Stephenson M. Patriot Battles. How the War of Independence Was Fought

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

fire and ice 259

the Rall and Lossberg regiments surrendered, followed shortly after

by the Knyphausen regiment, which had tried but failed to cross the

Assunpink. It was all over by 9:30 am.

Given the ferocity of the street fighting (Sergeant Joseph White

recalled that his “blood chill’d to see such horror and distress, blood

mingling together, the dying groans . . . The sight was too much to bear”)

and the overwhelming numerical superiority of artillery and muskets

available to Washington, it is a dramatic illustration of the nature of

the warfare of the period and the effectiveness of its weaponry that

out of 1,500 Hessians, only 22 were killed and 83 wounded (834 were

captured). The Americans losses were astonishingly small: two men

dead of exposure and two wounded: Captain William Washington, a

distant cousin of the commander in chief, shot through both hands; and

a future president, Lieutenant James Monroe, who survived an almost

fatal shoulder wound.

On 26 and 27 December Washington led his triumphant, exhausted,

and drunk army—Joseph Reed reported that “the soldiers drank too

freely to admit of Discipline or Defence,” even though Washington had

ordered forty hogsheads of rum destroyed—with its prisoners and loot

back to Pennsylvania. They had crossed not only the Delaware but also

a psychological barrier: the frontier that separates those who believe

they are condemned to be beaten and those who are convinced they are

destined to win. The battle may have been only a large-scale raid, but

its impact was massive. A Loyalist, Nicholas Cresswell, reported on the

sea change in his patriot neighbors: “A few days ago they had given up

the cause for lost. Their late successes have turned the scale and now

they are all liberty made again.”

15

The raggedy-assed soldiery had done

something extraordinary, and they knew it. Equally extraordinary, they

would be back in Trenton in only three days.

The second battle of Trenton, although given fairly short shrift in most

histories, is full of interest not only for the student of Washington’s

command style but also as a fine example of what might be called the

patriot battles 260

“organic” evolution of strategy: the role of happenstance as an important

factor in warfare (much to the chagrin of those historians who prefer

to ascribe intention and planning that only hindsight lends to what in

reality is the chaotic ricochet of events).

First, Washington had no clearly thought-out strategy after

Trenton.

16

What happened next was taken, in his characteristically

aggressive and opportunistic manner, on the fly. What triggered

Washington’s return to Trenton was, ironically, Cadwalader’s eventual

successful landing in New Jersey on 27 December. There they now were,

1,800 men stuck out on their own limb. After the usual war council

Washington decided to support Cadwalader with everything he had: “a

considerable force,” by Washington’s own estimation.

During the twenty-ninth and the thirtieth Washington sent over

6,800 men and a formidable artillery train to Trenton, ranging them on

the high ground on the southern bank of the Assunpink.

17

In retrospect

it all seemed perfectly logical. Lure Cornwallis to attack a strongly held

defensive position and then, while he banged at the front door, slip out

the back and capture the enemy’s rear bases (including that succulent

£70,000).

It is an appealing theory (seemingly sanctified by events), except

that almost everything points in the opposite direction. Washington had

placed his men in the gravest peril and risked everything to chance.

It is difficult to understand how the strategic benefit could ever have

outweighed the massive risk. He had deployed his army with its back to

the Delaware without what in modern jargon would be called “an exit

strategy.” In fact, many in his army were panicked by the situation in

which they now found themselves. A Virginian, Ensign Robert Beale, in

the American center, recognized the danger: “This was the most awful

crisis, no possible chance of crossing the River; ice as large as houses

floating down, and no retreat to the mountains, the British between

us and them.”

18

Captain Stephen Olney concurred: “It appeared to

me then that our army was in the most desperate situation I had ever

known it; we had no boats to carry us across the Delaware, and if we

had, so powerful an enemy would certainly destroy the better half

fire and ice 261

before we could embark.”

19

One of Washington’s generals, Arthur St.

Clair, referred to the “probability of defeat.”

Before he sallied out of Princeton to do battle with Washington,

Cornwallis had been urged by Colonel von Donop, who knew the

country behind the American lines, to take a route that could be used to

flank the American right. Cornwallis, with the airy self-confidence of

the blinkered, decided to stick with his frontal strategy. It was on just

such arbitrary turns of the cards that Washington’s fate hung.

The British and Hessian column was delayed by a hit-and-retreat

maneuver, carried out brilliantly by Colonel Edward Hand and Colonel

Nicholas Haussegger, which bought valuable time for Washington to

consolidate his positions on the Assunpink. Once in Trenton, inspiration

seems to have abandoned Cornwallis, who accepted battle entirely on

Washington’s terms. He ordered attack after attack—all inspiringly

heroic, all bloodily sterile—on the bridge and one or two other main

choke points across the Assunpink, which, of course, Washington had

taken very particular care to defend in depth with his most experienced

troops, interspersed with the more fragile militia units. The fighting

at the bridge was fierce, and Washington’s own conduct there is an

exemplar of the detachment that was so highly prized by officers of

his social class. With his horse’s chest pressed against the bridge rail he

made a flamboyant gesture of nonchalance in the face of danger. “The

firm, composed, and majestic countenance of the General inspired

confidence and assurance in a moment so important and critical,”

remembered Private John Howland.

20

American fire tactics at the bridge provide a valuable insight into

the tendency to shoot high during the stress of battle, perhaps caused

by involuntary flinching at the moment of firing. (The same tendency

had plagued the British attackers at Breed’s Hill and would again at the

battle of Princeton.) To counter it, Colonel Charles Scott instructed his

Virginians:

Now I want to tell you one thing. You’re all in the habit of shooting

too high. You waste your powder and lead, and I have cursed you

patriot battles 262

about it a hundred times. Now I tell you what it is, nothing must

be wasted, every crack must count. For that reason boys, whenever

you see them fellows first begin to put their feet upon this bridge do

you shin ’em. Take care now and fire low. Bring down your pieces,

fire at their legs, one man Wounded in the leg is better a dead one

for it takes two more to carry him off and there is three gone.”

21

As brilliant as Washington’s defense was that evening of 2 January,

one question begged to be answered: what now? Cornwallis’s army of

some 6,000, despite a few bloody noses, was not going away and almost

certainly would eventually have opened up the patriot right flank.

Even with his advantage in artillery (forty compared with Cornwallis’s

twenty-eight) Washington was hardly likely to take the offensive. To

cap it, there were British reserves at Maidenhead and Princeton which,

momentarily, would be mobilized.

Quitting while ahead must have been a particularly appealing

notion to Washington at that point, but there is no evidence he had a

plan to extricate the army from the predicament in which he had placed

it. Washington, in council that evening, expressed his own pessimistic

forecast, as recorded by Major James Wilkinson on the American right

wing: “The situation of the two armies were known to all; a battle was

certain, if he kept his ground until the morning, and in case of an action

a defeat was to be apprehended; a retreat by the only route thought of,

down river, would be difficult and precarious.” He called for advice.

General Arthur St. Clair pointed out the cross-country back-road

route that would lead into the undefended southeastern perimeter of

Princeton six miles away to the east. Brilliantly, it offered the prospect

of escape and a chance to attack. Not only that; it offered the only hope,

and Washington grasped it with both thankful hands.

The night was exceedingly dark, and, true to form, the weather

turned in Washington’s favor. A hard freeze came down, transforming

the glutinous mud of the previous few days into a good solid base—“as

hard as pavement,” noted a soldier—for carts, artillery, and infantry.

Although Washington employed the usual ruses—campfires kept

burning, some men left to make conspicuous noise of entrenching,

fire and ice 263

and so on—his departure was certainly noticed by the British, who,

taking it for a flanking attack, made the entirely understandable but

completely inappropriate dispositions. Most histories have Cornwallis

curling his disdainful aristocratic lip while making a complete ass of

himself by pronouncing, “We will bag the fox tomorrow.” It makes a

good story, but, sadly, there is no evidence he used the phrase (although

foxy Washington certainly was).

Early on the morning of 3 January Washington’s column, marching

undetected up the Quaker Road that approached Princeton from

the southeast, came to the Stony Brook. Here Washington detached

Greene’s division to follow the road that ran alongside the brook, north

to the main Princeton-Trenton road, while he and Sullivan with the

main force (approximately 5,000) carried on toward the town. Greene

was to destroy the bridge where the main road crossed the brook, which

would hinder any attempt by Cornwallis to double back to Princeton.

At this point events began to unfold with the randomness that is more

characteristic of battle than chess-game tidiness.

The commander of the Princeton garrison, Lieutenant Colonel

Charles Mawhood, had been instructed by Cornwallis to bring part of

his garrison across to Trenton, and at 5:00 am on the third he duly set

off down the main road with the 17th and 55th Foot (700 or so men in

total) and eight guns, leaving the 40th Foot to hold the town. Not far

into their journey, the British column spotted Sullivan and Washington

over to the east. Greene’s force, 1,500 strong and working its way up the

ravine of Stony Brook, remained undetected, though it soon became

aware of the redcoats on the main road.

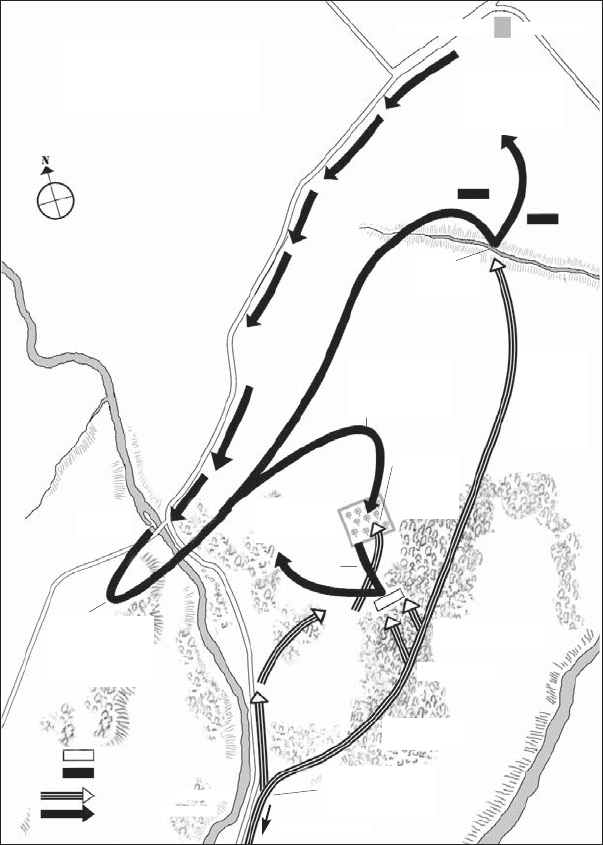

Princeton

3 January 1777

Post Road

Nassau Hall

Frog’s

Hollow

Ravine

Worth’s

Mill

T o T renton

William

Clark’s apple

orchard

Princeton

Mawhood with

17th and 55th

Foot starts for

Trenton

Mawhood sights

Washington’s

main force and

turns around

Greene and

Mercer peel off

from main column

Washington

and Sullivan

Sullivan

continues

to

Princeton

Mawhood and

17th Foot strike

Mercer in

orchard

55th and 40th

Foot retreat

when pressed by

Sullivan

Mercer

overrun

by

Mawhood

Mercer

killed

B

r

i

t

i

s

h

r

e

t

r

e

a

t

M

e

r

c

e

r

a

n

d

G

r

e

e

n

e

Washington peels

off to support

Cadwalader

40th Regiment

55th

Regiment

S

t

o

n

y

B

r

o

o

k

S

t

o

n

y

B

r

o

o

k

American

British

American movements

British movements

fire and ice 265

Mawhood immediately decided to attack Sullivan. He sent the 55th

and most of the artillery to occupy a small hill to the south of the road,

had his remaining infantry (supported by two fieldpieces), about 450

men, drop their packs and head off east in interception. At this point,

Greene’s vanguard (about 500 strong), commanded by General Hugh

Mercer, debouched from the ravine and moved to engage Mawhood,

who had no option but to turn his attention to this totally unexpected

threat. They clashed in an orchard on William Clark’s farm, and a brisk

firefight and artillery exchange developed.

What next transpired was a classic illustration of the vulnerability

of the rifle in a volley-fire situation. Although the British fired high

(“Their first shot passed over our heads”), it took much longer for

the patriot riflemen to reload, and this gave a critical advantage to

the British musketmen, armed with their murderous fourteen-inch

bayonets. Cohesion, unity, and discipline were key to eighteenth-century

battles where big, solid punches of concentrated fire counted far more

than the dissipated effect of numerous jabs. At this critical juncture

the American ranks began to lose their coherence despite attempts to

pull it back together. With a formality that would not have been out of

place at Minden or Malplaquet, Captain John Fleming instructed his

First Virginians, “Gentlemen, dress before you make ready.” It was a

classic command of eighteenth-century combat, intended to compact

the troops and intensify their volley, but Fleming was shot down as soon

as the words were out of his mouth, and the cohesion he was trying to

create fell apart. Mawhood, although considerably outnumbered, took

his opportunity, and the British moved in quickly. Mercer was bayoneted

multiple times (and would die some hours later), and his men broke,

streaming back into and destabilizing Cadwalader’s Pennsylvania

Associators as they moved up in support. It was the critical point of the

battle.

Washington’s personal intervention at the moment of crisis sheds

another light on his complex personality. All too often he is depicted

as a masterful civil servant, the great moderator, the inspired military

bureaucrat—all Eisenhower and no Patton. But here he showed those

characteristics so admired by his age: heroism and physical courage

patriot battles 266

displayed with imperturbability—the studied insouciance of the ancient

Roman. It was an inspiration, if also an agony, for those who watched

him only thirty yards or so from the British line with, as he later recalled,

“a thousand deaths flying around him,” rallying Cadwalader’s militia

and bringing his reinforcements into play. The tactical center, which

had disintegrated under the centrifugal force of panic, he now drew

back together again, tightened and unified it, and sent it forward to

deliver, as Washington ordered, “a heavy platoon fire on the march.”

22

Overwhelming numbers did the rest, and Mawhood’s corps broke and

ran. In the pursuit, Washington’s mask slipped for a while and he joined

in exuberantly, unrestrainedly, thoroughly enjoying himself—until

drear duty brought him back.

Mawhood’s stand had cost him dearly. For example, the 17th Foot

took 45 percent casualties (101 killed and wounded out of 224); the

British artillery lost 50 percent of its men. But it cost Washington more.

Princeton was taken, but the patriot army had been drained by the battle,

and there was no time to move on to Brunswick. As Washington would

later report to Congress, “In my judgement Six or eight hundred fresh

Troops upon a forced March would have destroyed all their Stores and

Magazines: taken (as we have learnt) their Military Chest containing

70,000 pounds and put an end to the war.”

23

But Cornwallis was now

closing in fast, and Washington’s only option was to head in to the high

lands around Morristown and hunker down for the winter.

17

The Philadelphia Campaign

BRANDYWINE, 11 SEPTEMBER 1777;

GERMANTOWN, 4 OCTOBER 1777;

AND MONMOUTH COURTHOUSE,

28 JUNE 1778

M

ost historians seem to agree—that it is impossible to agree.

Of all the campaigns of the war, none is as confusing, when

it comes to intention and execution, as that undertaken by

General William Howe in the late summer and early fall of 1777, which

led to his capture of Philadelphia (the seat of Congress and the unofficial

capital of the new United States).

One line of argument holds that Philadelphia was not important

strategically (as events would prove when the British eventually

abandoned it in 1778); nor, among a loose confederation of often

contentious states, did it have the symbolic potency of a national

capital. Howe, so the argument goes, was simply deluded, or stupid, or

both, to target it. But if he was, he was joined by George Washington

among others, who certainly thought the city worth the contention.

The political pressure that would compel the patriot commander to

defend the city was, from Howe’s point of view, a double blessing. It

prevented Washington from interdicting General John Burgoyne, as

he descended from Canada,

1

and it offered the chance of bringing the

patriot battles 268

patriot army to battle.

2

The most common accusation against Howe

has been his supposed predilection for the classic eighteenth-century

notion of maneuvering for territorial possession while avoiding battle,

and many have highlighted this as the main reason for Howe’s failure

during his years in command of the Royal Army in North America. A

counterargument can be made that Howe sought to bring Washington

to a decisive battle (Howe’s strategy in New Jersey in June is a prime

example), and on those occassions when annihilation of the enemy

seemed likely (for example, at Brooklyn, and the chase across the

Jerseys in 1776), the British were foiled more through the exhaustion

of their troops and tactical considerations than a lack of intent or the

commander’s venality and sloth.

Another arena of debate concerns the method Howe chose to get

within striking distance of the city and the risks and benefits involved.

Following his setbacks at the two battles of Trenton and at Princeton,

he had drawn in his horns in New Jersey and relinquished most of

the territory he had once held. From his main bases at Amboy and

Brunswick he tried unsuccessfully during June 1777 to bring the patriot

army, now reduced to about 4,000, to battle. But Washington, ensconced

in solid defensive positions at Morristown and Bound Brook, was not

inclined to take the bait. By 30 June Howe gave up on the cat-and-

mouse game in New Jersey and pulled his army back to New York (and

in consequence delivered his Loyalist supporters to the tender mercies

of their patriot neighbors).

Although many of his officers disagreed, the British commander in

chief ruled out an overland approach across the Jerseys to Philadelphia.

No sane commander, he argued, would want an army strung out over

ninety miles with a highly aggresive enemy chewing on its flanks. So

Howe went back to an earlier plan: an approach to Philadelphia by sea

and via the Chesapeake (which was only later amended to the Delaware

River route). On 9 July he embarked about 13,000 men and left them as

Howe’s officers complained “pent up in the hottest season of the year

in the holds of the vessels”

3

while he waited for news of General John

Burgoyne’s satisfactory progress down from Canada en route to Albany

(which he received on the fifteenth) and Henry Clinton’s arrival from