Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 5: U-Z

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WISTERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

161

Alabaiso, Vincent, Kelly Smith Tunney, and Chuck Zoeller, editors.

Flash! The Associated Press Covers the World. New York,

Associated Press and Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

Associated Press. Charter and By-Laws of the Associated Press,

Incorporated in New York, December 1, 1901. New York, Associ-

ated Press, 1901.

———. Member Editorials on the Monopoly Complaint Filed by the

Government Against the Associated Press on August 28, 1942.

New York, Associated Press, 1942.

Collins, Henry M. From Pigeon Post to Wireless. London, Hodder

and Stoughton, 1925.

Diehl, Charles Sanford. The Staff Correspondent. San Antonio, Clegg

Company, 1931.

Goldstein, Norman, editor. The Associated Press Stylebook and Libel

Manual. Reading, Addison-Wesley, 1996.

Gordon, Gregory, and Ronald E. Cohen. Down to the Wire: UPI’s

Fight for Survival. New York, McGraw Hill, 1990.

MacDowall, Ian, compiler. Reuters Handbook for Journalists. Bos-

ton, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992.

Mungo, Raymond. Famous Long Ago: My Life and Hard Times with

the Liberation News Service. Boston, Beacon Press, 1970.

Read, Donald. The Power of News: The History of Reuters. New

York, Oxford University Press, 1992.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO). News Agencies, Their Structure and Operation. New

York, UNESCO, 1969.

Wister, Owen (1860-1938)

Owen Wister was one of a long line of lawyer-writers in

American literary history. This Pennsylvania-born, Harvard-educat-

ed patrician became one of America’s first and most prominent

writers of the Western genre. Popular in his own time, Wister

developed his reputation as a short story writer. He began to publish

his Western stories in 1895 and was acclaimed by many, including

Rudyard Kipling. In 1902 he wrote his most famous novel, one that is

said by many to define the Western genre: The Virginian: A Horse-

man of the Plains. Loren D. Estleman wrote in the Dictionary of

Literary Biography that: ‘‘Most if not all of the staples associated

with the western genre—fast-draw contests, the Arthurian code, and

such immortal lines as ‘‘This town ain’t big enough for both of us’’

and ‘‘When you call me that—smile!’’—first appeared in this

groundbreaking novel about one man’s championship of justice in the

wilderness. Wister’s interpretation of the West as a place where few

of the civilized concepts of social conduct apply separated his stories

from the sensational accounts then popular.’’

Wister was the only child of Sarah Butler and Owen Jones

Wister. His father was an intellectual, his mother the daughter of a

19th-century actress, Fanny Kemble. Her family had many literary

and musical connections in Europe. Wister, known as ‘‘Dan’’ to

friends and family, went to a private school near his home and then to

Harvard. There he continued a literary bent shown in earlier years by

writing for the college paper, the Crimson, and dabbling in light

opera. Although his mother encouraged his musical talents, she never

seemed happy with his writing work. A review of Wister’s corre-

spondence reveals that neither parent ever seemed fully pleased with

this capable, well-rounded Harvard Phi Beta Kappa.

After his 1882 graduation, Wister studied music in Europe and

his piano virtuosity was touted by no less than Franz Lizst. His father

opposed the young man’s love of music and pushed his own desire to

see him established in a business career in Boston. Ever the obedient

son, he returned to the United States. While the talented young Wister

languished in his position at the Union Safe Deposit Vaults of Boston,

he wrote a novel with a cousin but did not submit it for publication.

Although Wister formed many literary-minded friendships and

enjoyed the men’s clubs in Boston, his health began to deteriorate.

Following the orders of his doctor, in 1885 Wister summered in

Wyoming. The clean air revived his physical powers and ignited a

love of the West that would guide his future career. It was on the

frontier that he found his métier, both creatively and spiritually.

Wister once wrote: ‘‘One must come to the West to realize what one

may have most probably believed all one’s life long—that it is a very

much bigger place than the East and the future of America is just

bubbling and seething in bare legs and pinafores here—I don’t

wonder a man never comes back (East) after he has been here a

few years.’’

According to biographer Darwin Payne, ‘‘Wister’s deep sense of

the antithesis between the civilized East and the untamed West was

constant.’’ He did return East to study and then practice law, but ever

after he regularly vacationed in the West. Law school gave Wister a

chance to renew old Harvard friendships: he corresponded with

Robert Louis Stevenson and became close friends with Oliver Wen-

dell Holmes. But none of his letters from that period seem to indicate

any real interest in law, even after he began his practice as member of

the Pennsylvania bar in Philadelphia in 1890. The law seemed only

something to do in between trips to the West.

In 1891, after an evening with friends lamenting that the Ameri-

can West was known in the East only through rough ‘‘dime’’ novels,

Wister said that he regretted the lack of an American Rudyard Kipling

to chronicle what he called ‘‘our sagebrush country.’’ As they spoke

Wister suddenly decided to take action himself and become that sage.

He completed his first story that very night. Soon after he sent ‘‘How

Lin McLean Went West’’ and ‘‘Hank’s Woman’’ to Harper’s

magazine. ‘‘Hank’s Woman’’ is the story of an Austrian servant girl

who, fired in a visit to Yellowstone Park, marries a worthless man and

is then driven to murder. The story of McLean describes a cowboy’s

return to Massachusetts, where his mean-spirited brother finds him an

embarrassment. Both were published and found instant popular and

critical acclaim.

These tales used the same style and formula that would charac-

terize all of his Western works. The stories were based on anecdotes

he had heard, used vernacular language in dialogue-based actual

speech (which Wister painstakingly recorded in his own notebooks),

and were full of descriptions of the West. Others had already written

Western tales but it was Wister who defined the heroic, Arthurian

character of the Western hero and gave him substance.

Wister’s popularity and Western topics brought him into col-

laboration with Frederick Remington. The two worked together on a

story for an 1895 issue of Harper’s, about the evolution of the cow

puncher. Their friendship and collaboration was a ‘‘natural,’’ since

many critics both past and present felt that Remington expressed in

bronze and with paint the same feeling about the West that Wister

evoked with words. Harvard chum Theodore Roosevelt labeled

Wister an ‘‘American Kipling’’ and arranged for him to meet Kipling,

WIZARD OF OZ ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

162

then a Vermont resident, in the spring of 1895. Upon meeting Wister,

Kipling blurted out, ‘‘I approve of you thoroughly!’’ His approbation

was great balm for Wister, who suffered much of his life without the

approval of his parents—despite the fact that he now had a

national reputation.

Not long after his father’s death in 1896, Wister began to date a

second cousin, Mary Channing ‘‘Molly’’ Wister. A practical young

woman, Molly had a career in education underway when they married

on April 28, 1898, the same day the United States declared war on

Spain. For their honeymoon the Wisters toured the United States,

making a long visit to Charleston, South Carolina, where Wister’s

grandfather had signed the U.S. Constitution, and trekking to the state

of Washington so that Molly could see her ‘‘Dan’’ in his beloved

West. Molly was supportive of his writing and he supported her

activities in education. Wister’s writing flourished and their family

grew—they had three boys and three girls.

Wister soon decided to write a longer work and he began to study

the art of the novel. In 1902, Wister published The Virginian, with its

nameless hero, his schoolteacher sweetheart Molly, and the villain,

Trampas. Payne reports that the New York Times Saturday Review of

Books, in its review of The Virginian claimed: ‘‘Owen Wister has

come pretty near to writing the American Novel.’’ Henry James wrote

enthusiastically about the novel, which Wister had dedicated to his

friend, Theodore Roosevelt. The Virginian was a financial, critical,

and popular success. Wister himself turned it into play and it

continued to be popular long after his death. According to Estleman,

‘‘If the importance of a work is evaluated by the number of people it

reaches, The Virginian stands among the three or four important

books this century has produced. By 1952, fifty years after its first

publication, eighteen million copies had been sold, and it had been

read by more Americans than any other book.’’

Four movies were made of the book during the century, in 1914

(with a screenplay by D. W. Griffith), 1923, 1929, and 1946. Of the

four movie versions, the best known was the 1929 version starring

Gary Cooper in the title role and directed by Victor Fleming. Cooper

seemed best to capture the near-mythic nature of Wister’s hero. The

nameless Virginian is an American knight—a soft-spoken gentleman

who is ready and able to survive and even tame the travails and

splendid chaos of the West. Wister’s novel defined our mythic

Western hero as a quiet but volcanic strong man who plays by the

rules. The story was also adapted for the small screen in a television

series that ran from 1962 to 1966. The Virginian was thus one of the

few stories that shaped Americans’ understanding of the American

West and of the place of individuals within it.

Most of his later fiction deals with the conflict between the good

and the bad within the West. According to Jane Tompkins in West of

Everything, his work is realistic in setting, situation, and characters—

more so than rival fiction of the period—but still tending toward the

sentimental and melodramatic. Wister tried to expand his writing

style by writing his own ‘‘novel of manners,’’ modeled on Flaubert’s

Madame Bovary but set in genteel Charleston, South Carolina. The

novel, Lady Baltimore, was not critically acclaimed and had moderate

sales in its time. In 1913, his wife died and he no longer wrote fiction.

He began several projects and then took the path of political and non-

fiction writing in the era just before World War I.

His major post-Virginian achievement was a biography of his

old friend, Theodore Roosevelt, and many articles about his past

acquaintances and friendships. At the end of his life Wister was no

longer remembered as a great literary figure. He died on July 21,

1938, just seven days after his 78th birthday. His reputation was

resuscitated late in the century by the Western Writers of America,

which named a major award after Wister, and by an increasing

number of scholars willing to take his work seriously.

—Joan Leotta

F

URTHER READING:

Cobbs, John L. Owen Wister. Boston, Twayne, 1984.

Estleman, Loren D. The Wister Trace: Classic Novels of the American

Frontier. Ottawa, Illinois, Jameson Books, 1987.

Folsom, James K., editor. The Western: A Collection of Critical

Essays, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1979.

Payne, Darwyn. Owen Wister: Chronicler of the West, Gentleman of

the East. Dallas, Texas, Southern Methodist University Press, 1985.

Tompkins, Jane. West of Everything. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1992.

White, G. Edward. The Eastern Establishment and the Western

Experience: The West of Frederick Remington, Theodore Roose-

velt, and Owen Wister. Austin, University of Texas Press, 1989.

Wister, Owen. Owen Wister’s West: Selected Articles, edited by

Robert Murray Davis. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico

Press, 1987.

———. The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains. New York,

Macmillan, 1902.

The Wizard of Oz

The 1939 Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM) film The Wizard of

Oz, based on L. Frank Baum’s 1900 book was hugely influential. Its

simple message—that there is no place like home, and that you have

the power to achieve what you most desire—had a general appeal to

the American public. Starting in 1956, a new generation of American

children was annually entranced by the television showing of Doro-

thy’s journey down the Yellow Brick Road.

In the film, after a cyclone carries her to Oz, Dorothy meets the

Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion, and they set

off together for the Emerald City in search of what they most desire:

for Dorothy, a home; for the Scarecrow, a brain; for the Tin Wood-

man, a heart; and for the Cowardly Lion, courage. When they kill the

Wicked Witch of the West and go to the Wizard for their promised

reward, they discover he is nothing but a humbug. Nevertheless, he

supplies them with the symbols of what they already possess—a

degree for the Scarecrow, a ticking heart-shaped clock for the Tin

Woodman, and a medal for the Cowardly Lion. Glinda the Good

Witch helps Dorothy use the magic in the ruby slippers she has been

wearing all along to whisk her back to Kansas.

The film was made during the heyday of the studio system and

the golden era of MGM. Directed by Victor Fleming (among others),

it starred Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, Bert Lahr, Frank

Morgan, and Margaret Hamilton. From the beginning, it was a

production beset by trouble: cast changes, director changes, injuries,

and script rewrites kept cast and crew busy for 23 weeks, the longest

shoot in MGM history.

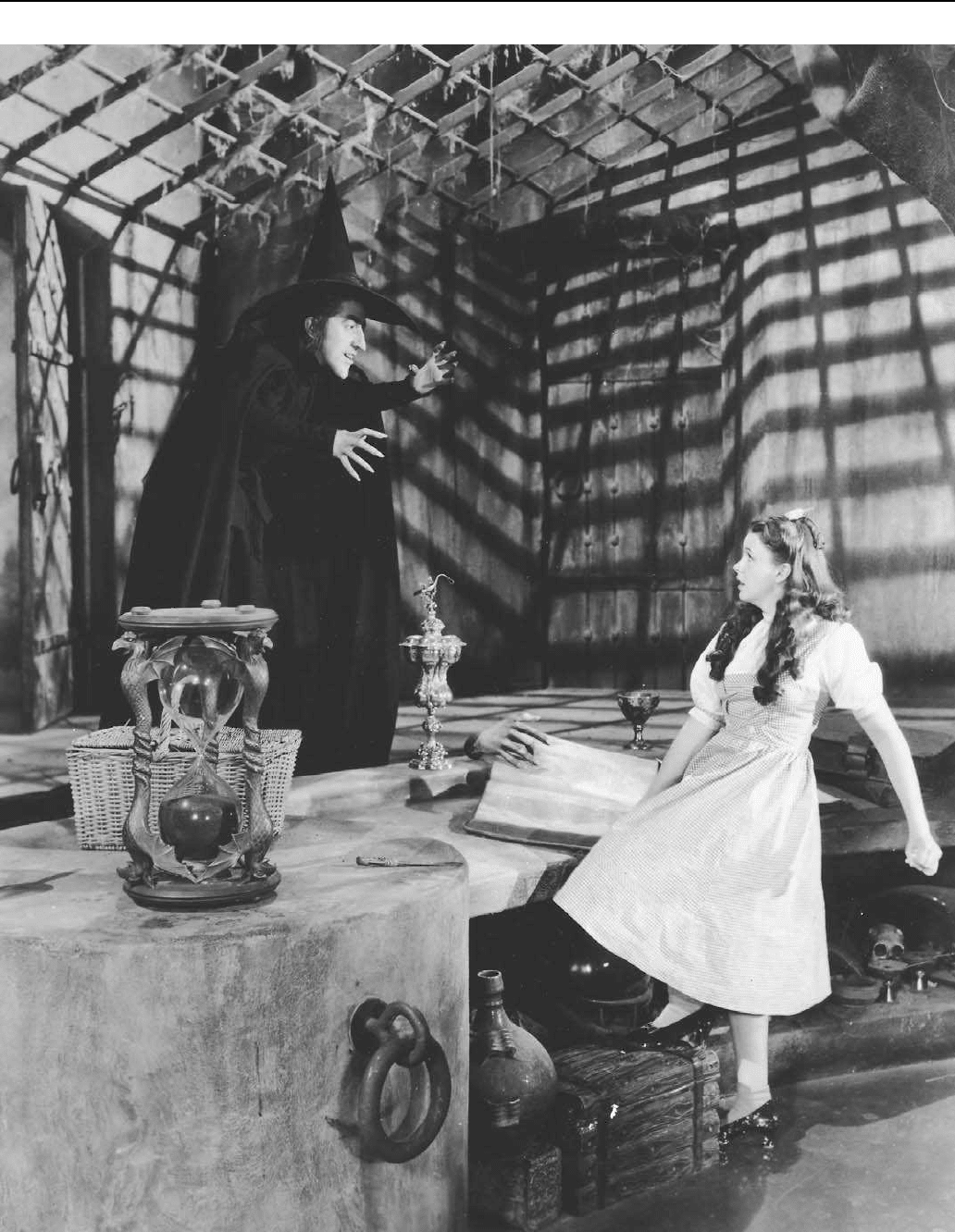

The opening and closing Kansas scenes were filmed in black-

and-white, while the Oz scenes were done in sumptuous (and expen-

sive) Technicolor. Dorothy’s amazement at entering the world of

WIZARD OF OZENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

163

A scene from the film The Wizard of Oz, with Judy Garland as Dorothy.

WKRP IN CINCINNATI ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

164

color mirrored audiences’ feelings about the new technology. The

importance of wonder did not stop there: Jack Haley (the Tin

Woodman) created the breathless, slightly stilted way he and Ray

Bolger (as the Scarecrow) would speak to Dorothy. Haley told Victor

Fleming, ‘‘I want to talk the way I talk when I’m telling a story to my

five-year-old son,’’ and Bolger agreed, saying later ‘‘I tried to get a

sound in my voice that was complete wonderment.’’ Haley, Bolger,

and Lahr (the Cowardly Lion) came out of the vaudeville tradition and

filled the movie with the kind of jokes and physical humor with which

stage audiences were already familiar.

Frank Morgan, as the Wizard, perfectly embodied the harmless-

trickster aspects of his character. Margaret Hamilton, as the Wicked

Witch of the West, scared many youngsters with her bright green skin

and high-pitched cackle. L. Frank Baum, the original author of the

story, had wanted to create a fairy tale that eliminated ‘‘all the horrible

and blood-curdling incidents’’ of fairy tales, one that ‘‘aspires to

being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are

retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out.’’ The

Wicked Witch, however, terrorized children in the audience—the

scene where Dorothy watches Aunt Em in the crystal ball dissolve

into the Witch has been interpreted by psychologists to symbolize the

unpleasant fusion of good and bad mother figures.

The film was released in 1939 to receptive audiences, but was

overshadowed by the epic Gone with the Wind and did not start to turn

a real profit until CBS bought it for television in 1956. From then on, it

was shown annually, and by the year 2000 held seven of the places in

a list of the top 25 highest-rated movies on network television (no

other film held more than one spot.) The aggregate audience from

1956 until the year 2000 was more than one billion people. In 1998,

The Wizard of Oz was re-released on the big-screen.

The songs, by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg, were hugely

popular from the start. ‘‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’’—Judy

Garland’s plaintive song of a place where ‘‘the dreams that you dare

to dream really do come true’’—became a jazz standard in the United

States and an anthem of hope in England during World War II.

Garland’s version remains the most famous, but pop artists as diverse

as Willie Nelson, Tori Amos, and Stevie Ray Vaughan recorded

covers. After gay icon Garland’s death, the rainbow in her song

became a gay coat-of-arms.

The Wizard of Oz spawned numerous remakes and sequels,

including animated cartoons, a Broadway show, ‘‘Oz on Ice,’’ and

The Wiz, an all-black, urban revision of the original film, starring

Diana Ross as Dorothy and Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. Many

films, including Star Wars, David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, and John

Boorman’s Zardoz, contain major allusions to The Wizard of Oz—

minor references to it are pervasive in American movies. In literature,

dark revisionist fantasies, including Geoff Ryman’s Was, a bleak Oz

story that incorporates AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syn-

drome), child abuse, and Judy Garland’s childhood, and Gregory

Maguire’s Wicked, an Oz prequel written from the witch’s point of

view, owe great debts to the film. It was also influential in popular

music—Elton John titled an album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,

Ozzie Osbourne titled one Blizzard of Oz, and Electric Light Orches-

tra’s Eldorado album cover showed a pair of green hands reaching for

Dorothy’s ruby slippers, with no explanation required.

The Wizard of Oz film seeped into the everyday life of Ameri-

cans in countless ways. Dunkin’ Donuts named its donut-hole crea-

tions ‘‘Munchkins’’ after the little-people inhabitants of Munchkinland,

where Dorothy’s house lands in Oz. Quotes from the movie—‘‘Toto,

I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore’’; ‘‘Lions, and tigers, and

bears, oh my’’; ‘‘Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain’’—

were emblazoned on t-shirts. A 25-cent postage stamp depicting

Dorothy and Toto was released in 1989 as part of the United States

Postal Service ‘‘Classic Films’’ series. References to the film showed

up in political cartoons, advertisements, and greeting cards. There

was an Oz theme park, an Oz fan club, and a series of Oz conventions.

During the Watergate scandal, Nixon was compared more than once

to the humbug Wizard. The plot of the first episode of the 1970s

television program H.R. Pufnstuf was unmistakably borrowed from

The Wizard of Oz. And in the 1980s and 1990s, self-help gurus used

the Yellow Brick Road as a metaphor for the quest for self-knowledge.

Popular myths also sprung up about the film, such as its

supposed synchronicity with Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon

album, and exaggerated stories of the Munchkin actors’ bad behavior

on the set. A myth about a Munchkin suicide visible in the back of one

scene persists despite being debunked numerous times.

When the film was originally released, with the tagline ‘‘The

Greatest Picture in the History of Entertainment,’’ MGM launched an

aggressive merchandising campaign; objects from this campaign now

fetch high prices as collectors’ items. Memorabilia from the film is

also extremely valuable: one pair of Judy Garland’s ruby slippers is

on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington,

D.C., at the National Museum of American History; another pair was

auctioned at Christie’s for $165,000 in 1988.

Film critic Roger Ebert attempts to explain the movie’s populari-

ty, saying: ‘‘The Wizard of Oz fills such a large space in our

imagination. It somehow seems real and important in a way most

movies don’t. Is that because we see it first when we’re young? Or

simply because it is a wonderful movie? Or because it sounds some

buried universal note, some archetype or deeply felt myth?’’ Ebert

leans toward the last possibility, and indeed, Baum deliberately set

out in 1900 to create a uniquely American fairy tale, one with timeless

appeal to all the ‘‘young in heart.’’ The film—and all that followed—

made his dream come true.

—Jessy Randall

F

URTHER READING:

Baum, Frank Joslyn, and Russell P. Macfall. To Please a Child: A

Biography of L. Frank Baum, Royal Historian of Oz. Chicago,

Reilly & Lee, 1961.

Fricke, John, Jay Scarfone, and William Stillman. The Wizard of Oz:

The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. New York,

Warner Books, 1989.

Harmetz, Aljean. The Making of ‘‘The Wizard of Oz.’’ New York,

Delta, 1989.

Hearn, Michael Patrick. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. New York,

Clarkson Potter, 1973.

Shipman, David. Judy Garland: The Secret Life of an American

Legend. New York, Hyperion, 1993.

Vare, Ethlie Ann, editor. Rainbow: A Star-Studded Tribute to Judy

Garland. New York, Boulevard Books, 1998.

WKRP in Cincinnati

The sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati mirrored late-1970s American

culture through the lives and antics of the employees of a small AM

WOBBLIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

165

radio station. In its four-year run on CBS from 1978 to 1982, WKRP

developed one of the best ensemble casts on television and produced

some of the more memorable scenes from the period. The show’s

ability to build contemporary issues into many of the stories makes it a

time capsule for the period, as it dealt with issues such as alcoholism,

urban renewal, drugs, infidelity, crime, guns, gangs, elections, and

even other television shows. In a classic episode about a Thanksgiv-

ing promotion gone bad, Les Nesman’s report—a dead-on take from

the Hindenburg disaster—and Arthur Carlson’s trailing words—‘‘As

God is my witness I thought turkeys could fly’’—crackle with the

show’s characteristic intelligence and humor.

—Frank E. Clark

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network TV Shows. 5th Edition. New York, Ballantine, 1992.

Kassel, Michael. America’s Favorite Radio Station: WKRP in Cin-

cinnati. Bowling Green, Popular Press, 1993.

McNeil, Alex. Total Television: A Comprehensive Guide to Pro-

gramming from 1948 to the Present. 3rd edition. New York,

Penguin Books, 1991.

Wobblies

A radical labor union committed to empowering all workers,

especially the nonskilled laborers excluded from the American

Federation of Labor (AFL), the so-called Wobblies, members of the

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), played a pivotal role in

America’s labor history. Believing that the nation’s most exploited

and poorest workers deserved a voice, the Wobblies called for ‘‘One

Big Union’’ that would challenge the capitalist system first in the

United States and later worldwide.

In 1905 a group of two hundred radical labor activists met in

Chicago and formed the IWW. The group was overwhelmingly leftist

and called for the ultimate overthrow of capitalism worldwide.

Immediately feared by most and despised by AFL leader Samuel

Gompers, the Wobblies challenged the status quo and fought for the

rights of America’s working poor. The Wobblies planned to do what

no union had tried before: unite blacks, immigrants, and assembly-

line workers into one powerful force.

IWW leaders included some of the most famous names in

American labor history, such as Big Bill Haywood, head of the

Western Federation of Miners; Mary ‘‘Mother’’ Jones; and Eugene

Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party. Initially, the ranks of the IWW

were filled with western miners under Haywood’s control. These

individuals became increasingly militant as they were marginalized

by the AFL. Traveling hobo-like by train, IWW organizers fanned out

across the nation. Wobbly songwriters like Joe Hill immortalized the

union through humorous folk songs. The simple call for an inclusive

union representing all workers took hold. At its peak, 1912-1917,

IWW membership approached 150,000, although only 5,000 to

10,000 were full-time members.

Long before the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia, the courageous

and militant Wobblies were calling for a socialist revolution and

began organizing strikes around the nation as a prelude to a general

worldwide strike among the working class. The strikes often turned

bloody, but the Wobblies continued to fight. They were attacked by

the newspapers, the courts, the police, and goon squads formed to

protect the interests of corporations. The IWW led important strikes at

Lawrence, Massachusetts (1912); Paterson, New Jersey (1913); and

Akron, Ohio (1913). As the Wobblies battled for free speech and

higher wages across the nation, a legendary folklore developed

regarding the union because of the violence and mayhem that seemed

to follow them everywhere. The Wobblies became the scourge of

middle-class America, especially in the highly charged atmosphere of

World War I and the postwar Red Scare. The IWW, according to labor

historian Melvyn Dubofsky in We Shall Be All, became ‘‘romanti-

cized and mythologized.’’ The reality was that the Wobblies mixed

Marxism and Darwinism with American ideals to produce a unique

brand of radicalism.

As the Wobbly ‘‘menace’’ became more influential, American

leaders took action to limit the union’s power. World War I provided

the diversion the government needed to crush the IWW once and for

all. Anti-labor forces labeled the IWW subversive allies of both

Germany and Bolshevik Russia; one senator called the group ‘‘Impe-

rial Wilhelm’s Warriors.’’ President Woodrow Wilson and his attor-

ney general believed the Wobblies should be suppressed. On Septem-

ber 5, 1917, justice department agents raided every IWW headquarters in

the country, seizing five tons of written material. By the end of

September nearly two hundred Wobbly leaders had been arrested on

sedition and espionage charges. In April 1918, 101 IWW activists

went on trial, which lasted five months and was the nation’s longest

criminal trial to date. All the defendants were found guilty, and fifteen

were sentenced to twenty years in prison, including Haywood, who

jumped bail and fled to the Soviet Union where he died a decade later.

The lasting importance of the IWW was bringing unskilled

workers into labor’s mainstream. After the demise of the Wobblies,

the AFL gradually became more inclusive and political. The Con-

gress of Industrial Organizations, founded in 1935 by another mining

leader, John L. Lewis, successfully organized unskilled workers. In

1955 the AFL and CIO merged to form the AFL-CIO, America’s

leading trade union throughout the second half of the century.

The heyday of the IWW lasted less than twenty years, but in that

short span it took hold of the nation’s conscience. Nearly forgotten

today, the Wobbly spirit still can be found in novels by John Dos

Passos and Wallace Stegner, as well as numerous plays and movies.

By the 1950s and 1960s, IWW songs, collected in the famous Little

Red Song Book, were rediscovered by a new generation of activists

fighting for civil rights and an end to the Vietnam War.

—Bob Batchelor

F

URTHER READING:

Carlson, Peter. Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood.

New York, W. W. Norton, 1983.

Conlin, Joseph R., editor. At the Point of Production: The Local

History of the IWW. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1981.

Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial

Workers of the World. Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace,

the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865-1925. New York,

Oxford University Press, 1987.

WODEHOUSE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

166

Wodehouse, P. G. (1881-1975)

P. G. Wodehouse’s best known creations are upper-class incom-

petent Bertie Wooster, and his capable servant, Jeeves, who first

appeared in the story ‘‘Extricating Young Gussie’’ in 1917. His

satirical view of the Jazz Age is both affectionate and incisive; he

pokes fun at such emblems of the inter-war period as flappers,

gangsters, the fascist ‘‘Black Shirts,’’ and the dreaded moralizing

aunt. Born Pelham Grenville Wodehouse in Guildford, Surrey, and

educated at Dulwich College in London, he took United States

citizenship in 1955, having lived there from 1909. A journalist and

writer of over ninety books, Wodehouse also worked as a lyricist and

writer with such luminaries as Jerome Kern and George Gershwin.

Aged ninety-three, newly knighted, and with a waxwork of himself in

Madame Tussaud’s in London, he declared himself satisfied. He died

the same year.

—Chris Routledge

F

URTHER READING:

Green, B. P. G. Wodehouse: A Literary Biography. London, Pavilion

Books, 1981.

Wodehouse, P. G. Over Seventy: An Autobiography with Digressions.

London, Jenkins, 1957.

Wolfe, Nero

See Stout, Rex

Wolfe, Tom (1931—)

Since the 1960s, American journalist Tom Wolfe has been one

of the chief chroniclers of the times. Known for analyzing trends and

exposing inherent cultural absurdities, Wolfe has coined terminology

such as ‘‘radical chic’’ and ‘‘the Me decade.’’ He has the knack for

pinpointing an age, wrapping it up in vivid and readable prose, and

presenting it back to society as a kind of mirror. Wolfe was one of the

first in a cadre of writers—among them, Jimmy Breslin, Truman

Capote, Hunter Thompson, and Gay Talese—to adopt a style called

the New Journalism, the practice of writing nonfiction with many of

the traditional storytelling elements of fiction. In addition, Wolfe

distinguished himself by his frequent use of unorthodox punctuation

and spelling and by peppering his text with interjections and ono-

matopoeia. Some of his most famous works include The Kandy-

Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamlined Baby (1965), The Electric

Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), and Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the

Flak Catchers (1970). He was also applauded for his 1979 portrait of

the early era of the American space program, The Right Stuff, and for

his first, and so far only, novel, 1987’s social satire Bonfire of the

Vanities. Over a decade later, in late 1998, Wolfe again won warm

critical reception with his second novel, A Man in Full, which shot to

the top of the best-seller lists.

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe, Jr. was born on March 2, 1931, in

Richmond, Virginia. In high school, Wolfe was the editor of his

student newspaper, and he went on to serve as sports editor of the

campus paper at Washington and Lee University in Lexington,

Virginia, where he also cofounded the literary quarterly Shenandoah.

He received his bachelor’s degree in English in 1951. After that, he

went on to obtain a doctoral degree in American studies at Yale

University in 1957. Meanwhile, eager to begin a professional writing

career, he sent out one hundred letters to publications, but received

just three responses—two of them negative. He thus went to work at

the Springfield Union in Massachusetts from 1956 to 1959, then

moved to the Washington Post in June of 1959, where he won awards

for reporting and humor.

In 1962 Wolfe began working at the New York Herald Tribune.

There, he had the opportunity to contribute to its Sunday supplement,

New York, which later became an independent magazine. During a

newspaper strike, Wolfe landed an assignment for Esquire writing

about the custom car craze in California. Though he was enamored of

his subject matter—the chrome-laden, supercharged vehicles and

their young enthusiasts—Wolfe told his editor that he could not

manage to construct a story. He was told to type up his notes and send

them in so that another writer could do the job. The editor was so

struck with Wolfe’s lengthy stream-of-consciousness descriptions

and musings that he ran it unaltered. This became ‘‘There Goes

(Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Stream-

line Baby,’’ which Wolfe later included in his 1965 collection of

essays, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamlined Baby. The

article’s fertile detail, hip language, and unusual punctuation became

Wolfe’s trademarks.

Early on, Wolfe’s style was characterized as gimmicky, but also

applauded as the best way to approach some of the wacky topics he

covered for his pieces. How better to record the rise in LSD and

growth of the hippies than to use the language of the people about

whom he wrote? Indeed, Wolfe eloquently outlined the 1960s drug

era in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test in documenting the antics of

novelist Ken Kesey and his ‘‘Merry Pranksters,’’ a group of LSD

users on the West Coast who personified hippie culture. Subsequent-

ly, Wolfe delighted some and angered others in Radical Chic and

Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, actually two separate long essays.

Radical Chic was his bitingly humorous depiction of a fundraising

party given by the white bourgeois in support of the Black Panthers.

His satiric observations cut too close to the bone for some white

liberals and black activists; still others were appalled by his seemingly

cruel mimicry. However, many critics praised his sharp eye and

sociological approach.

Wolfe toned down his style somewhat to pen The Right Stuff in

1979, a best-seller explaining the rise of NASA and the birth of the

program to send an American into space. Much of the book’s focus

was on the people involved, from Chuck Yeager, the Air Force pilot

who first broke the sound barrier, to the Apollo Seven astronauts and

their families. It gave a personal, behind-the-scenes look at the lives

affected by the space program, painting the men not only as heroes

with the requisite ‘‘stuff’’ needed to fulfill such a duty, but as regular

humans with failings and feelings as well. Wolfe’s nonfiction through-

out his career was as gripping as fiction due to his use of the genre’s

devices: dialogue, a shifting point-of-view, character development,

and intensive descriptions of setting and other physical qualities in a

scene. He finally tried his hand at a novel in 1987, publishing the

widely praised Bonfire of the Vanities, a keen and darkly witty profile

of 1980s Americana, from the bottom social strata to the top. His

second novel, A Man in Full (1998), dealt with similar themes of race

and class in late-twentieth-century America, but took place in the up-

and-coming metropolis of Atlanta, Georgia. A Man in Full was

WOLFMAN JACKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

167

trademark Wolfe, featuring encylopedic knowledge of a variety of

subcultures and incisive observations about each. It, too, was a

popular and critical success.

Being one of the most visible purveyors of the art known as New

Journalism, Wolfe co-edited and contributed to an anthology titled

The New Journalism in 1973. A staple in some college journalism

courses, the volume expertly collects some of the finest examples of

the practice from top names in the field and explained the constructs

involved. Wolfe has also served as a contributing editor of Esquire

magazine since 1977. Though his novel was considered a fine

achievement, his contribution to the field of literature generally rests

on his nonfiction sociocultural examinations.

—Geri Speace

F

URTHER READING:

Lounsberry, Barbara, ‘‘Tom Wolfe.’’ Dictionary of Literary Biogra-

phy, Volume 152: American Novelists Since World War II, Fourth

Series. James Giles and Wanda Giles, editors. Detroit, Gale

Research, 1995.

McKeen, William. Tom Wolfe. New York, Twayne, 1995.

Salamon, Julie. The Devil’s Candy: The Bonfire of the Vanities Goes

to Hollywood. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Scura, Dorothy M., editor. Conversations with Tom Wolfe. Jackson,

University of Mississippi Press, 1990.

Shomette, Doug, editor. The Critical Response to Tom Wolfe. Westport,

Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1992.

Wolfe, Tom, and E.W. Johnson, editors. The New Journalism. New

York, Harper, 1973.

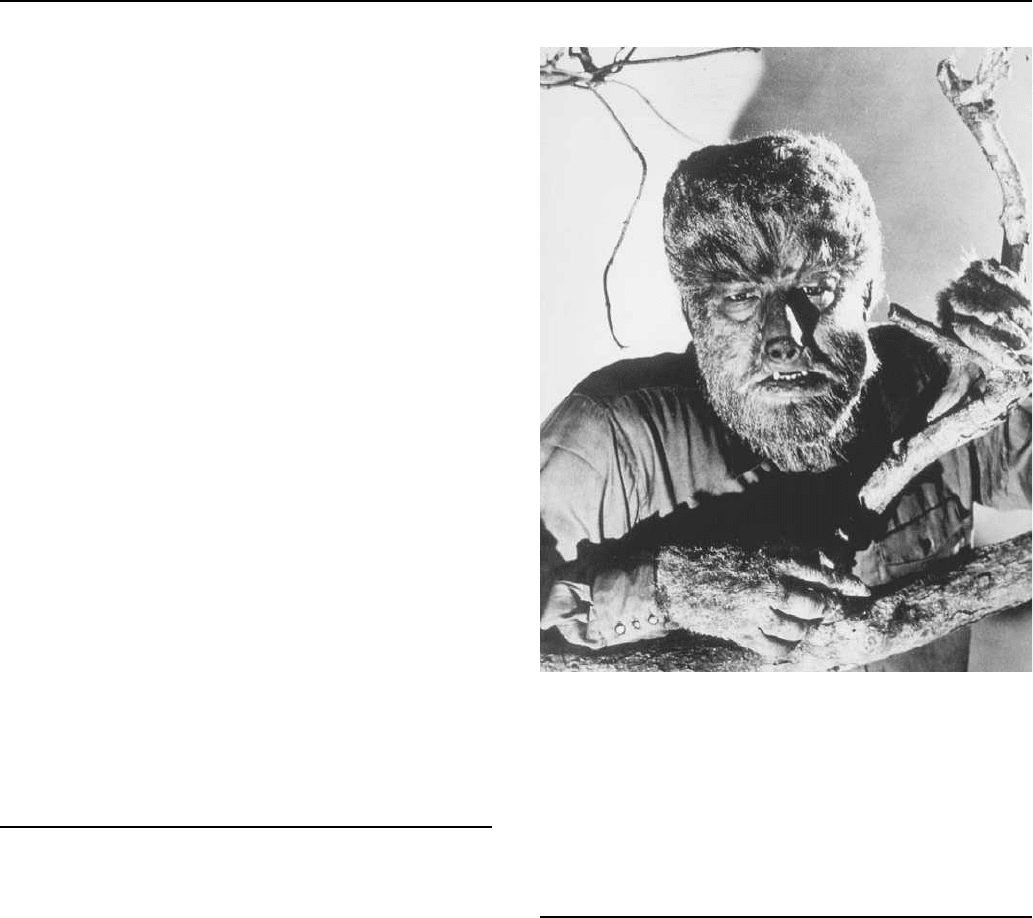

The Wolfman

The Wolfman—a bipedal, cinematic version of the werewolf

archetype—dramatically embodies the Jekyll/Hyde (superego/id) di-

chotomy present in us all. The Wolfman first took center stage in

Universal’s Werewolf of London (1935), starring Henry Hull in a role

reprised decades later by Jack Nicholson (Wolf, 1994). Soon after,

Curt Siodmak (Donovan’s Brain) finished the screenplay for Univer-

sal’s latest horror classic, The Wolf Man (1941), directed by George

Waggner. Lon Chaney, Jr. starred as Lawrence Talbot, an American-

educated Welshman who wants nothing more than to be cured of his

irrepressible lycanthropy. Make-up king Jack Pierce devised an

elaborate yak-hair costume for Chaney that would come to serve as

the template for countless Halloween masks. Siodmak’s story dif-

fered from previous werewolf tales in emphasizing the repressed

sexual energy symbolically motivating Talbot’s full-moon transfor-

mations. Four more Chaney-driven Wolfman films came out in the

1940s; numerous imitators, updates, and spoofs have since followed.

—Steven Schneider

F

URTHER READING:

Skal, David. ‘‘‘I Used to Know Your Daddy’: The Horrors of War,

Part Two.’’ The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror.

New York, W.W. Norton, 1993, 211-227.

Lon Chaney Jr. in character in the film Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman.

Twitchell, James B. ‘‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Werewolf.’’ Dreadful

Pleasures: An Anatomy of Modern Horror. New York, Oxford

University Press, 1985, 204-257.

Wolfman Jack (1938-1995)

With his trademark gravelly voice and howl, disc jockey Wolfman

Jack became a cultural icon over the airwaves during the 1960s and

was integral in popularizing rock music. The first radio personality to

introduce rhythm-and-blues music to a mainstream audience, he

opened the doors for African American artists to reach widespread

success in the music world. The Wolfman did more than announce

songs over the radio; his unique personality lent a context to the sound

of a new generation and made him the undisputed voice of rock

and roll.

Wolfman Jack was born Robert Weston Smith in Brooklyn, New

York, on January 21, 1938 and grew up in a middle-class environ-

ment. Always fond of music, as a teenager he would pretend he was a

disc jockey using his own stereo equipment. After some odd jobs

selling encyclopedias and Fuller brushes, Wolfman Jack attended the

National Academy of Broadcasting in Washington, D.C. He got his

professional start in 1960 at WYOU in Newport News, Virginia, a

station that catered to a mostly black audience. There, the Wolfman

began experimenting with on-air characters, and off the air, hosted

dance parties. In 1962, he crossed the border to begin airing a show on

WOLFMAN JACK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

168

Wolfman Jack

Mexican radio’s XERF, which held an extremely powerful 250,000-

watt signal that reached across much of the continent. At this job, Bob

Smith developed his Wolfman Jack persona.

Wolfman Jack’s raspy voice and on-air howls and commands to

‘‘get nekkid’’ caught the attention of young music fans across the

country. Unfortunately, the Federal Trade Commission was interest-

ed in his advertisements for an array of products over his show,

including drug paraphernalia and sugar pills that supposedly helped

with sexual arousal, which led to the demise of the station’s profits.

Meanwhile, however, the Wolfman became known for playing a

range of black artists such as Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Clarence

Carter, and more, leading to the crossover of African American artists

into white culture. Though record company executives were pleased

to see their markets broadening, not everyone was thrilled with the

development, since integration was still a new concept. Later, when

Wolfman Jack moved back to Louisiana and hosted racially mixed

dances, the Ku Klux Klan burned crosses on his lawn. Subsequently,

Bob Smith kept Wolfman Jack within the confines of the studio to

avoid hostility.

Later, Wolfman Jack moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where

he ran a small local station and sent taped shows down to XERF.

Wishing to resume live on-air performances, in 1966 he and a partner

opened their own station on Sunset Strip in Los Angeles, which

flourished until 1971. After that folded, Wolfman Jack accepted a

humble salary at KDAY and also began hosting the television show

Midnight Special on NBC, airing from 1972 to 1981. He appeared in

most of the episodes. He also had a part as himself in the hit George

Lucas film American Graffiti, a nostalgia movie about a group of

teenagers in the early 1960s. The appearance finally put a face to the

name for fans, who were reassured to discover that the Wolfman

looked every bit the part, with bulging eyes and a bushy beard,

sideburns, and hairstyle. Wolfman Jack used this publicity to land

jobs on commercials and appearing at concerts and conventions. He

was also a guest on Hollywood Squares, and began working on

WNBC in New York City hosting a radio show. In addition, he lent

his voice to the rock song ‘‘Clap for the Wolfman’’ by the Guess Who.

In the early 1990s, Wolfman Jack flew from his home in North

Carolina to Washington, D.C. each Friday to host the syndicated radio

WONDERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

169

oldies program Live from Planet Hollywood on WXTR-FM. In 1995,

he published his autobiography, which related the ups and downs of

his career, from hobnobbing with other celebrities to his battle with a

cocaine addiction. Shortly after completing a 20-day tour to promote

the book, he died of a heart attack at his home in Belvidere, North

Carolina, on July 1, 1995. He was survived by his wife of 34 years,

Elizabeth ‘‘Lou’’ Lamb Smith, and his two children, Todd Weston

Smith and Joy Renee Smith.

—Geri Speace

F

URTHER READING:

Stark, Phyllis. ‘‘Wolfman Dies on Cusp of Greatness.’’ Billboard.

July 15, 1995, 4.

Wolfman Jack with Byron Lauren. Have Mercy! Confessions of the

Original Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal. New York, Warner Books, 1995.

Woman’s Day

Begun during the 1930s depression, Woman’s Day magazine

‘‘like the supermarket. . . helped to change the habits of the American

family,’’ according to Helen Woodward in The Lady Persuaders.

Woman’s Day began as a giveaway menu leaflet, the ‘‘A&P Menu

Sheet,’’ published and distributed to its customers by the Great

Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company. The sheet ‘‘told the housewife how

to get the most for her food dollar, then how to use the food purchased

to provide her family with appetizing and nourishing meals,’’ James

Playsted Wood reported in Magazines in the Twentieth Century. It

included suggested menus for families with adequate as well as for

those with meager and less-than-meager budgets. The first issue in

1934 offered menus for a family of four ranging from eleven to

thirteen dollars a week to five to six dollars a week. The April 30,

1934, sheet contained ‘‘menus especially adapted to the needs

of children.’’

The menu sheet was so successful and so expensive to produce

that two A&P executives, Frank Wheeler and Donald P. Hanson,

developed plans to make a women’s service magazine of it. A

subsidiary was founded, and in October 1937 the first 815,000 copies

of Woman’s Day were ready for sale for three cents in A&P grocery

stores. Six of the 32 pages were devoted to recipes and menus. Other

pages included advertising for products chiefly found in the A&P, an

article that told ‘‘What to Do about Worry,’’ and another that asked,

‘‘Is Football Worthwhile?’’ From its beginning, the magazine con-

tained how-to-do-it articles, expanded in 1947 to a complete how-to

section, ‘‘How to Make It—How to Do It—How to Fix It.’’ By 1940

the magazine was able to guarantee advertisers a circulation of

1.5 million.

In 1943, Mabel Hill Souvaine began her fifteen-year tenure as

editor, and under her management the magazine grew in circulation to

nearly five million. By 1952, Woman’s Day was distributed in 4,500

A&P stores and, like its arch rival, Family Circle, was, as reported in

Business Week, ‘‘hard on the heels of the big women’s service

magazines.’’ In the 1950s, Woman’s Day told stores which dress

patterns it would feature and then told readers which stores stocked

fabrics appropriate for those patterns. In 1958, after a federal judge

dismissed a suit brought by several food companies that alleged the

magazine engaged in discriminatory practices that guaranteed it

advertising revenues, A&P sold Woman’s Day to the Fawcett Company.

Of the many store-distributed magazines founded in the 1930s,

Woman’s Day and Family Circle emerged as the hardiest and most

prosperous. With a readership of nearly 20 million in the late 1980s,

Woman’s Day was a close competitor to the ‘‘world’s largest wom-

en’s magazine,’’ Family Circle, which boasted a readership of more

than 21 million. By the 1990s, Woman’s Day continued to be one of

the most popular sources of information designed specifically for

women and their daily life.

—Erwin V. Johanningmeier

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Food-Store Magazines Hit the Big Time.’’ Business Week. No.

1171, February 9, 1952.

Taft, William H. American Magazines for the 1980s. New York,

Hasting House Publishers, 1982.

Wood, James Playsted. Magazines in the United States. New York,

Ronald Press, 1956.

Woodward, Helen. The Lady Persuaders. New York, Ivan

Obolensky, 1960.

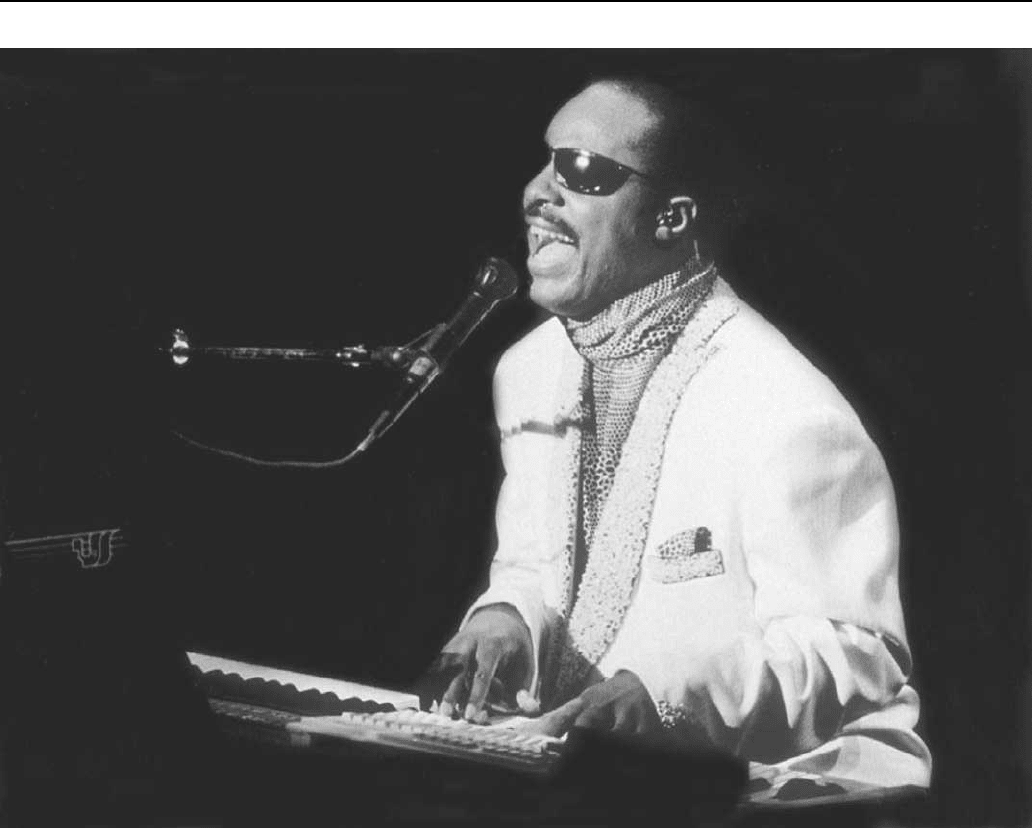

Wonder, Stevie (1950—)

In the 1970s, as pop music fractured into a thousand competing

subgenres, Stevie Wonder blended pop, jazz, soul, rock, funk, and

reggae without trivializing or pastiching. As he grew from child

prodigy to music’s foremost ambassador, he topped the charts while

winning three consecutive Album of the Year Grammy awards. A

producer, arranger, composer, singer, and master of numerous instru-

ments, Wonder also did more than anyone to tame the synthesizer,

transforming it from special effect to musical instrument. Lyrically,

he addressed everything from social inequity to romance and heart-

break, from Plant Rights to the birth of his daughter; and topped it all

off with unrelenting good humor.

Born prematurely on May 13, 1950, Stevland Judkins (later

Stevland Morris) lost his sight while in a hospital incubator. From his

earliest years he demonstrated an aptitude for music, banging on

anything he could get his hands near until his family managed, despite

their poverty, to acquire some instruments for him to play. When he

was ten years old, a family friend introduced the boy to Motown

founder Berry Gordy, who promptly signed the youth he soon

renamed ‘‘Little Stevie Wonder.’’ In addition to performing and

recording, Wonder also took music lessons from Motown’s legendary

studio band, the Funk Brothers. Though two early singles flopped, the

boy’s exuberance and showmanship came through on a 1963 live

recording, ‘‘Fingertips Part Two,’’ that soon became a number one

single; the album, Recorded Live—The Twelve Year Old Genius, also

rose to number one, a first for Motown.

A couple of lean years followed before Wonder displayed an

ability to write his own songs: his 1965 composition ‘‘Uptight’’

became a major hit and Gordy, who usually discouraged artists from

writing their own material, assigned songwriters to help the budding

genius. Over the next few years, hits included ‘‘For Once in My

Life,’’ ‘‘I Was Made to Love Her,’’ and a cover of Bob Dylan’s

‘‘Blowin’ in the Wind’’ which marked Wonder’s (and Motown’s)

first take on social themes. Wonder’s ‘‘My Cherie Amour’’ was

recorded in 1966 but only saw release in 1969 as a ‘‘B’’ side; it proved

WONDER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

170

Stevie Wonder

Motown’s Quality Control department wrong when it soared up the

charts. As he grew, Wonder became increasingly disenchanted with

Motown’s assembly line approach to hit-making, though he had more

freedom than most of the label’s artists. He was allowed to start

producing some of his own music starting in 1968, and in 1970 won a

Best R&B (rhythm and blues) Producer Grammy for Signed, Sealed

& Delivered.

But in 1971, when he reached the age of majority and received a

ten-year backlog of royalties, he did not re-sign with the company.

Instead, he invested much of his fortune in new synthesizers and

devoted himself to recording at Electric Lady Studios, designed by

fellow sonic explorer Jimi Hendrix. Shocked that Wonder would

consider abandoning the Motown family, Gordy negotiated a new

contract that gave the artist unprecedented artistic freedom, including

his own music publishing company. Wonder responded with a run of

the most innovative, popular, and critically praised albums in Motown

history, starting with two albums in 1972: Music of My Mind and

Talking Book, which spawned two number one singles, the ballad

‘‘You Are the Sunshine of My Life’’ and the funk tune ‘‘Supersti-

tion.’’ The astonishing diversity of the material and the ear-opening

range of synthesized sounds (programmed by associate producers

Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil) were to become trademarks

of Wonder’s adult career. The following three albums, Innervisions,

Fulfillingness’ First Finale, and the double album Songs in the Key of

Life each won Album of the Year Grammies, and contained hit singles

like ‘‘Livin’ for the City,’’ ‘‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’,’’ ‘‘I Wish,’’

and ‘‘Sir Duke.’’ The combination of trenchant political lyrics set to

breathtaking melodies, unorthodox harmonies, and satisfying rhythms

set a high-water mark for pop music; his positive, engaging manner

kept the material from dragging the listener down.

Wonder was the foremost contributor to a trend in 1970s soul

music (also upheld by Earth, Wind & Fire, the Isley Brothers, and

War, among others) that shined a bright light on social problems but

always with spirituality, a constructive attitude, and musical innova-

tion. His do-it-yourself approach inspired a generation of artists who

wrote and produced their own material (Prince being the most

prominent example), and his unwillingness to take the easy way out

has resulted in a book of compositions frequently played and recorded

by top jazz musicians. Wonder’s easy good cheer refuted the stereo-

type of the troubled, harassed superstar.

After Songs, however, his fame began to fade. A 1979 soundtrack

to the film version of the bestselling non-fiction book The Secret Life