Telo M. European Union and New Regionalism. Regional Actors and Global Governance in a Post-Hegemonic Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

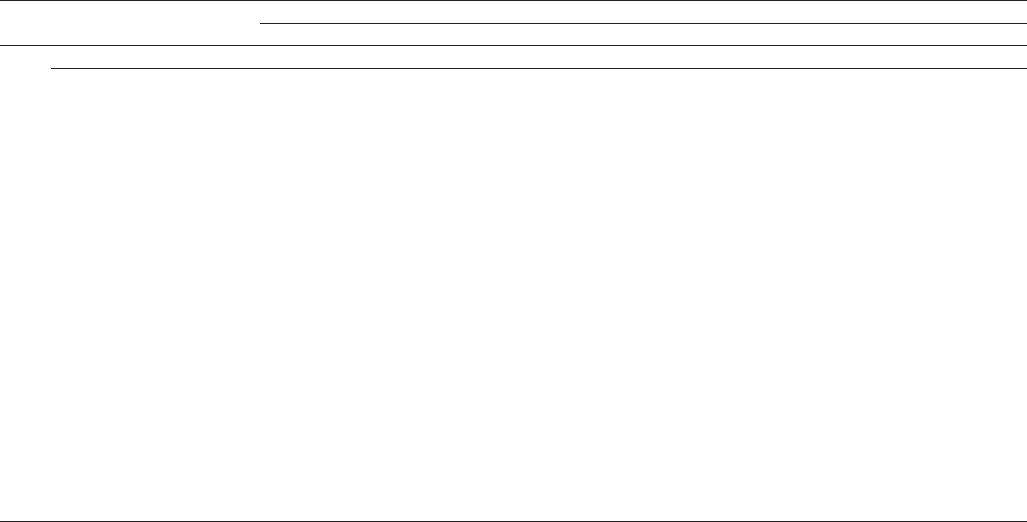

Value ($USm) Growth (%) Share (%) by region

1995 2000 2004 95/00 00/04 1995 2000 2004

EXPORT

Asia 9171 7971 17537 -13 120 13 9 13

European Union 18012 20025 30078 11 50 26 24 22

Intra MERCOSUR 14451 17741 17114 23 -4 21 21 13

USA 10773 16930 24678 57 46 15 20 18

Rest of the World 18087 22196 44453 23 100 26 26 33

World 70493 84863 133861 20 58

IMPORT

Asia 7920 10085 15029 27 49 10 11 16

European Union 21949 21069 20007 -4 -5 27 24 21

Intra MERCOSUR 14439 17713 17879 23 1 18 20 19

USA 17635 18693 15696 6 -16 22 21 17

Rest of the World 17915 20882 26210 17 26 22 24 28

World 79 858 88 441 94 821 11 7

Total Trade

Asia 17091 18055 32566 6 80 11 10 14

European Union 39961 41094 50086 3 22 27 24 22

Intra MERCOSUR 28890 35453 34994 23 -1 19 20 15

USA 28407 35623 40374 25 13 19 21 18

Rest of the World 36001 43078 70663 20 64 24 25 31

World 150 351 173 304 228682 15 32

Source: Trade SIA of the Association Agreement under negotiation between the European Community and Mercosur, Update on the Overall

Preliminary Trade SIA EU-Mercosur and Sectoral Trade SIA’s. Inception Report, September 2006

Table 8.1 MERCOSUR main trading partners

European Union and MERCOSUR

169

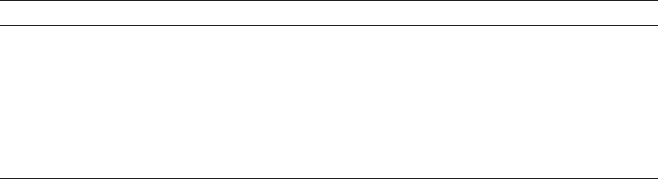

Although the trade agreement between the EU and MERCOSUR never happened,

and although Brazil developed an internationally active commercial policy,

particularly aimed at Asia and Africa, Europe continued to be MERCOSUR’s

main trade partner, absorbing 22.5% of its exports, and also its main provider

(21.1% of MERCOSUR imports). MERCOSUR exports for the EU in 2004

measured in terms of value are more than twenty times greater than imports.

The non-fruition of the free trade agreement with MERCOSUR, as well as

the signing of free trade agreements with Chile and Mexico, resulted in a decline

in favour of those two partners, from 1995 to 2004, of MERCOSUR’s share as a

recipient of EU exports from 50% to 36%.

2.1 Integration and democratization

MERCOSUR most resembles the European model in the need felt by the states of

South America at the end of the 1980s to consolidate their democratic structures,

and in the process to overhaul the security concepts espoused by the military

regimes throughout the years of dictatorship. According to Helio Jaguaribe, this

amounted to establishing a distinction between internal and external security, and

preventing the ‘army from being induced into interference in the state’s internal

affairs, instead becoming converted to protectors of the civil authority’.

11

As in

Europe after the Second World War, a post-sovereign political culture emerged in

the newly democratic states, particularly in the academic and industrial spheres

– a development made possible only by the liberation of external and internal

policy alike from the geopolitical concepts adopted by the military. The success of

MERCOSUR has contributed greatly to the consolidation of this new democratic

orientation.

The reconciliation between Brazil and Argentina, made possible by the

political transition in these two countries led by Presidents Sarney and Alfonsin,

was perceived as being an underlying condition for democratic consolidation.

The Treaty of Integration, Cooperation and Development signed by Brazil and

Table 8.2 Trade flows between EU and MERCOSUR (measured in

thousands of euros)

YEAR EU imports from MERCOSUR EU exports to MERCOSUR

1999 9 191 944 866 242

2000 10 574 162 980 777

2001 12 040 351 840 914

2002 12 182 517 638 612

2003 12 296 726 590 788

2004 13 537 979 582 381

Source: Trade SIA of the Association Agreement under negotiation between the European

Community and Mercosur, Update on the Overall Preliminary Trade SIA EU-Mercosur

and Sectoral Trade SIA’s. Inception Report, September 2006

European Union and New Regionalism

170

Argentina in 1988 established a focus on the objectives of democratization and

development, though not yet at this stage on international competitiveness. The two

countries have changed the strategic culture that had hitherto marked their bilateral

dealings, and which had seen both countries pursuing aggressive nuclear armament

programmes. Those programmes have been abandoned, and the neighbours have

stopped regarding each other as enemies.

For Argentina and Brazil, the change in bilateral relations was fundamental

in gaining international legitimacy for their fledgling democracies. The creation

of MERCOSUR extended this process to Uruguay and Paraguay, traditionally

the buffer states between the ‘big two’ of the Southern Cone. The establishment

through this means of international recognition and credibility was seen as a way

of underwriting democracy, and thus represented a convergence of international

interests among the four countries

12

MERCOSUR was thus born from the

democratization of the countries of the region, and is based on the twin principles

that the success of regional integration depends on the democratic nature of the

regimes involved, and that the consolidation of democracy depends – at least in

part – on the progress of integration. As José Luis Simon has argued, ‘If democratic

politics and integration are intricately linked in the MERCOSUR, this is all the

more true for Paraguay, for which integration is much more than mere trade; indeed,

the MERCOSUR created the conditions for the implementation of democracy in

Paraguay’.

13

Democracy is undoubtedly the founding principle of MERCOSUR, and the

founder governments are fully aware of this, as was apparent from their concerted

response to General Oviedo’s attempted coup d’état in Paraguay in April 1996.

The members made it clear that it was unacceptable for one state in the group to

jeopardize the democratic legitimacy of the whole. Shortly after this episode, the

fragility of democracy in Paraguay had prompted the MERCOSUR countries to

introduce a democracy clause into the constitutional arrangements of the group.

The presidential declaration of Potrero de los Funes (in June 1996) not only stated

that ‘all change to the democratic order constitutes an unacceptable obstacle

for the continuation of the democratic process in progress’, but made provision

for sanctions, ranging from suspension to expulsion from MERCOSUR, to be

applied to any country jeopardizing democracy. Following this declaration, the

MERCOSUR states have included the principle of political conditionality in their

agreements with other countries. Moreover, on 24 July 1998 the democracy clause

was extended with the Protocol of Ushuaia to include Chile and Bolivia, countries

with which MERCOSUR has association agreements. It is interesting to note that

in the EU context a similar democracy clause was introduced only in June 1997,

in the Treaty of Amsterdam, in view of the envisaged expansion of the Union to

Central and Eastern Europe.

MERCOSUR, in fact, represents the coming together of two projects: one

political, defined by the democratic commitment of the participating countries and

lacking any hard structure or well-defined contours; the other economic, aimed

at liberalization and commercial openness, both among the member states and

towards the outside world. MERCOSUR can thus be described as an ‘open pole’

model within the international system.

14

By the end of the 1990s, MERCOSUR

European Union and MERCOSUR

171

was a success, a ‘trade mark’ as the Brazilian President then described it, which has

undoubtedly given its member states a new credibility.

MERCOSUR and the EU embody essentially the same model of regionalism,

namely that of ‘open integration’. Not only do MERCOSUR and the EU both set

the condition that a state must be democratic in order to join; both project through

their external relations, especially with their neighbours, the fundamental values

that legitimate their own integration processes. Clearly the EU cannot base its

international action upon an essentially Hobbesian idea; this reductive view is

neither accepted nor understood by its citizens, who consider that its legitimacy

resides in its democratic nature. This assumption has been a component of the

European Community ever since its creation – in contrast to EFTA, one of whose

founder members was Portugal under Salazar. It was for this reason that neither

Portugal nor Spain could initially join the EC; conversely, as soon as the two

countries had jettisoned their authoritarian regimes, both considered accession to

the Community a fundamental requirement for the consolidation of democracy

at home. Due to the nature of Hugo Chavez’s regime, Venezuela’s joining

MERCOSUR on 4 July 2006 caused a degree of anxiety regarding the strength

of MERCOSUR’s democratic clause, and its international identity. Nevertheless,

Venezuela’s integration is a process whereby the new member country must accept

all of MERCOSUR’s conditions, namely concerning the Customs Union, a process

that will not be completed until 2014. This timeframe must be employed to reaffirm

the democratic clause. The international legitimacy of the integration process itself

will largely depend on MERCOSUR’s ability to ensure Venezuela’s respect for

human rights and for democratic legality, and by the way the country will react if

and when the latter are infringed.

Since their transition to democracy, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay

and have all attached great importance in their foreign policies to democracy and

human rights issues. This commitment was demonstrated by all four MERCOSUR

members in their declaration of support for the constitution of the International

Criminal Court in Rome, in July 1998. However, the controversy over the fate of the

former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet has divided the MERCOSUR countries

on the potential conflict between the safeguarding of fundamental rights, on the

one hand, and state sovereignty on the other. Their past experience of dictatorship

has influenced the four countries in different ways. With problems similar to those

faced by Chile – of military political crimes committed during the dictatorship and

not yet brought to court – Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay echoed the Chilean

government’s protest at what they called Britain’s and Spain’s interference in the

domestic affairs of Chile. Brazil took a less critical approach. The opposition of

the MERCOSUR countries, and indeed of Latin America in general, to the element

of extraterritoriality in US policy towards them was made clear in the common

declaration on the Pinochet affair made by MERCOSUR, Chile and Bolivia, in

which they denounced the ‘unilateral and extraterritorial application of national

laws, violating the juridical equality of nations and the principles of respect and

dignity of the sovereignty of states and of non-intervention in domestic affairs,

and threatening their relationships’. At the same time, however, the signatories to

the document ‘recognize and encourage the gradual development of international

legislation dealing with the penal responsibility of a person guilty of committing

European Union and New Regionalism

172

international crimes’. MERCOSUR’s member states have maintained this

perspective of defending multilateral solutions, and of a huge mistrust towards

the concepts of extraterritoriality – an attitude which has been reinforced by the

unilateralism of George W. Bush’s administration.

2.2 Institutional shortcomings

A fundamental difference between the EU and MERCOSUR relates to the

latter’s institutional shortcomings. Up to now, MERCOSUR has been a purely

intergovernmental body, with decisions taken unanimously in the absence of

any form of supranational institution. This situation is a result of the sovereignty

concept which still dominates diplomacy in the region, and of Brazil’s opposition

to any system that might place it in the minority. In the EU, by contrast, there exists

a complex system of weights and counterweights – the weighted votes system,

the provision for blocking minorities, qualified majority voting, a parliament

with real (albeit limited) powers – to help balance power across participating

states and protect them from excessively strong leadership by any member or

members. MERCOSUR’s lack of institutions means a lack of any check on strong

leadership, and the consensus rule provides only a limited constraint.

15

In Europe,

the France–Germany axis is part of a system of multiple and shifting alliances; in

MERCOSUR, the Brazil–Argentine axis is the unchanging core. This asymmetry

among the countries involved will continue and the enlargement to Venezuela didn’t

change this. The asymmetry has become more pronounced in the past few years,

with the impact of the Argentine crisis. Brazil’s relative weight in the equation

will tend to increase with the passing of time. The resolution of MERCOSUR’s

institutional asymmetry remains a deciding factor for the future of the Southern

Cone’s integration project, a process which must not continue to depend on the

kindness, or ‘strategic patience’, of Brazil, as Celso Lafer has called it.

16

On this

issue President Cardoso remarked in 1998 that ‘Brazil must take up this challenge.

We are going to have to improve the institutionalization of MERCOSUR’.

17

In recent years there has been talk of setting up a tribunal to handle commercial

disputes, and this would undoubtedly be an important step. Lately, however, and

somewhat against the grain, a decision was taken in 2004 to create the Parliament of

MERCOSUR. Essentially, this new institution aims to promote an approximation

of its citizens to the integration process, and its members are elected by direct and

universal suffrage in each of the member states. With apparently limited powers,

it should nevertheless be noted that one of the goals of this new institution is the

preservation of democratic regimes in the member states, in accordance with

MERCOSUR’s norms, in particular with the Ushuaia Protocol on Commitment to

Democracy in MERCOSUR, the Republic of Bolivia and the Republic of Chile.

The MERCOSUR Parliament must compile an annual report about the human

rights conditions in all member states.

European Union and MERCOSUR

173

3 Crises of the turn of the century

In 1996, 25 per cent of all Argentinean exports and 14 per cent of Brazil’s were

destined for MERCOSUR countries; the corresponding figures for 1990, before

MERCOSUR was established, were 16.5 per cent and 7 per cent respectively. The

change has been less marked for Paraguay and Uruguay, for whom Argentina and

Brazil were already the leading trade partners. The credibility of MERCOSUR

was demonstrated by the significant annual rise in the volume of international

investments, up from US$1,284 million in 1991 to US$8,925 million in 1996.

The financial crisis of the late 1990s that first faced Brazil, and later and

more seriously Argentina, represented a great challenge for MERCOSUR, with

Argentina coming out of the crisis in a much weaker position than Brazil. The

Argentine government implemented some tough measures to try and abate the

crisis, and the IMF gave Argentina more than $20 billion in emergency aid. But

the international help was not enough, however, and by the end of 2001, Argentina

verged on economic collapse. This crisis also had serious implications for Uruguay

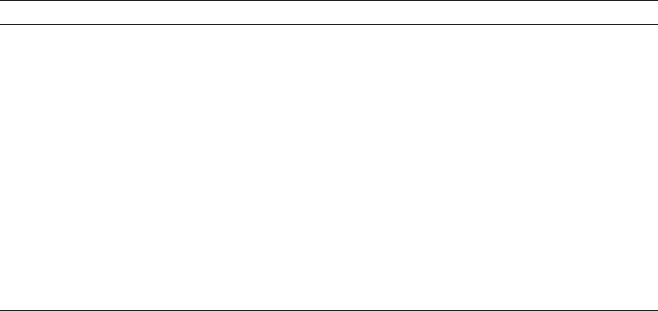

and Paraguay. The crises were followed by political change in both Brazil and

Argentina, and this had a powerful impact on the trade relations between the two

countries, which from 2004 onwards, from the traditional pattern in favor Argentina,

an asymmetric imbalance favours Brazil.

The crises at the turn of the century were followed by political change both

in Brazil and Argentina. This created a set of dynamics in the region, whereby

internal issues became the basic priority for leaders like Lula, such as the social

agenda and the fight against poverty. MERCOSUR remained an important priority

of the Brazilian government, but now in the context of a more diverse regional

and international agenda. The idea of building a South American Community of

Nations, initiated back in the government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, became

a core objective of the Lula Administration, and the group obtained its name at

Table 8.3 Trade relations between Brazil and Argentina *

Year Exports Imports

1995 4,023,310 5,748,338

1996 5,164,560 7,131,037

1997 6,761,631 8,287,234

1998 6,743,503 8,420,599

1999 5,358,729 6,110,115

2000 6,226,243 7,197,801

2001 4,995,338 6,533,356

2002 2,337,537 5,019,893

2003 4,557,500 4,949,514

2004 7,370,704 5,904,801

2005 9,911,807 6,591,043

2006 8,621,905 4,494,535

* thousands of dollars

Source: ALADI – Estadísticas de comercio exterior

European Union and New Regionalism

174

the Cuzco Summit in Peru, in December 2004. The Community is still a poorly

defined project and has not as yet approved a founding treaty. This South American

priority is quite clear in the enlargement of MERCOSUR to Venezuela, a move that

was considered necessary by Brazilian diplomacy, in order not to isolate Chavez,

and as an attempt to water down the tension between Chavez and the American

administration.

But with Venezuela joining, the need to define the MERCOSUR’s international

identity becomes more evident. Some may be tempted to respond affirmatively to

Felix Peña’s question: is MERCOSUR a political project in which economic and

commercial concerns remain subordinate to more generic objectives – such as a South

American identity – which for some of its members could signify an affirmation

of interests in direct opposition to those of the United States?

18

It is certainly from

a perspective of South American nationalism that Chavez sees Venezuela’s entry.

The Lula administration’s position is, however, a good deal more complex. If the

South American project has attained a new level of priority, it does not signify the

affirmation of an anti-United States project. For Brazil, the South American project

is integrated, as is MERCOSUR, in its affirmation as an emerging global power

and as an important platform, with a view to achieving international integration

under more favourable conditions, and to negotiate under more advantageous

ones with the United States. There is an apparent contradiction, however, in

Brazil’s desire for international affirmation as a global power and MERCOSUR’s

political consolidation, precisely due to the existing asymmetries and the lack of

cooperative mechanisms in the realm of foreign policy. This was made apparent

in Brazil’s campaign for permanent membership of the United Nations Security

Council without managing to develop a common platform with its MERCOSUR

partners, particularly Argentina. Even the priority Brazil has awarded the South

American project is seen by some as a risk of weakening the commitments already

made within MERCOSUR, in the process of establishing of a wider cooperative

space – a space whose practical effects are somewhat less potent.

19

According to

the Lula administration’s perspective, there is no contradiction in the project of a

South American Community of Nations and the deepening of MERCOSUR, which

should function as its hard core.

20

What MERCOSUR does demonstrate, however,

is the difficulty in progressing with a deep integration project without a serious

effort towards the harmonization of foreign policies. But even where international

trade is concerned, deep rifts are emerging among the members of MERCOSUR

during the whole Doha Round process, with Brazil bringing together the Group

of Twenty to face the European Union and the United States, but with Uruguay

actively opposing this strategy. The rifts between MERCOSUR member states are

equally evident in other areas, as demonstrated by the so-called ‘paper mill crisis’

between Argentina and Uruguay. This situation not only shows the current level

of disagreement between member states, but also clearly reveals the inability on

behalf of MERCOSUR’s institutions to provide a platform for resolving differences

between member states. For all the above reasons, MERCOSUR appears weaker

now than at the end of the twentieth century.

European Union and MERCOSUR

175

4 The United States and MERCOSUR

The Clinton government, in line with the orientation of the Bush I administration

at the end of the 1980s,

21

has given priority to free trade agreements as a structural

element of the dominant US position in world trade – and as a vehicle for the

world-wide dissemination of American interests and values. ‘The trade agreements

of the post-Cold War era will be equivalent to the security pacts of the Cold War

– binding nations together in a virtuous circle of mutual prosperity and providing

the new front line of defence against instability. A more integrated and more

prosperous world will be a more peaceful world – a world more hospitable to

American interests and ideals’.

22

The American strategy in the 1990s was to promote global regionalization with

the United States as the hub of the world, by means of large-scale agreements

such as the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas), APEC or the proposed

Transatlantic Marketplace with the European Union (see the planisphere 3 at the

end of this volume). However, in so doing it sometimes ran into opposition from

powerful isolationist sectors of American society, and from the labour unions, such

as AFL-CIO.

23

Some influential political figures favour a more isolationist stance,

believing it (perhaps rightly so) to be closer to the instincts and preferences of most

Americans. It is this political sensitivity that caused Congress to deny President

Clinton the ‘fast track’ option that would have enabled him to negotiate free trade

agreements directly, particularly with Latin American countries.

24

The George W.

Bush administration didn’t change the American approach towards regionalization

drastically, namely in relation to Latin America and Asia, but it awarded it a

priority so low that there has been no United States dependent real progress in this

process.

For the United States, MERCOSUR remains a trading detour, an optional step

in the regionalization of the Americas. Many US politicians see Brazil as the Latin

American country that is most independent of US foreign policy, and the only

real opponent of the US position on the free trade area. Some even take the view

that MERCOSUR, working towards a strong relationship with the EU, is part of

a Brazilian strategy of independence, and that Brazil is setting itself up as a kind

of Latin American France. Argentina, by contrast, has been more closely aligned

with US international security policy. Unlike Brazil, Argentina has participated

in military operations led by the United States, such as the ‘Desert Storm’

campaign during the Gulf War in 1991; and, by way of thanks for this support,

President Clinton has granted Argentina the status of leading ally outside NATO,

a rank already bestowed on Israel, Egypt, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and

Jordan.

The Brazilian opposition to the FTAA became the official policy of the Lula

government in line with the position defended by the eminent Brazilian sociologist

Helio Jaguaribe, going so far as to assert that MERCOSUR must say no to the

FTAA because ‘constitution of the FTAA implies, in practice, the disappearance of

MERCOSUR as it would lead to the elimination of customs frontiers between all

the countries of America and, as a result, of the common external tariff, which is

one of the fundamental characteristics of MERCOSUR’.

25

European Union and New Regionalism

176

The project of FTAA due to the opposition of Brazil and the low priority given

to it by the George W. Bush administration was replaced by a number of bilateral

agreements between the US and several Latin American countries, namely those

on the Pacific coast such as Chile (2003) and Peru (2006). Some member of

MERCOSUR are tempted by the signing of bilateral trade treaties with the United

Sates, namely Uruguay and Paraguay, but even Argentina signed with the United

States a ‘Bilateral Council on Trade and Investment’, in 2002. Bilateralism is

prevailing over the logic of block negotiations, even though one of MERCOSUR’s

principal factors was its affirmation as a Customs Union, bargaining as one voice

with the United States and Europe.

5 MERCOSUR as a strategic partner of the EU

Despite its limited international influence, MERCOSUR is a strategic partner for

the EU in building a new multilateralism based upon a more balanced relationship

with the United States. This view is strong in Portugal, Spain and Italy for

historical reasons, and in Germany because of its large investments in the countries

of the region. For many European countries, MERCOSUR’s importance lies only

in the part it plays in their foreign trade. If Europe were only a trading region,

then MERCOSUR would be reduced to a ‘backyard’ of the United States, in a

version of the Monroe Doctrine by which South America was prevented from

engaging in political dialogue with partners other than the United States.

26

But

even from a strictly economic viewpoint, it would be a mistake to overlook the

importance of MERCOSUR for the EU – which is amply demonstrated by the fact

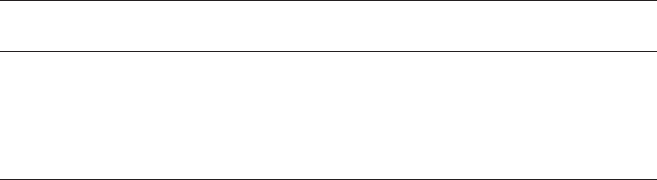

that EU member states are the principal investors in the region, with Brazil being

the main destination of the European FDI. In 2003, the FDI stock of the EU in

Brazil amounted to US$ 47,997 million and to US$ 23,193 million in Argentina.

Traditional investors such as France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Italy

and Germany, were joined by Spain (the EU member with the largest stock of FDI

in MERCOSUR), and Portugal.

A fresh boost was given to relations with Latin America when Portugal and

Spain joined the European Community in 1986. Indeed, a declaration about those

relations was annexed to the membership treaty. This impetus was reinforced

on the Latin American side by the successful consolidation of democracy in the

region and by the appearance of regional groups – the Andean Community and

the Central American Community, as well as MERCOSUR itself. The European

Commission, under the influence of Portugal and Spain, has attempted to promote

relations with these groups and with Mexico, taking advantage of Mexico’s role

as a member of NAFTA and of the Iberian countries’ turns to preside over the

Council of Ministers. It was in 1992, during the Portuguese presidency, that the

first informal ministerial meeting took place between the twelve members of

the European Community and the four members of MERCOSUR; and it was

in 1995, during the Spanish presidency of the Union, that the EU-MERCOSUR

framework agreement and the project for an interregional free trade area were

launched.

European Union and MERCOSUR

177

In the following decade, the consolidation of the Free Trade agreement did

not take place, and only almost ten years later, in 2004, did negotiations make

significant progress. However, they did so while coming up against the ever-present

agricultural and service sector difficulties, as well as the priority awarded by

MERCOSUR member states to the attempt to obtain more significant concessions

from the World Trade Organization.

Both MERCOSUR and the EU look upon free trade and globalization differently

from the United States, which sees these processes in complete accordance with

its own interests. For the EU and MERCOSUR the continental and global free

trade projects, accompanied by the deregulation, may jeopardize cohesion among

member states and lead to a loss of identity conferred by projects that go beyond

the establishment of free trade arrangements, whether in the shape of a customs

union (as in MERCOSUR), or in the more ambitious form of an economic and

monetary union (in the EU), especially regarding the social model on which these

groupings are based. However, the EU and MERCOSUR have not been able to

give substance to this relation through a trade agreement .In the 1990s Europe

was not able to correspond to MERCOSUR’s demand of opening its markets for

agricultural trade from the MERCOSUR countries. In the first years of the twenty-

first century it was the MERCOSUR countries, Brazil in particular, who resisted

such an agreement, emphasizing the Doha Round’s potential to free up trade to their

advantage. The failure of the Doha Round has perhaps created renewed conditions

for the relaunching of the ten-year-old EU-MERCOSUR project for a free trade

agreement.

Table 8.4 Foreign Direct Investment flows to MERCOSUR

1991-1995 ** 1996-2000** 2001-2005**

$USm (% Total) $USm (% Total) $USm (% Total)

Argentina 3,781.5 58 11,516.1 31 2,980.6 15

Brazil 2,477.4 38 24,823.6 68 16,480.7 83

Paraguay 103.8 2 185.1 1 53.9 0

Uruguay 82.5 1 187.2 1 367.9 2

MERCOSUR 6,445.2 36,757.1 19,883.1