

Khitan territory and was steadily consolidating a powerful regime that pre-

sented a major challenge to the Liang dynasty based in Ho-nan that had been

set up by his father's old rival Chu Wen in 907.

A-pao-chi had, of course, once sworn brotherhood with Li K'o-yung, but

the latter had never forgiven him for subsequently trying to establish friendly

relations with his hated enemy Chu Wen, emperor of the Liang. Li Ts'un-

hsii,

in control of the powerful satrapy of Chin, which now encompassed

northern Ho-pei as well as Ho-tung, was a far more powerful and threatening

adversary for the Khitan than Liu Shou-kuang had been. Fortunately for A-

pao-chi, Li Ts'un-hsii was preoccupied with more important ambitions con-

cerning China. For the time being, therefore, an uneasy truce prevailed on

the Khitan frontier.

Relations with his neighbors were also of secondary importance to A-pao-

chi,

for he faced a major problem in maintaining his supreme power among

the Khitan. After his election as leader in 907, his plans to consolidate his

absolute authority did not go unchallenged. The biggest threat came from

his younger brothers and other members of the Yeh-lii clan, who had become

the new Khitan aristocracy following the eclipse of the Yao-lien. In tradi-

tional Khitan society, succession to both the khaghanate and tribal

chief-

tainships had commonly passed to brothers or cousins. Moreover, custom

demanded that the ruler be reelected every three years, when another mem-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

62 THE LIAO

ber of the tribal council or another candidate from his own clan might be

chosen to replace him. In 910, when his reelection was due, A-pao-chi failed

to go through this procedure, and his brothers, feeling cheated of their own

chances of succession, sought to prevent him from establishing a permanent

dynasty based on succession from father to son, as this would have ended

forever their own claims to leadership. Most resentful was the eldest of A-

pao-chi's younger brothers, La-ko.

In 911 four of the younger brothers rebelled, and in 912 another plot to

assassinate A-pao-chi engineered by the same four brothers was uncovered

before it could be carried out. In 913, when A-pao-chi's second three-year

term as khaghan came to an end and he again refused to put himself forward

for reelection, a far more serious rebellion, led by his brothers, his uncle, and

his cousin who was chieftain of the I-la, broke out and was suppressed with

much bloodshed. All these rebellions failed, however, and their defeat acceler-

ated the accumulation of power in A-pao-chi's hands. But he was not yet a

complete despot. He remained sufficiently enmeshed in the Khitan tribal

system that he could not simply eliminate all his rivals. His brothers' lives

were spared, although his uncle and cousin and more than three hundred of

their supporters were executed.

To compensate the brothers and other collateral relatives and to prevent

further unrest among the Yeh-lii clan, A-pao-chi combined their families

into the so-called Three Patriarchal Households

(san-fu

fang),

encompassing

all the descendants of A-pao-chi's grandfather, which became one of the

privileged lineage groups of the Liao empire (see Figure 1). But the dissatis-

faction over a permanent hereditary leadership among the imperial family

and the struggles over the succession did not cease there. In 917 La-ko again

rebelled and fled to Yu-chou where he was received by Li Ts'un-hsii, ruler of

the Chin, who appointed him a prefect. Later, when Li Ts'un-hsii became

emperor of the Later T'ang in 923, he executed La-ko as a gesture of goodwill

and friendship toward A-pao-chi. In 918 there was another short-lived upris-

ing led by another of the brothers, Tieh-la. Disputes over the leadership and

succession troubles frequently flared up among A-pao-chi's descendants.

In 916, when he should yet again have presented himself to the tribal

leaders for reelection, A-pao-chi took still more drastic steps to consolidate

his authority on a permanent basis. First he went through a Chinese-style

accession ceremony, claiming for himself the title of emperor of the Khitan

and adopting a reign title,

1

' thus proclaiming his independence of the Liang

15 There is great confusion about T'ai-tsu's reign titles Shen-ts'e (916) and T'ien-tsan (922), which some

scholars claim were invented later. The first reign title for which there is independent contemporary

confirmation is that of T'ien-hsien, adopted by A-pao-chi in the last year of his life (926) and also used

under his successor T'ai-tsung. See Arthur C. Moule, The

rulers

of China (London, 1937), pp. 91 fT.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

A-PAO-CHI BECOMES THE NEW KHAGHAN 63

(whose calendar the Khitan had previously used) and signifying that he was

now the equal of the Chinese rulers. Perhaps most significant of all, he

proclaimed his eldest son Pei (900-37; Khitan name, T'u-yii) as heir appar-

ent. This formally ended the claims of his brothers and other clan members

to the succession and also preempted the rights of the tribal elders to elect

their leader in the traditional way. Pei himself was much influenced by

Chinese culture and most unlikely to revert to the old Khitan custom. Yet

another symbolic gesture toward the founding of

a

Chinese-style regime was

the establishment of the first Confucian temple, which must have seemed

very out of

place

among these bloodthirsty and violent warriors, even though

a small minority of Khitan nobles were beginning to become versed in

Chinese letters.

In 918, in another step toward establishing a more permanent regime, A-

pao-chi ordered the building of a great capital city, the Imperial Capital

(Huang-tu), later to be known as the Supreme Capital (Shang-ching). This

was constructed at Lin-huang, north of the Shira muren (a place that later

became the Mongol city of Boro Khoton), in the ancient central territory of

the Khitan tribes. For its construction, mass levies of corvee labor were

mobilized, during the busiest months of the agricultural year: A-pao-chi had

not yet grasped the finer points of Chinese-style governance of an agrarian

population. The work is said to have been finished in one hundred days, but

in fact it continued for some time. Later in the same year he ordered the

construction of Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist temples at the capital. In

the last year of A-pao-chi's life the capital was further extended, and a series

of halls and ancestral shrines were built. Eventually the capital covered an

area of 27 It: It was built on a standard Chinese plan with walls, gates, a

street grid, palaces, ministry buildings, temples, courier stations, and so

forth. It was in fact a dual city, for to the south was a separate Chinese city,

with dense housing and markets. It also had a special quarter for the Uighur

merchants, who played a major part in the trade of the north, and lodgings

for envoys from foreign nations. We cannot accurately date the growth of the

city, as parts of the walls were rebuilt in 931, and further construction went

on well into the eleventh century. By then it was only one of five capital

cities.

The construction of a permanent capital symbolized A-pao-chi's rapid

development of a centralized administration and institutions. Already by this

time A-pao-chi seems to have begun the dualistic form of administration that

continued until the end of the

Liao,

with

a

Northern Administration responsi-

ble for the tribal portion of his domain and a Southern Administration,

organized more closely on the T'ang model, responsible for the sedentary

portion and especially the Chinese population. As early as 910, A-pao-chi

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

64 THE LIAO

appointed his brother-in-law Hsiao Ti-lu to head his Northern Administra-

tion. This development culminated in the formal division of the empire in

947 into Northern and Southern divisions (Pei-yiian, Nan-yiian), but the

process was clearly under way long before this. In the later years of A-pao-

chi's reign, captured Chinese officials played a major role in developing the

administrative system. Han Yen-hui (d. 959), a former provincial finance

official from Lu-lung, devised a tax system and was largely responsible for

designing the Chinese administration of the south.'

6

Dating the development of changes in governmental organization in this

early period is impossible. Probably much remained personal and informal.

The existence of a fixed capital should not be taken to imply a permanent

government structure with regular premises and a fixed court, as under a

normal Chinese dynasty. Instead, government remained with the emperor's

entourage, and the court was peripatetic, annually progressing on a circuit of

seasonal hunting grounds

(na-po)

and, from time to time, accompanying the

emperor on his frequent campaigns.

17

The "court" was a great portable city of

tents and pavilions, transported on a train of ox-drawn wagons. The entour-

age lived partly off the land surrounding their camp: The local inhabitants

were sometimes granted tax exemptions in recompense. In the early days at

least, the imperial palace at the capital was not the expected vast range of

lavish buildings but, rather, the site where the emperor's tents were pitched

when he was in residence.

In 916 and 917 A-pao-chi once again attempted to intervene in China.

At this time Li Ts'un-hsii and the Liang emperor Mo-ti (Chu Yu-chen) were

locked in conflict, righting for control of central and southern Hopei.

A-pao-chi seized the opportunity to invade Li Ts'un-hsii's territory in north-

ern Ho-tung and Hopei. In 917 the Khitan besieged Yu-chou for two

hundred days and were finally driven off only by the arrival of a powerful

army from Ho-tung led by Li Ssu-yiian, later to become the second em-

peror, Ming-tsung, of the Later T'ang. In 921 and 922 the Khitan again

invaded Hopei, this time at the request of

a

local governor nominally allied

to Li Ts'un-hsii and the Sha-t'o leaders in Ho-tung. They easily overran the

main frontier passes, gained control of some Chinese territory east of mod-

ern Shan-hai-kuan (then known as Yii-kuan), and penetrated as far south as

Chen-chou. Li Ts'un-hsii personally mobilized an army to repel them on

this occasion.

16 LS, 74, p. 1331—2.

17 On the na-po, see Yao Ts'ung-wu, "Shuo Ch'i-tan te na po wen hua," in vol. 2 of his

Tung-pet

sbib lun

is'ung (Taipei, 1959), pp. 1—320. See also the classic study by Fu Le-huan, dating from 1942,

included in revised form in his

Liao

shib

Is'ung

k'ao (Peking, 1984), pp. 36—172.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

A-PAO-CHI BECOMES THE NEW KHAGHAN

9

, , , ,

'•

0

' ' 3

00

km

DOmiles

isi

CH'IEN

SHU

/liiiiliit

\NAIU

•

Ch'eng-tu

^—-~<\0

J

^^

"

Khitan

%&$&$&&&*&•

SOUTHERN

TUNG-TAN

CAPITAL^

formerly PO-HA

mdr

1111%

jljll

illll

i|xj*Ch'u-qhou •••..•••

MAP

2

.

The Khitan and north China, A.D. 924

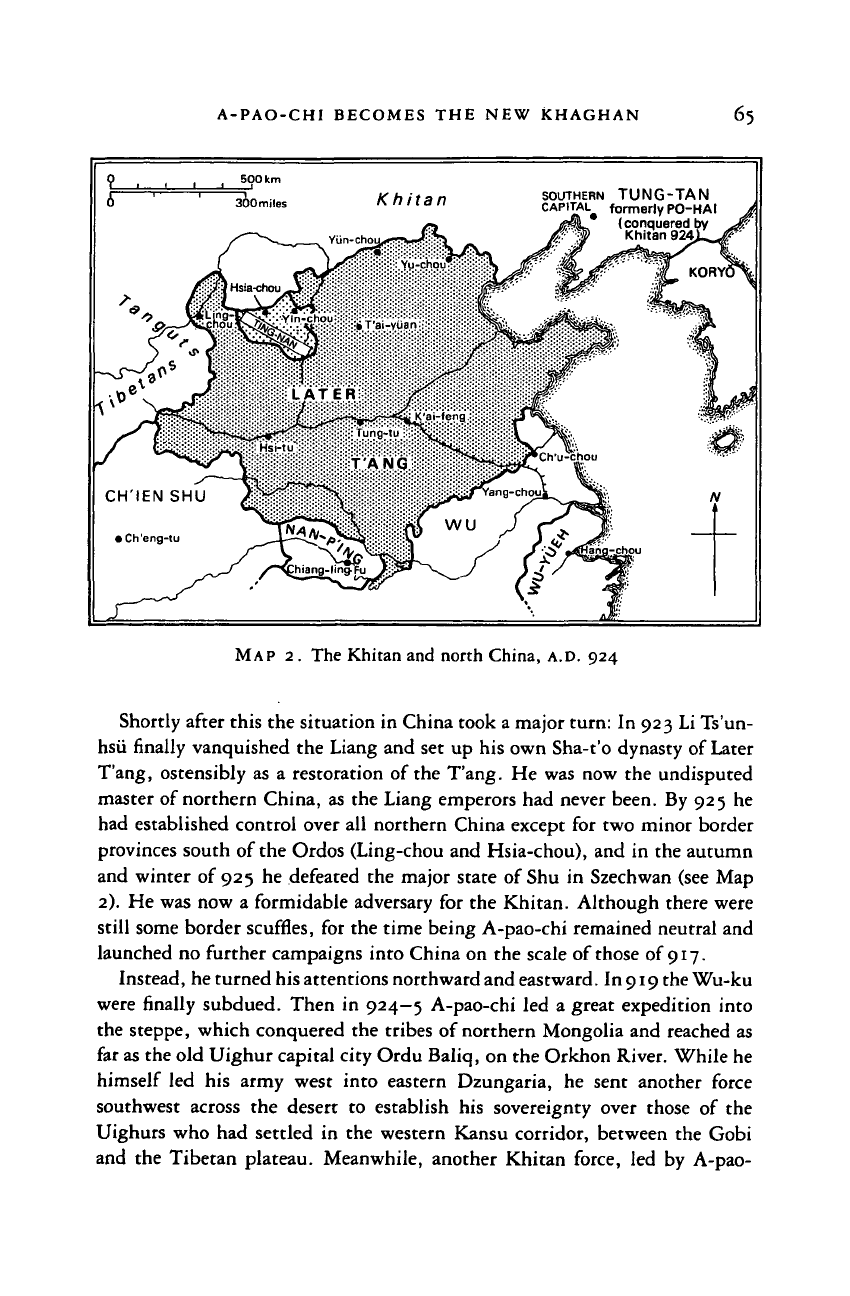

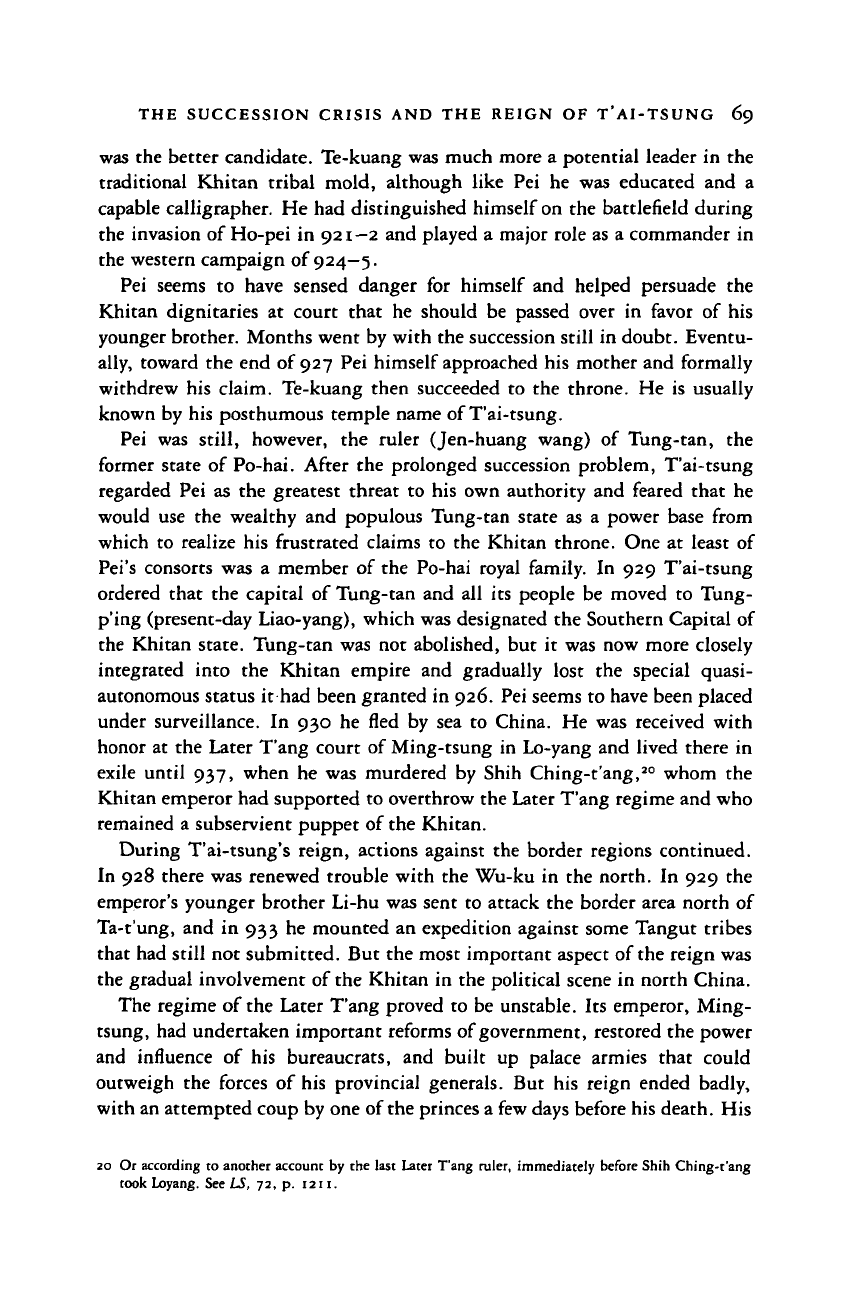

Shortly after this the situation in China took a major turn: In 923 Li Ts'un-

hsii finally vanquished the Liang and set up his own Sha-t'o dynasty of Later

T'ang, ostensibly as a restoration of the T'ang. He was now the undisputed

master of northern China, as the Liang emperors had never been. By 925 he

had established control over all northern China except for two minor border

provinces south of the Ordos (Ling-chou and Hsia-chou), and in the autumn

and winter of 925 he defeated the major state of Shu in Szechwan (see Map

2).

He was now a formidable adversary for the Khitan. Although there were

still some border scuffles, for the time being A-pao-chi remained neutral and

launched no further campaigns into China on the scale of those of 917.

Instead, he turned

his

attentions northward and eastward. In 919

the

Wu-ku

were finally subdued. Then in 924-5 A-pao-chi led a great expedition into

the steppe, which conquered the tribes of northern Mongolia and reached as

far

as

the old Uighur capital city Ordu Baliq, on the Orkhon River. While he

himself led his army west into eastern Dzungaria, he sent another force

southwest across the desert to establish his sovereignty over those of the

Uighurs who had settled in the western Kansu corridor, between the Gobi

and the Tibetan plateau. Meanwhile, another Khitan force, led by A-pao-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

66 THE LIAO

chi's second son Te-kuang (Khitan name Te-chin, later to become the Liao

emperor T'ai-tsung; reigned 927—47), crossed the Gobi southward and estab-

lished Khitan control over the tribal peoples of the Yin-shan area and the

northeastern corner of the Ordos, including remnants of the T'u-yii-hun and

some minor Tangut groups.

In 926, only a year after returning home from these extensive conquests,

A-pao-chi set out on a still more ambitious expedition. The target this time

was the powerful state of Po-hai (Parhae), which ruled over a large area of

eastern Manchuria and the coastal region beyond and with which there had

been border clashes in 924. Po-hai, unlike A-pao-chi's other adversaries, was

not a tribal federation of nomadic pastoral peoples but a centralized state on

the Chinese model that had long enjoyed stable relations not only with China

but also with Korea and Japan. It was a rich country, with five capitals,

fifteen superior prefectures, sixty-two prefectures, many cities, and, in the

south at least, a largely sedentary agrarian population. Militarily, however, it

proved no match for A-pao-chi's armies. It fell within two months, and its

king and nobility were removed to the Khitan court. Instead of annexing its

territory outright, A-pao-chi changed its name to the kingdom of Tung-tan

and appointed as its king his eldest son, the Chinese-influenced heir apparent

Pei.

Tung-tan became a vassal kingdom, retaining intact for the time being

its own administrative apparatus and even continuing to use its own reign

titles.

Why A-pao-chi acted so cautiously toward Po-hai is not entirely clear. He

may well have thought that the still-immature Khitan system of government

was not yet ready to cope with the very different and far more complex

problems of administering a large territory mostly settled by a sedentary

population and with many cities; he may simply have wished to avoid

antagonizing its numerous and potentially hostile population; and he may

have wished to carve out a permanent appanage for his own designated heir,

who,

as it turned out, was not favored by the Khitan nobles to succeed him as

khaghan.

Having swallowed Po-hai, A-pao-chi appears to have resumed his inten-

tion of expanding into northern China. In 926 there was a court coup in the

Later T'ang capital at Lo-yang. Li Ts'un-hsii had been militarily successful,

but his political organization was unstable. Early in 926 his armies in Ho-

nan and Hopei mutinied and killed him, replacing him with his adopted son

Li Ssu-yiian (reigned as Ming-tsung, 926—33), a provincial commander from

Hopei. The new Later T'ang emperor sent an envoy named Yao K'un to

report his accession to A-Pao-chi, who was still in Po-hai. Yao later wrote a

detailed account of his reception, which survives and from which we learn

that A-pao-chi announced his intention of first occupying Yu-chou and Ho-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

A-PAO-CHI BECOMES THE NEW KHAGHAN 67

pei and then making

a

settlement with the Later T'ang.

18

When the envoy

demurred, A-pao-chi toned down his territorial demands

to

simply Chen-

chou and Yu-chou

—

slightly more than the old province of Lu-lung.

The

envoy still refused.

At

this point A-pao-chi suddenly fell sick and died.

In

the subsequent confusion the invasion plan was forgotten, but had he lived

he had clearly intended a major invasion of Hopei.

At his death A-pao-chi was still only fifty-four. He had been leader of the

Khitan for only two decades, but he had transformed them from

a

local

if

powerful tribal confederation into

a

well-organized regime controlling

the

nomadic peoples of Mongolia and Manchuria, as well as the former territories

of

Po-hai.

His state had incorporated many Chinese from the border regions,

established cities for their residence, encouraged a diversity of industries and

settled farming, and accepted in principle the idea that the regime needed

a

dual form

of

organization, which would be able

to

administer the settled

farming population of the south and also to govern by more traditional means

the tribal peoples under their dominion.

A-pao-chi had encouraged the importation of Chinese systems of belief and

other aspects

of

culture. But

at

the same time he had tried

to

protect

the

Khitan culture, most importantly by providing his people with

a

writing

system. On his accession the Khitan had been illiterate, and written Chinese

was the only available medium for record keeping.

In

920 the first Khitan

script (the "large script,"

an

adaptation

of

the Chinese script

to

the very

different, highly inflected Khitan language) was presented, and by the end of

A-pao-chi's reign this script was widely used. In 925, when Uighur envoys

visited the court, the emperor's younger brother Tieh-la (whom A-pao-chi

recognized as the most clever member of

his

family) was entrusted with their

reception and, after learning their script (which was alphabetic), devised

a

second "small script" for Khitan.

Thus

by

the end

of

A-pao-chi's reign

it

was possible

to

operate

a

dual

system

of

government

in

which

the

northern tribal section conducted

its

business and kept documents

in

Khitan and the southern (Chinese) section

used both Chinese and Khitan. This would help the Khitan preserve their

authority and cultural identity, but

it

also made permanent the conflicting

elements within the Khitan elite, some of whom remained intransigent

in

their adherence to tribal values and institutions, whereas others adopted to a

greater

or

lesser degree the often different ideas and practices from China.

The "dualistic" nature

of

the state created

by

A-pao-chi may have been

a

18 For a detailed study of this fascinating document, which presents a vivid portrait of A-pao-chi, see Yao

Ts'ung-wu, "A-pao-chi

yii

Hou T'ang shih ch'en Yao K'un hui chien t'an hua chi lu,"

Wen

shih che

bsiieh

pao,

5

(1953), pp. 91-112; repr. with revisions

in

vol. 1 of his

Tung-pei

shlb lun u'ung (Taipei,

1959).

PP- 217-47-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

68 THE LIAO

strength,

as

the Khitan became more and more involved

in

the Chinese

world, but

it

was also inherently divisive.

THE SUCCESSION CRISIS AND THE REIGN OF T'AI-TSUNG

According to the arrangement A-pao-chi established in 916, the succession

should have passed automatically after his death to the designated heir appar-

ent Pei (900—37) without discord.

19

But this was not to be. The cultured and

refined Pei

—

a skilled painter, some of whose works were later included

in

the Sung imperial collection; an accomplished writer

in

both Khitan and

Chinese;

a

bibliophile with

a

large personal library and

a

taste for Chinese

culture; and an expert also

in

music, medicine, and prognostication

-

did

not appeal

to

the traditionally minded Khitan chieftains. A-pao-chi's per-

sonal authority had been sufficient to have him made heir apparent, in denial

of all Khitan custom and precedent, but even A-pao-chi seems later to have

realized that his younger son Te-kung was the better candidate, and once A-

pao-chi was dead

it

soon became clear that a simple transfer of the throne to

Pei was not in the cards.

The decisive factor

in

the succession was A-pao-chi's formidable widow,

Empress Ch'un-ch'in (later entitled Empress Dowager Ying-t'ien). She had

been a great power during A-pao-chi's lifetime, the first of

a

series of domi-

nant empresses that gives a special character to the Khitan regime. She had

played an open and active role. Early in the reign Ch'un-ch'in had devised a

plan for A-pao-chi

to

murder some

of

the tribal chiefs who opposed him.

Later she established her own military camp

(jardo),

commanded her own

army of 200,000 horsemen with which she maintained order when A-pao-chi

was away on campaign, and even herself organized campaigns against rival

tribes.

After A-pao-chi's death Ch'un-ch'in took control of all military and

civil affairs. When the time for his interment came, she declined to be buried

together with him according

to

custom, though more than three hundred

persons were buried with him

in

his mausoleum. Instead, she cut off her

right hand and had this placed

in

his coffin while she survived

to

act

as

regent,

for,

she claimed, her sons were still young and the country was

without a ruler. She remained in firm control while the succession was settled

and exercised great influence for many years to come.

Ch'un-ch'in herself had disapproved of the choice of

Pei,

and she used all

her influence to have him set aside in favor of his younger brother Te-kuang

(902—47), whom,

it

seems, even A-pao-chi had eventually acknowledged

19 See Yao Ts'ung-wu, "Ch'i-tan chiin wei chi ch'eng wen t'i te fen hsi,"

Wen shih che hsiieh

pao,

2(1931),

pp.

81

—iujrepr. in his

Tung-pa shih lun

ti'ung (Taipei, 1959), pp. 248-82, for a general discussion

of the succession problem under the Liao.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE SUCCESSION CRISIS AND THE REIGN OF T'AI-TSUNG 69

was the better candidate. Te-kuang was much more a potential leader in the

traditional Khitan tribal mold, although like Pei he was educated and a

capable calligrapher. He had distinguished himself

on

the battlefield during

the invasion of Ho-pei in 921-2 and played a major role as a commander in

the western campaign of

924—5.

Pei seems to have sensed danger for himself and helped persuade the

Khitan dignitaries at court that he should be passed over in favor of his

younger brother. Months went by with the succession still in doubt. Eventu-

ally, toward the end of 927 Pei himself approached his mother and formally

withdrew his claim. Te-kuang then succeeded to the throne. He is usually

known by his posthumous temple name of T'ai-tsung.

Pei was still, however, the ruler (Jen-huang wang) of Tung-tan, the

former state of Po-hai. After the prolonged succession problem, T'ai-tsung

regarded Pei as the greatest threat to his own authority and feared that he

would use the wealthy and populous Tung-tan state as a power base from

which to realize his frustrated claims to the Khitan throne. One at least of

Pei's consorts was a member of the Po-hai royal family. In 929 T'ai-tsung

ordered that the capital of Tung-tan and all its people be moved to Tung-

p'ing (present-day Liao-yang), which was designated the Southern Capital of

the Khitan state. Tung-tan was not abolished, but it was now more closely

integrated into the Khitan empire and gradually lost the special quasi-

autonomous status it had been granted in 926. Pei seems to have been placed

under surveillance. In 930 he fled by sea to China. He was received with

honor at the Later T'ang court of Ming-tsung in Lo-yang and lived there in

exile until 937, when he was murdered by Shih Ching-t'ang,

20

whom the

Khitan emperor had supported to overthrow the Later T'ang regime and who

remained a subservient puppet of the Khitan.

During T'ai-tsung's reign, actions against the border regions continued.

In 928 there was renewed trouble with the Wu-ku in the north. In 929 the

emperor's younger brother Li-hu was sent to attack the border area north of

Ta-t'ung, and in 933 he mounted an expedition against some Tangut tribes

that had still not submitted. But the most important aspect of the reign was

the gradual involvement of the Khitan in the political scene in north China.

The regime of the Later T'ang proved to be unstable. Its emperor, Ming-

tsung, had undertaken important reforms of government, restored the power

and influence of his bureaucrats, and built up palace armies that could

outweigh the forces of his provincial generals. But his reign ended badly,

with an attempted coup by one of

the

princes a few days before his death. His

20 Or according to another account by the last Later T'ang ruler, immediately before Shih Ching-t'ang

took Loyang. See IS, 72, p. 1211.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

70 THE LIAO

son Li Ts'ung-hou (temple name Min-ti) lasted only five months, before his

adoptive brother Li Ts'ung-k'o usurped the throne and killed him. At this

point the former Khitan heir apparent, Pei, who had been living under the

protection of Ming-tsung, wrote to his brother T'ai-tsung suggesting that he

invade the Later T'ang empire. This was in 934.

In 936 Li Ts'ung-k'o ordered the powerful governor of Ho-tung, Shih

Ching-t'ang, to be transferred to a post in Shantung where he would be

under closer court control. Shih Ching-t'ang rebelled, and Li Ts'ung-k'o led

an army to attack him in T'ai-yiian. Shih Ching-t'ang was another Sha-t'o

Turk, a son-in-law of the late emperor Li Ssu-yiian, and his rebellion led to

other provincial rebellions against the Later T'ang. Hard pressed by Li

Ts'ung-k'o, he now appealed to the Khitan emperor for military assistance.

T'ai-tsung personally led an army of fifty thousand cavalry across the border

through the Yen-men pass and defeated the Later T'ang army near Shih

Ching-t'ang's capital at T'ai-yiian. The T'ang regime speedily disintegrated.

In the eleventh month of 936, the Khitan invested Shih Ching-t'ang as

emperor of a new dynasty, the Chin. He was nothing more than a puppet of

the Khitan.

In 937, to curry favor with his new overlord, Shih Ching-t'ang murdered

the unfortunate Pei and, later in that year, agreed with T'ai-tsung that he

would treat him as his father, thus symbolically placing his dynasty on a

footing of inferiority to the Khitan. The Chin monarch seems to have realized

how completely he was entrapped by the Khitan and offered to pay a huge

annual subsidy to the Khitan to compensate for the return of the vital

prefectures of Yu-chou and Chi-chou that they had occupied. The Khitan

refused, and after some difficult negotiations in the next year the Khitan

received the cession of sixteen formerly Chinese prefectures, including a

broad belt from Ta-t'ung to Yu-chou. This new territory gave the Khitan

control of

all

the strategic passes that defended northern China, and a sizable

foothold in Hopei (see Map 3).

T'ai-tsung had achieved his father's territorial ambitions and, in the bar-

gain, had become the nominal overlord of a Chinese emperor. For the first

time a Chinese regime openly acknowledged the suzerainty of an alien dy-

nasty. The arrangement between T'ai-tsung and his puppet lasted only a few

years and collapsed after Shih Ching-t'ang died in 942. But the results were

far-reaching. The Khitan would hold on to most of the Sixteen Prefectures

until the end of their dynasty. Yu-chou became the new Southern Capital of

the Khitan (the former Southern Capital, center of Tung-tan, now became

the Eastern Capital and grew into a city even larger than the Supreme

Capital). A strong Khitan administration was imposed on the former Chinese

territory, and the Khitan state incorporated a very large Chinese population.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008