Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

movies. He found out specifically why she wanted him

when he was called into her dressing room. In Leonard

Maltin’s interview book, Behind the Camera, Howe relates

the story as follows: “‘You know why I like these pictures,

Jimmy? Because you made my eyes go dark.’ She had pale

blue eyes, and in those days the film was insensitive to blue,

and they washed out. And I didn’t realize how I’d made her

eyes go dark! I walked and stood where I took the pictures,

and there was a huge piece of black velvet. Something told

me, ‘Well, it must be a reflection. The eye is like a mirror.

If something is dark, it will reflect darker.’ So I cut a hole in

it (the velvet), and put my lens through, and made all her

close-ups that way . . . that’s how I became a cameraman. . . .

Everybody who had light blue eyes wanted to have me as

their cameraman!”

It was a time of innovation. Movies were young and the

camera was often a mystery, even to those who depended

upon it for their living. But Howe was a master of unlocking

the camera’s secrets, and his contributions to the 118 feature

films he worked on are incalculable.

His first was Drums of Fate (1923) starring, of course,

Mary Miles Minter. He photographed all genres of film,

from swashbucklers such as The Prisoner of Zenda (1937) to

war movies such as Air Force (1943). He was just as sensitive

to boxing movies, such as the stunningly photographed Body

and Soul (1947), as he was to musicals, such as his crisp Ya n -

kee Doodle Dandy (1942). One of his most memorable movies,

a film that benefited from his knowledge and expertise with

shooting in black and white, was

JOHN FRANKENHEIMER

’s

Seconds (1967).

HOWE, JAMES WONG

208

James Wong Howe, one of Hollywood’s greatest cinematographers, was given the nickname Low Key Howe. His low-key

lighting style gave a distinctively dark and moody look to the films noir of the 1940s.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE

STAR NEWS)

Howe dabbled with directing, making one movie, Go

Man Go, in 1952. Happily, he returned to cinematography,

working until 1975 and ending his illustrious career that year

with Funny Lady.

Hudson, Rock (1925–1985) A performer whose

career in the late 1940s and early 1950s was based strictly on

his good looks but who slowly emerged as a competent and

popular actor. Hudson began in action pictures and west-

erns, moved on to romantic dramas in the mid-1950s, and

then flowered in light romantic comedies in the late 1950s

and early 1960s. His career was heavily based on his strong

masculine image but, ironically, it was well known within the

Hollywood community that he was a homosexual. His secret

finally emerged in the media when he fell ill and then died

of AIDS.

Born Roy Scherer Jr., he later took his stepfather’s last

name of Fitzgerald. After graduating from high school he

became a mailman and then a mechanic in the navy during

World War II. He drifted from job to job after the war,

unsure of his direction. Told that with his looks he ought to

be in pictures, he drifted to Hollywood and found that the

movie people agreed. His name was changed to Rock Hud-

son (as fake a name as the industry has ever conjured), and he

was given his chance in a small role in Fighter Squadron

(1948). With no training as an actor whatsoever, he required

38 takes before the director was satisfied with his first line. It

became easier after that, but his was a long learning process

that took several years.

Audiences liked him, though, and he continued to learn

his craft in ever larger roles in low-budget action movies and

westerns such as Undertow (1949), I Was a Shoplifter (1950),

Winchester ’73 (1950), The Desert Hawk (1950), and Toma-

hawk (1951).

By late 1951 and early 1952, Hudson had become a

leading man in a number of films, rounding out the casts of

such modest movies as Bright Victory (1951), and two

BUDD

BOETTICHER

westerns, Horizons West (1952) and Seminole

(1953). His big break came in 1954 when he played the male

lead in Magnificent Obsession, a romantic movie that scored

heavily at the box office, propelling him to matinee-idol sta-

tus. Although he continued acting in occasional action

films, his career veered toward movies such as One Desire

(1955), aimed primarily at female fans, and several Douglas

Sirk films, including All That Heaven Allows (1956), Written

on the Wind (1957), and Tarnished Angels (1958), films that

were dismissed as mere “women’s pictures” in the 1950s but

that have since become considered minor classics.

Nonetheless, Hudson’s most important role of the mid-

1950s was in the epic Giant (1956), in which he starred with

ELIZABETH TAYLOR

and

JAMES DEAN

and for which Hud-

son was honored by his peers with an Oscar nomination as

Best Actor.

After a decade in Hollywood, Hudson entered the most

memorable phase of his career when he costarred with

DORIS

DAY

in Pillow Talk (1959), a bright, breezy comedy that, for its

day, was considered mildly risqué. The film was a huge hit,

and Hudson and Day were teamed together in Lover Come

Back (1961) and Send Me No Flowers (1964). They made just

those three films together, but the impact they had was so

great that it is often assumed that they acted together far

more frequently. Hudson did go on to make other light

comedies, including Man’s Favorite Sport (1964) and Strange

Bedfellows (1965), but they did not feature Day.

Hudson surprised audiences and critics alike when he

starred in

JOHN FRANKENHEIMER

’s brilliant Seconds (1966). It

was unarguably the actor’s best performance in his nearly 20

years in the movie business. The film, unfortunately, was

ahead of its time, so it wasn’t the hit it should have been. No

other major box-office winners followed and, despite his still

youthful good looks, his film career was suddenly in jeopardy.

He continued to make the occasional movie during the

1970s but with little effect. Instead, he wisely put his efforts

into developing a television career. He starred in the hit show

McMillan and Wife from 1971 through 1975. In the last

decade of his life, he tried starring in two other TV series,

neither of which caught on, and later made a modest come-

back in a recurring role in the prime-time TV soap Dynasty.

In the end, however, he will probably be remembered by

many as the first major Hollywood star to die of AIDS.

Hughes, Howard (1905–1976) This eccentric bil-

lionaire remains one of the most fascinating figures in Hol-

lywood history despite the relatively few movies with which

he is closely associated. But in spite of his modest output as

a producer, Hughes is directly responsible for having cre-

ated three movie stars and four landmark films. He is also

the man who presided over the demise of

RKO RADIO PIC

-

TURES

,

INC

.

Hughes began life with a silver spoon in his mouth—he

was the son of the man who revolutionized the oil industry

with the invention of a new, powerful drill bit—but he pro-

ceeded to turn that spoon to platinum. Tragically, both

Hughes’s parents died within two years of each other while

he was in his teens. The orphan millionaire took over the

Hughes Tool Company at the age of 18 and decided soon

thereafter to go into the movie business.

Hughes’s Uncle Rupert was one of Hollywood’s most

successful screenwriters, and it was through this relation that

Hughes had become acquainted with the movie business. His

Uncle Rupert, however, advised him to stay out of Holly-

wood and was of no help to him, except inadvertently to spur

the stubborn 20 year old on to success.

Hughes’s career as a producer started badly. He made

Swell Hogan (1925) starring Ralph Graves, a movie so poor

that Hughes refused to ever let it be shown. The second

film he produced was Everybody’s Acting (1926), which was a

modest hit. His third film, however, brought him a measure

of respect in a town that had written him off as a naive rich

kid. The movie was Two Arabian Knights (1927), and it won

the

ACADEMY AWARD

as Best Director of a Comedy for

LEWIS MILESTONE

.

With his early success, Hughes was emboldened to make a

film that was close to his heart. The young man was fascinated

HUGHES, HOWARD

209

by airplanes, and his next movie, Hell’s Angels (1930), was

devoted to them. The film project was begun in 1928, but this

time Hughes was intimately involved in the production. It was

with Hell’s Angels that he was deservedly tagged with the repu-

tation of being both a meddler and a perfectionist. Two other

Hughes productions would be released while this movie, a

labor of love, was being filmed. After two directors quit

because of his interference, Hughes finally took over the direc-

torial chores of Hell’s Angels himself.

The movie was shot as a silent film, but most of the

footage had to be tossed out (except for the aviation scenes)

because of the talkie revolution. For the reshooting, one

important addition was made by Hughes; he hired a virtually

unknown actress,

JEAN HARLOW

, as his new leading lady. In

the process, he turned her into a star.

The film was a hit, thanks to Harlow and the aviation

footage. The total cost of the film (excluding the human toll

of three fliers who died in crashes during the production) was

nearly $4 million. Despite its box-office pull, the movie was

so expensive that it barely broke even.

Hughes went on to produce other films in the early

1930s, and two of them were truly memorable. The first of

these was The Front Page (1931), directed by Lewis Milestone

and based on the hit play by

BEN HECHT

and Charles

MacArthur. This comedy about journalists established the

image of newspapermen as tough, wisecracking, and

resourceful loners.

The second important film Hughes produced in the early

1930s was Scarface (1932), the gangster movie that launched

PAUL MUNI

’s film career as well as hastened the strict

enforcement of the

HAYS CODE

.

After Scarface, Hughes temporarily ended his career as a

producer. He later resurfaced, making The Outlaw (1943), the

first “sexy” western. In the process, he turned busty 19-year-

old

JANE RUSSELL

into a star, just as he had Jean Harlow a

decade earlier. The racy film was an enormous success

despite its poor quality, but more important, it was a break-

through in the effort against movie censorship.

Through the balance of World War II, Hughes, a pioneer

in commercial aviation, concentrated on aviation projects for

the war effort.

He returned to Hollywood in the latter half of the 1940s,

producing, among other things, Mad Wednesday (1947), with

PRESTON STURGES

directing. The film, starring the former

silent-screen comedian

HAROLD LLOYD

, had its moments,

but it was poorly received by audiences.

Hughes then stunned Hollywood by purchasing the ail-

ing RKO studio in 1948, which he proceeded to run into the

ground over an eight-year period before selling it in 1955.

He made very few quality movies during his RKO period,

although there were some modest money-makers. The best

of the lot were Flying Leathernecks (1951) and Split Second

(1953). At the end of his Hollywood career, he tried to top

the success of Hell’s Angels with Jet Pilot (1957), but the film

was both an artistic and commercial failure.

The enigmatic Hughes meant more to Hollywood than

the movies he produced. He was a symbol of its excesses and

eccentricities—and also of its glamour. He dated some of the

movie capital’s most famous stars, including

KATHARINE

HEPBURN

,

OLIVIA DE HAVILLAND

,

GINGER ROGERS

,

LINDA

DARNELL

,

LANA TURNER

,

BETTE DAVIS

,

YVONNE DE

CARLO

,

ELIZABETH TAYLOR

,

AVA GARDNER

, and Jean Peters,

whom he married in 1955.

Hughes, who had been living outside of the United

States, died while being transported to Texas by airplane. For

a man who loved airplanes as much as Hughes, to die while

in flight was certainly an ironic end.

Hughes, John (1950– ) A screenwriter, director, and

sometime producer who cornered the 1980s youth market,

making both thoughtful and entertaining movies about

teenagers from their point of view. Less well known is the

fact that Hughes has also been a successful writer-director of

outlandish comedies, responsible in large measure for many

of the National Lampoon films of the last decade.

Hughes began his show business career as a gag writer

before succumbing to the lure of advertising. When his

unusual sense of humor could no longer be contained, he

began to write for National Lampoon magazine, eventually

becoming a contributing editor. His association with the

magazine brought him the opportunity to pen the screenplay

for National Lampoon’s Class Reunion (1982). It was not well

received by the critics, but it did well enough at the box office

to successfully launch Hughes’s screenwriting career.

Though he was half responsible (he cowrote the screen-

play) for the bomb Nate and Hayes (1983), he came into his

own as a screenwriter with two major critical and box-office

hits, Mr. Mom (1983) and National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983).

His subsequent zany comedies fared less well with the critics

but were generally winners at the box office. His later hits of

this kind were National Lampoon’s European Vacation (1985),

which was based on his story, Planes, Trains, and Automobiles

(1987), which he also directed, The Great Outdoors (1988),

and Uncle Buck (1989).

His reputation as “a voice of a young generation” has

come from another set of movies. They, too, have been come-

dies but are sympathetically focused on the trials and growing

pains of teenagers and lack any trace of condescension.

Hughes directed and occasionally produced a string of these

films, making his directorial debut with Sixteen Candles (1984).

He followed that success by writing, directing, and pro-

ducing The Breakfast Club (1985), a bold and somewhat inno-

vative movie for the teen market that had the audacity to

simply let a handful of young people speak their minds on

film. It was a major hit, highlighting the talents of several

young actors and helping to turn them into teen stars, among

them Molly Ringwald, Anthony Michael Hall, Judd Nelson,

Emilio Estevez, and Ally Sheedy.

Hughes wrote several other youth-market movies,

including the pleasantly silly Weird Science (1985) and Ferris

Bueller’s Day Off (1986). He followed those films with a

departure, She’s Having a Baby (1988), a movie that chal-

lenged his teenage audience to face the prospects of marriage

and parenthood. The film was neither a critical nor a com-

mercial success.

HUGHES, JOHN

210

After directing Uncle Buck (1989), an insipid comedy fea-

turing John Candy, and Curly Sue (1991), a depression-era

throwback to

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

’s formula films that appealed

primarily to youthful audiences, Hughes found another way

to address his loyal following. He turned almost exclusively

to screenwriting about children and animals. He wrote

Beethoven (1992) and 101 Dalmatians (1996) and then wrote

the three blockbuster Home Alone films (1990, 1992, and

1997) in which the young protagonist (Macaulay Culkin, ini-

tially) brutalizes dimwitted trespassers and would-be robbers.

The last film that he wrote (as of 2004) was Maid in Manhat-

tan, a Cinderella story and vehicle for

JENNIFER LOPEZ

. Dur-

ing the 1990s Hughes also produced 13 films, including Maid

in Manhattan.

See also

BRAT PACK

;

BRODERICK

,

MATTHEW

;

TEEN

MOVIES

.

Hurt, William (1950– ) A gifted, versatile, and

unpredictable actor who has made a strong impression on the

screen in a relatively modest number of starring roles since

beginning his film career in 1980. Tall and handsome, he

could have easily been a romantic Hollywood leading man.

Instead, he has chosen to portray an odd and intriguing

assortment of characters, establishing himself as a serious

actor who cares little for the trappings of stardom.

Hurt’s father was a U.S. State Department official, and

the young boy lived in a number of exotic South Pacific

locales before his parents finally divorced. As a teenager, he

lived briefly in New York City before his mother married

Henry Luce III, the son of the founder of Time magazine.

Hurt then found himself continuing his education at the elite

Middlesex School in Massachusetts. It was there that he

started to act.

He began his college career at Tufts University as a the-

ology major but soon switched to theater. Upon graduation,

he attended Juilliard to further his study of acting.

Next, he traveled to Oregon, where he acted in a theater

festival presentation of Long Day’s Journey into Night in 1975.

Hurt later made his major breakthrough in the Circle Reper-

tory Company production of My Life in 1977, winning an

Obie (Off-Broadway) Award for his performance.

Hurt continued acting for Circle Rep through the rest of

the 1970s, refusing film offers until finally taking a leading

role in Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980). The movie

received mixed reviews, but the actor was acknowledged by

the critics. He was next cast as the hero in the thriller Eye-

witness (1981), and both he and the movie enjoyed a modest

success. His third feature, the

FILM NOIR

suspense film Body

Heat (1981), written and directed by Lawrence Kasdan, was a

solid success for both Hurt and his costar,

KATHLEEN

TURNER

(in her film debut).

Hurt, for his part, wasn’t terribly interested in stardom,

except for the clout it gave him to help get good roles. He

happily joined the large ensemble cast of

LAWRENCE KAS

-

DAN

’s highly regarded The Big Chill (1983), deliberately

played down his role as the Russian detective in the disap-

pointing Gorky Park (1983), and then took the offbeat role

of a daydreaming homosexual prisoner in the low-budget

Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985), an art-house hit that

brought Hurt an Oscar as Best Actor for his unconven-

tional portrayal.

The actor has continued to pursue good roles wherever

he can find them, often returning to the stage to work. In

films, he has continued to take on challenging roles, such as

in Children of a Lesser God (1986), knowing that deaf costar

Marlee Matlin would inevitably be the movie’s focal point,

and Broadcast News (1987) in which he played an anchorman

of mediocre intelligence, knowing that actress Holly Hunter

and actor Albert Brooks would steal the show. Happily, a

number of critics commented on Hurt’s understated per-

formance. He also reteamed with his Body Heat director

Lawrence Kasdan and costar Kathleen Turner to give yet

another quietly powerful performance in The Accidental

Tourist (1988).

During the 1990s, Hurt alternated between playing leads

and supporting roles in a wide variety of films. He starred in

Until the End of the World (1991), directed and written by

Wim Wenders, the talented German director. The following

year, he had the lead in an adaptation of Albert Camus’s The

Plague, and he played a Welsh postmaster in Second Best

(1994). One of his best roles during the decade was as the tor-

mented Rochester in still another adaptation (1996) of Char-

lotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. In One True Thing (1998) he played

a professor whose wife is dying of cancer. He had supporting

roles in several films, the most notable of which was A.I.:

Artificial Intelligence (2001).

Huston, Anjelica (1951– ) The daughter of film

director

JOHN HUSTON

was born in California but raised in

St. Clerans, County Galway, Ireland. She later moved with

her mother to London and then to New York, where she

worked as a model. She made her motion picture debut at the

age of 15 in A Walk With Love and Death, directed by her

father. In 1969, she auditioned for the role of Ophelia in

Tony Richardson’s London production of Hamlet; although

the role finally was unconventionally cast with Marianne

Faithfull, Huston played one of the ladies-in-waiting to

Queen Gertrude on both stage and screen. In the mid-1970s,

Huston moved to Los Angeles and continued her acting

career, appearing in The Last Tycoon (1976), The Postman

Always Rings Twice (1981, starring

JACK NICHOLSON

, with

whom she had a long relationship), and secondary roles in

other films. In 1985 she won an Oscar as Best Supporting

Actress in Prizzi’s Honor, directed by her father.

Her first lead was in Gardens of Stone, directed by

FRAN

-

CIS FORD COPPOLA

in 1987, the same year that she

appeared as Gretta Conroy in her father’s production of

James Joyce’s The Dead. Her presence as a remarkable con

artist in Stephen Frears’s The Grifters (1990) made the film

distinctive, as did her portrayal of the Grand High Witch in

Nicolas Roeg’s adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Witches

(1990). Another grotesque supernatural role was that of

Morticia in The Addams Family (1991) and Addams Family

Values (1993). In 1998, she played an even more sinister role

HUSTON, ANJELICA

211

as Drew Barrymore’s stepmother in Ever After: A Cinderella

Story (1998). Recent appearances include The Golden Bowl

(2000), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Blood Work (2002), and

Daddy Day Care (2003).

Huston, John (1906–1987) A director, screenwriter,

and actor who made many of Hollywood’s most admired

films during a long directorial career that spanned more than

45 years. Huston directed several kinds of films but did his

best work with serious adventure movies. He elevated such

genres as the crime drama, the detective film, the war movie,

and the boxing film to new heights of artistry. He was also an

excellent screenwriter who was a skillful adapter of other

writers’ works. In fact, the vast majority of the feature films

Huston wrote and directed were adaptations. He was among

the first wave of talented writer-directors to come into

prominence in Hollywood in the early 1940s.

During his first 12 years as a director, Huston was one of

Hollywood’s golden boys, but his reputation was later

attacked by auteurist critics who found no unifying theme in

his work. In the 1970s, however, critics rediscovered Hus-

ton’s unique and highly creative ability to direct films whose

heroes show a quixotic sort of courage, and Huston’s entire

career underwent a substantial reevaluation. Regardless of

questions of theme, however, it has always been clear that

Huston was a gifted filmmaker who made his movies with

intelligence, wit, and considerable style.

The son of actor

WALTER HUSTON

, he began and ended

his life as an actor. Huston made his stage debut at the age of

three and worked quite often with his father on the vaudeville

circuit in his youth. He nearly died when he was 12 years old

from an enlarged heart and kidney but fully recovered. Two

years later he quit high school to become a prize fighter, win-

ning 23 of 25 amateur bouts and garnering the Amateur

Lightweight Boxing Championship of California.

If his childhood wasn’t colorful enough, Huston’s early

adult life was nearly blinding in its eccentricity. He became a

professional stage actor in his late teens, enjoying some suc-

cess, but ended that to join the Mexican army, becoming a

cavalry officer. He later performed in horse shows, wrote a

musical play for puppets, and then made his film debut as an

actor in a small role in William Wyler’s The Shakedown

(1928). He went on to appear in two other early sound fea-

tures but walked away from that opportunity as well, becom-

ing a short-story writer and a reporter. The obviously

talented but unfocused Huston continued his career changes

throughout the early to mid-1930s, collaborating on several

HUSTON, JOHN

212

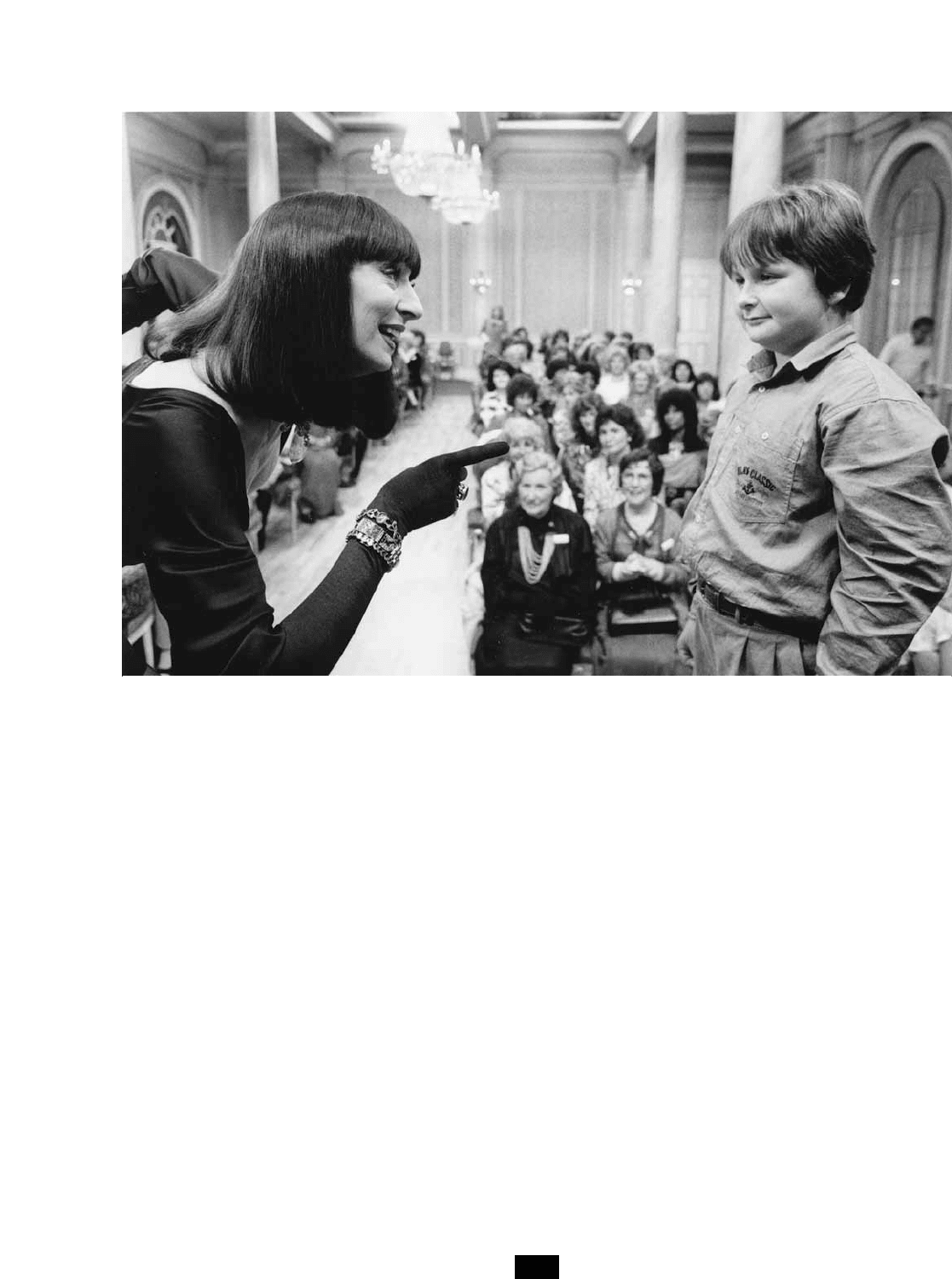

Anjelica Huston in The Witches (1990) (PHOTO COURTESY WARNER BROS.)

screenplays, most notably two that starred his father, A House

Divided (1931) and Law and Order (1932). Later, he ran off to

Europe to study art, nearly starving on the streets of Paris.

Finally, after short stints in America as a magazine editor

and, again, as a stage actor, Huston returned to Hollywood to

begin his film career in earnest. He tried his hand at screen-

writing again. This time he had a real impact, collaborating

on the screenplays of a number of major hits, among them

Jezebel (1938), The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse (1938), Dr.

Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940), and Sergeant York (1941). His

most important early screenplay, though, was for High Sierra

(1941). He had struck a deal with mogul

JACK WARNER

that

he would be allowed to both write and direct a movie of his

own if the film was a success. High Sierra was, of course, a

smash hit, and Huston had his chance.

For his first film as a writer-director, Huston decided to

remake Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, a novel that

had been turned into a film twice before. With perfect cast-

ing, tight direction, and adroit screenwriting (he was the first

to realize that Hammett’s dialogue was perfectly suitable for

the screen), Huston turned

THE MALTESE FALCON

(1941) into

one of Hollywood’s all-time classics.

He directed two more films of only modest distinction

before heading off to war as a filmmaker in the Signal Corps.

During World War II he made a number of stirring docu-

mentaries, two of which are considered landmark films, The

Battle of San Pietro (1945) and Let There Be Light (1946), the

latter so shattering in its depiction of the effects of shell

shock that it was kept under wraps by the Pentagon for sev-

eral decades.

On returning to Hollywood, Huston made what many

consider his greatest film, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

(1948). One of the first films of the studio era to be made

largely on location (in Mexico), the movie brought Huston’s

father an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor and earned the

director his only Academy Award.

The decade following The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was

a rich and rewarding one for Huston. During that time he

made many of his best movies, among them Key Largo (1948),

The Asphalt Jungle (1950, for which he was nominated for an

Oscar for Best Director), The Red Badge of Courage (1951),

The African Queen (1951, for which he was again nominated),

Moulin Rouge (1953, for which he gained yet another nomi-

nation), Beat the Devil (1954, a latter-day cult favorite), Moby

Dick (1956, an ambitious undertaking that was much better

than critics of the day realized), and Heaven Knows, Mr. Alli-

son (1957, an underrated minor masterpiece that had much in

common with his earlier African Queen).

1956 was a turning point in Huston’s career; Moby Dick

was harpooned by the critics and sank at the box office. As he

was used to one hit after another, Huston’s erratic commer-

cial success in the late 1950s and 1960s seemed like a fall

from grace. His first genuinely bad movie was The Barbarian

and the Geisha. Some fascinating critical and/or commercial

flops followed, including The Roots of Heaven (1958), Freud

(1962), The Bible (1964), Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967),

Sinful Davey (1969), and A Walk with Love and Death (1969),

the latter film starring his daughter, Anjelica Huston.

But very good movies were to be found as well, a few of

them hits, during that period: The Unforgiven (1960), The

Misfits (1961), The Night of the Iguana (1964), and Casino

Royale (1967)—all had much to recommend them.

In spite of these successful movies, it seemed as if the great

director was in serious decline. But Huston fooled those who

thought his best days were behind him when he directed one

of the finest films about boxing ever made, Fat City (1972).

Suddenly rediscovered, Huston went on to make, among

other movies, the much-admired The Man Who Would Be King

(1975), the art-house hit Wise Blood (1979), and Prizzi’s Honor

(1985), for which he won his fifth Oscar nomination for Best

Director and for which his daughter, Anjelica, won an Oscar

for Best Supporting Actress. With Anjelica’s award, the Hus-

ton family became the first Hollywood dynasty to have three

generations honored by the academy.

The final film Huston directed was James Joyce’s The

Dead (1987), a lovely effort that served as a fitting end to an

illustrious career.

But John Huston was not content to stop working. He

acted far more often in his later years. His long, evocative

face and sonorous voice made him a much-in-demand char-

acter actor, and in addition to making appearances in some of

his own films, he also acted in others’ films, including The

Cardinal (1963), Candy (1968), Chinatown (1974), The Wind

and the Lion

(1975), and W

inter Kills (1979). His last per-

formance was in his adopted son director Danny Huston’

s

Mr. North (1988), but he collapsed during the production and

asked

ROBERT MITCHUM

to replace him. John Huston died

of emphysema before the picture was completed.

Huston, Walter (1884–1950) An actor who could

always be counted on to give an intelligent, thoughtful per-

formance. Though he came to the movies in middle age and

was a rather ordinary looking man, there were few film actors

who could hold an audience’s attention like Huston; he had a

magnetic screen presence. Huston knew how to underplay a

role, and he was enormously versatile, playing everything

from historical figures to romantic leads, to villains and kindly

old characters in a film career that lasted more than 20 years.

Born Walter Houghston in Toronto, he tried to lead a

“normal” life but was ultimately drawn to acting. Trained as

an engineer, he chose to work on the stage, and did so with

modest success until marrying his first wife in 1905 (with

whom he had a son, the future writer-director John Huston).

With a wife and child to care for, Huston soon deserted the

stage for a series of jobs as an engineer.

The regular working life did not appeal to Huston, and

he eventually returned to acting in 1909, becoming a bigger

star than ever before. He was a hit in vaudeville during the

1910s and his career soared even as the first of his three mar-

riages soured. His reputation was such that Huston was

offered starring roles on Broadway in the mid- to late 1920s,

and he scored major successes on the Great White Way in

such plays as Mr. Pitt and Desire under the Elms.

Lured to Hollywood during the sound-film revolution,

he made his movie debut in Gentlemen of the Press (1928),

HUSTON, WALTER

213

soon making an impact in the title role of

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

’s

final masterwork, Abraham Lincoln (1930). The early 1930s

was Huston’s best era. He gave vivid performances in such

memorable movies as The Criminal Code (1931), A House

Divided (1932), American Madness (1932), and Rain (1932).

After returning to Broadway and scoring rave reviews in

Dodsworth, he reprised his role for the 1936 film version of

the play and was nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award.

Huston was seen less on the screen in the later 1930s but

had a major triumph in All That Money Can Buy (1941), gar-

nering his second Academy Award nomination as Best Actor.

It was also in 1941 that Huston’s son, John, emerged as a hot

young writer-director with The Maltese Falcon, a film in which

the elder Huston made a cameo appearance as Captain

Jacoby, dying on Sam Spade’s couch with the falcon in his

arms. He also made a cameo appearance in Huston’s second

film, In This Our Life (1942).

By this time, Huston had settled into character parts, and

he could be seen to fine effect playing such roles as

JAMES

CAGNEY

’s father in Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), for which he

was honored with an

ACADEMY AWARD

nomination for Best

Supporting Actor, ambassador Joseph E. Davies in the ill-

fated Mission to Moscow (1943), and Ling Tau in Dragon Seed

(1944). Huston continued to give strong performances in

major hit films throughout the rest of the decade, shining in

such movies as And Then There Were None (1945), Dragonwyck

(1946), and Duel in the Sun (1947).

Modern audiences undoubtedly remember Huston best

for his role as the wise old prospector in his son’s classic The

Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). His performance

brought him a Best Supporting Oscar just three years before

his death in 1950. Huston’s last film was Furies (1950), but

his recorded talk-singing rendition of “September Song”

from the stage production of Knickerbocker Holiday became a

posthumous hit for the actor when it was used in the film

September Affair (1950).

See also

HUSTON

,

JOHN

.

Hutton, Betty (1921– ) A big, bright, brassy star—

mostly in musicals—over a 10-year period from 1942 to

1952, Hutton self-destructed, and her film career came to an

abrupt end. Hutton was known for her incredible exuberance

and energy, which earned her the nickname “The Blonde

Bombshell.” It was a moniker that had little to do with her

looks (which were fine) but a lot to do with her implacable

personality; she didn’t merely perform—she bulldozed.

Among her other nicknames were “The Huttentot” and

“The Blonde Blitz.”

Born Betty June Thornburg, she was the younger sister of

Marion (Thornburg) Hutton who later became a big-band

vocalist with the Glenn Miller orchestra. Their father died

when the sisters were young, and both girls were forced to

fend for themselves. Betty began by singing on street corners,

eventually becoming a band singer and then working her way

into vaudeville. Broadway beckoned and Hutton made her big

breakthrough as the star of the stage musical Panama Hattie in

1940. Paramount took notice and signed her to a contract.

Her first film was The Fleet’s In (1942), in which she filled

a supporting comic-relief role. She scored with audiences and

critics as a man-crazy female, a role she played in a string of

musicals, such as Star Spangled Rhythm (1942), Happy Go Lucky

(1943), and Here Come the Waves (1944). Hutton proved that

she did not need to sing in films to succeed when she starred

with her long-time costar Eddie Bracken in

PRESTON

STURGES

’s classic comedy The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek

(1944). Then she went a step further, proving her ability as a

dramatic actress by playing the once famous nightclub impres-

sario Texas Guinan in the hit movie Incendiary Blonde (1945).

Hutton’s career slowed down in the later 1940s, with just

a few memorable films, including her

BIOPIC

about the silent

serial queen Pearl White, called The Perils of Pauline (1947).

Dream Girl (1948) and Red, Hot and Blue (1949) followed.

Finding the right roles for a talent such as Hutton’s was not

an easy task, but the ideal vehicle came along when Judy Gar-

land was forced to drop out of Annie Get Your Gun (1950) due

to illness. Paramount loaned Hutton to MGM for the film,

and she scored a major triumph.

HUTTON, BETTY

214

The irrepressible Betty Hutton was known as the Blonde

Bombshell and for good reason, as seen here.

(PHOTO

COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

MGM wanted to buy her contract but Paramount had

plans of their own for their new superstar. She was teamed

with

FRED ASTAIRE

in Let’s Dance (1951), and Paramount

gave her the lead in its biggest film of 1952, Cecil B.

DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth. It was yet another hit,

winning a Best Picture Oscar. With her career at its height,

Hutton followed her success with a musical-star turn in

Somebody Loves Me (1952), the story of vaudeville star Blos-

som Seeley.

Then disaster struck. Hutton married her choreographer,

Charles O’Curran, and demanded that he be made her direc-

tor. Paramount said no, and Hutton walked. She broke her

contract, and her Hollywood fame and fortune came to a

dead stop. She didn’t appear in a movie again for another five

years and then only in a small, overlooked film called Spring

Reunion (1957). She performed ably in it but didn’t elicit any

other offers.

Plagued by four unsuccessful marriages, a drug problem,

fights with managers, and, finally, bankruptcy, Hutton slid from

nightclub work to stock production to a failed Broadway come-

back to walking out on a low-budget western in 1966. In 1974,

she was discovered working as a housekeeper in a Catholic rec-

tory in Rhode Island. Later, she took a job as a hostess at a Con-

necticut jai-alai complex. Eventually, in a daring and nostalgic

move that brought theater audiences to their feet, she returned

to Broadway in 1980 for three weeks to replace the vacation-

ing Alice Ghostley as Mrs. Hannegan in the hit musical Annie.

The thunderous applause and warm critical attention she

received had little effect on her; she returned to working for

the Catholic Church, and little has been heard from her since.

HUTTON, BETTY

215

Ince, Thomas H. (1882–1924) A writer, director, and

producer who was a seminal figure in the development of

film production. A contemporary of

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

, Ince

was a shrewd and talented filmmaker who insisted that fully

written shooting scripts be prepared rather than the custom-

ary rough outlines from which directors improvised. In addi-

tion to his tight supervision over the preparation of

screenplays, he also oversaw the work of other directors and

editors, establishing the position of studio production chief,

which would become the norm during the studio system’s

golden era. Thanks to his penchant for planning and efficient

organization, Ince, as both a director and later as Holly-

wood’s first true producer, made many of the early industry’s

best paced, most tightly made movies.

Born Thomas Harper Ince to a show-business family, he

began to act at the age of six. When he grew older, Ince

aspired to an acting career in theater, but the often out-of-

work thespian appeared in the movies as early as 1906 when

he acted in Seven Ages. In 1910, without any prospects for

success on the stage, he finally succumbed to the lure of

motion pictures and, like D. W. Griffith, began to act regu-

larly in front of the camera.

Shortly thereafter, he had the good fortune to begin his

directorial career, making several films that starred

MARY

PICKFORD

, among them Their First Misunderstanding (1910)

and Artful Kate (1911). He learned his trade well and soon

developed a reputation for making fluid, fast-placed, realistic

movies—many of them westerns. Ince also developed a rep-

utation as a smart showman who spared no expense to give

his films a high production gloss. He had a studio built in Los

Angeles that covered 20,000 acres, and hired a Wild West

show for his westerns.

Within two years, Ince was so busy that he finally began

to supervise other directors, rarely directing films himself.

He prepared scripts in great detail for his subordinate direc-

tors and made sure that they followed his orders explicitly.

When he did produce and direct his own films, the results

were often thrilling, as was the case with his version of

Custer’s Last Fight (1912) and Civilization (1915), an epic that

won more plaudits and more patrons than Griffith’s Intoler-

ance (1916).

In one of the more ironic twists of fate in early Hollywood,

three great filmmakers of the era, Thomas Ince, D. W. Grif-

fith, and

MACK SENNETT

found themselves working for the

same company, Triangle Film Corporation, in 1915. Ince’s

production methods were put into effect, with all three heavy-

weights largely supervising the busy output of the studio. Tri-

angle failed due to the hiring of high-priced Broadway stars

who were unknown outside of New York. Even Ince’s produc-

tion methods could not save the company from insolvency.

Ince left Triangle and continued producing movies with

excellent critical and commercial results throughout the rest of

the 1910s and early 1920s. Among his most notable achieve-

ments as a producer/director during this later era were Human

Wreckage (1923), Anna Christie (1923), and Idle Tongues (1924).

The idle tongues of gossipmongers certainly had occa-

sion to wag after the events of November 19, 1924. Thomas

Ince, then just 42 years old, died on William Randolph

Hearst’s yacht under extremely suspicious circumstances.

The official cause of death was listed as a heart attack induced

by acute indigestion, but rumor had it that Hearst shot Ince

because the producer was having an affair with his lover,

actress Marion Davies. An official investigation was launched

into the death, but no new evidence was uncovered; many

believed that Hearst’s power quashed any hope of the truth

being revealed.

It Happened One Night

FRANK CAPRA

’s 1934 sleeper

became the year’s biggest hit, swept the

ACADEMY AWARDS

216

I

(winning all five major Oscars, including Best Picture, Best

Director [Frank Capra], Best Screenplay [

ROBERT RISKIN

],

Best Actor [

CLARK GABLE

], and Best Actress [

CLAUDETTE

COLBERT

]), and changed Hollywood history.

The film was produced by Columbia, and therefore

HARRY COHN

accepted the film’s Best Picture Academy

Award. It was the only film ever to win all five top awards until

One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest was equally honored in 1975.

The movie, for all its impact, was a modest romantic

comedy about a spoiled, runaway heiress (Colbert) who falls

in love with a wisecracking, down-on-his luck reporter

(Gable) while traveling together with him on a long bus ride.

The film’s natural, idiosyncratic dialogue, the genuine sparks

between the macho Gable and the headstrong Colbert, and

location shooting that gave the natural feel of the open road

added immeasurably to the movie’s appeal. Capra’s uncanny

knack for telling a story with visual flair was very much in evi-

dence from the famous “Walls of Jericho” scene to the

equally famous hitchhiking sequence.

In his splendid autobiography, Frank Capra: The Name

Above the Title, the director explained how the movie came

into being. The film was based on a short story called “Night

Bus” by Samuel Hopkins Adams, which Capra read in Cos-

mopolitan while sitting in a barber shop. He had Columbia

buy the film rights to the story for $5,000.

As it happened, two previous bus-trip films had been

made by other studios, and both had been flops. Columbia

studio boss Harry Cohn ordered that the word Bus be

stricken from the title, and so the name of the film was

changed to It Happened One Night.

After repeated failures in signing up a female lead for the

film, Capra decided to go after the male lead in the hope of

getting a star whose presence in the cast would help attract a

formidable leading lady. MGM owed Columbia the use of

one of its stars, and though Capra asked for Robert Mont-

gomery, Montgomery refused. MGM’s L. B. Mayer forced

Columbia to take one of his up-and-coming actors, Clark

Gable, who was known to be demanding more money from

Mayer. The mogul tried to show Gable who was boss by

humiliating him and sending him to lowly Columbia on loan.

With Gable set for the film, Capra went after Claudette

Colbert for the female role because she was on vacation from

Paramount and could make her own deals without studio

interference. She won double her salary, receiving $50,000.

The film’s entire budget was a mere $325,000, with a

shooting schedule of four weeks. When the film opened, it

received only mildly positive reviews. But the word of mouth

on the film was stupendous. Every week, the crowds at the-

aters all over the country grew larger. Before long the film was

the talk of the industry, and critics went back to see the film

to find out what it was that they missed the first time around.

The film’s overwhelming success wrought great changes

in Hollywood. Columbia was catapulted into the ranks of

the major studios. Clark Gable’s supposed punishment

ended up turning him into MGM’s major male star, and

Louis B. Mayer had to triple the actor’s salary. From a film-

making perspective, the movie was significant because, in

script doctor Myles Connolly’s words, as reported by Capra,

“You [Capra] took the old classic four of show business—

hero, heroine, villain, comedian—and cut it down to three,

by combining hero and comedian into one person.” This

immensely important change in story and character struc-

ture has continued to this day.

Proving that lightning rarely ever strikes twice in the same

place, the film was remade in 1956 as You Can’t Run Away from

It with June Allyson and

JACK LEMMON

. It was not a hit.

IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT

217