Snoman R. Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART 2

Dance Genres

254

mentioning ‘dynamics’ in a previous chapter, both the kick and the snare in

trance will often remain at the highest velocity rather than following the strong –

weak – medium – weak syncopation. Again this is simply because the drums

should pull very little attention away from the main melodic lead. The closed

hi-hats, however, often employ different velocities throughout the bar to add

some interest to the patterns. As a general rule of thumb, the main emphasis

is commonly on the fi rst and fourth (remember that the open hat sits on the

third!) 16th division of the bar as illustrated below:

Bar 16 th Divisions

12345678910111213141516

SMWSSMWSSMWSSMWS

Kick Kick Kick Kick

Of course, this is simply convention and convention shouldn’t always play a

part in your music, so you should feel free to experiment by placing the accents

at different divisions on the beat. By doing so the rhythm of the piece can

change quite severely, so it is worth experimenting.

RHYTHM TIMBRES

Simply playing this rhythm through a GM module you can expect the results to

sound absolutely nothing like the pounding beats you hear in the clubs, so it’s

vital to use the right instruments to produce the sounds. Predictably, all of these

are usually derived from the Roland TR909 but the Waldorf Attack, Novation

Drum Station or a drum sampler and a series of 909 samples will perform the job

just as well. Alternatively, they can be programmed in any capable synthesizer.

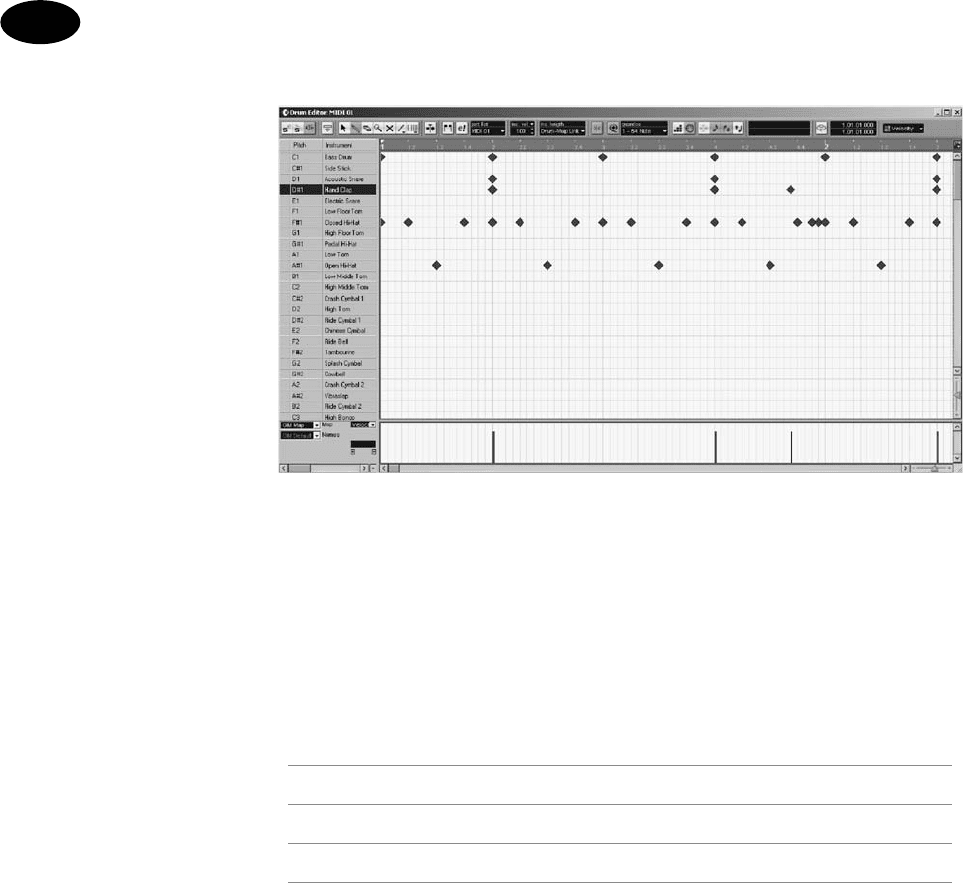

FIGURE 12.2

A variation on the

trance loop

Trance

CHAPTER 12

255

The trance kicks tend to be kept quite tight rather than ‘boomy ’ since this keeps

the entire rhythm section sounding fairly strong to produce the four-to-the-

fl oor solidity. To reproduce this try using a 90 Hz sine wave and modulate it

with a positive pitch envelope with no attack and a medium release. If you have

access to the pitch envelopes shape then generally a concave release is more

typical than convex but that’s not to say convex doesn’t produce the results.

Finally, experiment with the decay setting as the faster the decay is set, the

tighter the rhythm will become but there is a limit as to how far you should go.

If the decay is set too short then the kick will become a ‘blip’, so you should

look towards making a kick that has enough body to pull out of the mix but

not so much that it begins to boom. Generally, this, as with most instruments,

is best left as MIDI triggering the drum synth rather than bounced down to

audio as soon as it sounds appropriate, as it allows you to further contort the

kick when the rest of the instrumentation is in place.

As discussed in earlier chapters, compression can also play a large role in get-

ting the kick to sound ‘right’ and should be applied to the 4/4 kick loop, rather

than when the rest of the loop elements are in place. Although many engineers

apply compression after the loop is complete (and feel free to experiment),

keep in mind that the principle here is to ‘pump’ the drums, and if the loop

only has high-frequency elements sat off-beat – the compressor will pump

them. This can work musically with the more expensive compressors but most

budget units will destroy the high frequencies of the hats resulting in a duller

sounding loop. What’s more, as the kick and snare may occur on the same beat

a compressor with the required fast attack setting will capture the higher fre-

quencies of the snare, dulling them too.

This can be avoided by applying compression just to the 4/4 kick loop. Although

there are no underlying elements for the compressor to pump, the attack is set

as fast as possible so that the transient is compressed and some of the high-fre-

quency content is removed to produce a more substantial ‘thud’. The lower the

threshold and higher the ratio, the more this will be evident, but by increasing the

release parameter so that when the compressor is nearing the end of its release the

next kick starts, a good compressor will distort in a pleasing manner. Generally

speaking, most valve-based compressors will pump musically, but the most com-

monly used compressors for this are the Joe Meek SC 2.2, UREI LA 3 or the UREI

1176 LN due to the amount of second-order harmonic distortion they introduce.

If you don’t have access to a good valve compressor, then after compressing it with

a standard unit it’s certainly worth throwing the loop through the PSP Vintage

Warmer to recreate the requisite sound. In fact, even if it is put through a valve

compressor it’s often worth placing it through the vintage warmer anyway.

Once the kick is sounding ‘right’ the snares can be added and further modifi ed

to suit. Notably, these are not always used in the production of trance and claps

are occasionally used in their place – it depends entirely on what your creative

instincts tell you. Nevertheless, whichever is used in the track they will, more

often than not, be sourced from the TR909 or a sample CD (or more com-

monly another record). They can, of course, also be created in a synthesizer but

PART 2

Dance Genres

256

along with the triangle wave it’s worth employing a pink noise waveform rather

than white as it produces a thicker timbre. The pitch envelope is generally set

to positive modulation with a fast attack and a long decay but it’s also worth-

while creating a slurred effect by using negative modulation. This latter snare

can be used as part of a build-up to new instruments.

If a sample has been used and the decay cannot be made any longer, sending

them to a reverb unit set to a short pre-delay and tail will increase the decay.

This is also worth experimenting with even if the decay is long enough as it can

help ‘thicken’ the timbre. If this latter approach is taken, though, it’s prudent

to employ a noise gate to remove some of the reverb’s tail off. After this, much

of the low-frequency content will need removing to provide the basic snare

timbre, so it’s sensible to employ a high-pass fi lter to remove some of the low

end and then experiment with the concave and convex decay parameter (of the

amp envelope). Convex decays tend to be more popular in most trance tracks,

but concave may produce the results to suit what you have in mind.

As previously mentioned, compressors are often used on the snares to help create

the timbre, but rather than compress the transient it’s prudent to set the attack so

that it just misses and captures the decay stage instead. This will prevent the high

frequencies of the snare from being compromised, but by increasing the make-

up gain, the decay stage is increased in volume, helping to produce the often

used and distinctive thwack style timbre. Similar to the kick, the lower the thresh-

old and higher the ratio, the more this will be evident so experiment.

Finally, the closed and open hi-hat patterns will need some modifi cations to

suit the kick and snare. Yet again, these tend to be sourced from the TR909, a

sample CD or another record. However, it is sometimes prudent to programme

your own as these will play a large part in the rhythm of the record.

Ring modulation is possibly the easiest method for creating hi-hats and is eas-

ily accomplished by ring modulating a high-pitched triangle wave with a lower

pitched triangle. The result is a high-frequency noise type waveform that can

then be modifi ed with an amplifi er envelope set to a zero attack, sustain and

release with a short-to-medium decay. If there isn’t enough noise present, it can

be augmented with a white noise waveform using the same envelope. Once this

basic timbre is constructed, shortening the decay creates a closed hi-hat while

lengthening it will produce an open hat. Similarly, it’s also worth experiment-

ing by changing the decay slope to convex or concave to produce fatter or thin-

ner sounding hats.

As both these timbres depend on the high-frequency content to sit at the top

of the mix, compression should be avoided but adjusting the amplifi er decay of

synthesized hi-hats can help to change the perceived speed of the track. If the

hi-hats are sampled then this can be accomplished by importing them into a

‘drum sampler ’ such as Native Instruments Battery, or alternatively you can use a

transient designer such as SPL’s Transient Designer or the software alternative avail-

able in the Waves Transform Package. Using these to keep the decay quite short

Trance

CHAPTER 12

257

they will decay rapidly which will make the rhythm appear faster. Conversely,

by increasing the decay, you can make the rhythm appear slower. Most trance

music tends to keep the closed hi-hats quite short, though, using a short decay

but the open hats often benefi t from lengthening the decay. This can often help

the higher frequencies of the loop gel together more appropriately for the genre.

With the loop complete, it’s worthwhile looping it over a number of bars and

experimenting with the synthesis parameters or a transient designer to each instru-

ment in the loop to create a loop that gels together. This includes lengthening or

shortening the decay parameters, pitching the instruments up or down and apply-

ing effects such as reverb ( subtly!). Although at this stage it’s inadvisable to use com-

pression to warm up the loop, noise gates can be particularly useful for creating

loops with a different rhythmic fl ow. By feeding the entire loop into the gate and

reducing the threshold so that the transients of all the instruments pull though,

shortening the release parameter on the gate will cut some instruments short.

BASS RHYTHM

With the drum groove laid down, most artists then move onto the bass rhythm.

This, in many trance records, commonly consists of simple 8th notes with very

little movement in pitch or in the timbre itself. The reason for this is to leave

more ‘room’ for other elements such as the inter-melodic lines and the chorded

reprise after the middle eight of the track. For this technique to work the bass

most usually sits off the beat rather than on it since they’re kept relatively short

and play a very simple pattern to help keep the focus on the melodic lead.

If they occurred on the beat the groove would sound similar to a march because

there would be no low-frequency energy (LFE) in between the kicks. As a result,

the rhythm would have a series of ‘holes’ in between each kick/bass hit.

Kick … . Kick … . Kick … . Kick … .

Bass … . Bass … . Bass … . Bass … .

To avoid this, the bass commonly sits an eighth after the kick resulting in:

Kick Kick Kick Kick

… Bass … Bass … Bass … Bass

What’s more, by adopting this technique there is a more substantial groove

to the music since the two LFE signals are in effect working as a very basic

Da Capo (binary phrase) throughout the track. That is, the fi rst low-frequency

signal (the kick) is asking a question which is answered by the second low fre-

quency (the bass).

Of course, this, like everything, is open to artistic interpretation, and while it

is generally recommended that the bass occurs after the kick, it isn’t necessary

PART 2

Dance Genres

258

to place it an eighth after. Indeed, by experimenting through moving it subtly

around the off-beat, the groove can become more intense or relaxed. Also, it

isn’t compulsory to use notes that are an eighth in length. While these are com-

monly used to allow the timbre’s characteristics to be evident, smaller notes

can be used to great effect. Similarly, if the track is quite simple even with the

main melody, increasing the length of the notes to a quarter allows more of the

basses character to be evident which can be especially useful if the bass features

lengthy timbre augmentation with LFOs or envelopes.

Generally the bass, as with all the melodic elements of trance, works on a looped

eight-bar basis – that is the melodies, chords and so forth all loop around every

eight bars (usually with a cymbal crash or short snare roll at the end of the eighth

bar to denote the end of the musical passage). This helps to keep the repetition

that forms the basis of the music. Thus, the bass can be programmed over two

bars as a simple series of one pitch notes that can then be pasted to create the

other six bars. Working this way, you can select and pitch each consecutive two

bars of notes up and down to create some movement in the rhythm.

The technique of pitching an entire bar rather than any individual notes within

bars is very common since pitch-shifting constituent notes creates a much more

noticeable bass rhythm. This not only dissuades the focus from the main mel-

ody but also lays down a series of musical ground rules as to how the melody

can be written.

Keep in mind that if the bass features plenty of movement in a bar, for the

track to remain musical, the melody should harmonize with this progression.

However, by keeping the bass at one pitch throughout a bar and only moving

an entire bar up or down the only ground rules to the melody are to harmo-

nize with the movements of the entire bar allowing for more experimentation

on the lead. Of course, this again is merely the conventional approach used

by most trance artists and the example track, and it’s certainly open to artistic

licence. For example, some tracks will keep the bass off-beat but not maintain

even spaces between each hit, thus creating a rhythmic drive to the bass. Tracks

of this nature, however, will usually employ less melodic leads ( Figure 12.3 ).

BASS TIMBRE

For the bass timbre, analogue synthesizers (or DSP equivalents) are invariably

chosen over digital since the bass is exposed from the kick and the ‘distortion’

introduced by analogue produces a warmer tone to complement the kick.

Trance basses are sometimes sourced from sample CDs but many artists have

commented that they prefer to create their own in a synth. Generally speaking,

any analogue synth will produce a good analogue bass but many trance musi-

cians often rely on the Novation Bass Station (VSTi), the Novation SuperNova ,

Novation V-Station (VSTi) or the Access Virus to produce the timbres. Using any

of these, possibly the easiest solution for this timbre is to dial up a preset bass

in a synth and then contort the results to suit the tune. If, however, you wish

Trance

CHAPTER 12

259

to program your own a good starting point is to employ a pulse and sine (or

triangle) oscillator and detune them ⫹ or ⫺ 5 to produce the basic tone. In

general, a heavy transient pluck is not entirely necessary since it isn’t compet-

ing with the kick. Thus, the amp and fi lters attack and decay parameters can be

quite long and, in many instances, the decays actually act as the release param-

eters due to the relatively short duration of the notes.

When using the decay as a release parameter, the amplifi er’s release can then

be used as a ‘fi ne tune ’ parameter to help the bass sit comfortably in with the

drum loop. Additionally, by shortening the attack and decay parameter of

the fi lter envelope, set to modulate at a positive depth, more of a pluck can

be introduced into the sound so that the tone also complements the drum

rhythm. In fact, it’s essential to accomplish this rhythmic and tonal interaction

between the drum loop and the bass by playing around with both the amp and

the fi lters A/D EG before moving on. This is the underpinning of the entire

track, and if it’s weak, any instrumentation dropped on top will not rescue it.

By and large, most trance music doesn’t employ any velocity changes on the bass

rhythm as this is usually associated to control the fi lter cut-off, so the harder it’s

struck, the more the fi lter opens and the more of a pluck it exhibits. This type

of timbral variation is often avoided in order that the bass doesn’t demand too

much attention and rather simply ‘pulses’ along to lay down a solid foundation

for the lead and counter melodies. It is, of course, always prudent to experiment,

and it’s also worth editing the synth so that velocity controls other parameters.

On the subject of experimentation, delay, distortion and compression are often

used on basses. While most effects should be avoided since they tend to spread

the sound across the image (which destroys the stereo perspective) small

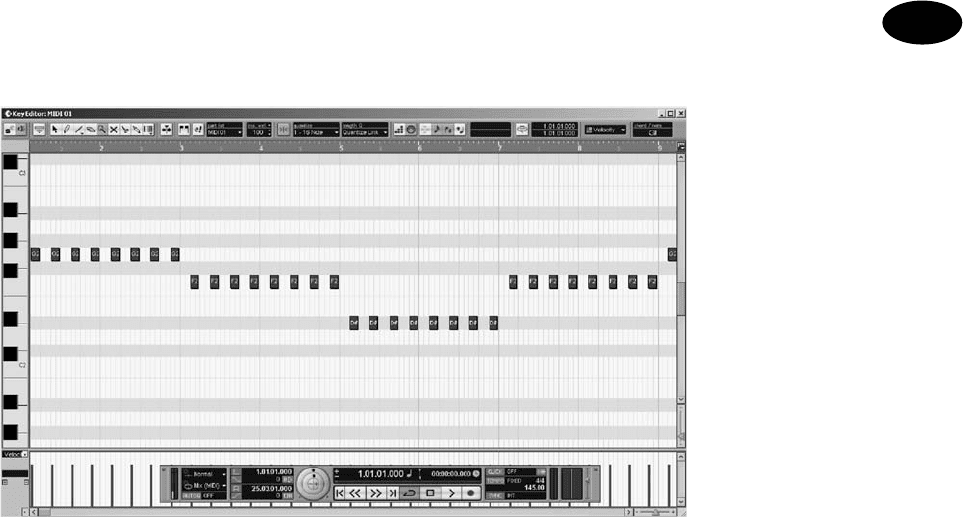

FIGURE 12.3

A typical trance bass

rhythm

PART 2

Dance Genres

260

amounts of controlled distortion can help to pull the bass out of the mix or

give it a much stronger presence. Similarly, a conservatively applied delay effect

can be used to create more complex sounding rhythms that will not place any

musical ‘restrictions’ on the lead. Any effects should be applied cautiously,

though, as the purpose of the bass is not to draw attention to itself but simply

underpin the more important elements.

Also, while it’s true to say that the sounds from any synthesizer are already

heavily compressed at the source, the principle behind a compressor here is

to control the results from any preceding effects and to be used as an ‘effect’

itself. Using the exactly same methods as compressing the kick, lengthening or

shortening the release parameter can introduce a different character to the bass.

More importantly, though, with both the drums and bass laid down, if they’re

both fed into a compressor (with the hi-hats muted), it can be set to activate on

each kick which results in it pumping the bass. Generally, the best compressors

to use for this should be either valve or opto due to the second-order harmonic

distortion they introduce, as this helps the mix to pump more musically. Again

this means using the Joe Meek SC 2.2, UREI LA 3 or the UREI 1176 LN, but if

you don’t have access to these, the Waves C1, C4 or Renaissance compressors

will do the trick or the PSP Vintage Warmer if you need more warmth.

Naturally, the amount of compression applied will depend upon the timbres

used, but as a general guideline, start by setting the ratio to 9:1, along with an

attack of 5 ms and a medium release of 200 or so milliseconds. Set the thresh-

old control to 0 dB and then slowly decrease it until every kick registers on the

gain reduction meter by at least 3 dB. To avoid the volume anomaly (i.e. louder

invariably sounds better!), set the make-up gain so that the loop is at the same

volume as when the compressor is bypassed and then start experimenting with

the release settings. By shortening the release the kicks will begin to pump the

bass, which becomes progressively heavier the more that the release is short-

ened. Unfortunately, the only guidelines for how short this should be set are

to use your ears and judgment but try not to get too excited. The idea here is

to help the drums and bass gel together into a cohesive whole and produce a

rhythm that punches along energetically. On the same note, it should not be

compressed so heavily that you lose the excursion of the kick altogether!

Once these two elements are working together, it’s prudent to export the groove

as the four separate two-bar loops of audio and drop them into a sampler. This

allows you to trigger the groove from numerous points along the arrangement

and also permits you to experiment with different progressions by simply hitting

the appropriate key on the sampler. It’s also sensible to export the drum track

alone and keep a note of all compression or effects settings along with the origi-

nal MIDI fi les to come back to later. Most studios will create these ‘track’ sheets,

and it’s wise to do so since many remixers will expect a track sheet if they’re to

remix the music. What’s more, having the groove as a cohesive whole and sat in

a sampler can often speed up the production process since you already have a

groove you’re happy with and therefore are less likely to be tempted to make more

‘tweaks ’ when they aren’t required. In other words, the rest of the instruments

Trance

CHAPTER 12

261

have to be programmed to fi t the groove, rather than constantly tweaking all

instruments to make them all fi t together. Not only this prevents you from

spending months constantly making unnecessary tweaks, but also most tracks

will start with just the groove!

TRANCE MELODIES

With the basic groove laid down a good approach is to programme the melody

before any further elements are programmed since this will often dictate the

direction of any other instrumental counter melodies.

Creating a melodic lead line for trance is possibly the most diffi cult part, as a

good lead is derived from not only the melody but also the timbre and both

of these have to be ‘accurate, ’ so close scrutiny of the current scene and mar-

ket leaders is absolutely essential in acquiring the right feel for the dance fl oor.

Unfortunately, in terms of MIDI programming, trance leads follow very few

‘ rules, ’ so how to programme one is entirely up to your own creative instincts.

That said, as ever there are some general guidelines that can be applied.

Firstly, in many cases the lead is constructed using a ‘chorded’ structure so that

the notes alternate between two notes. This creates the results of jumping from

the ‘key’ of the song to a higher note before returning to the main key again

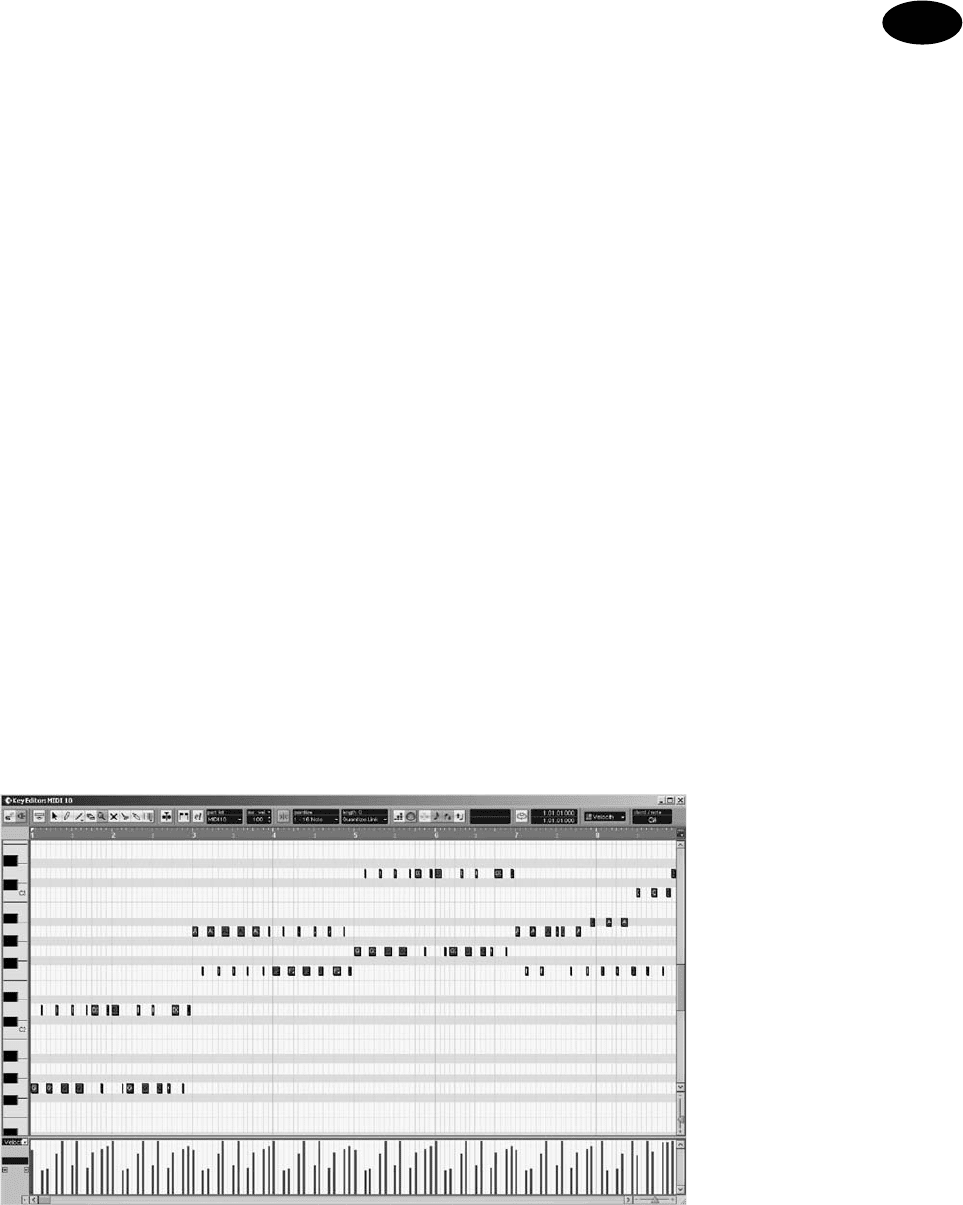

(Figure 12.4 ).

Also, as the above diagram shows, this lead continues over eight bars before

being repeated again and each consecutive two bars of music will tend to rise

in pitch rather than fall. Indeed, this building up the scale plays a key role in

creating trance leads for the dance fl oor. By progressively moving up the scale

FIGURE 12.4

A trance melody

PART 2

Dance Genres

262

throughout the bars and then setting the few fi nal notes of the last bar higher

in scale than any of the preceding notes an uplifting feel results. Conversely, by

setting the fi nal notes lower than that of the start of a bar the feeling is reversed,

resulting in a track that pulls the listener down.

To keep the relative speed and energy of trance, it’s better to keep the notes

short and stabby. This means using a mix of 32nd, 16th and/or 8th notes and

then using the decay and release envelope of the amplifi er to lengthen and

contort the timbre if required. This gives much more control over the groove,

allowing you to immediately adjust the ‘feel’ of the music by simply adjusting

the amplifi er’s release envelope rather than having to ‘kick’ MIDI notes around.

With these guidelines in mind, a lead can be constructed in any manner, but if

inspiration has left you, there are some techniques that can sometimes produce

good results. The fi rst and possibly easiest method is to begin by fashioning a

chord structure from the previously programmed bass line. This can follow the

progression exactly, but generally it’s worthwhile experimenting with a mix of

parallel, oblique or contrary motions. For instance, in the example track the

bass played over eight bars and consisted of:

Bar 1 Bar 2 Bar 3 Bar 4 Bar 5 Bar 6 Bar 7 Bar 8

G G F F D# D# F F

Thus, the key of the lead could follow this progression exactly in a parallel

motion which would produce musically ‘acceptable’ results, even though it

would be somewhat a little boring to the ear. However, by following the pro-

gression in a parallel motion for only the fi rst, second and fourth bar and using

a contrary motion on the third, the interaction between the lead and the bass

exhibits a much better result:

Bar No 12345 6 78

Bass G G F F D# D# F F

Lead G and

D

G and

D

F and

A

F and

A

G and

D

G and

D

F and

A

F and

A

Of course, it isn’t imperative that the third bar becomes contrary and any or

all bars could be contrary, or parallel, or oblique, provided that it sounds right

to you.

Once this basic chord is constructed to complement the bass, using a noise gate

or MIDI CC messages you can cut up each bar in a rhythmic manner. If using

CC messages, though, a much better approach is to write a complex rhythmic

hi-hat pattern and then use the sequencer to convert the hi-hats notes to CC11

messages rather than programme all the CC’s in by hand. This can often lead

Trance

CHAPTER 12

263

to a robotic nature, whereas using a hi-hat pattern you’re much more likely to

produce a rhythmic fl owing gate. Alternatively, you can use a side chain from

the hi-hats or kick drum to pump the chords. This gated effect, once suitable,

can be applied physically to the notes (i.e. cut them up to produce the effect)

so that not only does each note retrigger the synth but also it permits you to

offset the top notes of a chord against the lower ones to produce the alternat-

ing notes pattern that’s often used for the leads.

Alternatively, another frequently used method to create a trance melody is to

begin with a synthesizer’s arpeggiator, as this can help to get the general idea

down. With some trial and error it’s possible to fi nd both arpeggiator pattern

and chord combination to produce some inspiration for a lead melody. Once

recorded as MIDI, this can be further attuned in a sequencer’s key editor.

Another technique that’s often referred to as the ‘two fi ngered ’ approach can

produce useable results too. This involves tapping out a riff using just two keys

an octave apart on the keyboard. By alternating between these two keys keep-

ing the lower key the same and continually moving higher in scale on the sec-

ond key while playing the audio through a delay unit can produce interesting

rhythmic movements. If this is recorded as MIDI information, it can be edited

further by lengthening notes so that they overlap each other slightly or by add-

ing further notes in between the two octaves to construct a melody that builds.

MELODIC TIMBRES

Just as the melody for the lead is important, so is the timbre, and it’s absolutely

vital that time is taken to programme a good one – the entire track will stand

or fall on its quality. As discussed in the chapter on sound design, the lead is

the most prominent part of a track and hence the main instrument that sits in

the mid-range/upper mid-range. Consequently, it should be rich in harmonics

that occupy this area and should also exhibit some fl uctuations in the charac-

ter to remain interesting. This can sometimes be accomplished through mod-

ulating the pitch with an LFO on a digital synth, but the phase initialization

from analogue synths, more often than not, will produce much better, richer

results. Consequently, the preferred synths by many artists are the Access Virus ,

the Novation SuperNova, Novation A-Station or the Novation V-Station (VSTi).

We’ve already covered the basic principles behind creating a harmonically rich

lead, so rather than go into too much detail again here, what follows is a quick

overview:

■ Oscillators:

■ 2 ⫻ pulse detuned by ⫺ 5 and ⫹ 4 cents

■ 1 ⫻ sawtooth (try pitching this up or down an octave)

■ 1 ⫻ pink noise

■ Amp and fi lter envelope:

■ Zero attack

■ Medium decay