The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE REIGN OF MU-TSUNG 8l

sent envoys to congratulate the Liao on their victory, perhaps still hoping for

the elusive alliance. In the winter of

950

Shih-tsung himself led another foray

into Hopei.

The situation in China now underwent a major change. The rickety Han

regime at K'ai-feng collapsed at the beginning of 951, when its second

emperor was murdered and replaced by the chief general of his imperial army,

Kuo Wei (904—54), who was enthroned as emperor of

the

Chou. At the same

time Liu Ch'ung in T'ai-yuan broke away and established himself

as

ruler of

an independent state of Northern Han in Ho-tung. Once again the Khitan

faced two separate powers on their frontier with China.

The Chou got off to a bad start in their relations with the Liao. Their

envoys who came to inform the Liao of the change of dynasty brought with

them a letter, whose wording offended Shih-tsung, who promptly impris-

oned them. Later in the year the Chou attacked Liu Ch'ung, who sent an

envoy asking for Liao assistance and bearing a letter in which he humbly

called himself Shih-tsung's "nephew," thus accepting Liao superiority. Shih-

tsung sent envoys to invest Liu Ch'ung as emperor to cement their lord and

vassal relationship. The importunate Southern T'ang also renewed their re-

quest for an alliance against the Chou.

In the late autumn of

951

Shih-tsung took personal command of

a

south-

ern expedition against the Chou. But before the army set out, he fell victim

to yet another conspiracy, this time hatched by sons of A-pao-chi's younger

brothers, seeking once again to assert the claims to the succession of junior

lines of the royal family. The emperor, like many of the Khitan nobles, was

much addicted to drink, and when he and his entourage were helplessly

drunk after having sacrificed to his deceased father in preparation for the

expedition, Ch'a-ko, a son of A-pao-chi's younger brother An-tuan, mur-

dered him. The conspirators, however, had neglected to gain the support of

the courtiers and thus were summarily executed.

Shih-tsung was only thirty-three, and because he had no grown son, the

succession passed to the eldest son of T'ai-tsung, Ching (931-69; Khitan

name Shu-lii), who is known by his posthumous temple name Mu-tsung.

The southern campaign was abandoned.

THE REIGN OF MU-TSUNG, 95 I-969

The new emperor was not a distinguished monarch. Like his predecessor,

Mu-tsung was a heavy drinker who would sleep off his excesses for much of

the day, and his attention to public affairs was at best spasmodic. The

Chinese spoke of him as the "Sleeping Prince."

Problems with dissident members of the royal family continued. In 952

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

82 THE LIAO

Lou-kuo, a younger brother of Shih-tsung, hatched a conspiracy, and one of

his uncles and a prominent Chinese official plotted to defect to the Chou.

The plot was crushed and Lou-kuo was executed. In 953 another conspiracy,

led by a son of Li-hu named Wan, came to light. Several of the plotters were

executed, though Wan himself was pardoned. In 959 Ti-lieh, one of Lou-

kuo's co-conspirators, again plotted rebellion; and in 960 Wan's elder

brother Hsi-yin, the eldest son of Li-hu, was arrested for plotting a rebellion.

This time Li-hu himself was implicated and died in prison. For the rest of his

reign Mu-tsung's relatives were quiet.

Mu-tsung was not only inattentive to public business and self-indulgent,

spending inordinate time even by Khitan standards in the hunting field. He

was also violent, cruel, and capricious toward the members of

his

entourage,

especially when drunk. Indeed, toward the end of his reign, he ordered one of

his great ministers not to execute the sentences he passed when he was drunk

but to let him review them when he had sobered up. The annals of

his

reign

in the

Liao shih

are a sorry catalogue of casual cruelties.

Events elsewhere in China made this an unfortunate time for the Liao to be

under the rule of such an incompetent monarch, which virtually paralyzed

the dynasty. The new Chou regime, first under Kuo Wei (r. 951—4) and then

under the competent Ch'ai Jung (Shih-tsung, r. 954-9), was an altogether

better-organized and more powerful state than the earlier of the Five Dynas-

ties.

They finally broke the power of the provincial governors and firmly

reestablished strong central authority.

At the beginning of Mu-tsung's reign in 952 Liu Ch'ung, emperor of

Northern Han, asked for Liao assistance against the Chou. A force was sent

under Kao Mu-han that helped repel the Chou invaders. In 954 the Chou

again attacked Han, and a Khitan force was once more sent to their aid. The

Liao clearly valued their alliance with the Northern Han, for in that same

year they returned some Han troops who had been taken captive by mistake

and also assisted the Han in putting down local uprisings against the Han in

districts bordering the Liao. On more than one occasion, envoys from the

Han came to Liao to discuss strategic matters.

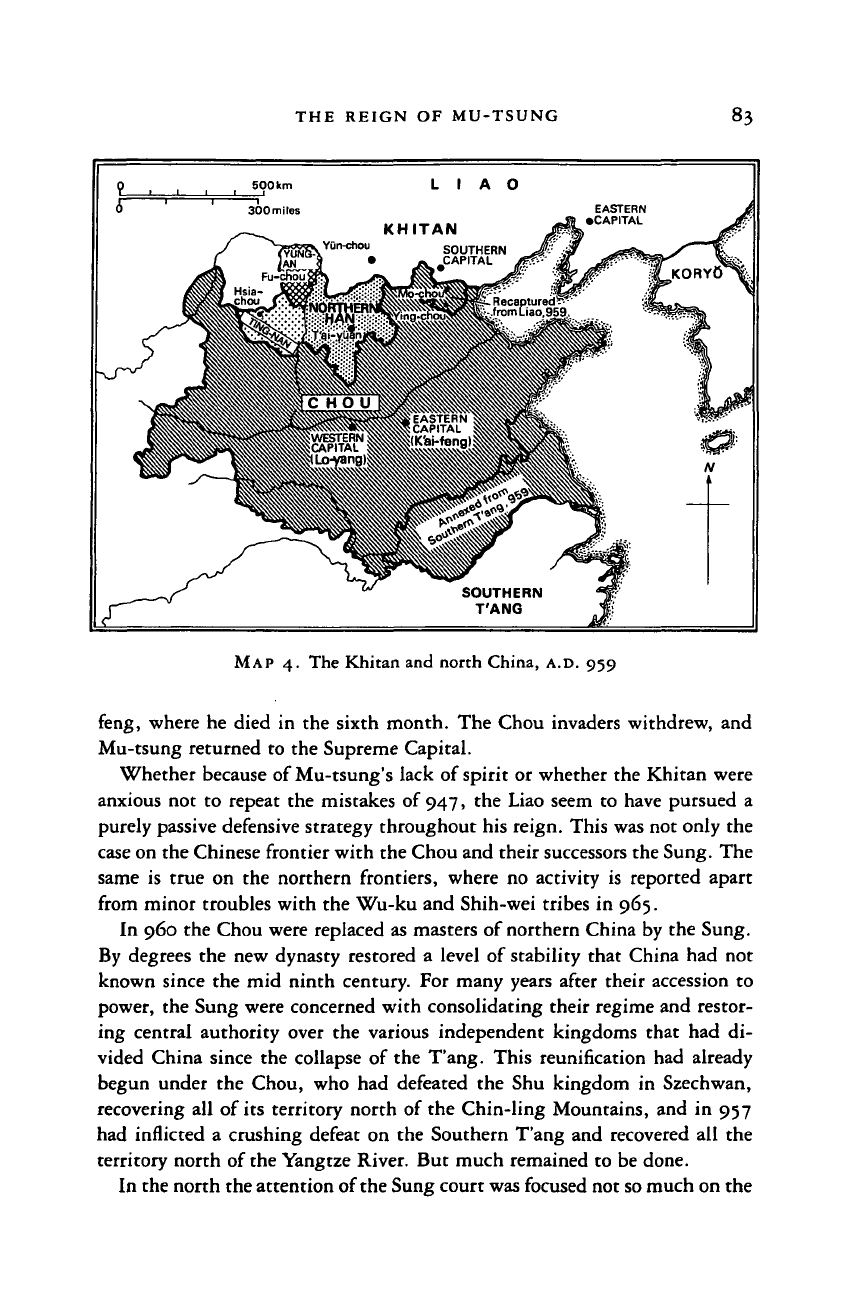

At the end of 958 the Han sent several envoys to report renewed invasions

by the Chou. Then in early summer of 959 the Chou attacked the Liao in

force. Their armies took the vital I-chin, Wa-ch'iao, and Yii-k'ou border

barriers in the fourth month and then in the fifth month recaptured Ying-

chou and Mo-chou, the southernmost of the Sixteen Prefectures (see Map 4).

The Liao armies retreated in the face of the onslaught. Mu-tsung roused

himself to come south to the Southern Capital to take command, and the

defenses were strengthened to await the Chou army. The confrontation did

not occur, however. The Chou emperor fell sick and had to return to K'ai-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE REIGN OF MU-TSUNG

8

3

0 500km

0' 300 m i les

/

TYUN

^pHsia-

FU

^

jx Yun-chou

8

•

'»L *

B

CHOU

§ WESTERNS

SCAPITAL

%

|Lo-yangl|

•j

L 1 A 0

KHITAN

SOUTHERN

A

-. CAPITAL

j£?

:

SOUTHERN

T'ANG

EASTERN

i

^ffl ^CAPITAL

jg-

i

MAP

4.

The Khitan and north China,

A.D.

959

feng, where

he

died

in

the sixth month. The Chou invaders withdrew,

and

Mu-tsung returned to the Supreme Capital.

Whether because of Mu-tsung's lack of spirit or whether the Khitan were

anxious not

to

repeat the mistakes of 947, the Liao seem

to

have pursued

a

purely passive defensive strategy throughout his reign. This was not only the

case on the Chinese frontier with the Chou and their successors the Sung. The

same

is

true

on the

northern frontiers, where

no

activity

is

reported apart

from minor troubles with the Wu-ku and Shih-wei tribes

in

965.

In 960 the Chou were replaced as masters of northern China by the Sung.

By degrees

the

new dynasty restored

a

level

of

stability that China had

not

known since the mid ninth century. For many years after their accession

to

power, the Sung were concerned with consolidating their regime and restor-

ing central authority over

the

various independent kingdoms that

had di-

vided China since the collapse

of

the T'ang. This reunification had already

begun under

the

Chou, who

had

defeated

the

Shu kingdom

in

Szechwan,

recovering

all of

its territory north

of

the Chin-ling Mountains, and

in

957

had inflicted

a

crushing defeat

on

the Southern T'ang and recovered

all the

territory north of the Yangtze River. But much remained to be done.

In the north the attention of the Sung court was focused not

so

much on the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

84

THE

LIAO

Liao

as on the

small

but

stubbornly independent Northern

Han

state

in

Shansi. The rulers of Northern Han, as we have seen, had already established

good relations with Shih-tsung

in the

early 950s, and the Liao continued

to

support them against

the

Sung.

For the

Liao their state was

an

invaluable

buffer zone and a strategic stronghold from which any attempt by the Sung

to

strike into

the

occupied prefectures

of

northern Ho-pei could easily

be out-

flanked. When

in

963

the

Northern

Han

were attacked

by the

Sung, they

immediately appealed

for aid

from

the

Khitan.

In 964 a

Liao army

was

dispatched, which helped repel

the

Sung invaders.

The

Liao also reacted

against attempts

by the

Sung

to

consolidate

the

border gains that had been

achieved

by the

Chou armies

in

959.

In

963

and

again

in 967

there were

minor skirmishes on the border to prevent the Sung from fortifying the I-chin

pass that

had

been overrun in 959.

But

there were no major hostilities.

In

969

Mu-tsung

was

murdered.

He had

spent

the

whole

of the

first

month

of

the year

in a

furious drinking bout during which he again abused

members of

his

entourage.

In

the second month he attended

to

business long

enough

to

invest as his vassal the new ruler of Northern Han, Liu Chi-yiian.

But he then again began to act violently and irrationally, butchering some of

his bodyguards. Finally, driven

to

extremes,

six of

his personal attendants

murdered him during the night. The Liao were well rid of a bloodthirsty and

totally unpredictable tyrant.

The succession this time passed

off

without incident.

All of

A-pao-chi's

brothers were now dead,

and

the energies

of

their descendants seem

to

have

been exhausted

in

the round of conspiracies earlier in the reign. No objection

was raised when the throne passed back

to

the senior royal line. Shih-tsung's

eldest son was already dead,

and

the succession went

to

his second son Hsien

(948-82; Khitan name Ming-i) who reigned from 969

to

982

and is

known

by his temple name Ching-tsung.

THE REIGN OF CHING-TSUNG, 969-982:

CONFRONTATION WITH SUNG

By

the

time

the new

emperor Ching-tsung came

to the

Liao throne,

the

situation

in

China

had

been completely transformed.

The

Chou dynasty,

which

had

made rapid strides toward reestablishing political stability

in

China, had been crippled by the unexpected death of

its

emperor, Shih-tsung

(Ch'ai Jung),

in 959 and the

succession

of

a six-year-old boy.

The boy was

toppled

in a

military coup led by

a

general named Chao K'uang-yin (known

by his temple name T'ai-tsu;

r.

960—76), who in 960 set up a new dynasty of

his own, the Sung. Sung T'ai-tsu finally broke the local power of

the

provin-

cial commanders, who had been the real power holders in China since the late

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE REIGN OF CHING-TSUNG 85

ninth century, and gave his new dynasty a strong central government under

firm civilian control. One by one T'ai-tsu eliminated and brought under

Sung control the independent states that had divided up China south of the

Yangtze; in 963 Ch'u in the central Yangtze basin, in 965 Later Shu in

Szechwan, in 971 Southern Han in Kwangtung and Kwangsi, and in 975

Southern T'ang in Kiangsu, Anhwei, and Kiangsi. When in 976 his younger

brother K'uang-i (temple name T'ai-tsung, r. 976-97) succeeded him to the

throne of Sung, there remained only two independent regimes still to be

incorporated into the empire: Wu-Yiieh in Chekiang and Northern Han in

Shansi. Wu-Yiieh surrendered to the Sung in 978. Only the Northern Han

remained.

The Northern Han, the last remnant of

the

Sha-t'o Turkish domination of

Shansi, had been closely involved with the Liao since its foundation in 951,

when the first Northern Han emperor had been invested with his title by

Shih-tsung of the Liao. Even the indolent Mu-tsung had understood the

importance of the Han to the Liao's defensive strategy and had bestirred

himself to help the Han beat off a Sung attack in the early 960s. An

independent Han was greatly to the advantage of the Liao. It reduced the

Liao—Sung frontier to a comparatively short stretch in the Ho-pei plain and

gave Liao an ally that could threaten any attempt by the Sung to strike north

at

Liao

across the Ho-pei plain by outflanking them from an almost impregna-

ble base in the highlands of northern Shansi. The Northern Han was, how-

ever, a small state and quite unable, in spite of the professionalism and

bravery of its troops, to withstand a full-scale war with Sung, except by

relying on its alliance with the powerful Liao empire.

The Han carefully cultivated this alliance. In 971, soon after Ching-

tsung's accession, they began to send regular monthly courtesy missions to

the Liao court to ensure support. The Sung, nevertheless, were determined to

conquer the Northern Han and in 974 began negotiations with the Liao to

prepare a peace treaty, so as to ensure the Liao's neutrality when they attacked

the Han.

Beginning in 975 the Sung and Liao began to exchange regular diplomatic

missions. In 977 the Sung even established five official border marshals to

supervise trade with the north. Sung T'ai-tsung may have hoped to stabilize

the border and also to cause a rift between the Liao and their Northern Han

vassal, but if

so

his efforts were a failure.

In the last year of T'ai-tsu's reign, 976, the Sung had invaded Northern

Han. The Han asked the Liao court for assistance, and an army was sent that

enabled the Han to repel the invasion. The next year saw a renewed Sung

attack on the Han that brought another request for assistance. The Khitan

again sent troops and cavalry to help the Han defense.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

86 THE LIAO

In 979, after the surrender of Wu-Yiieh, Sung T'ai-tsung mounted a large-

scale invasion of the Han, now the last remaining independent state. The

Liao sent an envoy to the Sung court demanding an explanation and were told

bluntly to stay out of the conflict or they too would be attacked. In the early

spring of 979 the Liao sent armies to the assistance of the Han, but the Sung

armies intercepted them. The Liao suffered crushing defeats and heavy casual-

ties.

In the sixth month the Sung armies took T'ai-yiian, and the Northern

Han emperor surrendered to them. The last of the independent states had

been crushed and annexed.

Sung T'ai-tsung, in the full

flush

of victory, now, however, made

a

most im-

prudent decision. Going against the advice of all his commanders and without

giving his already exhausted and overextended forces any chance to recover

their strength and consolidate their position, he turned east through the passes

in the T'ai-hang range and invaded the Khitan territory in northern Ho-pei,

intent on recovering the Sixteen Prefectures taken by the Khitan in 937.

Advancing to besiege the Liao Southern Capital (at modern Peking) Sung

T'ai-tsung won some preliminary battles with the Khitan forces, but then in

the seventh month the main Sung and Liao armies met in a crucial pitched

battle on the Kao-liang River southwest of the capital.** It was a total

disaster for the Sung, who suffered enormous casualties. The Liao took many

prisoners and captured huge quantities of weapons and armor, baggage,

equipment, money, and provisions. The unfortunate Sung emperor, who had

been wounded, lost contact with his army, fled the battlefield alone, and

made his way south to safety riding in a donkey cart. Some of his generals,

thinking he was dead, wondered whether they should enthrone the son of the

Sung founder in his place. What had begun as a victorious invasion of

Northern Han ended in an ignominious rout.

For the time being the Liao had the initiative. In 980 Ching-tsung took

command in person of an offensive against the Sung in Ho-pei that recap-

tured the Wa-ch'iao barrier and defeated a Sung army. In 982 he launched

another campaign, but this time the Liao armies were defeated, and Ching-

tsung was forced to withdraw.

The result of these events was a complete change in the relationship

between the Liao and the Sung, which no longer revolved around the buffer

state of

Han.

The two great empires now faced each other along a continuous

frontier stretching from the sea to the upper elbow of the Yellow River. And

the Liao continued in possession of the Sixteen Prefectures, which continued

to provoke revanchist feelings at the Sung court. It was only a matter of time

before warfare broke out again.

24 On this battle, see Fu, Liao shih

ts'ung

k'ao,

pp. 29—35.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE REGENCY OF EMPRESS DOWAGER CH'ENG-T'lEN 87

These troubles with the Sung were not the only military problems of

Ching-tsung's reign. There were border problems with the Tanguts in 973,

and with the Jurchen in the northeast, who invaded and looted Liao territory

in 973 and again in 976. Both peoples were to cause trouble for the Liao for

many years to come.

In 981 there was an attempted coup aiming to enthrone a son of Hsi-yin,

the son of Li-hu who had been imprisoned under Mu-tsung but later par-

doned when Ching-tsung came to the throne. A group of captured Chinese

soldiers managed to enthrone Hsi-yin's son, but the plot failed. Hsi-yin was

forced to commit suicide, and his son was executed.

In the autumn of 982 Ching-tsung, though still a young man, suddenly

fell sick during a hunting trip and died in his camp. In his dying testament

he left the throne to his eldest son Lung-hsii (r. 982—1031; temple name

Sheng-tsung). The new emperor was only eleven years old, and so his

mother, Ching-tsung's empress Jui-chih (later entitled Empress Dowager

Ch'eng-t'ien), was appointed regent.

THE REGENCY OF EMPRESS DOWAGER CH'ENG-T'lEN

Empress Jui-chih was another of the succession of remarkable women who

played a notable role in Liao public life.

25

One of the reasons for this was the

most unusual marriage structure of the Liao royal family, who took their

wives from a single consort clan, the Hsiao, who also provided consorts for

royal princesses and enjoyed the hereditary right to various influential of-

fices.

26

The royal brides, therefore, always came from families deeply in-

volved in government and politics. Jui-chih was no exception. She was the

daughter of Hsiao Ssu-wen (d. 970), appointed the northern commissioner

for military affairs

(pet-yuan shu-mi shih)

and northern prime minister

(pei-fu

tsai-hsiangY

1

at the beginning of Ching-tsung's reign, and she was made

empress only two months after his appointment. The empress had already

been influential in politics during Ching-tsung's life. Now she was left in

control of the Liao empire. Although empress dowager, she was not a middle-

aged lady, as the title suggests. She had just turned thirty years old.

The real power during the first half of Sheng-tsung's long reign, until her

death in 1009, was in the hands of the empress dowager and three remark-

25 For his biography, see LS, 71, p. 1201-2.

26 On this sytem, see Karl A. Wittfogel and Feng Chia-sheng, History of

Chinese

society,

Liao (907—

112)),

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, n.s., vol. 36 (Philadelphia, 1949), pp.

191-2,

206—12 (hereafter cited as Wittfogel and Feng); and Jennifer Holmgren, "Marriage, kinship

and succession under the Ch'i-tan rulers of the Liao dynasty (907-1125)," Young Poo, 72 (1986),

pp.

44-91.

27 LS, 8, pp. 90. For his biography, see LS, 78, pp. 1267-8.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

88 THE LIAO

able ministers, two of whom were Chinese. All three had been in power since

the Sung invasion of 979, and the empress was accustomed to working with

them.

The senior figure was Shih Fang (920-94), *

8

a native of Chi-chou in

northern Hopei. He had been a scholarly prodigy, who was given the degree

of

chin-shib

about 938, as the first "graduate" recorded under the Khitan. His

"degree" in fact was almost certainly a personal honor, as the examination

system was not permanently established for another half-century. When T'ai-

tsung occupied K'ai-feng in 947, he was given charge of ritual and drafting

edicts and subsequently held a succession of posts at the Southern Capital

broken by more than a decade as a Han-lin scholar under Mu-tsung. He was

highly regarded by Ching-tsung and was steadily promoted until in 979 he

became northern prime minister. On Sheng-tsung's accession in 983 he

attempted to retire but was refused and was given the additional post of head

of the secretariat

(chung-shu

ling).

Shih Fang became an important figure,

setting the tone for a series of reforms covering the recruitment of officials

and the easing of the tax burden on the people and winning wide respect. In

990 he again requested leave to retire and was permitted to reside perma-

nently at the Southern Capital. In 993 he selected Han Te-jang as his own

successor and was made honorary viceroy of the supreme capital. He died

shortly afterward.

Han Te-jan (941

—1011)

29

was also Chinese and also from a Chi-chou

family, but his background was very different from that of Shih Fang. His

grandfather, Han Chih-ku,

3

° had been captured by the Khitan as a child and

became a member of the household of A-pao-chi's empress. He soon gained

A-pao-chi's confidence. The Khitan leader put him in charge of an office to

control his Chinese subjects

{Han-erh ssu)

and gave him responsibility for

court ceremonial. He and another surrendered Chinese, K'ang Mo-chi,

3

' who

advised A-pao-chi on the establishment of Chinese cities, were each given

high-sounding titles,

tso

p'u-yeh

and

tso

shang-shu,

respectively, and remained

influential throughout A-pao-chi's reign. After K'ang's death in 926, Han

Chih-ku, now president of

the

Secretariat (Chung-shu ling), held high office

until he died early in T'ai-tsung's reign. He was the founder of the most

powerful Chinese family in the Khitan state.

28 For his biography, see LS, 79, pp. 1271—2.

29 For his biography, see LS, 82, pp. 1289—91, under his later name Yeh-lu Lung-yiin. He appears in the

histories under a series of names. In 1001 the emperor gave him the new personal name Te-ch'ang. In

1004 he was given the imperial surname Yeh-lii and in 1010, just before his death, the new personal

name Lung-yiin. He had no son, and the descendants of

his

brothers, who remained influential until the

fall of the Liao, continued to bear the surname Han. On his family, see Li Hsi-hou, "Shih lun Liao tai Yii-

t'ien Han shih chia tsu te li shih chi wei," Sung Liao Chin shih lun

U'ung,

1 (1983), pp. 251-66.

30 For his biography, see LS, 74, p. 1233.

31 LS, 74, p. 1230.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE REGENCY OF EMPRESS DOWAGER CH'ENG-T'lEN 89

His son Han K'uang-ssu (d. 98i)

3S

was

a

favorite of A-pao-chi's widow,

the empress dowager Ying-t'ien, and became the director {hsiang-wen,

a

Khitan tribal title) of A-pao-chi's ancestral temple. He was closely involved

with the royal family, survived participation

in

Hsi-yin's conspiracy under

Mu-tsung in 960, and became an intimate of Ching-tsung in the 960s while

he was still heir apparent.

On his

accession

to

the throne Ching-tsung

appointed him viceroy, first of the Supreme Capital and then of the Southern

Capital, and also commissioner for military affairs

{shu-mi

shih). During the

Sung invasion

of

979 Han K'uang-ssu was defeated and abandoned

his

troops. Ching-tsung wished to execute him, but the empress and her family

interceded

to

save him.

In

981 Han K'uang-ssu was appointed "commis-

sioner for chastisement" of the southwest and died shortly afterward. He not

only enjoyed strong personal influence with Ching-tsung; he also was

an

immensely powerful nobleman, with his own private fortress city, which

later became

a

regular prefecture in 991. He also left five sons, who laid the

foundation of

a

century of political power for the Han family.

33

Han K'uang-ssu's two eldest sons, Han Te-yiian (d. ca. 980) and Han Te-

jang (941-1011), both had served

in

Ching-tsung's princely household

before his succession. Han Te-yiian held various offices between 960 and

979 and made for himself something of a reputation for corruption before

his death around 980.

34

Han Te-jang

35

was chosen

by

Ching-tsung

to

succeed his father Han K'uang-ssu as viceroy of the Supreme Capital and

later of the Southern Capital. He distinguished himself in the defense of the

Southern Capital against

the

Sung invaders

in

979 and was appointed

commissioner for military affairs {shu-mi shih) of the Southern Administra-

tion. When Ching-tsung died, he and Yeh-lii Hsieh-chen received his will

and were responsible for enthroning the young Sheng-tsung. The empress

dowager favored and respected him greatly, and Han Te-jang steadily be-

came the most powerful individual in the Liao empire. Sung sources, proba-

bly maliciously, suggest he was the empress dowager's lover. Eventually

in

1004 he was given the royal Yeh-lii surname. His three younger brothers

also filled high positions. The most important of them was Han Te-wei,

a

general who succeeded his father as punitive commissioner for the south-

west and from 983 until the end of the century was mainly responsible for

dealing with the Tanguts.'

6

The other most powerful persons

in

the first years of Sheng-tsung were

32 LS, 74, p. 1234.

33 See Lo Chi-tsu, Liao Han

ch'en

shih hit piao; repr. as no. 35 in vol.

4

of Liao shih hui pint, ed. Yang

Chia-lo (Taipei, 1973), item 35, pp. 2—4.

34 LS, 74, p. 1235.

35 For his biography, see LS, 82, pp. 1289—91.

36 On Han Te-wei's family and their semi-Khitan status, see Wittfogel and Feng, p. 220 and n. 420.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

90 THE

LIAO

both Khitan and members of the imperial clan. Yeh-lu Hsieh-chen

37

was the

grandson of the commander in chief

(yii-yiieh)

Yeh-lu Ho-lu and had been

recommended to Ching-tsung in 969 by the empress dowager's father, the

commissioner for military affairs

(shu-mi

shih),

Hsiao Ssu-wen. Ching-tsung

was greatly impressed by him and married him to a niece of the empress. He

distinguished himself

in

the war with Sung in 979 and won the respect of the

empress dowager. Shortly after Sheng-tsung's accession, she organized a most

unusual ceremony to ensure his loyalty. The child emperor and Yeh-lii Hsieh-

chen swore a pact of friendship in her presence, exchanging bows, arrows,

saddles, and horses.

38

The empress dowager subsequently gave Hsieh-chen

many important responsibilities, making him northern commissioner for

military affairs

(sbu-mi

shih).

He remained influential until his death during

the campaign against Sung in 1004. Another Khitan who helped stabilize

the leadership was Yeh-lii Hsiu-ko, the commander in

chief,

who held this

vital post from 984 until his death at the end of 998 and played a role in all

the campaigns of this period.

39

A measure of Han Te-jang's steadily emerging dominance can be seen in

the fact that when Yeh-lu Hsiu-ko died in 998, Han succeeded to his post as

yii-yiieh, and when Hsieh-chen died a year later he also took his post as

northern commissioner for military affairs, holding both of these posts in

addition to his original office as southern commissioner for military affairs.

From 999 to ion Han held more complete civil and military control over

the Liao government, both of its Chinese and Khitan components, than any

minister had before or after him.4°

But while Ch'eng-t'ien

was

alive, there was no question who

was

ultimately

in control; these great ministers were the empress dowager's men, and the new

emperor

was

thoroughly dominated by his mother,

who

continued to browbeat

and sometimes strike him in public even when he was

a

grown man. Immedi-

ately after the new emperor's succession she took an extraordinary step to

ensure her power as regent. Before his formal installation on the throne, a Liao

ruler normally went through the important Khitan religious ritual of "rebirth"

(tsai-sheng),

in the course of which he was symbolically reborn."" This con-

firmed the new emperor's right to rule in the eyes of the Khitan tribal aristoc-

37 For his biography, see LS, 83, p. 1302.

38 LS, 10, p. in.

39 For his biography, see LS, 83, p. 1299.

40 See WanSsu-t'ung, Liao la

ch'en

menpiao; repr. as no. 33 in vol. 4 of Liaoshib

hui-pien,

ed. YangChia-lo

(Taipei, 1973), item 33, pp. 8-9. Han held all three posts from 999 to the seventh month of 1002,

when another Chinese, Hsing Pao-p'u, became the southern shu-mi ihih.XJpon Hsing's death early in

1004,

however, this post reverted to Han Te-jang.

41 LS, 53, pp. 979-80; translated by Wittfogel and Feng, pp. 273-4. According toLS, 116, p. 1537,

it was supposed to be repeated every twelve years. See Shimada Masao,

Ryocbo

shi no kenkyu (Tokyo,

1979),

pp. 339—47; Wang Min-hsin, "Ch'i-tan te 'ch'ai ts'e i' yu' ts'ai sheng i," Ku kung t'u sbu cbi

k'an,

3, no. 3 (1972), pp. 31-52.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008