Strouthes D.P. Law and Politics: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

REVITALIZATION

MOVEMENTS

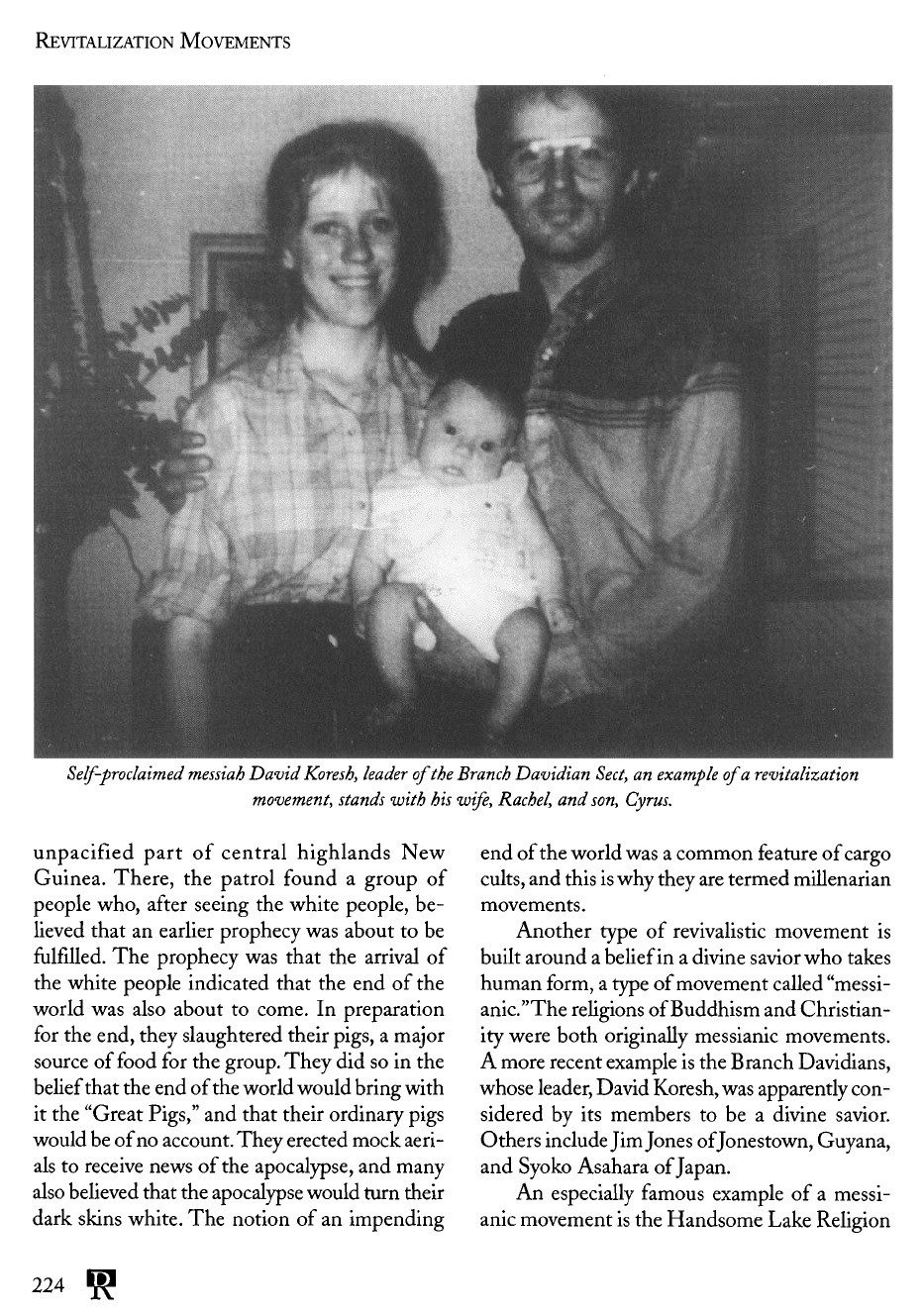

Self-proclaimed

messiah

David

Koresh,

leader

of

the

Branch

Davidian

Sect,

an

example

of

a

revitalization

movement,

stands

with

his

wife,

Rachel,

and

son,

Cyrus.

unpacified

part

of

central highlands

New

Guinea.

There,

the

patrol found

a

group

of

people who,

after

seeing

the

white people,

be-

lieved

that

an

earlier prophecy

was

about

to be

fulfilled.

The

prophecy

was

that

the

arrival

of

the

white people indicated that

the end of the

world

was

also about

to

come.

In

preparation

for

the

end, they slaughtered their pigs,

a

major

source

of

food

for the

group.

They

did so in the

belief that

the end of the

world would bring with

it the

"Great

Pigs,"

and

that their ordinary pigs

would

be of no

account.

They

erected mock aeri-

als

to

receive news

of the

apocalypse,

and

many

also

believed

that

the

apocalypse would turn their

dark skins white.

The

notion

of an

impending

end of the

world

was a

common

feature

of

cargo

cults,

and

this

is why

they

are

termed

millenarian

movements.

Another

type

of

revivalistic movement

is

built around

a

belief

in a

divine savior

who

takes

human

form,

a

type

of

movement called

"messi-

anic."The

religions

of

Buddhism

and

Christian-

ity

were both originally messianic movements.

A

more recent example

is the

Branch Davidians,

whose leader, David Koresh,

was

apparently con-

sidered

by its

members

to be a

divine savior.

Others include

Jim

Jones

of

Jonestown, Guyana,

and

Syoko Asahara

of

Japan.

An

especially

famous

example

of a

messi-

anic

movement

is the

Handsome Lake Religion

224

RIGHTS,

CHILDREN'S

of

Iroquois Indians

of New

York State

and

Ontario.

In the

1700s,

the

Iroquois, demoral-

ized

by

military

defeat,

the

loss

of

land,

new

dis-

eases,

and

alcohol, heard

a new

voice, that

of

Handsome Lake,

a

Seneca (one

of the

Iroquois

tribes).

Handsome

Lake's

prophecy stressed

a

fusion

of

traditional Iroquois religious beliefs,

Christianity, abstention

from

the

consumption

of

alcohol,

and a

strengthening

of

family

ties.

The

Handsome Lake Religion survives today

with

a

substantial following.

A final

type

of

revitalization movement

is

the

revivalistic,

a

type

of

movement

that

em-

phasizes

a

return

to an

earlier

form

of the

cul-

ture,

in

whatever

form

the

movement leaders

portray

it,

whether such

a

form

actually once

existed

or

not.

An

example

of

this type

of

move-

ment

is the

Gush

Emunin

(bloc

of the

faithful)

movement

in

Israel.

This

movement emphasized

the

revival

of

Zionist ideology, Zionism being

a

movement

for

Jews

to

settle Palestine, which

had

been

largely dormant since

the

creation

of the

state

of

Israel. Zionist ideology includes

the

idea

that

in the

past,

in

biblical times,

the

Jews were

a

great

and

heroic people.

The

Gush

Emunin

stresses

a

return

to the

kind

of

strict religious

observance

that, adherents believe, characterized

the

behavior

of the

ancient Jews

who had

been

so

great.

It

also

has as one of its

recurrent themes

the

land

of

Palestine, which

the

ancient Jews

controlled

and

which modern Jews must once

again

control

if

they

are to

return

to

their

former

greatness.

Thus, movement

followers

believe that

the

lands

won in the

wars

of

1967

and

1973

are

of

crucial

importance

and

must never

be

surren-

dered. Members

of the

Gush

Emunin were

the

ones

who

illegally occupied houses

in the

Sinai

in

an

effort

to

prevent

its

return

to

Egypt, which

the

government

of

Israel

had

decided

to do to

promote peace.

The

Gush

Emunin

has

since

de-

veloped into

a

bureaucratic organization

with

specialized arms

to

pursue

its

political

and

reli-

gious aims.

One of

these arms

is the

Amana,

which

is

specifically

dedicated toward creating

and

preserving settlements

in

Israeli-occupied

territories.

In

short,

the

Gush

Emunin

was a

suc-

cessful

revitalization movement

in the

respect

that

it

became

a

standard

feature

of the

Israeli

political scene with

a

constant presence

and in-

fluence

on

national politics.

Not all

revitalization movements

are so

suc-

cessful.

The

Ghost

Dance Religion ended tragi-

cally

with

the

deaths

of

many people,

as did

the

Branch Davidians,

the

People's

Temple

of

Jonestown, Guyana,

and a

cargo cult

in

Mela-

nesia

whose members attempted

to fight the

Japanese

navy

in

World

War II and who

believed

that

their magic would protect them against

Japanese bullets.

Other

revitalization movements

have

simply evaporated

as

adherents came

to

realize

that their leaders were

not

messiahs,

or

that

the

millennium

was not

going

to

come,

or

that

the

cargo would never arrive.

Lewellen,Ted

C.

(1992)

Political

Anthropology:

An

Introduction.

2d ed.

Wallace, Anthony

F. C.

(1956)

"Revitalization

Movements." American Anthropologist

58:

264-281.

Worsley, Peter

M.

(1959) "Cargo Cults."

Scien-

tific

American

200:

117-128.

RIGHTS,

CHILDREN'S

The

legal rights

of

chil-

dren within

the

family

make

up an

important

part

of the field of

fam-

ily

law.

Among

the

Kuria people

of

Tanzania,

children traditionally belonged

to the man who

was

at the

time

of

birth

married

to the

child's

mother; marriage,

in

this society,

was

finalized

by

the

payment

of a

bride-price

by the

husband.

However,

it was not

unheard

of for a

child

to

225

RIGHTS,

CHILDREN'S

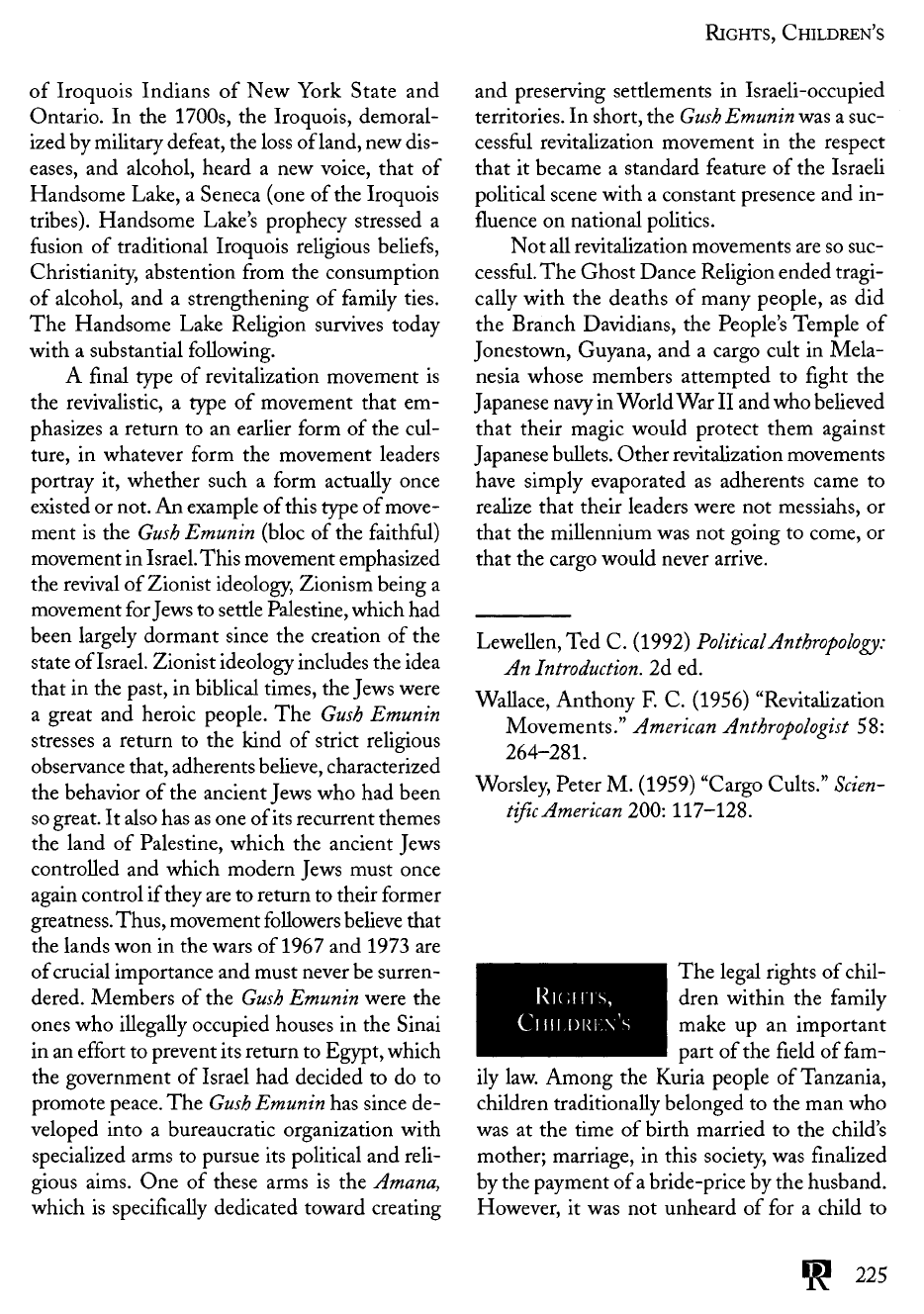

A

Pakistani

boy

digs

clay

with

two men

to

feed

brick

kilns near

Rawalpindi

in

1994.

The

legal

rights

of

children

make

up a

large

part

of

family

law as

well

as

laws

involving

their exploitation

as

laborers.

have

been born into

and

raised

in the

house

of a

man

with

whom

the

mother

was

living, even

though

she was

legally married

to

another man.

Under traditional law,

the

child still belonged

to

the man who was

married

to the

mother, even

if

the

child never

met him and

even

if he or she

knew

only

the man

with whom

her

mother lived,

the

man who was

often

his or her own

natural

father.

This

law is

known

as the

patrilineal principle.

In

later times, when

the

national courts

(as

opposed

to the

Kuria legal authorities) estab-

lished jurisdiction over

the

Kuria

people,

the law

changed.

The

national courts considered

it

cruel

and

against

the

interests

of the

child

to

remove

the

child

from

the

only home

he or she had

ever

known

and put him or her

into

the

house

of the

mother's

husband, especially

if the man

with

whom

the

woman

was

living

was the

child's

natural

father.

In

other words,

the

national courts

considered

the

child's rights

as

well

as the

rights

of the

parents.

The

question

for the

judges

was

how to

balance

the

traditional rights

of the fa-

ther

under

the

patrilineal principle with

the in-

terests

of the

children.

One

early attempt

to

achieve

this balance

was to

name

the

husband

of

the

mother

the

father,

but to

give custody

of

the

children

to the

mother.

The

mother's

hus-

band also received

the

right

to

arrange

his

children's

marriages

and to

receive

the

bride-price

paid

for his

daughters. Still later,

the

courts said

226

RIGHTS,

HUMAN

that

in

cases

in

which women

who

deserted their

husbands

and

whose children thus were

the

prod-

uct

of

unions

with

other men,

the

children

be-

longed

to the

mothers

and not to the

husbands.

The

law,

in

attempting

to

improve

the

con-

ditions

for

children

in

cases

in

which their

moth-

ers

have

left

their husbands,

has

given rights over

the

children

to the

mothers.

This

has

made

it

difficult

to

preserve

the

bride-price arrangement

for

two

reasons.

First,

a man

might think

that

he

should

not pay a

bride-price

if he is not go-

ing to

have

any

rights

in the

children, because

his

wife

might

run

away

and his

children would

in

later

life

support

the

wife,

and

perhaps

her

lover,

but not

him. Secondly,

a man

might

be

tempted

to

forgo marriage altogether.

He

could

live

with

a

woman, have children,

and

then

the

children would

in

later

life

support their mother

and, since

he is

their

mother's

lover, support

him

as

well;

in

this type

of

arrangement,

the man

could acquire

all of the

benefits

of

marriage

with-

out

having

to pay the

bride-price.

In

short,

the

change

in the

rights

of

children

in

Kuria

society

has

had

far-reaching

effects

on the law and on

the

very basis

of

Kuria society.

Rwezaura, Barthazar Aloys.

(1985)

Traditional

Family

Law and

Change

in

Tanzania:

A

Study

of

the

Kuria

Social

System.

RIGHTS,

HUMAN

Interest

in the

basic

rights

of

individuals goes

far

back

in

human his-

tory; such rights

are

mentioned

in

documents

such

as the Old

Testament,

the

Magna Carta,

and

the

U.S. Declaration

of

Independence.

However,

it is

only since

the end of

World

War

II

that human rights have emerged

as a

major

focus

of

worldwide concern.

The

emergence

of

human rights

and its

continuation

as a

major

worldwide issue

is the

result

of a

number

of

fac-

tors.

These

include

the

genocide

and

other large-

scale

human rights violations

of

World

War II,

the

erosion

of

colonialism,

and the

demand

for

rights

by

indigenous

and

minority peoples.

The

basic definition

and

framework

for the

subsequent consideration

of

human rights

is

con-

tained

in the

Universal Declaration

of

Human

Rights, adopted

and

proclaimed

by the

United

Nations General Assembly

as

resolution

217 A

(III)

of 10

December 1948.

This

document,

re-

printed

in

full

below, establishes

as a

moral prin-

ciple

that

all

human beings

are

entitled

to

certain

human rights

and

freedoms.

The

Universal Dec-

laration

has

been followed

by

numerous other

documents

focusing

on

specific

rights

or

catego-

ries

of

rights pertaining

to

genocide, protection

of war

captives

and

victims, collective bargain-

ing, prostitution, children,

refugees,

prisoners,

slavery,

marriage, forced labor, racial discrimi-

nation, cultural rights, political asylum, mental

retardation, hunger

and

malnutrition, disabled

persons, religion,

and

medical care.

Human rights violations involving ethnic

groups

are

purposeful

acts intended

to

harm both

individuals

who are

members

of a

specific

eth-

nic

group

and the

group itself. Such violations

commonly include mass killings, deportations,

rapes,

denial

of

food

and

housing, torture,

de-

tention

without

due

process, destruction

of

dwellings

and

material possessions,

and

destruc-

tion

of

cultural, educational,

and

religious insti-

tutions.

When

the

national government

is

directly involved

in

ethnic conflict

it may be a

perpetrator

of

rights violations while

at the

same

time render itself unavailable

as a

protector

of

rights. Similarily, when ethnic groups

use

ter-

rorism

against civilian populations, they

too are

guilty

of

human rights violations.

Efforts

to

apply

the

concept

of

human rights

to

ethnic groups

has

produced three controversies

227

RIGHTS,

HUMAN

in

the

international community.

The first is

whether

the

concept

of

human rights

as set

forth

in

the

Universal Declaration

and

subsequent

documents applies only

to

individuals

or

whether

it

also applies collectively

to

groups such

as

reli-

gious groups, ethnic minority groups, indigenous

peoples, etc.

It is

clear

from

the

policy

and

prac-

tice

in

many nations that, with regard

to

certain

matters, ethnic groups

do

have

a

collective, cor-

porate identity.

For

example, land claims

and

other rights asserted

by

Native Americans have

been

adjudicated

in

courts

or

settled

by

admin-

istrative bodies within

the

framework

of the

group's

rights. Similarly,

in New

Zealand,

the

Maori right

to

political representation

is a

group

right,

not an

individual

right.

However, when

it

comes

to

rights

defined

as

human rights,

the

question

of

whether those rights apply only

to

individuals

or

also

to

groups

is not

clear.

Hu-

man

rights advocates argue

for the

latter view

as

a

way of

more broadly protecting human rights,

while many national governments adhere

to the

individual rights only position

as a

means

of

defining

human rights

as an

internal matter.

Efforts

at

applying rights protection

to

entire

groups

has led to

many

as yet

unanswered ques-

tions, such

as:

What

is an

ethnic minority?

Is

group size

a

reasonable criteria

for

measuring

group existence? Does

a

group need

to be

local-

ized

to be a

group?

How

does

one

measure

group cohesiveness?

The

second controversy concerns

the

issue

of

differentiation

versus discrimination that

of-

ten

arises

when

one

group

is

afforded

some rights

denied

to

other groups.

The

controversy

arises

because

in

many nations ethnic minority groups

want

to be

treated

differently,

often

in

order

to

maintain their cultural integrity

or to

regain

rights lost during times

of

colonial domination.

The

question

is

whether this

differential

treat-

ment

of

groups—as

in

affirmative

actions pro-

grams

for

African-Americans

in the

United

States

or

programs

for

Untouchables

in

India—

is

a

form

of

discrimination, either against

indi-

vidual members

of the

group

or

members

of

other groups

who are not

eligible

for

differen-

tial treatment. Outsiders sometimes

see

these

special

group rights designed

to

reverse

the ef-

fects

of

past discrimination

as a

form

of

reverse

discrimination.

In

general, groups that

are

given

collective rights tend

to be

ones with

a

clear eth-

nic

identity

and

membership,

who are

different

from

other groups,

and who can be

awarded

rights

on the

basis

of

objective criteria that also

can

be

applied

to

other groups.

The

third controversy

is

over

the

cross-

cultural validity

of

current conceptions

of hu-

man

rights, which

are

seen

in

some non-Western

nations

as

reflecting Western values

and

there-

fore

as

ethnocentric.

This

ethnocentrism

is

seen

by

some experts

as a

hurdle

to the

universal adop-

tion

and

enforcement

of

human rights

protec-

tions. From

a

cross-cultural perspective, much

attention

has

been

focused

lately

on

Islam

and

Islamic nations

and the

need

to

balance univer-

sal

human rights concepts with such Islamic

practices

as the use of

amputation

as a

punish-

ment

for

crime.

UNIVERSAL

DECLARATION

OF HU-

MAN

RIGHTS

PREAMBLE

Whereas

recognition

of the

inherent

dignity

and

of the

equal

and

inalienable

rights

of all

members

of the

human

family

is the

founda-

tion

of

freedom,

justice

and

peace

in the

world,

Whereas

disregard

and

contempt

for

human

rights have resulted

in

barbarous acts which

have outraged

the

conscience

of

mankind,

and

the

advent

of a

world

in

which human beings

shall

enjoy

freedom

of

speech

and

belief

and

freedom

from

fear

and

want

has

been pro-

claimed

as the

highest aspiration

of the

com-

mon

people,

228

RIGHTS,

HUMAN

Whereas

it is

essential,

if man is not to be

com-

pelled

to

have recourse,

as a

last resort,

to

rebel-

lion against tyranny

and

oppression,

that

human

rights should

be

protected

by the

rule

of

law,

Whereas

it is

essential

to

promote

the

devel-

opment

of

friendly

relations between nations,

Whereas

the

peoples

of the

United Nations

have

in the

Charter

reaffirmed

their

faith

in

fundamental

human rights,

in the

dignity

and

worth

of the

human person

and in the

equal

rights

of men and

women

and

have determined

to

promote social progress

and

better standards

of

life

in

larger

freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged

them-

selves

to

achieve,

in

cooperation

with

the

United Nations,

the

promotion

of

universal

respect

for and

observance

of

human rights

and

fundamental freedoms,

Whereas

a

common understanding

of

these

rights

and

freedoms

is of the

greatest impor-

tance

for the

full

realization

of

this pledge,

Now, therefore,

The

General Assembly,

Proclaims this Universal Declaration

of Hu-

man

Rights

as a

common standard

of

achieve-

ment

for all

peoples

and all

nations,

to the end

that

every individual

and

every organ

of

soci-

ety,

keeping this Declaration constantly

in

mind, shall strive

by

teaching

and

education

to

promote respect

for

these rights

and

free-

doms

and by

progressive measures, national

and

international,

to

secure

their

universal

and

effective

recognition

and

observance, both

among

the

peoples

of

Member States them-

selves

and

among

the

peoples

of

territories

under their jurisdiction.

Article

1

All

human beings

are

born

free

and

equal

in

dignity

and

rights.

They

are

endowed

with

reason

and

conscience

and

should

act

towards

one

another

in a

spirit

of

brotherhood.

Article

2

Everyone

is

entitled

to all the

rights

and

free-

doms

set

forth

in

this Declaration, without dis-

tinction

of any

kind, such

as

race, color, sex,

language, religion, political

or

other opinion,

national

or

social origin, property, birth

or

other status.

Furthermore,

no

distinction shall

be

made

on

the

basis

of the

political, jurisdictional

or in-

ternational status

of the

country

or

territory

to

which

a

person belongs, whether

it be in-

dependent, trust, non-self-governing

or un-

der any

other limitation

of

sovereignty.

Article

3

Everyone

has the

right

to

life,

liberty

and se-

curity

of

person.

Article

4

No one

shall

be

held

in

slavery

or

servitude;

slavery

and the

slave

trade shall

be

prohibited

in all

their

forms.

Article

5

No one

shall

be

subjected

to

torture

or to

cruel,

inhuman

or

degrading treatment

or

punishment.

Article

6

Everyone

has the

right

to

recognition every-

where

as a

person

before

the

law.

Article

7

All are

equal

before

the law and are

entitled

without

any

discrimination

to

equal protec-

tion

of the

law.

All are

entitled

to

equal pro-

tection against

any

discrimination

in

violation

of

this Declaration

and

against

any

incitement

to

such discrimination.

Article

8

Everyone

has the

right

to an

effective

remedy

by the

competent national tribunals

for

acts

229

RIGHTS,

HUMAN

violating

the

fundamental

rights

granted

him

by

the

constitution

or by

law.

Article

9

No one

shall

be

subjected

to

arbitrary arrest,

detention

or

exile.

Article

10

Everyone

is

entitled

in

full

equality

to a

fair

and

public hearing

by an

independent

and

impartial tribunal,

in the

determination

of his

rights

and

obligations

and of any

criminal

charge against him.

Article

11

1.

Everyone charged

with

a

penal

offense

has

the

right

to be

presumed innocent until proved

guilty according

to law in a

public trial

at

which

he has had all the

guarantees necessary

for his

defense.

2. No one

shall

be

held guilty

of any

penal

offense

on

account

of any act or

omission

which

did not

constitute

a

penal

offense,

under

national

or

international law,

at the

time when

it was

committed.

Nor

shall

a

heavier penalty

be

imposed than

the one

that

was

applicable

at

the

time

the

penal

offense

was

committed.

Article

12

No one

shall

be

subjected

to

arbitrary inter-

ference

with

his

privacy,

family,

home

or

cor-

respondence,

nor to

attacks upon

his

honor

and

reputation. Everyone

has the

right

to the

protection

of the law

against such interference

or

attacks.

Article

13

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to

freedom

of

move-

ment

and

residence within

the

borders

of

each

State.

2.

Everyone

has the

right

to

leave

any

coun-

try,

including

his

own,

and to

return

to his

country.

Article

14

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to

seek

and to

enjoy

in

other countries asylum

from

persecution.

2.

This

right

may not be

invoked

in the

case

of

prosecutions genuinely arising

from

non-

political crimes

or

from

acts contrary

to the

purposes

and

principles

of the

United Nations.

Article

15

1.

Everyone

has the right to a

nationality.

2. No one

shall

be

arbitrarily deprived

of his

nationality

nor

denied

the

right

to

change

his

nationality.

Article

16

1. Men and

women

of

full

age, without

any

limitation

due to

race, nationality

or

religion,

have

the

right

to

marry

and to

found

a

family.

They

are

entitled

to

equal

rights

as to

mar-

riage, during marriage

and at its

dissolution.

2.

Marriage shall

be

entered into only with

the

free

and

full

consent

of the

intending spouses.

3.

The

family

is the

natural

and

fundamental

group unit

of

society

and is

entitled

to

protec-

tion

by

society

and the

State.

Article

17

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to own

property

alone

as

well

as in

association with others.

2. No one

shall

be

arbitrarily deprived

of his

property.

Article

18

Everyone

has the

right

to

freedom

of

thought,

conscience

and

religion; this right includes

freedom

to

change

his

religion

or

belief,

and

freedom,

either alone

or in

community with

others

and in

public

or

private,

to

manifest

his

religion

or

belief

in

teaching, practice, wor-

ship

and

observance.

Article

19

Everyone

has the

right

to

freedom

of

opinion

and

expression; this right includes

freedom

to

hold opinions without

interference

and to

seek,

receive

and

impart information

and

ideas

through

any

media

and

regardless

of

frontiers.

Article

20

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to

freedom

of

peace-

230

RIGHTS,

HUMAN

fill

assembly

and

association.

2. No one may be

compelled

to

belong

to an

association.

Article

21

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to

take part

in the

government

of his

country, directly

or

through

freely

chosen representatives.

2.

Everyone

has the

right

to

equal access

to

public service

in his

country.

3.

The

will

of the

people shall

be the

basis

of

the

authority

of

government:

this

will

shall

be

expressed

in

periodic

and

genuine elections

which shall

be by

universal

and

equal

suffrage

and

shall

be

held

by

secret vote

or by

equiva-

lent

free

voting procedures.

Article

22

Everyone,

as a

member

of

society,

has the

right

to

social security

and is

entitled

to

realization,

through national

effort

and

international

co-

operation

and in

accordance

with

the

organi-

zation

and

resources

of

each State,

of the

economic,

social

and

cultural rights indispens-

able

for his

dignity

and the

free

development

of

his

personality.

Article

23

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to

work,

to

free

choice

of

employment,

to

just

and

favorable

conditions

of

work

and to

protection against

unemployment.

2.

Everyone, without

any

discrimination,

has

the

right

to

equal

pay for

equal work.

3.

Everyone

who

works

has the

right

to

just

and

favorable

remuneration ensuring

for

him-

self

and his

family

an

existence worthy

of hu-

man

dignity,

and

supplemented,

if

necessary,

by

other means

of

social protection.

4.

Everyone

has the

right

to

form

and to

join trade unions

for the

protection

of his

interests.

Article

24

Everyone

has the

right

to

rest

and

leisure,

in-

cluding reasonable limitation

of

working hours

and

periodic holidays with pay.

Article

25

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to a

standard

of

liv-

ing

adequate

for the

health

and

well-being

of

himself

and of his

family,

including food,

clothing, housing

and

medical care

and

nec-

essary

social services,

and the

right

to

security

in

the

event

of

unemployment, sickness, dis-

ability, widowhood,

old age or

other lack

of

livelihood

in

circumstances beyond

his

control.

2.

Motherhood

and

childhood

are

entitled

to

special care

and

assistance.

All

children,

whether born

in or out of

wedlock, shall

enjoy

the

same social protection.

Article

26

1.

Everyone

has the

right

to

education. Edu-

cation shall

be

free,

at

least

in the

elementary

and

fundamental stages. Elementary educa-

tion shall

be

compulsory. Technical

and

pro-

fessional

education shall

be

made generally

available

and

higher education shall

be

equally

accessible

to all on the

basis

of

merit.

2.

Education shall

be

directed

to the

full

de-

velopment

of the

human personality

and to

the

strengthening

of

respect

for

human rights

and

fundamental

freedoms.

It

shall promote

understanding, tolerance

and

friendship

among

all

nations, racial

or

religious groups,

and

shall

further

the

activities

of the

United

Nations

for the

maintenance

of

peace.

3.

Parents have

a

prior

right

to

choose

the

kind

of

education

that

shall

be

given

to

their

children.

Article

27

1.

Everyone

has the

right

freely

to

participate

in the

cultural

life

of the

community,

to

enjoy

the

arts

and to

share

in

scientific

advancement

and its

benefits.

2.

Everyone

has the

right

to the

protection

of

the

moral

and

material interests resulting

from

any

scientific, literary

or

artistic production

of

which

he is the

author.

Article

28

Everyone

is

entitled

to a

social

and

interna-

tional order

in

which

the

rights

and

freedoms

231

RIVALRY

set

forth

in

this

Declaration

can be

fully

realized.

Article

29

1.

Everyone

has

duties

to the

community

in

which alone

the

free

and

full

development

of

his

personality

is

possible.

2. In the

exercise

of his

rights

and

freedoms,

everyone shall

be

subject only

to

such

limita-

tions

as are

determined

by law

solely

for the

purpose

of

securing

due

recognition

and re-

spect

for the rights and

freedoms

of

others

and

of

meeting

the

just requirements

of

morality,

public order

and the

general welfare

in a

demo-

cratic society.

3.

These

rights

and

freedoms

may in no

case

be

exercised contrary

to the

purposes

and

prin-

ciples

of the

United Nations.

Article

30

Nothing

in

this Declaration

may be

inter-

preted

as

implying

for any

State, group

or

per-

son

any

right

to

engage

in any

activity

or to

perform

any act

aimed

at the

destruction

of

any

of the

rights

and

freedoms

set

forth herein.

See

also

INTERNATIONAL

LAW

An-Na'im,

Abdullahi

A.,

ed.

(1992)

Human

Rights

in

Cross-Cultural

Perspective:

A

Quest

for

Consensus.

Brownlie,

Ian.

(1992)

Basic

Documents

on Hu-

man

Rights.

Felice,

William.

(1992)

The

Emergence

of

Peoples'

Rights

in

International

Relations.

Heinz, Wolfgang

S.

(1991)

Indigenous

Popula-

tions,

Ethnic Minorities

and

Human Rights.

Lawson, Edward,

ed.

(1991)

Encyclopedia

of

Human Rights.

Ramaga,

Philip

V.

(1993)

"The

Group Concept

in

Minority Protection." Human Rights

Quarterly

15:

575-588.

Stavenhagen, Rodolfo.

(1987)

"Ethnic

Conflict

and

Human Rights:

Their

Interrelationship."

Bulletin

of

Peace

Proposals

18:

507-514.

Van

Dyke, Vernon. (1985) Human

Rights,

Eth-

nicity,

and

Discrimination.

Whalen,

Lucille. (1989) Human

Rights:

A

Ref-

erence

Handbook.

RIVALRY

A

rivalry

is a

state

of

competition between

two

individuals

or

groups,

and is

usually

long-standing.

Among

the

various

men's

clubs

of the

Crow Indians,

ri-

valries

could become fierce.

The

clubs were

of-

ten

paired

in

rivalrous activities

and

were always

trying

to

best each other.

One of

these

was

brav-

ery

in

battle,

in

which each side tried

to

beat

the

other

in

counting coup (being

the first to be

able

to go up to an

enemy

and

touch him, often with

a

special coup stick). Counting coup

was

very

dangerous, because while

you

were trying

to

touch

the

enemy,

he and all of his

compatriots

were

usually trying

to

kill you.

If a

club

was the

first to

count coup,

it

could sing

the

songs

of the

club

with whom

it had a

rivalry; otherwise, this

stealing

of

songs

was not

allowed.

The

rivalry

helped

to

make

the

clubs competing with each

other very brave,

as in the

following case.

One of the

men's societies known

as the Fox

club

was in

rivalry with another known

as the

Lumpwood club.

As

they were approaching

the

enemy

in

battle

one

day,

a Fox man

snuck

up

some

distance

in the

direction

of the

enemy with

the

Fox's

coup stick,

and

then stopped.

A

Lumpwood

man

went

up to him and

asked

him

if

he was

going

to

count coup.

The Fox man re-

plied that

he was

afraid

to go. The

Lumpwood

man

then took

the Fox

coup stick, used

it to

touch

an

enemy,

and

then

ran

back part

of the

way

and put the

coup stick

in the

ground

be-

232

RIVALRY

233

tween

the two

enemy parties.

He

dared

the Fox

men

to get

their

own

coup stick back,

but

none

would.

In

order

to

humiliate

the

Foxes

further,

the

Lumpwoods claimed

the

right

to

sing

the

Fox's

songs

that

night,

and the

Foxes

had to

bor-

row

songs

from

other clubs

so

that

they would

have

something

to

sing.

Crow

men's

club rivalries were restricted

to

the

warm seasons;

the

rest

of the

time

the

mem-

bers

of the

clubs were

friendly

and

helpful

to-

ward each other.

Lowie,

Robert

H.

(1956

[1935])

The

Crow

Indians.