Snoman R. Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART 3

Mixing & Promotion

384

While many older engineers still stand by this view, it means absolutely noth-

ing to the dance musician since a proportionate amount of the timbres used

will be synthetic anyway. Thus, apart from using EQ to help instruments sit

together and create space within a mix, EQ should also be seen as a way of cre-

atively distorting timbres.

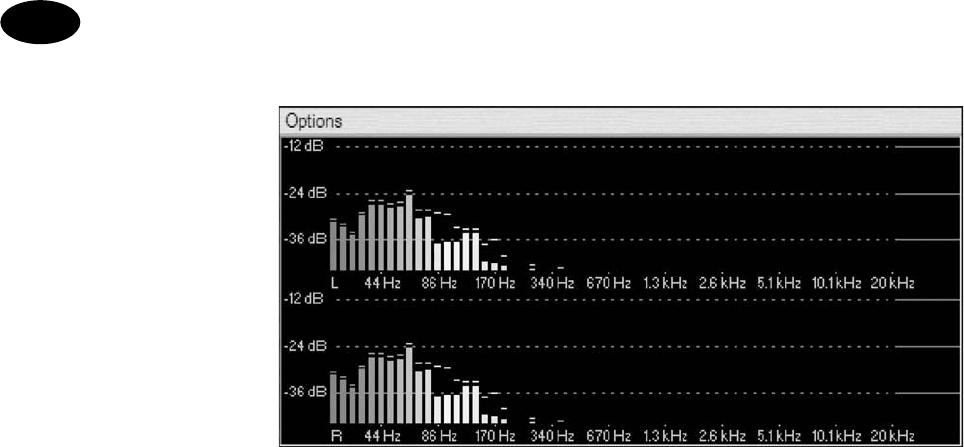

Since EQ is essentially a fi lter, it can be used to reduce certain frequencies of a

sound, which will have the immediate effect of increasing the frequencies that

have not been touched. As an example of this, we’ll use a spectral analyzer to

examine the frequency content of the bass sound that was created for the house

track ( Figure 19.8 ).

Notice how there are a number of peaks in the timbre. If you were to listen to

this sound, you would primarily hear these four loudest frequencies. However,

using EQ creatively you can turn down these peaks to hear more of the entire

frequency spectrum of the bass. It then becomes much more harmonically

complex and can sustain repeated listening because the closer you listen to

it the more you can hear. Making a sound appear as complex as possible by

reducing the peaks is a common practice for many big-name producers. This

could be further accentuated by applying small EQ boosting to the lower peaks

of a sound.

On the other hand, simple ones can work as well as complex ones. This can

be accomplished by cutting all but these four peaks. This cutting can also

offer another advantage: as it is unlikely that you would be able to perceive the

lowest frequencies (harmonics) contained in the sound, there is little need to

leave them in; by removing them you would make more room for instruments

in the mix .

You shouldn’t simply grab a pot and start creatively boosting aimlessly since

you need to consider the loudspeaker system that the mix is to be played back

on. All loudspeaker systems have a limited frequency response and produce

FIGURE 19.8

A spectral analysis of

the house bass sound

Mixing

CHAPTER 19

385

more energy in the mid-range than anywhere else. This means that if you

decide to become ‘creative ’ on the bass or mid-range, you could end up increas-

ing energy that the speaker cannot reproduce faithfully, resulting in an over-

zealous or muddy mid-range, or worse still, a quieter mix overall!

The main use for EQ within mixing, however, is to prevent any frequency masking

between instruments. As touched upon in Chapter 1, the fundamental and subse-

quent harmonics contribute to making any sound what it is, but if two timbres

of similar frequencies are mixed together, some of the harmonics are ‘masked’,

resulting in the instruments sounding different in the mix than in isolation.

While this can have its uses in sound design (hocketing, layering etc.), dur-

ing mixing it can cause serious problems since not only is it impossible to mix

sounds that you can’t hear, the frequencies that mix together can make both

sounds lose their overall structure, become indistinct or, worse still, the confl ic-

tion will result in unwanted gain increases.

Naturally, knowing if you have a problem with frequency masking is the fi rst

step towards curing it; so if you’re unsure whether some instruments are being

masked, you can check by raising the volume of every track to unity gain and

then panning each track in turn to the left of the stereo fi eld and then to right. If

you hear the sound moving from the left speaker through the centre of the mix

and then off to the right, it’s unlikely that there are any confl icts. This, however,

is about the only generalization you can make for mixing. The rest is entirely

up to your own artistic preferences. Because of this, what follows can only be a

very rough guide to EQ and to the frequencies that you may need to adjust to

avoid any masking problems. As such, they are open to your own interpretations

because, after all, it’s your mix and only you know how you want it to sound.

Drums

DRUM KICK

A typical dance drum kick consists of two major components: the attack and

the low-frequency impact. The attack usually resides around 3 –6 kHz and the

low-end impact resides between 40 and 120 Hz. If the kick seems very low

without a prominent attack stage, then it’s worthwhile setting a very high Q

and a large gain reduction to create a notch fi lter. Once created, use the fre-

quency control to sweep around 3 –6 kHz and place a cut just below the attack,

as this has the effect of increasing the frequencies located directly above.

If this approach doesn’t produce results, set a very thin Q as before, but this

time apply 5 dB of gain and sweep the frequencies again to see if this helps it

pull out of the mix. Taking this latter approach can push the track into distor-

tion, so remember to reduce the gain of the channel if necessary.

If the kick’s attack is prominent but it doesn’t seem to have any ‘punch’, the

low-frequency energy may be missing. You can try small gain boosts of around

40–120 Hz but this will rarely produce the timbre. The problem more likely

resides with your choice of drum timbre. A fast attack on a compressor may

PART 3

Mixing & Promotion

386

help to introduce more punch as it’ll clamp down on the transient, reducing

the high-frequency content. But this could change the perception of the mix,

so it may be more prudent to replace the kick with a more signifi cant timbre.

SNARE DRUM

Generally, snare drums contain plenty of energy at low frequencies that can often

cloud a mix and are not necessary; so the fi rst step should be to employ a shelv-

ing (or high-pass) fi lter to remove all the frequency content below 150 Hz.

The ‘snap’ of most snares usually resides around 2 –10 kHz, while the main

body can reside anywhere between 400 Hz and 1 kHz. Applying cuts or boosts

and sweeping between these ranges should help you fi nd the elements that you

need to bring out or remove but, roughly speaking, cuts at 400 and 800 Hz

will help it sit better while a small decibel boost (or a notch cut before) at 8 or

10 kHz will help to brighten its ‘snap’.

HI-HATS AND CYMBALS

Obviously, these instruments contain very little low-end information that’s of

any use and, if left in, can cloud some of the mid-range. Consequently, they

benefi t from a high-pass fi lter to remove all the frequencies below 300 Hz.

Typically, the presence of these instruments lies between 1 and 6 kHz while the

brightness can reside as high as 8 –12 kHz. A shelving fi lter set to boost all fre-

quencies above 8 kHz can bring out the brightness but it’s advisable to roll off

all frequencies above 15 kHz at the same time to prevent any hiss from break-

ing through into the track. If there is a lack of presence, then small decibel

boosts with a Q of about an octave at 600 Hz should add some presence.

TOMS AND CONGAS

Both these instruments have frequencies as low as 100 Hz but are not required

for us to recognize the sound and, if left, can cloud the low and low mids;

thus, it’s advisable to shelve off all frequencies below 200 Hz. They should not

require any boosts in the mix as they rarely play such a large part in a loop but

a Q of approximately 1/2 of an octave applied between 300 and 800 Hz can

often increase the higher end, making them appear more signifi cant.

Bass

Bass is the most diffi cult instrument to fi t into any dance mix since its interac-

tion with the kick drum produces much of the essential groove – but it can be

fraught with problems.

The main problems with mixing bass can derive from the choice of timbres

and the arrangement of the mix. While dance music is, by its nature, loud

and ‘in your face ’, this is not attributed to using big, exuberant, harmonically

rich sounds throughout. As we’ve touched upon, our minds can only work in

contrast, so for one sound to appear big, the rest should be smaller. Of course,

Mixing

CHAPTER 19

387

this presents a problem if you’re working with a large kick and large bass, as

the two occupy similar frequencies which can result in a muddied bottom end.

This can be particularly evident if the bass notes are quite long as there will

be little or no low-frequency ‘silence’ between the bass and the kicks, mak-

ing it diffi cult for the listener to perceive a difference between the two sounds.

Consequently, if the genre requires a huge, deep bass timbre, the kick should

be made tighter by rolling off some of the confl icting lower frequencies and

the higher frequency elements should be boosted with EQ to make it appear

more ‘snappy ’. Alternatively, if the kick should be felt in the chest, the bass can

be made lighter by rolling off the confl icting lower frequencies and boosting

the higher elements.

Naturally, there will be occasions whereby you need both heavy kick and bass

elements in the mix, and in this instance, the arrangement should be confi g-

ured so that the bass and the kick do not occur at the same point in time. In

fact, most genres of dance will employ this technique by offsetting the bass so

that it occurs on the offbeat. For instance, trance music almost always uses a

4/4 kick pattern with the bass sat in between each kick on the eighth of the bar.

If this isn’t a feasible solution and both bass and kick must sit on the same beat,

then you will have to resort to aggressive EQ adjustments on the bass. Similar

to most instruments in dance music, we have no expectations of how a bass

should actually sound, so if it’s overlapping with the kick making for a muddy

bottom end, you shouldn’t be afraid to make some forceful tonal adjustments.

Typically for synthetic instruments, small decibel boosts with a thin Q at

60–80 Hz will often fatten up a wimpy bass that’s hiding behind the kick. If

the bass still appears weak after these boosts, you should look towards replac-

ing the timbre; it’s a dangerous practice to boost frequencies below these as it’s

impossible to accurately judge frequencies any lower on the near-fi elds. In fact,

for accurate playback on most hi-fi systems it’s prudent to use a shelving fi lter

to roll off all frequencies below 60 Hz.

Of course, this isn’t much help if you’re planning on releasing a mix on vinyl

for club play as many PA systems will produce energy as low as 30 Hz. If this

is the case, you should continue to mix the bass but avoid boosting or cutting

anything below 40 Hz. This should be left to the mastering engineer who will

be able to accurately judge just how much low-end presence is required. As a

very rough guide for theoretical purposes alone, a graphic equalizer set to ⫺ 6 dB

at around 20 Hz, gently sloping upwards to 0 dB at 90 Hz, can sometimes prove

suffi cient enough for club play.

If the problem is that the bass has no punch, then a Q of approximately half of

an octave with a small cut or boost and sweeping the frequency range between

120 and 180 Hz may increase the punch to help it to pull through the kick.

Alternatively, small boosts of half of an octave at 200 –300 Hz may pronounce

the rasp, helping it to become more defi nable in the mix. Notably, in some mixes

the highest frequencies of the rasp may begin to confl ict with the mid-range

PART 3

Mixing & Promotion

388

instruments, and if this is the case then it’s prudent to employ a shelving fi lter

to remove the confl icting higher frequencies.

Provided that the bass frequencies are not creating a confl ict with the kick,

another common problem is the volume in the mix. While the bass timbre

may sound fi ne, there may not be enough volume to allow it to pull to the

front of the mix. The best way to overcome this is to introduce small amounts

of controlled distortion, but rather than reach for the atypical distortion unit,

it’s much better to use an amp or speaker simulator.

Amp simulators are designed to emulate the response of a typical cabinet,

so they roll off the higher frequency elements that are otherwise introduced

through distortion units. As a result, not only are more harmonics introduced

into the bass timbre without it sounding particularly distorted but you can use

small EQ cuts to mould the sound into the mix without having to worry about

higher frequency elements, creating confl icts with instruments sitting in the

mid-range.

If the bass is still being sequenced from a tone module or sampler, then

before applying any effects you should attempt to correct the sound in the

module itself. As covered in an earlier chapter, we can perceive the loudness

of a sound from the shape of its amplitude envelope and harmonic content,

so simple actions such as opening the fi lter cut-off or reducing the attack and

release stage on both the amplitude and the fi lter envelopes can make it appear

more prominent. If both these envelopes are already set at a fast attack and

release, then layering the kick from a typical rock kit over the initial transient of

the bass followed by some EQ sculpting can help to increase the attack stage,

but at the same time, be cautious not to overpower the track’s original kick.

Although most genres of dance will employ synthetic timbres, on occasion they

do utilize a real bass guitar, and if so, a slightly different approach is required

when mixing. As previously mentioned, bass cabs will roll off most high frequen-

cies, reducing most high-range confl icts, but they can also lack any real bottom-

end presence. As a result, for dance music it’s quite usual to layer a synthesizer’s

sine wave underneath the guitar to add some more bottom-end weight.

This technique can be especially useful if there are severe fi nger or string noises

evident, since the best way to remove these is to roll off everything above

300 Hz. More importantly, though, unlike tone modules where the output is

compressed to even level, bass guitars will fl uctuate widely in dynamics and

these must be brought under control with compression. Keep in mind that

no matter what the genre of dance, the bass should remain even throughout

the mix and remain consistent. If it fl uctuates in level, the whole groove of the

record can be undermined.

If after trying all these techniques there is still a ‘marriage’ problem between

kick and bass, then it’s worth compressing the kick drum with a short attack

stage so that its transient is captured by the compressor. This will not only make

the kick appear more ‘punchy ’ but also allow the initial pluck of the bass to pull

Mixing

CHAPTER 19

389

through the mix. That said, you should avoid compressing the kick so heavily

that it begins to ring, as this will only muddy up the bottom end of the mix.

As ever, the compression settings to be used are entirely dependent on the

kick in question but generally a good starting point is a ratio of 8:1 with a fast

attack and release and the threshold set such that every kick activates the com-

pressor. Ultimately, as all bass sounds are different the only real solution is

to experiment by EQ boosting or cutting around 120 –350 Hz or by applying

heavy compression to confl icting instruments.

Vocals

Although vocals take priority over every other instrument in a pop mix, in

most genres of dance they will take a back seat to the rhythmic elements of a

mix. Having said that, they must be mixed coherently since while they may sit

behind the beat, the groove relationship and syncopation between the vocals

and the rhythm is what makes us want to dance. Subsequently, you should

exercise great care in getting the vocals to sit properly in the mix.

Firstly, it should go without saying that the vocals should be compressed so

that they maintain a constant level throughout the mix without disappear-

ing behind instruments. Generally speaking, a good starting point is to set the

threshold so that most of the vocal range is compressed with a ratio of 9:1 and

an attack to allow the initial transient to pull through unmolested.

The choice of compressor used for this is absolutely vital and you must choose

one that adds some ‘character’ to the vocals. Most of the compressors that are

preferred for vocal mix compression are hardware units such as the LA 2A and

the UREI 1176, but the Waves RComp plug-in followed by the PSP Vintage

Warmer can produce good results. This is all down to personal choice, though,

and it’s prudent to try a series of compressors to see which produces the best

results for your vocals.

It’s worth noting that even when compressed it isn’t unusual to automate the

volume faders to help the vocals stay prominent throughout. It’s quite com-

mon to increase the volume on the tail end of words to prevent them from dis-

appearing into the background mix. If you take this approach, you may need

to duck any heavy breath noises but you should avoid removing them between

phrases, otherwise they could sound false.

Once compressed, vocals will or should rarely require any EQ as they should

have been captured correctly at the recording stage and any boosts now can

make them appear unnatural. That said, small decibel boosts with a 1/2 octave

Q at 10 kHz can help to make the vocals appear much more defi ned as the

consonants become more comprehensible. If you take this ‘clarity’ approach,

however, it’s prudent to use it in conjunction with a good de-esser. This will

remove the sibilance boosting at 10 kHz but will leave the body of the vocals

untouched. This must be applied cautiously, otherwise it could introduce lisps.

PART 3

Mixing & Promotion

390

Alternatively, if the vocals appear particularly muddy in the mix, an octave Q

placing a 2 dB cut at a centre frequency of approximately 400 Hz should remove

any problems. If, however, they seem to lack any real energy while sitting in the

mix, a popular technique used by many dance artists is to speed (and pitch)

the vocals up by a couple of cents. While the resulting sound may appear ‘off the

mark’ to pitch-perfect musicians, it produces higher energy levels that are per-

fectly suited towards dance vocals; besides, not many clubbers are pitch-perfect.

It’s also sensible to add any of the effects you have planned for the vocals. As

these play an important part in the music, they must fi t now rather than later

as any instruments that are introduced after them should have their frequencies

reduced if they confl ict with the vocals or effects. For instance, it’s quite typi-

cal to apply a light smear of reverb to the vocals (remember the golden rule,

though!) to help them produce a more natural tone, but if this were applied

later in the mix you may fi nd yourself EQ’ing the effect to make room for other

instruments, which can produce unnatural results.

Synthesizers/Pianos/Guitars

The rest of the instruments in a mix will (or should) all have fundamentals

in the mid-range. Generally speaking, you should mix and EQ the next most

important aspect of the mix and follow this with progressively less impor-

tant sounds. If vocals have been employed, there will undoubtedly be some

frequency masking where the vocals and mid-range instruments meet, so you

should look towards leaving the vocals alone and applying EQ cuts to adjust

the instrument. Alternatively, the mid-range can benefi t from being inserted

into a compressor or noise gate, with the vocals entering the side chain so that

the mid-range dips whenever the vocals are present. This must be applied cau-

tiously and a ‘duck’ of 1 dB is usually suffi cient; any more and the vocals may

become detached from the music.

Most mid-range instruments will contain frequencies lower than necessary, and

while you may not actually be able to physically hear them in the mix, they

will still have an effect of the lower mid-range and bass frequencies. Thus, it’s

prudent to employ a shelving fi lter to remove any frequencies that are not con-

tributing to the sound within the mix. The best way to accomplish this is to set

up a high-shelf fi lter with maximum cut and, starting from the lower frequen-

cies, sweep up the range until the effect is noticeable on the instrument. From

this point sweep back down the range until the ‘missing’ frequencies return and

stop. This same process can also be applied to the higher frequencies if some

are present and do not contribute to the sound when it’s sitting in the mix.

Generally, keyboard leads and guitars will need to be towards the front of the

mix but the exact frequencies to adjust will be entirely dependent on the instru-

ment and mix in question. Nevertheless, for most mid-range instruments, it’s

worth setting the Q at an octave and applying a cut of 2 –3 dB while sweeping

across 400 –800 Hz and 1 –5 kHz. This often removes the muddy frequencies

and can increase the presence of most mid-range instruments.

Mixing

CHAPTER 19

391

Above all, try to keep the instruments in perspective by asking yourself ques-

tions such as:

■ Is the instrument brighter than the hi-hats?

■ Is the instrument brighter than a vocal?

■ Is the instrument brighter than a piano?

■ Is the instrument brighter than a guitar?

■ Is the instrument brighter than a bass?

What follows is a general guide to the frequencies of most sounds that sit in the

mid-range along with the frequencies that contribute to the sound. Of course,

whether to boost or cut will depend entirely on the effect you wish to achieve.

PIANOS

■ 50 –100 Hz: Add weight to the sound

■ 100 –250 Hz: Add roundness

■ 250 –1000 Hz: Muddy frequencies

■ 1 –6000 Hz: Add presence

■ 6 –8000 Hz: Add clarity

■ 8 –12 000 Hz: Reduce hiss

ELECTRIC GUITARS

■ 100 –250 Hz: Add body

■ 250 –800 Hz: Muddy frequencies but may add roundness

■ 1 –6000 Hz: Allow it to cut through the mix

■ 6 –8000 Hz: Add clarity

■ 8 –12 000 Hz: Reduce hiss

ACOUSTIC GUITARS

■ 100 –250 Hz: Add body

■ 6 –8000 Hz: Add clarity

■ 8 –12 000 Hz: Add brightness

SYNTH LEADS/STRINGS/PADS

■ 50 –100 Hz: Add bottom-end weight

■ 100 –250 Hz: Add body

■ 250 –800 Hz: Muddy frequencies

■ 1 –6000 Hz: Enhance digital crunch

■ 6 –8000 Hz: Add clarity

■ 8 –12 000 Hz: Add brightness

WIND INSTRUMENTS

■ 100 –250 Hz: Add body

■ 250 –800 Hz: Muddy frequencies

■ 800 –1000 Hz: Add roundness

■ 6 –8000 Hz: Add clarity

■ 8 –12 000 Hz: Add brightness

PART 3

Mixing & Promotion

392

PROCESSING AND EFFECTS

We’ve looked at the various effects in previous chapters, so rather than reiterat-

ing it all we’ll just say that you should refrain from using any effects during the

mixing process (bar the vocals) and only once the mix is together should you

consider adding any effects. Even then, you should only apply them if they are

truly necessary.

Always keep in mind that empty spaces in a mix do not have to be fi lled with

reverb or echo decays: a good mix works on contrast. When it comes to effects

and mixing, less is invariably more. Any effects, but particularly reverb, can

quickly clutter up a mix, resulting in a loss of clarity. Since there will probably

be plenty going on already, adding effects will only make the mix busier than

it already is and it’s important to keep some space in between the individual

instruments. Indeed, one of the biggest mistakes made is to employ effects on

every instrument when, in reality, only one or two may be needed throughout.

Therefore, before applying any effects it’s prudent to ask yourself why you are

applying them – to enhance the mix? or make a poorly programmed timbre

sound better? If it’s the latter, then you should look towards using an alterna-

tive timbre rather than trying to disguise it with effects.

Above all, remember the golden rules when using any effects:

1. Most effects should not be audible within a mix. Only when they’re

removed you should notice the difference.

2. If an effect is used delicately, it can be employed throughout the track,

but if it’s extreme, it will have a bigger impact if it’s only used in short

bursts. You can have too much of a good thing but it’s better to leave the

audience gasping for more than gasping for a break.

COMMON MIXING PROBLEMS

Frequency Masking

As touched upon earlier, frequency masking is one of the most common prob-

lems experienced when mixing, whereby the frequencies of two instruments

are matched and compete for space in the soundstage. In this instance, you

need to identify the most important instrument of the two and give this the

priority while panning or aggressively EQ’ing the secondary sound to make it

fi t into the mix.

If this doesn’t produce the results, then you should ask yourself if the confl ict-

ing instrument contributes enough to remain in the mix. Simply reducing the

gain of the offending channel will not necessarily bring the problem under

control as it will still contribute frequencies which can still muddy the mix; it’s

much more prudent to simply mute the channel altogether and listen to the

difference that makes. Alternatively, if you wish to keep the two instruments

in the mix, consider leaving one of them out and bringing it in later during

another ‘verse ’, or ‘chorus’ or after the reprise.

Mixing

CHAPTER 19

393

Clarity and Energy

All good mixes work on the principle of contrast, that is, the ability to hear

each instrument clearly. It’s all too easy to get carried away by employing too

many instruments at once in an effort to disguise weak timbres, but this will

very rarely produce a great mix. A cluttered, dense mix lacks energy and cohe-

sion, so you should aim to mix so that you can hear some silence behind the

notes of each instrument; if you can’t, start to remove the non-essential instru-

ments until some of the energy returns.

If no instrument can be removed, then aim to remove the unneeded frequen-

cies rather than the objectionable ones by notching out frequencies of the

offending tracks either above or below where the instruments contribute most

of their body. This may result in the instrument sounding ‘odd’ in solo, but if

the instrument must play in an exposed part then the EQ can be automated or

two different versions could be used.

Additionally, when working with the groove of the record, remember that the

silence between the groove elements produces an effect that makes it appear

not only louder (silence to full volume) but also more energetic, so in many

instances it’s worthwhile refraining from adding too many percussive elements.

More importantly, though, good dance mixes do not bring attention to every

part of the mix. Keep a good contrast by only making the important sounds big

and upfront, and leave the rest in the background.

Prioritize the Mix

During the mixing stage, always prioritize the main elements of the mix and

approach these fi rst. It’s all too easy to spend a full day ‘twitching’ the EQ on

a hi-hat or cymbal without getting a good balance on the most important ele-

ments. Always mix the most important elements fi rst and you’ll fi nd that the

‘ secondary’ timbres tend to look after themselves.

Mixing for Vinyl and Clubs

When mixing a record down that will be pressed onto vinyl for club play, you’ll

need to exercise more care in the frequencies you adjust. To begin with, any fre-

quencies above 6 kHz should not be boosted and all frequencies above 15 kHz

should be shelved off. On top of this, it’s also prudent to run a de-esser across

each individual track.

These techniques will help to keep the high-frequency content under some

control since if the turntable cartridges are old (as they usually are in many

clubs) it will introduce sibilance into the higher frequencies. Additionally, the

frequencies on the kick and bass should be rolled off at 40 Hz, while every

other instrument in the mix should have any frequency below 150 Hz rolled

off. While this may sound unnatural for CD, it makes for a much clearer mix

when pressed to vinyl and played over a club PA system.