Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

His movie career during the 1960s was marked by great

peaks and valleys. As was often to be the case, his best films

of the decade were comedies, including The World of Henry

Orient (1964), Throughly Modern Millie (1967), and his first

big blockbuster, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

The less-successful films were the dramas Toys in the Attic

(1963) and Hawaii (1966), a commercial and critical flop. In

an interesting footnote, Hill was temporarily fired from

Hawaii while the movie was in production, but the large

Polynesian cast refused to work for anyone but Hill and he

was quickly reinstated.

The 1970s were Hill’s golden period. With the clout that

came from directing Butch Cassidy, he was able to make what

many considered an “unmakeable” movie, Kurt Vonnegut’s

surrealistic Slaughterhouse Five (1972). This dark comedy was

well received by most critics, and it found a loyal, enthusias-

tic audience among young people. He followed that with the

most popular movie of his career, The Sting (1974). Once

again pairing Newman and Redford, this slick comedy caper

film brought Hill a Best Director Oscar while also winning

the Best Picture

ACADEMY AWARD

. At the time, it was also

the fourth–biggest-grossing movie in Hollywood history, just

behind The Godfather (1972), The Sound of Music (1965), and

GONE WITH THE WIND

(1939).

Hill continued to create seriocomic hits, although of a

more modest variety. Slap Shot (1977) was a controversial

comedy because it dealt with the violence and blood lust

inherent in the game of hockey. Critics didn’t know quite

what to make of it, but the film has become more highly

regarded in recent years. There was no controversy, however,

about A Little Romance (1979), a lovely film that has enjoyed

modest success. The director’s next movie, The World Accord-

ing to Garp (1982), received a mixed reaction both from

reviewers and audiences. Then came Hill’s straight dramatic

effort, The Little Drummer Girl (1984), which was dismissed

by the critics and spurned by audiences. In more recent years,

however, Hill went back to what he did best—comedy—fash-

ioning the highly regarded

CHEVY CHASE

vehicle Funny

Farm (1988), a movie that featured Hill’s particular talent for

combining commercial viability with comically pungent

observations on human behavior.

Hitchcock, Alfred (1899–1980) One of the cinema’s

greatest directors, he is known as the Master of Suspense. He

once remarked, “There is no terror in a bang, only in the

anticipation of it,” and the underlying tension in his movies

comes from placing ordinary people in extraordinary circum-

stances. The audience is made to relate almost palpably to his

characters’ anxieties, in part because of Hitchcock’s masterful

use of montage. How he intercuts a scene to emphasize what

is truly fearful creates suspense, heightening our awareness of

impending danger.

Ironically, his dark themes and striking visual style lent

themselves to such entertaining films that audiences and crit-

ics alike tended to dismiss their artistry. How could Hitch-

cock’s films be art, after all, if they were so much fun? Yet in

a 50-year directorial career that also included the producing

and scripting of many of his own films, Hitchcock proved,

beyond a shadow of a doubt, that his movies could withstand

the test of all art: time.

Born to a poultry dealer and fruit importer in England,

the middle-class Hitchcock received a rigorous Jesuit educa-

tion, eventually pursuing a career in electrical engineering,

but not ardently. He had studied art and, after taking the

transitional step of working in advertising as an artist, took

the plunge into filmmaking in 1920 as a title designer.

Hitchcock actually began his film career working for an

American firm, Famous Players–Lasky, which would later

become

PARAMOUNT PICTURES

. Not long after, however,

the company was taken over by a British concern and Hitch-

cock was given greater responsibilities. Soon he was involved

in all aspects of production, from art direction to screenwrit-

ing. Eventually, he was promoted from assistant director to

director, making his official debut in that capacity with The

Pleasure Garden (1925).

The director’s first thriller was The Lodger (1926), but he

would not become known for his work in the genre for nearly

another decade, although he made a splash with the sus-

penseful Blackmail (1929), Britain’s first all-talking picture.

Hitchcock made everything from musicals to romances,

finally finding his niche and sticking to it when he made The

Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). It was an international hit,

and he followed it with other thrillers, among them The

Thirty-Nine Steps (1935), Sabotage (1937), and The Lady Van-

ishes (1938). By the second half of the 1930s he had become

England’s leading director, and that meant that Hollywood

had to have him.

DAVID O

.

SELZNICK

signed Hitchcock to a contract and

brought him to America. During the next 36 years, almost all

of which were spent making movies in America, Hitchcock

built and enhanced his reputation as an immensely talented

storyteller, provoking a lively debate as to whether his Eng-

lish or his Hollywood period was best. To most observers,

though, there can be no doubt as to the answer; Hitchcock

reached the height of his powers in Hollywood, especially

during the 1950s.

It didn’t take long for the director to win the respect of

his peers. His very first Selznick film, Rebecca (1940), brought

Hitchcock the first of his five Best Director

ACADEMY

AWARD

nominations. Regrettably, he would never win an

Oscar, although he was later honored with an Irving Thal-

berg Award in 1967.

For the most part, the 1940s was a period of experimen-

tation for Hitchcock. Many of the films he made during the

decade were brilliant, and others were flops, but all were

interesting. Suspicion’s (1941) depiction of paranoia pushed

the audience to new limits; Shadow of a Doubt (1943) uncov-

ered evil in small-town America like no other film before;

Lifeboat (1944), a cinematic tour de force of montage,

rhythm, and pacing—the camera was confined to a small

lifeboat for virtually the entire length of the film—brought

him a second Oscar nomination; Spellbound (1945) allowed

him to experiment with dream sequences and gave him his

third Academy Award nomination; Notorious (1946), a sexu-

ally charged tale of masochism, was daring even for the

FILM

HITCHCOCK, ALFRED

198

NOIR

era; and Rope (1948), filmed in such a way as to make it

appear as if there were no cuts in the action at all, was a fas-

cinating novelty then as now.

Rich and provocative as Hitchcock’s work was in the

1940s, he surpassed himself in the 1950s, directing many of

his greatest films, including Strangers on a Train (1951), Rear

Window (1954, for which he garnered his fourth Oscar nom-

ination), To Catch a Thief (1955), The Man Who Knew Too

Much (1956, a remake of his own earlier film), Vertigo (1958),

and North by Northwest (1959). In these films he refined his

earlier themes, crystallizing the sense of corruption that is

part and parcel of the human condition.

In 1960 Hitchcock won his fifth and last Oscar nomina-

tion for the classic suspense thriller Psycho, a film that influ-

enced the showering habits of a whole generation.

Unfortunately, the rest of the 1960s was more problematic

for the director. He made fewer films, most of which were

neither critically nor commercially successful. After The

Birds (1963), which was a hit despite mixed reviews, Marnie

(1964), Torn Curtain (1966), and Topaz (1969) were not

immediately appreciated.

Finally, though, Hitchcock returned to his usual mold

in the 1970s to make two more films, Frenzy (1972) and

Family Plot (1976), both of which displayed a macabre sense

of humor, playful use of film techniques, and edge-of-the-

seat suspense.

The two actors who are most associated with Hitchcock

are

JAMES STEWART

and

CARY GRANT

, both of whom

appeared quite often in the master’s films during the 1940s

and 1950s. But despite their excellent performances in

Hitchcock’s films, he was not an actor’s director. He thought

of actors as “cattle” who were merely to be manipulated on

the set just as the audience’s emotions were to be manipulated

in the movie theater. Actors merely had to do what they were

told; he wasn’t interested in their interpretations of their

roles. Before filming even began, Hitchcock already knew

who his characters were.

The director was famous for having planned every shot of

his films in advance, drawing them on storyboards. As a con-

sequence, he was often bored during filming, figuring the

movie was essentially finished, except for the nuisance of

actually having to shoot it. One of the happy results of his

filmmaking system was that there was so little extra film shot

that producers couldn’t edit a Hitchcock movie in any other

way except as it was designed; he left no room for alternatives

in the cutting room.

There has never been a director whose image was more

well known than that of Hitchcock. That familiarity was

due in part to his two long-running TV series, Alfred Hitch-

cock Presents (1955–61) and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour

(1962–65), both of which featured the rotund director as

the on-camera host. (He did, in fact, direct as much as 12

hours worth of shows.) But Hitchcock had already been

introduced to viewers thanks to cameo appearances in his

own films, a tradition that began with The Lodger in 1926

when he helped fill out an insufficiently peopled crowd

scene. When the film was a hit, superstition took hold, and

he appeared in subsequent films until he became a steady

feature—audiences seeking him out and he finding amusing

ways to enter and exit scenes.

The director died in 1980.

See also

DE PALMA

,

BRIAN

;

HERRMANN

,

BERNARD

;

LEIGH

,

JANET

.

Hoffman, Dustin (1937– ) A character actor and star

since the late 1960s, Hoffman is talented, adventurous in his

choice of roles, and fully dedicated to his craft. A perfection-

ist, directors and producers have often referred to him as “dif-

ficult,” but his perfectionism has paid off in a great many

unique and often exhilarating film portrayals. In the course of

his first 18 starring roles, Hoffman garnered six Academy

Award nominations as Best Actor, winning the Oscar twice.

Hoffman was not, as legend has it, named for the silent-

screen cowboy star Dustin Farnum. His mother merely liked

the name Dustin and gave it to her son. There was, however,

an early family connection to the movies. His father was a

one-time prop man at

COLUMBIA PICTURES

, and the film

business always loomed large in the young Hoffman’s con-

sciousness. In fact, his older brother, Ronald, briefly broke

into the movies as a child actor playing a tiny role in

FRANK

CAPRA

’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Hoffman was originally interested in a music career,

enrolling at the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. But his

acting experiences in school plays made him rethink his

decision, and he switched career paths, first studying at the

Pasadena Playhouse, then coming to New York, and endur-

ing five rejections from the Actors Studio before finally

being admitted.

His success was long in coming. He supported himself

with an assortment of jobs, such as weaving Hawaiian leis,

working in a mental institution, and the ever-popular waiting

on tables. Meanwhile, he slowly made his reputation in the

theater with roles in such productions as Harry, Noon, and

Night, The Journey of the Fifth Horse (for which he won the

coveted Obie Award), and Eh? His success in the last of these

led to his first film role, in The Tiger Makes Out (1967), for

which he received 19th billing. Soon thereafter he played the

lead in a low-budget Spanish/Italian coproduction, Madigan’s

Millions, a film that wasn’t released in the United States until

1970, after both Hoffman and another actor in the movie,

JON VOIGHT

, became big stars.

Eh? also led to the biggest break in Hoffman’s career.

Director

MIKE NICHOLS

saw him in the show and decided to

cast him in his new film, The Graduate (1967). Hoffman was

paid $17,000 to play Benjamin Braddock in what became a

blockbuster hit, instantly establishing Hoffman as a major

new star and bringing him the first of his Oscar nominations.

He proved his success was not a fluke by wowing the crit-

ics and the public with his portrayal of Ratso Rizzo in Mid-

night Cowboy (1969), garnering yet another nomination as

Best Actor. Hoffman might have been a star with a loyal fol-

lowing, but he didn’t choose conventional starring roles.

Except for the contemporary love story John and Mary

(1969), he has played such characters (in starring roles) as the

121-year-old Jack Crabb in Little Big Man (1970), the nerdy

HOFFMAN, DUSTIN

199

prisoner who befriends the

STEVE MCQUEEN

character in

Papillon (1973), and a down-on-his-luck ex-con in Straight

Time (1978).

The mid-1970s was Hoffman’s most consistently suc-

cessful period. Among the top box-office films in which he

gave winning performances were the controversial

SAM

PECKINPAH

movie Straw Dogs (1972); his Oscar-nominated

portrayal of Lenny Bruce in Bob Fosse’s Lenny (1974); the

real-life political thriller in which he played Carl Bernstein,

All the President’s Men (1976); and his last hit of the 1970s,

Marathon Man (1976).

Having been nominated several times for Academy

Awards, the actor was overdue when he finally won his Oscar

for Kramer vs. Kramer (1980). Had Ben Kingsley not taken

the statuette for Gandhi in 1982, Hoffman might have won

again for his tour de force in Tootsie (1982), one of the actor’s

most successful movies.

After Tootsie, he was not seen on the big screen for several

years, having a smash success on Broadway as Willy Loman

in an acclaimed revival of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman,

a production that was later adapted for television, with Hoff-

man recreating his role. When he finally returned to the

movies, however, it was in the $50 million megaflop Ishtar

(1987). Neither Hoffman nor his costar

WARREN BEATTY

were big enough box-office draws to compensate for the neg-

ative press of this mediocre comedy. But Hoffman quickly

recouped in 1988 when he played the autistic savant brother

of

TOM CRUISE

in Rain Man, a film that brought Hoffman his

second Best Actor Oscar.

Hoffman performed a number of memorable smaller roles,

such as Mumbles in

WARREN BEATTY

’s Dick Tracy (1990). In

1991 he played Captain Hook in

STEVEN SPIELBERG

’s Hook,

and in 1999 Hoffman played the mysterious messenger or

ministering angel or metaphysical shrink in Luc Besson’s gory,

seraphic, and loopy The Messenger: Joan of Arc (1999).

Among Hoffman’s best movie roles during the 1990s was

his performance as Walter “Teach” Cole in the film adapta-

tion of David Mamet’s American Buffalo (1995). Hoffman ear-

lier played gangster Dutch Schultz effectively in the Robert

Benton adaptation of the E. L. Doctorow novel Billy Bathgate

(1991). In Hero (1992) Hoffman helped director Stephen

Frears satirize the state of television news by playing Bernie

LaPlante, a crook facing jail time for dealing in stolen goods

but nonetheless the real “hero”—he leads 54 airplane crash

survivors to safety, though the Andy Garcia character gets the

credit because he looks the part of a hero.

The same emphasis on the role of television and the

media is found in Mad City (1997), in which Hoffman plays a

journalist exploiting a hostage situation to further his career,

directed by the political master, Constantin Costa-Gavras.

That same year, Hoffman was nominated for the Best Actor

Oscar in his role as a neurotic and ambitious television pro-

ducer who cooperates with the military establishment to cre-

ate the appearance of a real war in the Balkans in

BARRY

LEVINSON

’s Wag the Dog (1997). That same role won him a

Golden Globe award. In 1999, for the first time, Hoffman

produced a film in which he did not appear, A Walk on the

Moon, but this was a commercial disappointment. Also in

1999, Hoffman received the Lifetime Achievement Award

from the American Film Institute.

Holden, William (1918–1981) An actor who became

one of Hollywood’s leading romantic sex symbols of the

1950s, his career spanned more than 40 years and nearly 70

starring roles. He brought a virile humanity to his perform-

ances that satisfied the public even when his films did not.

With his tall, athletic physique and open-faced good looks,

there was something likable about Holden, even when he

played cynics and soreheads.

Born William Franklin Beedle, Jr., he came from a well-

to-do family. He went to Pasadena Junior College with the

expectation of studying chemistry and joining his father’s

chemical company, but while in school he was spotted by a

Paramount talent scout and given a standard seven-year con-

tract. His first film appearance was as a member of a road gang

in Prison Farm (1938). After just one more bit part in the

BETTY GRABLE

musical Million Dollar Legs (1939), he won the

role of the boxer/violinist in Golden Boy (1939). Despite his

lack of acting polish, the film was a moderate success and

though Holden didn’t become a major star, he did jump from

bit player to leading juvenile actor virtually overnight.

More than most actors, Holden had to learn on the job.

After Golden Boy, he appeared in supporting roles in films

such as Invisible Stripes (1940) and Our Town (1940) as he con-

tinued to learn his craft. His career improved steadily, if

unspectacularly, in films such as Arizona (1941), I Wanted

Wings (1941), and Texas (1941). At this time, he married

actress Brenda Marshall, a union that lasted until their

divorce in 1970. After starring in a few more minor films, he

enlisted in the army in 1942, the first married star to join up.

He didn’t appear in Hollywood film again until 1947,

when he starred in Blaze of Noon. He worked steadily there-

after, but he neither excited film fans nor critics until he filled

in for

MONTGOMERY CLIFT

, who was supposed to star in

BILLY WILDER

’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). The film was not a

box-office hit, but it was critically acclaimed, and Holden

finally established himself as a reputable actor with the added

bonus of a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his performance

in the film.

Holden reached the peak of his career during the 1950s.

Not long after Sunset Boulevard reached movie theaters, he

was in another big hit, Born Yesterday (1950), a movie that

made fun of Holden’s studio boss,

HARRY COHN

. But the true

turning point in Holden’s path to major stardom was his

tough, cynical performance in Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17 (1953).

This time Holden was not only nominated, but he won the

Academy Award for Best Actor.

With exceptions, Holden appeared far more regularly in

excellent films, such as the Hays Code-challenging The Moon

Is Blue (1953), Sabrina (1954), The Country Girl (1954), The

Bridges at Toko-Ri (1955), Love Is a Many Splendored Thing

(1955), Picnic (1956), and the biggest blockbuster of them all,

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). In many of these films,

Holden played lovers, cads, and the occasional reluctant

hero. Considering that the 1950s represented a period of

HOLDEN, WILLIAM

200

marked decline in Hollywood, Holden’s long string of hit

films was particularly impressive.

His film success began to diminish slowly during the late

1950s and early 1960s. Though he worked steadily, he didn’t

have a hit in more than a decade. His star status and credibil-

ity as an actor were saved by a strong, convincing perform-

ance as Pike Bishop in

SAM PECKINPAH

’s controversial film

The Wild Bunch (1969). Holden’s career throughout the

1970s was full of ups and downs. The actor seemed more

interested in his conservation work in Africa than in the

movies, but he managed a sensitive performance in the flop

Breezy (1973) and was effective as

FAYE DUNAWAY

’s lover in

the hit Network (1976). His last movie, S.O.B. (1981), a bitter

BLAKE EDWARDS

satire of Hollywood, was a fitting finale for

an actor who cared little for the industry.

Holden, who fought a drinking problem for more than 20

years, died of an alcohol-related injury in his home.

Holliday, Judy (1922–1965) A talented comedienne,

Holliday projected vulnerability even as she chewed up the

scenery in a series of brilliant performances in many of the

better comedies of the 1950s. Her appearance allowed her to

play both prim, repressed comic heroines as well as saucy,

femmes fatale. Although she starred in only seven films, with

noteworthy appearances in but four others, she had a consid-

erable impact in the course of a 10-year Hollywood career

that ended in her untimely death at the age of 43.

Born Judith Tuvim, she derived her stage name from

tuvim, which means “holiday” in Hebrew. Her first important

show-business break came when she teamed with

BETTY

COMDEN AND ADOLPH GREEN

to form a cabaret act. Later,

after a few small roles in films during the mid-1940s, Holli-

day gave up on Hollywood and concentrated on a Broadway

career, soon starring in the hit stage comedy Born Yesterday in

1946. She came to the attention of film audiences in 1949

when she played the comically addled murder suspect in the

hit Hepburn-Tracy vehicle, Adam’s Rib (1949).

Holliday lit up the screen in 1950 when she reprised her

role as Billie Dawn in Born Yesterday, playing the seemingly

vapid and common broad who has more upstairs than anyone

gives her credit for; her performance brought her an Oscar as

Best Actress. In spite of her success in films, she continued to

work as much on Broadway during the 1950s as she did in

Hollywood. Her screen credits during the 1950s included a

subtle and sensitive performance in the drama The Marrying

Kind (1952), followed by the comedies It Should Happen to You

(1954), Phffft (1954), The Solid Gold Cadillac (1956), Full of

Life (1957), and Bells Are Ringing (1960).

Hollywood Today, it is a somewhat seedy Los Angeles

suburb, bereft of its one-time glamour as the capital of the

movie world. But to most movie fans, past and present, Hol-

lywood—also known as the Dream Factory and Tinsel

Town—was never so much a place as a state of mind. Even

during Hollywood’s golden era of the 1930s and 1940s, the

studios were spread far and wide across the Los Angeles basin.

Hollywood was originally the name of a ranch that existed

on the site of the world’s future film mecca. It was owned

(and named) by a Mr. and Mrs. Wilcox, late of Kansas, who

had retired there in 1886. Mr. Wilcox had been a successful

real-estate man and he put his skill to work again in 1891

when he began to subdivide his ranch and sell homesites. In

1903, the sleepy little community was incorporated as a vil-

lage, taking the name of the ranch as its own.

Meanwhile, the American film industry was growing by

leaps and bounds in New York. It was, essentially, an East

Coast business. But in 1907, movie production on a small

scale began in the Los Angeles area when Colonel

WILLIAM

N

.

SELIG

began to shoot films there. The area of southern

California appealed to filmmakers for a variety of reasons:

Abundant year-round sunshine allowed more time to shoot

movies, and the wildly varied terrain was suitable for making

various genres of films outdoors. In 1908 when the Edison-

inspired Motion Picture Patents Company began to try to put

their competitors out of business, Southern California

became a haven for upstart film companies who were trying to

stay as far away from New York as they could. In addition, the

Mexican border was close by for a quick escape from the law.

Hollywood became part of greater Los Angeles in 1910

but was still a backwater. That changed dramatically when

CECIL B

.

DEMILLE

arrived in 1913 with the intention of mak-

ing his first movie there. He had planned to shoot his film in

Flagstaff, Arizona, but he didn’t care for the locale and kept

traveling by train until he reached the end of the line: Holly-

wood. There he made the feature-length hit The Squaw Man

(1914), and suddenly, thanks to DeMille (who is sometimes

referred to as the Father of Hollywood), filmmakers arrived

in droves. By the time the Motion Picture Patents Company

was dissolved in 1917, most major studios had come out to

the West Coast to make movies, keeping their business

offices in New York.

Despite the fact that the big studios had built their mas-

sive soundstages and back lots in places as divergent as the

San Fernando Valley and Culver City, Hollywood was the

name that stuck to describe the home of the movie business.

To movie audiences all over the world, the words Made in

Hollywood ensured the most opulent, most professionally

made, and most exciting movies available.

So it remained until the late 1940s and early 1950s when

the

STUDIO SYSTEM

finally ended. Forced to divest them-

selves of their movie-theater chains in an antitrust case and

suffering big box-office losses due to the newly expanding

television medium, studios began to crumble. Films that

would once have been routinely made in Hollywood were

now shot overseas for tax reasons. In addition, stars, direc-

tors, and producers became independents, merely renting

studio space to make their movies. Finally, the studios

became largely distribution networks rather than genuine

film producers. As this erosion took place, Hollywood’s

image as a film capital suffered.

Hollywood was saved by what had, at first, killed it: tele-

vision. The film industry’s soundstages and back lots con-

tinue to hum with activity today thanks to the steady

production of TV series and TV movies where once the great

HOLLYWOOD

201

classics of the silver screen were made. Yet, all these years

later, Hollywood remains a synonym for movie.

Hollywood Ten The 10 individuals who refused to testify

before the House Un-American Activities Committee

(HUAC) in 1947. Found in contempt of Congress, they were

all eventually sentenced to one year in jail and fined $1,000.

As a result, the Hollywood Ten became a symbol of the com-

munist witch-hunt mentality that swept through the enter-

tainment industry (and the rest of America) during the height

of the cold war in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Paranoia

concerning Russian intentions to undermine and destroy

American society led to a Hollywood purge of vast propor-

tions, with left-leaning actors, directors, and particularly writ-

ers, seeing their careers—and often their lives—destroyed.

Nine members of the Hollywood Ten—Alvah Bessie, Her-

bert Biberman, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard

Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, and Dal-

ton Trumbo—were blacklisted—locked out from all work in

the film industry—after they were released from jail. The 10th

member of the group, director Edward Dmytryk, broke while

in prison and agreed to cooperate with the committee, con-

fessing his past affiliation with the Communist Party and offer-

ing the names of others who had also been members.

A great many people in the entertainment industry during

the 1930s had seen communism as a viable form of govern-

ment during the Great Depression. A parade of friendly wit-

nesses, such as

STERLING HAYDEN

,

LLOYD BRIDGES

, Budd

Schulberg, and

ELIA KAZAN

, admitted their past involvement

in the Communist Party, rejected that past, and then told of

friends and associates who had been members of the party.

With rumors and accusations flying—many of them

unfounded—people who were named, and many who were

not (and who had no history as communists) were blacklisted.

HUAC returned to Hollywood in 1951 to continue its

highly publicized hearings, calling on a parade of famous

names to testify. It was a circus. Among those linked to the

Communist Party were Sidney Buchman, Jules Dassin, Will

Geer, Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Joseph Losey,

Abraham Polonsky, and

ROBERT ROSSEN

. It seemed as if any-

one was fair game. Among those testifying was author Ayn

Rand who went so far as to describe Louis B. Mayer, the right-

wing head of MGM, as being “no better than a communist.”

HUAC ran roughshod over Hollywood because everyone

in the industry was afraid of being labeled a “red” if they

spoke out against the committee. Eventually, however, in the

early 1950s, a courageous group of filmmakers, led by

JOHN

HUSTON

and

HUMPHREY BOGART

, publicly denounced

HUAC’s tactics and motives. But in the end, more than 1,000

people were smeared with the communist label and found

that they were unable to defend themselves; many didn’t even

know they were on the blacklist until they suddenly couldn’t

find work.

Among others, the blacklist effectively destroyed the act-

ing careers of Larry Parks and

JOHN GARFIELD

, forced such

directors as Joseph Losey and Jules Dassin to work in

Europe, and sent scores of writers such as Dalton Trumbo

into hiding, writing screenplays under assumed names and at

cut-rate prices. Trumbo, in fact, won an Oscar for his screen-

play of The Brave One (1956) under the name of Robert Rich!

At the movies, themselves, the red scare produced a spate

of films during these years that mirrored the paranoia of the

times. The most deeply right-wing of the lot was Leo

McCarey’s My Son John (1952), a film that detailed the hor-

ror a mother experiences on learning her son is a “commie.”

Although the western High Noon (1952) indirectly attacked

American reluctance to stand against the bullying of HUAC

and the red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy, the movies

generally kept a safe distance from material considered left

wing throughout the rest of the 1950s until the blacklist was

finally abolished.

Hollywood, which had been torn apart by the political

upheaval of the red-scare years, looked at its past in two mod-

ern films, The Way We Were (1973) and The Front (1976). The

latter film was particularly noteworthy because its director,

MARTIN RITT

, was a blacklist victim, as was one of its costars,

Zero Mostel.

See also

DOUGLAS

,

KIRK

.

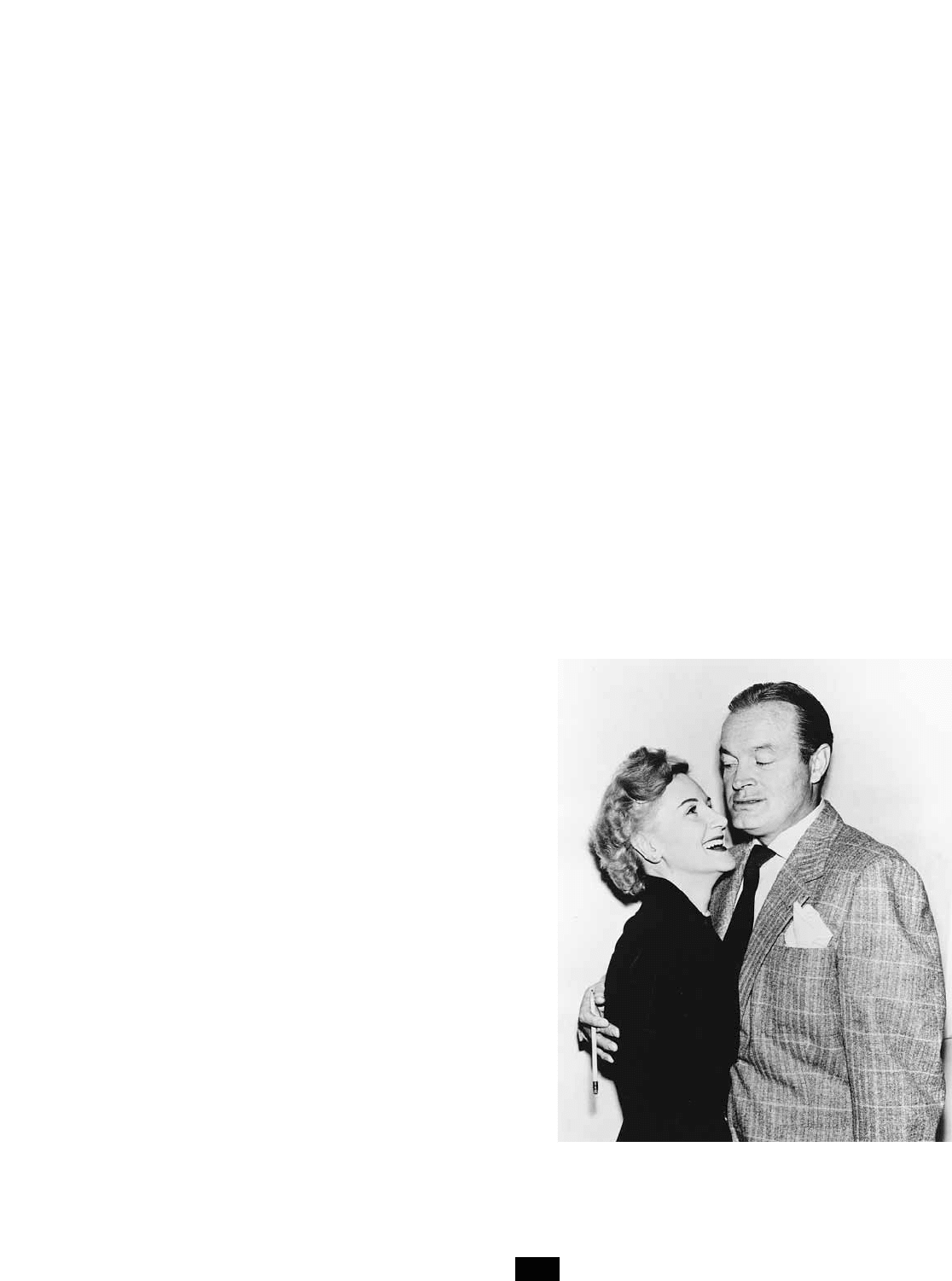

Hope, Bob (1903–2003) His screen character was usu-

ally that of a fast-talking, wisecracking con man who ran

scared at the first sign of trouble. He also thought he was

God’s gift to women and couldn’t understand why he never

HOLLYWOOD TEN

202

Bob Hope (PHOTO COURTESY AUTHOR’S

COLLECTION)

got the girl. From his solo hits to his legendary partnership

with

BING CROSBY

in the famous road movies, Hope fash-

ioned a remarkable film career that made him Hollywood’s

most successful comic actor for a period of nearly 15 years. It’s

also no accident that he has been admired and studied for his

comic timing by a great many subsequent film comedians,

including

WOODY ALLEN

.

Born Leslie Townes Hope in London, he and his family

immigrated to America and settled in Cleveland when he was

four years old. After winning several Charlie Chaplin imper-

sonation contests, he found the courage to try his hand at

vaudeville. Starting with “Songs, Patter and Eccentric Danc-

ing,” he eventually made his way to Broadway, appearing in

the hit show Roberta (1933).

Several other successful Broadway shows followed, and

his reputation as a comic actor led to his own radio show.

When Paramount decided to continue their series of Big

Broadcast movies with The Big Broadcast of 1938, they hired a

great number of radio personalities, including Hope. It was

his first film, and he acquitted himself well, singing with

Shirley Ross the song that was to become his theme, “Thanks

for the Memories.”

Hope continued in movies, participating in several

minor efforts until he made The Cat and the Canary (1939), a

funny horror film in which he began to perfect his special

brand of comic cowardice. The movie was a hit, but it was

just the beginning.

The 1940s, Hope’s richest decade in terms of hits and

quality comedies, began with his first teaming with Bing

Crosby and

DOROTHY LAMOUR

in the original road movie,

The Road to Singapore (1940). There were seven road movies

in all, and the Hope-Crosby team became one of the most

beloved duos in all of film comedy because it seemed as if the

two stars were having the time of their lives.

There is a tendency to forget the enormous number of

films Hope made because of his long television career begin-

ning in the 1950s. But he was a bona-fide movie star of long

duration who entered the top-10 list of money-makers in

1941 and stayed in the top 10 every single year until 1953,

with hits such as Monsieur Beaucaire (1945) and My Favorite

Brunette (1947). In 1949, he was voted the number-one box-

office star in the country, thanks to his hit comedy Paleface

(1948), with

JANE RUSSELL

.

In the mid-1950s, however, Hope’s film comedies began to

falter. Except for a few solid efforts such as The Seven Little Foys

(1955), Beau James (1957), and the last of the road movies with

Crosby, most of Hope’s movies of the latter 1950s and 1960s

were rather stale. By this time he had become more of a tele-

vision star than a film star. But if Bob Hope is an American

institution, the foundation of that institution was laid with his

classic comedies of the 1940s. See also

COMEDY TEAMS

.

Hopkins, Sir Anthony (1937– ) Philip Anthony Hop-

kins, born on New Year’s Eve, 1937, in Port Talbot, Wales,

paid his dues as a stage actor for many years in England

before breaking through to movie stardom. Thinking that he

might become rich and famous like fellow Welsh actor

Richard Burton, who had also grown up in Port Talbot, he

completed his course of study at the Cardiff College of Music

and Drama and then graduated from the Royal Academy of

Dramatic Art in 1963. Within two years,

SIR LAURENCE

OLIVIER

invited him to join the Royal National Theatre in

London, and within five years he landed his first film role in

The Lion in Winter (1968). Hopkins left the National Theatre

in 1973, married Jennifer Lynton, a film production assistant,

and moved first to New York and then to California. There

he found roles in A Bridge Too Far (1977), Magic (1978) (in

which he played a ventriloquist controlled by his evil

dummy), and, most impressively, The Elephant Man (1980),

directed by David Lynch.

After 10 years in America, Hopkins returned to the Lon-

don stage in 1984, where he won rave notices in 1985 play-

ing Lambert le Roux, the Rupert Murdoch–like publishing

tycoon in the play Pravda, by David Hare and Howard Bren-

ton. The play was such a hit that it was revived in 1986 with

Hopkins still in the lead. But an even more demanding role

awaited him in Hollywood, a role that would make him an

unforgettable superstar.

Hopkins took the role of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence

of the Lambs in 1992 and made it so thoroughly his own that

most people forgot that it had been played differently by

Brian Cox in Manhunter (1986). So astonishing was this cre-

ation that Hopkins earned an Academy Award as Best Actor.

He would go on, of course, to play Lecter in the unpleasant

sequel, Hannibal (2001). When a novelist once complained to

David Hare that “Tony seems to have no way of controlling

his emotions,” Hare responded, “He does have a way. It’s

called acting.” Nobody has done it better in a wide variety of

roles—a sinister Claudius for Tony Richardson’s Hamlet

(1969), an overly uptight butler in Remains of the Day (1993),

for which he received the British Academy Award as Best

Actor, an anguished president coming apart at the seams in

Oliver Stone’s Nixon (1995), a campy and flamboyant Van

Helsing in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), a gentle bookseller

in 84 Charing Cross Road (1986), a disturbed artist in Surviv-

ing Picasso (1996), a murderously jealous husband in The Edge

(1997), a murderously angry avenging father in Titus (1999),

an inquisitive publisher in Chaplin (1992), and a compassion-

ate writer in Shadowlands (1993). Truly, no role, however seri-

ous or silly, seemed beyond his reach. He was knighted in

1993. Sir Anthony was in top form as Lecter in 2002 in the

Silence of the Lambs prequel, Red Dragon.

Hopper, Dennis (1936– ) The wayward actor and

director whose film career has been subject to steep peaks and

deep valleys. Known to have been an obstinate young actor

early in his career, he became a director notorious for his drug

use. Perhaps best known for having directed, coscripted, and

costarred in

EASY RIDER

(1969)—a landmark movie that tem-

porarily changed the face of Hollywood—Hopper later

emerged in the 1980s from a hell of his own creation to shine

as a brilliant character actor and imaginative director.

Hopper thought he was hot stuff until he met

JAMES

DEAN

on the set of Rebel without a Cause (1955). Hopper

HOPPER, DENNIS

203

played Goon, a minor character in that classic film, but

found himself mightily impressed with Dean and his

“method” style of acting. Hopper continued to appear in

minor roles, including one in Dean’s Giant (1956). Hopper

displayed his own rebelliousness while filming From Hell to

Texas (1958) when he refused to play a scene as ordered by

veteran director

HENRY HATHAWAY

. In a famous test of wills,

Hopper finally relented after an incredible 85 takes. Word of

Hopper’s stubbornness spread quickly through the film

industry, and he soon found himself persona non grata in

Hollywood—at least until he married Brooke Hayward, the

daughter of actress Margaret Sullavan and top film agent

Leland Hayward.

By virtue of his wife’s connections, Hopper began to

appear in movies again (even those of Henry Hathaway),

including The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), Cool Hand Luke

(1967), Hang ’Em High (1968), and True Grit (1969). He had

small roles in the Hollywood establishment movies but lead-

ing roles in teen exploitation films such as Queen of Blood

(1966), The Trip (1967), and The Glory Stompers (1967). His

marriage to Hayward ended in 1969.

Itching to direct, Hopper talked fellow actor Peter

Fonda into producing a motorcycle movie that the pair

eventually cowrote and starred in. Made for $370,000, Easy

Rider grossed more than $40 million. Hopper had proven

that an independently made movie directed at the baby-

boom generation could be a huge commercial success,

prompting studios to scramble to give young filmmakers

the opportunity to make youth-oriented movies, most of

which failed. Hopper’s next film, The Last Movie (1971),

funded by a major studio, went way over budget and, due to

Hopper’s drug use, was virtually incomprehensible when

finally edited.

Hopper drifted through the 1970s in a fog, occasionally

appearing in foreign films, most memorably in Wim Wen-

ders’s The American Friend (1977).

In the early 1980s, he began to clean up his act. He

appeared in Rumble Fish (1983) and directed Out of the Blue

(1983), a film that did not repeat the earlier movie’s stunning

success. Hopper relapsed and was ultimately committed to a

mental hospital, where he finally kicked his drug and alcohol

dependencies. Since then, he has been nothing short of

astonishing, winning an Oscar nomination as Best Support-

ing Actor for his evocative performance in Hoosiers (1986)

and gaining raves for his acting in Blue Velvet (1986) and

River’s Edge (1987). He also finally hit the top again as a

director with the critically acclaimed Colors (1988).

Since then Hopper has directed three other films—Back-

track (1989), The Hot Spot (1990), and Chasers (1994). He has

been much more active as an actor, appearing in about 20

films since 1990, many of them crime stories often involving

drugs. In 1991, he played drug smuggler Barry Seal who

turned DEA informant in Double Cross. In the next year he

played a cop seeking revenge for his partner’s death at the

hands of drug dealers; in 1993 he was a sleazy ex-con who

owes the mob money in Boiling Point; and in The Last Days of

Frankie the Fly (1996), he played an overreaching petty thief

in Los Angeles.

The best of these roles was as the real killer in Red Rock

West (1993), a

FILM NOIR

set in Wyoming. Hopper has also

played a number of offbeat roles, such as the Philistine gen-

eral in the TNT production of Samson and Delilah (1996), a

self-help guru in Search and Destroy (1994), and a “space

trucker” in Space Truckers (1997), in which he is called on to

transport containers to Earth. Perhaps his most interesting

role of this sort was in Super Mario Bros. (1993), based on the

Nintendo game. In the film, he does a parody of his Frank

Booth role in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986).

Hopper, Hedda See

GOSSIP COLUMNISTS

.

Horne, Lena See

RACISM IN HOLLYWOOD

.

horror films In their purest sense, movies based on the

sinister supernatural or on events that occur when “man

meddles in things better left untouched.” Therefore, scary

science fiction films, such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers,

movies about creatures from a prehistoric past such as King

Kong, and psychological suspense movies such as Psycho, are

not classified here as horror films. But horror does include

just about everything else capable of raising goose bumps.

The horror film is not a distinctly American genre in the

way the western and gangster films are. While the German

Expressionists, for example, were making sophisticated hor-

ror films such as The Golem (1914), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

(1919), and Nosferatu (1921), filmmakers in the United States

made only the rare horror movie, such as John Barrymore’s

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920).

In fact, it wasn’t until the 1920s that Hollywood even

began to compete with the Europeans in the lucrative horror

market. While there were, for instance, many Hollywood

comedy stars of the silent era, there was only one true horror

star:

LON CHANEY

. He specialized in the macabre and the

horrific, making movies such as The Phantom of the Opera

(1925) and The Monster (1925).

Soon after the talkie revolution, Hollywood reigned

supreme in the horror genre, and yet, even after doing so, the

horror film quickly became a Hollywood stepchild, reduced

to “

B

”

MOVIE

status and rarely taken seriously as a means of

cinematic expression.

Nonetheless, when the horror film was suddenly revived

in 1931 with the presentation of Tod Browning’s Dracula

starring

BELA LUGOSI

, Hollywood took notice. The movie

was a sensation, assuring a spate of sequels that have con-

ferred a certain cinematic immortality that not even a cellu-

loid spike could end. Lugosi often reprised his role as the

vampire, and he was not the only actor to do so.

Lugosi might have gone on to even greater fame had he

not turned down the role of Frankenstein (1931), giving

BORIS

KARLOFF

his chance at stardom. Frankenstein, directed by

JAMES WHALE

, was just as big a hit as Dracula had been, and

these two films formed the basic core of all future Hollywood

horror films. In fact, Lugosi and Karloff became a virtual

HOPPER, HEDDA

204

two-man horror acting unit, often appearing together in the

same movies.

Both Dracula and Frankenstein had been made at Univer-

sal Studios. Just as Paramount was known for comedies,

Warners for gangster films, and MGM for romantic gloss,

Universal in the 1930s was known for its horror films.

The golden period of the horror film was certainly the

early to mid-1930s. Tod Browning and James Whale contin-

ued directing horror films, creating some of the genre’s best,

such as Browning’s Freaks (1932) and Whale’s The Invisible

Man (1933) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). They were

joined by other directors such as

KARL FREUND

, who made

The Mummy (1932), and

ROUBEN MAMOULIAN

, who directed

the definitive version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932), star-

ring

FREDRIC MARCH

in an Oscar-winning role (remade with

SPENCER TRACY

in the title role in 1941). But the genre was

already petering out by 1935, when Stuart Walker directed

Werewolf of London (1935).

By the latter 1930s, the genre was already declining with

inferior sequels and remakes. The slide was halted in the

early 1940s by producer

VAL LEWTON

at RKO who was

responsible for a number of low-budget but atmospheric

horror films such as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a

Zombie (1943).

The familiar 1930s horror characters were eventually

lampooned in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

The film was both funny and scary—as well as hugely popu-

lar, leading to its own inferior sequels in which

ABBOTT AND

COSTELLO

met the Invisible Man (1951), Dr. Jekyll and Mr.

Hyde (1953), and so on.

By this point it might have appeared that the horror film

was dead, and by the early 1950s, it also seemed as if Holly-

wood was dead. In the search to bring people back into the-

aters, 3-D was offered to the public, which enjoyed the

novelty, and there was no better effect with which to scare

people than 3-D; for example, a slimy hand seemingly

extended into the audience had a frightening effect. It is no

wonder, then, that 3-D movies such as a remake of House of

Wax (1953) and The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954)

brought the horror movie back with a vengeance.

By the late 1950s,

AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL PICTURES

and their prime director,

ROGER CORMAN

, had taken up the

torch of the horror film. They made their movies fast and

cheap—and usually it showed. Films such as I Was a Teenage

Werewolf (1957) starring Michael Landon were directed

specifically to the teenage drive–in-theater market. Corman

ultimately made a series of movies starring

VINCENT PRICE

that were based on the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. These

films, such as The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) and The Raven

(1963), lifted the A.I.P. films to a stylized, campy height that

most latter-day horror films have never quite achieved.

The violent, gory horror film had its birth in 1968 when

GEORGE ROMERO

made his now classic Night of the Living

Dead in Pittsburgh with an unknown cast and a minuscule

budget. Based on the success of that shocking movie, the

1970s and 1980s witnessed a boom in the horror genre with

enormous hits such as Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th

(1980), plus all of their respective bloody spawn.

The horror movie wasn’t entirely relegated to the

exploitation market. The 1970s and 1980s saw some big-

budget “

A

”

FILM

s in this area, such as The Exorcist (1973),

The Omen (1976), and Poltergeist (1982). But even these seri-

ous, successful films were followed by exploitive poorly done

remakes.

The acknowledged masters of the horror film in the

1990s were the veterans Wes Craven and

JOHN CARPENTER

.

Craven did two Scream films back to back (1996 and 1997)

and also made Vampire in Brooklyn (1995), Wes Craven’s New

Nightmare (1994), The People under the Stairs (1991), and Wes

Craven Presents: Dracula (2000); Scream 3 was also released

that year. John Carpenter’s horror films during the 1990s

included Body Bags (1993), In the Mouth of Madness (1995),

Village of the Damned (1995), and John Carpenter Vampires

(1997). Notice that publicists included both Carpenter and

Craven’s names in the titles as a horrible inducement. The

trend continued with Stephen King.

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) was directed by

Jim Gillespie, imitating the directors mentioned above, and

the picture, however derivative, grossed $70 million. It was

therefore followed by I Still Know What You Did Last Sum-

mer, directed by Danny Cannon in 1998, which made a more

modest $40 million. Independent filmmakers scored with

the low-budget Blair Witch Project in 1999, which grossed an

impressive $141 million. Joe Dante inaugurated the Howling

series of werewolf movies in 1981, and it continued through

Howling 7 in 1995. A more sophisticated approach to the

werewolf genre was Mike Nichols’s Wolf (1994), starring

JACK NICHOLSON

.

It seemed inevitable that Stephen King, the master of the

horror novel, would venture into filmmaking. In fact he

wrote and directed his own version of The Shining for televi-

sion in 2002 because he did not approve of Stanley Kubrick’s

1980 version. The King version is hardly better. Other

notable horror movies have included The House on Haunted

Hill (1999), The Sixth Sense (1999), Final Destination (2000),

Jeepers Creepers (2001), The Others (2001), The Ring (2002), 28

Days Later (2003).

There isn’t another genre that has so fed upon itself as

horror. Any creature, monster, or supernatural apparition

that succeeds on screen is bound to return time and again. Yet

there is something comforting about the recycled nature of

the horror film. The images of Dracula, the Mummy, and

Frankenstein are part of our collective nightmares, and their

continuing permutations in the movies let us know with a

(dread) certainty that there is always something out there in

the dark waiting to grab us and make us scream. Horror on

film has been especially effective because movies are so simi-

lar to dreams; the best of them are nightmares that we expe-

rience with our eyes wide open in a dark theater.

Houseman, John (1902–1988) A renaissance man who

successfully wrote, produced, and directed entertainments in

radio, theater, and film. Late in life, Houseman became an

Oscar-winning actor and a highly recognized personality. He

was involved in the writing of two motion pictures, one of

HOUSEMAN, JOHN

205

them an unequaled masterpiece. As a producer, he has been

associated with a great many quality movies of the late 1940s

and 1950s.

Born Jacques Haussmann to a prosperous Alsatian father

and an English mother, he was educated in England and

arrived in New York in the mid-1920s to represent his

father’s grain business. Not long after coming to America,

Houseman began his increasingly influential work in the the-

ater, at first translating German and French plays into Eng-

lish, and soon writing, directing, and producing plays directly

for the stage—with considerable success.

His story took a fateful turn when Houseman befriended

the “boy wonder”

ORSON WELLES

. Together, they founded

the famous Mercury Theater in 1937. They also worked

together in radio, including the historic Halloween eve

broadcast of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds.

Unbeknownst to most,

CITIZEN KANE

(1941) was not

Orson Welles’s first movie. Houseman produced and had a

small role in Too Much Johnson (1938), a film Welles never

completed. In any event, Houseman’s influence on Welles’s

masterpiece, Citizen Kane, was also significant. Though

uncredited, he helped devise the story and he supervised the

script revisions. Unfortunately for Welles, their fruitful asso-

ciation—and their friendship—ended in 1941. Houseman

went on to work briefly for

DAVID O

.

SELZNICK

Productions

before quitting to join the war effort in radio communica-

tions in early December 1941.

When he returned to Hollywood, Houseman coscripted

one film, Jane Eyre (1944), which, ironically, starred Welles.

He then went on to produce such hits as The Blue Dahlia

(1946), Max Ophuls’s classic Letter from an Unknown Woman

(1948), the first film by his young protégé,

NICHOLAS RAY

,

They Live by Night (1949), then Ray’s On Dangerous Ground

(1952),

VINCENTE MINNELLI

’s The Bad and the Beautiful

(1952), Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Shakespearean all-star Julius

Caesar (1953), and two more Minnelli winners, Lust for Life

(1956) and Two Weeks in Another Town (1962).

In the mid-1960s, Houseman took his first real acting

role in Seven Days in May (1964). But it was for his second

film appearance, as the autocratic, tyrannical Professor

Kingsfield in The Paper Chase (1973), that he received a great

deal of attention, stealing the movie and winning an Academy

Award for Best Supporting Actor as well. He went on to

recreate the role in a TV series of the same name.

Houseman later appeared in many TV movies as well as

in such theatrical films as Rollerball (1975), Three Days of the

Condor (1975), St. Ives (1976), The Cheap Detective (1978), My

Bodyguard (1980), The Fog (1980), Bells (1980), Ghost Story

(1981), and others. In the years before his death, he became

best known to the mass audience as a TV pitchman for sev-

eral different products.

Howard, Leslie (1893–1943) He was among the most

charming of English actors ever to grace a Hollywood sound-

stage. With his long, thin face, sensitive eyes, high forehead,

and delightfully musical speaking voice, Howard was an upper-

crust hero who was at his best playing clever but kindly intel-

lectuals and idealistic dreamers. Though English by birth and

beloved in his home country, most of his movies were either

made or financed by Hollywood studios. As far as American

audiences were concerned, he was their Englishman.

Born Leslie Stainer in London to Hungarian parents,

Howard was a first-generation Englishman who fought for

his country in World War I, only to be sent home in 1917

suffering from shell shock. It was his mother’s idea that he

become involved in the theater to get his mind off his trou-

bles. He learned his trade on the stage during the next five

years before becoming a Broadway notable in 1922, when he

made his New York debut in Just Suppose.

He was a major star of the stage throughout the rest of

the 1920s, and it led to the filming of one of his stage hits

Outward Bound, for

WARNER BROS

. in 1930. The bizarre film

about people on an ocean liner who eventually discover that

they are all dead was a surprise hit, and Howard became a hot

property in Hollywood.

He starred in films for MGM, RKO, and Paramount dur-

ing the next two years, the best of his films being Service for

Ladies (1932). He had been considered for the part of Dr.

Henry Frankenstein in the 1931 film Frankenstein, but the

role went to Colin Clive, instead, and perhaps both actors

were best served by that decision.

Howard also nixed the role of Garbo’s lover in Queen

Christina (1933) because he thought, and rightly so, that he’d

be overshadowed by the actress. But he scored a hit in Berke-

ley Square that same year and signed a nine-film contract with

Warner Bros. that led to his starring with

BETTE DAVIS

in the

critical success Of Human Bondage (1934). Warner then

loaned him to Alexander Korda in England for what became

one of Howard’s biggest triumphs of the 1930s, The Scarlet

Pimpernel (1935).

Howard, meanwhile, had starred on Broadway in Petrified

Forest. When Warner Bros. bought the rights to the play with

the intention of having Howard star as the dreamy idealist

hero, the actor balked unless his costar in the play,

HUMPHREY BOGART

, was allowed to play Duke Mantee in

the film version. The studio eventually agreed, and Bogart’s

film career was established.

A picture that Howard should have refused at all costs,

however, was Romeo and Juliet (1936). He was too old to play

Romeo, but he spoke the lines beautifully, nonetheless, and

the critics were kind.

In the latter 1930s, Howard found his way into a couple

of delightful light comedies, It’s Love I’m After (1937) and

Stand-In (1937), but his three best-remembered roles from

the end of the decade were in Pygmalion (1938), Intermezzo

(1939), and

GONE WITH THE WIND

(1939).

Howard starred in and codirected Pygmalion with Gabriel

Pascal in England, and his performance as Professor Henry

Higgins is a gem. He was offered Intermezzo by Selznick if

only the actor would play Ashley Wilkes in Gone With the

Wind, a role that Howard detested. The actor agreed, and

Howard’s portrayal of Ashley is the one by which most casual

movie fans remember him today.

When war broke out in Europe, Howard returned to

England to star, direct, and produce rousing pro-

HOWARD, LESLIE

206

English/anti-Nazi films that cheered his countrymen, the

most memorable of them being Pimpernel Smith (1941) and

Spitfire (1942). As a symbol of England’s steadfast courage,

Howard was sent to Spain and Portugal by his government

on a secret mission to help keep those two countries from

joining forces with the Axis powers. On his return trip, his

plane was shot down by Nazi fighters who thought they were

attacking Winston Churchill’s plane returning from Algiers

that same day. Leslie Howard was killed, and his loss was

mourned by millions on both sides of the Atlantic.

Howard, Ron (1954– ) Originally a child actor in

movies (and later on TV) known as Ronny Howard, he

developed into one of Hollywood’s most successful directors.

With a commercial touch leavened with a surprising sensitiv-

ity, he fashioned an enviable record of critical and box-office

hits during the 1980s.

Howard began to act at two years of age when he

appeared on stage with his parents in a Baltimore produc-

tion of The Seven Year Itch. The first of his handful of early

film appearances was in The Journey (1959). He was more

noticeable in The Music Man (1962) and finally the very cen-

ter of attention in The Courtship of Eddie’s Father (1963). He

was best known, however, as Opie on TV’s long-running

Andy Griffith Show and later as Richie on Happy Days. His

Richie was a reprise, of sorts, of the ordinary high school

senior he played in

GEORGE LUCAS

’s hit film

AMERICAN

GRAFFITI

(1973).

The actor didn’t fare very well as Ron Howard, a name he

preferred after becoming an adult. Typed by his success in

Happy Days, he had few roles of note until he played the

young man who learned a few lessons about life from

JOHN

WAYNE

in The Shootist (1976) and then starred in a low-

budget but fast-paced racing movie, Eat My Dust! (1976). His

success in the latter film gave him the opportunity to cowrite,

direct, and star in a similar film, Grand Theft Auto (1977),

which turned a profit at the box office and received some

admiring nods from the critics for its competence and energy.

During the 1980s, Howard emerged from low-budget

crash-and-cash films with Night Shift (1982), the sleeper

comedy hit of the year, which he followed with yet another

comedy hit surprise, Splash (1984). Howard then made the

ambitious science-fiction drama Cocoon (1985) and won uni-

versal praise for his sensitive direction of one of the year’s

biggest box-office winners. It appeared as if he could do no

wrong until he directed Gung Ho (1986), a badly calculated

flop. Yet producer and writer

GEORGE LUCAS

had plenty of

faith in Howard and invited him to direct Willow (1988), a

big budget fantasy film that was a box-office disappointment.

He rebounded smartly, however, with his direction of Par-

enthood (1989).

Howard had another hit with Backdraft, a firefighting film

with spectacular visual effects. Far and Away (1992) and The

Paper (1994) were commercially successful, but the astronaut

film Apollo 13 (1995) was his best 1990s work, both commer-

cially and critically. Howard won the Best Director Award

from the Directors Guild for the film. During the next five

years he was primarily a producer, though a film was made

about his directing talents in 1997.

Howard’s directing efforts were richly rewarded when he

received an Oscar as best director for A Beautiful Mind

(2001), starring

RUSSELL CROWE

. After considering a project

concerning the Alamo, Howard directed a supernatural west-

ern, The Missing (2003), starring Cate Blanchett and

TOMMY

LEE JONES

.

Howe, James Wong (1899–1976) One of the giants

of cinematography, his career in Hollywood spanned 50

years. Howe’s black-and-white photography, in particular,

was always sensitive and ingenious. He worked for virtually

all of the major studios, but in the late 1930s and 1940s, he

did some of his best work for

WARNER BROS

., or so it seemed

until his artistry was put on full view in his two Oscar-win-

ning films, The Rose Tattoo (1955) and Hud (1963).

Howe’s original name was Wong Tung Jim. Drawn to the

fledgling movie business, he began to work in Hollywood in

1917 as an assistant cameraman to

CECIL B

.

DEMILLE

, even-

tually becoming a second cameraman. His promotion to

director of photography in 1923 was the result of a fluke.

Howe had taken some still photographs of one of

DeMille’s great stars, Mary Miles Minter. She loved the pic-

tures and insisted that he become her cameraman on all her

HOWE, JAMES WONG

207

Ron Howard on the set of A Beautiful Mind (2002)

(PHOTO COURTESY UNIVERSAL STUDIOS)