Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 5: U-Z

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WILLIAMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

141

Smith, Eric Lidell. Bert Williams: A Biography of the Pioneer Black

Comedian. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 1992.

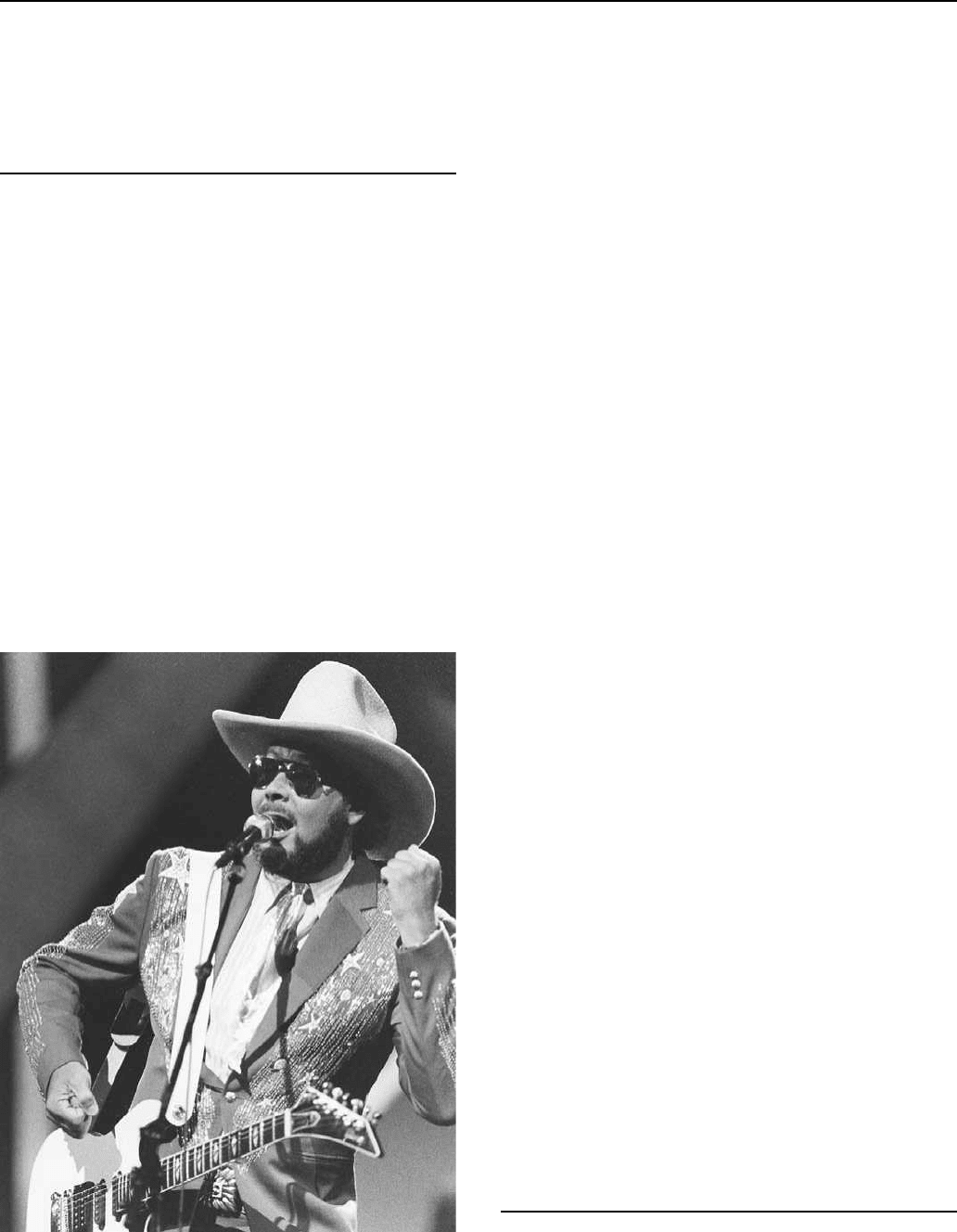

Williams, Hank, Jr. (1949—)

Perhaps no one has ever been simultaneously such a major star

and so much in the shadow of his father as Hank Williams, Jr. As an

eight-year-old, Williams began his career as an imitator of his

deceased father, then still the biggest name in country music. Ulti-

mately trading on the fact that his name made it impossible for the

country establishment to reject him, he was to become perhaps the

most significant force in bringing rock music into country.

In an industry that has never been ashamed of exploitation,

young Williams was shamelessly exploited. Between the ages of

eight and fourteen, he played fifty shows a year, singing his father’s

songs. By the time he was in his mid-teens, he was signed to MGM

Records, his father’s old label, and he was recording overdubbed

duets with his father; he even overdubbed the singing for George

Hamilton in Your Cheatin’ Heart, a movie biography of Hank, Sr.

By the time he was in his late teens, Williams was drinking

heavily; he felt utterly trapped inside a musical world that was making

less and less sense to him. He was listening to the rock and roll of his

generation—Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, and Elvis Presley—and

thinking about the kind of music he really wanted to play. At 23, with

his first marriage breaking up, Williams attempted suicide.

Hank Williams, Jr.

As part of his recovery, he left Nashville and moved to Alabama.

He began to work seriously on developing his own music. In August

1975, after finishing work on what was to be a landmark country rock

album, Hank Williams, Jr. and Friends, he took a vacation in

Montana, and suffered a devastating accident: a near-fatal fall down a

mountain virtually tore his face off.

After extensive physical therapy and plastic surgery to recon-

struct his face, Williams returned to music with an absolute determi-

nation to create his own, rock-oriented kind of sound. A new country

audience—one that had opened up to the ‘‘outlaw’’ sounds of Willie

Nelson and Waylon Jennings—was ready for him. After a few modest

successes, the highest-charting being his cover version of Bobby

Fuller’s ‘‘I Fought the Law,’’ he reached his stride in 1979 with a

song that looked back at the past at the same time it snarled with the

beat and attitude of rock. The song was ‘‘Family Tradition,’’ and it

was highly autobiographical. In it Williams was asked, ‘‘Why do you

drink, and why do you roll smoke, and why do you live out the songs

that Hank wrote?’’ Williams responded that he was simply carrying

on a family tradition.

This proved to be a winning formula for Williams. Many of his

subsequent hits were autobiographical. In one, he asks an operator to

put him through to Cloud Number Nine so he can talk to his father. In

‘‘All My Rowdy Friends Have Settled Down,’’ he remembers the

wildness of Nashville in the 1970s. Established as a major star in his

own right by the mid-1980s, he was able to use his preoccupation with

his father and his family history to successful record Hank Williams,

Sr., hits like ‘‘Honky Tonkin’.’’ In 1987, he even performed a duet

with his father on a newly discovered, never released recording of a

song called ‘‘There’s a Tear in My Beer.’’ Williams also released a

video duet, in which his image is inserted into an old kinescope of his

father. Since Williams, Sr. had never performed ‘‘There’s a Tear in

My Beer’’ for the cameras, a film was used in which he sings ‘‘Hey,

Good Lookin’’’ with his mouth electronically doctored to lip-synch

the words of the other song.

At the same time, Williams continued to be a major force in

bringing rock into country, and making it an important part of the new

country sound. In his semi-anthemic 1988 hit, ‘‘Young Country,’’ he

reminds his listeners that ‘‘We [the new generation of country

performers] like old Waylon, and we like Van Halen.’’ At the time,

this was still a significant statement, and one that it took a child of

traditional country like Williams to make. A few years later, the

rockers themselves had become the country music establishment,

with megastars like Garth Brooks modeling himself on arena rockers

like Journey.

As Williams himself settled into the role of middle-aged country

establishment figure in the 1990s, he remained solidly in the public

eye with his theme song for Monday Night Football.

—Tad Richards

F

URTHER READING:

Williams, Hank, Jr., with Michael Bane. Living Proof: An Autobiog-

raphy. New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1979.

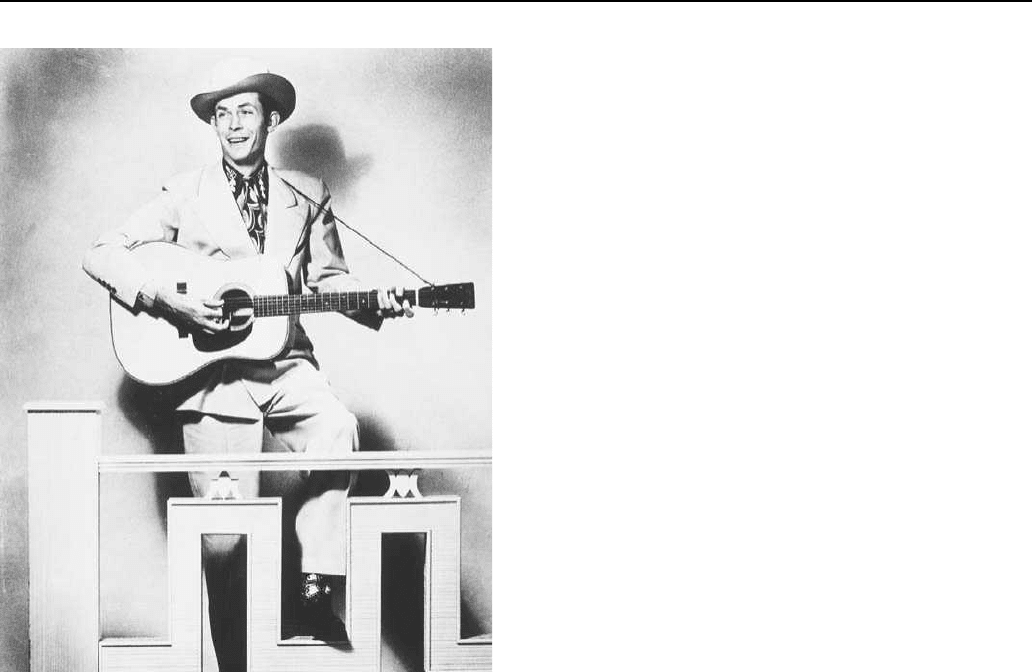

Williams, Hank, Sr. (1923-1953)

Widely acknowledged as the father of contemporary country

music, Hank Williams, Sr., was a superstar at the age of 25 and dead at

WILLIAMS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

142

Hank Williams, Sr.

29. Like Jimmie Rodgers, Williams had a short but highly influential

career in country music. Though he never learned to read or write

music, during his years of greatest commercial success, Williams

wrote and recorded over 100 polished, unique, and lasting songs,

releasing at least half a dozen hit records every year from 1949 until

1953. His direct, sincere, and emotional lyrics (‘‘Your cheatin’ heart /

Will make you weep / You’ll cry and cry / And try to sleep’’) set the

stage for much of the country music that followed, and many of his

songs, including ‘‘Cold, Cold Heart’’ and ‘‘Your Cheatin’ Heart,’’

have become classics.

His ability to transfix his audiences is the stuff of legend. Chet

Hagan’s Grand Ole Opry offers the following assessments: Little

Jimmy Dickens said that ‘‘You could hear a pin drop when Hank was

working. He just seemed to hypnotize those people. It was simplicity I

guess. He brought his people with him. He put himself on their level.’’

Minnie Pearl said, ‘‘He had a real animal magnetism. He destroyed

the women in the audience. And he was just as authentic as rain.’’ And

according to Mitch Miller (a Columbia Records executive), ‘‘He had

a way of reaching your guts and your head at the same time.’’

Williams had the unique ability to connect with his audiences,

comprised primarily of poor, white Southerners like himself, and,

particularly in the early days, fist-fights often broke out among his

female fans.

Born and raised in Alabama, Williams got a guitar at the age of

eight and learned to play and sing from a local blues street performer

known as ‘‘Tee Tot.’’ This early exposure to African-American blues

styles shaped his own musical character, forming a key element of

Williams’s trademark honky-tonk, country-blues sound. When he

was 12 years old, Williams won 15 dollars in a songwriting contest

with his ‘‘WPA Blues.’’ At the age of 14, Williams had organized his

own band and had begun playing locally for hoedowns, square

dances, and the like. In 1941, Williams and his band, the Drifting

Cowboys, began performing at a local radio station, most often

covering the songs of other country artists, including Williams’s hero,

Roy Acuff. Despite attempts to make a name for himself and his band,

Williams’s musical career stayed in a holding pattern for several years.

In 1946, Williams went to Nashville with his wife and manager,

Audrey, where a music publishing executive for Acuff-Rose Publish-

ing set up a recording session for Williams with Sterling Records. The

two singles he recorded then, ‘‘Never Again’’ (released in late 1946)

and ‘‘Honky Tonkin’’’ (released in early 1947) were quite successful,

rising to the top of the country music charts and breaking Williams’s

career out of its holding pattern. Williams signed the first exclusive

songwriter’s contract issued by Acuff-Rose Publishing, and he began

a long and productive songwriting partnership with Fred Rose, with

Williams writing the songs and Rose editing them.

In 1947, Williams won a contract with Metro Goldwyn Mayer

(MGM) Records. ‘‘Move It On Over,’’ Williams’s first MGM single,

was a big hit, and Williams and the Drifting Cowboys began appear-

ing regularly on KWKH Louisiana Hayride, a popular radio program.

Several other releases followed, and Williams became a huge country

music star. Already earning a reputation as a hard-drinking, womanizing

man, he had trouble being accepted by the country music establish-

ment, and Ernest Tubb’s attempts to get the Grand Ole Opry to sign

him on were initially rebuffed for fear that he would be too much

trouble. He was finally asked to join the Opry in 1949, and earned an

unprecedented six encores after singing the old country-blues stand-

ard ‘‘Lovesick Blues’’ at a 1949 Opry performance. Strings of hit

singles in 1949 and 1950 (including ‘‘Lovesick Blues,’’ ‘‘Mind Your

Own Business,’’ and ‘‘Wedding Bells’’ in 1949, and ‘‘Long Gone

Lonesome Blues,’’ ‘‘Moaning the Blues,’’ and ‘‘Why Don’t You

Love Me’’ in 1950) led to sell-out shows for Williams and the

reorganized Drifting Cowboys, earning Williams and the band over

$1,000 per performance. From 1949 through 1953, Williams scored

27 top ten hits. During this period, Williams began recording religious

material (both music and recitations) under the name Luke the Drifter,

and he managed to keep his drinking and womanizing in check.

In 1951, Tony Bennett had a hit single with a cover of Williams’

‘‘Cold, Cold Heart,’’ and other singers began recording (and having

hits) with Williams’s songs: Jo Stafford recorded ‘‘Jambalaya,’’

Rosemary Clooney sang ‘‘Half As Much,’’ and both Frankie Laine

and Jo Stafford covered ‘‘Hey Good Lookin’.’’ As a result, Williams

began to enjoy crossover success on the popular music charts,

appearing on the Perry Como television show, and touring as part of a

package group that included Bob Hope, Jack Benny, and Minnie

Pearl. Though not all of his hit records were his own compositions,

many of his best known works are ones he wrote, and many of them

seem to have an autobiographical bent.

Williams’s professional success, however, began to take a toll

on his private life. His long-time tendency to drink to excess became

full-blown alcoholism. Williams began showing up at concerts drunk

and abusive. As a result, he was fired from the Grand Ole Opry and

told to return when he was sober. Rather than taking the Opry’s action

as a wake-up call, Williams drank even more heavily. An accident

reinflamed an old back injury, and Williams began abusing the

morphine he was prescribed to deal with back pain. His marriage fell

apart, in part due to his drinking and drug abuse, and in part due to his

increasingly frequent dalliances with other women. In 1952, after

WILLIAMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

143

divorcing his first wife, Audrey, he quickly married a 19-year-old

divorcee named Billie Jean, selling tickets to what was billed as a

matinee ‘‘wedding rehearsal’’ and ‘‘actual wedding’’ that evening

(both were frauds; Billie Jean and Williams had been legally married

the previous day). Williams also came under the spell of a man calling

himself ‘‘Doctor’’ Toby Marshall (actually a paroled forger), who

often supplied him with prescriptions and shots for the sedative

chloral hydrate, which Marshall claimed was a pain reliever.

In December of 1952, Williams suffered a heart attack brought

on by ‘‘alcoholic cardiomyopathy’’ (heart disease due to excessive

drinking); found in the back seat of his car, he was rushed to the

hospital but was pronounced dead on January 1, 1953. His funeral,

held at a city auditorium in Montgomery, Alabama, was attended by

over 25,000 weeping fans. After his death, his record company

continued to issue a number of singles he had previously recorded,

including what is probably his most famous song, ‘‘Your Cheatin’

Heart.’’ These singles earned a great deal of money for his record

company and his estate, and artists as diverse as Johnny Cash and

Elvis Costello have made their own recordings of Williams’ songs in

recent years. Many of those associated with Williams attempted to

trade on his reputation after his death. Both of his wives went on tour,

performing as ‘‘Mrs. Hank Williams.’’ A supposedly biographical

film, Your Cheatin’ Heart, also exploited Williams’ fame and untime-

ly death. Williams’ children, Jett and Hank, Jr., went into country

music and have enjoyed some success (particularly Hank ‘‘Bocephus’’

Williams, Jr.). But it is Hank, Sr., who left his mark on country music.

Along with Jimmie Rodgers and Fred Rose, he was one of the first

inductees into Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame, elect-

ed in 1961.

—Deborah M. Mix

F

URTHER READING:

Hagan, Chet. Grand Ole Opry: The Complete Story of a Great

American Institution and Its Stars. New York, Holt, 1989.

Williams, Hank, Sr. The Complete Hank Williams. Polygram Rec-

ords, 1998.

Williams, Roger M. Sing a Sad Song: The Life of Hank Williams.

Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1981.

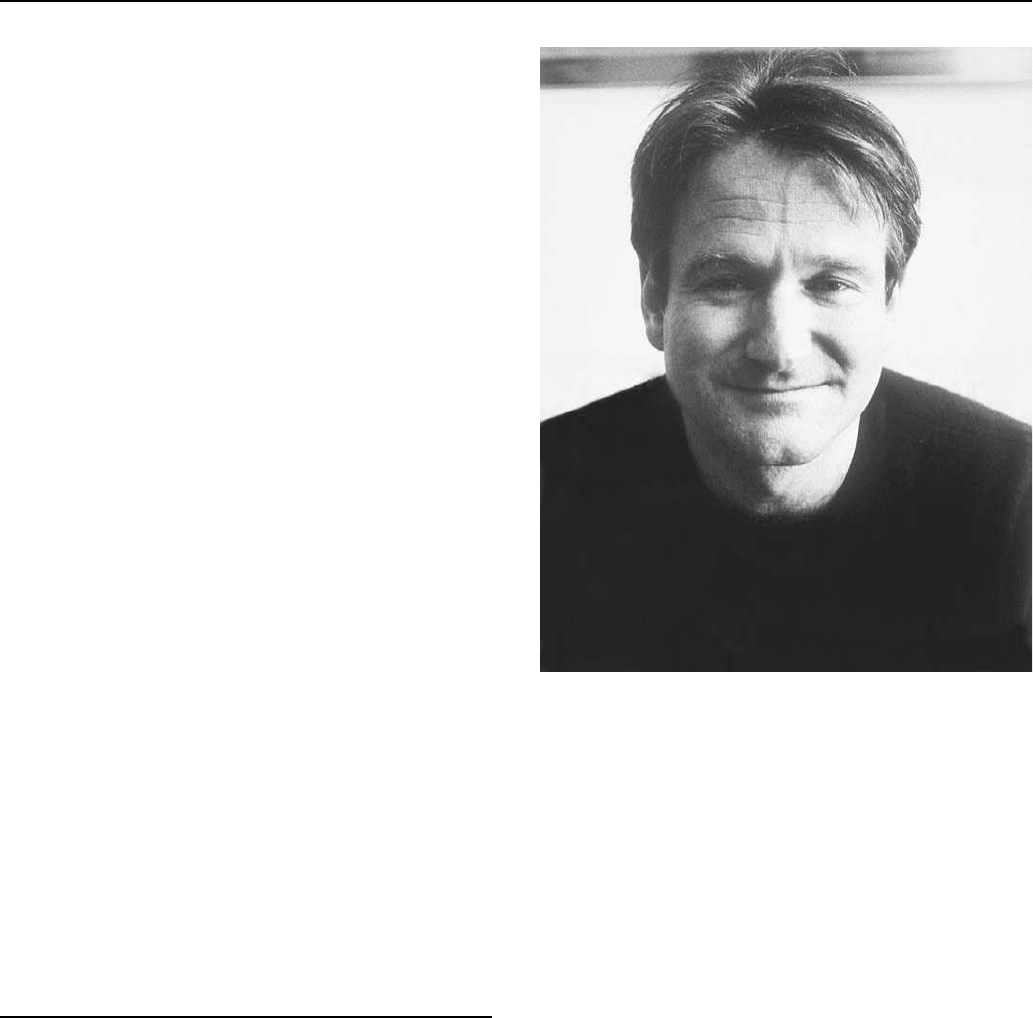

Williams, Robin (1952—)

With his manic versatility, comedic genius Robin Williams has

defined comedy for the last three decades of the twentieth century.

Whether expressing himself as a stand-up comic or an animated genie

or a cross-dressing nanny, he is without equal in the field of American

comedy. Much more than a comedian, however, some of his finest

work has been in dramatic film roles to which he has brought

humanity and warmth to a cast of characters ranging from a crazed

widower in The Fisher King (1991) to a sad but optimistic psychiatrist

in 1997’s Good Will Hunting, which garnered an Academy Award for

Best Supporting Actor.

Williams was born July 21, 1952, in Chicago, Illinois, to a father

who was a Ford company executive and a mother who was a former

model engaged in charity work. While both parents had sons by

previous marriages, Williams essentially grew up as an only child. In

interviews, he has described his childhood as lonely and himself as

Robin Williams

shy and chubby. His father was stern and distant, and his mother was

charming and busy. While Williams was close to his mother, she was

often absent, leaving him to roam their forty-room home for diver-

sion. He turned to humor as a way to attract attention. His interest in

comedy was aroused by hours spent in front of the television, and he

was particularly enthralled by late-night shows where he discovered

his idol, Jonathan Winters, another comic who consistently pushes

the envelope.

In 1967 Williams’s family moved to Tiburon, an affluent suburb

of San Francisco. In the less inhibited atmosphere in California,

Williams blossomed. When his father steered him toward a career in

business, Williams rebelled. His innate comedic skills were honed in

college, but he chose to leave two schools without finishing. He then

entered the prestigious Juilliard School in New York on a scholarship,

where he roomed with actor Christopher Reeve, who remains a close

friend. While the other students found Williams’s off-the-wall antics

hilarious, his professors were unsure of how to handle such frenetic

humor. Leaving Juilliard without graduating, Williams returned to

California and appeared in comedy clubs such as the Improv and the

Comedy Store.

By the mid-1970s, Williams had guest-starred on several televi-

sion shows including Saturday Night Live, Laugh-In, and The Rich-

ard Pryor Show. In 1977, a guest appearance on Happy Days as the

alien Mork from the planet Ork propelled him to stardom. Williams

reportedly won the role of Mork by showing up at his audition in

rainbow suspenders and standing on his head when asked to sit like an

alien. The appearance was so successful that the character of Mork

was given his own show, Mork and Mindy (1978-1982), which

WILLIAMS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

144

costarred Pam Dawber as the earthling who took in the stranded alien.

In retrospect, it is inconceivable that anyone else could have played

Mork with his zany innocence. Each week, the television audience

discovered their own planet through Mork’s reports to Ork leader

Orson at show’s end. Even though the characters of Mork and Mindy

predictably fell in love and married, the birth of their first child was

anything but predictable: Jonathan Winters as Mearth, who aged

backward, was the surprising result of this intergalactic coupling.

Even though Williams had so much control over the content of the

show that it became known informally as ‘‘The Robin Williams

Show,’’ he often felt stifled by the confines of network television as a

medium. Williams said in a 1998 TV Guide interview that he found

salvation in his HBO specials that aired without censorship, giving

him freedom to expand as a comic and solidify his position as a top-

notch performer.

In 1980 Williams lent his talent to the big screen with Popeye,

based on the heavily muscled, spinach-eating sailor from the comic

strip of the same name. It was a disappointing debut. His performance

in The World According to Garp in 1982 was better received, but it

was evident that Williams’s vast talents were not being properly

utilized outside of television. He managed to hit his stride with

Moscow on the Hudson in 1984, playing a Russian defector. Perhaps

the character who came closest to his own personality was that of an

outrageous disc jockey in 1987’s Good Morning, Vietnam, a role

which earned him his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor.

Drawing on his cross-generational appeal, Williams has ap-

peared in a series of films aimed at family audiences, such as the role

of Peter Pan in Hook in 1991. Although it was criticized by certain

reviewers, the role allowed Williams to display his own split person-

ality—that of the child who never quite grew up in the body of an

adult burdened by the everyday cares of his world. Williams followed

Hook with a delightful performance as the voice of Batty Koda in the

animated environmental film FernGully . . . The Last Rain Forest, but

nowhere was the enormity of Williams’s comedic range more evident

than in Disney’s Aladdin in 1992. As Genie, he managed to steal the

show. Refusing to be confined by his large-chested blue blob of a

body, Williams’s Genie metamorphosed by turns into a Scotsman, a

dog, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Ed Sullivan, Groucho Marx, a waiter, a

rabbit, a dinosaur, William F. Buckley Jr., Robert De Niro, a

stewardess, a sheep, Pinocchio, Sebastian from The Little Mermaid,

Arsenio Hall, Walter Brennan, Ethel Merman, Rodney Dangerfield,

Jack Nicholson, and a one-man band. There was talk of an unheard-of

Academy Award nomination for Best Actor for the portrayal of an

animated character. Williams did, in fact, win a special Golden Globe

award for his vocal work in Aladdin.

Even though Toys (1992) received little attention, Williams

followed it up with the blockbuster Mrs. Doubtfire, in which he

played the estranged husband of Sally Field and cross-dressed as a

nanny in order to remain close to his three children. Jumanji (1995), a

saga of characters trapped inside a board game, demonstrated a darker

side to Williams. He finally came to terms with Disney and reprised

the role of the genie in the straight-to-video Aladdin and the King of

Thieves in 1996. Williams’s zany side was again much in evidence in

1997’s Flubber, a remake of the Disney classic The Absent Minded

Professor. Before Flubber, Williams had returned to adult comedy

with his uproarious portrayal of a gay father whose son is about to be

married in The Birdcage (1996).

While comedy is the milieu in which Williams excels, his

dramatic abilities have also won critical acclaim. He was nominated

for an Academy Award for his portrayal of John Keating, a teacher at

a conservative prep school who attempts to open the eyes of his

students to the world of poetry and dreams in Dead Poet’s Society in

1989. The role of Parry in The Fisher King (1991) introduced a side to

Williams that stunned audiences and critics alike. After Parry’s wife

is murdered in a random shooting at a restaurant, he descends into

insanity from which he only occasionally emerges to search for his

personal holy grail with the help of co-star Jeff Bridges. The role of

Dr. Malcolm Sayer, a dedicated physician who temporarily restores

life to catatonic patients, in Awakenings again demonstrated Wil-

liams’s enormous versatility. In 1997, Williams won his Academy

Award for Best Supporting Actor in the Matt Damon/Ben Affleck

film Good Will Hunting, leading Damon’s Will Hunting to awkward

acceptance of his own reality and mathematical genius. Williams

followed that success with back-to-back roles in What Dreams May

Come and Patch Adams in 1998. Afterward, he expressed a desire to

modify his busy schedule and perhaps return to a weekly series.

Personally, Williams has had highs and lows. As a young

performer, he was well-known for his heavy consumption of drugs

and alcohol. He was forced to reexamine his life when his friend and

fellow comic John Belushi died after spending an evening with

Williams in the pursuit of nirvana. Another setback occurred when his

first marriage fell apart amid tabloid reports that he had left his wife

for his son Zachery’s nanny. Williams insisted that the marriage was

over before he became involved with Marsha Gracos, whom he

subsequently married. Their wedding rings are engraved with wolves

to signify their intention to mate for life; they have two children:

Zelda and Cody. Along with friends Billy Crystal and Whoopi

Goldberg, Williams has labored diligently for ‘‘Comic Relief,’’ an

annual benefit for the homeless.

—Elizabeth Purdy

F

URTHER READING:

Corliss, Richard. ‘‘Aladdin’s Magic.’’ Time. November 9, 1992, 74.

David, Jay. The Life and Humor of Robin Williams: A Biography.

New York, William Morrow, 1999.

Dougan, Andy Y. Robin Williams. New York, Thunder’s Mouth

Press, 1998.

Weeks, Janet. ‘‘Face to Face with Robin Williams.’’ TV Guide.

November 14-20, 1998.

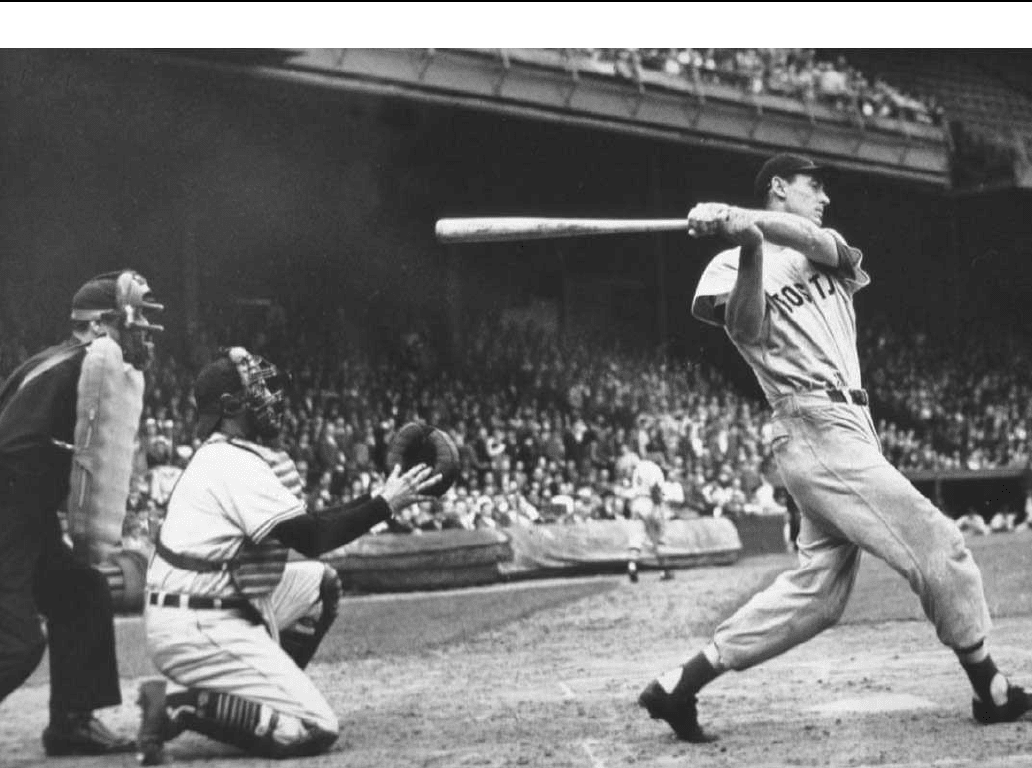

Williams, Ted (1918—)

Ted Williams, ‘‘The Splendid Splinter,’’ was one of the best

hitters of all time and is the last baseball player to hit over .400. His

scientific view of hitting changed the dynamics of the game forever.

But he was also probably the least celebrated modern-day baseball

hero. While he had the makings of stardom, he was unable to cultivate

the followings enjoyed by less talented but more amiable players,

such as his contemporary Joe DiMaggio.

On August 30, 1918, Theodore Samuel Williams was born in

San Diego, California, into a lower-middle class family. His parents

WILLIAMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

145

Ted Williams

worked constantly, leaving him plenty of time to play baseball. When

he was seventeen he signed with the hometown San Diego Padres.

But after only one year, he was sold to the Boston Red Sox.

Ted Williams proved himself immediately when he started for

the Red Sox in 1939. He led the league with 143 RBIs, the first rookie

to do so. In 1941, his batting average topped .400. Going into the last

day of the season, Williams’ average had been .39955, which in

baseball terms is a .400 batting average. Manager Joe Cronin gave his

star the option to sit out of the doubleheader, but he decided to play

and went six-for-eight, raising his batting average to an incredible

.406. His 1942 campaign earned him his first Triple Crown by hitting

.356, 137 RBIs, and 36 home runs. But even though he won the Triple

Crown, Williams did not win the MVP.

Williams interrupted his baseball career in 1943 to join World

War II, and he spent the next three years stateside as a pilot. When he

returned to baseball in 1946, the Red Sox had a talented postwar team

and Williams had another outstanding season, winning his first MVP.

Baseball also encountered ‘‘The Williams Shift’’ in 1946.

Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau pushed the infielders to the right

side of the field, trying to force the left-handed Williams to hit the ball

the opposite way, which he refused to do. That year Williams also led

Boston to their only World Series during his career, but the Red Sox

lost and Williams’ hitting was criticized by the media.

Williams’ relationship with the media, always tumultuous, turned

ugly after the 1946 season. The Boston press and many fans often felt

disenchanted with the temperamental superstar. Williams often went

public with his anger, liked to spit, never tipped his cap to the fans or

came out for curtain calls after home runs, and was candid about his

dislike of the Boston sports writers, who in turn criticized him in print.

Williams rebounded after the World Series, and in 1947 he won

his second Triple Crown but lost the MVP to Joe DiMaggio. He

closed the decade by winning the batting title in 1948 and winning his

second MVP in 1949, while leading the league in runs, walks, RBIs,

and hitting.

The 1950s were less kind to Williams. In 1950, he missed half

the season with a broken arm. In 1952 Williams was recalled to fight

in the Korean War, in which he survived a fiery plane crash. He came

back to baseball in 1954 and received two more batting titles in 1957

and in 1958, making him the oldest player in baseball history to do so.

A pinched nerve in his neck caused Williams to hit a career low .254

in 1959 and made fans and Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey push for his

retirement. But Williams came back to finish his career in 1960,

hitting .316 with 29 home runs, including one in his final at-bat.

Williams finished his baseball career with a .344 lifetime batting

average, the highest on-base percentage in history at .483, 521 home

runs, and the second highest slugging average at .634. The Sporting

WILLIAMS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

146

News named Ted Williams its ‘‘Player of the Decade’’ for the 1950s.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966.

Ted Williams had the stuff heroes were made of, even though his

contemporaries believed otherwise. He served his country in two

wars and was the most prolific hitter of his era. Williams changed the

face of baseball with his scientific approach to hitting and forcing

opposing managers to move their fielders. And today when any player

chases .400, Williams is the man to beat. In his autobiography, My

Turn at Bat, Williams states that when he walked down the street he

dreamed people would say, ‘‘There goes Ted Williams, the greatest

hitter who ever lived.’’ While a case could be made for such a claim,

Williams is less remembered than other more charismatic players.

But he did receive some belated recognition when the Ted Williams

Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame opened in Hernando, Flori-

da, in 1994.

—Nathan R. Meyer

F

URTHER READING:

Linn, Edward. Hitter: The Life and Turmoils of Ted Williams. San

Diego, Harcourt Brace, 1994.

Williams, Ted, with John Underwood. My Turn at Bat: The Story of

My Life. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Williams, Ted, with John Underwood. The Science of Hitting. New

York, Simon and Schuster, 1986.

Wolff, Rick. Ted Williams. New York, Chelsea House, 1993.

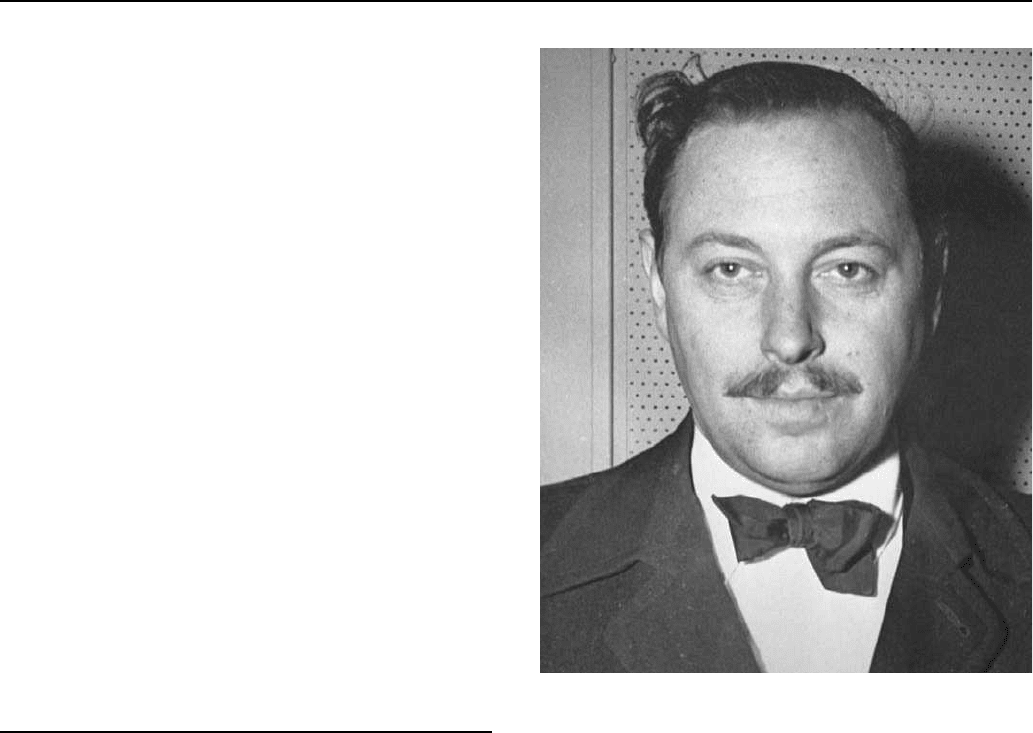

Williams, Tennessee (1911-1983)

An American playwright and screenwriter, Tennessee Williams

was regarded in his literary prime with an equal measure of esteem

and notoriety. After Eugene O’Neill, Williams was the first play-

wright to gain international respect for the emerging American

dramatic genre. Williams excelled at creating richly realized charac-

ters peppered with humor and poignancy. The ever-shifting autobiog-

raphy of Williams is equally renowned—always casual with fact, the

playwright shone in an era that adored celebrity and encouraged excess.

Tennessee Williams was born Thomas Lanier Williams on

March 26, 1911 in Columbus, Mississippi. His father, Cornelius

Coffin Williams, was a rough man with a fine Southern pedigree.

Absent for long periods of time, Cornelius moved his family from

town to town throughout Williams’ childhood. His mother, Edwina

Dakin Williams, imagined herself to be a Southern belle in her youth;

born in Ohio, Edwina insisted that her sickly young son focus on

Shakespeare over sports, and a writer was born.

The plays of Tennessee Williams deeply resonated with the

performing arts community of the 1940s. The complex characteriza-

tion and difficult subject matter of young Williams’ plays appealed to

a new generation of actors. The 1949 Broadway production of A

Streetcar Named Desire featured then-unknown actors Marlon Brando,

Jessica Tandy, and Karl Malden, trained in ‘‘Method Acting,’’ a new

model of acting experientially to project character psychology. Ac-

tors trained in the Method technique quickly discovered Williams was

writing plays that stripped bare an American culture of repression and

denial. A close-knit circle of performers, directors, and writers

immediately surrounded the temperamental Southern playwright.

Williams preferred certain personalities to be involved with his

Tennessee Williams

projects, including actors Montgomery Clift and Maureen Stapleton,

directors Elia Kazan and Stella Adler, and a cheerfully competi-

tive group of writers including Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, and

William Inge.

The 1950 film version of A Streetcar Named Desire brought

Williams and the actors instant fame. Lines from the film have

entered into the popular lexicon, from Blanche’s pitiful ironies (‘‘I

have always depended on the kindness of strangers’’) to Stanley’s

scream in the New Orleans night (‘‘Stella!’’). More than any other of

Williams’ screenplays, A Streetcar Named Desire’s lines resurface

today in the most unlikely places, from advertisements to television

sitcoms; the public often recognizes these phrases without having

seen the production at all.

Pairing misfortune and loneliness with gracefully lyrical speech,

Williams wrestles in his works with a repressed culture emerging

from Victorian mores. Social commentary is present in most works,

but the focus for Williams is the poetry of human interaction, with its

composite failings, hopes, and eccentricities. Early works were

bluntly political in nature, as in Me, Vashya!, whose villain is a

tyrannical munitions maker. After The Glass Menagerie, however,

Williams found he had a talent for creating real, vivid characters.

Often, figures in his plays struggle for identity and an awakened sense

of sensuality with little to show for the effort. Roles of victim and

victimizer are exchanged between intertwined couples, as with

Alexandra and Chance in Sweet Bird of Youth. The paralyzing fear of

mortality, so often an issue for his characters, plagues Mrs. Goforth of

The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop here Anymore. Most significantly,

perhaps, characters like Shannon of The Night of the Iguana, one of

WILLISENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

147

Williams’ late plays, sometimes find peace of spirit after they can lose

little else. Arthur Miller once declared Williams’ most enduring

theme to be ‘‘the romance of the lost yet sacred misfits, who exist in

order to remind us of our trampled instincts, our forsaken tenderness,

the holiness of the spirit of man.’’

The relationship between Williams’ work and popular culture is

long and varied. Many of his plays—The Glass Menagerie, A

Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Sweet Bird of Youth,

and Night of the Iguana—became major films of the 1950s and 1960s.

Williams’ films were immediately popular with mainstream audi-

ences despite their focus on the darker elements of American society,

including pedophilia, venereal disease, domestic violence, and rape.

Williams was one of the first American dramatists to introduce

problematic and challenging content on a broad level. Some of the

playwright’s subplots border on sensationalism, with scenes of im-

plied cannibalism and castration. Consequently, Tennessee Williams

had the curious distinction of being one of the most-censored writers

of the 1960s; Baby Doll, Suddenly Last Summer, and other films were

thoroughly revised by producers before general release. The modern

paradigm of film studios, celebrating fame while editing content, can

be seen in the choices made with Williams’ work, as Metro Goldwyn

Mayer produced his films and at the same time feared his subject

matter to be too provocative for audiences.

Tennessee Williams nurtured a public persona that gradually

shifted from shy to flamboyantly homosexual in an era reluctant to

accept gay men. Williams’ fears of audience backlash against his

personal life gradually proved groundless. Even late in life, however,

Williams was reluctant to assume the political agenda of others. Gay

Sunshine magazine declared in 1976 that the playwright had never

dealt openly with the politics of gay liberation, and Williams—

always adept with the press—immediately responded: ‘‘People so

wish to latch onto something didactic; I do not deal with the didactic,

ever . . . I wish to have a broad audience because the major thrust of

my work is not sexual orientation, it’s social. I’m not about to limit

myself to writing about gay people.’’ As is so often the case with

Williams, the statement is both true and untrue—his great, mid-career

plays focus upon relationships rather than politics, but the figure of

the gay male appears in characters explicit (Charlus in Camino Real)

and implicit (Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof) throughout his works.

As is noted in American Writers, Williams took a casual ap-

proach toward the hard facts of his life. In the early period of his fame,

Williams intrigued audiences by implying that characters like Tom

(read Thomas Lanier) in The Glass Menagerie represented his own

experiences. Elia Kazan, a director whose success was often linked to

Williams, promoted the Williams myth once by declaring that ‘‘eve-

rything in [Williams’] life is in his plays, and everything in his plays is

in his life.’’ Tennessee Williams’ connection with the outside world

was often one of gentrified deceit, beginning early as the Williams

family sought to hide his sister’s schizophrenia and eventual lobotomy.

In the closest blend of reality and art, the playwright’s attachment to

his sister, Rose Williams, has been well documented by Lyle Leverich

and others. The connection between Rose and Tennessee Williams

was profound, and images of her mental illness and sexual abuse often

surface in Williams’ most poignant characters. The rose rises as a

complex symbol in his plays, a flower indicative alternately of

strength, passion, and fragility.

The 1970s saw a gradual decline in Tennessee Williams’ artistic

skill, but he continued to tinker with the older plays and write new

works until his death. Williams was highly prolific, crafting over 40

plays, 30 screenplay adaptations of his work, eight collections of

fiction, and various books of poetry and essays. He won the Pulitzer

Prize twice, once in 1948 for A Streetcar Named Desire, and again in

1955 for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. His work continues to command

considerable social relevance—in 1998, a play on prison abuses, Not

About Nightingales, was staged in London for the first time.

—Ryan R. Sloan

F

URTHER READING:

Leithauser, Brad. ‘‘The Grand Dissembler: Sorting out the Life, and

Myth, of Tennessee Williams.’’ Time Magazine. Vol. 146, No. 22,

November 27, 1995.

Leverich, Lyle. Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams. 2 Vols. New

York, Crown, 1997.

Murphy, Brenda. Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collabora-

tion in the Theatre. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Phillips, Gene D. The Films of Tennessee Williams. Philadelphia, Art

Alliance Press, 1980.

Savran, David. Communists, Cowboys and Queers: The Politics of

Masculinity in the Work of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams.

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

Spoto, Donald. The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee

Williams. Boston, Little, Brown, 1985.

Unger, Leonard, editor. American Writers: A Collection of Literary

Biographies. 4 Vols. New York, Charles Scribner’s and Sons,

1960, 1974, 378-398.

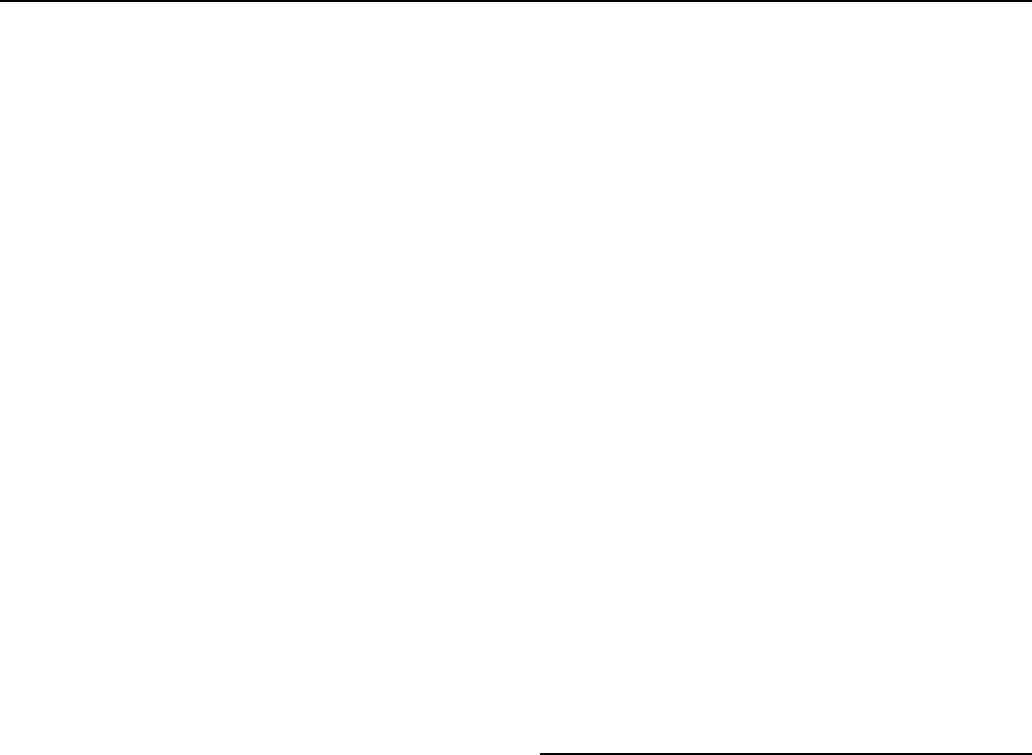

Willis, Bruce (1955—)

Bruce Willis first came to prominence as David Addison in the

mid-1980s television show Moonlighting. With its appealingly ec-

centric mix of throwaway detective plots and screwball romantic

comedy, the show was an ideal showcase for Willis’s often bemused

and often in control, wise-cracking action man. It seemed with his

first two films, Blind Date (1987) and Sunset (1988), both directed by

Blake Edwards, that Willis was going to follow the comedy route, but

after Die Hard (1988) Willis became instead one of the leading action

stars of the 1990s. Early attempts to break free of the John McClane

character and action man image met with failure and it is only since

Pulp Fiction (1994), perhaps, that Willis has been able to extend his

range, now alternating action with the occasional touch of character.

It is, however, easy to see why the Die Hard films succeeded, and how

Willis’s image was established through them.

Expertly directed by John McTiernan, the first Die Hard gave a

new boost to action films, the rough and ready American hero fighting

international terrorists in a disaster movie scenario leading to two

sequels, numerous imitations, and bringing stylish action and vio-

lence to the genre. And for his part, Willis seemed to embody a new

sort of action hero; in contrast to Rambo and the Terminator, John

McClane was a vulnerable family man. Up against high-tech crimi-

nals with nothing but his wits and a gun, he is brutally beaten and his

spirit is wearing thin. Of course, McClane wins the day, dispatching

the terrorist mastermind with his cowboy catchphrase, ‘‘Yippy kay

yay, mother fucker,’’ but he still has a few problems to face. The

skyscraper dynamics that recalled the film Towering Inferno were

followed up by the brutal airport action of Die Hard 2: Die Harder

BOB WILLS AND HIS TEXAS PLAYBOYS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

148

Bruce Willis

(1990). Another dose of realism is added to Die Hard with a

Vengeance (1995) in which McClane is divorced, alcoholic, and out

of shape.

An attempt in the early 1990s to extend his range in such films as

the Vietnam elegy, In Country (1989), did not altogether meet with

favorable reviews—in particular, playing the ‘‘English journalist’’ in

Brian De Palma’s misguided adaptation of Thomas Wolfe’s The

Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), then starring in his own expensive box-

office flop, Hudson Hawk (1991). Tony Scott’s The Last Boy Scout

(1991) only returned Willis to a more violent cop role; Robert

Zemeckis’s Death Becomes Her (1992) was an unfunny special

effects comedy; and Striking Distance (1993) was a minor action

film. In order to focus more attention on his acting rather than his

movie star status, Willis took on some quite interesting cameo roles:

as Dustin Hoffman’s gangster rival in Billy Bathgate (1991); along-

side his wife Demi Moore in Mortal Thoughts (1991); admirably

sending up his action man image in Robert Altman’s The Player

(1992); starring alongside Paul Newman in Nobody’s Fool (1994);

and acting as a comedy bunny in Rob Reiner’s otherwise uninterest-

ing family film, North (1994).

By all accounts, the so-called erotic thriller, Color of Night

(1994), is Willis’s worst film, but in the same year he was to launch a

more mature phase in his career as the boxer, Butch, in Quentin

Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. Taking his place amongst an ensemble cast

and latching onto Tarantino’s hip dialogue, Willis pared down his

usual smirks and steely stares, resulting in a notably different per-

formance that was all internal rage and insecurity. Terry Gilliam

managed to get an even more vulnerable performance out of Willis as

the confused time traveller in 12 Monkeys (1995); Walter Hill’s Last

Man Standing (1996) showcased Willis’s pared-down brutality, and

for their part The Fifth Element (1996) and Armageddon (1998)

ranged from glossy Die Hard action in the former to Willis saving the

world from pre-millennial excess in the latter. In between his big

action projects, however, Willis still managed to choose roles in such

small and unsatisfactory action films as The Jackal (1997) and

Mercury Rising (1998). Of the three owners of the Planet Hollywood

restaurant chain, however, Willis has clearly managed to become the

most accessible action hero of the 1990s, taking over from the

previous might of Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger and

cultivating an altogether more easygoing screen appeal.

—Stephen Keane

F

URTHER READING:

Parker, John. Bruce Willis: An Unauthorised Biography. London,

Virgin, 1997.

Quinlan, David. Quinlan’s Illustrated Directory of Film Stars. Lon-

don, Batsford, 1996.

Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys

Bob Wills pioneered ‘‘western swing,’’ an upbeat style of

country music that had a lasting impact on the industry. Wills, who

grew up in the cotton fields of northern Texas during the World War I

era, combined the blues of black sharecroppers with southern ‘‘hill-

billy’’ music. In the mid-1930s, Wills formed the Texas Playboys, a

band using experienced swing and Dixieland jazz musicians, who

toured throughout the southwest to packed houses. Western swing

became a national phenomenon after their 1940 hit ‘‘New San

Antonio Rose,’’ and Wills was inducted into the Country Music Hall

of Fame in 1968.

—Jeffrey W. Coker

F

URTHER READING:

Knowles, Ruth Sheldon. Bob Wills: Hubbin’ It. Nashville, Country

Music Foundation Press, 1995.

Malone, Bill C. Country Music USA. Revised edition. Austin, Univer-

sity of Texas Press, 1985.

Townsend, Charles R. San Antonio Rose: The Life and Music of Bob

Wills. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1986.

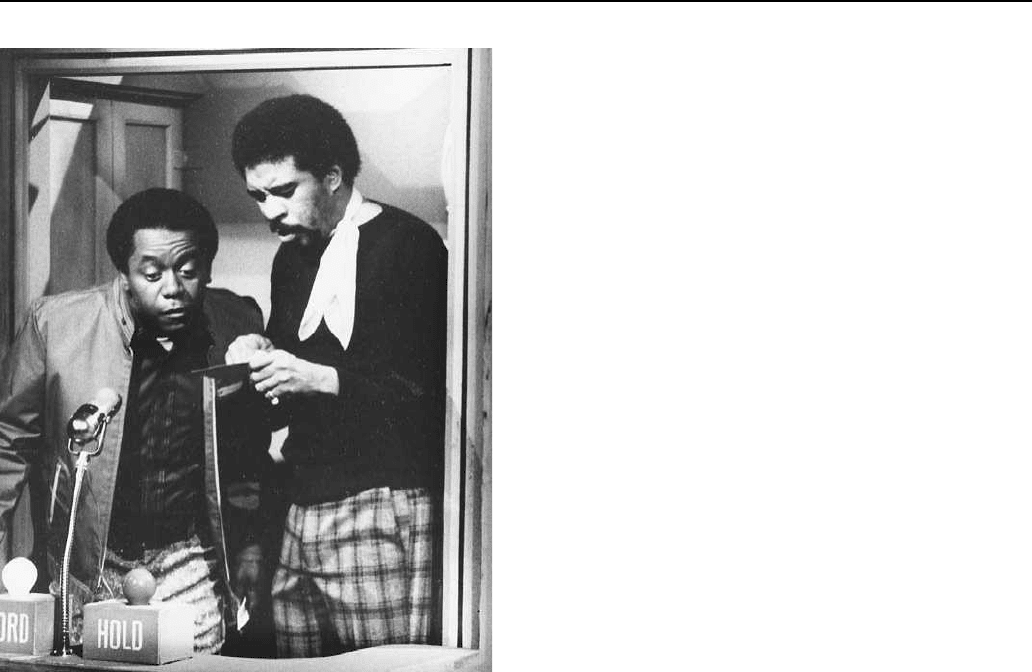

Wilson, Flip (1933-1998)

In the early 1970s, comedian Flip Wilson secured a place in

television history as the first African American to headline a success-

ful network variety series. Previous attempts by other black perform-

ers, such as Nat ‘‘King’’ Cole, Leslie Uggams, and Sammy Davis, Jr.,

WILSONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

149

Flip Wilson (left) with Richard Pryor on The Flip Wilson Show.

had all been ratings failures. From 1970 to 1974 The Flip Wilson

Show presented comedy skits, musical performances, and top Holly-

wood guest stars. The main attraction, however, was always Wilson

himself. He possessed a sharp and non-confrontational sense of

humor that appealed to a diverse audience. During its first two

seasons, his show was the second most popular program on television,

second only to All in the Family in the ratings. The most popular

aspect of the show was the large stable of stock characters portrayed

by Wilson each week. His most famous creation was the sassy and

liberated Geraldine Jones, who introduced the catch phrase ‘‘What

you see is what you get’’ into the American lexicon. Flip Wilson

proved that the mainstream American television audience could

accept a performer of color.

Clerow Wilson was born on December 8, 1933, in Jersey City,

New Jersey, and raised in extreme poverty as one of 18 children. He

grew up in a series of foster homes and left school at 16. During a

four-year hitch in the Air Force he traveled around the Pacific and

entertained his fellow enlisted men. Wilson acquired the nickname

‘‘Flip’’ from the troops, who appreciated his flippant sense of humor.

Upon being discharged from the service in 1954, he spent the next

decade touring across America, honing his act in small nightclubs.

His big break came during a 1965 appearance on The Tonight Show

Starring Johnny Carson, which led to frequent guest spots on The Ed

Sullivan Show, Laugh-In, and Love, American Style. In 1969, NBC

signed the comedian to host an hour-long variety show.

The debut episode of The Flip Wilson Show premiered on

September 17, 1970. Unlike other programs of the variety genre, it did

not feature chorus girls and large production numbers, but rather was

presented in a nightclub-like setting on a round stage surrounded by

an audience. Wilson welcomed established entertainment stars such

as John Wayne, Bing Crosby, Dean Martin, and Lucille Ball to the

show and introduced audiences to musical guests like Issac Hayes,

James Brown, and the Temptations. He continued the variety format

tradition of portraying several recurring characters on the program.

Among his most noteworthy personas were: Freddy the Playboy,

Sonny the White House janitor, Reverend LeRoy of the Church of

What’s Happening Now, and, of course, Geraldine Jones. Geraldine,

whom Wilson played in drag, became a national sensation as she

made wisecracks about her unseen, and very jealous, boyfriend

named ‘‘Killer.’’ Wilson commented on the miniskirted character’s

popularity, ‘‘The secret of my success with Geraldine is that she’s not

a putdown of women. She’s smart, she’s trustful, she’s loyal, she’s

sassy. Most drag impersonations are a drag. But women can like

Geraldine, men can like Geraldine, everyone can like Geraldine.’’

Along with Geraldine’s trademark line ‘‘What you see is what you

get,’’ Wilson popularized the phrases ‘‘The devil made me do it!’’

and ‘‘When you’re hot, you’re hot (and when you’re not, you’re

not!).’’ Although Wilson based many of his routines on ethnic humor

and black stereotypes, his humor was rarely overtly political. In 1971,

The Flip Wilson Show won Emmy Awards for Best Variety Series and

Best Writing for a Variety Series. The show was canceled in 1974 due

to strong competition from the CBS Depression-era drama The Waltons.

The second half of Wilson’s career was marked by a much

reduced public profile. He appeared in a few films, including Uptown

Saturday Night and The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh, and made

several television guest appearances. In the mid-1980s he returned to

television with two short-lived series: People Are Funny (1984), a

quiz show; and Charlie & Company (1985), a pale sitcom imitation of

The Cosby Show, in which singer Gladys Knight played his wife.

Wilson then retired from show business to raise his family. By the late

1990s, Wilson had again resurfaced due to the reruns of his 1970s

series on the TVLand cable network. Flip Wilson died on November

25, 1998, of liver cancer.

Like Bill Cosby on the television drama I Spy and Diahann

Carroll on the situation comedy Julia, Flip Wilson is regarded as a

breakthrough performer who helped destroy the color line on network

television in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He proved that white

audiences would accept a black comedian and embrace his humor.

His ability to employ racial humor without demeaning its targets gave

him the opportunity to reach the masses and provide network televi-

sion with a too-rare black perspective. In a TV Guide tribute shortly

after the comic’s death, Jay Leno wrote, ‘‘Flip was hip, but he made

sure everybody could understand him and laugh. That’s the sign of a

great performer.’’

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

Anderson, Christopher. The New Book of People. New York, G. P.

Putnam’s Sons, 1986.

Brooks, Tim. The Complete Directory to Prime Time TV Stars. New

York, Random House, 1987.

Leno, Jay. ‘‘Flip Wilson.’’ TV Guide. December 26, 1998, 9.

‘‘Flip Wilson - What You Saw Was What You Got.’’ CNN Interac-

tive. http://www.CNN.com. November 26, 1998.

WIMBLEDON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

150

Wimbledon

The world-renowned British tennis tournament, Wimbledon,

has become more than tradition, according to British journalist and

author John Barrett: more than ‘‘just the world’s most important and

historic tennis tournament,’’ having come to symbolize ‘‘all that is

best about sport, royal patronage, and social occasion that the British

do so well, a subtle blend that the rest of the world finds irresistible.’’

Held in late June and early July, Wimbledon is the only one of four

Grand Slam tennis events still played on natural grass.

The event started in 1877 as an amateur tournament called the

Lawn Tennis Championships hosted at the England Croquet and

Lawn Tennis Club (later renamed the All England Lawn Tennis

Club). The only event was men’s singles. Twenty-two players partici-

pated, and Spencer Gore won the final match, which spectators paid

one shilling to watch. The women’s singles event was instituted in

1884. Maud Watson claimed victory over a field of thirteen. Previous-

ly played at Oxford, the men’s doubles event was brought to Wimbledon

in 1883. Over the years, Wimbledon’s popularity continued to grow

steadily. By the mid-1880s, permanent stands were in place for the

crowds who were part of what Wimbledon historians refer to as the

‘‘Renshaw Rush,’’ coming to see the British twins Ernest and

William Renshaw win 13 titles between them in both singles and

doubles between 1881 and 1889.

By the turn of the century, Wimbledon had become an interna-

tional tournament. American May Sutton won the women’s singles

title in 1905 to become Wimbledon’s first overseas champion. About

this time, the royal family began its long association with Wimbledon

when the Prince of Wales and Princess Mary attended the 1907

tournament, and the Prince was named president of the club. In 1969,

the Duke of Kent assumed the duty of presenting the winning trophy.

Play at Wimbledon was suspended during World War I, but the

club survived on private donations. Tournament play resumed in

1919, with Suzanne Lenglen winning the women’s and Gerald

Patterson the men’s titles. In 1920, the club purchased property on

Church Road and built a 14,000-capacity stadium, which Wimbledon

historians credit with playing a critical role in popularizing the event.

World War II suspended play again, but the club remained open to

serve various war-related functions such as a decontamination unit

and fire and ambulance services. In 1940, a bomb struck Centre

Court, demolishing 1,200 seats. Although the tournament’s grounds

were not fully restored until 1949, play resumed in 1946, producing

men’s champion Yvon Petra and women’s champion Pauline Betz.

The expansion of air travel in the 1950s brought even more

international players to Wimbledon. This period also saw the domina-

tion of American players at the tournament, with such champions as

Jack Kramer, Ted Schroeder, Tony Trabert, Louise Brough, Maureen

Connolly, and Althea Gibson (the first African-American winner).

Australian players Lew Hoad, Neale Fraser, Rod Laver, Roy Emer-

son, and John Newcombe then dominated the men’s singles title from

1956 through the early 1970s.

In 1959, the club began considering a change in its amateur-only

policy in light of the increasing number of players receiving financial

assistance in excess of the limits set by the International Tennis

Federation. It was not until 1967, however, that the Lawn Tennis

Association voted to officially open the championship to both profes-

sionals and amateurs. At the first open tournament in 1968, Rod

Laver and Billie Jean King won the men’s and women’s singles

titles, respectively.

In 1977, Wimbledon celebrated its centenary anniversary. In

honor of the occasion, the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum was

opened at Wimbledon. 1984 marked the centenary of the women’s

singles event. The tournament now has five main events: men’s and

women’s singles, men’s and women’s doubles, and mixed doubles. It

also sponsors four events for juniors (18 and under) and invitation

events for former players. Each of the five main championships has a

special trophy. The women’s singles trophy, first presented by the All

England Club in 1886, is a silver parcel gilt tray made by Elkington

and Company in 1864. The men’s singles trophy is a silver gilt cup

and cover inscribed ‘‘The All England Lawn Tennis Club Single

Handed Champion of the World,’’ and was first presented by the All

England Club in 1887. The men’s doubles trophy is a silver challenge

cup, first presented in 1884. The women’s doubles trophy is a silver

cup and cover, known as ‘‘The Duchess of Kent Challenge Cup,’’ and

was first presented in 1949 by Her Royal Highness the Princess

Marina, then president of the All England Club.

Roughly 500 players currently compete at Wimbledon. To

participate, players have to submit an entry six weeks prior to the

tournament. A Committee of Management and a referee rank the

entries and place players into three categories: accepted, need to

qualify, and rejected. The committee then decides which ‘‘wild

cards’’ to include in the draw. Wild cards are players who do not have

a high enough international ranking to make the draw, but are

included by the committee on the basis of past performance at

Wimbledon or popularity with British spectators. A qualifying tour-

nament takes place a week before the championships at the Bank of

England Sports Club in Roehampton, and the winners in the finals of

this tournament qualify to play at Wimbledon. An exception is

players who, although they lose in the final round of the qualifying

tournament, are still selected to play. Dubbed the ‘‘lucky losers’’ by

tournament organizers, these players are chosen in order of their

international ranking to fill any vacancies that occur after the first

round of the draw.

To date, the youngest-ever male champion is Boris Becker of

Germany. In 1985, the 17-year-old won the men’s singles champion-

ship. In 1996, Swedish player Martina Hingis became the youngest

ever female champion at age 15. Other notable records include

American Martina Navratilova’s unprecedented six-year reign on

Centre Court as women’s singles champion, and her overall all-time

record of nine singles titles. Two men have won the men’s singles

tournament five consecutive times, although a century apart: Bjorn

Borg of Sweden (1976-1980), and William Renshaw (1881-1886)

of Britain.

—Courtney Bennett

F

URTHER READING:

Little, A. ‘‘The History of the Championships.’’ http://

www.wimbledon.com/news.nsf/allstatichtml/history.html.

December 1998.

Medlycott, James. 100 Years of the Wimbledon Tennis Champion-

ships. London and New York, Hamlyn, 1977.

Robertson, Max. Wimbledon, Centre Court of the Game. London,

British Broadcasting Corporation, 1981.

Wade, Virginia, with Jean Rafferty. Ladies of the Court: A Century of

Women at Wimbledon. New York, Atheneum, 1984.