Tabak J. Beyond Geometry: A New Mathematics of Space and Form

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

30 BEYOND GEOMETRY

bit wordy because good algebraic notation had not been invented

yet, but in modern notation he noticed that he could define a func-

tion on the natural numbers according to the following formula:

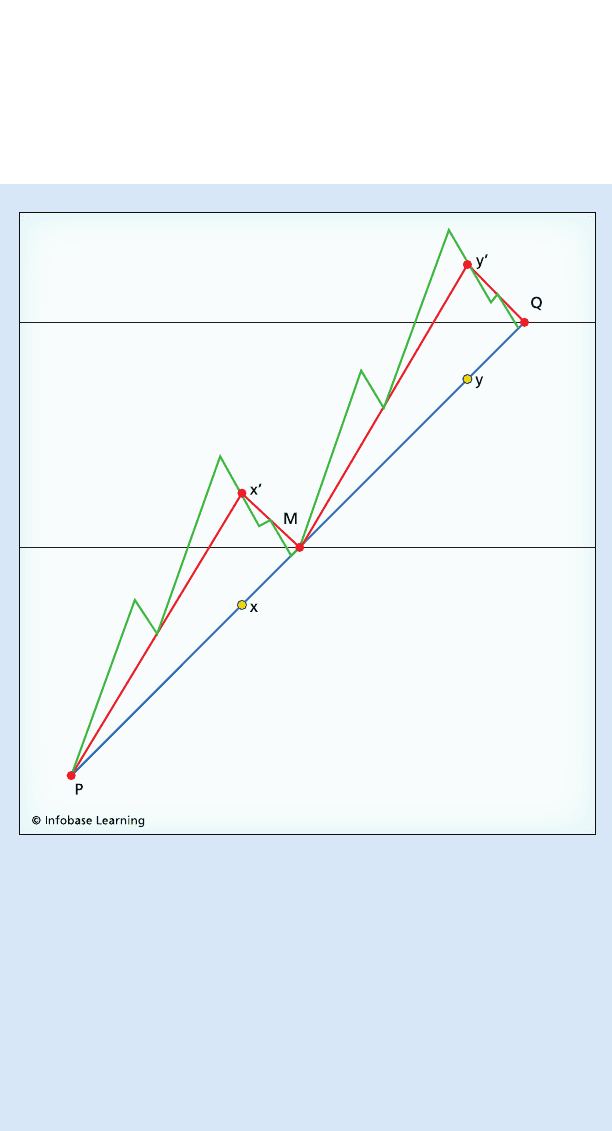

counterexample 2: a continuous

nowhere differentiable function

The 18th-century belief that the points at which a function fails to have a

derivative are isolated from one another—and in that sense, “exceptional”—

is false. The first counterexample was produced by Bolzano. Here is his

method for producing a curve that is continuous at each point but fails to

have a derivative at any of its points. His counterexample dates to 1830.

Step 1: Draw a nonhorizontal line segment PQ and label the

midpoint of the segment M.

Step 2: Draw a horizontal line though M, and draw a second

horizontal line through Q. Find the point on the segment PM

that is three-fourths the distance from P to M, and label it x.

Find the point on the segment MQ that is three-fourths the

distance from M to Q, and label it y.

Step 3: Reflect the point x about the horizontal line passing

through M. Label this new point x′. Reflect the point y about the

horizontal line passing through Q, and label this new point y′.

Step 4: Using straight line segments, connect P to x′ and con-

nect x′ to M. Similarly, use straight line segments to connect M

to y′ and y′ to Q. The result is a graph with four straight seg-

ments and three corners.

Now repeat steps 1 through 4 on each of the resulting segments.

Continue to repeat steps 1 through 4 on each of the resulting seg-

ments to produce a graph with an ever-increasing number of corners.

This produces a sequence of graphs of functions. The formulas for the

functions in this sequence are not especially difficult to find, but the formu-

las are long and not especially informative. Instead of deriving the formulas,

label the first function f

1

. This is the straight line segment with which we

began. Label the second function f

2

. This function has the red graph. It rep-

resents the result at the end of step 4. If we repeat the procedure on each

segment of the red graph, we get the green one. Call the function with this

graph f

3

. By continuing in this way, we obtain a sequence of such functions

f

1

, f

2

, f

3

, . . . The further one goes in the sequence, the more closely spaced

the corners are placed on each graph. Now imagine vertical parallel lines.

A Failure of Intuition 31

f(n) = n

2

. His function paired each natural number n with a perfect

square n

2

: The number 1 is paired with 1; the number 2 is paired

with 4; the number 3 is paired with 9; and, in general, the number

No matter how close the lines are placed to one another, all functions with

a large enough subscript will have at least one corner somewhere between

those vertical lines. The sequence of functions described in the algorithm

determines a “limit function” that has corners everywhere. (The proof of this

last statement is too difficult to produce here.)

Bolzano’s procedure begins with the straight (blue) line. The red line is

obtained at the completion of step 4 of the procedure. The green line is

obtained after applying steps 1–4 to each of the straight segments that

make up the red line. Repeat again and again. The resulting graph

converges to one that is continuous and nowhere differentiable.

32 BEYOND GEOMETRY

n is paired with n

2

. As Galileo pointed out, it might seem that

there are far fewer perfect squares than natural numbers because

the percentage of perfect squares in the set consisting of the first n

natural numbers approaches zero as n becomes large, but because

the set of natural numbers is infinite, a one-to-one correspondence

can still be established.

Although he was careful to document his “paradoxical” results,

Bolzano never used them to develop a clear understanding of the

real number system. A clear conception of the real number system

did not develop until the latter part of the 19th century, when

mathematicians learned how to manipulate infinite sets. A deeper

understanding of infinite sets enabled them to obtain a new and

deeper understanding of mathematics in general. The mathema-

tician most responsible for establishing the theory of sets is also

generally credited with founding the modern era in mathematics.

His work also marks the introduction of general topology, which

he helped to create in order to overcome some of the problems

described so far in this narrative.

33

3

a new mathematical

landscape

During the latter half of the 19th century, modern mathematics

began to take shape. The geometric constructions of Leibniz and

Newton—a visual language that had proven to be inadequate to

describe subsequent discoveries—were finally replaced by a more

abstract language founded on the theory of sets.

At first glance, sets are about as primitive a concept as can be

imagined. The concept of a set, which is, after all, a collection

of objects, might not appear to be a rich enough idea to support

modern mathematics, but just the opposite proved to be true. The

more that mathematicians studied sets, the more astonished they

were at what they discovered, and astonished is the right word. The

results that these mathematicians obtained were often contro-

versial because they violated many common sense notions about

equality and dimension. Some mathematicians were left by the

wayside complaining about mathematical “absurdities.” The more

adaptable ones changed their notions of what constituted “com-

mon sense notions.” Georg Cantor, who did more than anyone

else in establishing the theory of sets, is said to have exclaimed

about one particularly remarkable proof of his own making, “I see

it but I don’t believe it!”

As these mathematicians learned more, they began to impose

additional structure on their sets. They began to distinguish

among infinite sets of different sizes and different (topological)

properties. Their research revealed an entirely new mathematical

landscape full of exotic mathematical objects, but more than the

answers they obtained, their research raised new questions. Ideas

34 BEYOND GEOMETRY

as basic to science and mathematics as that of dimension were

called into question. One of the accomplishments of set-theoretic

topologists is that their discoveries helped to restore order to

mathematics by identifying (or creating, depending on one’s point

of view) underlying patterns, the existence of which no one had

previously suspected.

Richard Dedekind and the Continuum

The German mathematician Richard Dedekind (1831–1916)

made an essential step in arithmetizing analysis by making explicit

the relationship between real numbers and the real number line.

The ancient Greeks had assumed that a line is a continuum of

points. They also assumed that, in contrast to the line, numbers

did not form a continuum. These two ideas, the continuity of lines

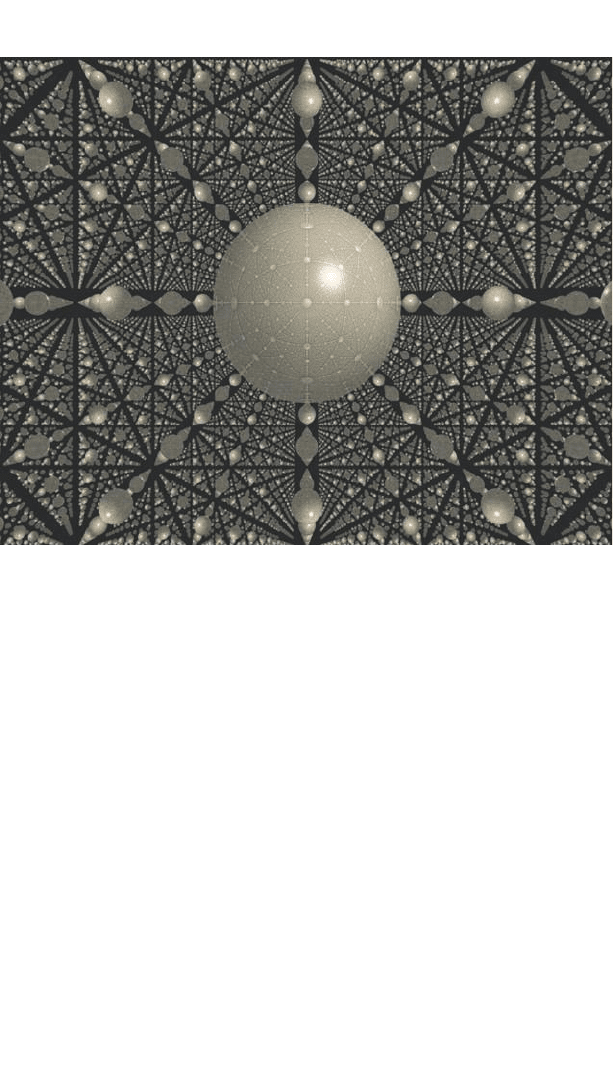

Some of the logical implications of the concept of infinity strike many people

as strange, even today. Part of what it means to learn mathematics is

becoming accustomed to the strangeness of the infinite.

(Casey Uhrig)

A New Mathematical Landscape 35

and the discrete nature of numbers, were accepted by mathemati-

cians for the next 2,000 years. In his famous paper “Continuity and

Irrational Numbers,” Dedekind questioned both ideas. He wrote

that the belief that the line forms a continuum was an assump-

tion—one could not prove this statement—but if the line were

continuous, so was the set of all real numbers. His conception of

the real number line continues to influence mathematics on an

elementary and advanced level today.

Dedekind studied mathematics at Göttingen University under

Carl Friedrich Gauss, one of the leading mathematicians of the

19th century. For seven years, he taught at the university level,

first at Göttingen and later at Zurich Polytechnic. For the next 50

years, he taught in Braunschweig, Germany, at the Technical High

School, a remarkable choice for one of the most forward-thinking

mathematicians of his age.

Since the time of the Greeks, irrational numbers had remained

something of a puzzle. Recall that rational numbers are numbers

that can be represented as the quotient of two whole numbers.

The numbers ½ and ¾, for example, are rational numbers, but

the number √2 is not rational because there is no choice of whole

numbers, a and b, such that their quotient, a/b, when squared,

equals 2. The number √2 is, therefore, an example of an irrational

number. More generally, the set of irrational numbers is defined

to be the set of numbers that are not rational.

Nevertheless, to defined something by what it is not yields very

little information about what it is. The definition of irrational

numbers as not rational goes back to the Greeks, who considered

geometry and arithmetic to be very separate subjects, in part

because geometry (as they understood it) dealt with continuously

varying magnitudes—lines, surfaces, and volumes, for example—

and arithmetic was concerned with numbers, which they regarded

as discrete entities, but to do analysis rigorously, mathematicians

needed a continuum of numbers. In other words, they needed as

many numbers as there are points on a line. Dedekind established

a one-to-one correspondence between the points on a line and the set

of real numbers. He demonstrated that he could “pair up” points

and numbers in the following one-to-one way: Each number was

36 BEYOND GEOMETRY

paired with exactly one point on the line, and each point on the

line was paired with exactly one number. Through his correspon-

dence, Dedekind demonstrated that the set of all real numbers

forms a continuum provided one was willing to accept the con-

tinuity of the real line. (To be clear about the concept of one-to-

one correspondence, imagine an auditorium in which everyone

is seated. If every chair is taken, then there are as many people

as chairs in the auditorium. If some of the chairs are empty, then

there are more chairs than people. We may not know how many

people or chairs are in the auditorium, but the concept of one-to-

one correspondence still enables us to draw conclusions about the

relative sizes of the set of people in the auditorium and the set of

chairs in the auditorium.)

In Dedekind’s model of the real number system, the rational

numbers play a special role. These numbers can be placed into

one-to-one correspondence with a subset of points on the real

line. To see how, begin with a line. Identify one point on the line as

zero, and identify a second point (to the right of zero) as the num-

ber one. Now measure off distances on the line corresponding to

the natural numbers. They are located to the right of zero and are

multiples of the zero-one distance. Once the points correspond-

ing to the natural numbers have been located, use them to iden-

tify points corresponding to the rational numbers. (Any rational

number can be expressed in terms of sums, differences, products,

and quotients of natural numbers.) Positive rational numbers cor-

respond to distances to the right of zero; negative rational num-

bers correspond to distances to the left of zero. We will call the

points corresponding to these rational distances “rational points.”

However, this procedure leaves numerous “gaps” in the line. It

does not, for example, generate a point corresponding to √2 or a

point corresponding to the number π, because neither of these is

a rational number. The question Dedekind sought to answer is,

“What is the nature of these gaps?”

Dedekind expressed his answer in terms of cuts of the real line,

now famously called Dedekind cuts. Each cut identifies a unique

point, which is the location of the cut, and every point determines

a unique cut. His method shows that there exist as many numbers

A New Mathematical Landscape 37

as cuts. In particular, he shows that the set of all real numbers

forms a continuum. Mathematicians now call this property “com-

pleteness,” but Dedekind wrote that his construction demonstrat-

ed that the domain of real numbers “. . . had the same continuity as

the straight line.”

To establish Dedekind’s correspondence imagine making a cut

at a point P, where P is some arbitrarily chosen point on the line.

The point P divides the set of rational points into two disjoint sets.

(Imagine a string stretched horizontally from left to right. Cutting

the string partitions the fibers of the string into two disjoint sets.

Some fibers lie to the left of the cut and some to right. No fiber

lies in both parts.) In just the same way, Dedekind’s cut partitions

the set of rational numbers into two sets, which we will call A

1

and

A

2

. Let A

1

be the set of rational numbers to the left of the cut, and

let A

2

be the set of rational numbers to the right of the cut. Each

number in A

1

is, therefore, less than each number in A

2

. But what

about P, the point at which the cut was made? Three possibilities

exist: P may belong to A

1

; P may belong to A

2

; or P may not belong

to either A

1

or A

2

.

If P belongs to A

1

, it is the largest element in A

1

, and it is also a

rational number because every element in A

1

is a rational number.

Also, if P belongs to A

1

, then P does not belong to A

2

because the

sets share no points in common. Consequently, the set A

2

does

not have a smallest number. To see why this is so, imagine that

A

2

did have a smallest number. Call that number Q. Because we

have already assumed that P belongs to A

1

and that A

1

and A

2

have

no elements in common, Q must be bigger than P, but between

any two rational numbers on the real line there is always a third

rational number distinct from both. If the third number existed, it

would not belong to either A

1

or A

2

, since it would be larger than

P and smaller than Q. This contradicts the fact that every rational

number belongs either to A

1

or A

2

. We conclude, therefore, that if

P belongs to A

1

, A

2

does not have a smallest element.

Now assume that P belongs to A

2

. Reasoning similar to that of the

preceding paragraph shows that A

1

cannot have a largest element.

Finally, suppose that P does not belong to either A

1

or A

2

.

Because every rational number belongs to either A

1

or A

2

, P must

38 BEYOND GEOMETRY

be an irrational number, but P corresponds to the unique number

that partitions the set of all rational numbers into the sets A

1

and

A

2

. The way that P divides the rational numbers also reveals which

irrational number corresponds to P. It is the unique number less

than every rational number in A

2

and greater than every rational

number in A

1

. (Only one real number satisfies both criteria.) In this

way, Dedekind showed that to each number corresponds exactly

one point and to each point corresponds exactly one number. He

concluded that the set of real numbers has the same continuity as

the line. (Notice that Dedekind’s correspondence allows us to use

the terms real number and point on the real line interchangeably, and

we will do exactly that in the next section.)

Georg Cantor and Set Theory

The German mathematician Georg Cantor (1845–1918) did more

than anyone else to place set theory at the center of mathemati-

cal thought. He was a creative mathematician with an unusual

background. In university, he studied philosophy and physics in

addition to mathematics. A mystic as well as a mathematician, he

hoped his research into the nature of infinite sets would reveal

something about the mind of God. The discoveries that Cantor

made about infinite sets were so unexpected that mathematics

journals were sometimes reluctant to publish his papers. Editors

were worried that the papers contained errors, although they

could find none. His research was so controversial that despite the

fact that he changed the history of mathematics, he was refused

a position that he wanted at the University of Berlin because of

the sensational nature of his discoveries. It was characteristic of

Cantor that he titled his Ph.D. thesis “In mathematics the art of

asking questions is more valuable than solving problems.”

Much of Cantor’s work involved the problem of classifying

infinite sets, and one of his main methods was the use of one-to-

one correspondences. When he could prove that a one-to-one

correspondence existed between two sets, he would conclude

that the two sets were equal in size. When he could show that a

one-to-one correspondence did not exist, he would conclude that

A New Mathematical Landscape 39

they were of different sizes. Cantor began by defining an infinite

set as any set that can be put into a one-to-one correspondence

with a proper subset of itself. (Recall that neither Galileo nor

Bolzano attempted to be precise about the sizes of the sets that

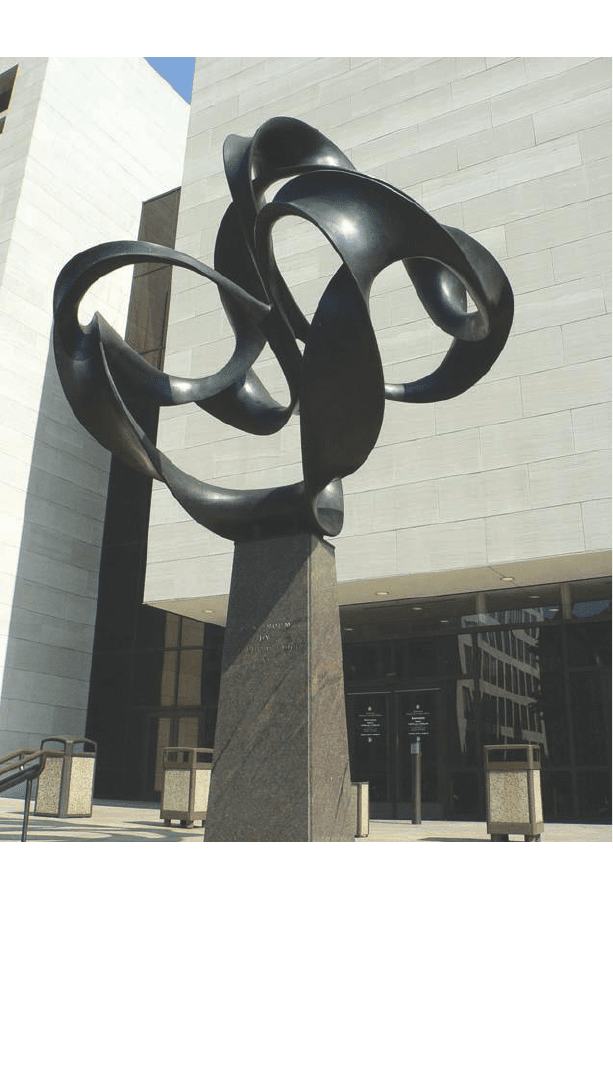

This sculpture by Charles Perry is titled Continuum. Cantor showed that

the continuum of real numbers cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence

with the set of all rational numbers. In other words, infinite sets come in

different sizes.

(Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum)