Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chavez, Vietnam War resister David Miller,

Vietnam War opponents Reverends Daniel

Berrigan and Philip Berrigan, and others

found inspiration in her message and

courage from her example.

Day wrote From Union Square to

Rome (1938), House of Hospitality (1939),

On Pilgrimage (1948), Therese (1960),

Loaves and Fishes (1963), and On Pilgrim-

age: The Sixties (1972). Day spent the last

days of her life at one of the hospitality

houses she had founded.

References Forest, Love Is the Measure

(1986); New York Times, 8 November

1972, 30 November 1980.

Declaration of Sentiments and

Resolutions (1848)

See Seneca Falls Convention

Decter, Midge Rosenthal (b. 1927)

Conservative social critic and writer Midge Decter has condemned mod-

ern feminists, arguing that they do not seek freedom from sexual discrim-

ination, but freedom from responsibility. She contends that feminists fear

the many options available to them and want to retreat into self-absorp-

tion. She believes that modern birth control methods, not the feminist

movement, opened career opportunities to women. She criticized parents

in the 1970s for tolerating their children’s rebellion against society and

called on parents to accept their responsibility “to make ourselves the fi-

nal authority on good and bad, right and wrong.”

Decter’s career includes editorial positions on several magazines,

among them managing editor of Commentary from 1961 to 1962, executive

editor of Harper’s Magazine from 1969 to 1971, and book review editor of

Saturday Review/World magazine from 1972 to 1974. Her books include The

Liberated Woman and Other Americans (1971), The New Chastity (1972), and

Liberal Parents, Radical Children (1975). A founder of the Committee for the

Free World, she was the organization’s executive director from 1980 to 1990.

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, Decter attended the University of Min-

nesota from 1945 to 1946 and Jewish Theological Seminary from 1946 to

1948.

References H. W. Wilson, Current Biography Yearbook, 1982 (1982).

Decter, Midge Rosenthal 185

Dorothy Day, radical

Socialist and publisher

of the Catholic

Wor ker, strived in

New York’s poorest

neighborhoods to feed

the hungry and shelter

the homeless, ca. 1943

(Library of Congress)

Deer, Ada Elizabeth (b. 1935)

Native American Ada Deer became the

first woman to head the Bureau of Indian

Affairs (BIA) in 1993, serving until 1997.

During her confirmation hearings, she

told the Senate Committee on Indian Af-

fairs: “Personally, you should know that

forty years ago, my tribe, the Menominee,

was terminated; twenty years ago we were

restored; and today I come before you as a

true survivor of Indian policy.” As head of

the BIA, Deer administered a budget of

$2.4 billion and managed more than

12,000 employees, the largest agency in

the Department of Interior. Deer sought

to create a federal-tribal partnership to

fulfill promises made by the government

and to address injustices. She believed that

the federal government’s role was to support tribal sovereignty and to im-

plement solutions developed by tribes for problems identified by tribes.

During her tenure, more than 220 Alaska Native villages received recogni-

tion, and the number of self-governance tribes increased, as did the num-

ber of tribes contracting for services previously administered by the fed-

eral government. In addition, she reorganized the Bureau.

The cause that drew Deer into politics was the restoration of the

Menominee tribe. A 1953 law had terminated the Menominee Reserva-

tion, and by 1961, federal control over tribal affairs had ended. Without

federal involvement, health and education benefits ended, and the owner-

ship of tribal lands was threatened. In the early 1970s, Deer and other

leaders formed the Determination of the Rights and Unity for Menomi-

nee Shareholders (DRUMS), with the goal of restoring the tribe’s recogni-

tion. As lobbyist for the group, Deer won passage of an act to restore fed-

eral recognition of the Menominees, making them eligible for federal

services. Elected chair of the Menominee Restoration Committee in 1974,

Deer led the tribe through the process of reestablishing itself; created an

administrative structure; oversaw its financial, judicial, and legislative af-

fairs; and helped write its constitution.

Born in Keshena, Wisconsin, on the Menominee Indian Reservation,

Ada Deer lived in a one-room log cabin the first twelve years of her life.

The daughter of a white mother and Menominee Indian father, she earned

her bachelor’s degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin in

1957 and a master’s degree from the Columbia School of Social Work in

186 Deer, Ada Elizabeth

Ada Deer, the first

Native American

woman to administer

the U.S. Bureau of

Indian Affairs

(Courtesy: Bureau

of Indian Affairs)

1961. She studied law at the University of Wisconsin and the University of

New Mexico and was a fellow at the Harvard Institute of Politics, JFK

School of Government, in 1977.

References H. W. Wilson, Current Biography Yearbook, 1994 (1994);

www.doi.gov/adabio.html.

DeGette, Diana (b. 1957)

Democrat Diana DeGette of Colorado entered the U.S. House of Repre-

sentatives on 3 January 1997. DeGette held the leadership position of

House deputy minority whip in the 106th Congress (1999–2001). She has

focused on expanding health care for children, regulating smoking and to-

bacco, and protecting the environment. DeGette has worked to expedite

the restoration of polluted areas, particularly the Rocky Mountain Arse-

nal, a Superfund site. During her first term in office, she passed a measure

to increase the number of children enrolled in Medicaid.

DeGette served in the Colorado House of Representatives from 1993

to 1997, where she was instrumental in passing a bill ensuring women un-

obstructed access to abortion clinics and other medical care facilities. She

passed the state’s Voluntary Cleanup and Redevelopment Act, considered

a model for environmental cleanup programs.

Born in Tachikawa, Japan, Diana DeGette earned her bachelor’s de-

gree from Colorado College in 1979 and her law degree from New York

University Law School in 1982. She practiced law in Denver, focusing on

civil rights and employment litigation, for fifteen years.

See also Congress, Women in; State Legislatures, Women in

References Congressional Quarterly, Politics in America 1998 (1997);

www.house.gov/degette/BIOLAST.htm.

DeLauro, Rosa L. (b. 1943)

Democrat Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut entered the U.S. House of Rep-

resentatives on 3 January 1991. DeLauro held the leadership position of

House chief deputy minority whip in the 104th and 105th Congresses

(1995–1999) and assistant to the Democratic leader in the 106th Congress

(1999–2001). A member of the House leadership, DeLauro led the fight to

increase federal funding for research on breast cancer and cervical cancer

and to enact a measure to ensure adequately long hospital stays for

women who have undergone breast cancer surgery. She has worked to re-

strict the development of new weapons systems and to help industries

make the transition from defense-related markets to commercial ones.

Before entering Congress, DeLauro was executive assistant to the

mayor of New Haven in 1976 and 1977 and was executive assistant to the

city’s development administrator from 1977 to 1979. Chief of staff for a

DeLauro, Rosa L. 187

U.S. senator from 1981 to 1987, she has also been executive director of

EMILY’s List.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Rosa L. DeLauro grew up in a po-

litical family, the daughter of an alderman and alderwoman. As a child,

she attended political gatherings with her parents. She studied at the Lon-

don School of Economics from 1962 to 1963, received a bachelor’s degree

from Marymount College in 1964, and earned a master’s degree from Co-

lumbia University in 1966.

See also Congress, Women in; EMILY’s List

References Boxer, Strangers in the Senate (1994); Congressional Quarterly,

Politics in America 1996 (1995); www.house.gov/delauro/bio.html.

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority

Founded in 1913 at Howard University, Delta Sigma Theta members have

pledged to take “concerted action in removing the handicaps under which

we as women and as members of a minority race labor.” With more than

190,000 members in more than 870 chapters in the United States and

eight other nations, Delta Sigma Theta is one of the largest African Amer-

ican women’s organizations in the world. Delta Sigma Theta has a five-

point agenda: economic development, educational development, interna-

tional awareness, physical and mental health, and political awareness and

involvement. Its legislative priorities include civil rights, voter registration

and education, health, education, child care, and employment.

Delta Sigma Theta challenged discrimination on college campuses,

188 Delta Sigma Theta Sorority

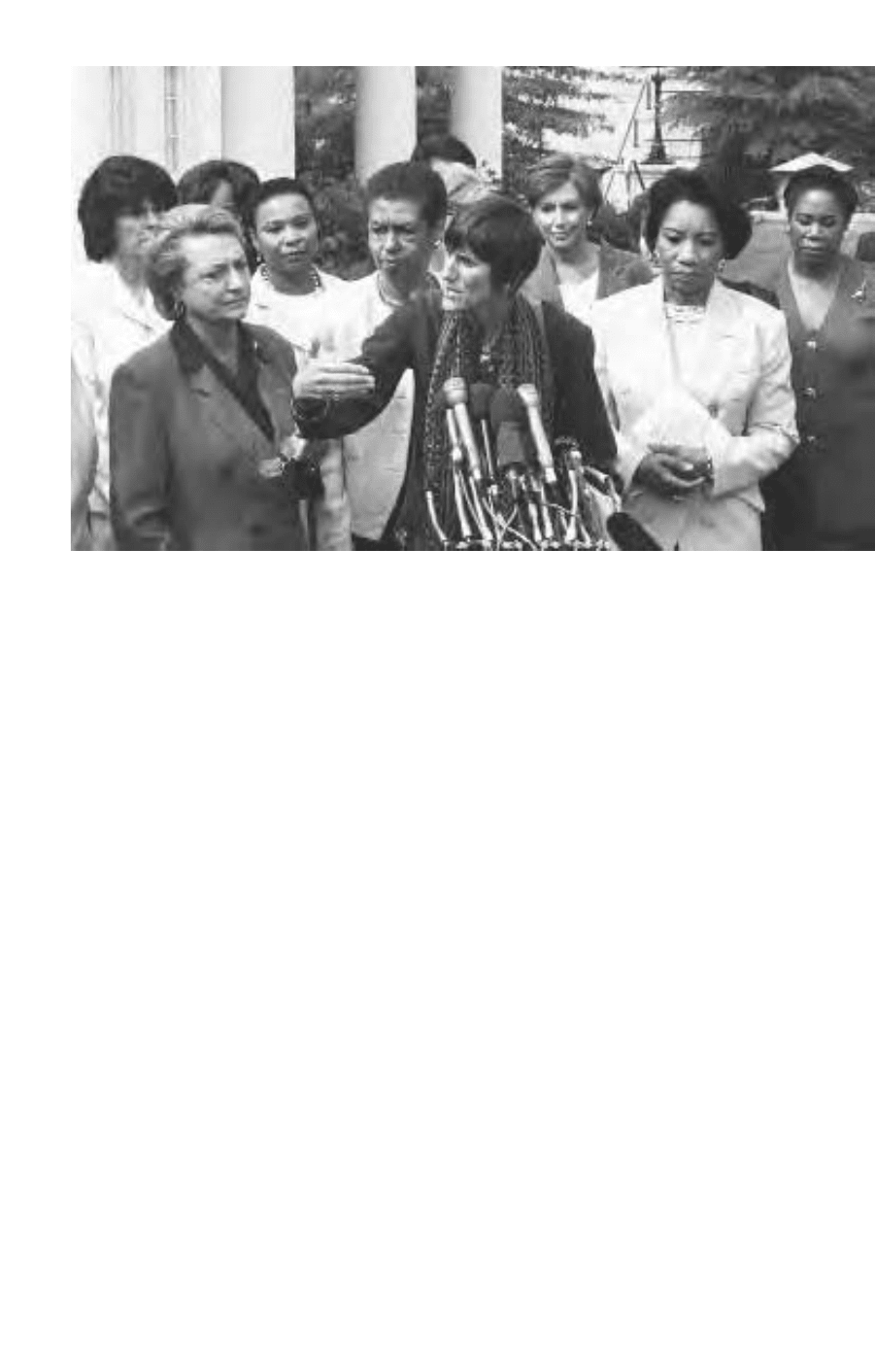

Representative Rosa

DeLauro (D-CT) led

a press conference

with Democratic

congresswomen (left

to right): Representa-

tive Lucille Roybal-

Allard (D-CA),

Representative

Barbara Kennelly

(D-CT), Delegate

Donna Christian-

Green (D-VI),

Delegate Eleanor

Holmes-Norton

(D-DC), Representa-

tive Nancy Pelosi

(D-CA), Representa-

tive Juanita Millen-

der-McDonald

(D-CA), and Repre-

sentative Cynthia

McKinney (D-GA),

1998 (Associated

Press AP)

sent a bookmobile to Georgia in the 1940s, and provided financial sup-

port for civil rights actions in the South during the 1960s. The organiza-

tion lobbied for a federal antilynching legislation, an end to discrimina-

tion in housing, and creation of a permanent Fair Employment Practices

Commission. It helped pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting

Rights Act.

Among those who have participated in Delta Sigma Theta’s leader-

ship training are former congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Barbara

Jordan as well as Patricia Harris, former secretary of both housing and ur-

ban development and health and human services.

See also Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority; Chisholm, Shirley Anita St. Hill; Civil

Rights Movement, Women in the; Evers-Williams, Myrlie Louise Beasley;

Harris, Patricia Roberts; Height, Dorothy Irene; Jordan, Barbara Charline; Suf-

frage; Terrell, Mary Eliza Church

References Giddings, In Search of Sisterhood (1988); Slavin, U.S. Women’s

Interest Groups (1995); www.dst1913.org.

Democratic Party, Women in the

The Democratic Party was the first of the two major parties to have a

woman chair its national committee and the only one of the two parties

to nominate a woman for vice president of the United States. After women

gained suffrage rights in 1920, women leaders in the party began a long

crusade to gain a share of the power and a voice in the decisionmaking

process. Several women have emerged as innovative and dynamic leaders

in the party and have created opportunities for other women in it.

The first woman went to a Democratic National Convention as a del-

egate in 1900, and the first woman served on a convention committee

(credentials) in 1916, the year the party created a Women’s Division.

Women’s formal entrance into the Democratic National Committee

(DNC), the party’s governing board, began in 1919, when the party cre-

ated the position of associate member. Associate members were appointed

by each state committee chair, one for each state, comparable to national

committeemen. Associate members had no vote but could voice their

opinions in DNC meetings. In 1920, the DNC created the voting position

of national committeewoman, replacing associate members. National

committeewomen, like national committeemen, had full voting rights,

were selected by their home state, and served for four-year terms.

Women’s roles, however, were limited. Men appreciated their work on the

party’s behalf but resisted giving them substantive roles or rewarding their

efforts with the appointments and other benefits granted to men.

One of the party’s earliest women leaders was Belle Moskowitz, who

was a publicist for Alfred Smith in his three campaigns for governor of

Democratic Party, Women in the 189

190

Democratic congresswomen celebrated at the Democratic National Convention (left to right): Representatives Nita

Lowey (D-NY), Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA), Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), Patricia Schroeder (D-CO), Barbara Kennelly

(D-CT), Lynn Woolsey (D-CA), and Maxine Waters (D-CA), 1996 (Associated Press AP)

New York in 1918, 1920, and 1922 and his presidential bid in 1928. Emily

Newell Blair was among the first group of national committeewomen, the

first female vice chair of the party in 1921, and the second chair of the

Women’s Division. As head of the Women’s Division, she helped organize

hundreds of Democratic women’s clubs, conducted training sessions, and

called on women to become active in the political party and to run for

public office.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, two women, Eleanor Roosevelt and

Molly Dewson, formed a political partnership that significantly changed

women’s roles and influence in the party. They shared a background in the

social reform movement, developed a deep and lasting friendship, and be-

came a powerful political force. Roosevelt recruited Dewson to Demo-

cratic Party politics, and the two women successfully organized women to

support Franklin Roosevelt’s gubernatorial campaigns in 1928 and 1930

and his 1932 presidential campaign. One of their innovations was known

as “rainbow fliers,” or campaign literature printed on colored paper and

used first in the gubernatorial campaigns. They sent millions of the fliers

to women during the presidential campaign, a strategy that men in the

party later adopted.

Following Franklin Roosevelt’s election to the presidency, Eleanor

Roosevelt and Dewson worked to enhance women’s roles in government

and in the party. After agreeing to head the Women’s Division of the party,

Dewson reportedly arrived in Washington, D.C., with a list of sixty women

for top government positions and worked to gain appointments for them.

Among her more notable achievements was Franklin Roosevelt’s choice for

secretary of labor, Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in a presiden-

tial cabinet. Dewson also won approval of a federal program for unem-

ployed women, a remarkable achievement during the Depression, when

women were being moved out of jobs to make them available for men.

In addition to expanding women’s roles within the Roosevelt admin-

istration, Dewson increased women’s effectiveness within the party by

training them and then utilizing their skills to benefit the party. For ex-

ample, Dewson trained women across the country to explain the benefits

of the New Deal to voters. With what some have called an avalanche of

colored paper, Dewson regularly distributed information to women in the

party, notifying them of new programs and projects and the progress of

existing ones. Having demonstrated the usefulness of women party mem-

bers, Eleanor Roosevelt and Dewson gained equal representation for

women on the party’s 1936 platform committee and won eight slots as

party vice chairs for women, the same number as men.

The 1940 convention brought the first debate on the Equal Rights

Amendment in the party’s Resolutions and Platform Committee. At that

Democratic Party, Women in the 191

time, Eleanor Roosevelt, along with many other women in the New Deal

and women in the trade unions, opposed the measure, fearing that it

would end protective labor legislation for women. Rejecting the amend-

ment, the committee approved “the principle of equality of opportunity

for women.”

The 1944 Democratic National Convention changed its position and

endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment. Also at that convention, Dorothy

Vredenburgh became secretary of the Democratic National Committee,

the first female officer in either party. She served until 1989.

By the 1948 convention, Eleanor Roosevelt had shifted her attention

to the international arena, and Molly Dewson had retired from politics. In-

dia Edwards emerged as a leader, particularly at the 1948 national conven-

tion, where she defined inflation as a women’s issue and pointed to the

problems the escalating costs of food and clothing created for family budg-

ets. Like Dewson before her, Edwards organized women to support the

party’s candidate, President Harry Truman, and again like Dewson, Ed-

wards recommended women to serve in the administration. Edwards was

influential in obtaining several appointments for women, including Geor-

gia Neese Clark as the first female treasurer of the United States and Euge-

nie Moore Anderson as the United States’ first female ambassador, both in

1949. In 1951, Truman offered Edwards the position of chair of the party

as a reward for her labors and in recognition of her abilities. She declined,

believing that men in the party would not accept a female chairperson.

The party eliminated the Women’s Division in 1952, deciding that

the time had come to integrate women into the larger party structure.

Women protested the change, however, fearing that their role in the party

would be diminished rather than enlarged. Women were less visible in the

party for the balance of the decade, but a Republican held the presidency

and the prevailing climate of opinion encouraged women to find their

places in their homes, rather than in public life.

At the 1964 Democratic National Convention, African American

Fannie Lou Hamer captured the nation’s attention during her appeal for

justice before the party’s committee. In her testimony, Hamer described

the indignities and the beatings she had endured as a leader of the civil

rights movement in the South. Her televised speech electrified the nation,

but the credentials committee seated the white delegation. Four years

later, Hamer was one of the twenty-two African American delegates from

Mississippi at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Following the 1968 convention, the party began a period of reform,

including national rules for the selection of convention delegates, and

guidelines that called for “reasonable representation” of various groups,

including women. As preparations began for the 1972 convention, the

192 Democratic Party, Women in the

National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) argued that since women

comprised more than 50 percent of the population in most states, “rea-

sonable representation” meant that a majority of the delegates from most

states would be women. Party leaders interpreted the guidelines less

strictly but agreed that state delegations with few women in them would

have to show that the imbalance was not the result of discrimination.

Some states complied with the guidelines, and delegations from other

states faced challenges before the credentials committee, resulting in a sig-

nificant change in the percentage of women at the 1972 convention. Thir-

teen percent of the delegates to the 1968 convention had been women; in

1972, women constituted 40 percent of the delegates to the convention.

An effort to require equal representation of women at the 1976 conven-

tion failed.

At the 1972 Democratic National Convention, Doris Meissner,

NWPC executive director, and other staff members set up an office and

held informational sessions with delegates throughout the convention.

The NWPC wanted four items included in the party platform: reproduc-

tive rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, educational equity, and equal

pay. The platform did not include the reproductive rights plank, but it did

include the other three issues.

The 1972 convention was also notable for two women’s efforts to be-

come the party’s nominees, one for president and the other for vice pres-

ident. For the first time in the party’s history, an African American

woman, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm of New York, ran for the pres-

idential nomination. Chisholm’s campaign had little promise from the be-

ginning, but she received 152 votes on the first ballot. During the conven-

tion a campaign to nominate Frances (Sissy) Farenthold for the vice

presidency developed, and NWPC members organized to help her. Faren-

thold received 404 votes.

Immediately after the convention, Democratic presidential nominee

George McGovern proposed a new slate of officers for the Democratic

National Committee, including Jean Westwood of Utah for chairperson of

the party. When Westwood became the party’s chair, she was the first

woman to hold the position in either of the two major parties. Following

the fall elections and McGovern’s defeat, Robert Strauss challenged West-

wood for the position of chair and won.

Between the 1972 and 1976 conventions, state party chairpersons ex-

pressed their objections to what they described as a quota system for

women, minorities, and youth, resulting in a new reform commission.

Despite feminists’ objections, new rules were implemented that softened

the party’s policies regarding delegate selection. Only 36 percent of the

delegates to the 1976 Democratic National Convention were women.

Democratic Party, Women in the 193

Women in the NWPC formalized their work within the parties by

creating task forces for members of each party. During the 1976 conven-

tion, the Democratic Women’s Task Force regularly met with delegates, fo-

cusing their efforts on passing the equal division rule, which would re-

quire 50 percent of the delegates to be women. When likely presidential

nominee Jimmy Carter objected to it, the task force members agreed to

drop the equal division rule in exchange for his support for the Equal

Rights Amendment and a promise that he would appoint women to sig-

nificant posts in his presidential campaign and administration. Later, the

party adopted rules guaranteeing women equal division for the 1980

Democratic National Convention. One of the most compelling moments

of the 1976 convention was Texas congresswoman Barbara Jordan’s

keynote address. The first Democratic woman and the first African Amer-

ican to make an important speech to a national convention, her oratory

and her message captivated Americans across the country.

During the Carter administration, the Democratic National Com-

mittee resurrected the Women’s Division, which had been dissolved in

1952. Iowan Lynn Cutler, who had earlier run for Congress, served as a

party vice chair and ran the division. In 1985, the party again closed the

division, which meant that it no longer had its own staff or budget. Cut-

ler remained responsible for women’s activities in addition to other areas.

At the 1980 Democratic National Convention, Democratic Party

feminists established themselves as a force within the party, even though

their leaders did not uniformly support the party’s nominee, incumbent

President Jimmy Carter. Almost 50 percent of the delegates were women,

and about 20 percent of the delegates belonged to the NWPC or the Na-

tional Organization for Women (NOW). The party platform included

strong ERA and prochoice planks.

By the 1984 convention, the Democratic Party had aligned itself with

feminist issues, a position that contrasted with that of the Republican Party,

which had essentially repudiated feminist issues. With the Democratic

Party’s allegiance to feminist issues established, feminists turned their at-

tention to nominating a woman for vice president. Before the convention

opened, likely Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale an-

nounced that Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro would be his running

mate. Mondale and Ferraro lost in the November election, but her presence

on the ticket gave unprecedented visibility to an American political woman.

The contrasts on women’s issues that developed between the two ma-

jor parties in the 1970s became heightened in the 1980s and by the 1990s

were firmly established. The Democratic Party had accepted the feminist

agenda, and equal representation within the delegations had become well

established. The gender gap—with women more likely to vote for

194 Democratic Party, Women in the