The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

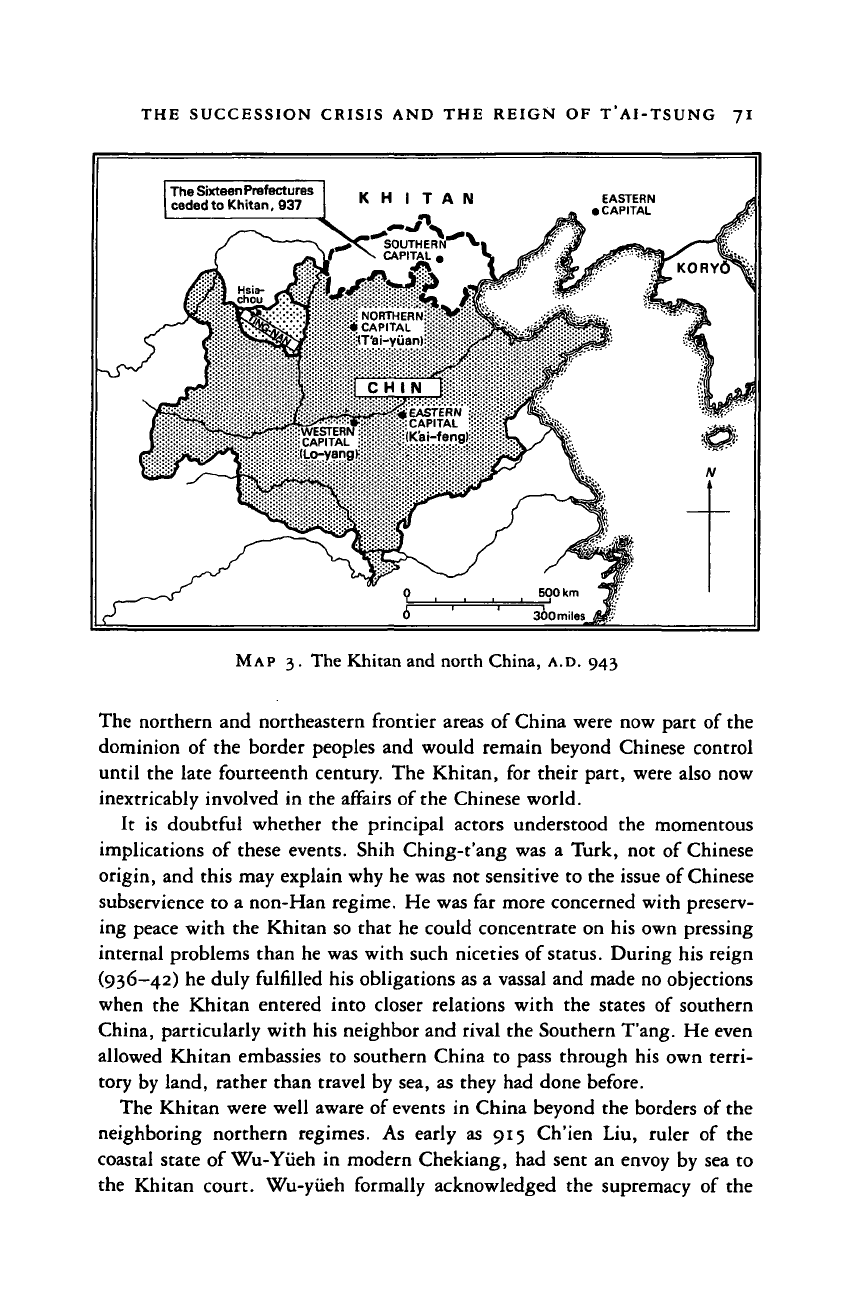

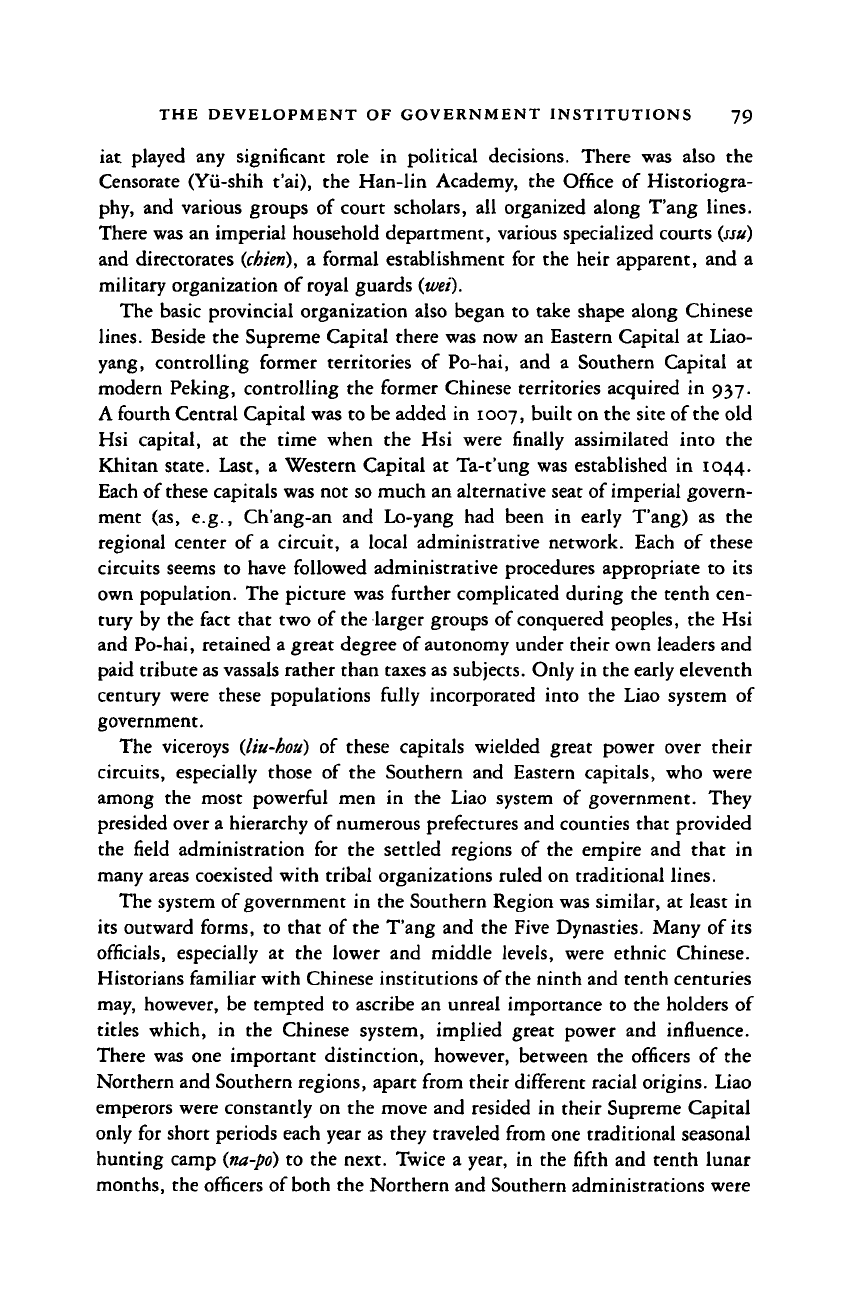

THE SUCCESSION CRISIS AND THE REIGN OF T'AI-TSUNG 71

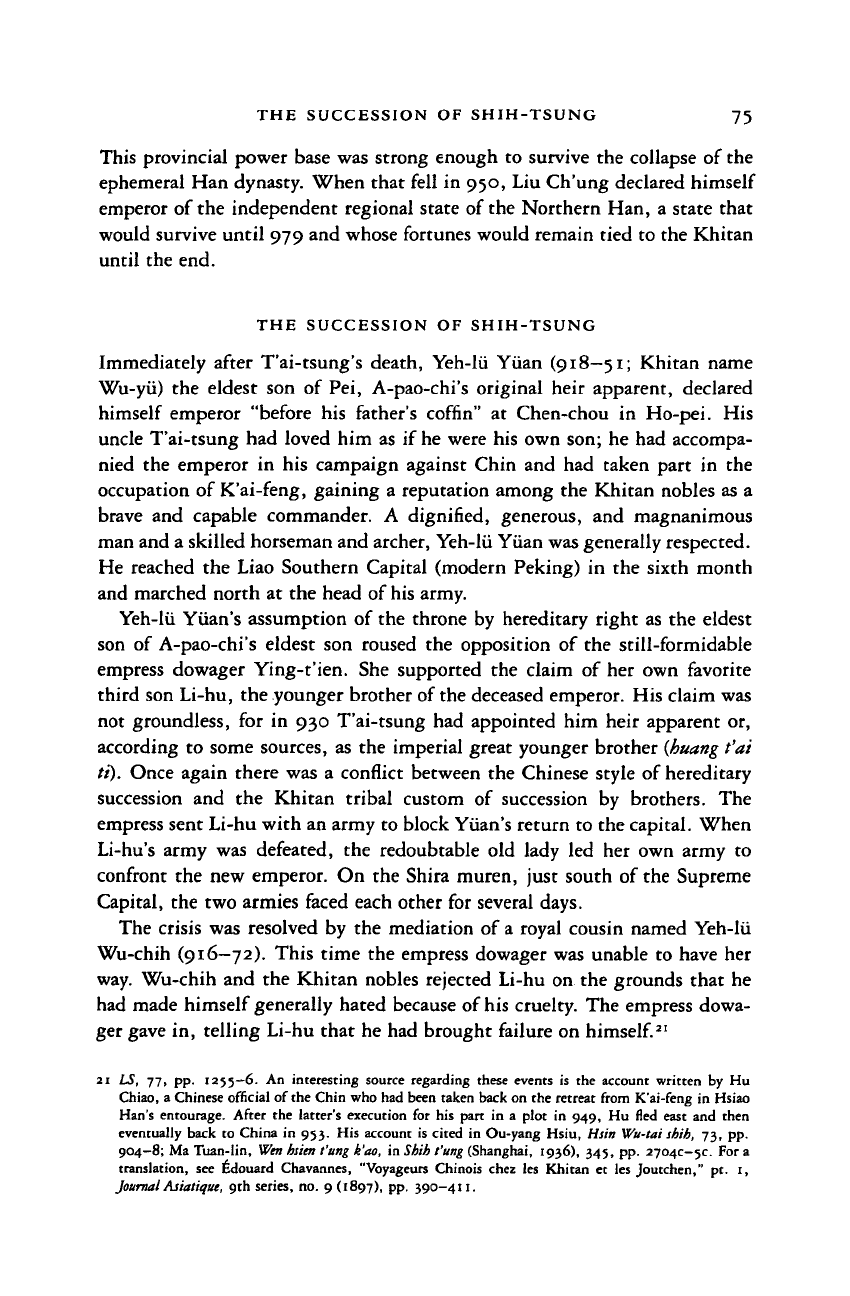

The

Sixteen

Prefectures

ceded

to Khitan, 937

*EASTERN

CAPITAL

SSST JK'ar-fengl

(Lo-yangl-

MAP

3. The Khitan and north China,

A.D.

943

The northern and northeastern frontier areas of China were now part of the

dominion of the border peoples and would remain beyond Chinese control

until the late fourteenth century. The Khitan, for their part, were also now

inextricably involved in the affairs of the Chinese world.

It is doubtful whether the principal actors understood the momentous

implications of these events. Shih Ching-t'ang was a Turk, not of Chinese

origin, and this may explain why he was not sensitive to the issue of Chinese

subservience to a non-Han regime. He was far more concerned with preserv-

ing peace with the Khitan so that he could concentrate on his own pressing

internal problems than he was with such niceties of status. During his reign

(936—42) he duly fulfilled his obligations as a vassal and made no objections

when the Khitan entered into closer relations with the states of southern

China, particularly with his neighbor and rival the Southern T'ang. He even

allowed Khitan embassies to southern China to pass through his own terri-

tory by land, rather than travel by sea, as they had done before.

The Khitan were well aware of events in China beyond the borders of the

neighboring northern regimes. As early as 915 Ch'ien Liu, ruler of the

coastal state of Wu-Yiieh in modern Chekiang, had sent an envoy by sea to

the Khitan court. Wu-yiieh formally acknowledged the supremacy of the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

72 THE LIAO

successive regimes in north China. Their motives for also opening relations

with the Khitan were chiefly commercial: They wished to protect their trade

interests in Po-hai and Korea. The Khitan, for their part, sought access to

the seaborne trade with Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, to obtain

exotic articles, spices, and luxury

goods.

The Southern T'ang also established

relations with the Khitan, but in their case the motivation was political.

They wished to form an alliance with the Khitan against the Later T'ang. The

king of Southern T'ang and the Khitan emperor addressed one another as

brothers, thus giving Southern T'ang superior status in Khitan eyes to their

northern neighbors, the Later T'ang. At a single audience in 937 T'ai-tsung

received envoys from the Later T'ang, from the semi-independent governor of

T'ai-yiian, Liu Chih-yiian, and from the newly enthroned emperor of South-

ern T'ang. The Khitan were thus closely involved in the complex interstate

politics of the various independent regimes in China.

Relations with Southern T'ang were not purely formal. The southern court

provided crucial intelligence to the Khitan about developments in the Chin

in 940, 941, and 943. After the fall of Chin and the Khitan attempt to set up

a regime at K'ai-feng in 947 had ended in failure and withdrawal, the

Southern T'ang again suggested a military alliance against the short-lived

Han regime (948-51) that succeeded the Chin. And as late as 957 they again

provided the Liao with military intelligence about the Chou regime in the

north, which was currently threatening the Southern T'ang.

The relations between the Khitan and the southern states of Wu-Yiieh and

Southern T'ang were at their height in the late 930s and 940s; for a while

Wu-Yiieh even used the Khitan calendar. But T'ai-tsung's invasion showed

the south what a potential threat the Khitan posed. After the accession of the

Liao emperor Mu-tsung in

951,

the politically inactive Khitan leader showed

no interest in intervening in the everlasting power struggles among the

Chinese states. Thereafter both diplomatic contacts and trade with the south-

ern courts fell off dramatically. They deteriorated even further after 954,

when Mu-tsung's uncle, who had been sent as an envoy to Southern T'ang,

was assassinated. He thus refused to send any further envoys, although

Southern T'ang envoys reached the Liao in 955 and again in 957, still seeking

help against the Chou.

After the death of Shih Ching-t'ang in 942, relations between the Khitan

and the Chin rapidly deteriorated. Shih Ching-t'ang may have been a Khitan

puppet, but he had quietly restored the authority of his dynasty over the

fractious provinces, strengthened the structure of government, and built up a

strong centralized army. His successor, Shih Ch'ung-kuei (temple name

Ch'u-ti; reigned 942—6), came under the influence of a violently anti-Khitan

court faction led by the commander of the imperial army Ching Yen-kuang,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE SUCCESSION CRISIS AND THE REIGN OF T'AI-TSUNG 73

and he openly repudiated the former supremacy of T'ai-tsung and his "North-

ern Dynasty." In 943 Shih Ch'ung-kuei abolished the privileges of Khitan

merchants at the Chin capital, K'ai-feng, confiscated their property, and sent

their representative, who also managed trade in Chin on behalf of

the

Khitan

court, back home bearing an insulting letter to T'ai-tsung.

T'ai-tsung decided to invade. At the end of

944,

Khitan forces crossed the

border of Hopei at several points, followed by T'ai-tsung's main army. The

fighting dragged on for three years, and not all of it went the Khitans' way.

In the late spring of

945

the invading army was seriously defeated, and T'ai-

tsung himself had to flee the battlefield mounted ignominiously on a camel.

But the Khitan persisted, wearing down the Chin armies. The province of

Ho-pei, where most of

the

fighting took place, was devastated. The outcome

was decided at the end of

946

when Tu Ch'ung-wei, the Chin commander in

chief and uncle of the emperor, surrendered. T'ai-tsung was able to enter the

capital, K'ai-feng, without meeting any resistance.

At the beginning of 947, T'ai-tsung made a triumphal entry into K'ai-

feng riding in the imperial carriage, took up his residence in the palace of the

Chin emperor, and held court in the ceremonial audience hall, demanding

the attendance of the remaining Chin courtiers. The Chin emperor and his

family were sent in exile to the Liao Supreme Capital in Manchuria. The

Chin imperial armies, after the surrender of Tu Ch'ung-wei, were disarmed

and disbanded, and their cavalry horses were confiscated. T'ai-tsung formally

announced a general act of grace, adopted a new dynastic name for the

Khitan state

—

now to be known as the Greater Liao

—

and adopted a new

reign title and a new calendar (which had in fact been devised under the Chin

in 939). The new reign title he chose was Ta-t'ung, "Great Unity," and this

publicly proclaimed that he was determined to make himself emperor of all

north China. The Liao court diarists recorded that more than a million

households of the Chin population had been incorporated into their empire.

But the Chinese population thought otherwise. The Khitan army had

brought no adequate supplies with them and now looted the capital and

plundered the countryside in search of food and forage. Oppressive levies

were imposed on the citizens of K'ai-feng, and everywhere there was resent-

ment and fear of the invaders' unbridled violence. The populace began to

attack the Khitan; mutinies and uprisings broke out all over Ho-pei. The

Khitan were totally unprepared to govern such a vast territory, inhabited by a

hostile sedentary population that far outnumbered them. T'ai-tsung com-

plained to his entourage: "I never knew that the Chinese could be so difficult

to govern as this!"

The Khitan now began to loot the capital thoroughly. It

was

decided to take

back to Manchuria the entire body of Chin officials. This proved impossible,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

74 THE LIAO

but in the third month of 947 they began shipping off to the Supreme Capital

the personnel of the main ministries, the palace women, eunuchs, diviners,

and artisans in their thousands; books, maps; astronomical charts, instru-

ments, and astronomers; musical treatises and ceremonial musical instru-

ments; the imperial carriages and ritual impedimenta; the weapons and armor

from the arsenals; and even the copies of the Confucian classics engraved on

stone slabs. While T'ai-tsung stripped bare the palace and government offices,

his troops continued to pillage the city and surrounding countryside.

The Khitan, already harried by popular resistance and guerrilla attacks,

were now faced with a more severe threat. Liu Chih-yuan, the governor of the

fiercely independent Sha-t'o stronghold of T'ai-yiian who had stood aside

when the Khitan invaded Hopei, refused to acknowledge T'ai-tsung as

emperor or to attend his "court" in K'ai-feng. In the second month of 947 he

declared himself the emperor of a rival new dynasty, the Han. Discontented

elements in the neighboring provinces rallied to his banner, posing an imme-

diate threat to K'ai-feng and Lo-yang. T'ai-tsung was now in a precarious

position, facing not only widespread guerrilla resistance, local uprisings, and

mutinies throughout Ho-pei but also the threat of

a

full-scale military con-

frontation with the only major commander in the north whose forces had

remained intact after T'ai-tsung had disbanded the Chin imperial army.

T'ai-tsung wisely decided to withdraw to the north, to "avoid the heat of

summer" as he claimed but, in reality, to avoid being trapped with his army

in an indefensible position deep in hostile territory. He had enjoyed his

occupation of the capital at K'ai-feng for only three months. In the fourth

month the Liao armies and his vast baggage train began to withdraw, con-

stantly harassed en route by Chinese attacks. The invasion had plainly been a

major miscalculation. T'ai-tsung himself admitted that he had made grave

mistakes in permitting the looting of the countryside, in imposing harsh

penal levies on the cities, and in failing to deal firmly with the provincial

governors, who were still a key factor in the power structure of northern

China. Moreover, his campaign had never won general approval among the

Khitan nobility. Never again would a Liao emperor seriously plan a campaign

of conquest in China.

Shortly before reaching Liao territory in northern Ho-pei, T'ai-tsung, who

was still only forty-five, suddenly fell ill and died at Luan-ch'eng (south of

present-day Shih-chia chuang, Hopei). The Liao, having suffered a major

disaster in their invasion of

China,

now faced yet another succession crisis at

home.

Meanwhile, Liu Chih-yuan entered K'ai-feng in the sixth month and

established the shortest-lived of the Five Dynasties, the Han (947-50). He

left his provincial capital at T'ai-yiian in the hands of

his

cousin Liu Ch'ung.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE SUCCESSION OF SHIH-TSUNG 75

This provincial power base was strong enough to survive the collapse of the

ephemeral Han dynasty. When that fell in 950, Liu Ch'ung declared himself

emperor of the independent regional state of the Northern Han, a state that

would survive until 979 and whose fortunes would remain tied to the Khitan

until the end.

THE SUCCESSION OF SHIH-TSUNG

Immediately after T'ai-tsung's death, Yeh-lii Yuan

(918—51;

Khitan name

Wu-yii) the eldest son of Pei, A-pao-chi's original heir apparent, declared

himself emperor "before his father's coffin" at Chen-chou in Ho-pei. His

uncle T'ai-tsung had loved him as if he were his own son; he had accompa-

nied the emperor in his campaign against Chin and had taken part in the

occupation of K'ai-feng, gaining a reputation among the Khitan nobles as a

brave and capable commander. A dignified, generous, and magnanimous

man and a skilled horseman and archer, Yeh-lii Yuan was generally respected.

He reached the Liao Southern Capital (modern Peking) in the sixth month

and marched north at the head of his army.

Yeh-lii Yiian's assumption of the throne by hereditary right as the eldest

son of A-pao-chi's eldest son roused the opposition of the still-formidable

empress dowager Ying-t'ien. She supported the claim of her own favorite

third son Li-hu, the younger brother of the deceased emperor. His claim was

not groundless, for in 930 T'ai-tsung had appointed him heir apparent or,

according to some sources, as the imperial great younger brother (huang t'ai

ti).

Once again there was a conflict between the Chinese style of hereditary

succession and the Khitan tribal custom of succession by brothers. The

empress sent Li-hu with an army to block Yiian's return to the capital. When

Li-hu's army was defeated, the redoubtable old lady led her own army to

confront the new emperor. On the Shira muren, just south of the Supreme

Capital, the two armies faced each other for several days.

The crisis was resolved by the mediation of a royal cousin named Yeh-lii

Wu-chih (916-72). This time the empress dowager was unable to have her

way. Wu-chih and the Khitan nobles rejected Li-hu on the grounds that he

had made himself generally hated because of his cruelty. The empress dowa-

ger gave in, telling Li-hu that he had brought failure on

himself.

21

21 LS, 77, pp. 1255—6. An interesting source regarding these events is the account written by Hu

Chiao, a Chinese official of the Chin who had been taken back on the retreat from K'ai-feng in Hsiao

Han's entourage. After the latter's execution for his part in a plot in 949, Hu fled east and then

eventually back to China in 953. His account is cited in Ou-yang Hsiu, Hsin Wu-tai shib, 73, pp.

904—8;

Ma Tuan-lin,

Wen

hsien t'ung k'ao, in Sbih t'ung (Shanghai, 1936), 345, pp. 2704c—5c. For a

translation, see F.douard Chavannes, "Voyageurs Chinois chez les Khitan et les Joutchen," pt. 1,

Journal Aiiatiqut, 9th series, no. 9 (1897), pp. 390—411.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

-]6 THE LIAO

The confrontation between the legitimate hereditary heir and the late

emperor's brother was thus resolved in favor of

the

hereditary heir. But it was

not his hereditary claim that had prevailed; rather, his rival had been rejected

by the nobility because he was personally unacceptable as a ruler. Although

the empress lost, the Khitan principle of "electing" a suitable candidate was

what swayed the decision. Moreover, opposition to the new emperor, whose

posthumous temple name is Shih-tsung (r. 947—51), remained powerful.

Much of his short reign was spent dealing with dissidence among the royal

family and nobility.

Both the empress dowager and Li-hu were banished from court and sent to

live in retirement at Tsu-chou, the Khitan ancestral cult center. (The empress

outlived Shih-tsung and died in 953, aged seventy-four.) If the new emperor

hoped that this would secure his position, he was soon disillusioned. The

internal situation in the Liao remained unstable.

In 948 a plot against the emperor's life was organized by T'ien-te, the

second son of T'ai-tsung. The conspiracy failed, and T'ien-te was executed.

Although the other conspirators were punished, their lives were spared.

Among them was Hsiao Han, a nephew of the empress dowager who was

married to the new emperor's sister, A-pu-li. The next year he was involved

in another plot with some dissident nobles. Again, even though he was

proved guilty, the emperor tried to hush up the matter and released him.

Finally in 949 a letter was intercepted in which Hsiao Han was plotting

another uprising, this time with An-tuan, one of A-pao-chi's surviving

brothers. This time Shih-tsung had had enough; Hsiao Han was executed and

the princess died in prison.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS

Shih-tsung was not entirely preoccupied with this constant round of in-

trigue. During his brief reign there were some important institutional

changes. They were not entirely innovations but, rather, the culmination of

changes that had been taking place gradually for many years. It is difficult to

follow the development of Liao government institutions. The Liao shib"

provides a detailed, if often confusing, picture of the mature government

system as it existed in the early eleventh century, but few clues to the stages

by which various offices and bureaus came into being and almost nothing

about how they intermeshed to form a working system of administration.

Shih-tsung's reign was clearly a crucial time. Ever since the acquisition of the

sixteen Chinese prefectures in 938, it had been necessary to establish more

22 LS, 45-8, pp. 685-831.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE DEVELOPMENT OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS 77

and more sophisticated government institutions to control the millions of

new Chinese subjects. The temporary occupation of north China brought a

huge number of former Chinese officials into the Liao system and with them

came a tendency to adopt many of the techniques of Chinese administration.

The most striking feature of Liao administration was the dual system of

government that had been gradually emerging for many years. Since early in

the tenth century, it had been customary to divide offices into "northern" and

"southern." The imperial clan itself had a southern division, made up of A-pao-

chi's close relatives of the Six Divisions, and a northern division comprising

more distant relatives. A-pao-chi had appointed northern and southern prime

ministers

{pei-fu

tsai-hsiang, nan-fu tsai-hsiang). The nature of this system was

symbolized in a decree of T'ai-tsung's later years that ordered that the offi-

cials of the Northern Administration and the empress dowager

—

the arch-

representative of the old tribal ways - wear Khitan costume and that the

officials of the Southern Administration and the emperor himself dress in

Chinese style.

2

' This northern and southern division of government was not a

strictly geographical one; the "Northern Administration" was responsible for

the Khitan and tribal peoples, wherever they lived, and the "Southern Ad-

ministration" was responsible for the Chinese population, as had been the

Chinese Office (Han-erh ssu) that A-pao-chi had set up in his early years.

At the beginning of Shih-tsung's reign, immediately after his return to the

Supreme Capital, he formally divided the empire into Northern and Southern

Regions (Pei-mien, Nan-mien). These were true regional divisions of Liao

territory. The Southern Region comprised the predominantly Chinese and

Po-hai areas of the south and east. The Northern Region was the area largely

settled by Khitan and dependent tribal peoples. Because the Northern Re-

gion also included stable settlements of Chinese, Po-hai, and even Uighurs,

it was given a dual administrative system. It had therefore both a Khitan

Northern Commission for Military Affairs (Ch'i-tan Pei shu-mi yiian) and a

Khitan Southern Commission for Military Affairs (Ch'i-tan Nan shu-mi

yiian).

The southern commissioners were usually members of the Yeh-lii royal

clan, the northern commissioners mostly members of the Hsiao consort clan.

The administration of the Northern Region was mainly, though not exclu-

sively, staffed by Khitan holding traditional Khitan titles. Its most powerful

officers were the Khitan commissioners for military affairs, the prime minis-

ters of the Northern and Southern administrations

{Pei-fu

tsai-hsiang, Nan-fu

tsai-hsiang),

the Northern and Southern Great Kings

{Pei

Ta-wang, Nan Ta-

wang),

both of whom were members of the royal clan, and the commander in

chief {yu-yueh). These men controlled all military and tribal affairs, the

23 LS, 56, p. 908.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

78 THE LIAO

selection of military commanders, the disposition of the tribal herds, and the

allocation of pastures. Beneath them was a bewildering array of tribal offi-

cials,

an office for the royal clan of the former Po-hai state, and a range of

offices providing services to the imperial house: artisans, physicians, hunts-

men, and commissioners responsible for the royal herds, stud farms, and

stables. No one could possibly confuse the administration of the Northern

Region with the orderly model of T'ang government. It was essentially a

great tribal leader's personal retinue, and many of its offices were specifically

reserved for members of one or another branch of the royal or consort clans

and filled by hereditary selection

(shih-hsiian).

The government of the Southern Region was more of

a

deliberate creation

than that of the Northern Region, which had evolved from traditional

Khitan institutions. It came into being after 948, when Shih-tsung returned

to the capital following the capture of K'ai-feng and the transportation to the

Khitan capital of great numbers of Chinese officials. It was modeled closely

on the government institutions of T'ang and the Five Dynasties. The Khitan

had used many Chinese titles earlier than this, both before and after the

assimilation of the sixteen border prefectures in 937. But it is unclear how far

these titles had implied the existence of Chinese-style bureaus with any

regular

staff.

In many cases they were clearly honorific titles, the Khitan

emperors following the old-established practice of the T'ang court in confer-

ring ranks and honorary offices with no real duties, as a reward for loyal

services.

In 947, however, the Khitan had at last created a Chinese-style dynasty,

with all the outward trappings of a Chinese court. The government of the

Southern Region was designed in imitation of

a

T'ang model. It was based,

as was the government of the Northern Region, at the Supreme Capital,

where it had its main offices. It had the traditional groups of elder states-

men, the Three Preceptors

(san shih)

and the Three Dukes

(san kung)

to act as

imperial advisers, and a complex bureaucracy at the head of which were three

ministries similar to the three central ministries

(san sheng)

of early T'ang.

There was a Chinese Commission for Military Affairs (Han-jen Shu-mi

yiian),

which combined the functions of the Commission for Military Affairs

(Shu-mi yiian) under the Five Dynasties with those of the T'ang Department

of State Affairs (Shang-shu sheng) and controlled five rather than six execu-

tive boards; a Secretariat (at first called Cheng-shih sheng; after 1044,

Chung-shu sheng) headed by a grand prime minister (ta

ch'eng-hsiang)

and

two deputy prime ministers

(ch'eng-hsiang)

and including a staff of secretaries

and councillors; and a Chancellery (Men-hsia sheng) responsible for drafting

documents. Each of these ministries had, on paper at least, a complicated

bureaucratic establishment similar to its T'ang model, but only the Secretar-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE DEVELOPMENT OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS 79

iat played any significant role in political decisions. There was also the

Censorate (Yii-shih t'ai), the Han-lin Academy, the Office of Historiogra-

phy, and various groups of court scholars, all organized along Tang lines.

There was an imperial household department, various specialized courts

(ssu)

and directorates

(chieri),

a formal establishment for the heir apparent, and a

military organization of royal guards

{wet).

The basic provincial organization also began to take shape along Chinese

lines.

Beside the Supreme Capital there was now an Eastern Capital at Liao-

yang, controlling former territories of Po-hai, and a Southern Capital at

modern Peking, controlling the former Chinese territories acquired in 937.

A fourth Central Capital was to be added in 1007, built on the site of

the

old

Hsi capital, at the time when the Hsi were finally assimilated into the

Khitan state. Last, a Western Capital at Ta-t'ung was established in 1044.

Each of

these

capitals was not so much an alternative seat of imperial govern-

ment (as, e.g., Ch'ang-an and Lo-yang had been in early T'ang) as the

regional center of a circuit, a local administrative network. Each of these

circuits seems to have followed administrative procedures appropriate to its

own population. The picture was further complicated during the tenth cen-

tury by the fact that two of the larger groups of conquered peoples, the Hsi

and Po-hai, retained a great degree of autonomy under their own leaders and

paid tribute as vassals rather than taxes as subjects. Only in the early eleventh

century were these populations fully incorporated into the Liao system of

government.

The viceroys

(liu-hou)

of these capitals wielded great power over their

circuits, especially those of the Southern and Eastern capitals, who were

among the most powerful men in the Liao system of government. They

presided over a hierarchy of numerous prefectures and counties that provided

the field administration for the settled regions of the empire and that in

many areas coexisted with tribal organizations ruled on traditional lines.

The system of government in the Southern Region was similar, at least in

its outward forms, to that of the T'ang and the Five Dynasties. Many of its

officials, especially at the lower and middle levels, were ethnic Chinese.

Historians familiar with Chinese institutions of

the

ninth and tenth centuries

may, however, be tempted to ascribe an unreal importance to the holders of

titles which, in the Chinese system, implied great power and influence.

There was one important distinction, however, between the officers of the

Northern and Southern regions, apart from their different racial origins. Liao

emperors were constantly on the move and resided in their Supreme Capital

only for short periods each year as they traveled from one traditional seasonal

hunting camp

(na-po)

to the next. Twice a year, in the fifth and tenth lunar

months, the officers of both the Northern and Southern administrations were

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

80 THE LIAO

summoned to the emperor's camp for deliberations on state affairs. In winter

the officers of the Southern Administration went south to the Central Capital

to mediate the affairs of the Chinese subjects of the Southern Region. But for

most of the year, as the emperor's great retinue progressed around the north-

ern territories, making contact with the leaders of the tribal world, the

emperor was still expected personally to make all the important decisions

affecting the state and to mete out justice. On these peregrinations he was

accompanied by most of the great officers of the Northern Administration,

who lived with him on close personal terms, as much his companions (like

the

nokor

of Mongol times) as his great officers of state. By contrast, only a

handful of officials from the Southern Administration - a single prime minis-

ter and a small group of secretaries and drafting officials

—

formed a part of

his regular entourage. Clearly the officials of the Northern Administration,

by virtue of their constant access to the emperor, enjoyed far greater real

power than did those of the Southern Administration.

Thus the Southern Administration was essentially an executive organiza-

tion for the southern areas and their settled population. The high-sounding

titles of its officers should not conceal the fact that routine decision making

and all military authority (southern officials were specifically excluded from

decisions on military affairs at court) were concentrated in the emperor's

Khitan entourage drawn from the Northern Administration.

Moreover, we should not be too influenced by the official structure de-

scribed in the Liao history. Many of the offices seem to have been filled only

sporadically. Power in the Khitan world, in spite of the bureaucratization

that began in Shih-tsung's time and continued in fits and starts into the

eleventh century, had little connection with a formal and orderly government

structure. It remained to the end far more dependent on an individual's

personal qualities and his achievements, on his family connections, his per-

sonal relationship with the emperor and powerful ministers, his friendships,

and his military following. Powerful personalities and brute force still far

overshadowed institutional niceties in the Khitan world.

RELATION WITH REGIMES IN CHINA

Under Shih-tsung, the Liao, in spite of their withdrawal from K'ai-feng,

remained embroiled in the turbulent politics of northern China. In 948 the

Southern T'ang renewed their attempt to form an alliance with the Khitan

against their northern neighbors, this time the new northern regime of the

Han. They were rebuffed. In the winter of 949-50 Shih-tsung launched a

large-scale raid into Hopei, attacking several cities well inside the Han

border and taking many captives and much booty. The Southern T'ang court

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008