Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

brian davies

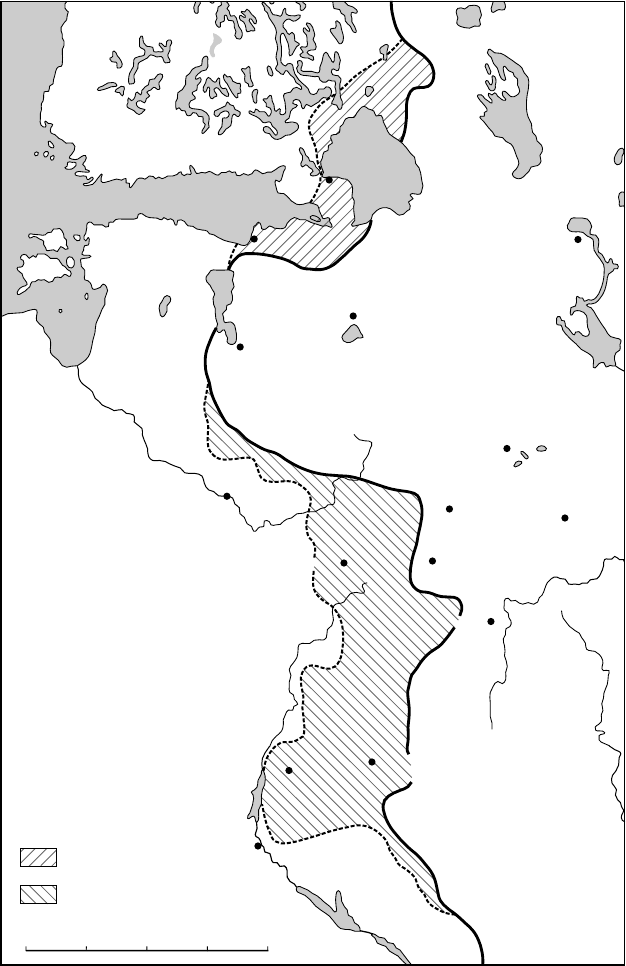

to sue for truce. In December 1618 a fourteen-year armistice was signed at

Deulino. This treaty’s terms were even harsher for Muscovy: the western

Rus’ territories of Smolensk, Chernigov and most of Seversk – holding about

thirty towns in all – were ceded to the Commonwealth, bringing its frontier

as far east as Viaz’ma, Rzhev and Kaluga (Russia’s western borders in 1618 are

shown in Map 21.1). Wl

adyslaw also maintained his claim to the Muscovite

throne.

3

The Stolbovo and Deulino treaties at least bought Muscovy time for recon-

struction and rearmament. Muscovy’s reconstruction occurred in two stages.

In the first stage (1613–18) the boyar duma worked with the Assembly of the

Landto restorebasic order by re-establishingchancellery control over the town

governors, appointing town governors to districts which had not had them

before, suppressing banditry in the provinces, co-opting cossack bands, pres-

suring communities to resubmit to taxation and militia levies and imposing

extraordinary taxes to raise revenue for further reconstruction. The second

phase (1619–30) proceeded under the leadership of the young tsar’s powerful

father Patriarch Filaret (F. N. Romanov), newly returned from nine years’ cap-

tivity in Poland; it devoted further effort to these tasks while also attempting

to repair and improve resource mobilisation for war. Filaret’s administration

gave priority to repopulating state lands and posad communes with taxpayers,

updating cadastres and restoring accounting for arrears and future regular

taxes, issuing commercial privileges to European merchants and restoring

chancellery control over the distribution of service lands and service salaries.

In both stages there were also unsuccessful attempts to secure large loans

from England, the Netherlands, Denmark and Persia in exchange for free

transit trade rights.

Filaret was strongly committed to a revanchist campaign to recover the

western Rus’ territories that had been lost to the Commonwealth during the

Troubles. Regaining control of Smolensk was especially important to him, for

its massive fortress commanded the main road from the frontier to Moscow.

The first few years of his government produced no opportunity to undertake

this, however; reconstruction had to take priority, there was some opposition

to a war of revanche in the Ambassadors’ Chancellery, and Filaret was as

yet unable to get assurance that Sweden and the Ottoman Empire would

join Muscovy in coalition against the Commonwealth. After their defeat at

Chocim (1621) the Ottomans had negotiated a peace with the Poles and were

makingsomeefforttorestraintheCrimeankhan fromraidingCommonwealth

3 Ibid., p. 220.

488

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Muscovy at war and peace

0

400 km

100

200 300

Moscow

Novgorod

Kiev

Lake

Onega

Lake

Ladoga

Polotsk

Pskov

Lake

Chud’

Smolensk

Chernigov

Novgorod

Severskii

Viaz’ma

Rzhev

Kaluga

Tver’

Beloozero

Baltic

Sea

Gulf of

Finland

LIVONIA

Ivangorod

FINLAND

POLAND-

LITHUANIA

Korela

Territory ceded to

Sweden, 1617

Territory ceded to

Poland–Lithuania, 1618

Map 21.1. Russia’s western borders, 1618

489

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

brian davies

territory; Gustav Adolf was interested in alliance with Muscovy, but on terms

of commercial concessions too high for Moscow to pay.

But by the end of the decade opportunity had finally presented itself. Gustav

Adolf’s war against the Poles had ended in an armistice, the Dutch and French

having pressed him to sign a peace at Altmark (1629) so he would carry his

war into northern Germany instead. But to be free to concentrate his forces

in Germany Gustav Adolf now needed a guarantee that the Poles would not

breaktheir armistice and drive his garrisons out of Livonia and Ducal Prussia. A

Muscovite invasion of eastern Lithuania to reconquer Smolensk could provide

the diversion needed to prevent this.

In 1630 Monier, Gustav’s ambassador to Moscow, negotiated a commercial

agreement of great potential benefit to the Swedish campaign in Germany:

Sweden would be given the right to purchase duty-free 50,000 quarters of

Muscovite rye annually, for resale at Amsterdam; given that war had disrupted

the traditional pattern of the Baltic grain trade, this would yield Sweden a

considerable windfall; and in return Sweden would export arms to Muscovy

for its invasion of the Commonwealth. The Monier Agreement paved the way

for an active Swedish–Muscovite alliance. By 1632 this alliance had expanded

into a tentative broader coalition with the Ottomans and Crimean Tatars.

Filaret’s campaign to recover Smolensk thereby became part of a more ambi-

tious coalition war conducted simultaneously on the German, Hungarian and

southern and eastern Commonwealth fronts.

4

In 1630 the Muscovite government began issuing large cash bounties to hire

mercenary officers in Sweden, the Netherlands and Scotland to train a new

foreign formation force (inozemskii stroi) in the new tactics used so effectively

by the armies of the United Provinces and Sweden. Six regiments of infantry

(soldaty), a regiment of heavycavalry pistoleers (reitary), and a regiment of dra-

goons (draguny) were formed from Muscovite peasant militiamen, cossacks,

novitiate middle service class cavalrymen and free volunteers from various

social categories. These regiments would comprise about half the force oper-

ating in the Smolensk theatre in 1632–4. Unlike the traditional formation troops

the new regiments were outfitted and salaried at treasury expense – at very

considerable expense, in fact, the cost of maintaining just 6,610 soldaty in 1633

exceeding 129,000 roubles.

5

Such a heavy investment in units of European type

4 B. F. Porshnev, Muscovy and Sweden in the Thirty Years War, 1630–1635, ed. Paul Dukes and

trans. Brian Pearce (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 28–35.

5 A. V. Chernov, Vooruzhennye sily Russkogo gosudarstva (Moscow: Ministerstvo oborony

SSSR, 1954), pp. 114–15, 157–8; Richard Hellie, Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), pp. 168–72.

490

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Muscovy at war and peace

was necessary, though, because the recent Polish–Swedish war had given the

Commonwealth reason to begin expanding and modernising its own foreign

formation (cudzoziemski autorament).

The death of Sigismund III in April 1632 was followed by an interregnum

whichFilaret thought would last at least several months and provide a window

of opportunity for war to recover Smolensk. Filaret therefore launched an

invasionin August1632, sending M. B.Shein into Lithuania with 29,000 men.By

OctoberSheinhadmanaged to captureovertwentytownsandplaceSmolensk,

his main objective, under siege. But then the Russian offensive stalled. Muddy

roads delayed the arrival of Shein’s heavy artillery. Wl

adyslaw IV finally took

the throne in February 1633 and immediately began assembling an army of

23,000 men to relieve Smolensk. Because Shein’s troops had neglected their

lines of circumvallation Wl

adyslaw’s army was able to surround them and

place the besiegers under siege in August 1633. In January 1634 Shein sued for

armistice in order to evacuate what was left of his army. As Moscow had not

authorised this, and because a scapegoat was needed for the collapse of the

campaign,theboyar dumachargedShein withtreasonandhad him beheaded.

6

Continuing the war against the Commonwealth was unthinkable now. The

war’s chief architect, Patriarch Filaret, had died in October 1633; Gustav Adolf

had fallen at Lutzen in November 1632 and Swedish forces in Pomerania were

now left more vulnerable to a Polish attack; help from the Ottomans could

no longer be expected, for internal revolts and war with Persia had prevented

the sultan from carrying out the invasion of Poland scheduled for spring 1634.

Above all Muscovy again faced a major threat from the Crimean khanate –

not so much from Khan Janibek Girey as from certain Crimean Tatar beys

and mirzas hungry for plunder opportunities after several years of harvest

failure, heavy inflation, and civil war in Crimea. In the spring and summer

of 1632 some 20,000 Tatars ravaged southern Muscovy. In 1633 they came in

even greater strength – over 30,000 strong – and this time circumvented the

fortifications of the Abatis Line and crossed the Oka into central Muscovy,

taking thousands of captives in Serpukhov, Kolomna, Kashira and Riazan’

districts. This invasion may have contributed to Shein’s defeat at Smolensk

by provoking mass desertion by those of his troops whose home districts had

come under Tatar attack.

The Ambassadors’ Chancellery and boyar duma had already decided to

seek armistice in November 1633. But Shein’s capitulation at Smolensk made

6 For accounts of the Smolensk war see E. D. Stashevskii, Smolenskaia voina 1632–1634.

Organizatsiia i sostoianie moskovskoi armii (Kiev, 1919), and William C. Fuller, Jr., Strategy

and Power in Russia, 1600–1914 (New York: Free Press, 1992), pp. 7–14.

491

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

brian davies

it impossible for them to demand that the Poles should evacuate Smolensk

and Dorogobuzh as the price of peace. The armistice signed at Polianovka

on 4 June 1634 therefore left the Smolensk, Chernigov and Seversk lands in

Polish hands. Filaret’s project of recovering the western Rus’ territories had

failed. For Muscovy there was some partial compensation in Wl

adyslaw IV’s

agreement to abandon his claims to the Moscow throne, but it was no longer

realistic for Wl

adyslaw to pursue these claims through war.

The Crimean khanate and the Don cossack host

The peace established by the Polianovka Treaty was undisturbed for two

decades. Resumption of war between the Commonwealth and Muscovy was

deterredbybothsides’recognitionthattheirsimultaneouslyreformed military

establishments had put them at rough parity; and after 1634 Wl

adyslaw IV was

preoccupied with Sweden, cossack unrest in Ukraine, pay arrears in his army

and his magnates’ fears of royal military absolutism.

After the Polianovka Treaty Muscovy could no longer expect active support

from Sweden. The cheap Russian grain exports Gustav Adolf had counted on

to help subsidise Swedish operations had been cut back; Wl

adyslaw IV was

freerto concentratehisforcesagainst Swedishgarrisons on the Balticcoast;and

meanwhile most of Sweden’s allies against the German Empire were suing

for peace with Ferdinand II. Oxenstierna therefore had begun withdrawing

Swedish forces from Germany in anticipation of a Polish or Danish attack

somewhere on the Baltic front. Queen Christina’s other regents were even

more alarmed and made several important concessions, including Swedish

evacuation of Prussia, in order to obtain a truce with the Commonwealth (the

Treaty of Stuhmsdorf, 1635).

This shift in the balance of power in the Baltic made it necessary for Moscow

to disentangle itself from northern European affairs and maintain cautious

neutrality vis-

`

a-vis both Sweden and the Commonwealth. For the most part it

kept to this course, departing from it only briefly, in 1643, when Denmark and

the Commonwealth tried to tempt Muscovy into coalition against Sweden

by holding out the possibility of a marriage between Tsar Michael’s daughter

Irina and the Danish crown prince Waldemar. Entering such a coalition would

have been unwise, for Swedish military power had revived by that point,

strengthened by alliance with France and generous French subsidies. The

tsar and his councillors fortunately realised this just in time, when a Swedish

army under Torstensson invaded and overwhelmed Denmark on the eve of

Waldemar’s arrival in Moscow. The tsar immediately abandoned the marriage

492

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Muscovy at war and peace

project and even placed Waldemar under house arrest to reassure the Swedes

he would no longer listen to Danish blandishments.

As there were no opportunities for territorial expansion or influence on the

Baltic and western Rus’ fronts, Muscovite diplomatic and military activity in

1635–54 focused almost entirely on defending the southern frontier against the

threat from the Crimean khanate.

It was logical and necessary to give the Crimean problem priority because

the khanate was now more dangerous than ever, its behaviour more unpre-

dictable and more resistant to traditional means of containment. The Crimean

Tatar invasions of southern and central Muscovy in 1632–3 showed that the

khan was losing control of his beys and Nogai confederates, that they were

willing to defy him and launch attacks on Muscovite border towns with nearly

as many troops as the khan could mobilise on his own authority. Furthermore,

less could now be expected from Moscow’s traditional diplomatic approach

to deterring Crimean aggression – appealing to the Ottoman sultan to rein in

the khan – for the Crimean nobility was increasingly anti-Ottoman and even

separatist in spirit and the khans under greater pressure to play to this spirit in

order to keep themselves in power.

7

MeanwhileMuscovy had lostmuchofits leverage overits ownvassalpolities

on the Kipchak steppe. It could not count on the fealty of the Great Nogai

beys as a counterweight to the khanate, for the Great Nogai Horde was in

disintegration and many of its elements driven west across the Volga by the

invading Kalmyks and forced into alliance with the Crimean Tatars and Lesser

Nogais. The Don cossack host remained implacably hostile to the khanate and

the Porte, but also ready to defy Moscow whenever their interests diverged; it

had baulked when called upon to support an expedition out of Astrakhan’ to

punish the Lesser Nogais in 1633, and it repeatedly ignored Moscow’s urgings

to cease making naval raids on Crimean and Ottoman territory. Don cossack

raiding activity thereby risked provoking retaliation not only by the Crimean

Tatars but by the Turks. But there was little Moscow could do to prevent

it; reducing the semi-annual cash and stores subsidy (Don shipment, Donskoi

otpusk) sent down the Don just had the effect of giving the host more reason

to turn to raiding to make up its lost revenue. In fact throughout this period

the independent political-military course taken by the host would be nearly

as much a problem for Moscow as the hostility of the Crimean khanate.

7 Mykhailo Hrushevsky, History of Ukraine-Rus’. Vol. viii: The Cossack Age, 1626–1650

(Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 2002), pp. 179–80; A. A. Novosel’skii,

Bor’ba Moskovskogo gosudarstva s tatarami v pervoi polovine XVII veka (Moscow: AN SSSR,

1948), pp. 245–8.

493

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

brian davies

As diplomacy could accomplish little, security on the southern frontier

came to depend all the more on military measures: resuming military coloni-

sation in the forest-steppe and steppe, on a vastly expanded scale and using

new, more cost-effective manpower categories; strengthening and expanding

defence lines; experimenting with new military formations and tactics, and

reorganising command-and-control; and giving greater attention to small-

scale offensive operations, sending small forces down the Don to put more

pressure on the Crimean Tatars while tightening Moscow’s control over the

Don cossack host.

During the Smolensk war the total strength of the Borderland and Riazan’

arrayshadbeenreducedtoabout 5,000 men.Itwasnow substantiallyincreased,

to 12,000 men by 1635 and 17,000 men by 1636. This made it easier for the corps

of the Borderland and Riazan’ arrays to reinforce each other and for the Great

Corps (Bol’shoi polk) finally to begin providing a forward defence, to march

south from Tula to the relief of the towns south of the Abatis Line. The

Military Chancellery also undertook a general inspection of the Abatis Line,

and in 1638–9 it put 20,000 men to work rebuilding some 600 kilometres of

the line. The forces manning the repaired Abatis Line now included foreign

formation infantry and dragoons – some from regiments that had served in the

Smolensk campaign, others newly enlisted – and although their deployment

was only seasonal, this at least set the precedent for using foreign formation

units on the southern frontier against the Tatar enemy.

8

Military colonisation beyond the Abatis Line was resumed in order to estab-

lish an outer perimeter far to the south of the Oka. Several new garrison towns

were built in 1635–7 (Chernavsk, Kozlov, Verkhnii Lomov, Nizhnii Lomov,

Tambov, Userdsk, Iablonov, Efremov), mostly in the south-east, to secure the

territory threatened from the Nogai Road. An earthen steppe wall built from

Kozlov to the Chelnova River proved especially effective in blocking Tatar

raids up the Nogai Road. By early 1637 this had convinced the tsar and duma

to authorise 111,000 roubles to build similar new garrison towns and steppe

wall segments to the south-west, to stop Tatar movement up the Muravskii,

Iziumskii and Kal’miusskii trails. These new towns and steppe wall segments

were built in such proximity that it was an easy matter to link them with

the older steppe town of Belgorod to form a single defence line network, the

central length of the future Belgorod Line.

9

8 A. I. Iakovlev, Zasechnaia cherta Moskovskogo gosudarstva v XVII veke (Moscow: Tipografiia

G. Lissnera i D. Sobko, 1916), pp. 45–6, 57, 62–3.

9 V. P. Zagorovskii, Belgorodskaia cherta (Voronezh: Voronezhskii gosudarstvennyi univer-

sitet, 1969), pp. 93–4.

494

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Muscovy at war and peace

The Military Chancellery wanted to settle these new garrison towns as

rapidly and cheaply as possible, so it took up new methods and formats of

military colonisation. It mobilised thousands of volunteers by relaxing stan-

dards of social eligibility for enlistment in military service, even to the point of

permitting the enlistment of ruined former servicemen who had been forced

by poverty or calamity to take up residence under lords as peasant tenants;

and it altered standards and procedures in court hearings for the remand of

fugitive peasants, to make it harder for lords to recover peasant tenants who

had fled south to enrol illegally in the new garrison towns. Revolt in Common-

wealth Ukraine was driving thousands of Ukrainian refugees into southern

Muscovy; many of them were settled in special new service colonies in the

south-west, on the steppes below Belgorod and Valuiki, in what would come

to be called Sloboda Ukraine, while others were distributed among the new

garrison towns of the Belgorod Line, even as far east as Kozlov. Their cos-

sack experience and their skills at milling, distilling and mouldboard plough

farming would contribute significantly to the success of the Muscovite drive to

colonise the southern steppe. And in a decision very consequential for the sub-

sequent social history of southern Muscovy, the Military Chancellery chose

not to reproduce in the new southern frontier districts the kind of middle

service class – deti boiarskie with service lands of over 200 quarters per field

and peasant tenants – traditionally encountered in central and northern Mus-

covy. Instead it reconfigured the middle service class, adapting it to southern

frontier economic and service conditions, by enrolling deti boiarskie who were

also odnodvortsy and siabry – yeomen with much smaller service land entitle-

ment rates and land allotments, lacking peasant tenant labour and holding

their service lands as repartitionable allotments within collective block grants

administered by their village communes.

These measures strengthening southern frontier defences helped Muscovy

weather the crisis that broke out in spring 1637 when the Don cossacks mur-

dered the Ottoman diplomat Foma Cantacuzene and besieged and captured

the Ottoman fortress of Azov. Azov had been left suddenly vulnerable to a

Don cossack attack because Khan Inaet Girey’s forces were mostly off in Bucak

fighting Khantimur and Sultan Murad IV was preoccupied with wars in Persia

and Hungary. The Don host could justify seizing Azov because its garrison had

provided support for Tatar raids upon Don cossack settlements on the lower

Don, and Ataman Ivan Katorzhnyi may also have calculated that possessing

Azov would allow him to bargain for more generous treatment from the tsar

and larger Don shipment subsidies. But Moscow had no reason to authorise

the seizure of Azov. While Azov’s Ottoman garrison was too small to pose

495

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

brian davies

a threat to the towns of southern Muscovy, its presence had been enough to

serve as a tripwire providing the sultan with cause, if he chose to make use

of it, to retaliate directly against Don cossack or Muscovite aggression. If the

sultan should get the impression that Moscow was in any way complicit in

the attack on Azov it would damage Muscovite trade at Azov and Kaffa and

might even drag Muscovy into war with the Porte.

As long as the Don cossacks occupied Azov (1637–42) Moscow therefore

followed the policy of strengthening its southern frontier defence while simul-

taneously using diplomacy to absolve the tsar of any blame for the crisis. Tsar

Michael sent some grain and munitions to the host but refused their request

to send troops and place Azov under his protection. An Assembly of the Land

convened in 1642 was all for going to war, but Tsar Michael ignored it and

resumedpayingtribute to the newCrimean khan even whileMuscovite envoys

sent to Crimea were being abused. Missions were sent to Sultan Murad IV

and, after his death in 1640, to Sultan Ibrahim, to give reassurance that the

murder of Cantacuzene and seizure of Azov had been the work of brigands

acting ‘for reasons unknown...withoutour instruction’.

10

In June–September

1641 a large Ottoman army commanded by the pasha of Silistria besieged the

cossacks in Azov; although it failed to retake Azov, it clearly demonstrated

how important recovery of Azov was to Sultan Ibrahim, so when Ibrahim

issued a new ultimatum to Moscow in March 1642 Tsar Michael complied and

ordered the Don cossacks to evacuate Azov. Ottoman forces reoccupied Azov

in September 1642 and reinforced its garrison.

War with the Ottoman Empire had been avoided. ThenewTurkishgarrison

at Azov carried out some retaliatory raids on Don cossack settlements but

left the southern Muscovite border towns alone. There had been Crimean

Tatar raids into southern Muscovy in 1637 and 1641–3, but they had been

undertaken by beys and princes acting on their own, driven by famine and

livestock epidemics in Crimea (Inaet Girey’s successors Begadyr Girey, r. 1637–

41, and Mehmed Girey, r. 1641–4, were no more able to curb the Crimean

nobility).

Muscovite–Ottoman relations had suffered serious damage, however. The

Don cossacks had rebuilt their forts and settlements near Azov and were again

attacking Turkish troops; Sultan Ibrahim demanded the tsar remove the host

from the lower Don, a request beyond the tsar’s power to fulfil. The new

Crimean khan Islam Girey III (r. 1644–54) decided the best way to tame the

Crimean nobility was to realign with the Ottoman sultan and put himself

10 S. I. Riabov, Voisko Donskoe i rossiiskoe samoderzhavie (Volgograd: Peremena, 1993), p. 24.

496

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Muscovy at war and peace

at the head of major invasions against the Commonwealth and Muscovy.

Therefore20,000 Tatarsinvaded the Commonwealth and another 20,000 swept

across southern Muscovy in the summer of 1644, carrying off about 10,000

prisoners. Another 6,000 Muscovite captives were taken the following year.

Sultan Ibrahim gave his approval for these operations.

11

By unleashing Islam

Girey III and threatening direct Ottoman military retaliation Ibrahim was able

to stop the Polish–Muscovite rapprochement. In 1646 Wl

adyslaw IV renewed

peace with the Porte and resumed tribute gifts to the khan.

Moscow therefore had to increase investment in its southern frontier

defence system. The Tatar incursions of 1644–5 had taken advantage of partic-

ular weaknesses in that system: the absence of unified command in the corps

of the southern field army, and the over-centralisation of command initia-

tive in the Military Chancellery; the inability of the field army (still stationed

along the Abatis Line) to offer a forward defence for the districts to its south;

large gaps in the Belgorod Line, especially between Voronezh and Kozlov and

between the Tikhaia Sosna and Oskol’ rivers; and Moscow’s inability to stop

Don cossack raids further provoking the Tatars and Turks.

The new government of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich addressed each of these

weaknesses in 1646–54. Several more garrison towns were built and linked up

with the Belgorod Line. Most of the gaps in the line were filled by 1654;by1658

the line extended all along the southern edge of the forest steppe zone, from

Akhtyrka on the Vorskla River to Chelnavsk about 800 kilometres to the east,

and a second defence line some 500 kilometres long extended from Chelnavsk

to the Volga. Twenty-five garrison towns stood on or just behind the Belgorod

Line; thousands of odnodvortsy deti boiarskie, service cossacks and musketeers

had been settled on ploughlands in these new garrison districts.

In 1646 the corps previously deployed far to the north in the Borderland

and Riazan’ arrays were restationed along the new perimeter formed by the

Belgorod Line. The Great Corps, Vanguard and Rear Guard now stood at

Livny, Kursk and Elets each spring and shifted in June to Belgorod, Karpov

and Iablonov. Garrison contingents and small field units south of the Abatis

Line no longer had to march north to rendezvous with the corps but could

move south to join them on the Belgorod Line.

This in turn led to new command-and-control practices along the Belgorod

Line. Because southern garrison forces could now play a larger role in rein-

forcing corps operations, it became necessary for the corps commander at

Belgorod to take up broader year-round operational and logistics authority

11 Hrushevsky, History of Ukraine-Rus’, vol. viii,pp.264–8.

497

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008