Teodorescu P.P. Mechanical Systems, Classical Models Volume II: Mechanics of Discrete and Continuous Systems

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

16 Other Considerations on the Dynamics of the Rigid Solid

We can calculate the angle of nutation as a function of

t, making, after F. Klein,

0

uu v=+,

[

]

0,2vu∈ , in the polynomial ()Qu given by (16.1.12). We find thus

() ()

02220

00 0 0

33

() 2 1 4 1Qu av u u uv v u avωε ε ε ω=−−+−−

⎡⎤

⎣⎦

,

where we have neglected the higher-order powers of

v, which is of the order of

magnitude of

ε; taking into account (16.1.13) and neglecting the higher-order powers

(the product

vε with respect to ε or to v), it results

()

2

0

3

() (2 )Qu a v u vω=−.

(16.1.14)

The formula (16.1.11') allows to calculate

()

()

0

30

0

d

arccos

2

v

uv

att

u

u

ξ

ω

ξξ

−

−= =

−

∫

,

wherefrom

()

[

]

0

30

1cosvu a ttω=− −

; the relation

()

00

00 00

cos cos 2 sin sin sin

22

vuu

θθ θθ

θθ θθθ

−+

=− = − =− ≅− −

gives the angle of free nutation in the form

()

[]

0

00

3

0

() 1 cos

sin

u

tattθθ ω

θ

=− − −

()

[]

0

0

00

3

0

3

sin 2

1cos

2

att

a

θ

θε ω

ω

=− − −

,

(16.1.15)

by means of the relation (16.1.13). Hence, the variation of the angle of nutation

θ is

periodical, with the period

()

()

00 0

3333

2/ 2/ / 2/

E

aJITπ ω πω πω=<=,

0

3

ω being

the angular velocity in the diurnal rotation of the Earth (which is acceptable in the

frame of the above approximation); hence, the period of variation of the nutation angle

is a little smaller than a sidereal day (

305/ 306 of

E

T

).

The angle of precession is given by the first relation (15.2.2) in the form

()

02

3

cos / sinaψαω θ θ=−

; taking into account (16.1.15), neglecting the higher

order powers of

ε and noting that

0

cos cos vθθ=+

0

cos θ=

()

00

sinθθ θ−− , we

can write (we use the same method as above)

()

[]

()

[]

0

3

00

00 0

33

2

0

1 cos cos 1 cos

sin

au

att att

ω

ψωεθω

θ

=−−−=−−−

too. By integration, one obtains the angle of pseudoregular precession (we put the initial

condition

00

()tψψ= )

393

() ()

[]

00

000 0

33

0

3

() cos sintattatt

a

ε

ψψ θω ω

ω

=− −− − ,

(16.1.16)

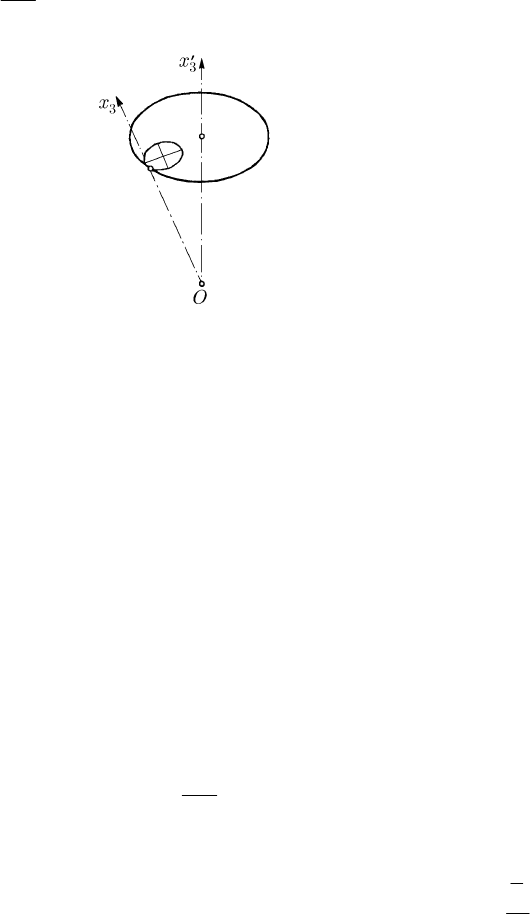

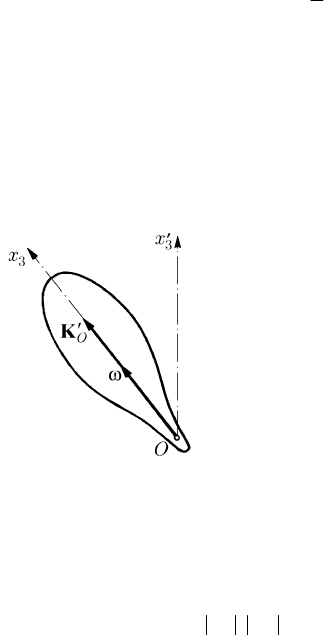

Fig. 16.4 The elliptic cone described by the

3

Ox -axis in the motion of the Earth

which – unlike the regular precession – is a non-linear function of time. Thus, besides

the motion of regular precession on the cone of vertex angle

0

2θ

, intervenes a

supplementary motion given by the additive terms in the formulae (16.1.15), (16.1.16);

hence, the

3

Ox

-axis describes also an elliptic cone (Fig. 16.4) of extreme vertex angles

()

0

0

3

/cosaεω θ and

()

0

0

3

/sin2aεω θ about axes specified by the angle of precession

()

00

costtεθ−− and by the angle of nutation

()

0

00

3

/2 sin2aθεω θ− , respectively.

The ratio of the extreme vertex angles is equal to

0

2 sin 2 sin 23 27 0.7959θ

′

=≅

D

;

hence, the elliptic cone described by the

3

Ox -axis is, approximately, a circular cone

(the ratio of the axes is approximately equal to

0.8), the period of rotation being equal

to

()

0

3

2 / 305/306

E

aTπω= , hence somewhat smaller than a sidereal day.

The third equation (15.2.2) leads to

0

3

cosϕω ψ θ=−

; proceeding as in the case of

the precession angle and neglecting afterwards

2

ε with respect to ε , we obtain

()

[

]

002

00

33

1cos cosattϕω ε ω θ=+ − − , wherefrom

()

() ()

02 2 0

00000

33

0

3

() cos cos sintttatt

a

ε

ϕϕωεθ θω

ω

=+ + −− −,

(16.1.17)

with the condition

00

()tϕϕ= .

Once Euler’s angles determined, we can calculate the components

j

ω and

j

ω ,

1, 2, 3j =

, of the angular velocity vector ω in the frames of reference R and R ,

obtaining then the equations of the polhodic and of the herpolhodic cone, respectively.

16.1.2.4 Other Considerations

To obtain a much more correct image of the motions of the Earth, one must take into

account also the periodic terms in the perturbing forces due to the Sun, Moon etc.; one

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

394

16 Other Considerations on the Dynamics of the Rigid Solid

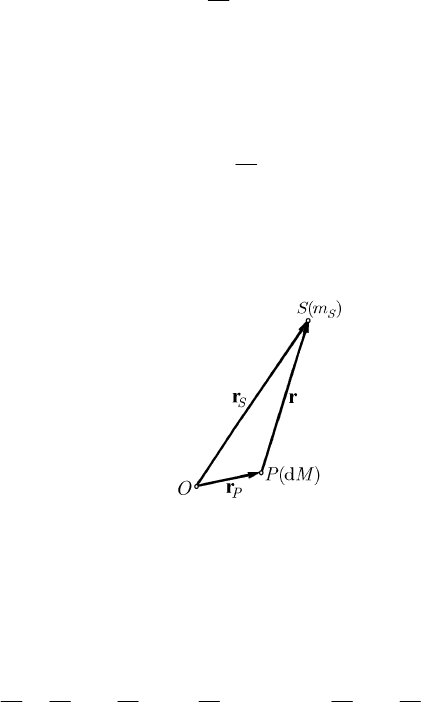

can no more assume that the mass of the Sun, e.g., is uniformly distributed along its

trajectory. Modelling the Sun as a particle of mass

S

m we can calculate the moment

O

M in the form

3

1

d

OS P

M

f

mM

r

=×

∫

Mrr,

(16.1.18)

where

P

r is the position vector of a particle P of the Earth, of mass dM (M is the mass

of the Earth), while

PS=

J

JJG

r , S being the mass centre of the Sun (Fig. 16.5); in this case

3

1

d

j

Oi S ijk k

M

Mfm xM

r

ξ=∈

∫

,

(16.1.18')

where

j

x are the co-ordinates of the point P, while

k

ξ are the co-ordinates of the point

S, ,1,2,3jk= , with respect to the frame of reference R.

Fig. 16.5 The influence of perturbing terms in the motion of the Earth

Noting that the dimensions of the Earth are small with respect to the distances

r and

S

r (

SP

=−rr r), we can expand the ratio 1/r into a series after the powers of the

ratios

/

i

S

xr,

1, 2, 3i =

; neglecting the higher-order powers, it results

3/2

33 2 2 3 2

11 2 1 1 3

11

ii ii ii

SS S SS

xxx x

rr r r r r

ξξ

−

⎛⎞⎛⎞

=− + ≅+

⎜⎟⎜⎟

⎝⎠⎝⎠

.

Taking into account that

O is the centre of the terrestrial oblate spheroid, we can make

considerations analogous to those in Sect. 16.1.1.3, so that

d0

i

M

xM=

∫

, d0

j

k

M

xx M=

∫

, jk≠ , ,, 1,2,3ijk= ,

() ()

22 22

13 23

dd

MM

xxM xxM−=−

∫∫

() ()

22 22

12 23 3

dd

MM

xxM xxMIJ=+ −+ =−

∫∫

.

395

It results

()

323

1

5

3

S

O

S

m

MfIJxx

r

=−

,

()

313

2

5

3

S

O

S

m

MfIJxx

r

=− −

,

3

0

O

M = .

(16.1.18'')

Euler’s equations (16.1.1) read

123

12

3

O

SS

S

M

xx

n

n

Jrr

r

ωω

′

+= =

,

213

21

3

O

SS

S

M

xx

n

n

Jrr

r

ωω

′

−= =−

,

3

3

0

0

IJ

n

J

ω

−

=>,

3

30

S

IJ

nfm

J

−

′

=>

.

(16.1.19)

These equations may be expressed also by means of Euler’s angles and of other angles

which specify the position of the Sun with respect to the frame of reference

R.

However, neither the results thus obtained do not coincide with those given by the

astronomic observations, because of the model of rigid solid assumed for the Earth. In

reality, the Earth is a deformable solid or, more correct, a mechanical system formed by

solid and fluid parts; some of them can be even rigid. In the hypothesis of rigid of the

Earth, its central ellipsoid of inertia being an oblate spheroid, it results that the rotation

angular velocity about the axis of the poles is constant; but if we take into account a

modelling of the Earth much closer to the reality, one sees that this velocity is varying,

resulting difficult problems for the determination of the unit of time (specified by the

diurnal rotation of the Earth).

A heavy rigid solid with a fixed point

O for which the ellipsoid of inertia corresponding

to this point is of rotation about the principal axis of inertia

3

Ox (

12

IIJ==), its

initial motion being a rapid motion about this axis, is called gyroscope. After some

general results, we present various applications with theoretical or technical character.

We make firstly some general considerations concerning the motion of regular

precession of the gyroscope, assuming to be in the Euler-Poisson case; as well, we put

in evidence the gyroscopic effect which appears if the gyroscope is acted upon by its

own weight or by an arbitrary force. We introduce then the gyroscopic moment and the

gyroscopic reactions, calculating also the inertial forces which arise in the motion of

regular precession of the gyroscope.

If the moment with respect to the fixed point

O, corresponding to all the given external

forces which act upon the gyroscope, vanishes (

O

=M0), then we are in the Euler-

Poinsot case; we can thus use all the results given in Sect. 15.1.

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

16.2 Theory of the Gyroscope

16.2.1 General Results

16.2.1.1 The Euler-Poinsot Case. Stability of the Motion

396

16 Other Considerations on the Dynamics of the Rigid Solid

If we wish that the symmetry axis of the gyroscope, which is a symmetry axis of the

motion too, maintains its direction, then we must have

=ωω and

′

=

0ω ,

corresponding to the decomposition (15.2.14) in Sect. 15.2.1.4; we equate thus to zero

the motion of regular precession. The formula (15.2.17') shows that this property of the

motion takes place if

O

=M0, hence in the considered Euler-Poinsot case (Fig. 16.6).

Hence, a gyroscope to which it was imparted a motion about its axis of symmetry

maintains unchanged the direction of this axis if the moment of all the external forces

with respect to the fixed point vanishes. In the case in which the gyroscope is acted

upon only by its own weight, we fulfill this condition choosing the centre of gravity as

fixed point.

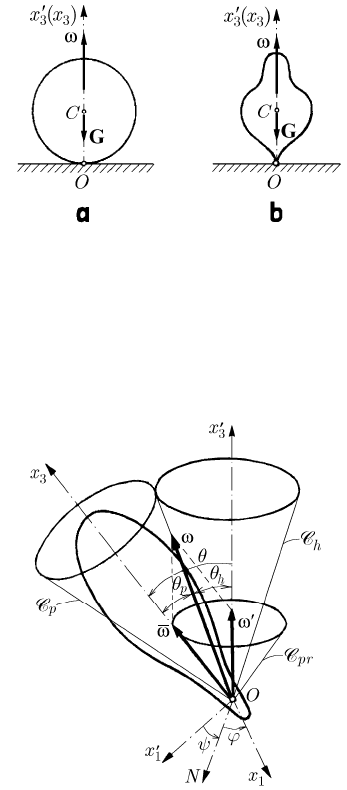

Fig. 16.6 The gyroscope for which the motion of regular precession is equated to zero

As it has been shown in Sect. 15.1.2.7, the symmetry axis of the gyroscope, which is

also an extreme principal axis of inertia, is stable during the motion. Indeed, let us

suppose that an arbitrary perturbation imparts to the vector

ω a direction somewhat

different from

3

Ox , having the components

12

,0ωω≠ ; these components verify the

equations (16.1.2), being of the form (16.1.2'), so that

0

12

,ωω ω≤ ,

0

ω arbitrary.

We can state that the stability of the axis is as greater as the period

2/Tnπ= (n

given by (16.1.2)) is smaller, hence as the proper velocity of rotation of the gyroscope

is greater. As well, we notice that the stability increases as the moment of inertia

3

I is

greater than the moment of inertia

J (the ellipsoid of inertia corresponding to the fixed

point is a very oblate spheroid).

In all these cases, the moment of momentum

O

′

K is directed along the

3

Ox

-axis so

that

3

O

KIω

′

= .

One can thus explain a great number of mechanical phenomena: (i) The knife

thrower throws the knife upwards with one hand and catches it with the other hand; to

do this, he gives to the knife a motion of rotation about its axis, before throwing it, the

axis maintaining thus its direction during the motion. (ii) When he jumps from a certain

height, the skier rotates both arms stretched laterally in the same sense, about the same

horizontal line; in this case, the skier remains in a vertical position, so that he is falling

on his feet. (iii) A body with an axis of symmetry becomes a motion of rotation about

this axis, in a horizontal position, by means of a thread between two rods, being then

thrown upwards; the axis remains horizontal during the motion and the body can be

397

easily caught on the thread from which it was thrown. This is the diabolo game. (iv) A

coin with a vertical diameter or a top with a vertical axis of symmetry

3

Ox , staying on

a horizontal plane, can maintain for some time the position of its axis if it becomes a

motion of rotation about the respective axis

33

Ox Ox

′

≡ (Fig. 16.7); the interval of time

is as greater as the rotation angular velocity is greater. (v) The disc of Gervat’s

gyroscope has the horizontal axis maintained in labile equilibrium on one foot (the

“equilibrist foot”), formed by a thin metallic tube; giving to the disc a sufficiently rapid

motion of rotation, the gyroscope remains in equilibrium.

Fig. 16.7 A coin (a) or a top (b) maintains the position of its axis for some time

16.2.1.2 General Considerations on the Motion of Rotation of the Gyroscope

In general, the moment of the given external forces with respect to the fixed point

O is

non-zero (

O

≠M0). If the gyroscope is acted upon only by its own weight, then we

are in the Lagrange-Poisson case, so that one can use the results in Sect. 15.2.1.

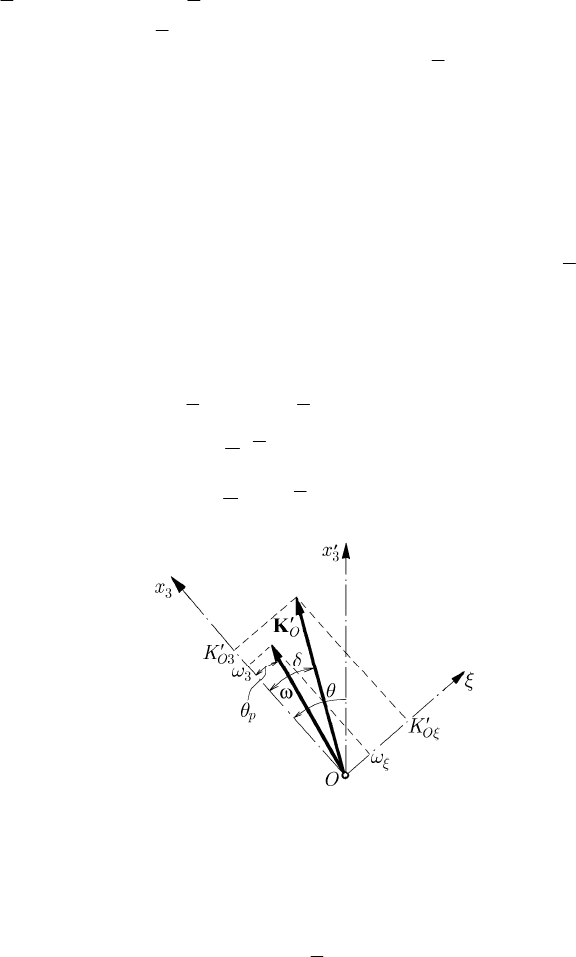

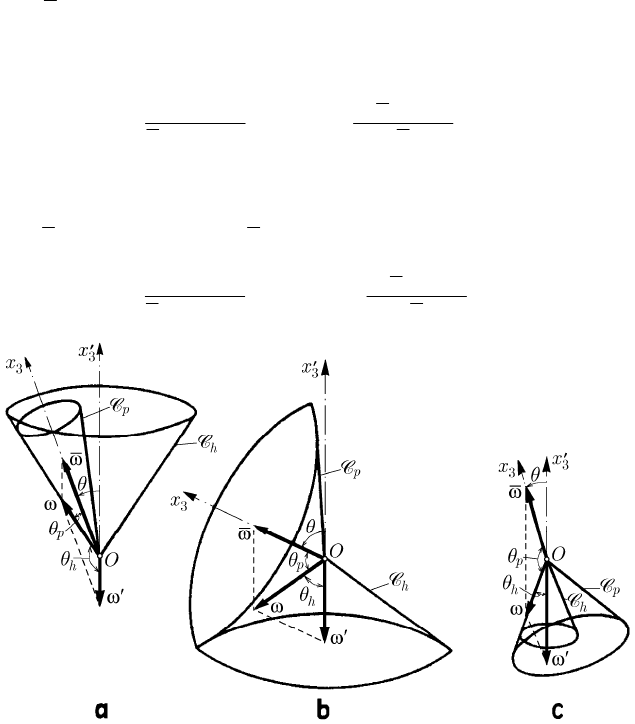

Fig. 16.8 The cone of precession

pr

C in the motion of rotation of the gyroscope

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

398

16 Other Considerations on the Dynamics of the Rigid Solid

Decomposing the rotation angular velocity vector

ω along the fixed

3

Ox

′

-axis, along

the movable

3

Ox -axis and along the line of nodes ON, respectively, we can write

33

ωω θ

′′

=+ +

iin

ω

with ωϕ= , ωψ

′

=

. Assuming that

0θ =

, hence constθ = ,

it results that the vector

ω describes the cone of precession

pr

C with the

3

Ox

′

-axis and

of vertex angle

2θ (Fig. 16.8). Further, we suppose that constω = and constω

′

= ;

in this case, we have

constω = too, the angles

h

θ and

p

θ made by the vector ω with

the

3

Ox

′

-axis and the

3

Ox -axis, respectively, being also constant. We notice that

p

h

θθ θ+= too. In this case, the vector ω will describe the herpolhodic cone

h

C of

axis

3

Ox

′

and vertex angle 2

h

θ , with respect to the frame of reference

′

R

, and the

polhodic cone

p

C of axis

3

Ox and vertex angle 2

p

θ , with respect to the frame R,

respectively. The motion of rotation of the gyroscope will be thus composed by a

uniform proper rotation of angle

ϕ and a proper rotation angular velocity ω , about the

3

Ox -axis and a motion of regular precession of angle ψ and angular velocity of

precession

ω

′

about the

3

Ox

′

-axis (Fig. 16.8). By decomposing the vector ω, one

obtains easily the relations

22

2

2cosωωω ωωθ

′′

=+ +

,

()

1

cos cos

P

θωωθ

ω

′

=+ ,

()

1

cos cos

h

θωωθ

ω

′

=+ .

(16.2.1)

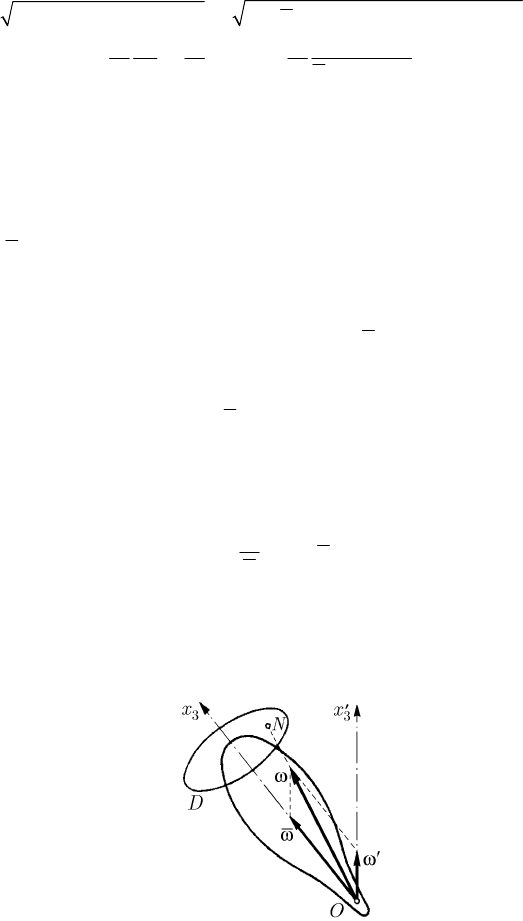

Fig. 16.9 The components of the vectors ω and

O

′

K

in the motion

of rotation of the gyroscope

Let be the

Oξ -axis normal to

3

Ox , in the

33

Ox x

′

-plane. The components of the

vectors

ω and

O

′

K will be (Fig. 16.9)

3

cos cos

p

ωωθωω θ

′

==+,

sin sin

p

ξ

ωωθωθ

′

==,

33

3

O

KIω

′

= ,

O

KJ

ξξ

ω

′

= .

399

It results

()

2

22 22 2 222

33

cos sin cos sin

pp

O

KI J I Jωθ θ ωωθωθ

′′′

=+=++,

33 3 3

sin

tan tan

cos

p

JJ J

II I

ξ

ω

ωθ

δθ

ωωωθ

′

== =

′

+

,

(16.2.2)

where

δ is the angle made by the moment of momentum

O

′

K with the

3

Ox -axis. This

vector is situated in the

33

Ox x

′

-p1ane, hence it is rotating together with this plane about

the fixed axis

3

Ox

′

with the angular velocity

′

ω

; this vector describes, as well, a cone of

axis

3

Ox

′

and vertex angle

()

2 θδ−

(we notice that constδ = too).

If

/1ωω

′

, then we can assume, that 0δ ≅ , the moment of momentum

O

′

K

being directed, with a good approximation, along the

3

Ox -axis; hence,

333

O

IIω

′

==Kiω . Noting that, in this case, the velocity of the extremity of the

vector

O

′

K is given by

3

OO

I

′′′ ′

=× = ×

KKωωω, we find again the formula

(15.2.17") which gives the moment

O

M . In a scalar form, we can write

3

sin

O

MIωω θ

′

= ,

(16.2.3)

in the limits of the hypothesis made. In general, we will have

()

sin

OO

MKωθδ

′′

=−,

wherefrom

()

33

cos sin

O

MIJI

ω

θωω θ

ω

′

⎡⎤

′

=−−

⎢⎥

⎣⎦

,

(16.2.3')

corresponding to the formula (15.2.17'). In particular, if

/2θπ= , hence if

33

Ox Ox

′

⊥ , then we find again the formula (16.2.3), which is now an exact formula.

Fig. 16.10 Pohl’s experiment

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

400

16 Other Considerations on the Dynamics of the Rigid Solid

To put in evidence the motion – described above – of the gyroscope, we can make –

together with Pohl – a simple experiment. We fix on the gyroscope axis a disc

D on

which we have put a printed paper (e.g., from a journal) (Fig. 16.10). During the

rotation of the gyroscope, one cannot distinguish the letters (one can see only a uniform

gray), excepting the piercing point N of the support of the vector ω, on the disc D (the

velocity vanishes at the point

N, so that the letters in the vicinity of this point are

practically at rest and can be read). Pohl says that “the axis of rotation and the axis of

the gyroscope rotate one around the other, as a pair of dancers”.

If

/0ωω

′

> (the positive sense of the components of the vector ω is the positive

sense of the co-ordinate axes

3

Ox

′

and

3

Ox respectively, hence if 0/2θπ≤< , then

we obtain

sin

tan

cos

p

ωθ

θ

ωω θ

′

=

′

+

,

sin

tan

cos

h

ωθ

θ

ωω θ

=

′

+

,

(16.2.4)

from (16.2.1). The cones

p

C and

h

C are exterior (as in Fig. 16.8); the motion of

precession is progressive and the general motion of the gyroscope is epicycloidal.

If

/0ωω

′

< , then we have

()

, πθ

′

=−) ωω too, so that

p

h

θθ πθ+=−, while

sin

tan

cos

p

ωθ

θ

ωω θ

′

=−

′

+

,

sin

tan

cos

h

ωθ

θ

ωω θ

=−

′

+

.

(16.2.4')

Fig. 16.11 The motion of the gyroscope: hypocycloidal (a),

inverse epicycloidal (b) and inverse hypocycloidal (c)

In this case, the motion of precession is retrograde. We notice that

/2ππθπ<−<,

hence

0/2 /2πθπ<−<. If /2

h

θπ> , then it results /2

p

θπ< and tan 0

p

θ > ,

401

tan 0

h

θ < , so that cos / 0θωω

′

−< <, the cone

p

C being interior to the cone

h

C

(Fig. 16.11a); the motion of the gyroscope is hypocycloidal. If

/2

p

θπ< and

/2

h

θπ< , then one can show that tan 0

p

θ > and that tan 0

h

θ > , so that

1/cos / cosθωω θ

′

−<<−, the cone

p

C being exterior to the cone

h

C

(Fig. 16.11b); the motion of the gyroscope is inverse epicycloidal. If

/2

p

θπ> , then it

results

/2

h

θπ< and tan 0

p

θ < , tan 0

h

θ > , so that /1/cosωω θ

′

<− , the cone

h

C being interior to the cone

p

C (Fig. 16.11c); the motion of the gyroscope is inverse

hypocycloidal (pericycloidal).

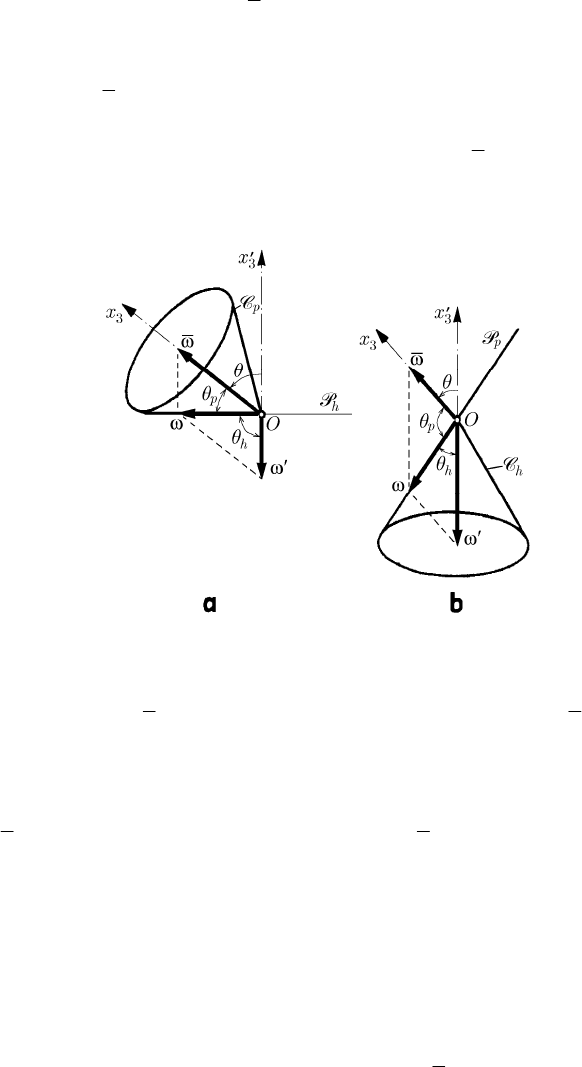

Fig. 16.12 The motion of the gyroscope: the cone

p

C

is rolling slidingless over the fixed

plane

h

P (a); the plane

p

P is rolling slidingless over the fixed cone

h

C (b)

The limit case

/0ωω

′

= has been considered in Sect. 16.2.1.1. If /cosωω θ

′

=− ,

then

/2

h

θπ= (the component

′

ω

is normal to the vector ω), while the cone

h

C is

reduced to the plane

h

P , which passes through the vector ω, being normal to

3

Ox

′

(Fig. 16.12a); the cone

p

C is rolling without sliding over the fixed plane

h

P . If

/1/cosωω θ

′

=− , then /2

p

θπ= (the component ω is normal to the vector ω),

while the cone

p

C is reduced to the plane

p

P , which passes through the vector ω,

being normal to

3

Ox (Fig. 16.12b); this plane is rolling slidingless over the fixed cone

h

C .

Let be a gyroscope fixed at its centre of gravity

C (OC≡ ) and subjected to the

action of its own weight

G (the Euler-Poinsot case); we assume that to this gyroscope is

imparted an initial rotation angular velocity

0

ω , which makes an angle

p

θ with the

3

Ox -axis of the gyroscope (Fig. 16.13). If the fixed axis is

3

Ox

′

and

()

33

,Ox Oxθ

′

= ) , then we can write

()

/sin /sin /sin

pp

ωθω θθ ω θ

′

=−=

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

402