Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

brian davies

the hetmans it was possible in turn to force the colonels and starshina to accept

Muscovite garrisons as an essentially permanent fact.

Muscovite military power, near exhaustion by the end of the Thirteen Years

War, had revived very quickly and grown to impressive new proportions.

The number of effectives for field army service reached 164,600 men in 1680

(55 per cent of these were in the foreign formation infantry and cavalry).

30

Thousands more performed garrison duty on the Belgorod Line and the new

Iziuma Line. The two Chyhyryn operations, the great defensive deployment

of 1679, and Golitsyn’s Perekop expeditions demonstrated Muscovite ability to

mobiliseandmaintaincampaignarmies of extraordinarysize.

31

Thecampaigns

of the 1670s–1680s also show more authority for command-and-control being

moved out of the Military Chancellery at Moscow and closer to the front. The

Chyhyryn campaigns also show the foreign formation infantry finallyfulfilling

its tactical potential, especially in their 26 August 1677 night descent across the

Sula River and their 3 August 1678 assault on Strel’nikov Hill.

32

During or immediately after the Russo-Turkish war there were a number

of important reforms further addressing the needs of the army. In 1678 the

Military Chancellery issued revised standards for assignment to the traditional

and foreign formation cavalry units in the Belgorod corps, limiting eligibility

for service in these units to those holding a certain minimum number of peas-

ant households, that is to men prosperous enough to maintain themselves in

cavalry service from their pomest’ia alone. This made it possible to eliminate

the need to pay cash allowances to cavalrymen and reassign less prosperous

servicemen from cavalry units to the infantry regiments. Over the next two

years the infantry regiments were further expanded through a drive to enrol

thousands of vagrants, pardoned shirkers, impoverished deti boiarskie and cos-

sacks and musketeers. By 1681 these measures had succeeded in increasing the

relative weight of foreign formation troops in the field army and establishing

a ratio of infantry to cavalry of nearly 2:1.Thestrel’tsy were not abolished but

their units were restructured along the lines of the foreign formation infantry,

reformed into companies under captains and regiments under colonels, so

that they could be put to drilling in foreign formation infantry evolutions. The

centuries of traditional cavalry were likewise reorganised as companies.

33

To raise more revenue for paying the expanded foreign formation infantry

a major reform of state finances was undertaken in 1677–81. A new general

30 Chernov, Vooruzhennye sily,pp.187–9.

31 Stevens, Soldiers on the Steppe,pp.113–16, 120.

32 Davies, ‘The Second Chigirin Campaign’, pp. 108–11.

33 Stevens, Soldiers on the Steppe,pp.77–84.

518

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Muscovy at war and peace

cadastral survey was undertaken; a number of minor direct taxes were amal-

gamated into one army maintenance cash tax (streletskie den’gi, ‘musketeers’

money’); this cash tax, along with the army grain tax, was now assessed by

household (no longer by sokha, i.e. by area and productive capacity of culti-

vated land); and authority over direct taxation was further centralised in the

Grand Treasury to reduce collection costs and facilitate budgeting.

Command-and-control was strengthened in twoways. The razriad principle

of territorial army group command and administration was extended across

the rest of European Russia by creating five new territorial army groups, for

a total of nine, and assigning to them all troops in field army service, either

in traditional or foreign formation units. This had the effect of simplifying

muster procedures (each army group had two or more permanent designated

muster points), devolving more authority for logistics to the territorial level,

and reinforcing the tendency to use army groups as large corps in operations.

The abolition of mestnichestvo in 1682 was in part motivated by the need to

improve command-and-control; thetasksofmodernisingforcestructure(reor-

ganising traditional cavalry and strel’tsy units into companies and regiments)

and mounting more complex operations (by territorial corps, and by multiple

corps together) made itnecessaryto eliminate precedencesuits and discourage

quarrels over precedence honour that might undermine such efforts.

These reforms constituted a foundation for Peter I’s programme of military

modernisation just as the expansion of diplomatic activity paved the way for

Peter’s efforts to make Russia a leading player in the concert of European

nations.

519

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

22

Non-Russian subjects

michael khodarkovsky

From 1598 to 1613 Muscovy experienced the most severe crises known as

the Time of Troubles. Despite the ravages of civil war and foreign inter-

ventions which marked the Time of Troubles, some in the Muscovite

government continued to attend dutifully to their daily routines and obli-

gations. The local voevodas on the frontiers proceeded to govern their forts

and towns and construct new ones. The Foreign Office in Moscow contin-

ued to receive and dispatch envoys to the peoples on the distant frontiers

and churn out reports about them. The pace of Russian colonisation might

have been slowed down but it did not stop. The ascension to the Russian

throne of the Romanov dynasty in 1613 put an end to the Time of Trou-

bles. Russia emerged from the Time of Troubles with a rediscovered sense

of national identity and a newly found confidence in its incessant territorial

expansion.

Throughout the seventeenth century the Russian government expended

great resources and energy on consolidating its hold over annexed territories

and moving into new ones. By the end of the century, Moscow could boast

of enduring success in expanding further east, where the Russians reached

the shores of the Pacific Ocean, and south and south-east, where the newly

built forts and towns pushed the imperial boundaries further into the steppe.

The seventeenth century also marked the beginning of Russia’s expansion in

the west, where Moscow’s acquisition of territories in Ukraine added a new

dimension to the Russian imperial foundation. No longer did Moscow expand

into lands populated by non-Christians: Muslims, animists, and Buddhists. In

its western borderlands, Russia had come to acquire a large population of

Orthodox Christians who were non-Russian. The ever-growing number of

Russia’s subjects now included non-Christians in the east and non-Russians in

the west.

520

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Non-Russian subjects

The steppe

Russia’s steppe frontier remained ambiguous and ill defined. To the extent that

this frontier was defined, it represented a boundary between Russia and those

who were deemed hostile to it. A peace treaty (shert’) prepared in 1604 by the

governmentofficialsfortheruleroftheGreaterNogai Horde,beg Ishterek,gave

aclear indicationofwhereMoscowbelievedits southernfrontiertolie.Ishterek

was expected to have no contacts with the Ottoman sultan, the Crimean khan,

the Persian shah, the Bukharan khan, Tashkent, Urgench, the Kazakh Horde,

the Kumyk shamkhal or the Circassians. In other words, Moscow roughly

delineated its southern boundaries stretching from the Crimea to the North

Caucasus to Central Asia.

1

By the early seventeenth century, Russia’s policies in the steppe, which were

meant to encourage the Nogais’ dependence on Russia and to weaken them

by promoting the factional struggle among their leaders, proved to have the

desired effect. Once a powerful confederation of Turkic nomads, the Nogais’

significance had been greatly reduced by the debilitating internal struggle. In

the early seventeenthcentury, the Nogais of the Greater Horde were no longer

capable of mounting any serious challenge to the Russian state in the south

and instead grew desperately dependent on Russia’s economic and military

aid.

But the stability and relative safety on Russia’s southern frontier was always

short-lived, subject to the rapidly changing situation in the steppe. Continuing

the centuries-old pattern, the steppes of Inner Asia disgorged another power-

ful nomadic confederation which came to replace the Nogais in the Caspian

steppe. The intruders shared with their new neighbours neither the overlap-

ping structures of related Turkic clans nor their Islamic religion. The newly

arrived steppe nomads were a Mongol people and avowed Tibetan Buddhists

guided by the Dalai Lama. Their neighbours called them Kalmyks.

Even early exploratory forays by the Kalmyks used to send the Nogais

fleeing in panic from their formidable foe. Moscow’s attempts to arrest the

movement of the Kalmyks further west and to control the situation in the

steppe proved to be futile. In the first decade of the seventeenth century, most

of the Kalmyks roamed along the Irtysh, Ishim and Tobol’ rivers of south-

western Siberia. In the second decade they had crossed the Iaik River, and by

the early 1630s they reached the vicinity of Astrakhan’, routed the Nogais and

the Russian musketeers dispatched to help them, and occupied the pastures

1 ‘Akty vremeni Lzhedmitriia 1-go (1603–1606), Nogaiskie dela’, ed. N. V. Rozhdestvenskii,

ChOIDR (Moscow, 1845–1918), vol. 264, pt.1 (1918): 105–9, 136, 139–42.

521

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael khodarkovsky

along the Volga. Russia’s inability to protect the Nogais from the Kalmyk raids

led some of the Nogais to join the Kalmyks, while the majority chose to flee

further west towards Azov, seeking the protection of the Ottoman Porte.

The arrival of the Kalmyks in the 1630s had a dramatic impact on the

entire southern region. The decades of Moscow’s careful strategies of weak-

ening, dividing and impoverishing the Nogais and its significant expenditures

to implement such policies, seemed to have been wasted. The Nogais, whom

Moscow considered long pacified, had now joined the Crimean Tatars and

the Lesser Nogai Horde near Azov. Together they launched devastating raids

into Russia’s southern borderlands. Only in the three years of 1632, 1633 and

1637 the Nogais and Crimeans captured and brought to the Crimea more than

10,000 Russian prisoners. The newly colonised southern region with its towns

and peasants urgently needed protection.

The danger of the Nogais and Crimeans breaking through the southern

defences and approaching Moscow was no exaggeration. Theintentions of the

Kalmyks, who came to replace the Nogais in the Caspian steppe, remained

unknown. It is unlikely that Russia’s previous historical experiences in the

steppe left Moscow sanguine about the prospect of peace with the Kalmyks.

Faced with the new and dangerous situation along the southern frontier,

Moscow hastened to conclude a peace treaty with Poland in 1634 and to turn

its attention to the south. Indeed, this time Moscow decided to embark on

a new strategy and to invest unprecedented resources in order to secure the

lands already settled and populated by the Russians and to end the threat of

nomadic invasion once and for all.

In a change from previous policies Moscow decided to play the ‘cossack

card’. The cossacks were the ultimate ‘melting pot’ in early modern Russia.

Among several cossack hosts which Moscow claimed to control, the Don

cossacks were the most powerful. In the seventeenth century, they included a

motley crowd of Russians, new converts, Zaporozhian cossacks, Poles, Lithua-

nians, peasants and various fugitives from justice.

2

Mirroring the lifestyle and

the military organisation of the steppe societies, the cossacks were a perfect

antidote to the nomadic peoples of the steppe. And like many non-Russian

peoples, the cossacks proved to be some of Russia’s most mutinous subjects.

In a shift from the previous policy of restraining the Don cossacks to avoid

provoking the Ottoman Porte, Moscow was now prepared to further arm the

cossacks and encourage their raids. Such raids, however, were to be carefully

2 Grigorii Kotoshikhin, O Rossii v tsarstvovanie Alekseia Mikhailovicha (St Petersburg:

Tipografiia Glavnogo upravleniia udelov, 1906), p. 135.

522

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Non-Russian subjects

calibrated, and the cossacks were instructed to limit their attacks to the Nogais

and Crimeans alone, and not to raid Ottoman possessions, Azov and Kaffa in

particular.

3

To be sure, controlling the cossacks was no easy matter, as the interests

of the government and the cossacks did not always coincide. After all, it was

not the impoverished Nogais that the cossacks were after. Their eyes were set

on the wealthy Ottoman and Crimean towns and villages along the Black Sea

coast. The only obstacles between the cossacks and the promise of rich booty

and numerous captives were the fortifications of Azov, the Ottoman fortress

in the estuary of the Don, which prevented the cossacks from sailing down

the river to the sea.

When in 1636, enticed by the Crimean khan and under continuous pressure

from the Kalmyks and cossacks, the Nogais abandoned the area around Azov

and crossed the Don on the way to the Crimea, the Don cossacks quickly

moved to lay siege to Azov. In June 1637, Azov was in the hands of the tri-

umphant cossacks. In the next five years, taken aback by this unexpected and

undesireddevelopment, Moscow was presented with an unpalatable dilemma:

to support the cossacks and thus enter war with the Ottoman Empire, or to

avoid war by having the cossacks abandon the fortress. After much hesitation

and deliberation, the government chose avoidance over confrontation.

But the cossacks’ degree of independence from Moscow and a history of

their unruliness and participation in popular revolts made the government

suspicious of their true intentions, and, as the Azov affair proved, not unrea-

sonably so. Use of the cossacks along the frontier had to be supplemented by

a more reliable strategy. In 1635, the government undertook a new and bold

initiative; it began the construction of the fortification lines in the south. The

duration of the construction, the expenditures on these extensive fortification

networks, and the utilisation of human and natural resources for this purpose

made the project the single most ambitious and important strategic under-

taking in seventeenth-century Russia. It was to become Moscow’s own Great

Wall to fend off the ‘infidels’ from the southern steppe.

Constructing a fortification line in the southern region was not an entirely

novel idea. Such fortification lines werealready knownin tenth-centuryKievan

Rus’, and more recently, in the middle of the sixteenth century, they had been

constructed just south of the Oka River. By the 1630s numerous forts and towns

emerged far south of Moscow. Still, these proliferating vanguard military out-

posts had to be supplied from the central regions of Russia because agriculture

3 A. A. Novosel’skii, Bor’ba Moskovskogo gosudarstva s tatarami v pervoi polovine XVII veka

(Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1948), pp. 237–8, 296.

523

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael khodarkovsky

remained a dangerous undertaking on the frontier. It was paramount to pro-

vide further security, if a peasant colonisation of the region were to take place.

The fortification lines were to serve exactly that purpose, becoming, in time,

both the primary means of Moscow’s defence against predations and an effec-

tive tool of Russia’s territorial expansion.

In the decade from 1635 to 1646, Moscow moved its frontier defences much

further south, connecting, in one uninterrupteddefenceline, the naturalobsta-

cles, such as rivers and swamps, with man-made fortifications: several rows

of moats, felled trees and palisades studded with advance warning towers and

forts armed with cannon and other firearms. The first such fortification line

(zaseka or zasechnaia cherta), stretching for more than 800 kilometres from the

Akhtyrka River in the west to Tambov in the east, became known as the Belgo-

rodLine. It took the government another decade to extendthe fortificationline

further east, from Tambov to Simbirsk on the Volga. By the mid-seventeenth

century, both the colonists arriving in the southern regions of Russia and the

residents of Kazan’ province found themselves in relative safety behind the

Belgorod and Simbirsk fortification lines.

4

The Kalmyks were seen as the dangerous outsiders whose raids disrupted

the status quo in the region and thus, in addition to Russia, threatened the

interests of other regional powers from the Crimea to the North Caucasus, to

the Central Asian khanates. At first invincible, the Kalmyks suffered a major

debacle in the steppe and mountains of the North Caucasus in 1644.Alarge

Kalmyk contingent was decimated by the combined forces of the Nogais and

Kabardinians with the help of Crimean Tatar and Russian detachments which

provided the crucial fire power. Driven by mutual interests, the Russians and

Crimeans succeeded in pushing the Kalmyks back east of the Iaik River.

A few years later the Kalmyks were back in force. Led by their new chief tay-

ishi, Daichin, the Kalmyks ravaged the Kazan’ and Ufa provinces, routed the

Crimean troops, and demanded the return of the remains of Daichin’s father

4 On the evolution of the fortification lines see A. I. Iakovlev, Zasechnaia cherta Moskovskogo

gosudarstva v XVII veke (Moscow: Tipografiia I. Lisnera, 1916); V. P. Zagorovskii, Belgorod-

skaia cherta (Voronezh: Voronezhskii Gosudarstvennyi Universitet, 1969); A. V. Nikitin,

‘Oboronitel’nye sooruzheniia zasechnoi cherty XVI–XVII vv.’, in Materialy i issledovaniia

po arkheologii SSSR, vol. 44 (1955): 116–213; Novosel’skii, Bor’ba,pp.293–6. For works in

English which discuss the situation and fortifications in the south see Brian Davies, ‘The

Role of the Town Governors in the Defense and Military Colonization of Muscovy’s

Southern Frontier: The Case of Kozlov, 1635–38’, 2 vols., unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Chicago, 1983; Richard Hellie, Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), pp. 174–80; Carol Belkin Stevens, Soldiers

on the Steppe: Army Reform and Social Change in Early Modern Russia (DeKalb: Northern

Illinois University Press, 1995), pp. 19–36.

524

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Non-Russian subjects

and brothers killed in 1644. When a Russian envoy approached Daichin

with demands to confirm the Kalmyks’ allegiance and submit hostages,

Daichin called him a liar for making such grotesque claims. A realisation

that the Kalmyks’ arrival in the Caspian steppe was irreversible prompted the

Russian authorities to drop some of their customary demands and to adopt

a more conciliatory tone. To enlist the Kalmyks as a counterforce to the

Crimeans, Moscow returned the remains of Daichin’s father and brothers,

offered Kalmyks payments and rewards for their military campaigns, and

trade privileges in the frontier towns. In 1654, after Moscow annexed parts of

Ukraine, the rival alliances took shape: Poland and Crimea were facing Russia

and its new ally, the Kalmyks.

Similar to Moscow’s relationship with other nomadic peoples, Russia’s

alliance with the Kalmyks remained precarious. While the written treaties

(shert’) prepared in Moscow and written in Russian were inevitably phrased as

the Kalmyks’ oath of allegiance, they were, in fact, peace treaties with mutual

obligations by both parties to maintain peace, trade and military co-operation.

Insistingthat the Kalmyks werethe subjects ofthe tsar, Moscowobjected to the

Kalmyks’ independent relations with the Crimea, Ottomans or other powers

potentially hostile to Moscow, suspecting, and correctly so, that the Kalmyks’

allegiances could be easily bought and sold. The Kalmyks, however, believed

that Moscow often failed to live up to its commitments when the Russian

officials did not deliver payments, demanded custom duties and bribes, did

not protect Kalmyks from the raids of Russia’s purported subjects, cossacks

and Bashkirs, and above all, converted to Christianity fugitive or captured

Kalmyks.

Throughoutthe seventeenth century, the Kalmyks’ relationship with Russia

continued to alternate between that of a military alliance against the Crimea

and openly hostile acts against Russia. By the end of the century, a more

pragmatic attitude prevailed in Moscow. In July 1697, a Kalmyk khan, Ayuki,

and the high-ranking Russian envoy, the boyar Prince B. A. Golitsyn, signed a

treaty which was strikingly different from the previous ones. This time it was

the Russian side which undertook commitments to assist the Kalmyks, to put a

stop to the Bashkirand cossack raids,not to dictate the boundaries of Kalmyks’

pastures, and neither give refuge, nor convert the runaway Kalmyks.

5

With the Russian conquest of the Ottoman fort of Azov in 1696, the

Kalmyks realised that, for the time being, their fortunes lay with Russia.

5 Michael Khodarkovsky, Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads,

1600–1771 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992), pp. 105–33.

525

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

0 1500 km500 1000

ARCTIC OCEAN

C

a

s

p

i

an

S

e

a

Lake

Baikal

KAZAKHS

CHINA

Irkutsk

Iakutsk

Kazan’

Moscow

L

e

n

a

A

m

u

r

E

n

i

s

e

i

Tobol’sk

Mangazeia

V

o

lg

a

K

a

m

a

N

.

D

v

in

a

Ob

Eniseisk

Ilimsk

Nerchinsk

Albazin

Surgut

Tomsk

Tiumen’

Okhotsk

Kamchatka

Peninsula

P

e

c

h

o

r

a

Territory ceded

to China, 1689

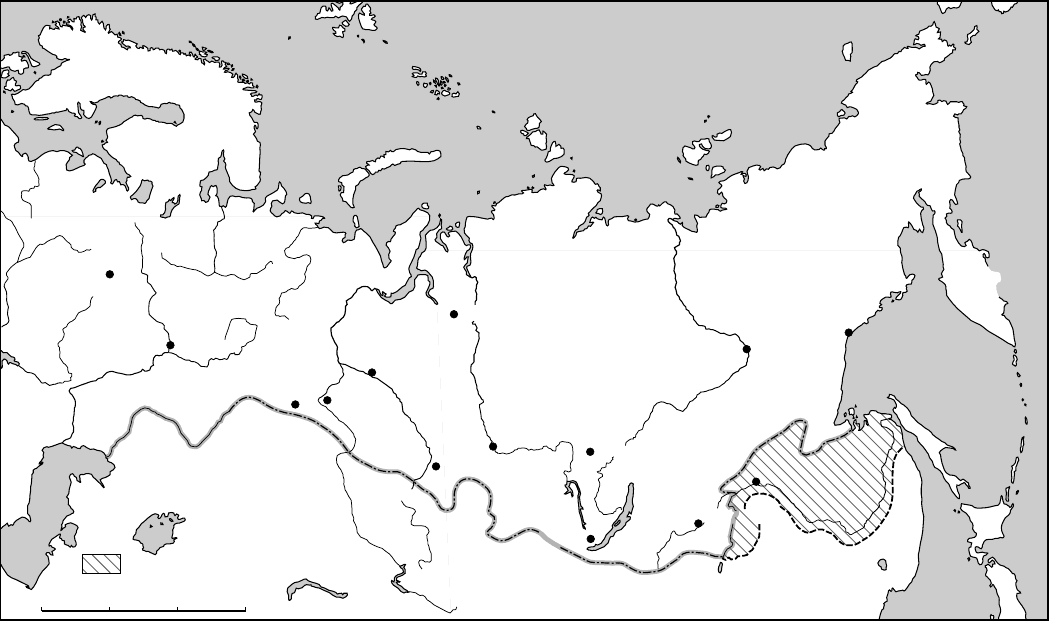

Map 22.1. Russian expansion in Siberia to 1689

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Non-Russian subjects

At the same time, Moscow also concluded that it would gain more by

mollifying the Kalmyks than confronting them. In addressing the Kalmyk

grievances and putting down in writing its own obligations, the govern-

ment was ready to admit that assuring the co-operation of the Kalmyks

and achieving a modicum of peace along the frontier required more than

emphasising the Kalmyks’ submissive status and their obligations. Rather, it

required a clearly articulated recognition that such a relationship was a two-

way street with mutual obligations and commitments. Such an understanding

of their relationship would last for the next two decades, when the newly

confident Russian authorities would once again impose a new set of restric-

tions on the Kalmyks and insist on their explicit submission to the Russian

emperor.

Siberia

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, Moscow was well established

in western Siberia and reached the banks of the Enisei River. Russia’s further

expansion in Siberia skirted a careful line between the northern boundaries of

the steppe and the southern boundaries of the Siberian forest, thus avoiding

the inhospitable terrain of the permafrost wilderness in the north and the

open arid steppe in the south. Russia had to wait for another hundred years

before undertaking an incremental expansion into the steppe lands (presently

northern Kazakhstan), dominated by two powerful nomadic confederations,

the Kazakhs and the Oirats.

In the meantime, the Russians moved south-east reaching the Ili River

where in 1630 they founded Fort Ilimsk. From here, Russia’s first colonists

took two different paths. One route of colonisation took the Russians down

the Lena River into central Siberia, the other moved south down the Ilim river

towards Lake Baikal and the Amur River. In the first instance, the Russians

met little resistance and advanced speedily to the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

In two years, the Russian colonists sailed down the Lena River across the lands

populated by the Evenk (Tungus) and Sakha (Iakut) to found Fort Iakutsk in

1632.In1647, the Russians reached the Pacific coast and founded Fort Okhotsk

in1649.In the second half ofthecentury,Russianforts andsettlements emerged

in the lands populated by the Even (Lamut), Yukagir, Chukchi and Koriak of

north-eastern Siberia. By the end of the century several Russian forts dotted

the landscape of the Kamchatka peninsula (see Map 22.1).

Russia’s expansion along this northern route was no different from other

parts of Siberia wherethe native population could offer sporadic but ultimately

527

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008