Strouthes D.P. Law and Politics: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PROCEDURAL

LAW

This

description

is of

orthodox political

economy.

It is

"orthodox"

in

that

it

remains faith-

ful

to the

style

of

analysis used

by

Marx

and

Engels. More recently, political economists have

been studying noncapitalist societies

and

show-

ing

that

even here there

are

upper classes

that

exploit members

of the

lower classes, just

as

Marx found

in

capitalist

and

feudal societies.

The

term

political'economy

is

today

often

used

to

refer

to an

actual economic system

in

which

the

economy

is

manipulated politically

by the

powerful

for

their

own

economic

benefit

and to

the

economic detriment

of

other people.

The

term

has

often

been used

to

describe

the

eco-

nomic

relationship between colonial powers (the

politically powerful

who

benefit economically)

and

the

indigenous peoples

of the

colonies

who

suffer

economically

from

the

colonial

relationship.

See

also

WORLD

SYSTEM.

Alverson,

Hoyt.

(1978)

Mind

in the

Heart

of

Darkness.

Marx, Karl,

and

Friedrich Engels.

(1968)

Karl

Marx

and

Friedrich

Engels:

Selected

Works

in

One

Volume.

Power

is

defined

as the

ability

to

influence

the

behavior

of

another

in a

way

that

is

desired.

We can

see, therefore, that

power

can

come

in

many forms.

There

is

mili-

tary power,

of

course, which

can be

used

to

force

an

entire nation

to

accede

to

another nations

demands.

There

is

also

the

power

a

child

may

have

over

his or her

parents when

she

sheds tears

to

induce them

to

behave

in the way

that

he or

she

wants.

One of the

more interesting sorts

of

power

to be

found

in any

society

is

supernatural power.

Many Jews, Christians,

and

Muslims attribute

supernatural

power

to

their God, even though

these same people

may

disdain

the

concept

of

magical causation

as

mere superstition.

The

Micmac, although

Catholic,

have

a

very

strong belief

in

supernatural power other than

that

coming

from

God.

They

believe

that

any-

one

with

great ability

or

skill

in one

kind

of ac-

tivity,

say

music,

lumber]

acking,

or

even speaking

the

Micmac language,

is

acknowledged

as a

kinapy

an

individual with supernatural power.

See

also

AUTHORITY; LEADER; POLITICAL

ANTHROPOLOGY

Lukes, Steven.

(1974)

Power:

A

Radical

View.

Strouthes, Daniel

P.

(1994)

Change

in the

Real

Property

Law

of

a

Cape

Breton

Island

Micmac

Band.

Procedural

law

regulates

the

legal process itself;

it

determines just

how le-

gal

actions

are

adjudi-

cated. Procedural

law

settles problems

of

juris-

diction, allocation

of

authority (who

is the

legal

authority),

the

sanctions that

may be

applied

in

a

particular case, court proceedings (such

as

whether

the

public

is to be

admitted

to the

court-

room),

and

matters pertaining

to the

process

of

appealing verdicts. Procedural

law

includes

the

laws

determining what

is a

proper legal hearing,

the

steps involved

in

such hearings, what con-

stitutes evidence

and

what evidence

may be ad-

mitted,

the

form

of

legal arguments

in a

legal

hearing,

who may

have standing

in a

legal case,

who may be

permitted

to

make arguments

in a

legal hearing,

if and in

what

form

testimony

is

203

PROCEDURAL

LAW

POWKR

PROCEDURAL

LAW

made,

and if and in

what

form

interrogation

takes

place.

In

short, procedural

law

regulates

all

facets

of the

conduct

of a

legal hearing

and

adjudication,

but not the

substantive laws

themselves.

One of the

parts

of

procedural

law in

some

legal systems

is the

making

of the

charge, which

outlines

the

offense

on

which

the

accused

is to

be

tried.

As

shown

in the

following decision

from

Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe),

the

particulars

of

the

charge

can be

very important (The

Rhode-

sian

Law

Reports

1966:

552-555).

REGINAV.HORNE

Appellate Division, Salisbury

Quenet,

J. P., and

Macdonald,

J. A.

2nd

August

and 2nd

September, 1966

Criminal

law-Copper

Control

Act

[Chapter

226]

-s. 6

(2)-contravention

of-essentials

ofof-

fence-not

alleged

in

charge-fatally

defective-

whether

appellant

can

waive

right

to

complain

of

irregularity

Appellant

was

charged with contravening

s. 6

(2)

of the

Copper

Control

Act

[Chapter

226],

but

the

charge omitted

to

allege that

the

per-

sons

from

whom

he

purchased

the

copper were

neither "dealers

nor

licensed

dealers."

It was

contended

by

appellant

that

this

was not an

essential element

of the

offence,

or, if it

was,

it

could

be

implied

from

the

charge. Alterna-

tively,

it was

contended that appellant

had

waived

his

right

to

complain

of the

irregular-

ity,

and the

proceedings were

not

vitiated.

Held,

setting aside

the

convictions

and

sentence:

(1)

That

the

words "other than

a

dealer

or

licensed dealer" constituted

an

essential

el-

ement

of the

offence,

and

were

not

simply

words

of

exception, exemption

or

excuse.

(2)

That

to

imply

an

essential element

of

an

offence,

from

a

charge which

did not al-

lege

it,

must mean that

an

accused

is

presumed

to

know

the

essential elements

of a

statutory

offence,

and, knowing them,

be

able

to

sup-

ply

any

words omitted

from

the

charge.

This

was

an

untenable argument.

(3)

That,

if a

charge disclosed

no

offence,

any

conviction under

it was

devoid

of

legal

effect,

and, even

with

an

appellant's

assis-

tance,

an

appeal court cannot validate such

proceedings.

M. R.

Tett

for the

appellant.

/

A. R.

Giles

for

the

respondent.

MACDONALD,

J.

A.:

The

appellant

was

convicted

of

contravening

s. 6 (2) of the

Cop-

per

Control

Act

[Chapter

226],

as

amended,

and

sentenced

to pay a fine of 30

pounds

or,

in

default

of

payment,

one

months imprison-

ment with hard labour.

Section

6 (2) of the Act

reads:

"No

person, including

a

dealer

or a

licensed

dealer, shall purchase

any

cop-

per

from

any

person other than

a

dealer

or

licensed dealer unless there

is

produced

to him by

such last mentioned person

such

documentary evidence

of his

title

to

sell such copper

as may be

prescribed

or a

certificate

of

clearance."

The

charge against

the

appellant reads:

"The accused,

at or

near Salisbury,

did

wrongfully

and

unlawfully

purchase

from

Mishek

and

Deni,

Africans there

being,

170

pounds

of

copper,

and the

said

Mishek

and the

said

Deni

not

produc-

ing at the

time

of

purchase

documentary

evidence

of

their title

to

sell such copper,

that

is to say

that

the

said Mishek

and

the

said

Deni

were

not at the

time

of the

purchase

in

possession

of a

certificate

of

clearance,

and

thus

the

said accused

did

commit

the

crime

of

contravening sec-

tion

6 (2) of the

Copper Control

Act

[Chapter

226]."

In the

course

of the

hearing

of the ap-

peal,

the

Crown submitted that

the

charge

is

fatally

defective,

because

it

omits

to

allege that

204

PROCEDURAL

LAW

Mishek

and

Deni

were neither dealers

nor li-

censed dealers.

Mr.

Tett

desires

that

the

appeal

be

con-

sidered

on its

merits,

and

submits

that

the

charge

is not

fatally

defective.

In

support

of

this submission,

he

contends that

the

words

"other than

a

dealer

or

licensed dealer"

and

the

words "unless there

is

produced

to him by

such

last mentioned person such documentary

evidence

of his

title

to

sell such copper

as may

be

prescribed

or a

certificate

of

clearance" con-

stitute "exceptions, exemptions, provisos,

ex-

cuses

or

qualifications" within

the

meaning

of

s.

134 (2) (b) of the

Criminal Procedure

and

Evidence

Act

{Chapter

31].

The

latter words

unquestionably constitute

an

"exception,

ex-

emption

or

excuse" within

the

meaning

of

that

section,

but the

former

words

are of the

very

substance

of the

offence

and, unless

it can be

said

that

those words

are to be

implied

in the

charge,

the

Crowns contention

that

it is fa-

tally defective must

be

upheld.

I am

satisfied

that

the

words "other than

a

dealer

or a

licensed

dealer" constitute

an

essential element

of the

offence,

for the

following reasons:

The

con-

duct prohibited

by the

section

is not the

pur-

chase

of

copper

but the

purchase

of

copper

from

a

person

who is

neither

a

dealer

nor li-

censed

dealer.

A

charge which alleged

no

more

than that

the

accused

had

purchased copper

would certainly

be

defective.

The

words con-

stitute

an

additional element

of the

offence,

and

are not

simply words

of

exception, exemp-

tion

or

excuse.

Mr.

Tett

submits,

in the

alternative, that,

although there

is no

express allegation that

Mishek

and

Deni

are

neither dealers

nor li-

censed

dealers, this allegation

is to be

implied

from

the

fact

that

the

charge clearly alleges

that

the

purchase

was

unlawful

by

reason

of

the

failure

of

Mishek

and

Deni

to

produce

ei-

ther documentary evidence

of

their

title

to

sell

or

a

certificate

of

clearance

at the

time

of the

purchase.

In

effect,

he

submits

that,

if the

Crown specifically alleges

that

an

accused per-

son

has

failed

to

comply with

the

requirements

of

an

"exception, exemption, proviso, excuse

or

qualification,"

the

Crown must

be

taken,

by

necessary implication,

to

have alleged

all

the

essential elements

of the

offense

itself.

The

basis

for

this submission, although

not

stated,

must necessarily

be

that

an

accused person

is

presumed

to

know

the

essential elements

of a

statutory

offence,

and, knowing them,

be

able

to

supply

any

words omitted

from

the

charge.

Mr.

Tetis

approach

is

clearly untenable,

and

Mr.

Giles

is

correct when

he

submits that there

is

nothing

in the

wording

of the

charge which

implies

the

inclusion

of the

words "other than

a

dealer

or a

licensed dealer."

Mr.

Tetfs

final

submission

is

that,

if the

omission

of

these words

is a

fatal

defect,

the

proceedings

are not

vitiated thereby, because

the

appellant,

in the

course

of the

hearing

of

the

appeal,

has

expressly waived

his

right

to

complain

of the

irregularity.

In R. v.

Henchel,

1920 A.D. 575,

SIR

JAMES

ROSE

INNES

said,

at p.

580:

"I do not

think that

any

court

of

appeal

would

be

justified

in

allowing

a

conviction

to

stand upon

a

charge sheet

which discloses

no

offence."

The

same view

was

expressed

by VAN

DEN

HEEVER,

J.

A.,

in

R.

v.

Preller,

1952

(4)

S.A.

452

(A.D.),

at

473:

"A

conviction

on a

charge which dis-

closes

no

offence

is, in

itself,

a

failure

of

justice

and a

legal impossibility,

and

should

not be

allowed

to

stand."

InRogerv.

R.,

1962

R.

&N.

385,MAISELS,

J.,

dealing,

on

appeal, with

a

charge which dis-

closed

no

offence,

said,

at p.

386:

"But

SCHRIENER,

A. C. J, at p.

280, points

out

what

INNES,

C.

J.,

says,

in

effect,

in

Herschel's

case,

is

that,

al-

though

a

defect

of the

kind

now

under

discussion could have been cured

at the

trial,

it

cannot

be

cured

on

appeal."

And the

learned judge concluded,

at p.

388:

"...

that,

as the

indictment discloses

no

offence,

this court

is

obliged

to set

aside

the

conviction."

205

PROCEDURAL

LAW

Since

the

charge under consideration dis-

closes

no

offence,

the

conviction

of the

appel-

lant

was

devoid

of

legal

effect,

and it

must

necessarily follow

that

this court,

as an

appeal

court, even

with

the

appellant's assistance,

is

powerless

to

validate

the

proceedings.

If, as

Mr.

Tett

has

endeavoured

to

establish

in

deal-

ing

with

the

merits

of the

appeal, there

are

certain

facts

which

the

Crown,

to its

advan-

tage, might have established

at the

trial

but

did

not, this court, indeed, would possibly

as-

sist

in

bringing

about

a

miscarriage

of

justice

if

it

were

to

hold

that

the

appellant

at

trial

was

placed

in

jeopardy

on a

charge under

s. 6 (2)

of

the Act

when,

in

law,

he was

not.

The

charge discloses

no

offence,

and the

conviction

and

sentence,

for

this reason, must

be set

aside.

QUENET,

J. P.,

concurred.

One of the

best described examples

of the

steps

taken

in a

proper legal hearing,

an

impor-

tant

part

of

procedural law,

is

that

of the Ti-

betan legal system

as it

existed before

the

Chinese invasion

in

1959.

The

progression

of a

civil

case

is as

follows.

In

order

to

initiate

a

proper legal action,

a Ti-

betan

litigant

had to

present

his or her

case

to

the

court,

and the

court

had to

declare

it a

proper

case

before

accepting

it. The

petitioner

was

then

called

before

the

court,

and the

petition pre-

sented.

Next,

the

petitioner

was

questioned

by

the

legal authorities.

Following

this,

the

other

party

to the

dispute

was

called

before

the

court,

and

he or she

made

a

reply

to the

petition.

The

petitioner then made

a

response

to the

second

party

s

reply,

after

which

he or she was

ques-

tioned again. After this

took

place,

the

second

party

had a

chance

to

reply again

to the

petitioner's

statements.

It was

following this that

any

evidence pertinent

to the

hearing

was

pre-

sented.

At

this point, each party

to the

case

was

brought

before

the

court

and

questioned

by the

legal authorities.

The

next stage

of the

hearing

saw

witnesses called

before

the

court

to

give their

statements,

and

this

was

followed

by

their ques-

tioning.

If the

court demanded more informa-

tion,

it

ordered

an

investigation, which

was

presented

formally

to the

court.

If the

court

deemed

it

necessary,

the

veracity

of the

parties

to the

case could

be

tested.

If the

court

found

either party

to be

lying,

it

punished

him or

her.

The

court then made

its

decision

and

wrote

it

down

in a

special document. Both parties were

recalled

before

the

court

to

hear

the

decision,

and

they

then

left

to

ponder

it.

After

a

period

of

time, both parties were again recalled

to the

court

to

give their opinions

of the

decision.

The

par-

ties

then either signed

a

clause

signifying

their

agreement

to the

decision,

or

refused

to

sign

it,

signifying

that

they were opposed

to the

deci-

sion

as an

unfair

one. Copies

of the

decision were

then exchanged

by the

litigants.

The

case

was

closed

in the

following man-

ner.

The

court accepted

the

litigants'

signatures

or

refusals

to

sign

the

decision.

Any

payments

of

court costs were then made.

The

terms

of the

decision,

usually involving

the

payment

of

dam-

ages

from

one

party

to

another

or the

sanction-

ing of

either

or

both parties

by the

court, were

then carried out. Following

this,

the two

parties

to the

case made

a

formal reconciliation with

each

other. Finally,

as the

case

concluded,

the

court

had the

option

to

send

the

case

to a

higher

authority,

and

either

or

both

of the

parties

had

the

option

to

appeal

the

case.

The

series

of

steps

in the

legal hearing

in-

volving

a

crime

in

Tibet

were usually

fewer

be-

cause

the

identity

of the

criminal

was

usually

known

and the

facts

of the

case

were more eas-

ily

determined.

The

identity

of the

alleged crimi-

nal

was

usually known because most

Tibetans

lived

in

small towns

in

which everyone knew

everyone

else, including those

who

frequently

behaved

badly

or who

held grudges.

Once

a

crime occurred,

the

victim

or his or

her

family either made

a

petition

to the

legal

206

PROCEDURAL

LAW

authorities

or

informed their local governmen-

tal

official

of the

crime.

If the

alleged criminal

was

considered likely

to try to

escape,

he or she

was

arrested immediately, before

the

official

in-

vestigation

of the

crime.

The

crime

was

then

investigated

by a

clerk

from

the

district

office.

The

investigation consisted

of

collecting

evi-

dence

and

interviewing

the

victim

and his or her

family.

At

this point,

the

identity

of the

alleged

criminal

was

clearly determined

by the

investi-

gating

officials,

and he or she was

arrested

if he

or

she had not

been previously. From this point

until

the

legal authority made

his

decision

in the

case,

the

criminal

was

presumed guilty,

and any

show

of

remorse

he or she

made

was

weighed

in

his or her

favor

in

determining sanctions.

The

criminal

was

brought

before

the

court

and

the

crime

was

announced

by the

govern-

mental

official

who

presided

as the

legal author-

ity

in the

case.

The

criminal

was

then whipped

and

placed

in

jail,

and

sometimes

in

stocks

and

fetters

as

well.

The

legal authority then began

to

review

the

case

and to

hear evidence.

The

criminal,

the

victim,

and the

victim's

family

were

interviewed

by the

judge.

If the

facts

established

in

the

hearing

did not

conform

to the

criminal's

testimony,

the

judge

had the

option

of

having

the

criminal whipped.

If the

criminal's

testimony continued

to

dis-

agree

with

the

testimony

of the

victim

and the

victim's

family,

as

well

as the

other

facts

estab-

lished

in the

case,

the

case could

be

prolonged

indefinitely.

In

most instances,

on the

other hand,

the

legal authority

was

able

to

devise

a

writ-

ten

statement

of the

facts

with

which

all

parties

could agree.

The

statement, which also included

the

sanctions

to be

imposed upon

the

criminal,

was

read

to the

assembled parties

to the

case,

who

in

turn were given time

to

discuss

the

provisions

of

the

statement privately. Unless

the

case

was

to be

referred

directly

to a

higher legal author-

ity,

all

parties

to the

case then signed their agree-

ment

to the

statement.

If a

long-term

punishment, such

as

laboring

for the

victim

or

victim's

family

or

being kept under house arrest,

was

to be

imposed, guarantors

for the

imposition

of

these sanctions

had to

sign

the

statement

as

well.

Following

the

signing,

the

criminal

(or his

family,

employer, landlord,

or the

owner

of the

land

on

which

the

crime

was

committed) paid

the

monetary

fines

imposed

by the

legal author-

ity.

Court

costs

and

fees

were then paid. Finally,

the

physical sanctions imposed upon

the

crimi-

nal

were carried out, which

may

have included

whippings

and

fetters.

As

mentioned above,

the

Tibetans made

use

of

various devices, including oaths,

to

test

the

veracity

of the

parties

to a

dispute. Persons tak-

ing an

oath would have

to

loosen their hair

and

remove

amulets, knives,

and

religious strings.

Then,

while

standing before

the

portrait

of a

powerful

god or

goddess, they would swear that

they were telling

the

truth.

The god or

goddess

was

believed

to

punish those

who

lied.

In one

case,

a

woman

who

took

an

oath

that

she had

not

committed sorcery began

to

bleed

from

her

nose

shortly

after

taking

the

oath,

and she

later

died,

her

death being

attributed

to the

goddess

Lhamo,

before

whose portrait

she had

taken

the

oath.

If

both

parties

to a

case

agreed

to an

oath,

the

oath

was

considered

to

settle

the

case

be-

cause

the

supernatural sanctions

that

the

gods

and

goddesses applied

in the

case

of

liars were

so

sure

and so

severe. However,

not all

people

believed

in the

efficacy

of an

oath,

and

they were

allowed

to

prohibit

it

from

the

legal hearing.

Also, some people were alleged

to

employ

de-

ception

in the

taking

of

oaths,

and

opposing

parties

could

refuse

to

accept

the use of the

oath.

If the

established

facts

of a

case were

too

vague

for a

clear decision

to be

made

by the au-

thorities,

the

parties would

often

agree

to

allow

the

case

to be

decided

by the

rolling

of the

dice.

Again,

the

power

of the

supernatural came into

play.

Before rolling

the

dice, shouts were uttered

for

the

Dharma Protector Gods

to

make

the

dice

207

PURGE

roll

in

such

a way as to

indicate

the

truth

of the

case.

Each party rolled,

and the one who

rolled

the

highest number

won the

case.

It was

believed

that

if the

dice gave

the

highest score

to the

party

in

the

wrong,

the

gods would later punish

the

party

who won

unfairly.

The

Tibetans

also

had a

device, called

a Bab

or

Ba>

which they employed

to

ensure

that

con-

tractual obligations would

be

honored.

It set

forth

fees

that

a

party

who did not

perform

ac-

cording

to a

contract would have

to

pay.

Finally,

the

Tibetans

at one

time made

use

of

ordeals.

First,

the

person

who was to

give tes-

timony spoke

and

then

was

given

a

test

in

which

supernatural

forces

would determine

if the

tes-

timony

was

true

or

false.

These

tests typically

consisted

of a

person coming

in

contact with some

very

hot

item, such

as

boiling

oil or

water

or hot

stones.

In one

type

of

ordeal,

the

persons tongue

was

touched

to a

piece

of hot

iron.

The

individu-

als

were then examined

the

next day,

and if

blis-

ters were

found

they were deemed

to

have lied

in

giving testimony.

The use of

ordeals

in

Tibet

had

ended decades

before

the

Chinese invasion.

Yet

another

way of

handling

a

legal case

is

presented

by the

Native American people

of the

Cochiti

Pueblo

of New

Mexico.

There,

the

pro-

cedure

is

much simpler

and

faster.

A

person with

a

complaint brings

it to the

pueblo

s

governor.

The

governor himself investigates

the

matter.

He

then makes

a

decision

on the

basis

of the

infor-

mation

he has

collected

and

upon legal prece-

dent.

If he

cannot make

a

fair

decision

on

this

basis

alone,

he

convenes

a

court

of his

lieuten-

ant

and

members

of the

council.

The

court

then

hears

the

testimony

of the

parties

to the

case

and

of all of the

witnesses.

The

officers

of the

court then discuss

the

matter

and

render

a

deci-

sion.

The

governor then announces

the

decision

and

the

sanction,

if the

offender

warranted one;

sanctions

in the

early

1950s

included

fines,

com-

munity service,

and

whippings.

See

also

OATH;

ORDEAL;

SUBSTANTIVE

LAW.

Barton,

Roy F.

(1973

[1949])

The

Kalingas:

Their

Institutions

and

Custom

Law.

French, Rebecca. (1990)

The

Golden

Yoke:

A Le-

gal

Ethnography

of

Tibet

Pre-19

59.

Lange, Charles

H.

(1990

[1959])

Cochiti:

A

New

Mexico

Pueblo,

Past

and

Present.

The

Rhodesian

Law

Reports,

1966. (1966)

Ed-

ited

by H. G.

Squires.

A

purge

is the

removal

of

suspected

or

actual

political opponents

from

any

sort

of

human group, whether they

be po-

litical,

geographic,

or

commercial

in

nature.

Purges usually

refer

to the

expulsion

of

relatively

large numbers

of

people

at a

single time.

In

com-

mercial

groups, purges

may be

accomplished

through firings.

In

more purely political groups,

purges

are

accomplished through deportations,

exiles,

imprisonments,

and

killings.

The

most

infamous

use of

purges

was in the

former

Soviet Union, especially under

the re-

gimes

of

Lenin

and

Stalin. During

the

Soviet

period, direct

political

action

was

used

to

bring

about purges

far

more

frequently

than

was the

legal system, although

the

legal system

was not

inactive either. Under Stalin,

for

instance,

the

legal code

was

enlarged with

a

great number

of

new

criminal

offenses

that

were

of a

political

nature.

Most

of the

truly large-scale purges took

place under

Lenin's

CHEKA

(All-Russian

Ex-

traordinary Commission

for the

Suppression

of

Counterrevolution

and

Sabotage)

and

Stalin's

NKVD

(People's

Commissariat

for

Internal

Affairs),

political action groups with tremendous

powers

to

kill

or

imprison

in

labor camps

with-

out

legal trials.

The

activities

of the

CHEKA

208

PURC;I:

PURGE

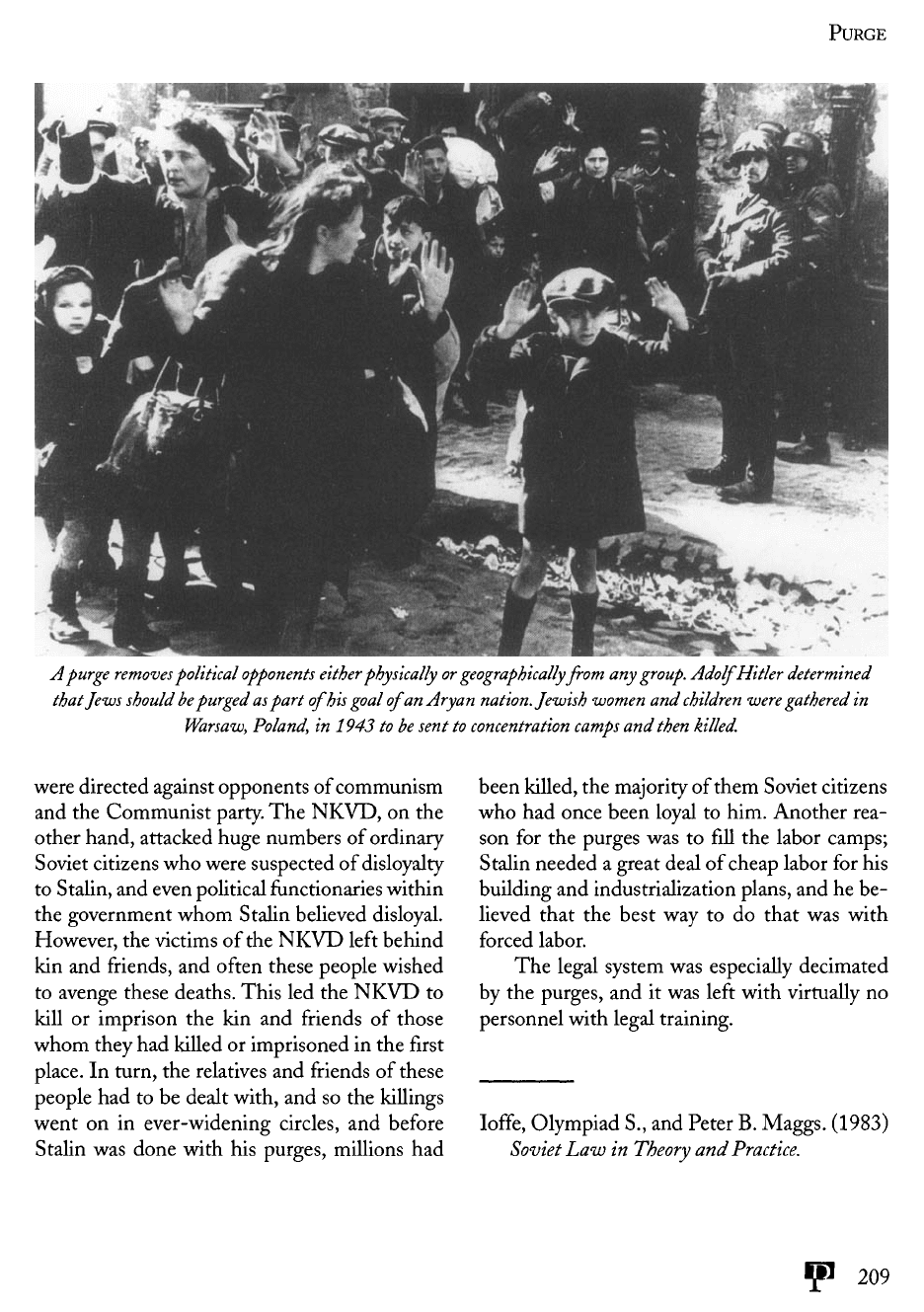

A

purge

removes

political

opponents

either

physically

or

geographically

from

any

group.

Adolf

Hitler

determined

that

Jews

should

be

purged

as

part

of

his

goal

of

an

Aryan nation. Jewish women

and

children

were

gathered

in

Warsaw,

Poland,

in

1943

to be

sent

to

concentration

camps

and

then

killed.

were

directed against opponents

of

communism

and

the

Communist party.

The

NKVD,

on the

other hand, attacked huge numbers

of

ordinary

Soviet citizens

who

were suspected

of

disloyalty

to

Stalin,

and

even political functionaries within

the

government whom Stalin believed disloyal.

However,

the

victims

of the

NKVD

left

behind

kin and

friends,

and

often

these people wished

to

avenge these deaths.

This

led the

NKVD

to

kill

or

imprison

the kin

arid

friends

of

those

whom they

had

killed

or

imprisoned

in the first

place.

In

turn,

the

relatives

and

friends

of

these

people

had to be

dealt

with,

and so the

killings

went

on in

ever-widening circles,

and

before

Stalin

was

done

with

his

purges, millions

had

been

killed,

the

majority

of

them Soviet citizens

who had

once been loyal

to

him. Another rea-

son

for the

purges

was to fill the

labor camps;

Stalin needed

a

great deal

of

cheap labor

for his

building

and

industrialization plans,

and he be-

lieved

that

the

best

way to do

that

was

with

forced

labor.

The

legal system

was

especially decimated

by

the

purges,

and it was

left

with virtually

no

personnel

with legal training.

loffe,

Olympiad

S., and

Peter

B.

Maggs.

(1983)

Soviet

Law in

Theory

and

Practice.

209

REAL

PROPERTY

Real property

refers

to

property

that

is not

movable, such

as

land

and

buildings

that

are

permanently attached

to

the

land.

Real property also includes

the

miner-

als

beneath

the

surface

of the

land.

The

term

real

property

was

given this name because earlier

English speakers believed

that

land

and

perma-

nent buildings

had

more intrinsic worth than

moveable

items,

or

"personal

property,"

and

thus

was

more genuine

or

"real."

The

term

real

prop-

erty

may

also

be

abbreviated

as

realty. Real

prop-

erty

law is

sometimes called

land

tenure.

The

laws

that

govern

the use and

transfer

of

rights

in

real

property are,

in

European, U.S., Canadian,

and

many

other legal systems,

different

from

those

regulating personal property.

In the

United States,

for

example,

sale

of

rights

in

real property usually

requires

the use of a

deed, whereas

the

sale

of

rights

in

personal property usually does not.

Likewise, real property

is

frequently leased,

whereas

personal property

is not

normally leased.

The

division

of

property along these lines does

not

appear

in all

cultures.

In

many socie-ties,

for

example, buildings

are

personal property.

Among

the

Ifugao

of the

Philippines,

for

example, houses

are

frequently disassembled

and

moved

by

their owners. Houses

are

sometimes

sold

and

then moved

for use by the

purchaser.

Among

the

Ifugao,

it is the

house

that

has

value,

not the

land upon

which

it is

situated. Likewise,

trees

such

as

coconut,

coffee,

and

areca

trees also

have

value

and are

owned, whereas

the

land upon

which they grow

is

valueless

and

therefore can-

not be

sold

or

owned.

Under

the

laws

of the

United

States,

Canada,

and the

countries

of

Europe,

all

land

that

is not

owned

by

individuals

or

groups

of

individuals

is

owned

by the

state

or the

crown.

This

is not so in

many societies, including

the

Ifugao.

There,

only three kinds

of

land

may be

owned.

Land

that

is

used

for the

cultivation

of

rice

and

forested land

are

owned

by an

individual

or

family

until they

are

sold

or

given

to

another

party. Land used

for the

cultivation

of

sweet

potatoes

is

owned

by the

cultivator

so

long

as he

cultivates

it;

when

it

grows over

with

weeds

and

trees,

it may be

used

by

anyone

who

cares

to

clear

the new

vegetation

and

grow another

few

crops

of

sweet potatoes.

All

other land

is

unowned

or

free

land

that

may be

used

by

anyone.

The

types

of

ownership

are

linked

to the

length

of

time

that

the

land

is

valuable. Forested lands provide

wood

in

perpetuity unless

too

many trees

are

cut.

Likewise, rice

fields,

or

padis,

produce rice

as

long

as

there

is

sufficient

water

for the

rice plants

to

thrive. Both

of

these types

of

land

are

owned

in

perpetuity.

As

well,

they

may be

pawned

to

another

if the

owner needs money;

the

lender

has

the

right

to

farm

the

rice

fields

until

the

owner

pays

back

the

money

he has

been lent.

Sweet potato

fields

only produce usable amounts

of

sweet potatoes

for a few

years, until weeds

grow

to the

point

that

cultivation becomes more

work

than

it is

worth.

Thus,

sweet

potato

fields

are

only owned

as

long

as

they

are

cultivated.

Among

the

highly mobile Naskapi Indians

of

Labrador, Canada, there

was

traditionally

no

ownership

of

land.

The

only rights

the

Indians

211

R

REAL

PROPERTY

had, which could

be

transferred, were

rights

of

ususfructus,

or

usufruct.

Ownership

of

land,

which

is a

bundle

of

rights including those

of

usufruct,

made

no

sense

to the

Naskapi

because

they were only interested

in

using

the

animals

and

trees

on the

land

before

they moved

on to a

new

place where

the

animals

and

trees were

in

greater abundance.

The

various bands within

the

area

would give each other

usufructuary

rights;

for

instance,

one

band gave another

the

right

to

hunt porcupines

on the

land

it

used

in

exchange

for

the

right

to

hunt bears

on the

other band's

land. Individuals

and

families

had

exclusive

hunting rights

on

specific

tracts

of

land,

but

this

may

have been because

of

competition

for

fur-

bearing animals

as a

result

of the

fur

trade, which

was

introduced

by

white people.

These

tracts

of

land have been called hunting territories,

and

their

use is

governed

by the

headman

of the

band,

who

must also resolve disputes over hunting ter-

ritory use.

Hunting

territory boundaries

are

made

up of

natural

features

of the

land, particu-

larly streams

and

rivers.

The

Gusii people

of

western Kenya actually

developed

for

themselves

a new

system

of

real

property

law in the

period

from

1925

to

1950.

This

development occurred

as a

result

of a

great

increase

in

population.

The

Gusii

are

farmers

who

raise

both

crops

and

livestock.

Prior

to the

1920s,

there

was

plenty

of

land

for

everyone

to

farm.

If one

could

not get

land

from

one's

par-

ents,

one

simply went

into

the

bush

and

cleared

whatever clan-owned land

one

wanted (all Gusii

lands

were owned collectively

by

clans).

By the

1920s,

however, there were

so

many people

in

Gusii society that land

was

becoming

insuffi-

cient

in

quantity. Land that

one man had in

mind

for

his

young

son's

future

use

often

turned

out

to be

land that

a

neighbor

had in

mind

for his

own

son's

future

use. Also, people began

to put

up

fences

and

hedges

to

keep their neighbors

from

encroaching

on

their

own

farm

lands. Dis-

putes over land became more common,

and for

the first

time people began

to

take these dis-

putes

to

legal authorities.

Legal

authorities

weighed

the

strength

of

each claim

to

land

and

made decisions

as to

where

the

proper bound-

ary

lines should lie.

They

also made decisions

in

cases

concerning

the

future

use of

land (for

the

later

use of the

children

of the

parties

to the

dis-

pute).

In

such

cases,

they decided

the

boundary

lines

of

lands that were

to

become

farms

years

later.

The

main purpose

of the

decisions

of the

Gusii legal authorities concerning land

was not

to

preserve

the

rights

of

those

who had

strong

claims

to

land ownership,

but to

provide

all

Gusii

with relatively equal amounts

of

land.

Thus,

the

goal

of the

Gusii land tenure system

is

very dif-

ferent

from

our

own.

Our

land tenure system

strives

to

protect

the

ownership rights

of

valid

landowners,

no

matter

how

much land

one

owns.

Thus,

in our

society, there

are

people

who may

own

real estate worth hundreds

of

millions

of

dollars, while other people

are

homeless.

The

Gusii system strove

to

eliminate great

differences

in

the

amount

of

land members

of the

society

could own,

at

least

in its

earliest stages.

Various

aspects

of a

society's

real property

law can

tell

a

great deal about other aspects

of

the

culture. Among

the

Yoruba

of

Nigeria, there

traditionally

was no

such thing

as

tenancy.

This

was

because

the

land

for a

community

was

con-

trolled

by the

community

and

owned

by

indi-

viduals.

Thus,

if one is by

descent

a

member

of

the

community,

one

thereby

has

automatic

ac-

cess

to

land ownership.

If one is a

stranger

to

the

community, then

one

either becomes

a

natu-

ralized member

of the

community,

and

thus able

to own

land within

its

bounds,

or

moves

on to

another place. Naturalization meant,

for a

man,

that

he

married women within

the

community

and

swore loyalty

to the

community's chief.

See

also PERSONAL PROPERTY.

Barton,

Roy F.

(1969

[1919])

Ifugao

Law.

212

REASONABLE

MAN

Lips, Julius

E.

(1947)

"Naskapi

Law."

Transac-

tions

of the

American Philosophical

Society

37(4):

378-492.

Lloyd, Peter

C.

(1962)

Yoruba

Land Law.

Mayer, Philip,

and

lona

Mayer. (1965)

"Land

Law in the

Making."

In

African

Law:

Adap-

tation

and

Development,

edited

by

Hilda

Kuper

and Leo

Kuper,

51-78.

REASONABLE

MAN

The

term

reasonable

man

refers

to a

society's

ideas

about what

is

reasonable

behavior

by

determining

what

a

reasonable

man

would

do in a

given situ-

ation.

These

standards

are not

part

of any

society's

codified law,

but

rather come into play

in

judicial proceedings

and

vary

from

society

to

society.

The

concept

of the

reasonable

man is

common

to all

legal systems, although

the

people

using

it may not be

able

to

state

it as a

distinct

concept.

Among

the

Barotse

of

Africa

the

concept

of

the

reasonable

man was

applied

in

determin-

ing

basic legal standards.

The

Barotse have

two

standards

in

their law:

(1) the

reasonable

man

and

(2) the

ideal man.

The

ideal

man is one who

behaves

in the

best possible manner

in all

con-

ditions. Such

a man

obviously does

not

exist.

But if one

behaves

at the

minimally correct stan-

dards

of

behavior,

one

behaves

as a

reasonable

man

would and, therefore,

in a

legal fashion.

In

Western legal systems

and

some other

places,

the

reasonable

man is a

hypothetical

man

who is

used

in the

judgment

of an

accused per-

son.

The

actions

of the

accused

are

compared

with what

a

reasonable, normal person would

do in the

circumstances

in

which

the

accused

found

himself during

or

after

the

commission

of a

crime

or

civil

offense.

Would

a

reasonable

man

who had

just committed

a

robbery

be

run-

ning down

the

street wearing clothes other than

athletic clothes? Yes.

The

shooting

of a

police-

man

by Lee

Harvey Oswald

was

consistent

with

what

a

reasonable

man

would have done

after

shooting

the

president

of the

United States

and

being confronted

by the

policeman. Acting

as a

reasonable

man

would

after

commission

of an

offense

is

taken

as a

form

of

proof

of

guilt.

The

concept

of the

reasonable

man

comes

up in the law in

many

different

guises

in

differ-

ent

societies.

It

does

not

always

refer

to

people

who

have committed crimes

and who are

being

judged

on the

basis

of

their behavior

after

the

crime.

For

example,

an

Ifugao

man or

woman

can

divorce

a

spouse

if

that

spouse

is

unreason-

ably

jealous

or

unreasonably lazy.

If an

Ifugao

person uses another person's rice field,

and the

owner wants

it

back,

the

owner must

pay the

one who

worked

the field for his

labor, unless

that payment

is

unreasonable.

Among

the

Nuer

of

Africa,

if two

groups

are

feuding with each other,

and a man

from

the

first

group kills

a man

from

the

second group,

the

killing

is

considered

a

malicious rather than

an

accidental

killing,

since this

is

reasonable

be-

havior

for

members

of

groups that

are

feuding

with each other.

The

same

is

true

for the

Kalingas

of the

Philippines

and

there have even been

cases

there

in

which accidental woundings between

members

of

feuding groups have been called

deliberate

by the

person

who

committed

the

wounding,

so

that

he

could claim

to be

carrying

out his

obligations

in the

feud.

Among

the Tiv

of

West

Africa,

the

concept

of

the

reasonable

man

came into play

in

deter-

mining

the

degree

of

behavior that constituted

an

offense.

For

example,

the Tiv

considered

it

reasonable

for a man to

beat

his

wife,

but

unrea-

sonable

and

thus illegal

for him to

beat

her to

the

point that

she

could

not

work.

It was

rea-

sonable

for a man to

want

to

sleep with

as

many

women

as

possible,

but

unreasonable

and

there-

fore

illegal

to

commit incest

in

doing

so. It is

reasonable

(though wrong)

to

steal

from

people

213