Pumping Station Desing - Second Edition by Robert L. Sanks, George Tchobahoglous, Garr M. Jones

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

26-4.

Albany

Combined

Sewer

Overflow

Pumping

Station

(CSO

PS 88)

The

combined sewer

overflow

(CSO) project

in

Albany,

Georgia,

is

intended

to

ensure that most storm

water

in the

existing system

is

intercepted

and

con-

veyed

to a new

regional treatment plant. Pumping Sta-

tion

88, one of

several under construction

or

being

upgraded

as a

part

of the

project,

was

nearly ready

for

service

in

October

1997.

The

station

is

designed

for a

maximum capacity

of

227

L/s

(5.2

Mgal/d).

Constant-speed submersible

pumps

are

used. Owing

to an

upstream interception

project,

the

only

flow in an

existing local

750-mm

(30-in.)

sewer

at the

site

is

sanitary wastewater.

The

pumping station will

intercept

wastewater currently

contributing

to an

overloaded interceptor

and

convey

it

through

a

2100-m

(6900-ft)

long force main

to a

new

interceptor.

Static

lift

on the

station

is

only

3 m (10

ft).

Because

of the

long force main, however,

the

total

head

at

peak pumping capacity

is 18 m (60

ft).

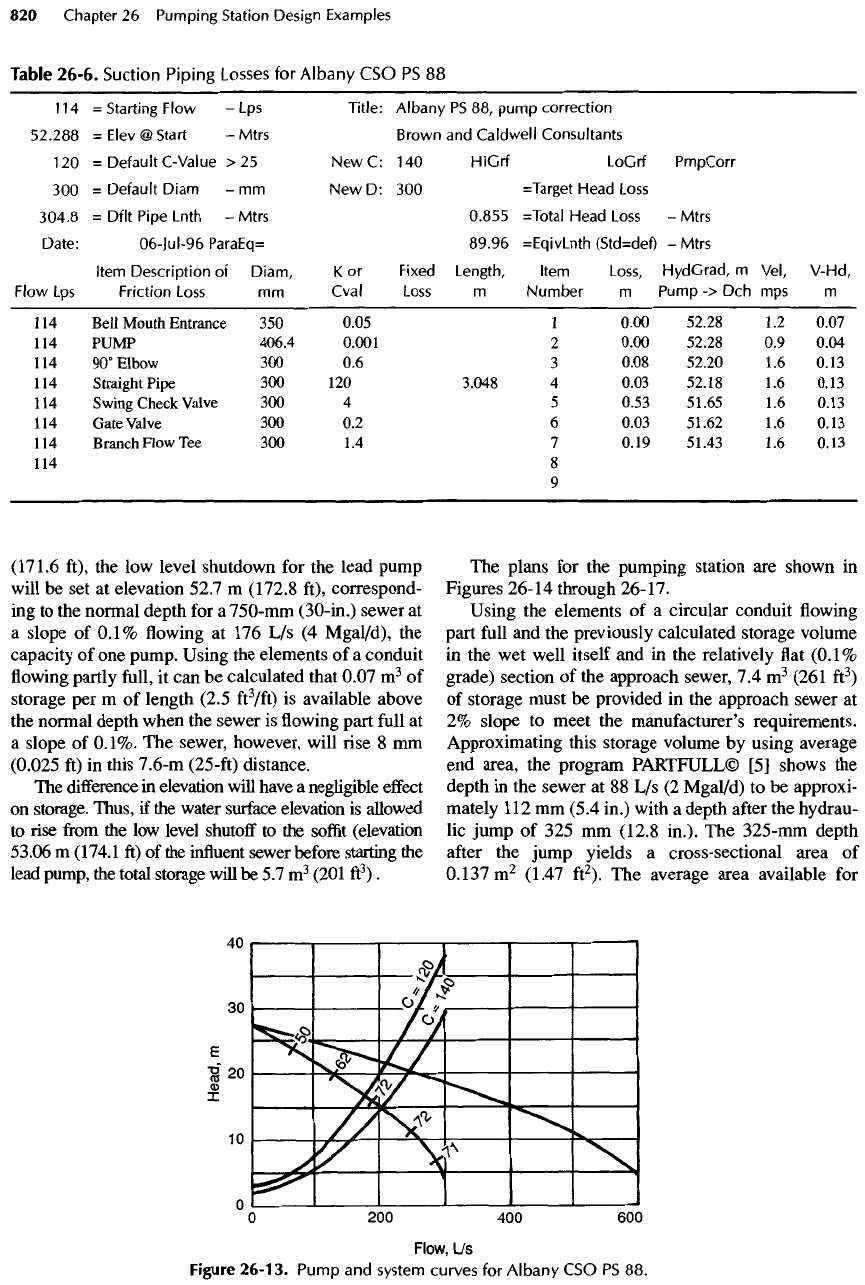

Refer

to

Tables 26-6 through 26-8

and

Figure 26-13

for the

hydraulic

calculations

and

pump selection.

The

existing sewer

was

already

at a

slope consistent

with

a

self-cleaning

wet

well designed

for

constant-

speed pumps

(see

Chapter

12).

The wet

well

and

approach sewer

are

sized

for the

volume required

to

limit

the

pump starting

frequency

to 12

cycles/h

in

accordance with

the

manufacturer's recommendations.

From

the

plans,

the wet

well contains approximately

10.6

m

3

of

storage

for

every meter

of

depth

(1

14

ft

3

/ft).

The

critical

storage

requirement occurs when

a

single

pump

operates alone

and

discharges

175

L/s (4

Mgal/d).

The

volume required

is

given

by

Equation 12-3

V

-

T

*

~

(300

s)

ai75

4

m3/S

=

13.1

m

3

(464ft

3

)

The

station will have

a

7.6-m

(25-ft)

length

of

750-

mm

(30-in.) diameter sewer constructed

at a

slope

of

0.1% upstream

from

the wet

well,

and

then

a new

approach pipe

at 2%

grade will

be

constructed

to

intercept

the

existing sewer (also

at a 2%

grade).

As

more than adequate approach piping

is

available

to

develop

the

storage volume,

the

station pump controls

will

be set to

provide reasonable regulation without

incurring excess storage time, which could lead

to

septic

wastewater

and

corrosion

and

odor

problems.

As

the

above calculation need

not be

precise,

the

use of the

average

end

area formula

for

obtaining

the

needed change

in

liquid level

is

sufficient.

With

the

invert

of the

sewer

at the

station

at

elevation 52.3

m

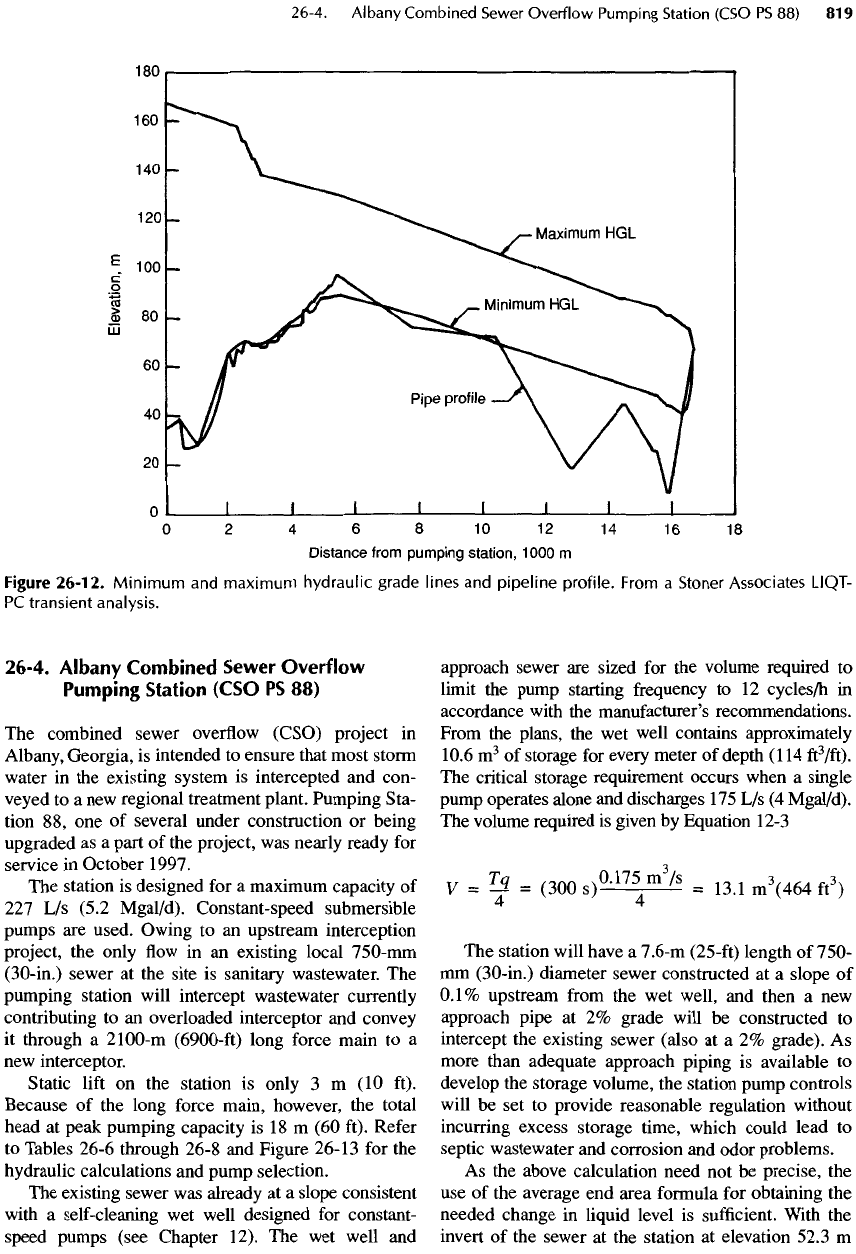

Figure

26-12.

Minimum

and

maximum

hydraulic

grade lines

and

pipeline

profile.

From

a

Stoner Associates LIQT-

PC

transient analysis.

(171.6

ft),

the low

level shutdown

for the

lead pump

will

be set at

elevation 52.7

m

(172.8 ft), correspond-

ing

to the

normal depth

for a

750-mm

(30-in.)

sewer

at

a

slope

of

0.1%

flowing at 176 L/s (4

Mgal/d),

the

capacity

of one

pump. Using

the

elements

of a

conduit

flowing

partly

full,

it can be

calculated that 0.07

m

3

of

storage

per m of

length (2.5

ft

3

/ft)

is

available above

the

normal depth when

the

sewer

is flowing

part

full

at

a

slope

of

0.1%.

The

sewer, however, will

rise

8 mm

(0.025

ft) in

this 7.6-m

(25-ft)

distance.

The

difference

in

elevation will have

a

negligible

effect

on

storage. Thus,

if the

water

surface

elevation

is

allowed

to

rise

from the low

level

shutoff

to the

soffit

(elevation

53.06

m

(174.1

ft) of the

influent

sewer

before

starting

the

lead

pump,

the

total storage will

be 5.7

m

3

(201

ft

3

)

.

The

plans

for the

pumping station

are

shown

in

Figures

26-14

through

26-17.

Using

the

elements

of a

circular conduit

flowing

part

full

and the

previously calculated storage volume

in

the wet

well itself

and in the

relatively

flat

(0.1%

grade) section

of the

approach sewer,

7.4

m

3

(261

ft

3

)

of

storage must

be

provided

in the

approach sewer

at

2%

slope

to

meet

the

manufacturer's requirements.

Approximating this storage volume

by

using average

end

area,

the

program

PARTFULL©

[5]

shows

the

depth

in the

sewer

at 88 L/s (2

Mgal/d)

to be

approxi-

mately

112

mm

(5.4 in.) with

a

depth

after

the

hydrau-

lic

jump

of 325 mm

(12.8

in.).

The

325-mm depth

after

the

jump yields

a

cross-sectional area

of

0.137m

2

(1.47

ft

2

).

The

average area available

for

Table

26-6.

Suction

Piping

Losses

for

Albany

CSO PS 88

114

=

Starting Flow

- Lps

Title:

Albany

PS

88,

pump

correction

52.288

=Elev@

Start

-

Mtrs

Brown

and

Caldwell

Consultants

120

=

Default

C-VaIue

> 25

New

C: 140

HiGrf

LoGrf PmpCorr

300

=

Default

Diam

- mm New D: 300

=Target Head

Loss

304.8

=

DfIt

Pipe Lnth

-

Mtrs 0.855 =Total Head

Loss

-

Mtrs

Date: 06-Jul-96

ParaEq=

89.96 =EqivLnth (Std=def)

-

Mtrs

Item Description

of

Diam,

K or

Fixed

Length,

Item

Loss,

HydGrad,

m

VeI, V-Hd,

Flow

Lps

Friction

Loss

mm

Cval

Loss

m

Number

m

Pump

-> Dch mps m

114

Bell Mouth Entrance

350

0.05

1

0.00 52.28

1.2

0.07

114

PUMP 406.4 0.001

2

0.00 52.28

0.9

0.04

114

9O

0

EIbOW

300 0.6 3

0.08 52.20

1.6

0.13

114

Straight Pipe

300 120

3.048

4

0.03 52.18

1.6

0.13

114

Swing Check

Valve

300 4 5

0.53 51.65

1.6

0.13

114

Gate

Valve

300 0.2 6

0.03 51.62

1.6

0.13

114

Branch Flow

Tee 300 1.4 7

0.19 51.43

1.6

0.13

114

8

9

Figure

26-13.

Pump

and

system curves

for

Albany

CSO PS 88.

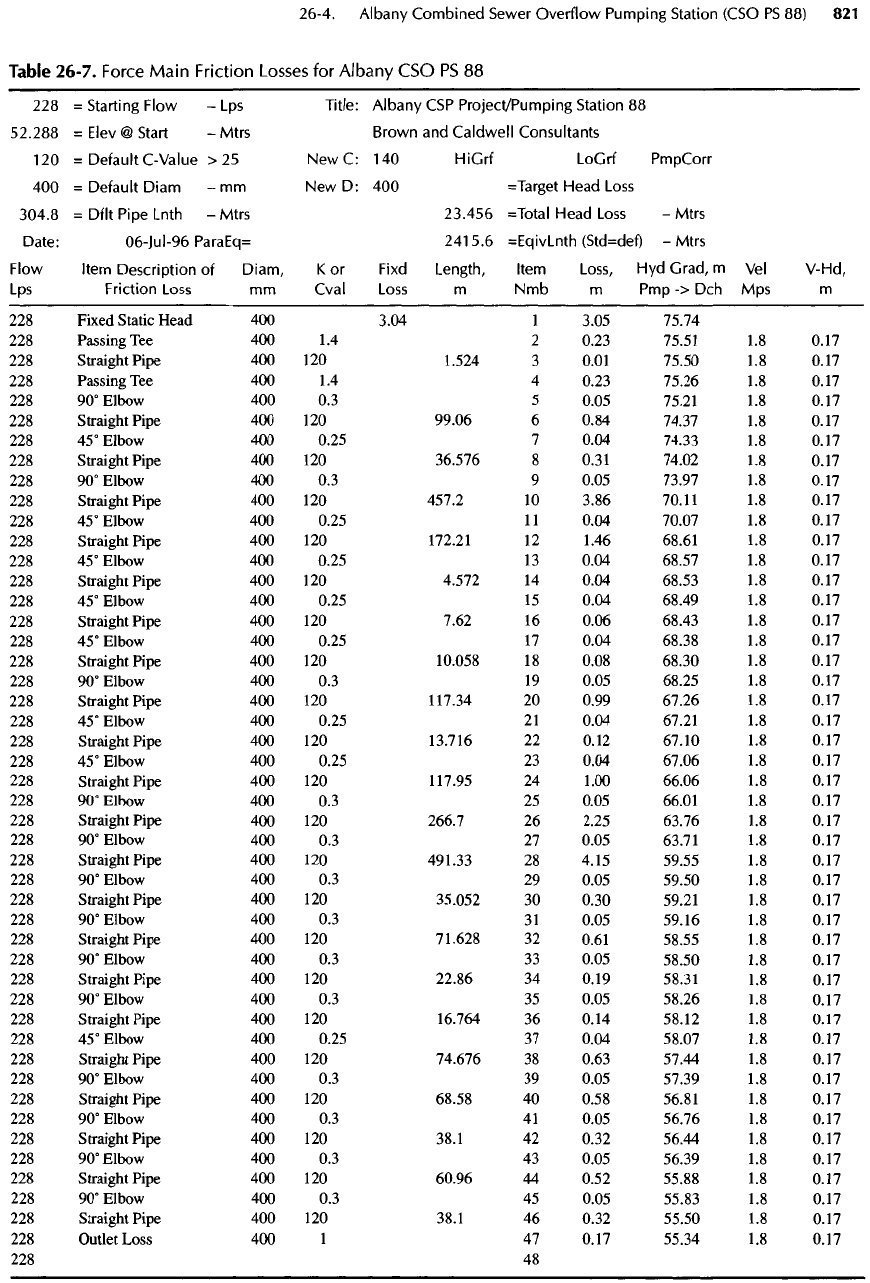

Table

26-7.

Force

Main

Friction

Losses

for

Albany

CSO PS 88

228

=

Starting Flow

- Lps

Title: Albany

CSP

Project/Pumping

Station

88

52.288

=

Elev

@

Start

-

Mtrs Brown

and

Caldwell

Consultants

120

=

Default

C-Value

>

25 New C:

140

HiGrf

LoGrf

PmpCorr

400

=

Default Diam

- mm New D: 400

=Target Head

Loss

304.8

=

DfIt

Pipe Lnth

-

Mtrs 23.456

=Total

Head

Loss

-

Mtrs

Date: 06-Jul-96

ParaEq=

2415.6 =EqivLnth

(Std=def)

-Mtrs

Flow

Item Description

of

Diam,

K or

Fixd

Length,

Item

Loss,

Hyd

Grad,

m VeI

V-Hd,

Lps

Friction

Loss

mm

Cval

Loss

m

Nmb

m

Pmp

-> Dch Mps m

228

Fixed Static Head

400

3.04

1

3.05

75.74

228

Passing

Tee 400 1.4 2

0.23 75.51

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

1.524

3

0.01

75.50

1.8

0.17

228

Passing

Tee 400 1.4 4

0.23

75.26

1.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOw

400 0.3 5

0.05 75.21

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

99.06

6

0.84

74.37

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

7

0.04

74.33

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

36.576

8

0.31

74.02

1.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOw

400 0.3 9

0.05

73.97

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

457.2

10

3.86 70.11

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

11

0.04

70.07

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

172.21

12

1.46 68.61

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

13

0.04

68.57

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

4.572

14

0.04

68.53

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

15

0.04

68.49

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

7.62

16

0.06

68.43

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

17

0.04

68.38

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

10.058

18

0.08

68.30

1.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOw

400 0.3 19

0.05

68.25

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

117.34

20

0.99

67.26

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

21

0.04 67.21

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

13.716

22

0.12 67.10

1.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

23

0.04

67.06

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

117.95

24

1.00

66.06

1.8

0.17

228

90°Elbow

400 0.3 25

0.05 66.01

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

266.7

26

2.25

63.76

1.8

0.17

228

90°Elbow

400 0.3 27

0.05 63.71

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

491.33

28

4.15

59.55

1.8

0.17

228

90°Elbow

400 0.3 29

0.05

59.50

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

35.052

30

0.30

59.21

1.8

0.17

228

90°Elbow

400 0.3 31

0.05 59.16

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

71.628

32

0.61

58.55

1.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOW

400 0.3 33

0.05

58.50

1.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

22.86

34

0.19 58.31

1.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOW

400 0.3 35

0.05

58.26

.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

16.764

36

0.14 58.12

.8

0.17

228

45°Elbow

400

0.25

37

0.04

58.07

.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

74.676

38

0.63

57.44

.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOW

400 0.3 39

0.05

57.39

.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

68.58

40

0.58 56.81

.8

0.17

228

90°Elbow

400 0.3 41

0.05

56.76

.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

38.1

42

0.32

56.44

.8

0.17

228

9O

0

EIbOw

400 0.3 43

0.05

56.39

.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

60.96

44

0.52

55.88

.8

0.17

228

90°Elbow

400 0.3 45

0.05

55.83

.8

0.17

228

Straight Pipe

400 120

38.1

46

0.32

55.50

.8

0.17

228

Outlet Loss

400 1 47

0.17

55.34

.8

0.17

228

48

storage

between

the

downstream

end of the

sewer

(which

is

full)

and the

area above

the

wastewater

at

the

jump,

is,

therefore, (0.46

-

0.19)/2

=

0.14

m

2

(1.45

ft

2

).

An

equation

can be

written

to

solve

for the

required

rise in

liquid level above

the

soffit

of the

sewer

to

obtain

the

required volume

7.4 =

10.6V

+

0.14*

where

y = the rise in wet

well elevation above eleva-

tion

53.1

(soffit

of

sewer

at the

station),

and x = the

length

of

sewer required

to

provide

the

required stor-

age. Because

y =

0.02x,

the

equation

can be

rewritten:

7.4 =

(10.6)(0.02*)

+

0.14jc

=

volume

in wet

well

+

volume

in

sewer

Whence

x = 21 m (70 ft) and y = 0.4 m

(1.3

ft)

The

pump control program

is,

therefore,

as

follows:

Project

elevation,

m

Rising

level

Falling

level

Second

follow

on:

54.6

Second

follow

off:

53.3

High

water

alarm:

54.4

Cancel

high

alarm:

53.2

First

follow

on:

53.8

First

follow off:

53.0

Lead

pump

on:

53.5

Lead

pump off:

52.7

The

pumps must

be

able

to

accelerate

the

liquid

column

downstream

from

the

station each time

the

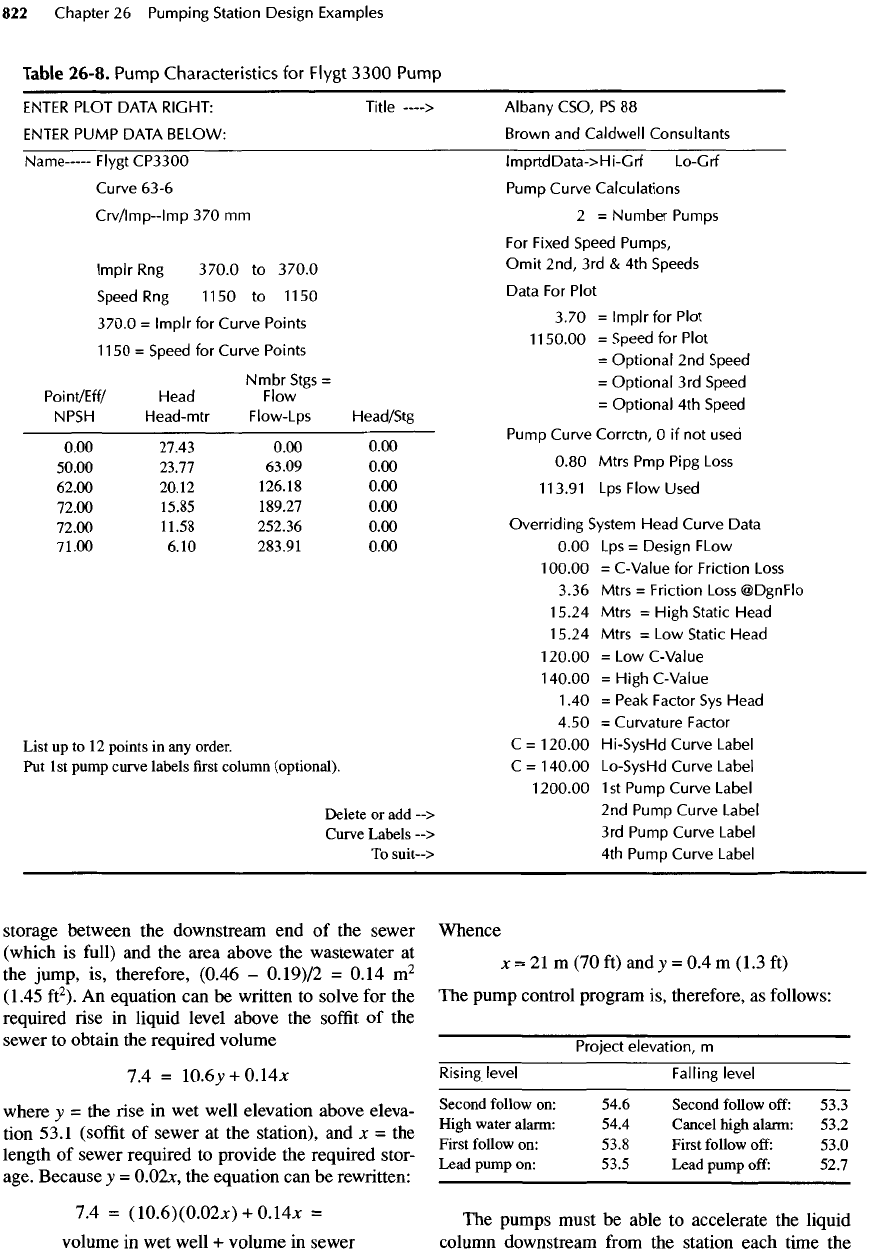

Table

26-8.

Pump

Characteristics

for

Flygt

3300

Pump

ENTER

PLOT DATA RIGHT: Title

—>

Albany

CSO,

PS 88

ENTER

PUMP DATA BELOW: Brown

and

Caldwell

Consultants

Name

Flygt

CP3300

lmprtdData->Hi-Grf

Lo-Grf

Curve

63-6 Pump Curve Calculations

Crv/lmp—Imp

370 mm 2 =

Number

Pumps

For

Fixed Speed Pumps,

ImplrRng 370.0

to

370.0

Omit

2nd,

3rd & 4th

Speeds

Speed

Rng

1150

to

1150

Data

For

Plot

370.0

=

lmplr

for

Curve Points

3

-

70

=

lmplr

for

Plot

1150.00

=

Speed

for

Plot

1150

=

Speed

for

Curve Points

*~

.

.

„

,

„

=

Optional

2nd

Speed

Nmbr

Stgs

=

=

Optional

3rd

Speed

Point/Eff/

Head Flow

=

NPSH

Head-mtr

Flow-Lps

Head/Stg

p

H

Pump

Curve Corrctn,

O if not

used

0.00 27.43

0.00 0.00

H

50.00 23.77 63.09

0.00

°-

80

Mtrs

Pmp

Pipg

Loss

62.00

20.12

126.18

0.00

113.91

Lps

Flow Used

72.00

15.85

189.27

0.00

72.00

11.58

252.36

0.00

Overriding

System

Head Curve Data

71.00

6.10

283.91

0.00 0.00

Lps

=

Design FLow

100.00

=

C-Value

for

Friction

Loss

3.36

Mtrs

=

Friction

Loss

@DgnFlo

15.24

Mtrs

=

High

Static

Head

15.24

Mtrs

= Low

Static Head

120.00

= Low

C-Value

140.00

=HighC-Value

1.40

=

Peak

Factor

Sys

Head

4.50

=

Curvature Factor

List

up to 12

points

in any

order.

C =

120.00

Hi-SysHd Curve Label

Put 1st

pump

curve

labels

first

column

(optional).

C =

140.00

Lo-SysHd Curve Label

1200.00

1 st

Pump Curve Label

Delete

or add -->

2nd

Rum

P

Curve Label

Curve

Labels

--> 3rd

Pump Curve Label

To

suit~>

4th

Pump Curve Label

pumps

start without damage

to the

pump

shaft

seal.

According

to

Krebs [6],

the

formula

for

calculating

acceleration

is:

-

-

•»»'[»:-».]

where

AT

is

acceleration time

in

seconds,

L is

pipeline

length

in

meters

or

feet,

v is

velocity

in the

pipeline

at

full

pump discharge

in m/s or

ft

3

/s,

H

80

is the

pump

shutoff

head

in m or ft, and

H

s

is the

static

lift

on the

system

in m or ft.

From

the

information presented previously,

the

calculated acceleration time

for the

system

is

approxi-

mately

13

s

—

sufficient

to

cause some concern. Candi-

date pump manufacturers were contacted

to

discuss

this

problem

and

determine whether they were willing

to

warranty their products

for

this duty.

If

not,

the

fur-

nished

equipment

may

suffer

from

excessive mainte-

nance

costs associated with premature

failure

of the

shaft

seal.

26-5.

References

1.

Wheeler,

W.

PUMPGRAF©

For a

free

copy

of

this

computer program with instructions, send

a

formatted

1.4

MB,

3

1

J

2

-M.

diskette

and a

stamped self-addressed mailer

to 683

Limekiln Road, Doylestown,

PA

18906-2335.

2.

Hydraulic Institute.

"HI 9.8

Pump Intake

Design."

Hydraulic Institute, Parsippany,

NJ

(1997).

3.

Hydraulic Institute Standards

for

Centrifugal, Rotary

&

Reciprocating

Pumps, 14th

ed.

Hydraulic Institute,

Parsippany,

NJ

(1983).

4.

Stoner Associates.

PO Box 86,

Carlisle,

PA

17013.

5.

Wheeler,

W.

PARTFULL©.

For a

free copy

of

this

computer program with instructions, send

a

formatted

1.4

MB,

3V

2

-Hi-

diskette

and a

stamped self-addressed mailer

to 683

Limekiln Road, Doylestown,

PA

18906-2335.

6.

Krebs,

R.

"Have

you

broken

any

shafts

lately?"

Pumps

and

Systems,

2:18-19

(June

1994).

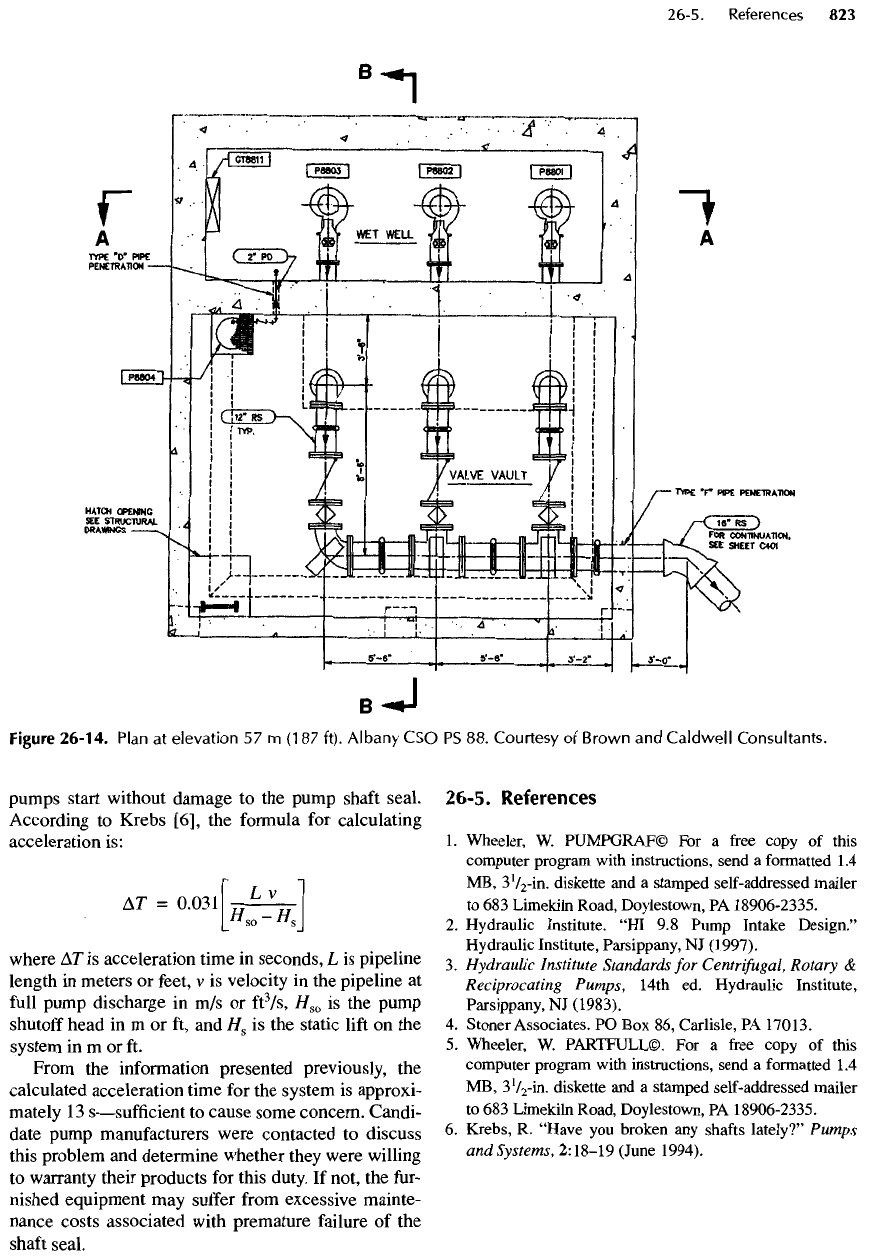

Figure

26-14.

Plan

at

elevation

57

m

(187

ft). Albany

CSO PS 88.

Courtesy

of

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants.

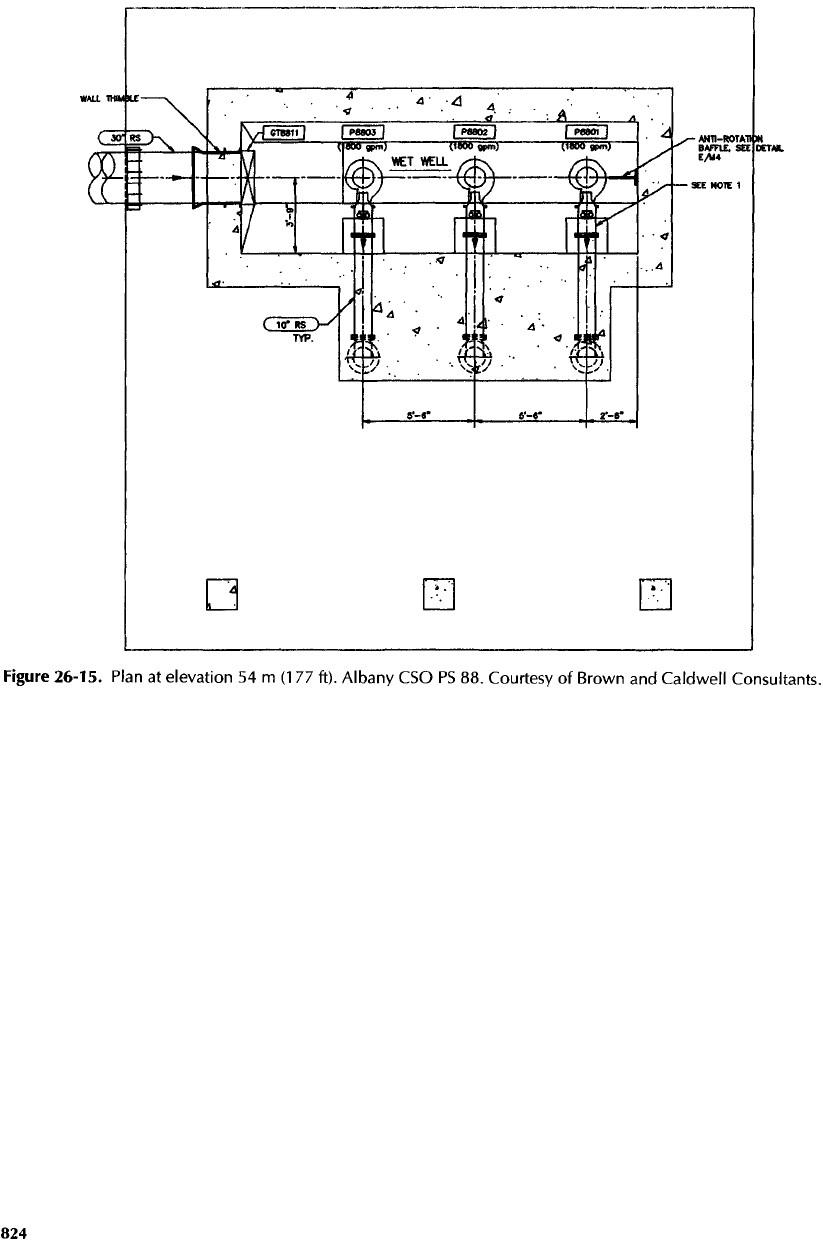

Figure

26-15.

Plan

at

elevation

54 m

(177

ft). Albany

CSO PS 88.

Courtesy

of

Brown

and

Caldwell

Consultants.

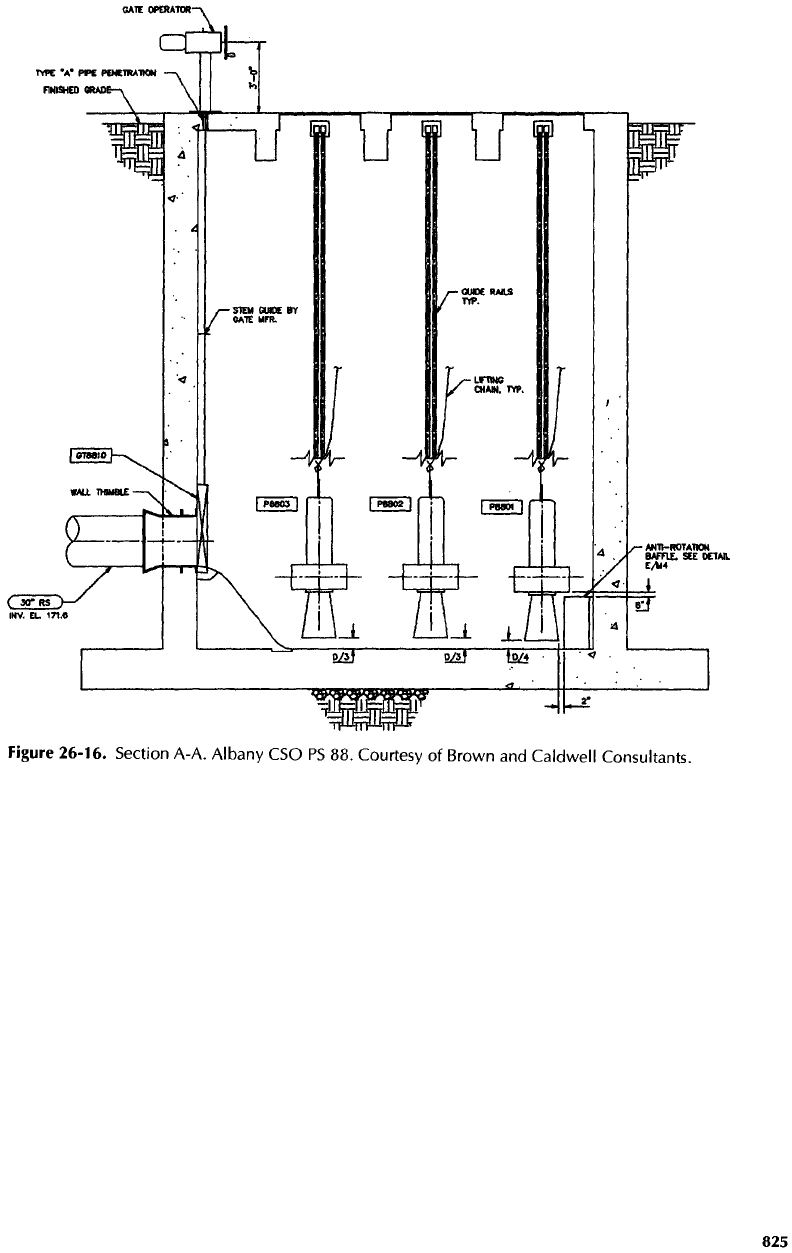

Figure

26-16.

Section A-A. Albany

CSO PS 88.

Courtesy

of

Brown

and

Caldwell

Consultants.

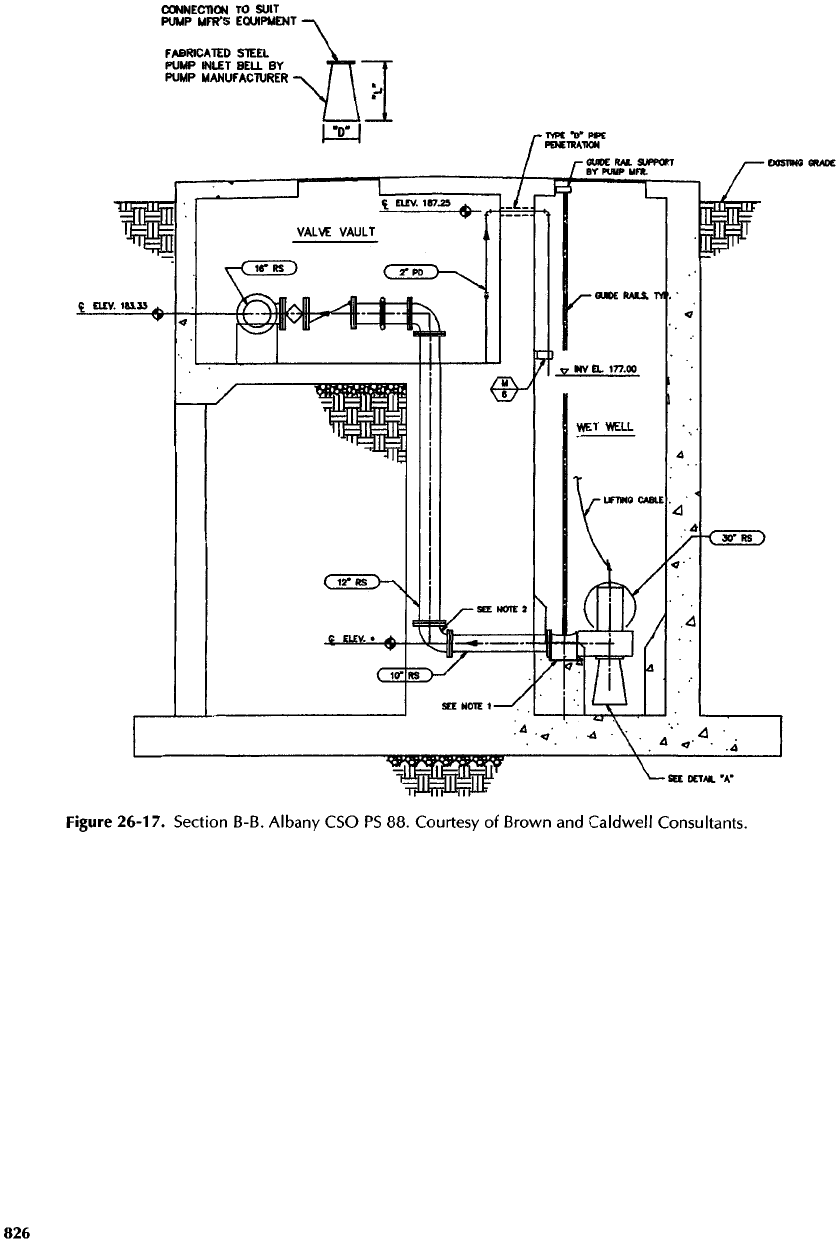

Figure

26-17.

Section B-B. Albany

CSO PS 88.

Courtesy

of

Brown

and

Caldwell

Consultants.

Mistakes

in

pumping station design

are

sometimes

disastrous

and

always costly

and

troublesome. They

can

be

minimized

by (1)

knowing

and

frequently

reviewing

the

most common blunders

so as to

avoid

them;

(2)

making periodic design reviews (see Appen-

dix

G) at

various stages

of

design

—

in-house

if

experi-

enced personnel

are

available but,

if

not,

by

engaging

outside, experienced consultants;

(3)

acquiring exten-

sive

knowledge about

the

manufactured products

and

pumping station design

(by

attending equipment

shows, examining many stations,

and

interviewing

managers

and

operators);

(4)

using

a

good deal

of

common

sense

and

care;

(5)

properly coordinating

the

work

of the

different

disciplines

and

professionals;

(6)

making

knowledgeable inspections during construc-

tion;

and (7)

giving warnings against hazardous opera-

tion

in the O&M

manual.

27-1.

General

Some

of the

most common blunders

and

some

ways

to

avoid

them

are

given

in

this chapter.

The

list

of

blunders

is

abridged, however,

so

read Chapter

24

(especially)

as

well

as

Appendices

G and H for

more completeness.

One of the

commonest

blunders

—

one

that

fits no

particular

category

—

is

failing

to

maintain adequate

written records

of all

significant conversations,

letters,

decisions,

and

calculations that pertain

to the

project

design.

The

records must

be

neat, indexed, complete,

understandable,

and

dated

so

that

any

engineer

can

interpret them;

careful

record keeping

is

desirable

for

others

who may

wish

to

discover

the

secrets

of a

suc-

cessful

design

and a

necessity when personnel

changes

are

made

or

when there

is a

subsequent arbi-

tration

or a

lawsuit.

The

records

should

be

kept neatly

bound

in, for

example,

one or

more three-ring binders.

Another

of the

most common

blunders

—

one

that

seems

to

appear

in

most

or at

least many pumping sta-

tions

—

is

inadequate room

for

heads, hands,

feet,

wrenches,

and

rumps. Much

of the

maintenance

and

repair work requires space

for a

team

of

workers

—

not

just

one

individual.

An

absolute minimum

of

clear

space

free

from

all

protuberances

is

0.92

m

(36

in.),

preferably

on

three sides

of the

machine,

and

l.lm

(42

in.)

is

better.

Chapter

27

Avoiding

Blunders

ROBERT

L.

SANKS

CONTRIBUTORS

William

R.

Kirkpatrick

Marvin

Dan

Schmidt

Stefan

M.

Abelin

Frank

Klein

Earle

C.

Smith

Robert

H.

Brotherton

R.

Russell

Langteau Charles

E.

Sweeney

Fredric

C.

Burton

Jerry

G.

Lilly

LeRoy

R.

Taylor

Patrick

J.

Creegan Ralph

E.

Marquiss

Michael

G.

Thalhamer

Johannes

deWaal Charles

D.

Morris

David

Walrath

James

C.

Dowel

I

Constantine

N.

Papadakis Gary

Z.

Watters

Fred

A.

Fairbanks Carl

W. Reh

Frederick

R. L.

Wise,

Jr.

Philip

A.

Huff

William

H.

Richardson

Many

blunders seem

so

obvious.

It

does

not

even

take

an

engineer

to

avoid them.

It

just takes thought-

fulness

and a

sense

of

responsibility.

It

helps

to

culti-

vate

an

attitude

of

asking,

"How

can

this piece

of

equipment

be

maintained, disassembled,

fixed, and

reassembled,

or

replaced?"

Standard specifications

and

codes

are

identified

only

by

their common abbreviations (see Appendix

E

for

a

complete listing).

27-2. Site

Existing

utilities

and

obstructions

not

shown

on the

plans.

Obtain

utility

company information

for the

spe-

cific

site. Prepare

a

good site plan

and field

check

the

design.

Location

in floodplain

without

adequate protec-

tion. Interview

old

timers about

high-

water

marks,

obtain government

flood-hazard

maps, and,

if

critical,

compute

flood

elevations.

Inadequate

street access

and

parking.

Plan

for

access

and

enough parking space

at the

site (closed

to

public

parking)

for

maintenance vehicles, including,

if

appropriate,

a

crane.

Nonconformity

with setback

and

other planning

and

zoning ordinances. Review

the

regulations before

selecting

the

site.

Site

plan

scale inadequate

to

show

all

details

of

site

work. Normally, choose

a

scale

of 1 in. = 50 ft or

larger.

Wells

located

too

close

to

sanitary

hazards

or

property

lines.

The

site plan should show

the

existing

facilities.

Follow

the

state sanitary codes.

Elevation

of finished

work incorrect. Insist

on

ties

to at

least

two

benchmarks.

Field

check

the

contrac-

tor's

work prior

to

placing concrete

for

critical items.

Ground

floor too low or floors

without slope.

Flooding

or

drainage problems

are

created

and may

violate sanitary codes. Have

a

good site survey

and

site

plan, establish benchmarks, slope

the floors to

drains,

and

follow

the

state sanitary

codes.

27-3.

Environmental

Inadequate

silencers

on

engines.

Specify

an

accept-

able noise level, say,

55 dB, at the lot

line.

Use a

resi-

dential-quality silencer.

Fans

too

noisy.

Use

larger

fans

at

lower speed.

Noisy

machinery located within, say,

1

I

2

km

(

1

I

3

mi)

of

inhabited areas.

The

alternatives

are (1)

relocating

the

pumping station;

(2)

using storage (except

for

sew-

age) instead

of

standby diesel power;

(3)

obtaining

independent, supplementary electrical power

as a

standby

power source;

(4)

using submersible pumps;

or (5)

planning

to

soundproof

the

station

at the

outset

of

the

design. Take ambient noise-level readings

before

construction

for

protection

in

possible

lawsuits.

Sewer inlet with

a

free-fall

to the

water

surface.

A

free-fall

of

sewage into

a wet

well might

(1)

enhance

odors

and (2)

promote foaming

and air

entrainment.

Consider Examples 12-4

and

12-5

for

preventing

ingestion

of air

into pipes, and,

for

both controlling

air

ingestion

and

reducing odors

and

release

of

toxic, cor-

rosive gases, consider

an

approach

pipe

as

shown

in

Figure

12-53.

Odor

production within about

1

I

2

km

(

1

I

3

mi)

of

res-

idential

areas.

The

alternatives

are (1)

relocating

the

pumping station,

(2)

pretreating

the

sewage,

(3)

plan-

ning

for

frequent

housekeeping

by

adding hose valves

(bibbs)

for

washing

out

odor-producing deposits,

(4)

sealing

the wet

well with manhole covers (see

Section

23-1

for

details

and

safety

precautions

for

entry),

or

(5)

adding odor-control facilities

on the wet

well

exhaust.

Odor

control. Near residential areas,

all

vented

air

may

require odor control (see Section 23-2), which

may

well

be the

most expensive part

of

O&M. Always

investigate present

and

future

needs

for

odor-control

facilities

if the

station

is (or

will

be)

near inhabited

areas,

and

design

it so

that odor control

can be

added.

When using odor-control systems such

as

carbon

sorption,

consider thermostatically controlled heating

to

prevent

the

freezing

of

moisture

in the

exhaust.

27-4.

Safety

It

is

poor economy

to

skimp

on

items that have

a

strong potential

for

life-threatening

or

hazardous situ-

ations.

Ventilation

Inadequate

ventilation

system

for wet

well.

For

waste-

water

wet

wells that must

be

entered

frequently,

12

air

changes

per

hour

(ac/h)

is a

minimum

to

meet most

codes.

But 12

ac/h

can be

hazardous,

and an

exchange

rate

of 20

ac/h

is a

more reasonable minimum.

The

California State Department

of

Health recommends

25

and the

Arizona Department

of

Health requires

30

ac/h.

Intermittent ventilation, which

is

allowed

by

some codes, including Ten-State Standards [1],

is

con-

sidered here

to be

entirely inadequate where human

life

is at

stake.

The

scavenging

of wet

wells

is

imper-

fect

at

best,

and the

energy cost saving

is not

worth

the