Stephenson M. Patriot Battles. How the War of Independence Was Fought

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the philadelphia campaign 279

About a mile farther east, off to Greene’s left, column three,

composed of Brigadier General William Smallwood’s 2,000

Marylanders and New Jersey militia, was meant to sweep down the

Old York Road, around the British right wing, and come in from the

rear. Finally, way over on the American right wing (about eight miles

away from Smallwood) Brigadier General John Armstrong was to lead

his Pennsylvania militia down the Ridge Road (parallel to the Skuylkill

River on Armstrong’s right) against the Hessians under Knyphausen,

who were in a commanding position on a rise on the southeastern bank

of the Wissahickon Creek as it runs into the Skuylkill.

If these dispositions were not complicated enough, Washington’s

timetable for attack (to be carried out at night over unfamiliar ground)

was, to put it mildly, optimistic: “Each column to make their dispositions

so as to attack the pickets in their respective fronts precisely at five oClock

with charged bayonets, the columns to move on the attack as soon as

possible. The columns to endeavor to get within two miles of the enemy’s

pickets on their respective fronts by two oClock and halt till four and

make the disposition for attacking the pickets at the time mentioned.”

24

No sooner had Washington’s intricately designed machine moved

off (at 7:00 pm on 3 October) than the wheels began to wobble. Greene’s

group became lost and fell behind the timetable, and the consequence

would have a significant impact on the outcome. At 5:00 am, the hour

for the concerted attack, Washington became uneasy. At 6:00 am on the

fourth Washington’s column made contact with the British pickets on

Mount Airy and began to drive them back down the main road toward

Germantown. The 2nd Battalion of the British light infantry came up

in support, but they too were forced back, which, as an officer recorded,

did not come easily: “We charged them twice till the battalion was so

reduced by killed and wounded that the bugle was sounded to retreat.

Two columns of the enemy had nearly got round our flank. But this

was the first time we had ever retreated from the Americans and it was

with great difficulty that we could get the men to obey our orders.”

25

As the early morning fog grew steadily denser, Lieutenant

Colonel Thomas Musgrave brought up his 40th Foot (he had become

their commanding officer following the death of Lieutenant Colonel

patriot battles 280

James Grant at the battle of Brooklyn), which carried on a skillful

fighting retreat until Musgrave managed to get six companies, about

120 men, inside Cliveden (known in the battle as the “Chew House”),

the handsome and stoutly constructed home of the Loyalist justice

Benjamin Chew. For much of the remainder of the battle the Musgrave

garrison heroically held off repeated American attacks, and fifty-six

patriots would die in that action alone.

During Greene’s approach down the Limekiln Road, Stephen

had veered off to his right, perhaps drawn toward the intense gunfire

at the Chew House. In the swirling fog his command blundered into

the left rear flank of Anthony Wayne’s division, which was part of the

Washington-Sullivan column and at that time closely engaged with

the British right-center near the Market Square, the keystone of the

British positions. In the confusion American fired on American, and

the now decidedly wobbly wheels of Washington’s battle plan started

to fall off. Wayne’s men disengaged and began to withdraw, leaving

Sullivan’s open to attack by the 5th and 55th Foot. Panic began to spread,

exacerbated by the arrival of General Agnew’s division, which was able

to be released from the British left wing only because Armstrong’s pincer

had failed to exert any pressure whatsoever in that quarter. Sullivan’s

men were also running out of ammunition, and men peeled off to the

rear holding open their empty cartridge boxes to show any officer who

might doubt their motives. Although Agnew was killed almost as soon

as he arrived on the scene, his men pushed on, fanning the wildfire

panic that was now racing through the regiments of the Washington-

Sullivan contingent.

Greene, unaware of Wayne and Sullivan’s withdrawal, successfully

penetrated deep into the British right-center, where one of his units, the

9th Virginia of Muhlenberg’s brigade, broke into the Market Square

and began plundering the British camp. While preoccupied with their

loot they were counterattacked by the Guards and the 27th and 28th

Foot and killed or captured to a man. Greene, now isolated, began an

orderly retreat, as Tom Paine, who was in Greene’s division, recorded:

“The retreat was extraordinary. Nobody hurried themselves. Everybody

the philadelphia campaign 281

marched his own pace. The enemy kept a civil distance behind.”

26

Others,

however, remembered a mad panic, “passed the powers of description,

sadness and consternation expressed in every countenance.”

27

Smallwood and Armstrong, out on their respective far-flung flanks,

were left high and dry, their only option to join in the general retreat.

Back they all went the way they had come, all the way back twenty-

four miles to their original camp at Pennypacker’s Mill. In twenty-four

hours they had marched over forty miles and fought a pitched battle

for about four hours. What should have been a demoralized rabble was

in fact extraordinarily buoyant—“high in spirits and appear to wish

ardently for another engagement,” wrote an unidentified officer.

28

Far

from falling from grace, Washington’s stock rose. Adam Stephen, on

the other hand, was cashiered for being drunk and incompetent. He

had been an adversary of Washington’s, in matters military, political,

and commercial, long before the outbreak of war, and his disgrace

would be one of the few satisfactions enjoyed by Washington that day.

Although Douglas Southall Freeman, Washington’s revered

biographer, dismissed the importance of Musgrave’s stand at the

Chew House in influencing the outcome, it does seem to have had

an important impact in several ways. It sucked in a good number of

Washington’s reserves that otherwise would have been engaged in the

main battle; it drew off Stephen’s division, which, in turn, triggered

the friendly fire incident with Wayne’s division and the escalating

panic that followed. Some of Sullivan’s and Wayne’s men were also

spooked by the rumor that the firing behind them indicated that they

were surrounded. Washington, although he had come close to victory,

was robbed by a series of mishaps and miscommunications that in their

accumulation cost him the battle. He was left with that bitterest of dreg

of consolation—“if only . . .”

The British defeat at Saratoga in October 1777 changed everything. It

convinced the French that the odds had shortened on a patriot victory,

patriot battles 282

and they laid down a big bet in the shape of a formal alliance, ratified

by Congress on 4 May 1778. Now Britain would be involved in a

war far outreaching the importance of that being waged against the

thirteen colonies. At stake would be not only its empire but also the

very real possibility of an invasion of Britain itself. The West Indies

were economically crucial to the British economy, and to defend them

against French incursions would involve moving troops and ships from

North America. Sir Henry Clinton, who had succeeded Sir William

Howe as commander in chief in May 1778, was soon called on to send

5,000 men for an expedition against St. Lucia and, consequently, would

be forced to abandon Philadelphia.

On 16 June 1778 the evacuation of the city began, and by the

eighteenth all 10,000 British and Hessian troops had crossed the

Delaware to begin the long hot slog back to New York. Danger lay all

along the route, of course, but for Clinton the overland option seemed

far preferable to having his whole army intercepted on the high seas by

a French fleet. In any event, the thousands of Loyalists who desperately

fought for berths in the limited transports available (a scramble

reminiscent of the evacuation of Saigon in 1975) would have made it

impossible for the British commander to have shipped his army and its

huge baggage and artillery trains back to New York.

Washington, still in his encampment at Valley Forge, was faced

with something of a dilemma. To take on the retreating British column

offered the prospect of a victory that, on the heels of Burgoyne’s

humiliation at Saratoga, almost certainly would have ended the war

instanta. On the other hand, he could simply allow the British to return

unmolested to New York, where they could be bottled up and allowed

to wither without any risk to his own force. Washington, by nature,

invariably favored the more aggressive approach. And although some

historians have claimed that a resounding American defeat at the hands

of Clinton in New Jersey could have jeopardized the whole war, it is

difficult not to agree with Washington that at this stage of the game the

benefits of victory far outweighed the risks.

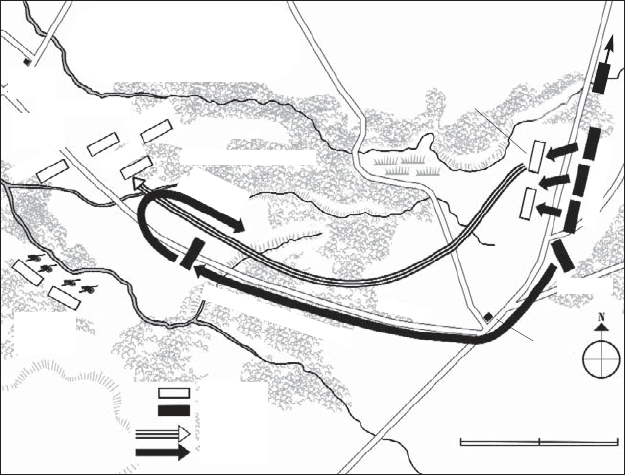

The battle of Monmouth Courthouse that would take place in a

three-mile-long by one-mile-wide corridor of “morasses” and ridges on

the philadelphia campaign 283

Monmouth

Courthouse

28 June 1778

MILES

1

/2 1

Clinton’s

withdrawl

Knyphausen

continues north

Greene’s

Artillery

Lafayette

Stirling

Greene

Cornwallis and Clinton

Clinton

Wayne

L

e

e

’

s

r

e

t

r

e

a

t

Monmouth

Courthouse

Causeway

W

e

s

t

R

a

v

i

n

e

R

a

v

i

n

e

M

i

d

d

l

e

Comb’s Hill

W

e

m

r

o

c

k

B

r

o

o

k

E

a

s

t

R

a

v

i

n

e

C

ORNWALLIS

WASHINGTON

LEE

SECOND PHASE

Final

American

positions

FIRST

PHASE

Freehold

Meeting

House

American

British

American movements

British movements

28 June 1778 would be not only the longest of the whole war but also

the most tactically confused at the individual-unit level. Yet its overall

architecture and dynamics are quite clear.

Clinton’s column, stretched out over twelve miles, lumbered

through the scorching heat. Temperatures would top 100 degrees

Fahrenheit (37 degrees Celsius) on the day of battle. At its head was the

division commanded by the Hessian general Knyphausen. In the rear

was the largest element, commanded by Lord Charles Cornwallis; and

sandwiched between both were the baggage and artillery, dictating the

pace. The column moved slowly through dry sand roads that dragged

on the wheels as effectively as mud. The army was like a great shaggy

bear heading off to its lair with its shanks being constantly nipped and

worried by patriot skirmishers that the beast would occasionally and

ineffectively try to swat.

On 12 June Washington could report his main army strength at

over 13,000, and despite the generally anemic response of most of his

military council to the prospect of a general engagement (Charles Lee,

patriot battles 284

for example, who had been exchanged from captivity in March, was

particularly outspoken against what he saw as a disastrously overambitious

attack, calling it “criminal”), Washington felt emboldened to test the

British positions with a strong advance probe. He initially offered this

assignment to Lee as the highest-ranking general under the commander

in chief. Lee, perhaps bridling at what he saw as Washington’s favoritism

of the young Lafayette, refused it with a patronizing nod to his youthful

rival. This refusal of the command is interesting because it is usually

seen as the crabby elder soldier’s condescension to a younger contender

as being “a more proper business for a young volunteering general.”

But perhaps Lee had grounds for his umbrage.

Lafayette has been described as “the logical candidate.”

29

Washington was now placing his trust in him, but because Lafayette

was only twenty years old in June 1778 and had very little combat or

command experience, one has to doubt his credentials in the face of

a slew of other contenders. And although a biographer, Harlow Giles

Unger, describes Lafayette before the battle of Monmouth as “the next-

highest-ranking combat officer” (after Lee),

30

Washington’s favoring of

the young man and his clumsy handling of Lee show a leader whose

command effectiveness had been compromised by equivocation.

Washington held Lee in awe, as did many in the patriot officer corps,

and his reward was to be the butt of Lee’s sneering. When Washington

was struggling for survival during the retreat across the Jerseys in 1776,

Lee almost contemptuously disregarded his pleas for reinforcement.

When Lee was exchanged from captivity in March 1778, Washington put

on a lavish show of welcome that Lee treated ungraciously. Washington

would have had to be a saint not to have harbored some resentment

at the Englishman’s hubris. Where as Charles Lee was a difficult man

to like, unkempt, foulmouthed, and generally bizarre, Lafayette was

charming and amiable, and showed an almost filial affection toward his

commander in chief. Whatever the psychological shoals and riptides,

Washington’s vacillations and maladroit attempts to “manage” the two

men would be disastrous.

When the size of the advance guard became a substantial 4,000-plus,

Lee about-faced and asserted his right by seniority to its command (he

the philadelphia campaign 285

would be “disgraced” otherwise, he said), and Washington acquiesced,

putting aside the uncomfortable fact that Lee vehemently opposed

the commander in chief’s whole strategy. Reflecting the confusion he

had created, as well perhaps as his reluctance to tackle Lee head-on,

Washington’s orders were vague and contradictory. Lee was to bring

on “an engagement or attack the enemy as soon as possible” but yet not

allow himself to become embroiled.

31

As to the tactical means, that was

left up to Lee. The problem was Lee also had no idea what he intended

to do, telling his commanders at 5:00 pm on the twenty-seventh that

he could make no plan because he was ignorant of the terrain and the

enemy’s strength.

Although Lee had been ordered to reconnoiter during the early

hours of the twenty-eighth, he neglected to do so until around 6:00

am, by which time Clinton had already sent off Knyphausen and

the baggage on the northeast road toward Middletown, and shortly

thereafter followed him with Cornwallis’s division. A rear guard was

left at Monmouth Meeting House, and it was this that whetted Lee’s

appetite. Lee’s disposition of his forces, however, was chaotic. They were

“shifted about in kaleidoscopic arrangements and rearrangements”

32

and served only to alert Clinton and Cornwallis, who, like an enraged

bear, swung around and turned on their attackers. It was a very big bear.

Cornwallis’s command (which Clinton accompanied) was composed

of the brigade of Guards; both battalions of British grenadiers; all the

Hessian grenadiers; both battalions of the British light infantry; the

3rd, 4th, and 5th infantry brigades; the 16th Light Dragoons; and John

Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers, the premier Loyalist regiment.

It was little wonder that Lee’s command began to fall apart, and

one of the ironies, given the complications of the Washington-Lee-

Lafayette triangle, was that it was probably Lafayette’s shifting of

position (unauthorized by Lee) which was mistakenly interpreted as

a retreat and triggered a panicked response in other regiments.

33

In no

time Lee found himself swept up in a full-scale retreat, his men flowing

back due west toward their starting positions to seek the refuge of the

rest of the army some five miles back. A battle that Washington had

always intended (despite his more pusillanimous advisers) to be highly

patriot battles 286

aggressive had been turned on its head. The hunters were now the

hunted.

With chivalric heroism, legend has it, Washington rode among the

retreating and defeated, astride his great white charger, rallying and

returning them to the fight by the sheer magnetism of his personality. To

add to the irony of Lafayette’s contribution to Lee’s discombobulation,

one of the primary contributors to the Washington legend (some might

even say deification) was none other than Lafayette himself. In his

Mémoires, published in 1837, three years after his death, he remembered:

“General Washington was never greater in battle than in this action. His

presence stopped the retreat; his strategy secured the victory. His stately

appearance on horseback, his calm, dignified courage, tinged only

slightly by the anger caused by the unfortunate incident in the morning,

provoked a wave of enthusiasm among the troops.”

34

Lee was stopped by

Washington and given, by popular account, a scorching public tongue-

lashing, which reduced the little bombast to spluttering incoherence.

(Washington would later deny using any “singular expressions.”)

Heroic intervention may well have played its part, but as

Washington created his defensive line on the high ground above the

western “morass,” it was something altogether less romantic that held

the army together: von Steuben’s long training sessions of formation

drill and volley fire during the Valley Forge winter. (Alexander

Hamilton would later record that he had never understood the point

of military discipline until he saw von Steuben’s “reformed” army at

work that afternoon.) At first against Stirling on the American left

wing, then against Greene on the right and Washington in the center,

the British and Hessians threw in attack after attack, which, although

executed with extraordinary commitment and sacrifice, withered under

disciplined musketry and artillery fire. The patriot lines would not be

broken.

As evening drew on, this, the longest battle of the war, literally

burned itself out, both armies exhausted by the unrelenting heat.

The British recorded “3 sergeants, 56 rank and file died with fatigue

[sunstroke].” The Americans lost thirty-six to the same cause. A standoff

artillery duel was all either side could muster. Washington, aggressive

the philadelphia campaign 287

as always, was not prepared to accept the failure of his original intention

and ordered Brigadier General William Woodford’s Virginians and

Clark’s North Carolinians to counterattack on both British flanks. The

fast-closing night, however, put an end to any further action, and at

midnight the wily Clinton slipped away and rejoined Knyphausen. A

week later he and his army were safely in New York.

The battle of Monmouth, if reduced to a description of unit

movements, is confusing and frustrating because many of the sources

are contradictory. But there is a fascinating, if conjectural, connective

vein that runs though it: the idea of betrayal. If Lee had betrayed

Washington’s trust in the past (he may also have more literally betrayed

the American cause while in British captivity), Washington certainly had

his revenge by battle’s end. A cynic might conclude that Washington’s

special relationship with Lafayette, his muddying of the command

structure, his vague instructions, and Lafayette’s own conduct during

the first phase of the battle, “set up” the unfortunate and unsympathetic

Lee for failure: a failure for which he would be, conveniently, the

scapegoat.

Lee’s own temperament could not have been more useful to

Washington. Lee simply self-destructed under the disgrace, insulted

the commander in chief in writing, and was thrown out of the army.

One last irony, though, is that many of the officers—both American and

British—present during the first phase attested that Lee’s conduct in

the face of an overwhelming British force was appropriate and carried

out with military professionalism. For Washington it must have been

an irony sweetly to be savored.

18

The Saratoga Campaign

FREEMAN’S FARM, 19 SEPTEMBER 1777;

AND BEMIS HEIGHTS, 7 OCTOBER 1777

M

ajor General John Burgoyne, commander in chief of the

royal forces about to invade America from Canada, was, in

his other life, a successful playwright. As he set off from St.

Johns in June 1777 he little knew that he would unwittingly rehearse

the whole of the British experience of the War of Independence in

miniature. It would be a play in three acts: a triumphant beginning; a

grim middle; and a pathetic finale. The story line had seemed strong

enough at first, but someone rewrote it halfway through and then

everything began to go wrong. The scenery proved problematic, the

supporting cast decamped for a better-paying show, and the necessary

props either fell apart or failed to appear on cue. The author, who was

also the director and principal actor, remained steadfast that he’d written

a smash, if only the backers had supported him as they had promised.

He was also, in the spirit of his age and class, a chancer, described

by Arthur Lee, the special agent for Massachusetts in London, as “an

abandoned & notorious gambler.”

1

On the Christmas Day before he

left to take command of the invading force in Canada, Burgoyne had

wagered fifty guineas with his good friend (although a bitter opponent