Stephenson M. Patriot Battles. How the War of Independence Was Fought

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a vaunting ambition 229

side of the barrier. Working from room to room, they drove out the

Americans at the point of the bayonet. At the same time Carleton sent

500 men under Captain George Laws to loop around, come up behind

Morgan, and bottle him up. Although Morgan urged a counterattack

and breakout against the British troops now blocking his only escape, he

was overruled by his fellow officers and “Arnold’s subordinates agreed

to surrender.”

17

Morgan, cornered and snarling in defiance, refused to

surrender to the British and would offer his sword only to a French

priest he spotted nearby. The number of Americans captured (426), the

high ratio of American dead to wounded (62:42),

18

and the small loss of

the defenders (about five dead) were sanguinary reminders of the heavy

price brave men paid for a commander’s tactical naïveté.

Although reinforced periodically through the early months of 1776,

the American besiegers were ravaged by smallpox and undermined by

lack of money. Carleton, on the other hand, kept himself snugly and

safely ensconced behind his stout walls and bastions as the morale of

his enemy disintegrated. As the ice ceded the St. Lawrence to spring,

British warships, carrying 200 men of the 29th Foot and a detachment

of marines, made their way to the city, and almost immediately a strong

sortie from Quebec had the patriots in a full-fledged and panicked

retreat westward down the St. Lawrence and then over the river to the

relative safety of Sorel.

15

“We Expect Bloody Work”

BROOKLYN, 22–29 AUGUST 1776

C

harles Lee declared it was hopeless. Washington’s bumptiously

self-regarding second-in-command had been sent south from

Boston to oversee the defenses of New York and immediately

declared to Washington that the city was indefensible because it was

“so circled with deep navigable water.” Some others, like John Jay, the

New York delegate to the Continental Congress, shared Lee’s general

pessimism and offered a very radical solution indeed. Burn New York

City, scorch Long Island, and establish the army in the natural fortress of

the Hudson Highlands. Washington, and Congress, saw it differently.

The city was, in Washington’s estimation, “a post of infinite importance

both to them and us.” Commanding the mouth of the Hudson, it was a

springboard for naval actions north and south and therefore of immense

strategic potential. Washington was determined to do his damnedest to

deny it to the British.

For a man who saw the importance of the “deep navigable water”

surrounding Manhattan, Lee was peculiarly blind to the possibilities

of at least attempting to deny the British navy easy access to it. During

February and March 1776 he busied himself with strengthening the

defenses within the city. For example, all roads leading to the Hudson

River were barricaded, batteries were installed down on the lower east

“we expect bloody work” 231

side, and the fortress of St. George at Battery Point was reinforced. He

built a string of redoubts across the island at Grand Street, protected

the two bridges—Kingsbridge and Freebridge—which connected

the mainland at the northern end of Manhattan, and, most important,

fortified Brooklyn Heights, which dominated the city from the Long

Island side. In order to deny the British access to the East River from

the Sound, batteries were established on Montresors Island (today’s

Randalls Island). To guard the southern entrance to the East River,

Horn’s Hook, a small peninsula just south of Brooklyn Heights, and

Governors Island, which sat practically in the mouth of the East River,

were fortified.

Lee and a sequence of other American commanders (Lord Stirling,

Nathanael Greene, and Israel Putnam) who succeeded him when he was

sent down to South Carolina to take charge of the defense of Charleston

neglected, despite congressional resolutions, to place batteries on the

two choke points through which shipping had to pass to get into New

York Harbor. The first was Sandy Hook, a slender peninsula jutting up

from the Jersey shore that commanded the sandbars that lay across the

threshold to the Lower Bay. At high tide shipping could pass over the

bars. The second was the Narrows, a mile-wide channel between the

western tip of Long Island and the eastern edge of Staten Island that led

into the Upper Bay. Shore batteries placed here would have forced the

British to run a gauntlet that could have proved costly indeed. (Colonel

William Douglas, with somewhat more foresight, predicted, “It will

be in vain for us to exspet [sic] to Keep the Shiping out of the North

[Hudson] River unless we can fortify at the Narrows.”)

1

Nevertheless,

Lord Stirling expressed a supreme confidence in the defensive network

that had been created during the spring and summer, writing to

Washington that there was “little to fear from General Howe, should

he attempt anything in this quarter,” and adding for good measure, “I

could wish General Howe would come here in preference to any other

spot in America.”

2

When the British did come, they did so with a force of

unprecedented size: the largest Britain had ever assembled for an

overseas expedition. On 25 June Howe and 9,000 troops in the first

patriot battles 232

contingent arrived. His 130-ship convoy from Halifax moved through

the Narrows: “Some of the ships [were] within 7 or 800 yards of Long

Island,” commented a British officer. “We observed a good many of

the Rebels in motion on Shore. They fired musquetry at the nearest

ships without effect . . . Luckily for us the Rebels had no cannon here

or we must have suffered a good deal.”

3

They landed on Staten Island

untroubled by any American resistance. General Howe was followed,

over the next two weeks, by his older brother, Admiral William “Black

Dick” Howe, with 13,000 men and 150 ships; Sir Peter Parker returned

with another 3,000 men from South Carolina, and Commodore William

Hotham from England (transporting 1,000 Guards and 7,800 German

mercenaries under Philip von Heister). When it was all assembled, the

British expeditionary force numbered 32,000 soldiers, 10,000 sailors,

2,000 marines, and 400 transports.

Washington, by comparison, had initially brought somewhere

in the region of 10,000 Continentals. In May Congress had voted to

mobilize 23,000 militia, of whom 14,000 were earmarked for the New

York defenses. (General Howe wildly overestimated the American

strength at 35,000, a miscalculation that may well have had a bearing on

the eventual outcome of the battle.) But as with many of these grandiose

plans, the result did not quite match the intention. For one thing, the

squalor within the city that resulted from too many men crammed into

too small an area resulted in debilitating disease. The city’s water supply

quickly became contaminated, and the “camp disorder” (typhoid fever)

and “bloody flux” (dysentery) took their toll. One of the victims was

Nathanael Greene, who was rendered hors de combat for the whole

of the forthcoming battle—a grievous blow to Washington’s command

structure.

Where would Howe strike? The diversity of the patriot

preparations, aimed at countering possible attacks on the lower west side

of Manhattan, or higher up around what is now 125th Street, or perhaps

coming down the Sound to land at Kingsbridge on the Harlem River,

gives some idea of Washington’s dilemma and Howe’s opportunity.

Henry Clinton, as he had at Bunker’s Hill, advocated a sweeping

outflanking maneuver, landing midway up on Manhattan and bagging

“we expect bloody work” 233

Washington and most of his army. Howe, though, held fast to his belief

that the capture of Brooklyn Heights was the first priority. Although,

given his enormous superiority in men, ships, and armament, it does

not seem entirely unrealistic to wonder why an attack on the Heights

coordinated with the broadly outflanking movement advocated by

Clinton was ruled out. Washington’s own agonized indecision, even

after the British had landed on Long Island, reflects that he at least

believed a multipronged attack a possibility and, given the vulnerability

of his defensive position, a sound strategy.

With or without an outflanking strategy Howe had good reasons

for attacking Brooklyn Heights. First, the city itself was heavily

defended. Washington’s adjutant general, Joseph Reed, wrote to his

wife, “The city is now so strong that in the present temper of our men,

the enemy would lose half their army in attempting to take it.”

4

Second,

he would have no security in New York without having captured the

Heights. Third, Long Island was a highly productive agricultural

area that would reduce his dependency on supplies shipped in from

Britain. Fourth, it was a Loyalist stronghold. Fifth, it offered a long,

proximate, and, as it turned out, undefended coastline. Sixth, he had a

highly effective intelligence network of Loyalist contacts, and Clinton

(unlike Washington, Putnam, and Sullivan, the primary American

commanders in the battle) knew the terrain well. He had, after all, been

born and raised in New York City when his father was governor, and

had carried out detailed reconnaissances relatively recently.

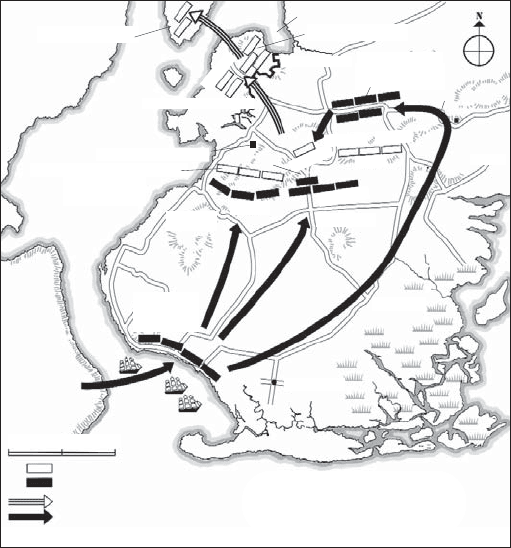

At 9:00 am on Thursday, 22 August, Howe landed an advance corps

of 4,000 light infantry and grenadiers under the command of Henry

Clinton and Charles Cornwallis at Gravesend Bay on the southwestern

tip of Long Island, about seven miles south of the main American

fortifications on the Brooklyn peninsula. Specialized landing craft

(ramp-fronted, not unlike the LCTs used in World War II) deposited

them on the beach and then returned to an armada of transports already

anchored off Gravesend to pick up 11,000 more troops, cannon, wagons,

and cavalry. By noon on the twenty-second Howe had approximately

15,000 men ashore—with more to follow.

The American defenses that Howe would have to reduce were

patriot battles 234

planned as a “collapsible buffer.” The inner fortifications consisted

of a necklace of redoubts and entrenchments that ran north-to-south

across the neck of the Brooklyn peninsula, from Wallabout Bay in the

north sweeping down to the marshes of the Gowanus Creek. Beyond

them, farther inland, was the steep escarpment of the Gowanus Ridge

(sometimes called the Heights of Guam or Prospect Heights), which

ran west-to-east from Gravesend across to Jamaica, roughly parallel

with the coast on which the British had landed. It was heavily wooded,

perfectly tailored for the irregular, Indian-style tactics suited to American

troops, and intersected by only a few passes that could be effectively

defended by relatively few men. A contemporary wrote, “To an enemy

advancing from below [from the south where the British were camped

on the coastal flats], it presented a continuous barrier, a huge natural

abattis [sic], impassable to artillery, where with proportionate numbers

a successful defence could be sustained.”

5

From the point of view of the British, sitting down at Gravesend,

there were five options. On their left was the coastal road leading up to

Gowanus Creek and the Brooklyn fortifications; the next most westerly

pass was Martense Lane Pass; then came Flatbush and Bedford passes;

and then, far over at the eastern extremity of the Gowanus Ridge was

Jamaica Pass, six miles away. Sullivan (who had taken over from the

incapacitated Greene) was in charge of the outer defenses on the ridge.

He placed 800 men in each of the first three passes but had not defended

Jamaica Pass. It seemed so far away and such a long shot for the British

that he ruled it out as a threat. However, he did send a five-man mounted

scouting party out toward Jamaica Pass—at his own expense, as he later

bitterly complained—but it was to prove a useless precaution. (Some

weeks earlier Washington had rejected the services of 400 Connecticut

cavalry because he could not feed their mounts—a costly mistake, as it

turned out.)

Henry Clinton may have been a world-class whiner, but he was also

a first-class strategist. (It was a combination that must have given Howe

as much pleasure as a sharp stone in his shoe, or as Clinton admitted,

with deadpan understatement, “My zeal may perhaps on these occasions

have carried me so far as to be at times thought troublesome.”) Between

“we expect bloody work” 235

22 and 26 August Clinton concocted a plan of exceptional boldness: a

huge flanking sweep right around the eastern extremity of the Gowanus

Heights, which, by use of the Jamaica Pass, would bring him up behind

Sullivan on the Heights and cut Sullivan off from retreat to the main

American fortifications at Brooklyn.

While the outflanking maneuver was in motion, Clinton further

proposed that Major General James Grant would move up the coastal

road and engage the American right wing. Simultaneously, the Hessians

would move against the American center at Flatbush. It was important

that these two supporting moves did not push too far. They were to be,

initially, holding maneuvers designed to divert and engage American

forces while Clinton, Cornwallis, and Howe completed their encirclement.

Grant and the Hessians were to be the anvil to Clinton’s hammer. Once

the flanking force was in position, it would fire two guns to signal Grant

and the Hessians that everything was set for the battle proper.

Brooklyn

22–29 August 1776

American

British

American movements

British movements

MILES 1 2

Jamaica Pass

Flatbush Pass

Martense

Lane Pass

Brooklyn

N

EW JERSEY

LONG

S

I

SLAND

F PUTNAM

F GREENE FT. BOX

Upper Bay

Lower Bay

Jamaica Bay

East R.

Lower Manhattan

Brooklyn Heights

Governors

Island

Gravesend

Flatlands

Flatbush

Grant

Stirling, Smallwood, Haslet

Parsons, Atlee,

Huntington

Hessians

Chester

HOWE/CLINTON

/C

Sullivan

Putnam

M

iles

Wyllys

27 Aug., 8:00 AM

K

i

n

g

’

s

H

i

g

h

w

a

y

British land

9:00

AM

22 Aug.

A

m

e

r

i

c

a

n

r

e

t

r

e

a

t

H

o

w

e

’

s

n

i

g

h

t

m

a

r

c

h

,

2

6

/

2

7

A

u

g

.

F

l

a

t

b

u

s

h

A

v

e

.

ISLAND

Howard’s

Tavern

TATEN

ORT

ORT

Wallabout Bay

Vecht-Cortelyou House

ORNWALLIS

patriot battles 236

It was a brilliantly audacious plan, and Clinton was sure, given his

experiences with Howe at Bunker’s Hill and the earlier rejection of his

plan to land a force on mid-Manhattan, that Howe would reject it: “In

all the opinions he [Howe] ever gave me, [he] did not expect any good

from the move.”

6

Sir William Erskine offered to take Clinton’s proposal

to Howe (itself a reflection of the strained relationship). The Loyalist

Oliver De Lancey, who also knew the terrain intimately, supported

Clinton’s plan, and Howe, teeth clenched no doubt, accepted it.

On Monday, 26 August, at 9:00 pm, with the tents of the main camp

left standing and cooking fires burning, Clinton led the vanguard of

the British flanking force, consisting of dragoons and light infantry,

followed later by Cornwallis, Lord Percy (of Concord fame), and

Howe, up the Kings Highway toward New Lots and the Jamaica

Pass. In all there were 10,000 men in a column two miles long moving

with the strictest regard for silence, first on the highway but soon on a

much less conspicuous cart track. Units of the light infantry flanked the

column with orders to detain anyone who might give the game away.

However, it is almost impossible to move so large a force completely

undetected. Colonel Daniel Brodhead complained that the American

high command was detached and unresponsive: “Gen’ls Putnam and

Sullivan and others came to our camp which was to the left of all the

other posts and proceeded to reconnoiter the enemie’s lines to the right,

when from the movements of the enemy they might plainly discover

they were advancing towards Jamaica, and extending their lines to the

left so as to march round us.”

7

Colonel Samuel Miles, stationed between the Bedford and Jamaica

passes with two battalions of riflemen, later insisted that he had

forewarned Sullivan of Howe’s intentions: “I was convinced when the

[British] army moved that Gen’l Howe would fall into the Jamaica road,

and I hoped there were troops there to watch them. Notwithstanding

this information, which indeed he might have obtained from his own

observation, if he had attended to his duty as a general ought to have

done, no steps were taken.”

8

The only troops that were watching, the

five-man vedette so expensively procured by Sullivan, were captured

easily and noiselessly and by 2:00 am the whole British column was in

“we expect bloody work” 237

place at the entrance to Jamaica Pass. Miles would be captured after a

desperate but futile engagement with the rear of the British column.

Back on the coastal road, Grant began his move just before midnight,

having allowed Howe’s column a three-hour start. With 5,000 infantry

and 2,000 marines he marched quietly up the Shore Road and about 1:00

am engaged the picket of Colonel Atlee’s Pennsylvania musketeers. By

3:00 am Israel Putnam, Washington’s designated overall commander on

Long Island, made a rare appearance outside the confines of the interior

lines at Brooklyn to order Brigadier General Lord Stirling of Sullivan’s

division south to counter Grant’s advance, which was generally taken to

be the main British thrust: “I fully expected, as did most of my officers,

that the strength of the British army was advancing in this quarter to

our lines,” wrote Stirling later.

Available to Stirling were two regiments that would fight them-

selves into legend, here and throughout the war: William Smallwood’s

Marylanders (the “Dandy Fifth”) and John Haslet’s Delawares. Both

regiments were at this time commanded by their majors, Mordecai Gist

and Thomas McDonough respectively, the colonels being detained in

New York City on court-martial duty, an astonishing piece of bureau

-

cratic nonsense, given the circumstances. Washington too was enmeshed

in the spider’s web of administration that prevented his full involve

-

ment in the battle.

Stirling took six companies of the Marylanders and Delawares,

together with another 400 men sent over from the center by Sullivan,

and hurried down to reinforce the embattled Atlee. Stirling’s total

strength was now about 2,000 against Grant’s 9,000. He drew his main

force up on Blockje’s Hill, facing the British, with Atlee on his right

nearest the coast and a detachment of Marylanders pushed forward on

his left. It was a classic formation: the inverted V, or kettle as Frederick

the Great had termed it. The arms of the V opened toward the enemy

in a warm welcome, a Venus flytrap, into which, hopefully, the British

would enter. There was a problem, however. The British did not enter.

In fact, it was they who glued Stirling to their flypaper. Standing off on

a facing rise, Grant bombarded Stirling’s men, who stood stoically in

rank in the “true English taste,” as one of them ironically recorded, and

patriot battles 238

took a pounding from very early in the morning to midday: “Both the

balls and shells flew very fast, now and then taking off a head. Our men

stood it amazingly well, not even one showed a disposition to shrink.”

9

The Americans could not advance against a numerically superior Grant;

nor could they retreat until overwhelmed. Grant did not overwhelm.

He knew what he had to do: keep Stirling in place.

10

Around 7:00 am the Highlanders and Hessians under Philip von

Heister and Carl von Donop engaged Sullivan’s men at the edge of the

wooded escarpment at Flatbush. Again, it was a holding action rather

than an all-out drive.

At 8:00 am Howe’s force, now safely through Jamaica Pass and at

Bedford village, fired their signal cannon.

11

Relieved of any need for

secrecy, Cornwallis and his grenadiers continued on to sweep down

on Stirling’s rear. Clinton’s light troops and dragoons peeled off south

down the road to Flatbush, the light infantry fanning out into the

woods on either side of the road to descend on Sullivan’s men, who

were preoccupied with the Hessians and Highlanders on their front.

The hammer was about to strike the anvil.

The Hessian jägers—expert riflemen deployed as skirmishers—

and uniform ranks of the Scots and German infantry, “with martial

music sounding and colors flying,” broke through Flatbush Pass and

began to move up through the woods, flushing out the enemy at the

point of the bayonet. It was, in the French term, a battue: the driving of

game to the guns. As the Americans fled out of the woods in a desperate

attempt to reach their interior lines, they had to cross an intervening

plain, and it was here that the British dragoons swept down while the

light infantry, combining with the Hessians and Scots, systematically

corralled and destroyed groups of patriots in the woods. An officer of

Fraser’s Highlanders (71st Foot) reveled in the slaughter.

Rejoice . . . that we have given the Rebels a d. . . . d crush . . . The

Hessians and our brave Highlanders gave no quarter, and it was a

fine sight to see with what alacrity they dispatched the Rebels with

their bayonets after we had surrounded them so they could not

resist . . . It was a glorious achievement . . . and will immortalize