Satas D., Tracton A.A. (ed.). Coatings Technology Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

52

250

200

Separation

in

Angstrom

Units

100

50

20

1

DAHLQUIST

10

100

Force

Constant

l000

Figure

4

Attraction between ideally planar

solids.

could be approximated quite well by the geometric mean of the works of cohesion

of

the

two liquids when the only attractive forces of cohesion are dispersion forces:

W,,

=

2(YIJl,J

I

l2

However, in some liquid pairs (e.g., water and hydrocarbons), this did not hold, and they

coined an “interaction parameter,”

Q,

given by

For water on

a

paraffinic hydrocarbon, where the contact angle is log”,

Q,

would

have a value of about

0.55.

For hexadecane on polyethylene,

Q,

is very near unity. Good

and his associates”.” have provided directions for calculating

Q,

and they give experimen-

tal and calculated values for several combinations

of

water and organic liquids.

FowkesI3 approached the problem from

a

different point of view. He reasoned that

the only forces operable at the interface between water and an aliphatic hydrocarbon

molecule contains no hydrogen bonding groups and no fixed dipoles.

THE THEORY

OF

ADHESION

53

Fowkes also assumed that the work of adhesion would be given by twice the geomet-

ric mean

of

the surface energies of the two liquids on either side of the interface, but now

taking into consideration only the dispersion force components of the surface energies.

For the work of adhesion between water

(LI)

and n-octane

(L2).

we have

W,,

=

2(Y;,Y:j,)”’

=

YL,

+

YL,

-

YL,L,

where the superscript

D

stands for the dispersion energy component of the total surface

energy. Accepted values for the surface energies and interfacial energies are:

yr.,

=

72.8 ergdcm’;

yL.

=

$!,

=

21.8 ergdcm’; y12,r.2

=

50.8 ergs/cm’

If these values are substituted into the equation above to solve for

YE,”,

we get 22.0 ergs/

cm’. Fowkes evaluated several water-aliphatic hydrocarbon systems and found that they

all yielded essentially the same value for the dispersion energy component of the surface

energy of water, 21.8

*

0.7 ergdcm’.

Turning now to the work

of

adhesion and the interfacial energy between mercury

and aliphatic hydrocarbon, Fowkes calculated the dispersion energy component of the

surface energy

of

mercury.

Using n-octane as the hydrocarbon liquid having

a

surface energy of 21.8 ergdcm’

(all

of

it attributed to dispersion forces), the surface energy of mercury, 484 ergskm’, and

the interfacial energy, 375 ergskm’, we have

W,,

=

2(Y~gY~-oct)”’

=

YH,s

+

Y,IPOCt

-

Y(H,S.,l

-<)cl)

W,,

=

2($$

X

21.8)”’

=

484

+

21

.8

-

375

=

196.2

The average for

a

series of mercury-aliphatic hydrocarbon systems yielded 200

2

7

ergs/cm’ for the dispersion energy component of the surface energy of mercury.

Since the remaining forces that contribute

to

the surface energy of mercury are

metallic forces, the only interacting forces at the water-mercury interface are the dispersion

forces, and the work of adhesion is given by:

W,,

=

2(200

X

21.8)”’

=

484

+

72.8

-

Y(H,,

H,())

from which

Y,~,,

f.l,O)

=

424.7 ergs/cm’

This compares very favorably with the measured value of 426 ergskm’.

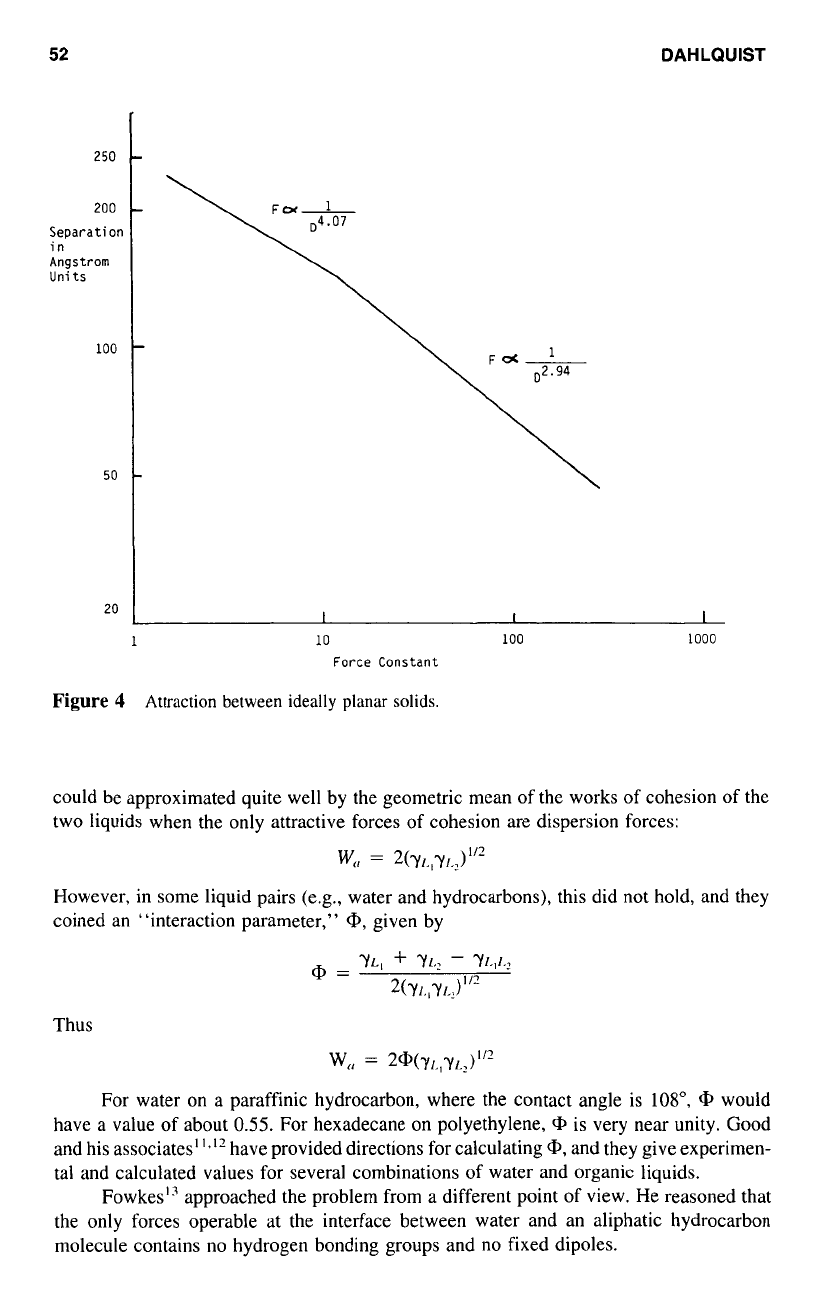

The work of adhesion due to dispersion forces is numerically small in work or

energy units. For example, the work of adhesion of methylene iodide on polyethylene is

82 ergskm’

(0

=

52”). This small value is not, however, indicative

of

a

small force of

attraction across the interface. Keep in mind that the work is the product of force and

displacement, and that the attractive force, at separation distances less than

50

A

(5

X

10”

cm) increases

as

the inverse of displacement raised

to

the third power (Fig.

4).

The molecules at the interface are at an equilibrium distance of separation where

attractive forces and repulsive forces balance. The variation

in

the repulsive forces with

distance

of

separation has a dependence several orders of magnitude higher than the attrac-

tive forces (of the order of

10”

for atom pairs and

10’

for repulsion forces across a

hypothetical plane). We can calculate the maximum force

of

attraction by equating the

work of adhesion

to

the work of separation.

54

DAHLQUIST

Let

F,,

indicate the attractive force,

F,

the repulsive force, x the distance separation,

and d the equilibrium distance. We cannot measure d directly, but we can estimate it from

calculations

of

the distance between molecular centers in

a

liquid of known specific gravity

and molecular weight. In the case

of

methylene iodide (sp

g

3.325, mol wt

267.9)

we

calculate the separation to be about

5

X

lov8

cm between the centers of adjacent mole-

cules.

If we take

5

X

lo-’ cm

as

a

reasonable distance of separation across the interface

between methylene iodide and polyethylene, and we accept the force versus distance

relationships for attraction

(a)

and repulsion

(r)

we can write:

where the subscript

e

stands for “equilibrium.” At equilibrium we have the condition

that

(F(,)(,

=

(F,.)<..

We can then express the work of adhesion as

The solution is

For methylene iodide on polyethylene,

W,,

is 82 ergdcm’. Taking

d

as

5

X

IO-’

cm,

F,,

=

F

=

F,.

=

4.92

x

lo9

dyneskm’.

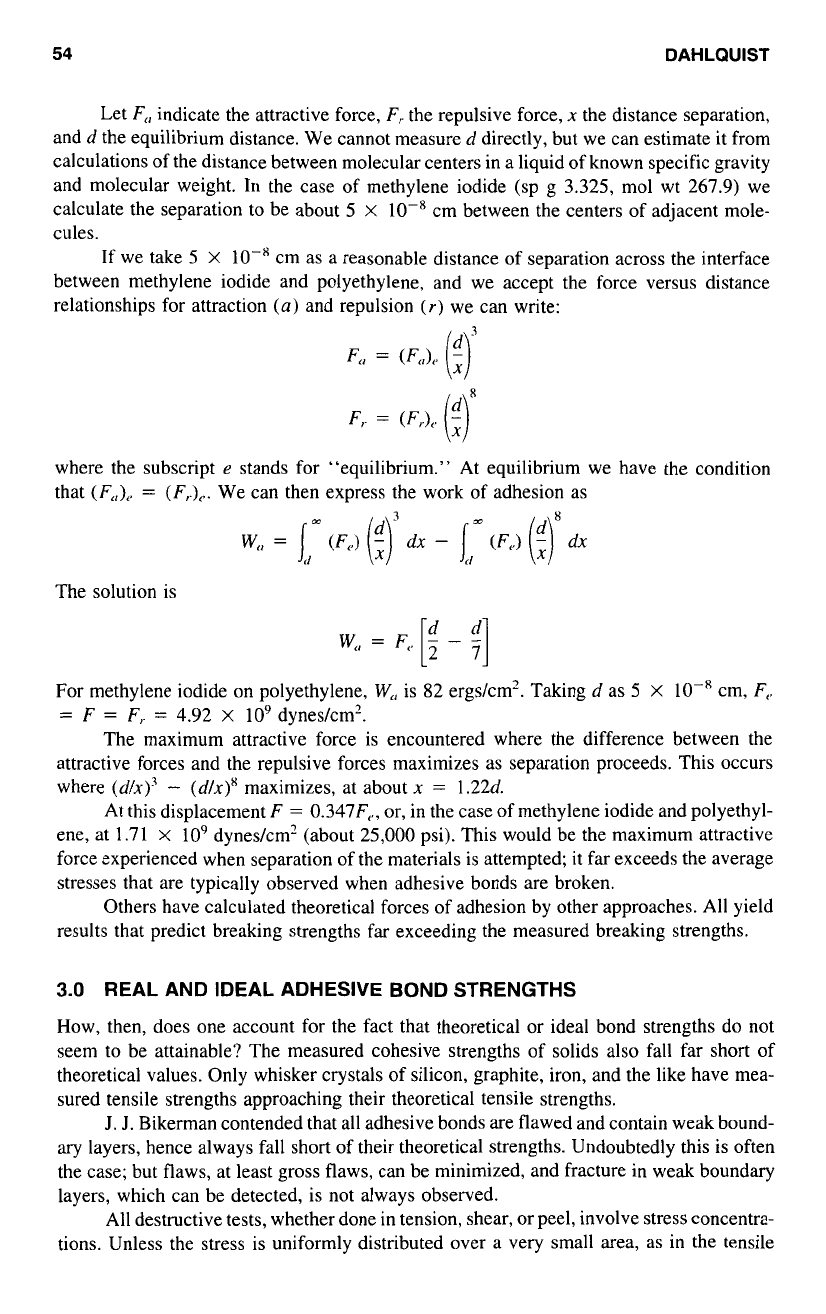

The maximum attractive force is encountered where the difference between the

attractive forces and the repulsive forces maximizes

as

separation proceeds. This occurs

where (d/x)3

-

(d/~)~ maximizes, at about x

=

1.22d.

At this displacement

F

=

0.347F,.,

or, in the case of methylene iodide and polyethyl-

ene, at

1.71

X

lo9

dyneskm’ (about 25,000 psi). This would be the maximum attractive

force experienced when separation of the materials is attempted; it far exceeds the average

stresses that are typically observed when adhesive bonds are broken.

Others have calculated theoretical forces of adhesion by other approaches. All yield

results that predict breaking strengths

far

exceeding the measured breaking strengths.

3.0

REAL AND IDEAL ADHESIVE BOND STRENGTHS

How, then, does one account for the fact that theoretical or ideal bond strengths do not

seem to be attainable? The measured cohesive strengths of solids

also

fall far short

of

theoretical values. Only whisker crystals of silicon, graphite, iron, and the like have mea-

sured tensile strengths approaching their theoretical tensile strengths.

J.

J.

Bikerman contended that all adhesive bonds are flawed and contain weak bound-

ary layers, hence always fall short

of

their theoretical strengths. Undoubtedly this is often

the case; but flaws, at least gross flaws, can be minimized, and fracture in weak boundary

layers, which can be detected, is not always observed.

All destructive tests, whether done in tension, shear, or peel, involve stress concentra-

tions. Unless the stress is uniformly distributed over

a

very small area, as in the tensile

THE THEORY

OF

ADHESION

55

25

20

X

W

E

V

\

a,

S

V

z1

v)

a,

v)

.W

L

v)

a,

L

3

15

10

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

Thickness

of

adhesive

layer,

cm.

Figure

5

Adhesive layer thickness

and

strength

of

butt joints.

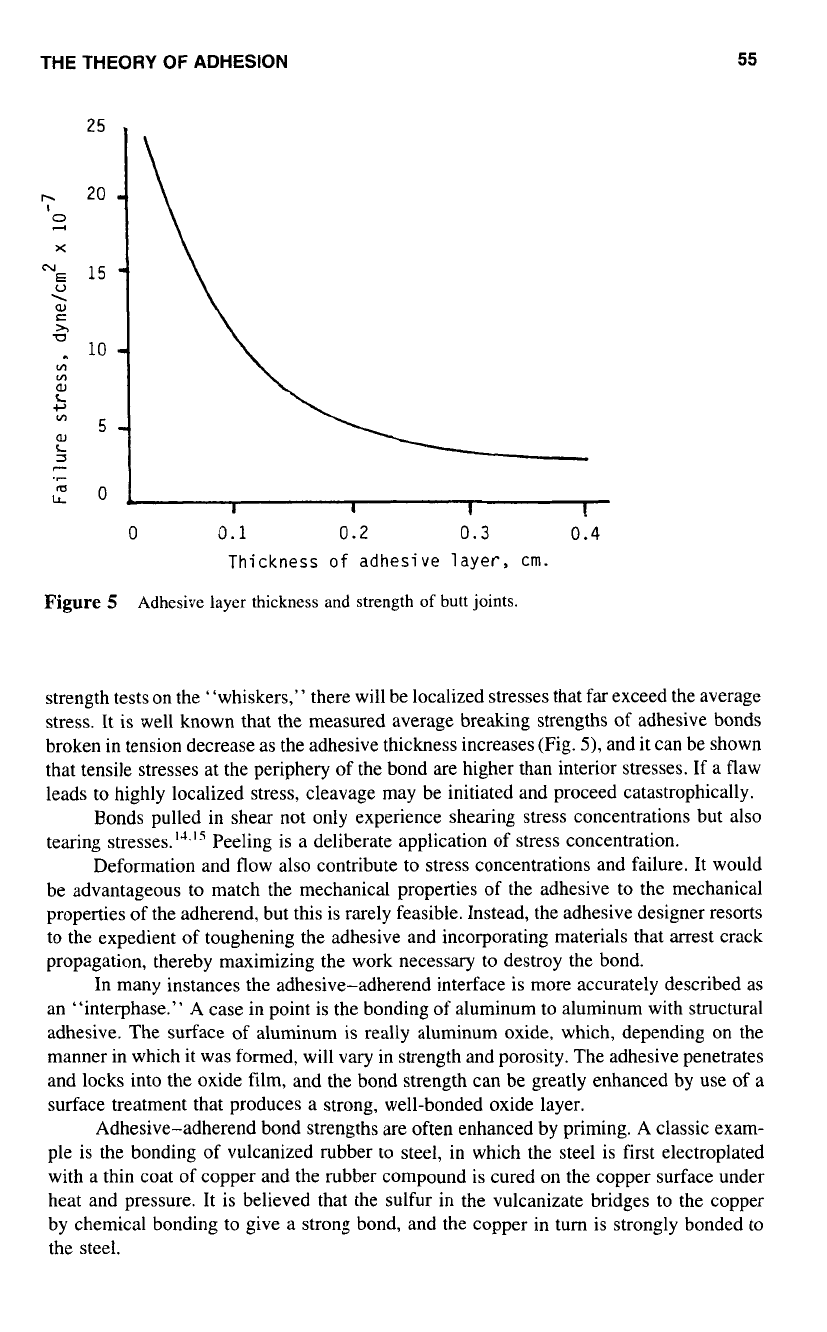

strength tests on the “whiskers,” there will be localized stresses that far exceed the average

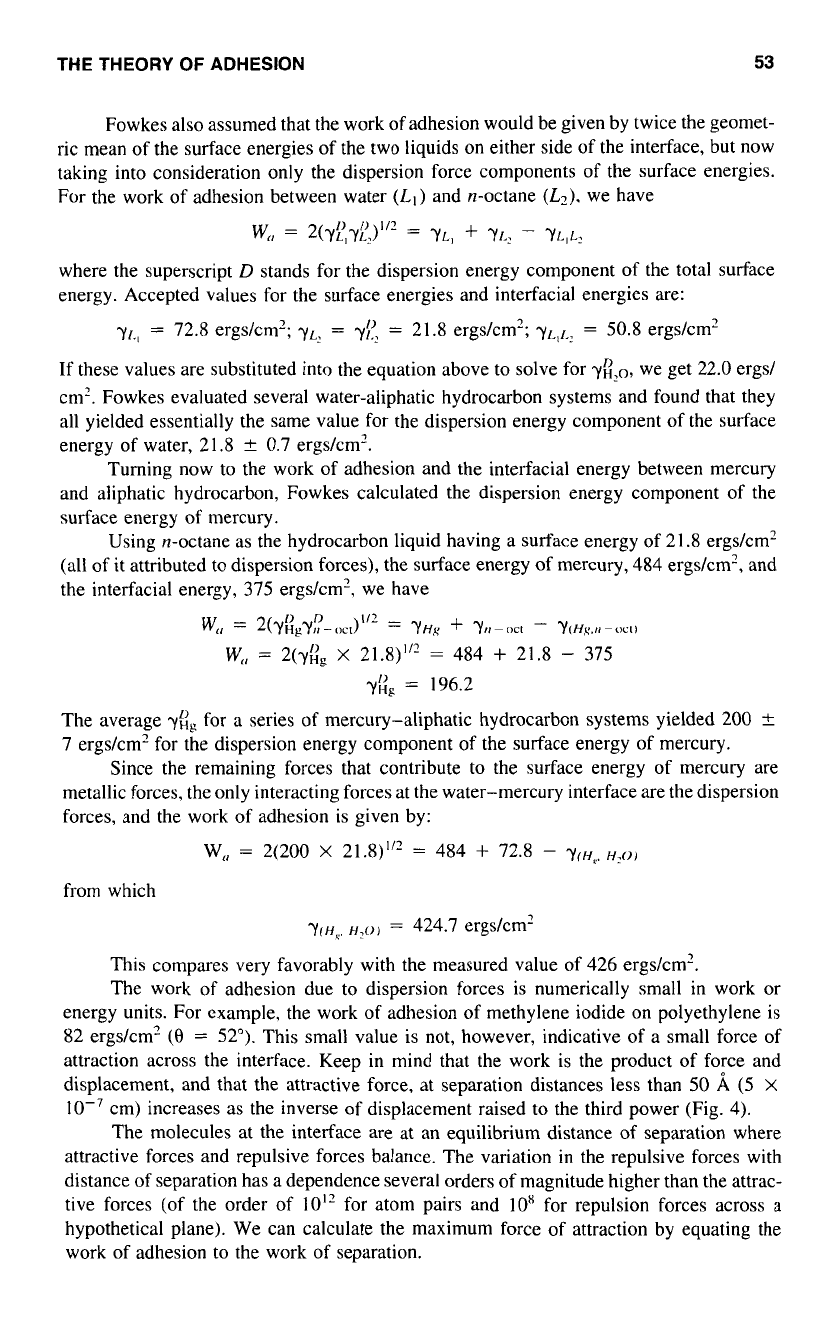

stress. It is well known that the measured average breaking strengths of adhesive bonds

broken in tension decrease

as

the adhesive thickness increases (Fig.

5),

and it can be shown

that tensile stresses at the periphery

of

the bond are higher than interior stresses. If

a

flaw

leads to highly localized stress, cleavage may be initiated and proceed catastrophically.

Bonds pulled in shear not only experience shearing stress concentrations but also

tearing stresses.’4.’s Peeling is a deliberate application of stress concentration.

Deformation and flow also contribute to stress concentrations and failure. It would

be advantageous to match the mechanical properties of the adhesive to the mechanical

properties of the adherend, but this is rarely feasible. Instead, the adhesive designer resorts

to the expedient of toughening the adhesive and incorporating materials that arrest crack

propagation, thereby maximizing the work necessary to destroy the bond.

In many instances the adhesive-adherend interface is more accurately described as

an “interphase.” A case in point is the bonding

of

aluminum to aluminum with structural

adhesive. The surface

of

aluminum is really aluminum oxide, which, depending on the

manner in which it was formed, will vary in strength and porosity. The adhesive penetrates

and locks into the oxide film, and the bond strength can be greatly enhanced by use

of

a

surface treatment that produces a strong, well-bonded oxide layer.

Adhesive-adherend bond strengths are often enhanced by priming. A classic exam-

ple is the bonding of vulcanized rubber to steel, in which the steel is first electroplated

with a thin coat of copper and the rubber compound is cured on the copper surface under

heat and pressure. It is believed that the sulfur in the vulcanizate bridges to the copper

by chemical bonding to give

a

strong bond, and the copper in turn is strongly bonded to

the steel.

56

DAHLQUIST

Priming is often used on bonding adhesives to plastic films. For example, the first

transparent pressure-sensitive tape, which comprised a cellophane film and a natural rubber

rosin adhesive, would undergo separation of the adhesive from the film under humid

conditions. The problem was solved by first applying to the cellophane,

a

thin prime coat,

a

blend of natural rubber and casein, then coating the adhesive over the primer.

Surfaces notoriously difficult to bond to, such

as

polyethylene, polypropylene, and

Teflon, are modified by treatments that make the surfaces more polar and possible chemi-

cally active, for example, by corona, plasma, or chemical treatments. These treatments

may also remove weak boundary layers.

Though strong, durable adhesive bonds are usually the goal of adhesive technology,

there is also a need for bonds that are deliberately made weak. This need arises in the

pressure-sensitive tape industry, where it is desirable to have tape that unwinds easily

from the roll, and especially where pressure-sensitive adhesives are to be transferred from

a

carrier film to another surface. The surfaces that provide easy release typically have low

critical surface energies, almost totally dominated by the “dispersion energy” component.

Also,

for release coatings to function well, there must be no mutual solubility between

them and the adhesives. Silicone release coatings, which consist mainly

of

polydimethyl

siloxane, provide the easiest release. They have low critical surface energies, though not

as low

as

certain fluorocarbon polymers. They

also

have

a

high degree of incompatibility

with the pressure-sensitive adhesives that release well from them, but these criteria alone

do not explain the low level of adhesion. In addition, they differ from other release coatings

by being soft and elastic rather than hard. This feature may serve to enhance the stress

concentration when the adhesive is separated from the release liner.

In conclusion, adhesive bond strengths measured by destructive tests will never

approach theoretical values, but the intrinsic attractive forces can be manipulated by the

choice of materials and surface treatments

to

produce a wide range of practical bond

strengths.

REFERENCES

1. T. Young,

Phil.

Trcrns.

R.

Soc.

London,

95,

65 (1805).

2.

W.

D.

Harkins and

H.

K.

Livingston,

J.

Chern.

Phys.,

10,

342 (1942).

3.

A.

DuprC,

ThPorie MPcnnique

de

Icr

Chleur,

Paris,

1869.

p.

393.

4.

W.

A.

Zisman,

lnd.

Eng.

Chetn.,

55.

18 (1963).

5.

E.

G. Shafrin, in

Polymer

Handbook,

J.

Brandrup and E.

M.

Irnrnergut, Eds. New York: Wiley-

6.

F. London,

Trcrns. Ftrrcrelay

Soc..

33.

8

(1936).

7.

R.

S.

Drago, L. B. Parr, and C.

S.

Chamberlain,

J.

Anr.

Chetn.

Soc.,

99,

3203 (1977).

8.

F.

M.

Fowkes,

J.

Ar1ke.s.

Sci.

Techno/..

1.

7 (1987).

9.

H.

B.

C.

Casirnir

and

D.

Polder,

Phvs.

Ret,..

73,

360 (1948).

10.

E.

M.

Lifshitz,

C.

R.

Acnd.

Sci.

USSR,

97,

643

(

1954).

11.

D.

Tabor and R.

N.

S.

Winterton,

Nature,

219,

1120 (1968).

12.

L.

A.

Girifalco and R.

J.

Good,

J.

Phys.

Chetn.,

61,

904 (1957).

13.

F.

M.

Fowkes,

J.

Phys.

Chem.,

66,

382 (1962).

14.

0.

Volkersen,

Luftfirhrforschung,

15,

41 (1938).

15.

M.

Goland and

E.

Reissner,

J.

Appl.

Mech.,

Trcrns.

ASME.

66,

17 (1944).

Interscience,

1966,

pp.

1 1

1-1

13.

Adhesion Testing

Ulrich

Zorll

Forschung.sinstitut fir Pigmente

und

Lrrcke,

Stuttprt, Germanv

1

.O

FUNDAMENTALS OF ADHESION

Without sufficient adhesion,

a

coating

of

otherwise excellent properties in terms

of

resis-

tance to weather, chemicals, scratches, or impact would be rather worthless. It is therefore

necessary to provide for good adhesion features when paint materials

are

formulated.

There must also be adequate means for controlling the level of adhesion strength after the

coating has been spread and cured

on

the substrate. Moreover, methods should be available

that allow for the detection of any failure in the case of the dissolution of the bond between

coating and substrate, under any circumstances whatsoever.

1

.l

Components at the Interface

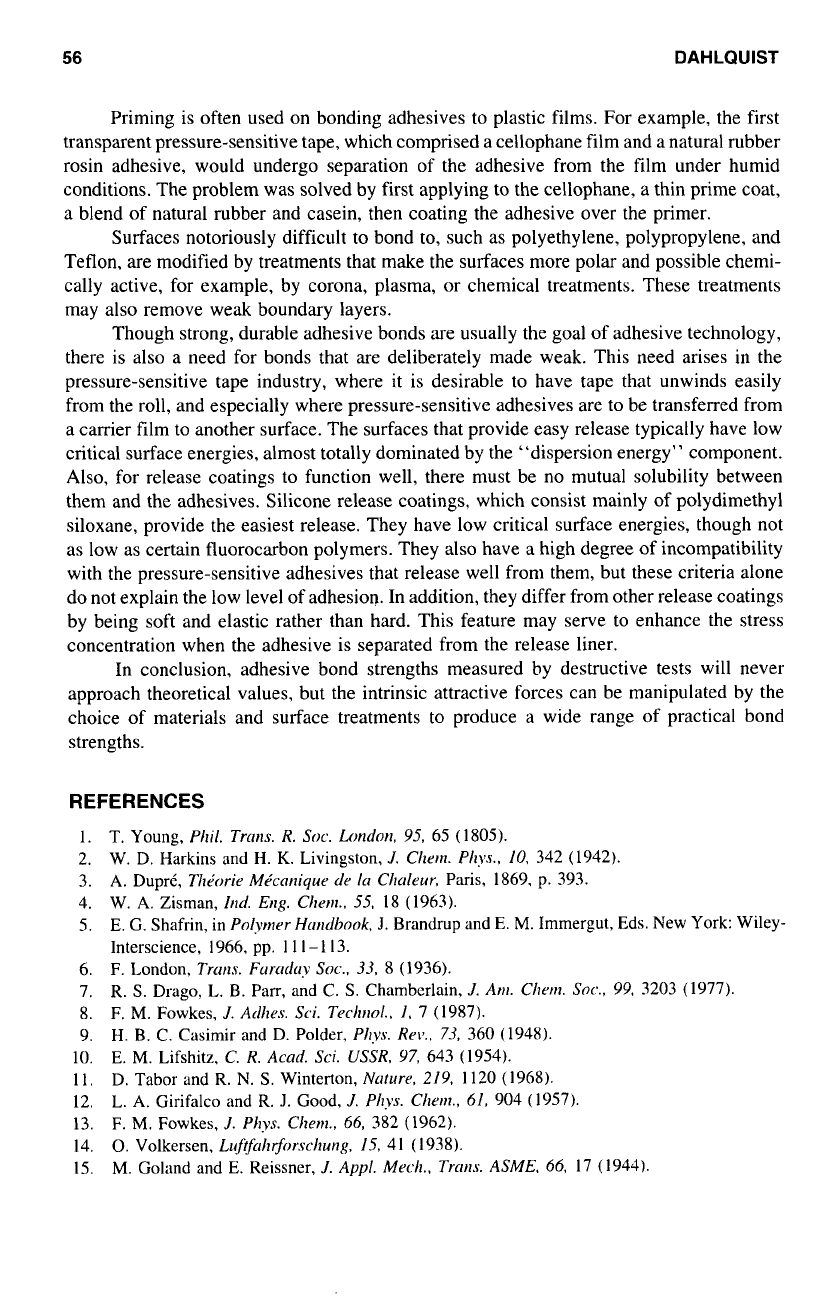

In chemical terms, there is

a

considerable similarity between paints on one side and adhe-

sives or glues on the other (Fig.

1).

Both materials appear in the

form

of organic coatings;

thus it is appropriate in this chapter to concentrate on the behavior of paint materials.

Adhesion is the property requested in either case, though perhaps with different emphasis

on its intensity, according to the intended use.

Such a coating is, in essence,

a

polymer consisting of more or less cross-linked

macromolecules, and

a

certain amount of pigments and fillers. Metals, woods, plastics,

paper, leather, concrete, or masonry, to name only the most important materials can form

the substrate for the coating.

It is, however, important to keep in mind that these substrate materials may inhibit

a

rigidity higher than that of the coating. Under such conditions, fracture will occur within

the coating, if the system experiences external force of sufficient intensity. Cohesive failure

will be the consequence, however, if the adhesion at the interface surpasses the cohesion

of the paint layer. Otherwise, adhesive failure is obtained, indicating

a

definite separation

between coating and substrate.

57

58

ZORLL

The energetic aspects at the interface and the effects of elasticity within coating and

substrate have been taken into consideration for

a

theoretical approach, on which it is

possible to base predictions

of

where failure will occur.'

Both types of adhesion damage are encountered in practice. The existence of cohe-

sion would signal the attainment of an optimum adhesion strength. Any further improve-

ment of the systems should then be sought in the direction of increasing the inherent

strength

of

the coating material.

1.2

Causes

of

Failure

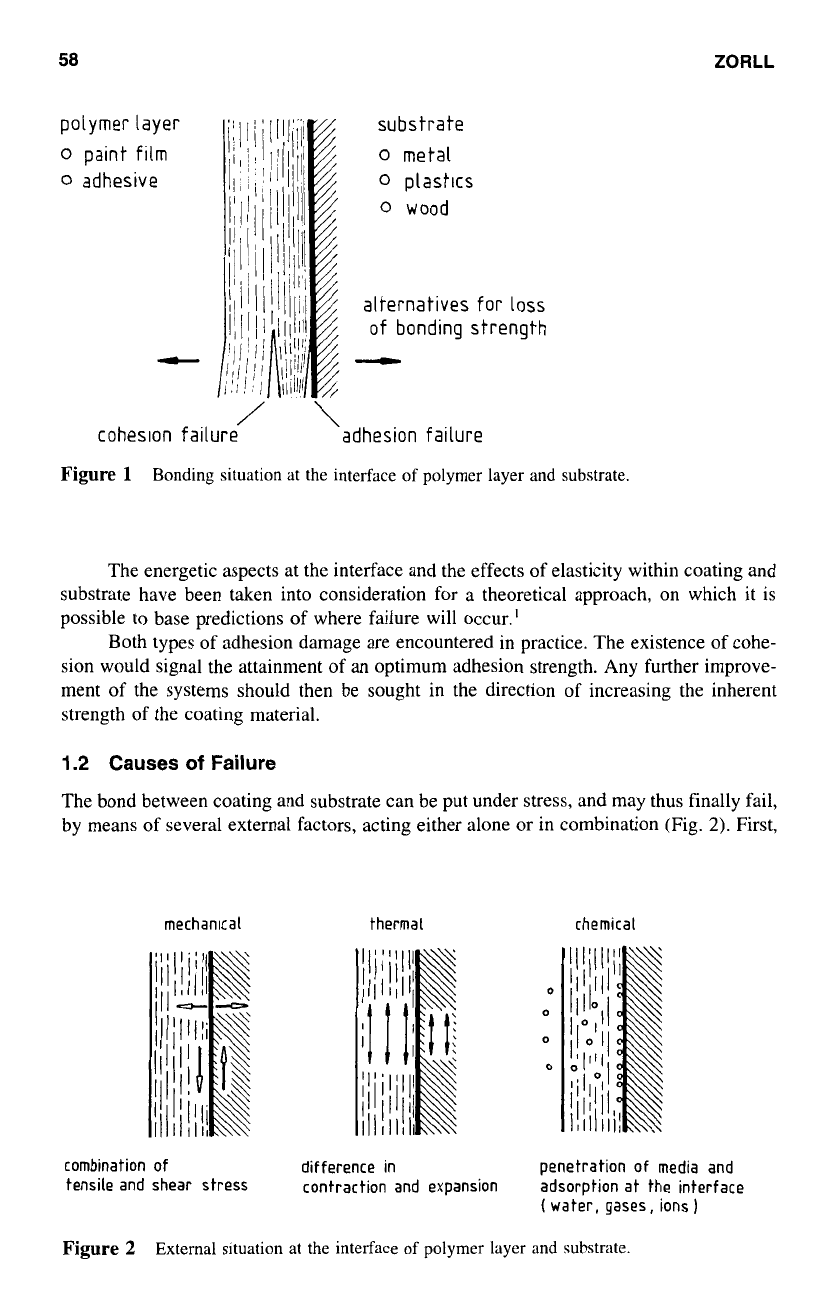

The bond between coating and substrate can be put under stress, and may thus finally fail,

by means of several external factors, acting either alone

or

in combination (Fig.

2).

First,

mechanlcal thermal chemical

combination of

difference

in

penetration

of

media and

tensile and shear stress

contraction and expansion

adsorption at the interface

(

water, gases, ions

1

Figure 2

External situation at the interface

of

polymer layer and substrate.

ADHESION TESTING

59

there may be regular mechanical stress, affecting not only the bulk of the materials but

also the bond strength at the interface. It is useful here

to

distinguish between the two

most common types of stress: tensile stress, effective perpendicularly to the interface, and

shear stress, appearing along the plane

of

contact.

Moreover, since coatings may undergo changes in temperature, sometimes even

rather rapidly, any difference in the coefficient

of

expansion can cause at the interface

stress conditions of such high intensity that the paint film becomes detached from the

substrate. This event may be especially disadvantageous because the temperature effects

tend to be less obvious than the mechanical and chemical factors.

There may be, of course, an effect of

a

chemical, which penetrates through the

coating and becomes absorbed at the interface, causing

loss

of adhesion here.

It is always useful to take these effects into consideration when adhesion must

be measured, because the method of testing the coating should reproduce the end-use

conditions.

1.3

Measures

of

Adhesion

There are various possibilities for characterizing the results obtained in an adhesion test.

If it is necessary to evaluate the bonding strength at the interface, the quantity to be

measured

is

obviously the maximum mechanical stress that can be attained at the interface.

This is adhesion strength in the strict sense, expressed

as

force per unit area, and specified

as

either tensile or shear stress. Consequently, in several test methods, the result is obtained

in that form.

The energy that must be provided for breaking the bond at the interface can

also

be an informative quantity. It is expressed

as

work

of

adhesion and is formally equivalent to

the product of adhesion strength,

as

defined earlier, and the distance between the separated

surfaces of coating and substrate immediately after detachment. Thus, that quantity has

the dimensions

of

force per unit length, and this is exactly the value obtained with some

other test methods e.g., the peeling test.

2.0

STANDARDIZATION

OF

ADHESION TESTS

Since

a

specification for the degree of adhesion must be provided in nearly each paint

formulation, it is not surprising that methods for routine measurement of that key quantity

have been established in the field of quality testing. This is true for the cross-cut test. the

paint technicians’ first choice when adhesion must be estimated. However, the cross-cut

test is nowadays more and more complemented by the pull-off methods.

Both methods have been the subject of national standardization. However, the differ-

ences in the documents of various countries are of minor importance, and it was relatively

easy to formulate international standards, ensuring that these fundamental tests can be

carried out in a uniform manner.

2.1

Cross-Cut Test

Scope and procedure of practical and instructive method have been laid down by the

International Organization for Standardization

(ISO).’

To obtain an idea of the adhesion

of the coating,

a

lattice pattern is cut into it, penetrating through the film and into the

substrate. Various cutting tools can be used either manually or mechanically for this

60

ZORLL

appearance of

cross-cut area

percentage

of

flaking

0%

<

5

O/O

<

15

‘/o

35%

<

65

‘10

classification

0

1

2

3

4

Figure 3

Principle of classifying paint film adhesion in the cross-cut test.

purpose. A good choice is the multiple cutting tool,

a

set of six “knives,”

1

or

2

mm

apart, yielding

a

uniform pattern.

The test results are evaluated according

to

the scheme indicated in Figure

3.

The

classification is based on estimating the amount of paint flakes separated from the substrate.

If in doubt about the real percentage of detachment, one may brush off the loose parts,

or remove them by means

of

an adhesive tape.

It is not always necessary to base the judgment about the degree of adhesion on the

whole six-step classification. The

IS0

recommends standard considering the test for “go-

no go” statements. In such case, class

“0”

would indicate perfect adhesion, whereas class

“2.”

or even class

“

1

,”

should be interpreted as an objectionable result. All higher classes

would then signal, although with different distinctness, that something must be done to

improve the coating’s adhesion.

2.2

Tensile Methods

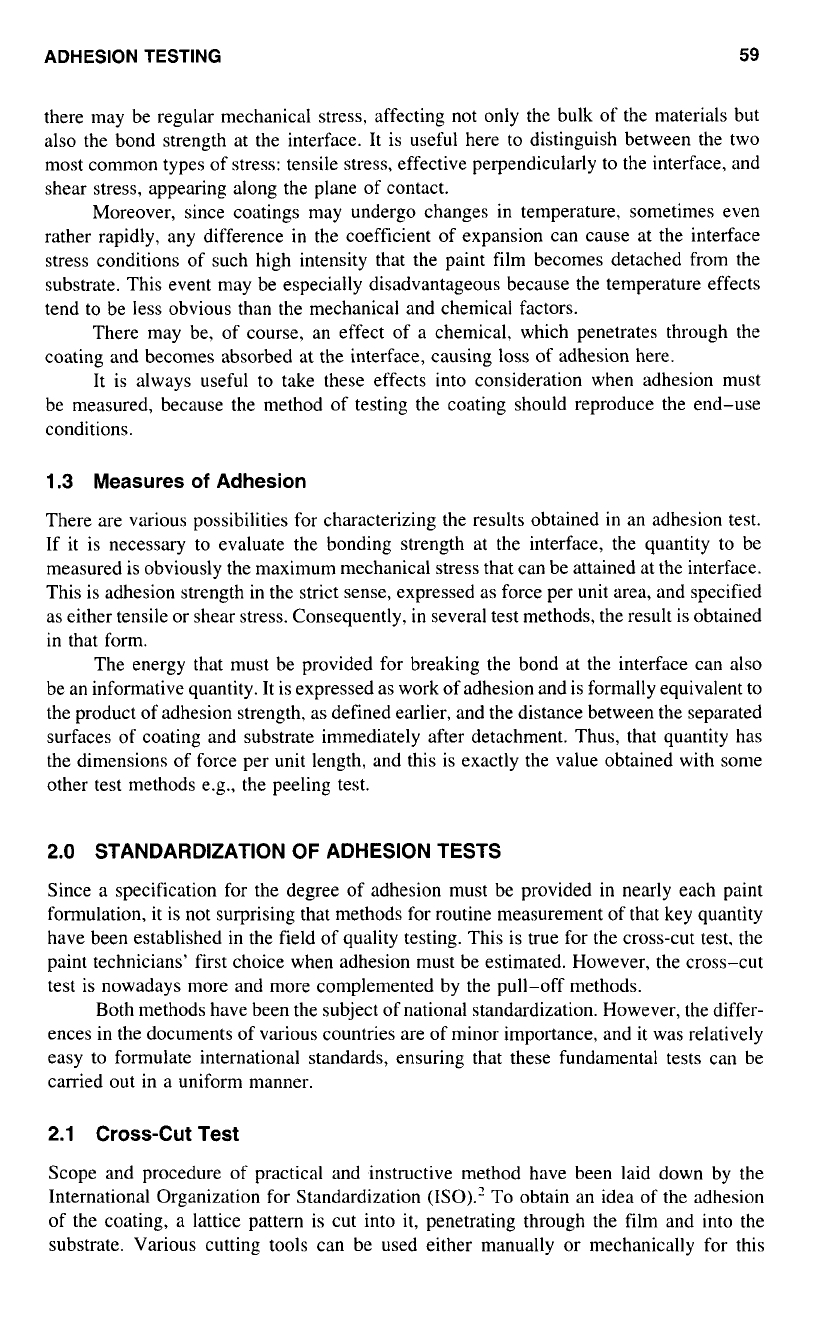

The typical stress patterns at the interface, caused by loads acting predominantly either

normal or parallel to the plane of contact, have been used as the basis for pertinent test

methods (Fig.

4).

The pull-off method is the most widely used procedure and has already

been standardized internationally.’

As

a

preparation for the test,

a

stud, normally made

of steel. is glued with the coating and is subjected

to

axial tension until detachment of

the paint film occurs. The result i.e., the adhesion strength is the maximum tensile stress

that is possible at the interface.

If, however, a torque is applied about the axis

of

the stud, the process of detachment

reveals the maximum shear stress that can be attained at the interface, thus also leading

to

a

characteristic measure of adhesion.

It has been shown‘ that the value

of

adhesion strength obtained from either method

are of the same order

of

magnitude. However, there is a tendency to obtain results with

the torque principle in the case of cohesive failure, but lower results for adhesive failure.

The accuracy, with which the tests can be carried out, and the existence

of

a

well-

defined mechanical principle for them, must not, however, lead

to

the idea that the values

obtained in this way can be considered to be material constants for the bonding components.

There is, instead, an additional influence

of

several parameters, such

as

temperature, speed

of

deformation, and even form and size of the stud.

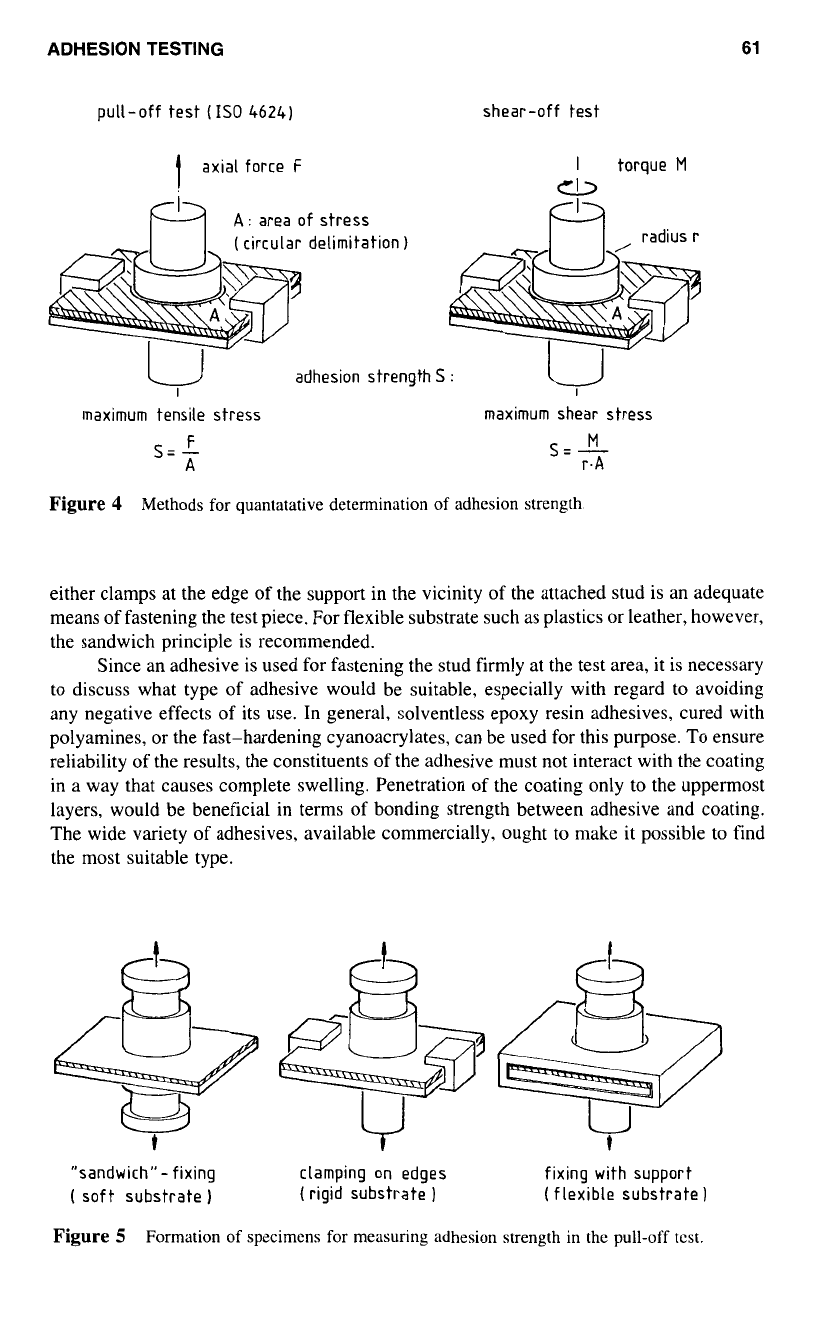

Also of importance are the rigidity

of

the test piece and the possibility of securing

it for measurement.’ As shown in Figure

5,

for coatings on undeformable substrates, using

ADHESION TESTING

61

pull-off test

(IS0

46241

shear-off test

1

axial force

F

I

torque

M

CI,

A:

area of stress

(

circular delimitation

1

radius

r

adhesion strength

S

:

I

I

maximum tensile stress maximum shear stress

F

M

S=-

A

S=

-

r.A

Figure

4

Methods

for

quantatative determination

of

adhesion strength.

either clamps at the edge of the support in the vicinity of the attached stud is an adequate

means of fastening the test piece. For flexible substrate such as plastics or leather, however,

the sandwich principle is recommended.

Since an adhesive is used for fastening the stud firmly at the test area, it is necessary

to

discuss what type

of

adhesive would be suitable, especially with regard

to

avoiding

any negative effects

of

its use. In general, solventless epoxy resin adhesives, cured with

polyamines, or the fast-hardening cyanoacrylates, can be used for this purpose.

To

ensure

reliability

of

the results, the constituents of the adhesive must not interact with the coating

in a way that causes complete swelling. Penetration of the coating only to the uppermost

layers, would be beneficial in terms of bonding strength between adhesive and coating.

The wide variety of adhesives, available commercially, ought to make it possible to find

the most suitable type.

t

"sandwich"- fixing

clamping on edges fixing with support

(

soft substrate

1

(rigid substrate

) (

flexible substrate

1

Figure

5

Formation

of

specimens

for

measuring adhesion strength in the

pull-off

tcst.