Sandau R. Digital Airborne Camera: Introduction and Technology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

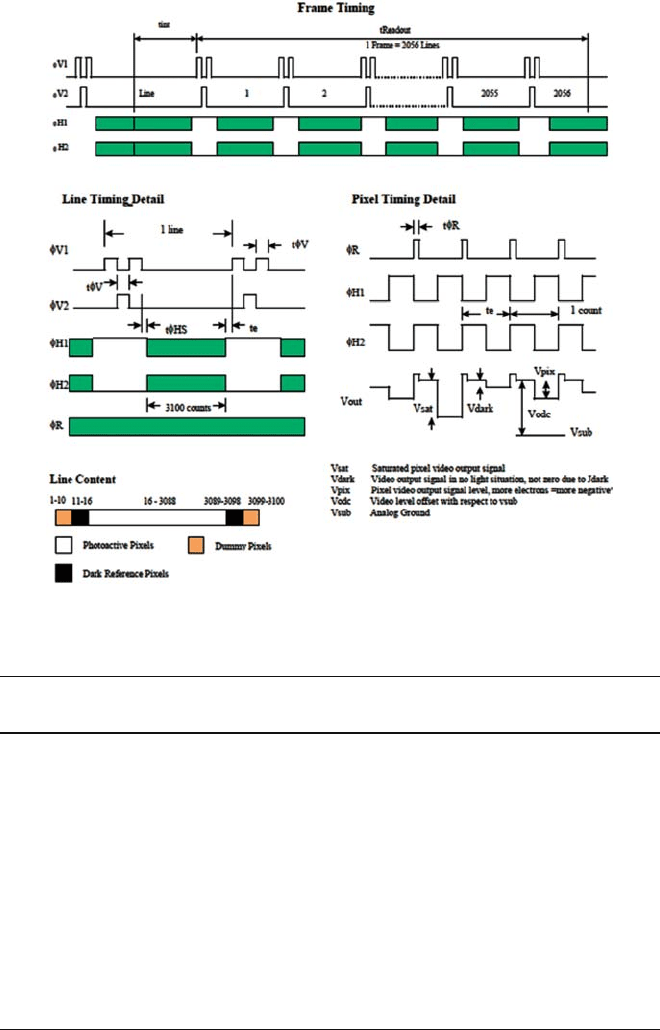

214 4 Structure of a Digital Airborne Camera

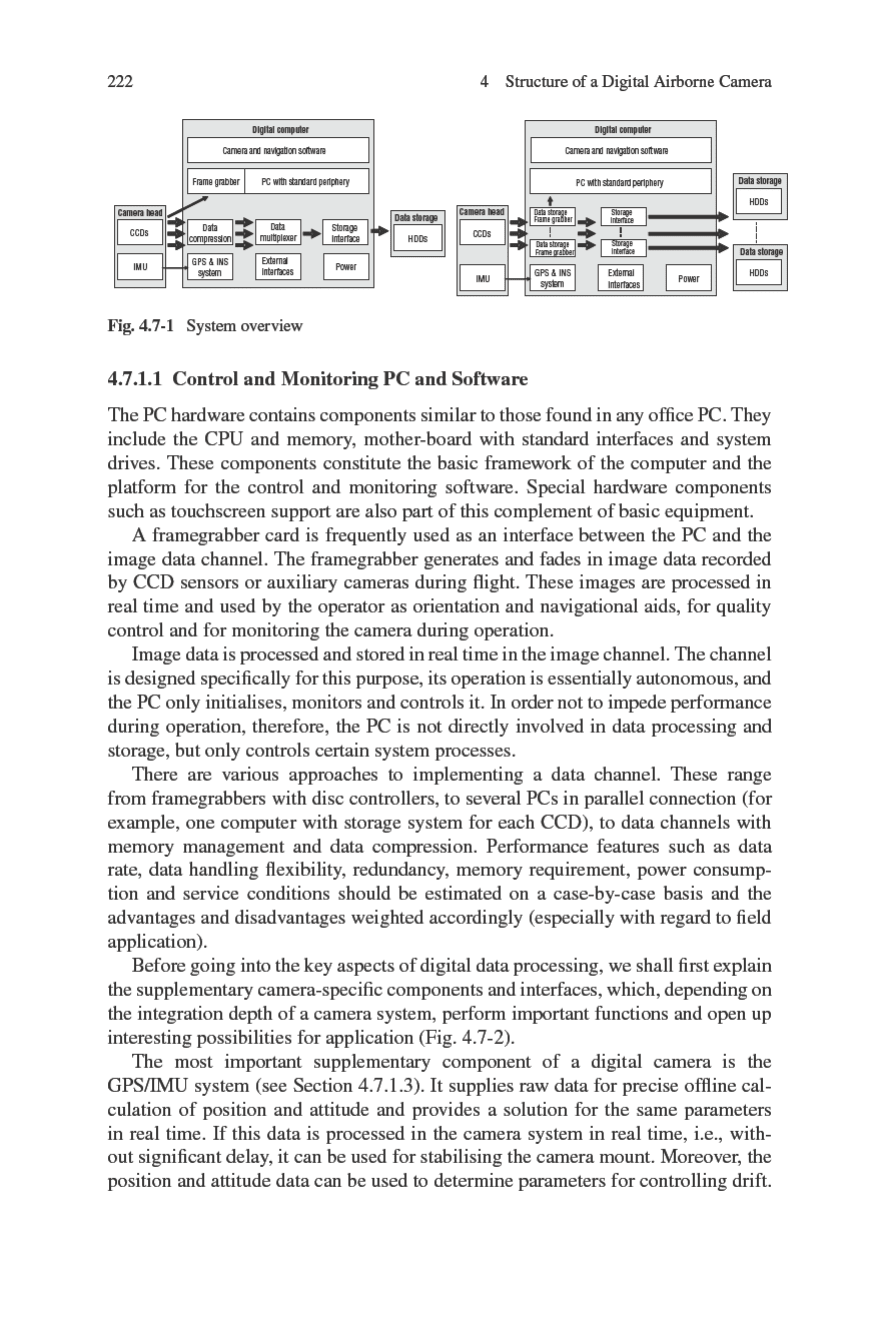

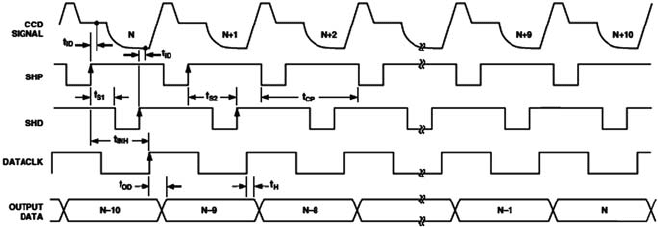

Fig. 4.6-2 Timing details for the KAF-6303LE sensor (Kodak, 1999)

Table 4.6-1 Relationships between levels of clock signals of the KAF-6303LE sensor (Kodak,

1999)

Description Symbol Level Min. Nom. Max. Units

Effective

capacitance

Vertical CCD

Clock – Phase 1

φ V1 Low −10.5 −10.0 −9.5 V 820 nF (all φV1

pins)

High 0.5 1.0 1.5 V

Vertical CCD

Clock – Phase 2

φV2 Low −10.5 −10.0 −9.5 V 820 nF (all φV2

pins)

High 0.5 1.0 1.5 V

Horizontal CCD

Clock – Phase 1

φH1 Low −6.0 −4.0 −3.5 V 200 pF

High 4.0 6.0 6.5 V

Horizontal CCD

Clock – Phase 2

φH2 Low −6.0 −4.0 −3.5 V 200 pF

High 4.0 6.0 6.5 V

Reset Clock φRLow−4.0 −3.0 −2 V 10 pF

High 3.5 4.0 5.0 V

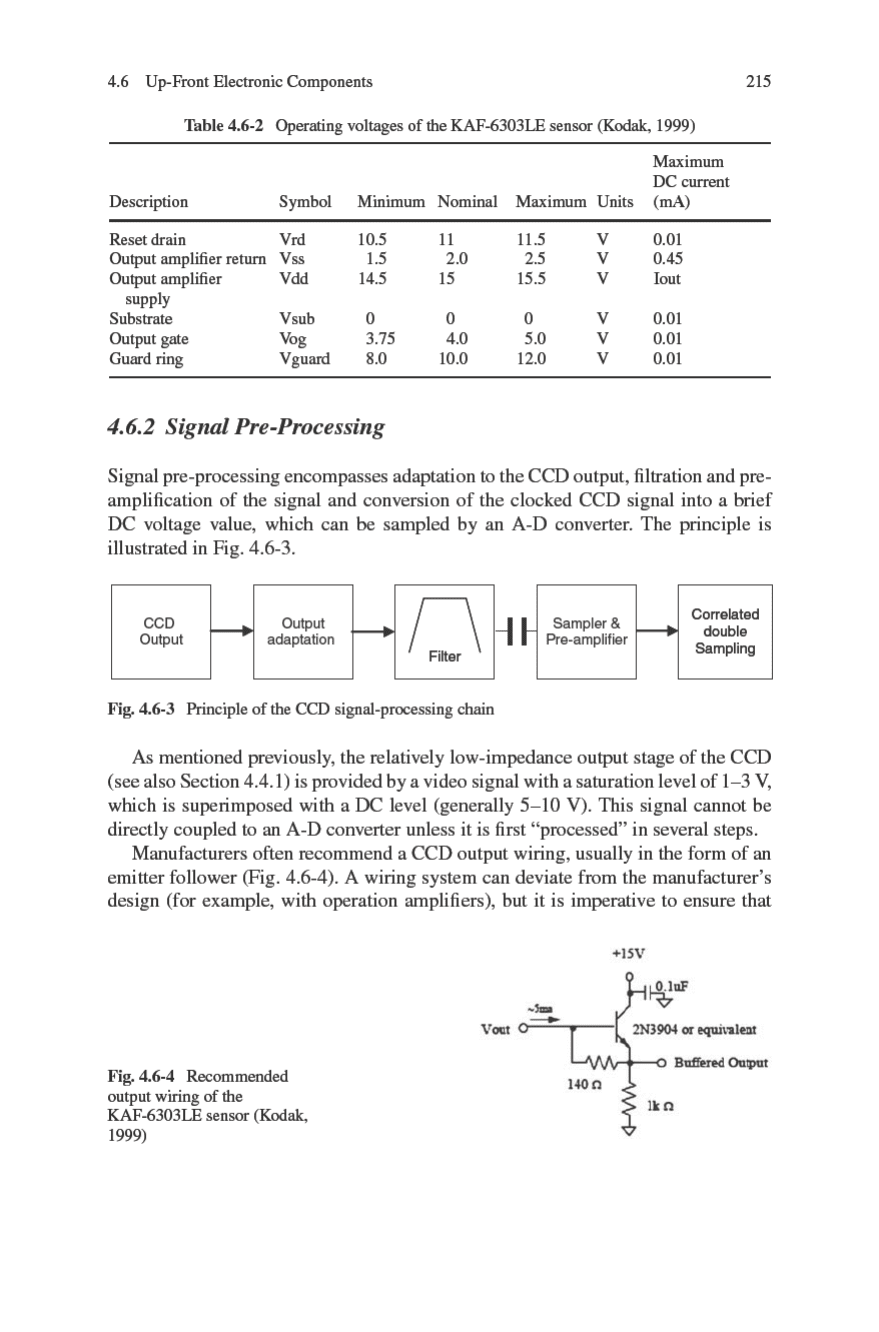

216 4 Structure of a Digital Airborne Camera

the DC operating point and/or the maximum load of the CCD output stage is not

exceeded.

Band-limiting filtration of the signal is advisable in any case before further signal

processing stages in order to eliminate unnecessary noise components as early as

possible.

If a pre-amplifier proves necessary, there should be a DC separation upstream

of it, otherwise the large DC portion is amplified along with the AC or a pure AC

amplification is used. Whether or not clamping is provided downstream of the AC

coupling, for example, at the dark signal pixel level, depends on the subsequent

processing to which the signal is subjected.

The overall quality of the signal processing is decisively influenced by the sam-

pling of the video signal. There are several possibilities here, but correlated double

sampling (CDS) has emerged as the basic principle. This sampling method is based

on the difference between the level of floating diode and the video level of the CCD

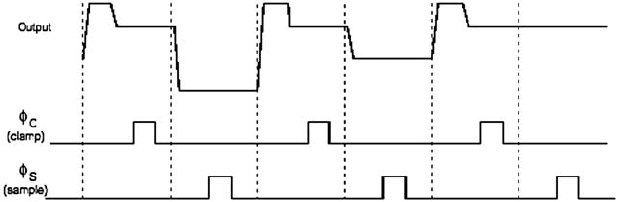

output. The timing of this sampling principle is shown in Fig. 4.6-5. This method has

advantages. Firstly, one obtains the actual absolute value of the signal level without

offset. Secondly, residual noise, i.e., the oscillations of the residual level from one

pixel to the next, is suppressed, since only the current residual level that belongs

to the video level is always used. The reset or floating diode level and the video

level are correlated, hence correlated double sampling. Thirdly, further filtration is

achieved through sampling with narrow sample pulses, which suppresses most of

the low-frequency portions of the 1/f noise. The narrower the sampling pulses φ

C

and φ

S

and the closer they are pushed together, the better the noise suppression.

The two most commonly used CDS methods differ in the following respects:

either (a) after an AC coupling, the clamping of the CCD signal is effected in each

residual level, followed by a sampling of the video level, or (b) both floating diode

and video levels are sampled separately with sample-and-hold circuits and then the

difference signal is formed. In most cases, this difference signal is in turn sampled

by a sample-and-hold circuit to be able to provide the subsequent A-D converter

with the video signal processed in this manner for the entire pixel period.

Special-purpose circuits, which carry out the entire CCD signal-processing oper-

ation, are available from a number of manufacturers. This facilitates the application

considerably. An example is the TH7982A made by Atmel (France), in which not

Fig. 4.6-5 Correlated double sampling principle

4.6 Up-Front Electronic Components 217

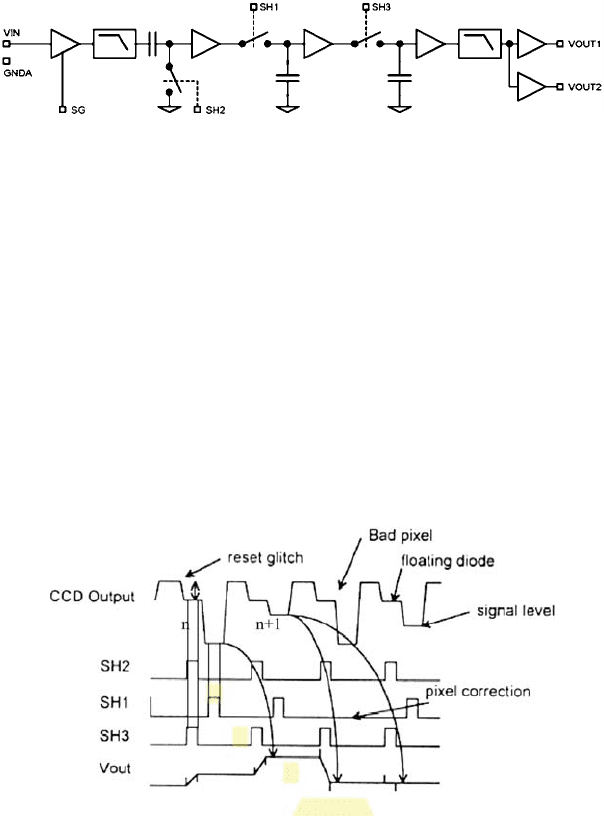

Fig. 4.6-6 Operating principle of the TH7892A CDS circuit (ATMEL, 2001)

only the CDS, but also the pre-amplifier, pixel corrector and the buffer for the A-

D converter are integrated. The operating principle of the TH7982A is shown in

Fig. 4.6-6.

For a better understanding, refer to the timing diagram shown in Fig. 4.6-7. The

actual SH2 (floating diode) and SH1 (signal) CDS pulses are recognisable. For a

kind of pipeline processing, a further sample pulse is added to them, which samples

the difference signal of the pixel n formed by SH2 and SH1 while the floating diode

signal of the pixel n+1is already being captured again by SH2. As an option,

undesired pixels (for example, defects) can be suppressed by a defined fading out

of the SH1 pulse, SH3 then samples the previously stored value again. Two output

buffers of different configuration make it possible to adapt to different A-D converter

types with a signal level of either Vout =±1 V symmetrical to ground or with

standard video level Vout = 1V/50 relative to ground (0 V).

Fig. 4.6-7 Timing diagram of the TH7892A (ATMEL, 2001)

4.6.3 Analogue-Digital Conversion

The charges collected by the CCD are finally converted from the analogue signal

range to a digital signal in the A-D conversion operation. The A-D converter appro-

priate for the application in question can be selected from the extensive range of

commercially available converters. The selection parameters include sampling rate,

resolution, linearity, input storage comparison, design and power drain.

218 4 Structure of a Digital Airborne Camera

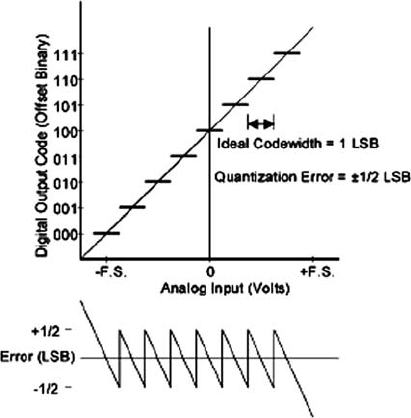

The performance of an A-D converter is primarily restricted by quantization

errors and technology. Some of the ways of assessing the quality of an A-D converter

are briefly discussed. An A-D converter is a quantisizer, which translates analogue

signals into discrete (digital) steps. Each step is represented by a binary value. Since

an A-D converter is a quantisizer, it also exhibits a quantization error. Even an ideal

A-D converter does this, since the digital value represents a certain analogue value

that can deviate slightly from the input signal as soon as an analogue signal has been

converted.

The quantization error is determined by the difference between a linear response

function and the “staircase function” which is characteristic of A-D converters. The

function of the quantization error has the shape of a sawtooth signal and oscillates

between ±0.5 LSB once per LSB (LSB: least significant bit), since the data con-

verter cannot recognise an analogue difference of <1 LSB (see Fig. 4.6-8). The

effective quantization noise Q (rms) = q/

√

12 (q =LSB measure) can be calculated

on the basis of this sawtooth.

An A-D converter’s signal-to-noise ratio is a measured quantity for broadband

noise that is added to the analogue input signal (from the CCD and/or signal process-

ing) during the conversion process. The theoretical SNR of an ideal A-D converter

is calculated as follows:

SNR = U

signal

(rms)/Q(rms)

=(2

n

/2 ·

√

2)(1/

√

12)

=2

n

·

√

3 ·

√

2

= 1.225 · 2

n

.

(4.6-1)

Fig. 4.6-8 Quantization

errors in A-D converters

(Coffey et al., 1999)

4.6 Up-Front Electronic Components 219

Thus

SNR

dB

=20·log (1.225) +n ·log (2)

=1.76+6.02 · n

(4.6-2)

Equation (4.6-2) describes the theoretically attainable signal-to-noise ratio

(SNR) of an ideal A-D converter (quantization noise is the sole noise source of

an n-bit A-D converter). Ideally, U

Signal

relates to a full-scale sinusoidal signal: the

effective value (root mean square) of the sinusoidal signal is obtained by dividing

the peak-to-peak value by 2

√

2.

Hence, based on (4.6-2), an SNR of 86 dB is almost ideal for a 14-bit A-D

converter:

SNR

dB

= 1.76 + 6.02 ·14

or

SNR = 86 dB.

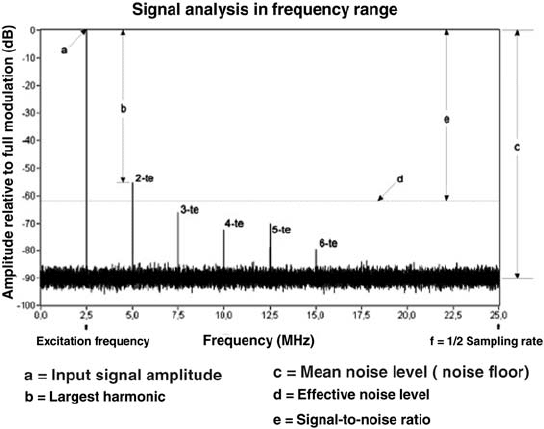

The actual parameters of an A-D converter and its wiring can best be determined

with the aid of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Using this method, all the system

components involved are covered. Instead of the sampled CCD signal, a sinusoidal

signal with extremely low noise and distortions is coupled, the converter is fully

modulated and the FFT is determined on the basis of recorded digital values. The

result is an FFT plot, such as the one shown in Fig. 4.6-9.

Fig. 4.6-9 FFT as a means of determining A-D converter parameters (Datel, 2003)

220 4 Structure of a Digital Airborne Camera

Apart from the signal-to-noise ratio, the FFT analysis provides additional tech-

nical data such as the total distortion factor (linearity) and spurious frequency

spacing, which will not be covered in detail here. The possibility of determining

the resulting number of bits of the actual resolution of the A-D converter is also

interesting.

The SNR value of a system is calculated as a ratio of the effective value of

excitation to the effective value of all noise components. Thus, by analogy with

(4.6-1),

SNR = U

Signal

(rms)/U

Noise

(rms) (4.6-3)

Or, in [dB],

SNR

dB

= 20 · log {U

Signal

(rms)/U

Noise

(rms)} (4.6-4)

The measured data acquisition time (start and end of acquisition), which is also

termed windowing, is limited. This rectangular window function has an effect in the

case of the FFT. The number N of FFT dots yields a correction factor for the y read-

ings. In logarithmic terms this yields the shift 10 ·log(N/2) in the case of windowing.

If the measured data underlying the FFT calculation were acquired asynchronously,

i.e., without a fixed phase and frequency correlation, then the measurement

should be evaluated with another windowing function (for example, Hanning,

Hamming, Blackmann-Harris et al.). In this way the error caused by the phase

position of the periodic sinusoidally shaped excitation relative to the window is

minimised.

Assuming coherent sampling with a rectangular windowing function, we obtain

the following noise floor:

U

Noise

[dB] = effective noise level +10 log(N/2) (4.6-5)

where N = number of FFT dots and N/2 = number of frequency positions.

Another important aspect for evaluating and/or selecting an A-D converter is

the sampling rate. According to the sampling theorem, an original signal can be

unequivocally restored only if the sampling rate fs of the converter is at least twice

as high as the highest frequency fc occurring in the signal, i.e., fs >2fc.

This holds true only, however, if the input signals are assumed to be sinusoidally

shaped. When A-D converters are used for digitising CCD signals, this statement

is compromised, since the input is not a sinusoid, but rather a quasi-discrete signal

which changes its value at equal intervals. It suffices (theoretically) if the converter’s

sampling rate of say 10 Msamples/s is identical to the CCD’s video frequency, in

this case namely 10 Mpixels/s. The basic condition here is, of course, that the A-D

converter has enough time to sample the quasi-stationary value (processed by CDS)

of the video signal. An example of such timing is shown in Fig. 4.6-10. Apart from

the CDS signals SHP and SHD, this timing shows the DATACLK signal. This is the

control pulse for the A-D converter, which is synchronous and staggered in time,

but with the frequency as the CCD video signal. It can be seen from the position

4.7 Digital Computer 221

Fig. 4.6-10 Timing of the AD9824 CCD signal processor (Analog Devices, 2002)

of pixel N that the pixel is processed in a pipeline process of nine steps before it is

available as a digital value at the output of the A-D converter.

Compared to TH7982A, the CCD signal processor AD9824 is a further func-

tional integration stage of analogue CCD processing, which is currently the highest

such stage available. Input MUX dark-signal clamping, CDS, pre-amplifier and an

A-D converter are integrated on a single chip.

4.7 Digital Computer

The generation of digital data and its preliminary processing by calibration val-

ues in the front-end electronics was described in the previous section. This section

deals with digital data processing in the camera and with the control and monitor-

ing of the system as a whole. The key system components and their functions are

reviewed to provide a general overview. Some aspects are then decribed in greater

detail.

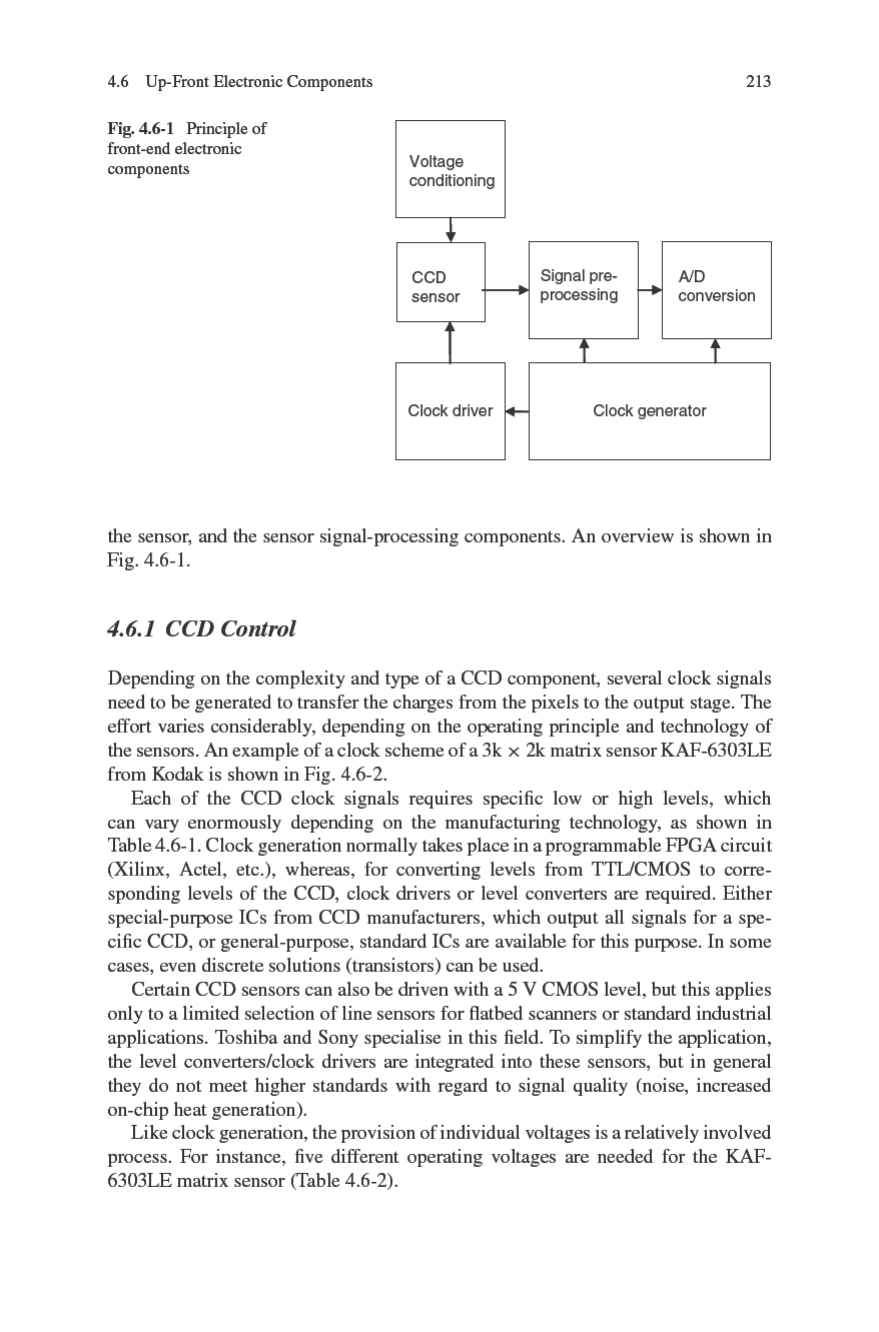

4.7.1 The Control Computer

From the technical point of view a control computer is a PC supplemented

with camera-specific components (Fig. 4.7-1). It is a composite of various func-

tional units controlled, monitored and coordinated by software. It consists of three

functional units:

1. PC with the associated standard components such as graphics board and LAN

2. Image data channel

3. Add-on components such as camera-specific interfaces to external units, cam-

era suspension, GPS/IMU system and modules for monitoring and controlling

ambient conditions.