Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

decade the WCTU became increasingly

politically active by forging an alliance

with the Prohibition Party and endorsing

presidential candidates. In addition,

Willard successfully lobbied the Prohibi-

tion Party to include a suffrage plank in its

1888 platform. She led the WCTU in ex-

panding its social reform programs to en-

compass establishing free kindergartens,

reducing the workday to eight hours,

passing protective labor legislation, rais-

ing the legal age of consent for sex, tough-

ening rape laws, and closing businesses on

Sunday.

See also Suffrage; Temperance

Movement, Women in the; Woman’s

Christian Temperance Union

References Lee, “Do Everything” Reform:

The Oratory of Frances E. Willard (1992).

Willebrandt, Mabel Walker (1889–1963)

The first female public defender in the United States, Mabel Walker Wille-

brandt became an assistant attorney general in 1921, making her the first

woman to hold a permanent subcabinet-level appointment. Seven years

later, in 1928, she chaired the Credentials Committee of the 1928 Repub-

lican National Convention and with that appointment became the first

woman to chair an important national convention committee for either

party. Throughout her career, she worked to advance the opportunities

and careers of other women lawyers.

Born in a sod dugout in southwestern Kansas, Willebrandt attended

Park College and Academy in Kansas from 1906 to 1907. She married in

1910 and moved to Arizona because of her husband’s poor health. She

earned her teaching certificate from Arizona’s Tempe Normal School in

1911, and the couple moved to the Los Angeles area, where she taught

school during the day and attended law school at night, earning her bach-

elor of laws degree from the University of Southern California in 1916 and

her master of laws degree from the same school the next year. She began

her law career as the assistant public defender in Los Angeles, working on

more than 2,000 cases brought against women, particularly charges for

prostitution. By 1918, she had established herself within the legal profes-

sion in Los Angeles, helped organize the Women’s Law Club of Los Ange-

les County, and developed an active private practice.

Willebrandt, Mabel Walker 699

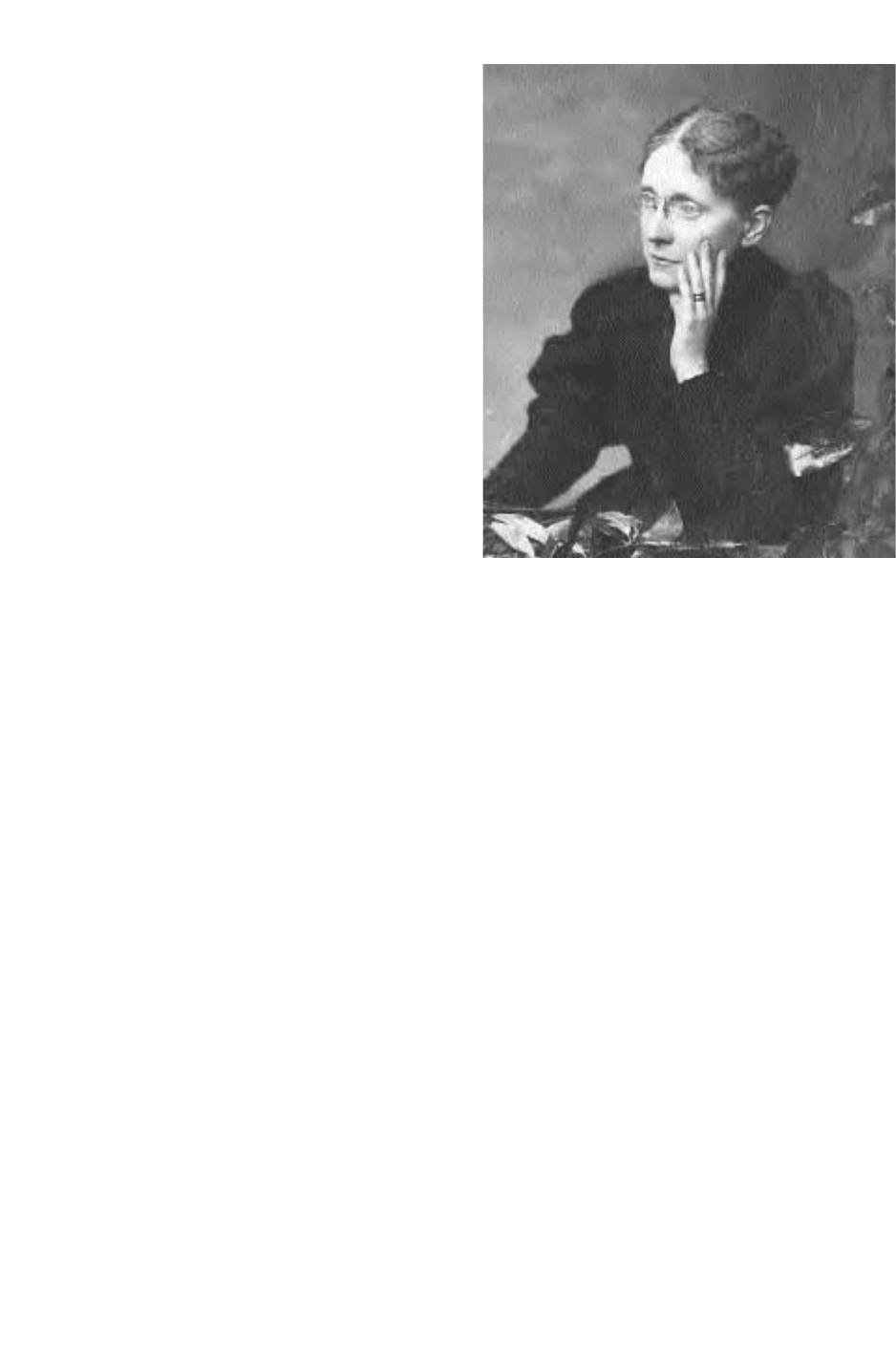

Frances Willard,

president of the

Woman’s Christian

Temperance Union

and suffragist leader,

between 1880 and

1898 (Library of

Congress)

Willebrandt began her political career by campaigning for candidates

and became a member of the California Republican State Central Commit-

tee which, combined with her legal skills, led to her appointment in 1921 as

a U.S. assistant attorney general by President Warren G. Harding. In charge

of Prohibition enforcement, taxes, and the Bureau of Federal Prisons, her

responsibilities included coordinating the enforcement programs of the

Treasury Department, the Coast Guard, and state and local law enforcement

agencies. Willebrandt became most widely known for her prosecution of

Prohibition cases, leading New York governor Alfred E. Smith to refer to her

as “Prohibition Portia.” She responded:“It is not particularly gratifying to be

thought of merely as a Nemesis of bootleggers, a chaser of criminals.” Her

first big cases came in 1922, when she broke two southern rings, one in Sa-

vannah, Georgia, and the other in Mobile, Alabama, in which Congressman

John W. Langley of Kentucky was found guilty. Willebrandt developed a

novel strategy for enforcing the Volstead Act when she decided to use in-

come tax evasion as a way to stop bootleggers. She preferred enforcing tax

laws because, as she said: “They require detached and abstract thought, an

intellectual exercise of which women were once thought incapable.”

Willebrandt aggressively pursued those who broke the law, filing be-

tween 49,000 and 55,000 criminal and civil cases annually. In these cases,

she helped establish the constitutional validity of the Volstead Act and

other laws through U.S. Supreme Court decisions. Of the thirty-nine cases

she argued before the Court, she won thirty-seven. By 1929, of all the

lawyers who had argued cases before the Court, she ranked fourth in the

total number of cases she had presented.

With prisons filling with Volstead violators, the need for additional

space in them grew, as did the need to review the related policies. Wille-

brandt began by calling for a federal women’s prison, for which she sought

support from the Women’s Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC).

With the WJCC’s help, she found support from the League of Women

Voters, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the General Federa-

tion of Women’s Clubs (GFWC), and several other groups. She also be-

lieved that young, male, first-time offenders serving their sentences in

prison were further corrupted by the exposure to more experienced law

violators and that a federal reformatory for them was needed. By enlisting

the support of the Young Men’s Christian Association, GFWC, American

Bar Association, Kiwanis Club International, and other groups, Wille-

brandt succeeded in creating a federal reformatory. In addition, she

sought to improve prison conditions and to provide work within prisons.

Her first task, however, was to identify and remove corrupt and incompe-

tent prison officials by planting government agents posing as inmates

within the facilities. With the support of GFWC and others interested in

700 Willebrandt, Mabel Walker

prison reform, she then began developing prison industries to provide

employment for every prison inmate, engaging in perennial battles for ap-

propriations for the programs.

In 1928, Willebrandt turned some of her attention to the Republican

Party and to making Herbert Hoover the party’s presidential nominee.

She attended the Republican National Convention as a Hoover delegate

and was permanent chair of the party’s Credentials Committee. As Cre-

dentials Committee chair, Willebrandt worked to ensure that the com-

mittee decided in favor of delegates pledged to Hoover, which helped him

obtain the nomination. A dedicated Hoover supporter, Willebrandt

worked for him throughout the campaign and became the center of a na-

tional controversy. In a speech to a group of Methodists who supported

Prohibition, Willebrandt questioned Democratic presidential nominee Al

Smith’s commitment to enforcing the Volstead Act and characterized

Hoover as ready to provide the necessary leadership in enforcing it. In that

and subsequent speeches to other religious groups, she referred to Smith’s

religion, Catholicism, making it an issue in the campaign. Willebrandt was

attacked by the press for injecting religion into the presidential race, and

some Republican leaders wanted her silenced. One leading feminist, how-

ever, viewed the dispute as testimony that a woman had enough political

power to be the center of a disagreement. Commenting on the criticism

heaped on Willebrandt, Democratic Party leader Emily Newell Blair said

that Willebrandt was the first woman to make a place for herself as a “great

figure in politics.” After Hoover won the election, Willebrandt concluded

that he was not as committed to enforcing Prohibition as she had thought

and resigned as assistant attorney general in May 1929.

Willebrandt joined Aviation Corporation as general counsel and be-

gan a new career in the emerging field of aviation law, chairing a commit-

tee on the topic for the American Bar Association from 1938 to 1942. She

also pioneered in the area of radio law, winning a U.S. Supreme Court de-

cision that upheld the Federal Radio Commission’s power to regulate

broadcasting. In addition, she worked for Louis B. Meyer of MGM Studio

and Hollywood stars and other celebrities.

See also General Federation of Women’s Clubs; Langley, Katherine Gudger;

League of Women Voters; Woman’s Christian Temperance Union; Women’s

Joint Congressional Committee

References Brown, Mabel Walker Willebrandt (1984); New York Times, 9 April

1963; Strakosh, “A Woman in Law” (1927).

Williams v. Zbaraz (1980)

Decided with Harris v. McRae, Williams v. Zbaraz challenged an Illinois

statute prohibiting state medical assistance payments for all abortions

Williams v. Zbaraz 701

except those to save the life of the woman seeking the abortion. Approach-

ing this case as a class action suit, the challengers argued that even though

Medicaid funding for medically necessary abortions had ended with the

passage of the Hyde Amendment, the state still had an obligation to pay for

them under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the argument, saying that a state

was not obligated to pay for medically necessary abortions that were not

covered by Medicaid and that the policy did not violate the equal protec-

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

See also Abortion; Harris v. McRae

References Williams v. Zbaraz, 448 U.S. 358 (1980).

Wilson, Edith Bolling Galt (1872–1961)

First lady from 1915 to 1921, Edith Wilson was the wife of President

Woodrow Wilson. After President Wilson suffered a stroke in October

1919, Edith Wilson controlled who could see her husband during the six

months of his convalescence, and every document that the president re-

ceived went first to his wife. Edith Wilson did not attempt to run the pres-

idency, but her control over access to the president determined which

matters received his attention and which would languish. Edith Wilson

kept the president’s condition a secret from all except his doctor and a few

intimates; she did not inform the cabinet.

Born in Wytheville, Virginia, Edith Wilson learned to read and write

at home and attended Martha Washington College, a girls’ preparatory

school, from 1887 to 1888 and Powell’s School from 1889 to 1890. Her

first husband, Norman Galt, died in 1908. Edith Wilson was Woodrow

Wilson’s second wife; his first wife, Ellen, had died in 1914. Edith Wilson

and Woodrow Wilson met at the White House when she was there for tea,

and after a brief courtship, they married.

References Weaver, “Edith Bolling Wilson as First Lady: A Study in the Power of

Personality, 1919–1920” (1985).

Wilson, Heather (b. 1960)

Republican Heather Wilson of New Mexico was elected to the U.S. House

of Representatives on 23 June 1998. Wilson won her seat in a special elec-

tion to fill the vacancy created by the death of the incumbent. She is the

first woman veteran ever elected to Congress.

Born in Keene, New Hampshire, Wilson earned her bachelor of sci-

ence degree from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1982. She earned her

master’s of philosophy in 1984 and her doctor’s degree in philosophy in

1985, both from Oxford University. Wilson served as an Air Force officer

702 Wilson, Edith Bolling Galt

until 1989, when she became director for European defense policy and

arms control on the National Security Council staff. In 1991 she founded

a business consulting firm that worked with senior executives in U.S. de-

fense and scientific corporations. She served as cabinet secretary of the

New Mexico Children, Youth, and Families Department, leading the de-

velopment of programs that addressed juvenile crime, abuse and neglect,

and child care and early education.

After winning the special election in June 1998, Wilson won reelec-

tion to her seat in the November general elections of that year. Her con-

gressional priorities include improving teacher training, strengthening

curricula and early childhood education, eliminating the marriage penalty

in income taxes, and maintaining the solvency of Social Security. She cast

her vote in Congress for a bill to reform the Internal Revenue Service.

See also Congress, Women in

References “Heather Wilson, R-N.M. (1)” (1998); www.house.gov/wilson/

biography/index.htm.

Wingo, Effiegene Locke (1883–1962)

Democrat Effiegene Wingo of Arkansas served in the U.S. House of Rep-

resentatives from 4 November 1930 to 3 March 1933. After the death of

her husband, Representative Otis Wingo, Effiegene Wingo was elected to

fill the vacancy and then to a full term. She worked to establish a game

refuge in Ouachita National Forest, to create Ouachita National Park, and

to complete construction of a railroad bridge in her district. Her district

had suffered from natural disasters and from the effects of the Depression,

problems she attempted to address by seeking various relief measures. She

retired from office after serving the full term and in 1934 was a cofounder

of the National Institute of Public Affairs, which provided internships in

Washington to students.

Born in Lockesburg, Arkansas, Wingo studied music at the Union Fe-

male Seminary and graduated from Maddox Seminary in 1901.

See also Congress, Women in

References Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives, Women in

Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

WISH List

Founded in 1992, the WISH List supports prochoice Republican women

for elective offices at every level. The WISH List is an acronym for

Women in the Senate and House. In its first seven years, the WISH List

raised $1.5 million and supported the successful candidacies of New Jer-

sey governor Christine Todd Whitman; U.S. senators Susan Collins, Kay

WISH List 703

Bailey Hutchison, and Olympia Snowe; and ten women members of the

U.S. House of Representatives.

The WISH List process for assisting candidates begins with identify-

ing a Republican prochoice woman candidate and investigating her or-

ganization, the race, and her likelihood of winning. After selecting candi-

dates, the WISH List recommends them to its members, including a profile

of the candidate and her positions on key issues. WISH List members se-

lect at least two of the endorsed candidates and send their contributions to

WISH List, which bundles them and forwards them to the candidates.

See also Abortion; Collins, Susan Margaret, Hutchison, Kathryn (Kay) Ann

Bailey; Republican Party, Women in the; Snowe, Olympia Jean Bouchles;

Whitman, Christine Todd

References www.thewishlist.org.

Wollstonecraft, Mary (1759–1797)

Englishwoman Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights

of Woman in 1792, a challenge to contemporary philosophers’ views of

women and their intellectual abilities. She conceded that many women

were vain, ignorant, and childish but argued that women were denied the

education and opportunity to develop their skills. She advocated educa-

tion, opportunities to develop physical strength, and equal rights for

women. Her book provided some of the philosophical basis for the suf-

frage movement that developed in the United States in the nineteenth

century. Lucretia Mott, a leader of that movement, called it her “pet book,”

and when suffragists published their history of the movement, Woll-

stonecraft was among the women to whom they dedicated it.

Born near London, Mary Wollstonecraft rejected becoming depen-

dent upon anyone else when she was fifteen years old. Self-educated, she

opened a school and ran it for several years. After the school began to lose

money and closed, Wollstonecraft began a career as a writer.

See also Suffrage

References Gurko, Ladies of Seneca Falls: The Birth of the Woman’s Rights Move-

ment (1974); Matthews, Women’s Struggle for Equality (1997).

Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

Founded in 1874, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)

sought to obtain pledges of total abstinence from alcohol and later added

tobacco and other drugs. When Frances Willard became WCTU president

in 1879, she added a political dimension to the moral suasion used to

achieve the goal of abstinence. Using the motto “do everything,” the or-

ganization expanded its areas of interest to include establishing and man-

704 Wollstonecraft, Mary

aging day care centers, providing housing for homeless people, and setting

up medical clinics—any project that members believed would contribute

to achieving abstinence. WCTU advocated a range of social reforms, from

woman suffrage to equal pay for equal work to federal aid for education.

Willard’s presidency ended in 1898, and the WCTU narrowed its scope to

a stronger focus on temperance. After passage of the Eighteenth Amend-

ment in 1919, which started Prohibition, the WCTU returned to a broader

social reform agenda. For example, it worked with the Women’s Joint

Congressional Committee to establish a federal women’s prison in the

1920s. The oldest voluntary, nonsectarian women’s organization in con-

tinuous existence in the world, the WCTU continues to advocate absti-

nence from alcohol and tobacco and has added marijuana and other

drugs to its agenda.

See also Suffrage; Temperance Movement, Women in the; Willard, Frances

Elizabeth Caroline; Willebrandt, Mabel Walker

References www.wctu.org.

Woman’s National Loyal League

Organized in 1863 by women’s rights leaders and abolitionists Elizabeth

Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the Woman’s National Loyal League

supported the constitutional amendment banning slavery in the United

States. At the founding convention, attendees adopted resolutions sup-

porting the government as long as it pursued freedom for slaves and

pledged to collect 1 million signatures calling for passage of the Thir-

teenth Amendment. Stanton served as the organization’s president and

Anthony as its secretary.

Two thousand women, men, and children circulated the petitions,

with Stanton offering honor badges to the children who collected 100

names. The league gathered 100,000 names, presenting them to the U.S.

Senate on 9 February 1864. When the league disbanded in August 1864, it

had collected 400,000 signatures. The Thirteenth Amendment passed

Congress in early 1865 and was ratified by the states that year.

See also Abolitionist Movement, Women in the; Anthony, Susan Brownell;

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady

References Flexner and Fitzpatrick, Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights

Movement in the United States, enlarged edition (1996).

Woman’s Peace Party

Founded in 1915 in response to World War I, the Woman’s Peace Party

(WPP) included delegates from the Daughters of the American Revolu-

tion, the Congressional Union, the Woman’s Christian Temperance

Woman’s Peace Party 705

Union, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Women’s Trade

Union League, and several other women’s organizations. At the organiza-

tional meeting, the WPP passed planks calling for arms limitations, medi-

ation of the European conflict, the establishment of international laws to

prevent war, woman suffrage, and other measures. By 1916, the WPP had

40,000 members, the highest membership it would ever have. In addition

to World War I, the WPP protested the presence of U.S. troops in Haiti

and the Dominican Republic, U.S. bases in Nicaragua, and the colonial

government in Puerto Rico.

As the United States prepared to enter the war, divisions developed

within the WPP as leaders and members questioned their responsibilities

to their government and as Congress passed measures related to loyalty

and treason. Membership declined in some parts of the country, but some

WPP members remained steadfast in their advocacy for peace. In 1919,

the WPP became the U.S. branch of the Women’s International League for

Peace and Freedom.

See also Congressional Union; General Federation of Women’s Clubs; Woman’s

Christian Temperance Union; Women’s International League for Peace and

Freedom; Women’s Trade Union League

References Alonso, Peace as a Women’s Issue: A History of the U.S. Movement for

World Peace and Women’s Rights (1993).

Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional

Occupations Act of 1992

Introduced by Republican congresswoman Constance A. Morella of

Maryland and passed by Congress in 1992, the Women in Apprenticeship

and Nontraditional Occupations Act offers grants to community-based

organizations to help businesses provide women with apprenticeships in

nontraditional occupations. Administered through the Department of La-

bor, the grants are also used to assist unions and employers in preparing

workplaces for women employees. The act seeks to prepare low-income

women and welfare recipients for jobs in the skilled trades and technical

positions, according to Republican senator Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas.

See also Kassebaum Baker, Nancy Landon; Morella, Constance Albanese

References Congressional Quarterly Almanac, 102nd Congress, 2nd Session...

1992 (1993).

Women Strike for Peace

Founded in 1961 to protest atmospheric tests and the danger of radioac-

tive pollution to children’s health, Women Strike for Peace (WSP) works

for the total elimination of nuclear weapons. As a radioactive cloud from

706 Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations Act of 1992

a Russian nuclear test hung over the United States, 50,000 women in more

than sixty cities went on strike on 1 November 1961, in the largest

women’s peace action in the nation to that date. Women lobbied Congress

and government offices to “End the Arms Race—Not the Human Race.”

During the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, more than 20,000 women across the

country marched in protest. In 1963, WSP helped convince President John

F. Kennedy to complete the limited nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet

Union.

WSP began in book illustrator Dagmar Wilson’s home, where she had

gathered five women to discuss the nuclear crisis. Through their networks

with members of the Women’s International League for Peace and Free-

dom, the League of Women Voters, and other peace activists, they distrib-

uted a call for the November 1961 strike. A grassroots movement, WSP has

no formal organization, president, board of directors, formal membership,

or official policies. Local groups may or may not work together.

In 1962 the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) sub-

poenaed Wilson and several WSP members as part of its investigation of

peace groups and Communist involvement in them. Instead of being fear-

ful of the committee and its interrogation, Wilson and her colleagues be-

littled the committee with humor and their moral superiority. They ac-

knowledged that Communists could be members but explained they did

not know of any. Invoking the Fifth Amendment dozens of times, they

also lectured the committee members as they attempted to explain WSP’s

lack of traditional organization. WSP members received favorable press,

and the press ridiculed HUAC, which admitted that WSP was not a sub-

versive organization.

In other areas, WSP has pressured toy manufacturers to stop pro-

ducing toy guns and war toys and has asked retailers to stop selling them.

It issued a Children’s Bill of Rights, which called for food, shelter, medical

care, and education for all children.

See also League of Women Voters; Women’s International League for Peace

and Freedom

References Linden-Ward and Green, American Women in the 1960s: Changing

the Future (1993).

Women Work! The National Network for Women’s Employment

Women Work! was founded in 1974 to provide advocacy for and assis-

tance to women whose marriage had ended and with it their economic

support. Two California women, divorcée Tish Sommers and widow Lau-

rie Shields, created the organization, originally known as the Alliance for

Displaced Homemakers and later as the National Displaced Homemakers

Network. The organization gained its current name in 1993.

Women Work! The National Network for Women’s Employment 707

Displaced homemakers are women whose marriage has ended, re-

gardless of the reason. Women Work! contends that for many women,

when their marriage is over, their employment also effectively ends, and

that those women need job training and other assistance to support them-

selves. The Displaced Homemakers Self-Sufficiency Assistance Act of 1990

was passed with the support of Women Work!

See also Displaced Homemakers

Women’s Bureau

Created in 1920, the Women’s Bureau is the single federal government unit

exclusively concerned with serving and promoting the interests of work-

ing women. The Women’s Bureau’s mandate states: “It shall be the duty of

said bureau to formulate standards and policies which shall promote the

welfare of wage-earning women, improve their working conditions, in-

crease their efficiency, and advance their opportunities for profitable em-

ployment.” The Women’s Bureau fulfills its mission by alerting women to

their rights in the workplace, proposing legislation that benefits working

women, researching and analyzing information about women and work,

and reporting its findings to the president, Congress, and the public.

The Women’s Bureau began first as the Women’s Division of the

Ordnance Department during World War I. As increasing numbers of

women filled jobs previously held by men who had been called to war, the

division was established to monitor the needs of women entering the mu-

nitions industry. In 1918, the division was moved to the Labor Depart-

ment and renamed Women in Industry Service.

When World War I ended and concerns arose that Women in Indus-

try Service would be disbanded and the needs of women workers would

be ignored, the New York Women’s Trade Union League began lobbying

for a permanent government agency. The result was the creation of the

Women’s Bureau in 1920 as part of the Department of Labor. The first di-

rector, Mary Anderson, who served from 1920 to 1944, was an organizer

for the Women’s Trade Union League.

The relationship between the Women’s Trade Union League and the

Women’s Bureau involved mutual support and a shared agenda. Both groups

strongly supported protective legislation for women, including limits on the

hours women could work, the amount of weight they could lift, and other

matters. A consequence of the Women’s Bureau’s commitment to protective

legislation was its opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), pro-

posed in 1923 by Alice Paul of the National Woman’s Party. The bureau re-

mained opposed to the amendment until 1969, when under the leadership

of Director Elizabeth Duncan Koontz, it came to support the ERA.

708 Women’s Bureau