Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 5: U-Z

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

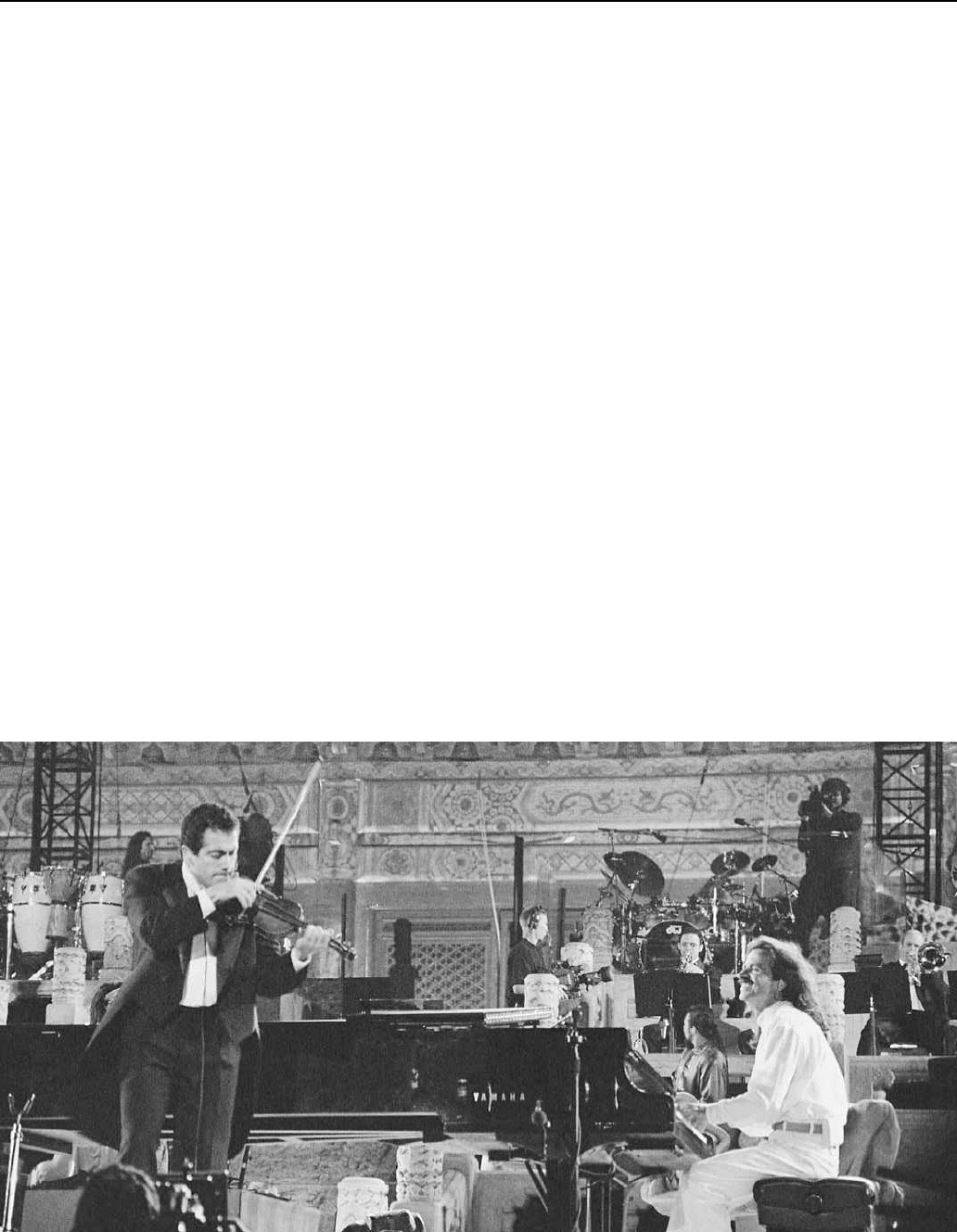

YANNIENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

211

clinical psychology to pursue his creative muse full time. A self-

taught musician, Yanni began composing in his head, relying on

collaborators to put his orchestrations down on paper. He released his

first full-length album, Keys to Imagination, in 1986.

The ‘‘Yanni sound’’ changed very little over the next several

years. Gauzy strains of synthesizer continued to waft insidiously

down upon the listener, as vaguely Mediterranean-sounding hooks

are stated and restated by various instruments. The music incorporat-

ed elements of classical, New Age, and world beat into a sonic

melange that one unfavorable reviewer called ‘‘aural wallpaper.’’

Even Yanni himself often referred to the plastic arts when describing

it. ‘‘Music is like creating an emotional painting,’’ he explained.

‘‘The sounds are colors.’’ Colors derived from an irritatingly narrow

spectrum, according to some critics, who found Yanni’s repetition of

musical themes numbingly aggravating. Despite these brickbats,

however, the Greek tycoon’s record sales climbed throughout the 1980s.

Yanni’s live appearances became major moneymakers as well,

as the mustachioed and classically handsome composer developed a

large and devoted fan following. For concerts, Yanni assembled a

multi-piece orchestra with instrumentation culled from virtually

every continent, over which he would preside beatifically from

behind a stack of keyboards. Yanni often staged his appearances at

major international landmarks, like the Taj Mahal and China’s

Forbidden City. These lavishly mounted productions generated enor-

mous viewership for public television stations across America and

were aired repeatedly during pledge weeks. On one Saturday night in

1994, his concert documentary at Greece’s Acropolis helped one PBS

affiliate raise over $50,000 in pledges. A number of PBS stations even

canceled a previously scheduled Andy Williams special to rebroadcast

Yanni’s performance.

Befitting his superstar status, Yanni cultivated a personal life

designed to keep him in the crosshairs of the paparazzi. In 1989, the

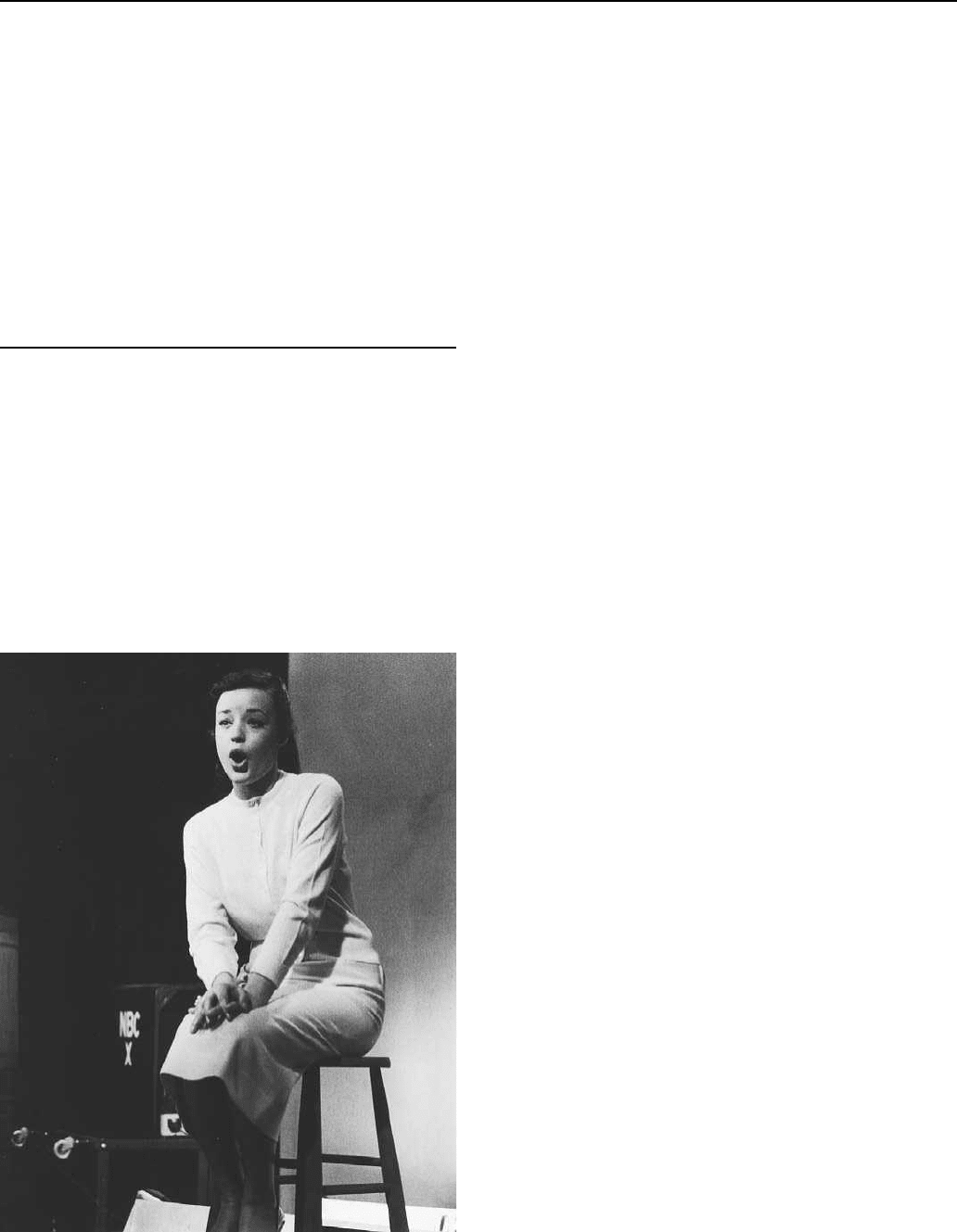

Yanni (seated) in concert in Beijing, China, 1997.

then little-known Yanni began dating Linda Evans, star of TV’s

Dynasty. The flaxen-haired beauty reportedly was won over by the

sinewy Greek’s command of the music of the spheres. They would

remain a couple until 1998, when conflicts over the directions of their

respective careers compelled them to end the relationship.

Indeed, much of Yanni’s success has been attributed to his

appeal to women. But the New Age superstar has bristled at the

suggestion that his cover-of-a-romance-novel appearance drove his

record sales. He claimed the bulk of his fan mail comes not from sex-

starved housewives but from the homebound and the infirm, who find

his music soothing. Some have even ascribed healing powers to

Yanni’s compositions, a claim the composer modestly deflected away.

‘‘I don’t see myself as a peacemaker at all or anything like that,’’

he told the Orange County Register in 1998, ‘‘I’m merely standing in

one place saying it’s possible for us to do this, for people of the world

to share in my music. If I can play even a minute role in something like

that in my lifetime, then I will have accomplished something special.’’

Yanni’s earthly mission continued to draw adherents throughout

the 1990s. In early 1999, he sold out ten dates at New York’s Radio

City Music Hall. Other performers have even followed his path to

success, the critics be damned. The composer and former Entertain-

ment Tonight host John Tesh appeared to have schooled on Yanni’s

PBS-driven marketing plan, replete with extravagantly produced

performances at such notable sites as Red Rocks, Nevada.

—Robert E. Schnakenberg

F

URTHER READING:

Ferguson, Andrew. ‘‘PBS: The Yanni State.’’ National Review.

May 2, 1994.

Wener, Ben. ‘‘Yanni, The World’s Most Loved and Loathed Music

Figure, Is Back.’’ The Orange County Register. March 4, 1998.

YARDBIRDS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

212

The Yardbirds

The backbone of the rock band The Yardbirds consisted of

vocalist Keith Relf, rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja, bassist Paul Samwell-

Smith, and drummer Jim McCarty. However, they were most famous

for their succession of luminary lead guitarists, Eric Clapton, Jeff

Beck, and Jimmy Page. Under Clapton the Yardbirds played high-

energy R&B with long improvisations called ‘‘rave-ups’’ in which

they would alter tempo and volume, building to a climax before

returning to the song. Although the recording technology is poor by

today’s standards, Five Live Yardbirds (1965) reveals a tight unit of

talented musicians. Inspired by the phenomenal success of the Beatles,

the Yardbirds then recorded the pop song, ‘‘For Your Love,’’ written

by Graham Gouldman, and this became their first hit. The song

featured a harpsichord and bongos, but very little Clapton. Uncom-

fortable with the band’s commercial direction, Clapton left to pursue

pure blues in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

Guitar wizard Jeff Beck then joined the band and transformed

the Yardbirds into trailblazing musical pioneers. Innovating with

fuzztone, feedback, and harmonic sustain within the medium of

Gouldman-penned pop songs, they produced classics such as ‘‘Evil

Hearted You’’ and ‘‘Heart Full of Soul.’’ Their first original studio

album, The Yardbirds (1966, renamed Over, Under, Sideways, Down

in the U.S., but commonly known as Roger the Engineer in either

country) is a tour de force on Beck’s part. When Samwell-Smith left

the band, session musician Jimmy Page was recruited as bassist until

Dreja could learn the bass, then Page moved up as second lead

guitarist alongside Beck. The Beck-Page lineup recorded only four

songs, one of them being ‘‘Stroll On’’ (a version of ‘‘Train Kept A-

Rollin’’’), which they performed in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966

film Blow-Up, a cult classic of the Swingin’ London scene.

When Beck left the group, Page introduced his own musical

visions and recorded Little Games (1967). An odd mixture of pop

songs and virtuoso guitar playing, this album is most intriguing as a

document of Page’s early development, displaying many riffs and

effects which were later redeveloped in Led Zeppelin. Especially

noteworthy is the instrumental ‘‘White Summer,’’ later reworked as

‘‘Black Mountain Side’’ and the introduction of ‘‘Over the Hills and

Far Away.’’ When the remaining members left, Page recruited

vocalist Robert Plant, bassist John Paul Jones, and drummer John

Bonham, and debuted the band as the New Yardbirds, later renamed

Led Zeppelin.

In 1984, ex-Yardbirds Samwell-Smith, Dreja, and McCarty

formed the band Box of Frogs (Relf had died in 1976, electrocuted by

a guitar). Although some tracks from Box of Frogs (1984) and

Strange Land (1986) featured guest guitarists Page and Beck, these

heavy-metal offerings made little impact.

The Yardbirds are aptly called ‘‘legendary,’’ for although their

recordings have lapsed into obscurity, their influence on guitar-driven

rock is enduring and pervasive. Clapton, Beck, and Page gave rise to

the ‘‘guitar hero,’’ displacing the singer as the focal point of the rock

and roll band, and a legion of 1970s guitarists cited the Yardbirds as a

major influence. In spite of their uneven recording history, the

Yardbirds’ small, experimental body of work places them just behind

the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who as a major band of the

British Invasion.

—Douglas Cooke

F

URTHER READING:

Mackay, Richard. Yardbirds World. Mackay/Ober, 1989.

Platt, John A. The Yardbirds. London, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1983.

Russo, Greg. Yardbirds: The Ultimate Rave-Up. Floral Park, New

York, Crossfire Publishers, 1997.

Yastrzemski, Carl (1939—)

Better known as ‘‘Yaz,’’ Carl Michael Yastrzemski of the

Boston Red Sox epitomized the spirit of hard work and determination

that made baseball players American heroes in the twentieth century.

As left-fielder, Yaz mastered the art of playing hits off Fenway Park’s

infamous ‘‘Green Monster,’’ earning seven Gold Gloves during the

course of his career. He also was a consistently dangerous batter with

a flair for getting crucial hits in big games. Yaz achieved the coveted

Triple Crown for highest batting average (.326), most runs batted in

(121), and most home runs (44) in 1967 on the way to Boston’s first

pennant in three decades. By the time he retired, he had amassed more

than three thousand hits and four hundred homers, a mark met by no

other player in the American League. He was inducted into the Hall of

Fame in 1989.

—Susan Curtis

F

URTHER READING:

Yastrzemski, Carl, and Al Hirshberg. YAZ: The Autobiography of

Carl Yastrzemski. New York, Viking Press, 1968.

The Yellow Kid

The Yellow Kid by Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928) is

generally held to be the character that gave birth to American comic

strips. The Kid, later named Mickey Dugan by Outcault, was a

smallish figure dressed in a nightshirt who roamed the streets of New

York in company with other urchins. The Yellow Kid was not a comic

strip, rather he appeared as a character in a series of large single panel

color comic illustrations in the New York World with the more or less

continuous running title Hogan’s Alley. The World published the first

of these illustrations, At the Circus in Hogan’s Alley, on May 5, 1895.

The newspaper’s readers, it seems, singled out the Kid as a distinctive

character and his popularity led other artists to create similar charac-

ters. In short succession these actions gave rise to the comic strip.

Outcault was born in Lancaster, Ohio and studied design in

Cincinnati before joining the laboratories of Thomas Edison as an

illustrator in 1888. By 1890 Outcault combined employment as an

illustrator on the Electrical World, a trade journal, with freelance

cartoon work for illustrated humor journals such as Puck, Judge, Life,

and Truth. The Kid’s genesis lay in the genre of city urchin cartoons

made popular by these journals. In particular Outcault drew inspira-

tion from Michael Angelo Woolf’s work.

A prototype Yellow Kid appeared in Outcault’s ‘‘Feudal Pride

in Hogan’s Alley’’ published in Truth June 2, 1894. This small figure

in a nightshirt cropped up in several other Outcault cartoons before

blossoming into a larger more familiar, but as yet unnamed, Kid in

Outcault’s ‘‘Fourth Ward Brownies’’ published in Truth February 9,

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

213

1895 and reprinted in the World February 17, 1895. The Kid appeared

again in Outcault’s ‘‘The Fate of the Glutton’’ in the World March 10,

1895. In these two appearances the Kid’s nightshirt had an ink

smudged handprint a distinctive feature of the later World panels.

After the May 5 episode the World published ten more ‘‘Hogan’s

Alley’’ panels in 1895. The Kid appeared in them all. On January 5,

1896 the Kid was center stage in a yellow nightshirt and thereafter

became the focus of each panel.

The Yellow Kid became the mainstay of the World’s comic

supplement during 1896, but in mid October Outcault moved his strip

from the World to William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal.

Hearst had infamously bought the talent of the World to staff the

Journal and naturally enough poached Outcault for the launch of the

comic supplement on October 18, 1896. Thereafter the Kid appeared

in tabloid page size illustration under the running title ‘‘McFadden’s

Row of Flats’’ before departing on a world tour in 1897. Beginning

October 25, 1896 the Kid also began to appear in an occasional comic

strip like series of panels under the running title of ‘‘The Yellow

Kid,’’ which was Outcault’s first use of that name in a comic

supplement. Outcault stayed with Hearst’s Journal for a little over a

year. The last Yellow Kid comic feature appeared in the Journal

January 23, 1898. Outcault then returned to the World, producing a

series of ‘‘Hogan’s Alley’’–like panels featuring an African-Ameri-

can character.

Outcault’s shift of the Yellow Kid from the World to the Journal

raised issues of copyright. The World continued to publish a version

of the Kid drawn by George Luks. Prior to leaving the World Outcault

had sought copyright protection for his creation in a letter to the

Library of Congress on September 7, 1896. He had also attached the

label ‘‘Do Not Be Deceived None Genuine Without This Signature’’

above his signature in the World’s September 6, 1896 episode of

‘‘Hogan’s Alley.’’ Later advice from W. B. Howell of the Treasury

Department, which policed copyright laws at that time, advised

Outcault that he had failed to secure protection on the image of the

Kid because he had only included one illustration instead of two in his

application. Outcault did however secure protection for the title ‘‘The

Yellow Kid.’’

Two minor controversies have marked the history of the Yellow

Kid. Until the late 1980s accounts of the origins of comic strips

generally accepted that the Yellow Kid’s nightshirt was colored

yellow as a test of the ability of yellow ink to bond to newsprint. But

Richard Marschall argues in his America’s Great Comic Strip Artists

that this could not have been the case since yellow ink had been used

earlier. Likewise Bill Blackbeard gives a detailed account of the

World’s use of color in his introduction to The Yellow Kid: A

Centennial Celebration that makes clear the testing yellow ink theory

is incorrect. The Yellow Kid is often cited as the origin of the term

‘‘yellow journalism.’’ However, the historian Mark D. Winchester

has demonstrated that the term yellow journalism came into use

during the Spanish-American War in 1898 to describe the war

hysteria whipped up by Hearst and Pulitzer. The Yellow Kid was

transformed into a symbol of yellow journalism during this campaign

rather than giving his name to it. The distinction is subtle but crucial.

—Ian Gordon

F

URTHER READING:

Blackbeard, Bill and Martin Williams. The Smithsonian Collection of

Newspaper Comics. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1977.

Gordon, Ian. Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 1890-1945. Wash-

ington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Harvey, Robert. The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History.

Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Howell, W. B., ‘‘Assistant Secretary, Treasury Department to W.Y.

Connor, New York Journal, April 15, 1897,’’ reprinted in, Deci-

sions of the United States Courts Involving Copyright and Literary

Property, 1789-1909. Bulletin 15, Washington, D.C., Library of

Congress, 1980, 3187-3188.

Marschall, Richard. America’s Great Comic Strip Artists. New York,

Abbeville Press, 1989.

Outcault, Richard. The Yellow Kid: A Centennial Celebration of the

Kid Who Started the Comics. Northampton, Massachusetts, Kitch-

en Sink Press, 1995.

Winchester, Mark D. ‘‘Hully Gee, It’s a War!!! The Yellow Kid and

the Coining of ‘Yellow Journalism.’’’ Inks, Vol. 2, No. 3,

1995, 22-37.

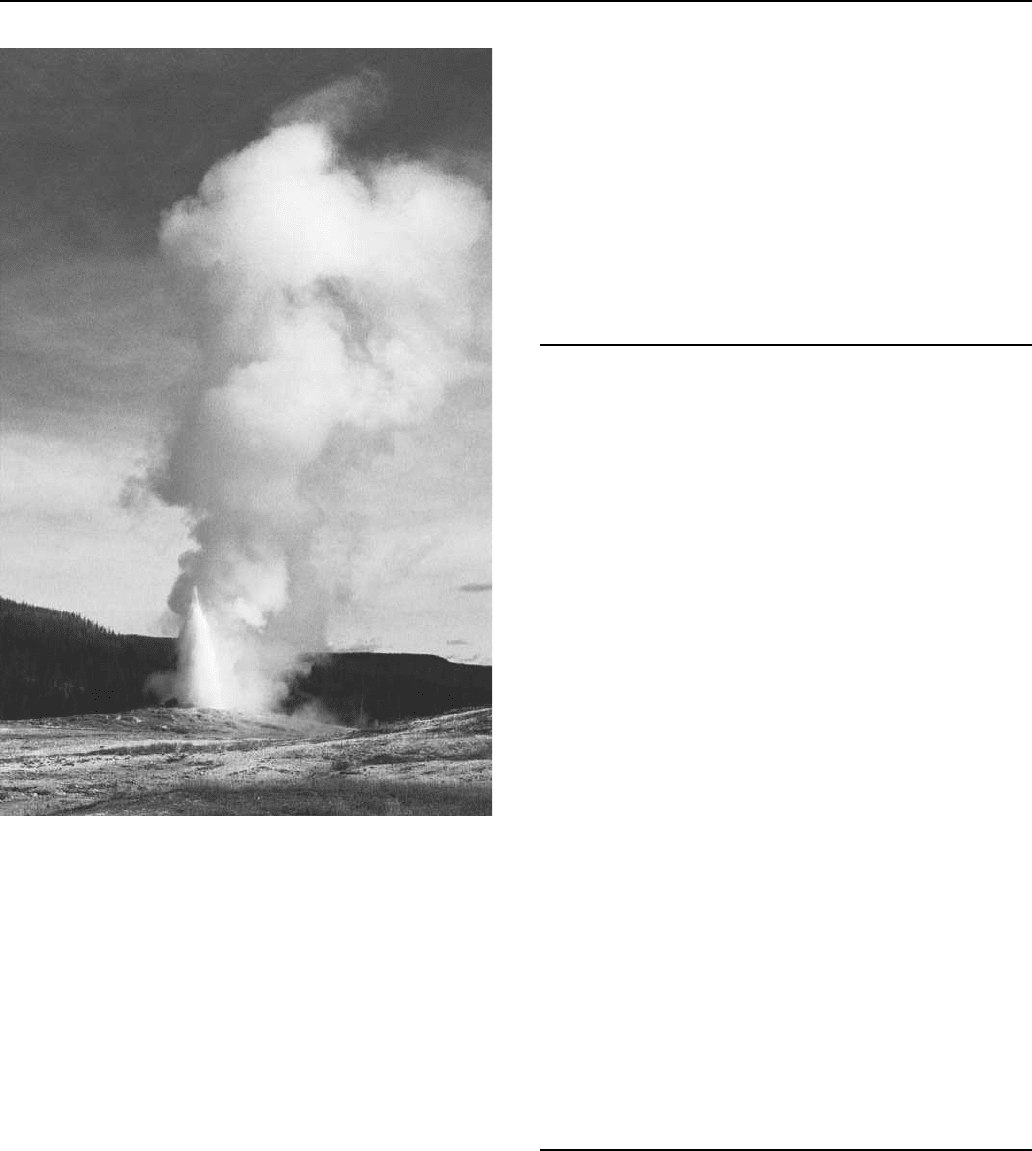

Yellowstone National Park

Comprising 2.2 million acres of northwest Wyoming, with slight

incursions into Montana and Idaho, Yellowstone is the oldest national

park in the United States. The park’s unique sights originally inspired

a nation that had not even fully conceived of what the term ‘‘national

park’’ entailed. The park has evolved to stand as the preeminent

symbol of the national park idea, whether inspiring the designation of

other locations or revealing systematic flaws. Today, Yellowstone

serves as an active battleground as Americans strive to define the

meaning of preservation and wilderness.

From the outset, Yellowstone’s unique attraction derived from

its natural oddities. The region was the stuff of rumors; the return of

explorers from the northern Rockies in 1810 had piqued the public’s

attention with stories of odd natural occurrences: thermal phenomena,

a beautiful mountain lake, and a magnificent canyon entered into the

unconfirmed reports. ‘‘Could such a place exist?’’ Americans asked

upon hearing descriptions of ‘‘Earth’s bubbling cauldron.’’ In 1870,

other expeditions set out to explore the sights. In 1871 the Hayden

Survey explored Yellowstone. Overwhelmed by the majesty and

oddity that they beheld, they were at once overcome by its attraction

and potential development. Such economic development, though,

could exploit and ruin all that made the site peculiar. During this era of

development and the massive harvesting of natural resources, these

attributes were not sufficient to warrant preservation; the site also

needed to be of no worth otherwise. Hayden repeatedly assured

Congress that the entire area was worthless for anything but tourism.

Lurking behind such plans were railroad companies eager to find

tourist attractions in the West.

The establishment of the park by President Ulysses S. Grant

on March 1, 1872, rings hollow by the standards of modern

environmentalism. However, such designation, albeit under the juris-

diction of the U.S. Army until 1916, kept the area free of development

during some of the region’s boom years. As an example, Yellowstone’s

herd of North American bison is given credit for the species’

endurance. While hunters decimated the larger herd by 1880, the park

offered sanctuary to at least a few bison. Today, the Yellowstone herd

is considered an anchor for the entire species. The present herd,

ironically, has also led to controversy as it creeps past park borders.

YES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

214

The geyser named Old Faithful in the Yellowstone National Park.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park

Act, creating the National Park Service and initiating the search for

the meaning of such designation. Tourism rose steadily through the

war years, and Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather largely

developed and linked the park system. With the Wilderness Act of

1964, the shared cause of the park system became the effort to

preserve areas as unspoiled ‘‘wilderness.’’ While it had originally

been set aside due to geological oddities, Yellowstone became a

primary illustration of one of the most unique and secure ecosystems

in the United States.

Yellowstone has proven to be an attraction of enduring propor-

tions. Tourist visitation to the park has increased throughout the

twentieth century, with the park becoming an international attraction.

Massive visitation rates, however, have taken a toll on the remaining

wilderness within the park. Many environmentalists call over-visita-

tion Yellowstone’s major threat. In addition, fires have repeatedly

torn through the park, forcing administrators to consistently revisit

their mandate. Proponents of wilderness argue that naturally occur-

ring fires must be allowed to burn, whether or not they endanger

tourists or damage park service property; administrators who see their

responsibility to visitors argue for fire suppression. Such issues force

Americans to consider what a national park seeks to accomplish and

reidentify Yellowstone’s position as the symbolic leader of the

American system of national parks.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Runte, Alfred. National Parks: The American Experience. Lincoln,

University of Nebraska Press, 1987.

Yes

Yes’s combination of technical proficiency, enigmatic lyrics,

and large egos captured the essence of the progressive rock move-

ment. Formed in 1968, the British art-rock band achieved internation-

al success with The Yes Album in 1971. Further success came with

Fragile (1972) and its hit single ‘‘Roundabout,’’ and Close to the

Edge (1972), which is considered by many to be the band’s masterpiece.

The band excelled in live shows and is known for its long-

jamming songs, some of which are more than twenty minutes long.

Lavish crystalline stage sets designed by artist Roger Dean (who also

drew the band’s album covers) helped make for hugely successful live

shows; in the late 1970s, Yes set a record for selling out New York’s

Madison Square Garden 16 times. In 1983 Yes released 90125 which

became their biggest selling album, carried by their only American

number one hit ‘‘Owner of a Lonely Heart.’’

Even though the members of the band have changed incessantly

over the years, Yes has continued to tour and release new material

through the 1980s and 1990s. Their exuberant, complex music and

fusion of celestial, spiritual, and pastoral themes have influenced such

bands as Genesis, King Crimson, and Rush and has made Yes an all-

time favorite for art-rock fans worldwide.

—Dave Goldweber

F

URTHER READING:

Martin, Bill. Music of Yes: Structure and Vision in Progressive Rock.

Chicago, Open Court, 1996.

Morse, Tim, editor. Yesstories: Yes in Their Own Words. New York,

St. Martin’s, 1996.

Stump, Paul. The Music’s All That Matters: A History of Progressive

Rock. London, Quartet, 1998.

Yippies

One of the more outlandish and short-lived groups of the 1960s

American counterculture, Yippies were members of the Youth Inter-

national Party, which was officially formed in January of 1968 by

founding members Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin in Washington,

D.C. The group was essentially defunct as an activist organization

within three years. During their brief life span, the Yippies were an

influential presence at some of the later New Left’s key protests,

notably the mass demonstration at the Chicago Democratic Conven-

tion in August 1968, and the March on the Pentagon in October 1967,

YIPPIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

215

a demonstration which Rubin claimed as the birth of Yippie politics.

Frequently reviled by other New Left activist groupings for the

countercultural spirit and the carnival ethic which infused their

activism, the Yippies were renowned for a surreal style of political

dissent whose principle weapon was the public (and publicity-driven)

mockery of institutional authority of any kind. The Yippies’ departure

from an earlier generation of 1960s radicalism which had been seen

through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the first mass demonstration

against the Vietnam War the following year, is one way into the story

of what happened to the American New Left. Yippie activism

captured perfectly the chaotic final years of the ‘‘movement,’’ as the

New Left subsided into a factionalism and confusion over political

objectives which replaced the relatively focused thinking of the first

generation of 1960s radicals.

The politics which Hoffman and Rubin brought to Yippie

activism had its roots in the broad coalition of dissent which grew out

of the Civil Rights struggles of the early 1960s, and which, outside of

the southern states, grouped itself initially around Students for a

Democratic Society (SDS). Hoffman had worked for a northern

support group of the civil rights organization Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee (SNCC) before the group abandoned its

integrationist stance in 1966 and purged the organization of white

members. Rubin had enjoyed a high profile in the Free Speech

Movement (FSM) founded at Berkeley in 1964. But the presence of

poets (Allen Ginsberg) and musicians (Country Joe and the Fish, Phil

Ochs, the Fugs) in the founding ranks of the party is one way of

highlighting how far Yippie politics had travelled from the relatively

orthodox activist strategies of the first generation New Left. In the

place of politics, as such, Yippie activism preached the political

dimension of culture, stressing the subversive potential inherent in

spontaneous acts of individual dissent exercised through the free play

of imagination and the integration of an erotic theatricality into daily

life. SDS itself may never have adhered to a coherent political agenda,

but with Rubin and Hoffman, any attempt at sustaining a structured

theoretical programme was abandoned altogether. Separating itself

abruptly from the early New Left emphasis on community organizing

and relatively directed acts of protest, whilst retaining the New Left’s

pursuit of individual liberation, Yippie politics thus arrived as an

untheorised synthesis of 1950s ‘‘Beat’’ thinking, Dadaism, and

various positions taken within Marxist criticism from the 1930s

onwards (notably the thinking of Bertolt Brecht and Herbert Marcuse).

Summarized by Ochs as ‘‘merely an attack of mental disobedi-

ence on an obediently insane society,’’ the ‘‘cultural politics’’ of

Yippie took American state capitalism, the Vietnam War, and the

University as its principal targets, with Rubin and Hoffman staging a

range of theatrical street events in which the moral bankruptcy of ‘‘the

system’’ was exposed, or (ideally) was forced into exposing itself. As

early as 1965, Rubin could be found rehearsing the Yippie ethos

following his subpoena to appear before the House Un-American

Activities Committee (HUAC). Summoned before the Committee

alongside a group of radicals drawn mainly from the Maoist Progres-

sive Labor Party (PL), Rubin arrived in full American Revolutionary

War costume and stood stoned, blowing giant gum bubbles, while his

co-witnesses taunted the committee with Nazi salutes. In 1967,

Hoffman was among a group who scattered dollar bills from the

balcony of the New York stock exchange, whilst newspaper photog-

raphers captured the ensuing scramble for banknotes among the

stockbrokers on the floor below. In October of the same year,

Hoffman led a mass ‘‘exorcism of demons’’ during the March on

the Pentagon.

But it was in Chicago, during the Democratic Convention of

August 1968, that Yippie tactics were to find their defining moment.

With the war in Vietnam dragging on, and frustration mounting

among the various different groupings of the New Left, a series of

mass demonstrations were planned to coincide with the Convention.

From the very beginning, the lack of a coordinating voice or coherent

agenda threatened to collapse the demonstration from within and

bring violence to the streets of Chicago. All of the significant

dissenting groups apart from SDS agreed on the need for a large scale

protest of some kind, but each grouping had its own agenda. Dave

Dellinger of National Mobilization to end the War in Vietnam

(MOBE) argued for a combination of routine speeches, marches, and

picketing against the War, while the old guard of SDS made plans of

their own, independently of the reluctant SDS leadership. While

representatives of PL, the Black Panther Party (BBP), and New York

anarchist group the Motherfuckers also planned to attend in some

capacity, young Democrats sought to tie a more restrained demonstra-

tion to the proceedings of the Convention itself.

The confusion was compounded by local Chicago residents,

who turned out to stage a Poor People’s March, and by a late change

of heart by SDS who urged its members to attend. Against this

backdrop, Mayor Daley announced that he would turn Chicago into

an armed camp, and laid plans to call in the National Guard and the

United States Army. It was the perfect scenario for the Yippies’ own

brand of chaotic theatrical dissent. With Hoffman and Rubin at the

Yippie helm, the group embarked on a campaign of maximum

publicity and misinformation, first announcing that it would leave

town for $200,000, and then spreading the word that the City’s water

supply was to be contaminated with LSD. In Lincoln Park, the

Yippies staged a free-wheeling carnival, a ‘‘Festival of Life’’ in

opposition to the Convention’s ‘‘Festival of Death,’’ the high point of

which saw the nomination of a 150 pound pig named ‘‘Pigasus’’ as

the Yippie’s own presidential candidate (a direct reference to the

International Dada Fair of 1920, in which the figure of ‘‘Pigasus’’ had

made its first appearance). As had always seemed likely, the ‘‘Festi-

val of Life’’ was broken up by violent police action which escalated

over the following two days into a full blown riot, many officers

notoriously removing their identification badges before wading into

the crowds. Hoffmann and Rubin were arrested and charged with

conspiracy to commit violence, alongside representatives from SDS,

MOBE, and the BPP.

Before being given prison terms, Hoffman and Rubin used their

bail conditions to good effect, hounding the judge from table to table

while he lunched at a private members club, and then introduced

Yippie politics to the judicial process itself, appearing in court

dressed in judge’s clothes and the white shirt of a Chicago policeman.

Having summoned Ginsberg to appear before the court, the prosecu-

tion again drew attention to the cultural dimension of Yippie politics

by cross-examining the poet on the seditious (meaning homosexual)

content of his writings. The Yippies achieved massive press coverage

during and after the trial, and by the time that Hoffman and Rubin

were jailed in 1970, the pair had become international celebrities.

Rubin’s book Do It!, and Hoffman’s Revolution for the Hell of It

subsequently became international bestsellers. Although an organiza-

tion calling itself the Yippies continued to publish protest literature

into the 1980s, the party was more or less finished as an activist

political movement soon after the trial.

—David Holloway

YOAKAM ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

216

FURTHER READING:

Albert, Judith Clavir, and Stewart Edward Albert. The Sixties Papers:

Documents of a Rebellious Decade. New York, Praeger, 1984.

Caute, David. Sixty-Eight: The Year of the Barricades. London,

Paladin, 1988.

Hayden, Tom. Trial. London, Jonathan Cape, 1971.

Hoffman, Abbie. Revolution for the Hell of It. New York, Dial

Press, 1968.

Rubin, Jerry. Do It!. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1970.

Steigerwald, David. The Sixties and the End of Modern America. New

York, St Martin’s Press, 1995.

Yoakam, Dwight (1956—)

In 1986, Dwight Yoakam helped revitalize country music with

his twangy debut album Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. Recorded in

Los Angeles, the album mixed classic country covers with Yoakam’s

own compositions. Born in Kentucky, Yoakam grew up in Ohio,

where he attended college before moving to southern California in the

late 1970s. There he met his guitarist/producer Pete Anderson and

developed an electric honky-tonk style derived from the early record-

ings of country legend Buck Owens. Unable to break into Nashville’s

music scene, Yoakam found a niche playing to rock audiences in

California. He recorded an EP that caught the attention of record

executives and launched his career. By the early 1990s, he was

creating his own unconventional country style and scoring hits with

songs like ‘‘A Thousand Miles from Nowhere.’’ During the late

1990s, Yoakam also demonstrated his acting talent in films such as

Sling Blade and The Newton Boys.

—Anna Hunt Graves

F

URTHER READING:

Bego, Mark. Country Hunks. Chicago, Contemporary Books, 1994.

Kingsbury, Paul, Alan Axelrod, and Susan Costello, editors. Country:

The Music and the Musicians from the Beginnings to the ’90s.

New York, Abbeville Press, 1994.

McCall, Michael, Dave Hoekstra, and Janet Williams. Country Music

Stars: The Legends and the New Breed. Lincolnwood, Illinois,

Publications International, 1992.

The Young and the Restless

When The Young and the Restless premiered on March 26, 1973,

it revolutionized the entire concept of the ‘‘soap opera.’’ Historically,

the format reflected its roots in radio and, despite its jump to

television, was still an aural medium with its primary emphasis on

dialogue and story content. The Young and the Restless, however,

placed a premium on shadowy, sensuous lighting, intriguing camera

angles, and production values that provided a lavish romanticism that

appealed to female viewers and, by eroticizing the genre, changed

forever the way that ‘‘soaps’’ were photographed. But the series did

not rely on style alone. Building from the typical soap opera structure

of two intertwining families—one rich (The Brooks, who owned the

city newspaper) and one poor (the Fosters)—the show featured the

inevitable star-crossed romance. But the show ventured into new

areas, providing the first soap opera treatment of an extended rape

sequence and the aftermath of a trial. It also dealt with such issues as

euthanasia, drugs, obesity, eating disorders, mental illness, and prob-

lems of the handicapped.

In the 1980s, the show once again revolutionized the genre by

shifting its focus away from its original core families to an entirely

new set of younger characters. During the 1990s it continued to

introduce mysterious new characters while maintaining the consisten-

cy of its vision and of its storylines, a remarkable feat for the genre,

which allowed it to keep pace with its traditional competitors and the

new programs that debuted during the decade.

—Sandra Garcia-Myers

F

URTHER READING:

La Guardia, Robert. Soap World. New York, Arbor House, 1983.

Schemening, Christopher. The Soap Opera Encyclopedia. New York,

Ballantine Books, 1985.

Young, Cy (1867-1955)

‘‘Y is for Young/The magnificent Cy/People batted against him/

But I never knew why.’’ So wrote Ogden Nash about the man who

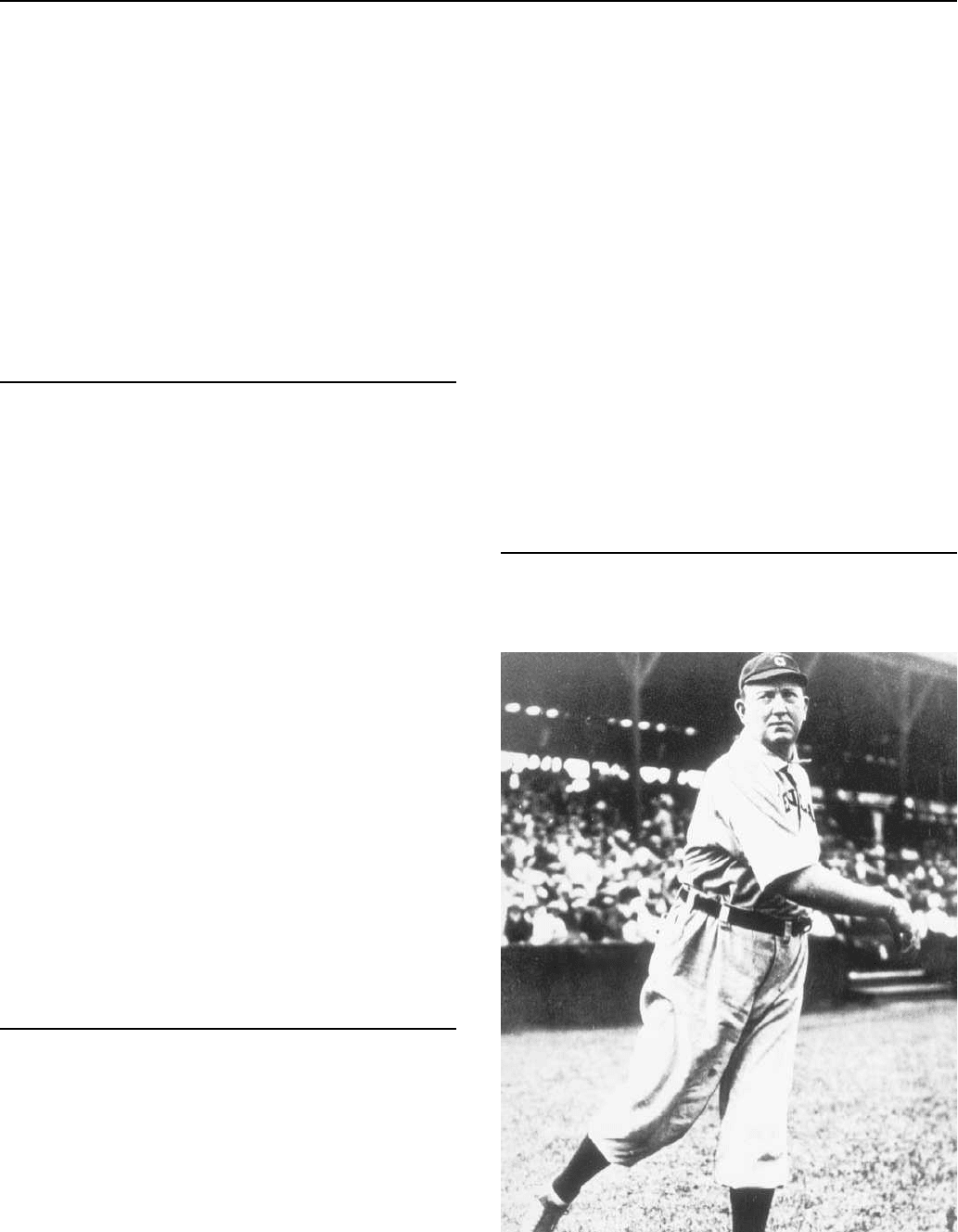

Pitcher Cy Young of the Cleveland Naps.

YOUNGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

217

won more Major League Baseball games than anyone else—Denton

True ‘‘Cy’’ Young. Young’s 511 recorded victories number nearly

100 more than the nearest challenger. And though baseball historians

have insisted that Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, and Roger Clemens

may have been better on the mound, they are confident that Young’s

lifetime totals of 7,356 innings pitched and 750 complete games will

never be broken.

Young was born in Gilmore, Ohio, on March 29, 1867. He began

his organized baseball career in nearby Canton, where he soon earned

his nickname. Some claim the name Cy is short for cyclone, referring

to his fastball, while others claim that Cy, like Rube, was a common

nickname of the age for a naive, small town ballplayer. Young began

his major league career in 1890 for the Cleveland Spiders of the

National League, where in his rookie season he had an unprepossessing

9-7 win-loss record. Two seasons later, however, he went 36-12 for

the Spiders. Young was so dominant that, before the 1893 season, the

major leagues moved the pitcher’s mound—from 50 feet from home

plate to its current distance of 60 feet, 6 inches—to give batters a

fighting chance. Yet even with the 10 extra feet, Young won 34 games

in 1893, and 35 games in 1895.

After the 1898 season Young was traded to the St. Louis

Cardinals, where he won 45 games in two seasons. Young then

jumped to the Boston Somersets (later Red Sox) of the brand-new

American League. Now in his mid-30s and in a new environment,

Young proceeded to win 193 games for Boston during eight years. In

1903 Young won 28 games and pitched Boston into the first modern

World Series, where he led his team to an upset victory over Honus

Wagner’s Pittsburgh Pirates, winning two games for his club.

Young was the first major league pitcher to throw three no-

hitters during his career—a feat later equaled by Bob Feller and

surpassed by Sandy Koufax and Nolan Ryan. In May 1904 against the

Philadelphia Athletics, Young pitched the first perfect game of the

twentieth century—a game in which he did not allow an Athletic

batter to reach base.

In 1909 Young was traded to the American League’s Cleveland

Naps (now Indians), where he won his 500th game in 1910. However,

his efficiency was declining with the onset of age and an expanding

waistline. Young admitted that, as he grew heavier, he was unable to

field bunts, and at the end of his career batters were taking advantage

of this. In 1911 he ended his career with the Boston Braves of the

National League. In his final start in September 1911, he lost a 1-0

game to Grover Cleveland Alexander, the rookie sensation for the

Phillies who would go on to win 373 games in his lifetime.

Young returned to farming in Ohio, and became a regular

celebrity at major league old-timer’s games. When the Baseball Hall

of Fame held its first election in 1936, Young narrowly missed being

inducted in the first group of immortals; voters had to select from a

pool of nineteenth-century players and a pool of twentieth-century

players, and Young’s career covered both eras. He was elected in

1937, and attended the inaugural induction ceremony in Cooperstown,

New York, in 1939, where he posed for photographs with Honus

Wagner, Babe Ruth, and Connie Mack.

Young died on November 4, 1955 in Newcomerstown, Ohio, at

the age of 88. In his honor, the following year Major League Baseball

initiated an annual award named after him: The Cy Young Award is

presented to the best pitcher in each league. In the modern era, Roger

Clemens has won five Cy Young Awards in the American League,

while Greg Maddux has won four National League Cy Youngs.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

James, Bill. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York,

Villard, 1986.

———. Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?: Baseball,

Cooperstown and the Politics of Glory. New York, Fireside, 1995.

Okrent, Daniel, and Harris Lewine. The Ultimate Baseball Book. New

York, Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer. Total Baseball. New York, Total

Sports, 1999.

Young, Loretta (1913—)

In a career that lasted from the silent films to the 1980s, Loretta

Young embodied the image of the eternal lady. She appeared as a

child extra in early films before she received her first major film role

in Laugh Clown Laugh (1928). Thereafter she was invariably cast in

roles as a young innocent. After winning an Academy Award for the

film The Farmer’s Daughter (1947), Young turned to television. Her

anthology series, The Loretta Young Show (1953-60), won her several

Emmy Awards although it was most notable for the fabulous cos-

tumes she wore. After Young’s television show went off the air she

continued to act on rare occasions, most notably in Christmas Eve, a

television movie telecast in 1986.

—Jill A. Gregg

F

URTHER READING:

Lewis, Judy. Uncommon Knowledge. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 1994.

Morella, Joe. Loretta Young: An Extraordinary Life. New York,

Delacorte Press, 1986.

Young, Neil (1945—)

A modest commercial success in the late 1970s, Neil Young’s

heavy-rocking music had a profound impact on young musicians who

started a new movement of grunge rock in the 1990s, leading many to

dub him the ‘‘godfather of grunge.’’ From his beginnings in the mid-

1960s rock band Buffalo Springfield, to his intermittent stints as a

1970s acoustic singer-songwriter and hard-rocker, on through his

1990s incarnation as grunge’s guru, Neil Young has spent his career

ducking audience expectations. This US-based Canadian expatriate’s

idiosyncratic and sometimes perverse approach to music-making has

allowed him to be perhaps the only member of his generation to

maintain critical respect years after most of his peers began artistical-

ly treading water.

On his varied and numerous albums Neil Young has worn many

hats, including those of folk-rocker, acoustic singer-songwriter,

rockabilly artist, hard-rocker, punk-rocker, techno-dance artist, and

blues guitarist. His body of work, which is matched in its depth and

breadth only by Bob Dylan, is characterized by a sense of restlessness

and experimentalism. More often than not it is the contrasting

acoustic Neil Young and distorted-guitar-meltdown Neil Young that

are most prominent.

YOUNG ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

218

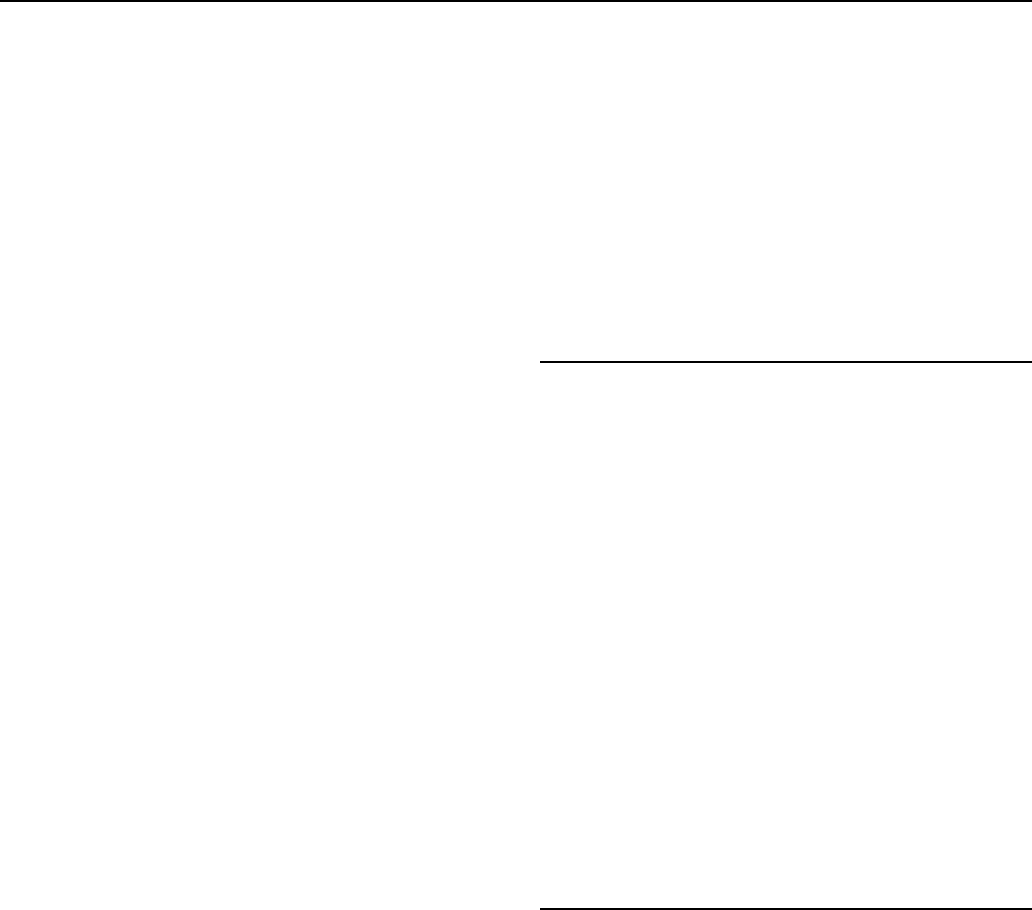

Neil Young

After leaving Buffalo Springfield he released two solo albums in

1969 that would set a pattern for the rest of his career. His self-titled

debut album featured country and folk-styled songs, utilizing acoustic

guitars buffeted by lush string sections and tasteful female backing

vocals. His second album, released a few months later, was a

collaboration with an unknown garage band called Crazy Horse, a

group Young would use throughout the rest of his career. The Crazy

Horse collaboration, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere, showed off

Young’s other half—the hard rocking, noisy side.

Most of his 1970s albums would follow this pattern, with

Harvest and Comes a Time filling his acoustic singer-songwriter

shoes and Tonight’s the Night and Zuma satisfying his craving for

molten-hot guitar distortion. Young’s artistic and commercial success

reached its zenith with 1979’s Rust Never Sleeps, which incorporated

both musical tendencies into one album split into a quiet side and a

loud side.

During the 1980s, Young’s career began to falter as he released a

series of wildly varying albums that incorporated rockabilly, garage

rock, electronic dance, folk, country, and blues. His records weren’t

selling, and his new label Geffen sued him for releasing non-

commercial, non-Neil Young-like albums. From 1983 to 1988 Young

confused and lost much of his audience, but with the release of 1989’s

Freedom he began to regain the critical and commercial clout that had

dissipated in the 1980s.

Another key to Young’s career rejuvenation (that had little to do

with his then-current output) was the changing musical climate during

the late-1980s and early-1990s: the rise of alternative guitar rock. One

marker that signaled Young’s reincarnation as the ‘‘godfather of

grunge’’ was the release of the Neil Young tribute album The Bridge

in 1989. This compilation album featured contributions by the likes of

Soul Asylum, Flaming Lips, The Pixies, Sonic Youth, and Dinosaur

Jr.—all of whom became minor or major mainstream successes. By

the early 1990s, Young was named by the likes of Nirvana and Pearl

Jam (who later played with Young) as a main influence. Young

cultivated this fandom by playing the most rocking, noisy music of his

career and by taking guitar experimentalists Sonic Youth and grunge

kings Pearl Jam on the road with him.

Young’s influence over young grunge musicians took a sad turn

when Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain referenced a well-known Neil Young

lyric in his suicide note, stating ‘‘it’s better to burn out than it is to

rust,’’ a line from ‘‘Hey Hey, My My.’’ Young reacted to this by

recording Sleeps with Angels, a mournful low-key album filled with

meditations on death and depression that served as a eulogy for

Cobain. Throughout the rest of the 1990s, Young continued to release

a series of solid but stylistically similar live and studio albums,

primarily with his longtime band Crazy Horse.

—Kembrew McLeod

F

URTHER READING:

Williams, Paul. Neil Young: Love to Burn: Thirty Years of Speaking

Out, 1966-1996. New York, Omnibus, 1997.

Young, Neil, and J. McDonough. Neil Young. New York, Random

House, 1998.

Young, Robert (1907-1998)

Robert Young is best remembered for his two successful televi-

sion shows, Father Knows Best (1954-60) and Marcus Welby, M.D.

(1969-75), which together earned him three Emmy awards. He began

his career in motion pictures of the 1930s and 1940s, invariably

playing the amiable, dependable guy who loses the girl. Young made

his film debut opposite Helen Hayes in The Sin of Madelon Claudet

(1931) and appeared in classics such as Secret Agent (1936) and The

Enchanted Cottage (1944) before turning to television. He was

married to wife Betty from 1933 until her death in 1994 and together

they had four daughters. Young left an indelible impression on

American culture of the early television era as everyone’s favorite

father figure.

—Jill A. Gregg

F

URTHER READING:

Parish, James Robert. The Hollywood Reliables. Connecticut, Arling-

ton House, 1980.

———. The MGM Stock Company: The Golden Era. Connecticut,

Arlington House, 1973.

YOUNGMANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

219

Youngman, Henny (1906-1998)

Perhaps no comedian better understood the great truism among

comedians that, regardless of the time devoted to working on an act

and the energy put into a stage performance, a comic’s material is the

key to success or failure, than the ‘‘King of the One-Liners,’’ Henny

Youngman. For more than 70 years he entertained audiences as the

quintessential Catskills comedian. His rapid-fire delivery, in which he

could tell a half dozen wisecracks in 60 seconds, was filled with

timeless bits that drew as many groans as laughs. Youngman’s theory

of comedy was to keep his jokes simple and compact. Beginning in

the mid-1920s and extending into the 1990s, he repeated countless

gags that could be immediately understood by everyone. Among his

most famous lines are such comic gems as: ‘‘I just got back from a

pleasure trip. I drove my mother-in-law to the airport,’’ ‘‘The food at

this restaurant is fit for a king. Here, King! Here, King!’’ and ‘‘A man

goes to a psychiatrist. ‘Nobody listens to me!’ The doctor says,

‘Next!’’’ In 1991, Youngman commented on his act’s enduring

popularity when he wrote, ‘‘Fads come and go in comedy. But the

one-liner always remains sacred. People laughed at these jokes when I

told them at Legs Diamond’s Hotsy Totsy Club sixty years ago—and

they’re still laughing at these same one-liners at joints I play today.’’

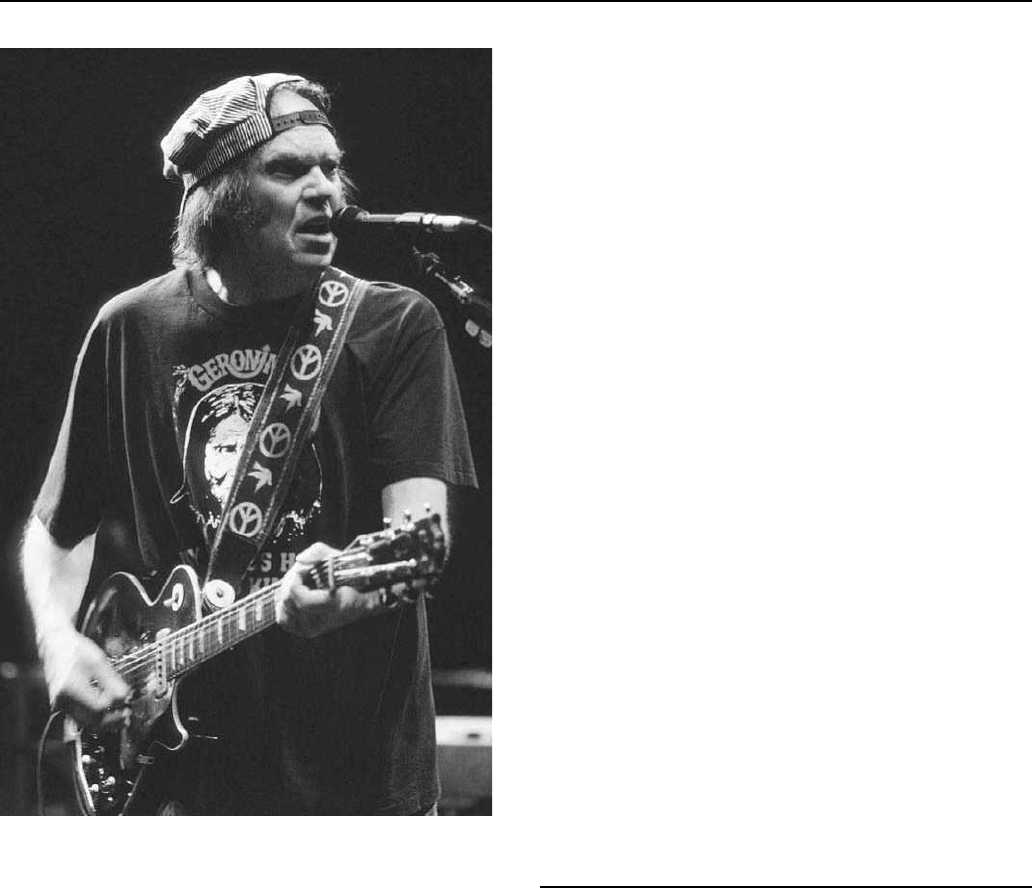

Henny Youngman

Born on March 16, 1906, in England to Russian Jewish immi-

grants who later settled in New York, Henry Youngman harbored

dreams of entering show business from an early age. His first taste of

success came as a bandleader for a quartet known as Henny Youngman

and the Swanee Syncopaters. By the mid-1920s, the group became a

regular presence in the ‘‘Borscht Belt’’—an area in the Catskill

Mountains filled with private summer resorts that catered to a

predominantly Jewish clientele. At the Swan Lake Inn, Youngman

played with his musical group, while between sets he acted as the

hotel’s ‘‘tummler,’’ a job that consisted of walking around the resort

to make sure all the guests were having a good time. The tummler

would often schmooze the male guests, dance with any unattached

female guests, and even serve as an unofficial matchmaker. To keep

the guests amused, a tummler had to have many jokes for practically

any situation at his fingertips. Youngman recalled his days in the

Catskills and their influence on his comedic style when he stated,

‘‘I’m quite sure my love of one-liners came from this mountain

laboratory. You had to be able to rat-a-tat-tat them out, on all subjects,

to all kinds of people, every hour, day or night.’’

Youngman abandoned the Swanee Syncopaters for the life of a

standup comedian when a nightclub owner asked him to fill in for an

act that failed to show. His comedy routine, honed from his days as a

tummler, was a great hit. He soon came to the attention of a rising

comedy headliner named Milton Berle, who was impressed with

Youngman’s delivery and helped him get standup gigs at small clubs

and bar mitzvahs. By the 1940s, the former tummler had become the

featured comedian on radio’s The Kate Smith Show. For two years he

had a regular six-minute spot during which he told his one-liners and

played the violin. It was in this period that Youngman acquired his

signature joke: When his wife Sadie arrived at the show with several

friends the nervous comedian wanted her to sit in the audience so he

could prepare. He grabbed an usher and told him, ‘‘Take my wife,

please.’’ The comic incorporated the humorous ad-lib into his act and

continued to use the line even after his wife died in 1987.

Youngman spent the greatest portion of his career touring

throughout the world with his unvarying act. He was proud to say he

had performed before both Queen Elizabeth II and the gangster Dutch

Schultz. No matter the audience or setting, he would take to the stage

with his prop violin and still-humorous lines. Jokes such as ‘‘My

doctor told me I was dying. I asked for a second opinion. He said

you’re ugly, too.’’ were repeated for years to audiences long familiar

with Youngman’s routine. He also frequently appeared on television

talk and variety shows into his eighties. However, his attempts to

become a regular TV performer were less successful. The summer of

1955 saw the failure of The Henny and Rocky Show, which paired him

with ex-middleweight boxing champion Rocky Graziano. In 1990, he

made a brief appearance as the emcee at the Copacabana in Martin

Scorsese’s mobster epic Goodfellas. He died in New York on

February 23, 1998.

Audiences laughed at Henny Youngman’s nearly endless supply

of one-liners because they were instantly funny and recognizable to

almost everyone. He did not offer long comic monologues, controver-

sial humor, or provocative social satire, but rather provided funny

gags for anyone who has ever had to deal with life’s more mundane

occurrences, such as bad drivers, unhelpful doctors, drunken hus-

bands, and mothers-in-law. Furthermore, his longevity allowed younger

audiences to experience a still vital performer with roots in vaude-

ville. He proved that even the most well worn jokes, like ‘‘One fellow

YOUR HIT PARADE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

220

comes up to me and says he hasn’t eaten in three days. I say, ‘Force

yourself!’’’ are still funny.

—Charles Coletta

FURTHER READING:

Youngman, Henny. Take This Book, Please. New York, Gramercy

Publishing, 1984.

Youngman, Henny, and Neal Karlen. Take My Life, Please! New

York, William Morrow, 1991.

Your Hit Parade

A landmark musical variety series on both radio (1935-1953)

and television (1950-1959, 1974), Your Hit Parade was one of the

first and most important manifestations of the musical countdown or

survey. Unlike later variations on this format, however, on Your Hit

Parade the songs were performed live by a regular cast of singers,

some of them famous (Frank Sinatra, Doris Day, Dinah Shore). The

TV version of Your Hit Parade has been cited, somewhat implausi-

bly, as a forerunner of music video and MTV.

The radio series Lucky Strike Hit Parade debuted on the NBC

Red network on April 20, 1935. During the next two years, both NBC

and CBS carried the program from time to time, until in 1937 it found

its ‘‘home’’ in the Saturday evening schedule on CBS, where it

Jill Corey rehearsing for an appearance on Your Hit Parade.

remained until 1947, when it moved back to NBC. The TV version

premiered in 1950 as a simulcast of the radio series. This arrangement

lasted until 1953, at which point the radio series was canceled. Your

Hit Parade continued on NBC until 1958, then moved back to CBS

and was canceled in 1959. A revival on CBS in 1974 lasted less than a

year and is notable mainly for employing future Love Connection host

Chuck Woolery as a singer. The cast of singers and orchestra leaders

changed frequently, especially during the show’s radio years. The TV

cast was more stable and included singers Dorothy Collins, Snooky

Lanson, Gisele MacKenzie, and Russell Arms, bandleader (and

future electronic music pioneer) Raymond Scott, and announcer

Andre Baruch. The most memorable feature of the series is probably

its opening, which consists of the sound of a tobacco auctioneer; in the

TV version there were also pictures of animated, dancing cigarettes.

As Philip Eberly points out, Your Hit Parade was one of a multitude

of musical programs sponsored by tobacco companies during the

Golden Age of American radio.

The idea behind Your Hit Parade was simple yet novel for the

1930s. Each week, the program’s house orchestra and featured

singers performed the week’s most popular songs. The length of the

show ranged from 30 to 60 minutes during the program’s history, and

the number of songs in the ‘‘hit parade’’ varied from seven to fifteen.

The American Tobacco Company owned and sponsored the program,

and the company’s ‘‘dictatorial’’ president, George Washington Hill,

‘‘personally controlled every facet of the program,’’ according to

Arnold Shaw’s account in Let’s Dance. The ranking of songs was

determined by a secret methodology administered by the company’s

advertising agency—at first, Lord and Thomas; later, Batten, Barton,

Durstine & Osborne. The hit parade placed songs in competition with

each other, and the unveiling of each week’s number one song

became an eagerly awaited event.

The TV program’s opening announcement asserted that the hit

parade was an ‘‘accurate, authentic tabulation of America’s taste in

popular music,’’ based on sheet-music sales, record sales, broadcast

airplay, and coin-machine play. The most important factor, at least

until the mid-1950s, was radio airplay—and, as Shaw points out in

Let’s Dance, Your Hit Parade itself helped to establish radio as the

major venue for American popular music. Radio’s dominance came

at the expense of vaudeville. Nevertheless, Your Hit Parade remained

rooted in Tin Pan Alley—the slang term for the music publishing

district in 1890s Manhattan, and the name that eventually came to

symbolize the (white) mainstream in American popular music. Tin

Pan Alley stood for the primacy of songs (as opposed to records) and

for a highly conventionalized song structure and performance style

(usually a verse-chorus structure, romantic or novelty lyrics, smooth

singing or ‘‘crooning,’’ and orchestration). The prevalence of songs

over records allowed Your Hit Parade to showcase its own perform-

ers along with the week’s hits. A song would often remain on the

survey for several weeks, so, for variety’s sake, the song would be

handed off from one singer to another from week to week.

The advent of the TV series prompted an additional attempt at

variety—each week, the song would receive a new ‘‘visualization.’’

Rather than delivering a straight performance into the camera, singers

were placed in a fictional and dramatic context ostensibly inspired by

the title or lyrics of the song. For example, in a 1952 episode, Snooky

Lanson portrayed a customer singing ‘‘Slow Poke’’ to the back of a

female customer at a diner. In this case, as in most others, the

visualization had only a tenuous and forced connection with the text

of the song—a ‘‘slow poke’’ sandwich appeared on the diner’s menu,

and the female customer kept Lanson waiting for a seat while he sang