Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 5: U-Z

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WHOENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

131

Marvelous for Words,’’ ‘‘On the Good Ship Lollipop’’), and after

Whiting died when Margaret was still a teenager, songwriter Johnny

Mercer became her mentor. Signed to Mercer’s Capitol label in the

early 1940s, she had 12 gold records before the rock ’n’ roll era,

including Mercer’s ‘‘My Ideal’’ and her signature song, ‘‘Moonlight

in Vermont.’’ One of the first singers to cross Nashville over into Tin

Pan Alley, she hit Number One with ‘‘Slippin’ Around,’’ a duet with

country star Jimmy Wakely.

A cabaret revival in the 1970s and 1980s gave Whiting a new

career as one of New York’s most beloved cabaret performers, on her

own and as part of a revue, 4 Girls 4, with Rosemary Clooney, Rose

Marie, and Helen O’Connell. She also starred in a tribute to Johnny

Mercer staged by her longtime companion, former gay porn star

Jack Wrangler.

—Tad Richards

F

URTHER READING:

Whiting, Margaret, and Will Holt. It Might As Well Be Spring: A

Musical Autobiography. New York, William Morrow, 1987.

The Who

Still regarded in the late 1990s as one of the greatest rock bands

of all time, the Who were bold innovators who changed the face of

popular music forever. Having planted the seeds of heavy metal, art

rock, punk, and electronica, the Who are almost without peer in their

range of influence upon subsequent music. The Who boasted a

dynamic singer and stage presence in Roger Daltrey, a powerful

virtuoso bassist in John Entwistle, and one of the world’s greatest

drummers in the frenetic Keith Moon. But the guiding genius of the

Who was guitarist and songwriter Pete Townshend, who wrote and

arranged each song, and recorded the guitar, bass, drums, and vocals

onto a demo before presenting it to the band to learn and perform.

Born in West London in 1945, Townshend attended Ealing Art

school, where he learned about Pop Art and the merging realms of

high and low culture. When he formed the Who, he found a suitable

audience for this background among a youth subculture called the

Mods, who wore Pop Art clothing and sought out stylish new music

and amphetamine-driven dance styles. The Who’s manager, Kit

Lambert, encouraged the band to adopt the Mod look and write

significant songs that would appeal to Mods. Their early hit, ‘‘Can’t

Explain’’ (1964) expressed adolescent frustration, followed by the

angst-ridden ‘‘My Generation’’ (1965), one of the great rock anthems

of the period.

The Who were most famous for outrageous stage performances.

Townshend specialized in ‘‘windmill’’ power chords, in which he

would swiftly swing his arm 360 degrees before striking a chord. The

Who often smashed their instruments at the end of a show, with

Townshend shoving his guitar through the amplifier and Moon

smashing through the drumskins and kicking over the entire drum set.

Despite their commercial success, the Who remained in debt until

1969 because of this expensive habit.

The Who released their first album, The Who Sing My Genera-

tion in 1965. Their next album, A Quick One (1967; renamed Happy

Jack in America) featured a miniature ‘‘rock opera’’ on side two, a

series of five songs narrating a tale of suburban infidelity. The Who

Sell Out (1968) satirized commercials, again revealing their interest

in Pop Art. Magic Bus (1968) was the best album of their early period

but offered no hint of the grandeur of their next project, a full-scale

rock opera. The double album Tommy (1969) told the story of a deaf,

dumb, and blind boy who, after a miracle cure, becomes a cult leader.

The album was influenced by Townshend’s involvement with his

guru, Meher Baba. If spirituality was an unexpected theme from the

author of teen frustration and masturbation, the music was an equally

bold advance, establishing Townshend as a versatile guitarist and

ambitious composer. Nevertheless, responses to Tommy were mixed,

partly due to the difficulty of following the story. Charges of

pretentiousness were frequent. The artistic audacity of Tommy left the

Who with a formidable dilemma—where do you go from here?

The Who followed up the rock opera with the raunchy, visceral

Live at Leeds (1970), but soon Townshend grew ambitious again,

formulating another opera, Lifehouse. Eventually the concept was

abandoned, and the better half of the songs written for the project

were released as Who’s Next (1971), which many regard as the

greatest rock album ever made. Among its highlights are ‘‘Behind

Blue Eyes,’’ ‘‘Teenage Wasteland,’’ and one of the greatest rock

songs of all time, ‘‘Won’t Get Fooled Again,’’ a masterpiece of

overwhelming power, featuring incredible performances by each

band member. Who’s Next made innovative use of synthesizers and

sequencers, anticipating electronic music, and it established the Who

as a major creative power in rock. The following year, Townshend

released a solo album, Who Came First, devoted to Meher Baba.

Townshend then embarked upon yet another opera, based on the

raw passions of youth rather than philosophical ideas. Quadrophenia

(1973) told the story of the Mods and their rival subculture, the

Rockers. The story was simpler than Tommy but still rather confusing.

However, the Who had grown musically since their first opera.

Townshend was a more sophisticated arranger and made greater use

of piano (played by himself) and horns (played by Entwistle).

Quadrophenia was regarded as Townshend’s masterpiece, the defini-

tive expression of adolescent angst, combining the ambitions of

Tommy with the virtuosity and emotional power of Who’s Next. Both

Tommy and Quadrophenia were made into movies, the former an

awkward musical starring Daltrey, the latter a gritty drama which

helps to explain the album’s plotline, as well as the cultural milieu in

which the Who developed. For most Americans, the movie version of

Quadrophenia is a prerequisite for understanding the album.

The triumph of Quadrophenia left the Who in the same quandary

that Tommy had: where do you go from here? They avoided the

question with Odds & Sods (1974), a mixture of singles, B-sides, and

leftovers from the Lifehouse project. For a hodgepodge, it was a fine

album. The Who by Numbers (1975) was quieter, with thoughtful,

introspective lyrics. Who Are You (1978) found the Who delivering

up-tempo rock again. The lengthy title song was a worthy follow-up

to ‘‘Won’t Get Fooled Again.’’ The entire album was reminiscent of

Who’s Next, packed with powerful songs, and again featuring innova-

tive use of synthesizers. Unfortunately, Keith Moon died shortly

afterwards from an overdose of anti-alcoholic medication.

Following this tragedy, Townshend withdrew to record the

fascinating Empty Glass (1981), his finest solo album. Moon was

replaced by Kenny Jones of the Small Faces, and the Who recorded

two albums, Face Dances (1981) and It’s Hard (1982), before

breaking up. Then came countless collections of rarities, outtakes, B-

sides, demo tapes, etc., testifying to the Who’s enduring popularity,

although respect for the group was compromised by the weakness of

WHOLE EARTH CATALOGUE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

132

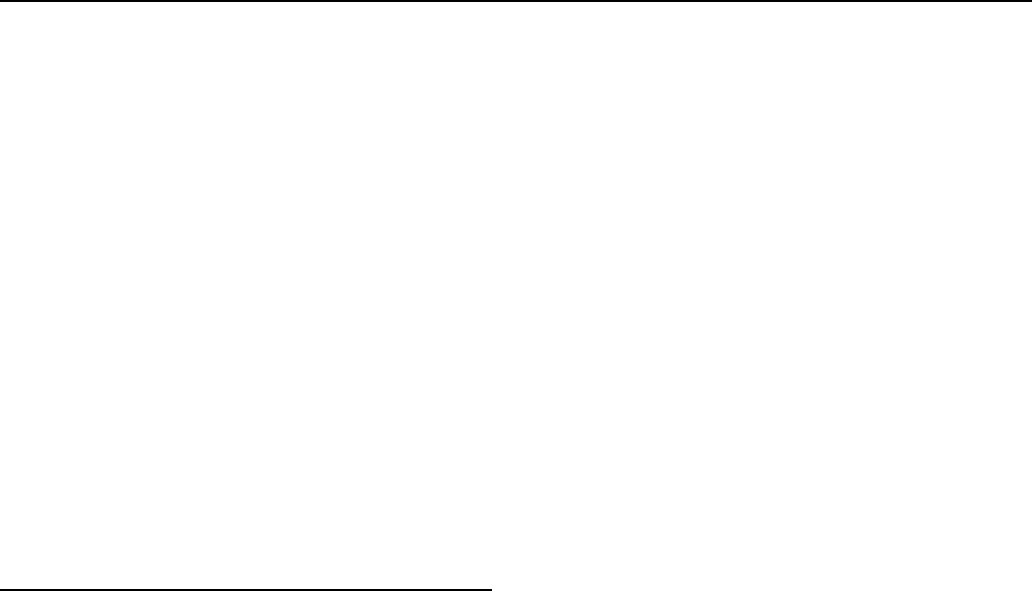

Members of the Who (l-r) John Entwistle, Roger Daltry, Pete Townshend, and Keith Moon

the post-Moon albums and by various anticlimactic reunions in the

1980s and 1990s. Townshend remained prolific as a solo artist but

tended to rely overmuch on concept albums. He published a book of

short stories, Horse’s Neck, in 1985.

—Douglas Cooke

F

URTHER READING:

Barnes, Richard. The Who: Maximum R & B. London, Eel Pie, 1982.

The Whole Earth Catalogue

First published in 1968 by Stewart Brand, The Whole Earth

Catalogue introduced Americans to green consumerism and quickly

became the unofficial handbook of the 1960s counter-culture. Winner

of the National Book Award and a national best-seller, TWEC

contained philosophical ideas based in science, holistic living, and

metaphysics as well as listings of products that functioned within

these confines. As many Americans sought to turn their backs on

America’s culture of consumption, TWEC offered an alternative

paradigm based in values extending across the counterculture.

TWEC combined the best qualities of the Farmer’s Almanac and

a Sears catalog, merging wisdom and consumption with environmen-

tal activism and expression. The first page declared that ‘‘the estab-

lishment’’ had failed and that TWEC aimed to supply tools to help an

individual ‘‘conduct his own education, find his own inspiration,

shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is

interested.’’ The text offered advice about organic gardening, mas-

sage, meditation, or do-it-yourself burial: ‘‘Human bodies are an

organic part of the whole earth and at death must return to the ongoing

stream of life.’’ Many Americans found the resources and rationale

within TWEC to live as rebels against the American establishment.

Interestingly, Brand did not urge readers to reject consumption

altogether. TWEC helped to create the consumptive niche known as

green consumerism, which seeks to resist products contributing to or

deriving from waste or abuse of resources, applications of intrusive

technologies, or use of non-natural raw materials. TWEC sought to

appeal to this niche by offering products such as recycled paper and

the rationale for its use. As the trend-setting publication of green

WILD BUNCHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

133

consumption, TWEC is viewed by many Americans as having start-

ed the movement toward whole grains, healthy living, and the

environmentally friendly products that continue to make up a signifi-

cant portion of all consumer goods. Entire national chains have based

themselves around the sale of such goods.

Even though green culture has infiltrated society, Whole Earth

continues in the late 1990s as a network of experts who gather

information and tools in order to live a better life and, for some, to

construct ‘‘practical utopias.’’ The Millennium Whole Earth Catalog,

for instance, claims to integrate the best ideas of the past twenty-five

years with the best for the next, based on TWEC standards such as

environmental restoration, community-building, whole systems think-

ing, and medical self-care.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Anderson, Terry H. The Movement and the Sixties. New York, Oxford

University Press, 1995.

The Millennium Whole Earth Catalog. San Francisco, Harper, 1998.

Wide World of Sports

‘‘The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat’’ became one of

the most familiar slogans on television for the American Broadcast

Company (ABC) sports show that lived up to its title. Beginning as a

summer replacement in 1961, Wide World of Sports endured into the

1990s, making a household name of original host Jim McKay and

launching the domination of ABC in sports and the rise of future ABC

Sports and News president Roone Arledge.

Arledge came up with the concept of packaging various sports

under this umbrella title and sent Jim McKay to anchor live coverage

of two venerable track meets—the Drake Relays from Des Moines,

Iowa, and the Penn Relays from Philadelphia—for the inaugural

broadcast of the program, on April 29, 1961. Wide World of Sports

survived its initial 13 weeks and returned every year as a 90-minute

program on Saturday afternoons beginning in January, and often

expanding to Sundays as well. The opening narration became famous:

‘‘Spanning the world to give you the constant variety of sports. The

thrill of victory and the agony of defeat, the human drama of athletic

competition. This is ABC’s Wide World of Sports.’’

Early on, Wide World of Sports covered many sports that later

became separate live broadcast institutions—tennis’s Wimbledon,

golf’s British Open, soccer’s World Cup. But Wide World made its

name with ‘‘nontraditional’’ sports, such as auto racing, boxing,

swimming, diving, track and field, gymnastics, and figure skating.

The particularly daring and unusual sports drew the most fans:

surfing, bodybuilding, World’s Strongest Man competitions, lumber-

jack contests, cliff divers from Acapulco, the Calgary Stampede

rodeo, and most notably, stunt motorcyclist Evel Knievel. Knievel

dominated shows of the early 1970s jumping barrels, cars, and busses

and nearly making it across the Snake River Canyon on his motorcy-

cle (and by rocket), breaking numerous bones in the process.

The program provided ABC Sports with sports coverage experi-

ence that it utilized to cover the Olympics. Wide World truly traveled

the globe, covering events in Europe and Asia, even Cuba and China.

Many of the events were carried live via satellite. The program also

developed the style that made Americans sit still and watch unfamiliar

sports and foreign performers such as Russian gymnast Olga Korbut,

Brazilian soccer star Pele, or Russian weightlifter Vasily Alekseev.

The ‘‘up close and personal’’ features emphasizing the life stories of

the athletes grew out Wide World of Sports and revolutionized sports

coverage. After Wide World, sports coverage became storytelling

rather than simply showing games and scores. The success of the

Olympics propelled ABC out of its low ratings status into a respect-

able television network and Roone Arledge into a position as the head

of ABC Sports and ABC News.

During the 1970s, Wide World of Sports became a brand name,

and its most famous image was set: the ‘‘agony of defeat.’’ While the

‘‘thrill of victory’’ changed almost every year, ‘‘the agony of defeat’’

was forever symbolized by hapless Yugoslavian ski jumper, Vinko

Bogataj, whose spectacular wipeout was taped in 1970.

By the end of the 1980s, Wide World of Sports lost its promi-

nence, as cable network ESPN became a superior ratings grabber as

the ultimate sports show—24 hours a day of the type of sports

coverage that Wide World pioneered. ESPN’s rise was ironic, as it

was partly owned by ABC.

In the 1990s, McKay left the role of studio host to a succession of

other ABC Sports personalities including Al Michaels and Julie

Moran. On January 3, 1998, McKay declared that Wide World of

Sports was canceled; the hour-and-a-half of all sorts of sports was

replaced by a studio host introducing single event broadcasts such as

the Indy 500, horse racing’s Triple Crown, and the national and world

championships in figure skating.

—Michele Lellouche

F

URTHER READING:

The Best of ABC’s Wide World of Sports (three volumes). CBS/Fox

Video, 1990.

McKay, Jim. with Jim McPhee. The Real McKay: My Wide World of

Sports. New York, Dutton, 1998.

Sugar, Bert Randolph. Thrill of Victory: The Inside Story of ABC

Sports. New York, Hawthorn Books, 1978.

The Wild Bunch

The Wild Bunch (1969) was the definitive film, and only true

epic, by one of Hollywood’s greatest directors, Sam Peckinpah; and

when it came to movie violence, it set the bar higher than it had ever

been set before. Earlier Westerns had good guys and bad guys as

clearly demarcated as the sides in World War II, but The Wild Bunch

came out during the Vietnam War, and it better reflected that war in

both its complexity and carnage. Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde

(1967), which ended with its two protagonists being riddled by

bullets, was the first major Hollywood film to show graphic vio-

lence—to suggest that shooting someone had consequences, that it

was messy and painful—but nothing could have prepared 1960s

audiences for the hundreds of deaths, the wave after wave of unrelent-

ing carnage—shown in slow motion and freeze-frame sequences—

that climaxed The Wild Bunch. Seven years before the film premiered,

Peckinpah was deer hunting when he shot a buck and was struck by

the fact that the bullet going in was the size of a dime, yet the blood on

the snow was the size of a bowling ball. He concluded that was the

WILD BUNCH ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

134

way violence and death were, and that was what he wanted to put on

film. During filming, Peckinpah had the technicians lay thin slices of

raw steak across the bags of stage blood, so when they exploded it

looked like the bullets were ripping out of bodies mixed with blood

and chunks of flesh. ‘‘Listen,’’ Peckinpah said, ‘‘killing is no fun. I

was trying to show what the hell it’s like to get shot.’’ He believed

people would shun violence if he showed what violence was really like.

But violence in movies without flesh-and-blood characters (see

almost any slasher film) is meaningless. Fortunately, Peckinpah had

great characters, played by superb actors, in a strong story, acted out

before beautiful vistas gorgeously photographed. As the movie opens,

the audience sees a tiny band of soldiers riding into a small town, then

walking into the local railroad office, as scruffy, armed men flit back

and forth on the rooftops overhead. It looks as though the bad guys are

about to ambush the good guys, though the reverse is true. The

railroad office manager asks the lead soldier, Bishop Pike (William

Holden), ‘‘May I help you?’’ and Pike grabs the manager, pulls him

out of his chair, shoves him and another against the wall, and tells the

other soldiers, ‘‘If they move . . . kill ’em!’’ These aren’t really

soldiers at all, but the Wild Bunch in disguise, and the men on the roof

are bounty hunters, there to ambush the outlaws and collect the prices

A scene from the film The Wild Bunch, with (l to r) Ben Johnson, Warren Oates, William Holden, and Ernest Borgnine.

on their heads. Leading the bounty hunters is former Wild Bunch

member Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan)—whose feud with Pike stems

from the time they were busted by Pinkerton agents, with Thornton

being shot and captured and Pike running away. Realizing they’re

about to be ambushed, the Wild Bunch times its departure to coincide

with the passing of a parade of temperance marchers, and the resulting

carnage is fairly intense.

The gang escapes to Mexico with the bounty hunters in hot

pursuit. In the town of Agua Verde they cross paths with Mapache, a

ruthless general at war with revolutionary Pancho Villa who has been

oppressing the local natives, even murdering the father and stealing

the fiancée of the Wild Bunch’s one Mexican member, Angel. The

gang agrees to rob a military supply train loaded with munitions for

Mapache in exchange for gold, and the robbery itself is a slickly done

caper, a Western Topkapi! Worried about helping Mapache get more

guns, Angel agrees to participate if, instead of gold, he can take one

case of guns for the revolutionaries. But Mapache finds out, and when

the gang returns to Agua Verde to trade the arms for the gold,

Mapache keeps Angel. At the end, the remaining outlaws decide to

rescue Angel, and their fight against the soldiers provides the

climactic bloodshed.

WILD ONEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

135

More complex than it first appears, The Wild Bunch is ultimately

about redemption. Early in the film, Pike tells a gang member who

wants to kill another, ‘‘We’re gonna stick together, just like it used to

be. When you side with a man you stay with him, and if you can’t do

that you’re like some animal, you’re finished!—we’re finished!—all

of us!’’ Yet Pike betrays this code again and again. During the

original railroad office job, when Crazy Lee (Bo Hopkins) tells Pike

he’ll hold the hostages until Pike says different, Pike just leaves him

behind to die. This is brought home when Pike’s oldest friend, Sykes

(Edmund O’Brien), tells Pike that Crazy Lee is his grandson. When

another gang member is wounded and might slow them down, Pike

shoots him; even Sykes himself is expendable when he becomes

wounded. At first, Angel is abandoned to Mapache and his men, but

Pike has finally had enough, and, against impossible odds, he and the

rest of the Wild Bunch decide to redeem themselves. They go down in

a blaze of glory—and, joining the revolutionaries, the one remaining

gang member and the one remaining bounty hunter ride off to fight the

good fight.

—Bob Sullivan

F

URTHER READING:

Bliss, Michael. Justified Lives: Morality and Narrative in the Films of

Sam Peckinpah. Carbondale, Ill., Southern Illinois University

Press, 1993.

Fine, Marshall. Bloody Sam: The Life and Films of Sam Peckinpah.

New York, Donald I. Fine, 1991.

Seydor, Paul. Peckinpah: The Western Films: A Reconsideration.

Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Weddle, David. If They Move . . . Kill ’Em!: The Life and Times of

Sam Peckinpah. New York, Grove Press, 1994.

Wild Kingdom

The first television program to help Americans visualize distant

life and consider ways they might help, Wild Kingdom became a

crucial tool in the formation of America’s environmental conscious-

ness and particularly in the movement’s shift toward global concerns.

Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom has served as Americans’ window

to the exotic species of the natural world since the 1960s. In the

tradition of National Geographic, host Marlon Perkins traveled

throughout the world sending back images of danger and intrigue.

Perkins’s pursuit of animals in their natural surroundings contributed

to the interest in ‘‘eco tourism’’ in which the very wealthy now travel

to various portions of the world not to shoot big game but only to view

it. Wild Kingdom continues production and has spawned an entire

genre of television, particularly for young viewers.

—Brian Black

The Wild One

The camera looks down a stretch of straight country highway,

then in bold, white letters appears the following: ‘‘This is a shocking

story. It could never take place in most American towns—but it did in

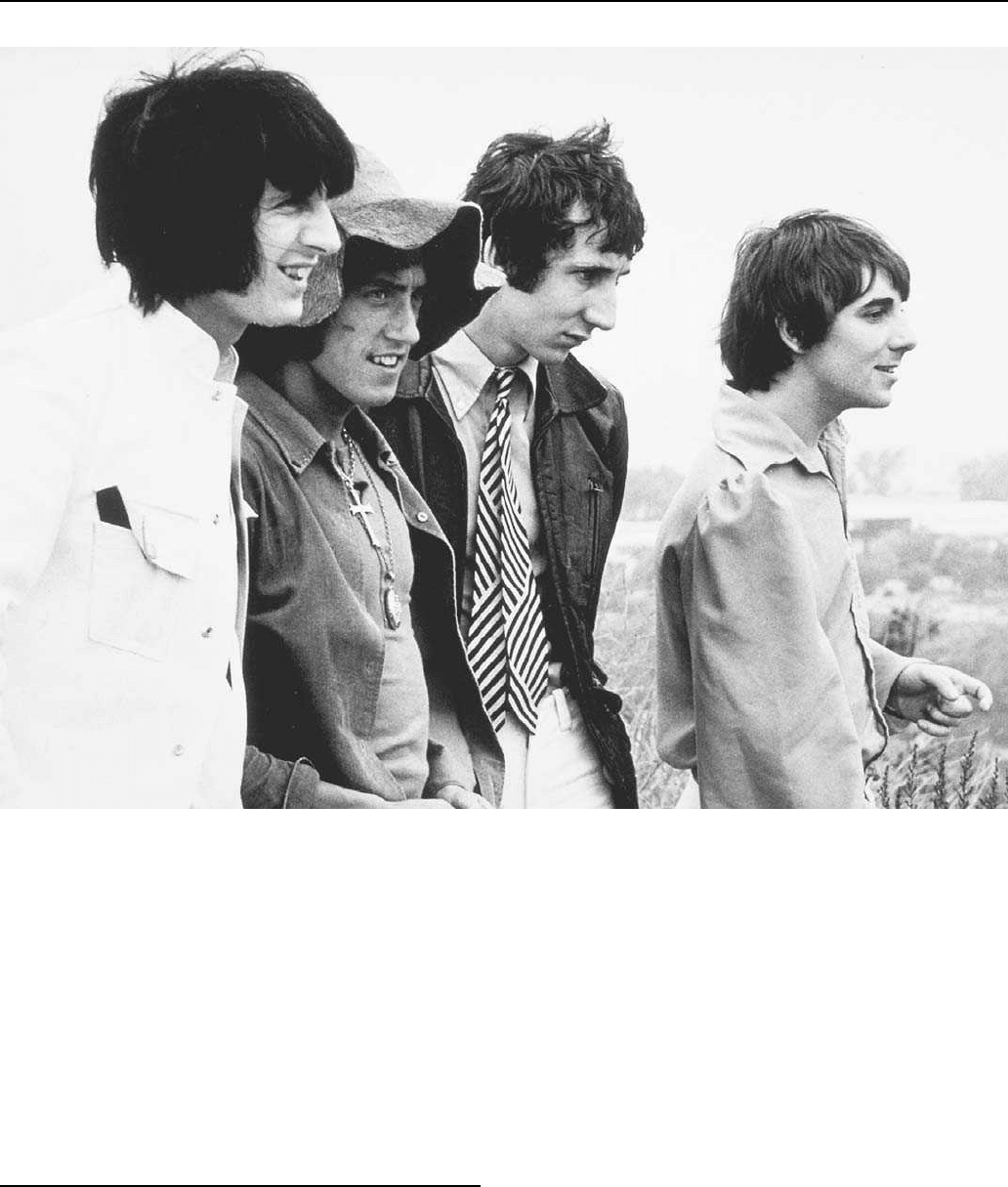

Marlon Brando in The Wild One.

this one. It is a public challenge not to let it happen again.’’ The words

fade away to be replaced by Marlon Brando’s voice speaking in a

southern drawl. ‘‘It begins for me on this road,’’ he says. ‘‘How the

whole mess happened I don’t know, but I know it couldn’t happen

again in a million years. Maybe I coulda stopped it early, but once the

trouble was on its way, I was just going with it.’’ A crowd of leather-

clad motorcyclists roar past the camera, and with the confident

declaration that what follows is an aberration, Stanley Kramer launched

The Wild One in 1954. The truth of the matter is somewhat more

complicated, for not only did the film incite a rash of copy-cat

behavior, but may have had an affect on the Hell’s Angels’ delecta-

tions a decade later.

The Wild One derives from a real riot, following a large

motorcycle rally in the Northern California town of Hollister. Ac-

cording to witnesses, six to eight thousand participants drag-raced up

and down the streets of Hollister; fist-fights, lewd behavior, and

vandalism were the norm, but the event was eventually dispatched by

29 policemen and it ended without a single loss of life. The coverage

in the July 1947 issue of Life magazine was sufficiently lurid and

alarmist, and it inspired Frank Rooney to turn the incident into a short

story, ‘‘The Cyclists’ Raid.’’ Rooney told the story from the point of

view of Joel Bleeker, a hotel manager (and significantly, a World War

II veteran) who witnesses his daughter’s death at the hands of the

cyclists. Bleeker views the motorcyclists as inhuman quasi-fascists,

but in its transition from story to film, sympathies were switched. The

hero became Johnny (Marlon Brando), leader of the Black Rebels

Motorcycle Club, who is sullen and incommunicative, but also

reserved and possessing a degree of chivalry lacking in his compatriots.

WILDER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

136

The rioting itself is transformed in typical Hollywood fashion

into a Manichean contest between Johnny and his dissipated rival,

Chino (Lee Marvin), who, to make matters perfectly clear, wears a

horizontal striped sweatshirt closely resembling prison garb. After

gratuitously interfering in a local motorcycle race, the bikers proceed

to the nearby town of Carbondale where they cause all manner of

havoc, prompted in part by the local saloon owner, who all but rubs

his hands in excitement at the prospect of a bar full of hard-drinking

motorcyclists. The tension between locals and bikers, already tense

after a notoriously bad driver hits one of the bikers, is further

exacerbated by the arrival of Chino and his cohorts. As the motorcy-

clists begin to run genuinely amuck, the town’s craven police officer

cowers in his office while his daughter, Kathy, is accosted by the

bikers, rescued by Johnny who drives off with her, and is thus absent

from the ensuing carnage. Nonetheless, as the leader he is blamed by

the townspeople, locked up, and when he escapes, knocked off his

motorcycle as he flees, accidentally killing an elderly man, and then is

unjustly accused of the killing.

Despite the rather thin story line—the New Yorker magazine

called it ‘‘a picture that tries to grasp an idea even though the reach

falls short’’—The Wild One was an instant hit with young audiences.

Theater owners throughout the country reported that teenage boys had

taken to dressing in leather jackets and boots like Marlon Brando and

accosting passersby. The pioneering members of the Hell’s Angels

(most of the group that later came to notoriety were children at the

time) identified deeply with Brando. ‘‘Whatta ya got?’’ was Brando’s

insouciant reply to the famous question, ‘‘Hey Johnny, what are you

rebelling against?’’ and it echoed in the real-life outlaws inchoate

dissatisfaction. ‘‘We went up to the Fox Theater on Market Street,’’ a

founding member told journalist Hunter S. Thompson. ‘‘There were

about fifty of us, with jugs of wine and our black leather jackets . . .

We sat up there in the balcony and smoked cigars and drank wine and

cheered like bastards. We could all see ourselves right there on the

screen. We were all Marlon Brando.’’

Much of the lasting allure of The Wild One stems from Brando’s

lionization by not only the Hell’s Angels, but by countless teenagers.

In ‘‘The Cyclists’ Raid,’’ Rooney had written: ‘‘They were all alike.

They were standardized figurines, seeking in each other a willful loss

of identity, dividing themselves equally among one another until

there was only a single mythical figure, unspeakably sterile and

furnishing the norm for hundreds of others.’’ In light of the Hell’s

Angels’ response to The Wild One as quoted above, and considering

the way Marlon Brando’s image was disseminated on posters, in

books, and turned into an archetype, it is no wonder many blamed The

Wild One for the Hell’s Angels’ excesses a decade later. Hollywood

gossip columnist Hedda Hopper blamed Kramer entirely for the

whole outlaw phenomenon, and Frank Rooney might well have

identified Marlon Brando as that ‘‘single mythical figure furnishing

the norm for hundreds of others.’’

It would be simplistic to blame the filmmaker and leading man

for a real life contagion, but the suspicion remains to this day. Perhaps

Hunter S. Thompson put it best when he wrote that the film ‘‘told a

story that was only beginning to happen and which was inevitably

influenced by the film. It gave the outlaws a lasting, romance-glazed

image of themselves, a coherent reflection that only a very few had

been able to find in a mirror, and it quickly became the bike-rider’s

answer to The Sun Also Rises.’’

—Michael Baers

F

URTHER READING:

Carey, Gary. Marlon Brando: The Only Contender. New York, St.

Martin’s Press, 1985.

Lewis, Jon. The Road to Romance and Ruin: Teen Films and Youth

Culture. New York, Routledge, 1992.

Pettigrew, Terence. Raising Hell: The Rebel in the Movies. New

York, St. Martin’s Press, 1986.

Rooney, Frank. ‘‘The Cyclists’ Raid.’’ Stories Into Film. Edited by

William Kittredge and Steven M. Krauzer. New York, Harper &

Row, 1979.

Shaw, Sam. Brando in the Camera Eye. New York, Exeter Books, 1979.

Spoto, Donald. Stanley Kramer, Filmmaker. New York, G.P. Putnam’s

Sons, 1978.

Thomas, Tony. The Films of Marlon Brando. Secaucus, New Jersey,

Citadel Press, 1973.

Thompson, Hunter S. Hell’s Angels, A Strange and Terrible Saga.

New York, Ballantine Book, 1966.

Wilder, Billy (1906—)

Born Samuel Wilder in an Austrian village, this six-time Acade-

my Award winning director, screenwriter, and producer was dubbed

Billy after Buffalo Bill of the 1880s traveling western show. That

American nickname apparently foretold, in the wake of the Nazi rise

to power, his 1934 emigration to Hollywood where he joined fellow

European exiles, learned English, and cultivated a legendary career

that indelibly marked American movie history. With partner Charles

Brackett, he co-wrote acclaimed comedies like Ball of Fire (1941),

then scripted, directed, and produced a string of hugely popular films,

including the quintessential film noir Double Indemnity (1944), and

The Lost Weekend (1945). Their alliance culminated with the savage

portrayal of Hollywood in Sunset Boulevard (1950). With I.A.L.

Diamond, Wilder created Some Like it Hot (1959) and The Apartment

(1960). His self-produced works more flagrantly expressed his cyni-

cism and penchant for vulgarity with Ace in the Hole (1951),

betraying a jaded sensibility ahead of its times.

—Elizabeth Haas

F

URTHER READING:

Lally, Kevin. Wilder Times: The Life of Billy Wilder. New York,

Henry Holt, 1996.

Sikov, Ed. On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder.

New York, Hyperion, 1998.

Zolotow, Maurice. Billy Wilder in Hollywood. New York,

Putnam, 1977.

Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1867-1957)

One of the best-known children’s authors, Laura Ingalls Wilder

wrote the popular, autobiographical ‘‘Little House’’ novels about her

WILDERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

137

late-nineteenth-century childhood on the American frontier. Pub-

lished in the 1930s and 1940s, these eight books were considered

classics of children’s literature by the 1950s and have appealed to

every succeeding generation of readers who thirsted for nostalgia.

The second of four daughters of Charles and Caroline Ingalls, a

post-Civil War American pioneering family, Wilder began writing in

childhood. Laura and her sisters penned poetry and compositions in

the many homes the Ingalls family built in the wilderness. Her writing

permitted her to have a voice, public and private, denied to many

nineteenth-century women and provided a way to release her frustra-

tions, disappointments, and enthusiasms during her life as pioneer,

teacher, wife, mother, farmer, businesswoman, and author. Wilder

continued her writing after she married her husband Almanzo in

1885. Keeping a travel diary of their 1894 trip to Mansfield, Missouri,

Wilder submitted it for publication to the De Smet News, where both

of her younger sisters worked as journalists. Distracted by farm duties

and volunteer work in her community, Wilder did not write seriously

until 1911 when she began preparing essays about farm life for the

Missouri Ruralist.

The fictional Laura was adventurous and inquisitive yet compli-

ant to the culture she lived in, obediently silencing herself and being

still to please her Pa. She was predictable, providing steadiness to her

readers. The real Laura craved such stability. Accustomed to econom-

ic and physical hardships, Wilder persevered despite her son’s death,

her husband’s disability from disease, conflicts with her strong-willed

daughter, crop failures and debt, and the misogyny and anti-

intellectualism of her patriarchal community. Ambitious and intelli-

gent, she ensured that the couple’s farm, Rocky Ridge, survived while

asserting her individuality. Known as Bessie to her family, she

became Laura Ingalls Wilder only in the last part of her life. This pen

name represented a professional woman whom few people actually

knew. The author Laura Ingalls Wilder answered fan mail, received

awards, and signed books, while Bessie Wilder was an ordinary

woman who performed her daily chores, read her Bible, attended club

meetings, supported the local library, visited with friends, and cared

for her ailing husband.

Wilder’s daughter, Rose, an accomplished writer, encouraged

her to write about her family’s adventures on the frontier. Wilder

completed her first attempt, Pioneer Girl, in 1930. In this novel, Laura

narrated her story from childhood to marriage, but no publisher was

interested. With Rose’s help, Wilder rewrote her manuscript to meet

literary expectations, dividing the novel into eight stories and present-

ing it in third person. Her publisher suggested that she make her

characters two years older than they really were to appeal to adoles-

cent readers. Although the books were presented as what Laura

remembered, the early stories about events during her infancy were

actually her parents’ memories. Originally titled When Grandma Was

a Little Girl, Wilder’s first book, Little House in the Big Woods, was

published in 1932 and was followed by Farmer Boy (1933), Little

House on the Prairie (1935), On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937), By

the Shores of Silver Lake (1939), The Long Winter (1940), Little Town

on the Prairie (1941), and These Happy Golden Years (1943). (A

manuscript for a story of Wilder’s early years of marriage was found

after her death. Edited by Roger Lea MacBride, The First Four Years

was published in 1971.) Critics and readers immediately accepted her

books, and the volumes sold well despite the Depression. The values

of home, love, and personal courage formed an image of rural serenity

that fulfilled readers’ need for comfort and a connection to a past that

they believed was simpler and happier than contemporary times.

Scholars noted the books’ archetypes: Pa was the dreamer and

provider, while Ma was the civilizer and stabilizer. Laura was a blend

of her parents. The Ingalls were praised for being spiritual, hard

working, and resourceful, enduring tragedy while constantly moving

in their covered wagon and homesteading virgin land. Aspects of

nineteenth-century American culture were provided through the

songs Pa sang, the items they purchased in stores, and the books and

magazines the women read. Scholars have criticized the patriarchal,

domestic, and materialistic messages of Wilder’s books and de-

nounced the characters’ racism toward Native Americans and minori-

ties. The women were often isolated and confined to homes, while

men were active participants with the outside world. Laura faced

conflicts between her need for individual freedom and expression,

and self-sacrifice and obedience for the good of her family.

Wilder stressed that she wrote her stories to provide history

lessons for new generations of children who no longer could experi-

ence the frontier and disappearing prairie that metaphorically offered

hope, prosperity, and renewal. In so doing, she sparked a cultural

phenomenon. Fans have dressed as Little House characters, collected

memorabilia, and visited Laura Ingalls Wilder heritage sites. The

Laura Ingalls Wilder-Rose Wilder Lane Home and Museum in

Mansfield, Missouri, houses many items, such as Pa’s fiddle, which

are featured in the books. Bookstores sell adaptations of Wilder’s

stories, including series about Ma’s and Roses’s childhoods. The

commercialization of Laura Ingalls Wilder has meant that fans can

buy Little House dolls, T-shirts, cookbooks, videos, diaries, and

calendars. Wilder’s books never have been out of print, and edited

versions of her periodical writing and letters are also available.

Foreign readers have also identified with Wilder’s universal themes;

her books have been published in 40 languages, and Internet sites

connect Wilder fans around the globe.

The American Library Association initiated the Laura Ingalls

Wilder Medal for accomplishments in children’s literature in 1954. A

television series, Little House on the Prairie (1974-1983), unrealisti-

cally portrayed Wilder’s life but was popular during an era when the

Bicentennial and Alex Haley’s book Roots revived Americans’

interest in the past. A Broadway musical, Prairie, ran in 1982, and a

Little House movie was in production in 1998.

—Elizabeth D. Schafer

F

URTHER READING:

Anderson, William T. Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography. New York,

HarperTrophy, 1995.

Miller, John E. Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman behind

the Legend. Columbia and London, University of Missouri

Press, 1998.

———. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town: Where History and

Literature Meet. Lawrence, University Press of Kansas, 1994.

Romines, Ann. Constructing the Little House: Gender, Culture, and

Laura Ingalls Wilder. Amherst, University of Massachusetts

Press, 1997.

Trosky, Susan M. and Donna Olendorf, editors. Contemporary Au-

thors. Vol. 137. Detroit, Gale Research, 1992.

WILDER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

138

Wilder, Thornton (1897-1975)

Thornton Wilder, with an enthusiasm for experimentation and

keen observation of human experience, enlivened the American

literary scene in the middle years of the twentieth century. He

received numerous awards, including the first Presidential Medal of

Freedom, and two Pulitzer Prizes for drama—Our Town (1938) and

The Skin of Our Teeth (1943). In 1927 he received his first Pulitzer

Prize for his novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1923), which

established his reputation as a leading novelist. One of his most

popular plays—The Matchmaker (1956)—became the mega-musical

Hello, Dolly, an international box office success. Gertrude Stein

became a close friend and influence during his last 12 years of major

work. In 1997, one hundred years after his birth, cultural festi-

vals throughout America celebrated the enormous talent of a man

whose command of the classics was so great he was nicknamed,

‘‘The Library.’’

—Joan Gajadhar

F

URTHER READING:

Burns, Edward, and Ulla Dydo. The Letters of Gertrude Stein and

Thornton Wilder. Edited by William Rice. New Haven, Yale

University Press, 1996.

Cunliffe, Marcus, The Literature of the United States. New York,

Viking Penguin, 1986.

Will, George F. (1941—)

Political commentator, columnist, and amateur baseball histori-

an, George F. Will is known for the way he imparts a conservative

spin to his opinions about the intersection of American culture and

politics in the closing years of the twentieth century. Best known for

his syndicated column in the Washington Post and for his regular

contributions to Newsweek, Will is also a frequent panelist on

televised political commentary programs, such as ABC’s This Week

with David Brinkley. As R. Emmett Tyrell Jr. wrote in his review of

The Leveling Wind: Politics, the Culture, and Other News, 1990-

1994, ‘‘George F. Will has always been a sober, civilized man with

serious political principles buttressed by wise historical thoughts.’’

Born in Champaign, Illinois, in 1941, George F. Will was

educated at Trinity College (B.A. 1962), Magdalene College of

Oxford University (B.A. 1964), and Princeton University (M.A.,

Ph.D. 1967). Several collections of Will’s newspaper and magazine

columns have been published including: Suddenly: The American

Idea Abroad and at Home, 1986-1990; The Morning After: American

Successes and Excesses, 1981-1986; The Pursuit of Virtue and Other

Tory Notions; and The Pursuit of Happiness, and Other Sobering

Thoughts. One of Will’s biggest crusades has been against big

government, notably as a supporter for term limitations for U.S.

Senators and Representatives. Reflective of public frustration with

the American political system during the 1980s and 1990s, Will

consistently pushed for term limits believing, as Peter Knupfer notes

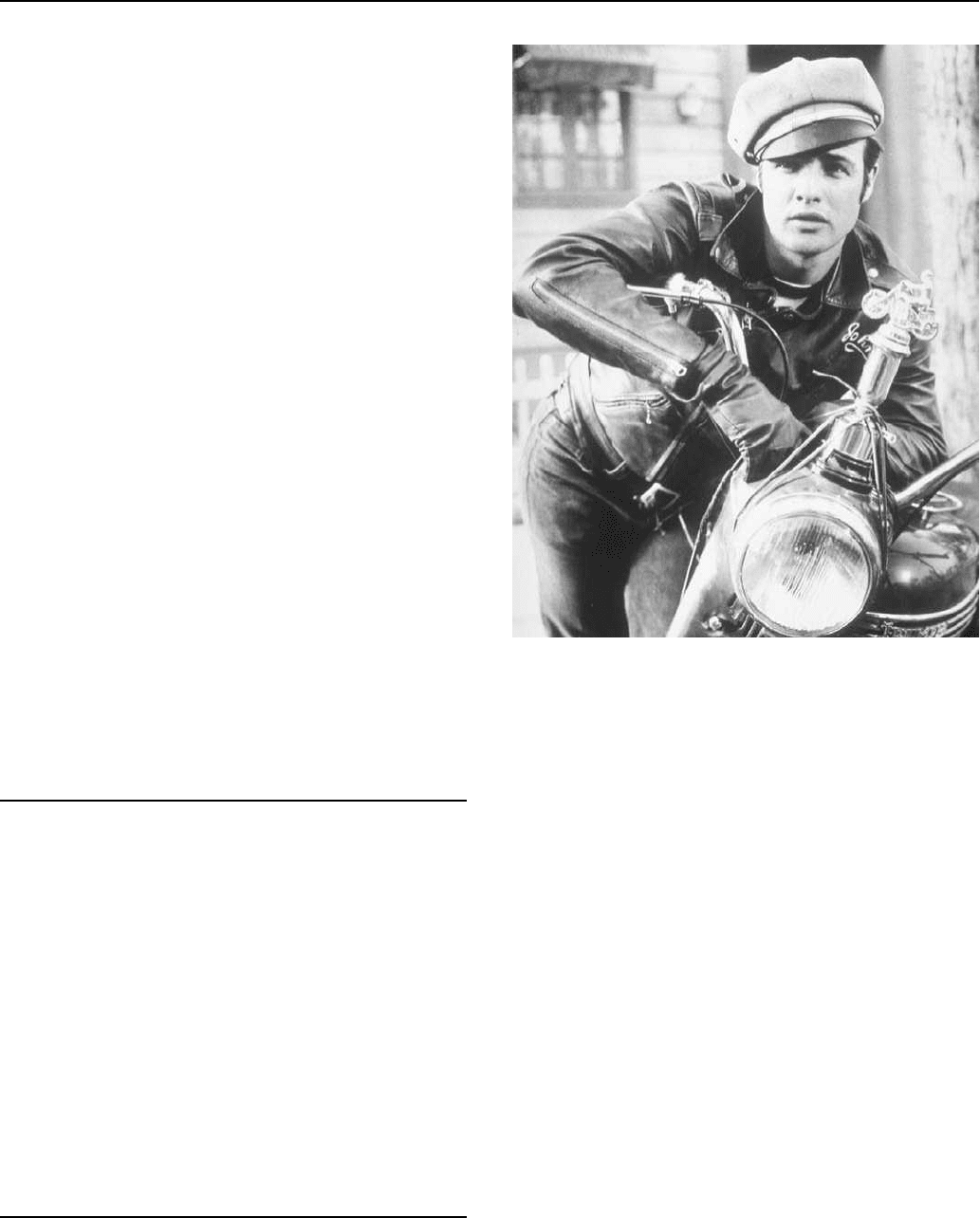

George F. Will

in the Journal of American History, these limits will ‘‘restore demo-

cratic institutions to deliberative processes and to leadership by

public-spirited amateurs’’ who are more interested in the public good

than in political careers. Will’s writings on term limits are found in

numerous columns and in one book, Restoration: Congress, Term

Limits, and the Recovery of Deliberative Democracy.

Although he generally adopts a conservative position, he is by no

means a typical Republican looking to either weaken government or

weaken the Democratic Party. As a self-styled conservative, Will

reshaped the way people viewed the spectrum of American political

thought by insisting that conservatives move away from narrow self-

interest toward an interest in the public good. Will’s thought urges

conservatives to reconsider their assumptions and adopt ideas steeped

in the ‘‘tradition of U.S. socio-political thought: the relation of

individuals to the larger community, the ways of nurturing a dynamic

democracy and the proper role of government,’’ in the words of

Marilyn Thie in America. From this position, Will wrote many

columns on what he saw as wasteful government spending, govern-

ment inefficiency, and political gridlock. Will came to believe one of

the biggest problems for American culture was the public’s heavy

reliance on—and demands on—its government. If the government is

misfiring in itself, then its ability to serve the public is highly

problematic, Will believed.

Beyond his primary focus on politics and American culture, Will

also wrote on a range of subjects that included pornography, journal-

istic ethics, advertising, the environment, and especially the game of

baseball. Relating the myths of American life, such as the American

WILLIAMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

139

dream and the great American pastime, to the realities of contempo-

rary American life remains one of Will’s contributions to cultural

discourse. Besides several columns for a variety of periodicals, his

book publications on the myths of American baseball include Bunts:

Curt Flood, Camden Yards, Pete Rose, and Other Reflections on

Baseball (1998) and Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball (1990).

—Randall McClure

F

URTHER READING:

Chappell, Larry W. George F. Will. New York, Twayne Publish-

ers, 1997.

Knupfer, Peter. ‘‘Review—Restoration: Congress, Term Limits, and

the Recovery of Deliberative Democracy by George F. Will.’’

Journal of American History. June 1994, 325.

Thie, Marilyn. ‘‘Suddenly: The American Idea Abroad and at Home,

1986-1990 by George F. Will.’’ America. June 8, 1991, 628-630.

Tyrell, R. Emmett, Jr. ‘‘Alone Again, Naturally—The Leveling Wind

by George F. Will.’’ National Review. January 23, 1995, 64.

Will, George F. Bunts: Curt Flood, Camden Yards, Pete Rose, and

Other Reflections on Baseball. New York, Scribner, 1998.

———. The Leveling Wind: Politics, the Culture, and Other News,

1990-1994. New York, Viking, 1994.

———. Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball. New York, Macmil-

lan, 1990.

———. The Morning After: American Successes and Excesses,

1981-1986. New York, Free Press, 1986.

———. The Pursuit of Happiness, and Other Sobering Thoughts.

New York, Harper & Row, 1978.

———. The Pursuit of Virtue and Other Tory Notions. New York,

Simon and Schuster, 1982.

———. Restoration: Congress, Term Limits, and the Recovery of

Deliberative Democracy. New York, Free Press, 1992.

———. Statecraft as Soulcraft: What Government Does. New York,

Simon and Schuster, 1983.

———. Suddenly: The American Idea Abroad and at Home, 1986-

1990. New York, Free Press, 1990.

———. The Woven Figure: Conservatism and America’s Fabric,

1994-1997. New York, Scribner, 1997.

Williams, Andy (1930—)

One of the great middle-of-the-road singers of the mid-twentieth

century, Andy Williams is among the very few whose popularity

survived the onset of rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s. Howard Andrew

Williams was born in the small town of Wall Lake, Iowa, the last of a

set of four brothers. The Williams Brothers formed a singing group

while Andy was still a child, and were regularly employed on radio

from 1938. The family relocated several times to facilitate the

Williams Brothers’ obtaining new radio contracts. At various times

they lived in Des Moines, Chicago, Cincinnati, and southern Califor-

nia. The two older brothers were drafted in the last days of World War

Two, and Andy Williams spent a comparatively calm period finishing

high school in Los Angeles.

In 1947 the foursome regrouped, joining with a new partner, Kay

Thompson. They played a wide variety of clubs over the next several

years, including a tour of Europe, before disbanding in 1953; the

brothers went their separate ways professionally. Andy Williams

landed a regular job on Steve Allen’s Tonight Show from 1954 to

1957, singing and taking part in Allen’s manic clowning, five nights a

week. The year 1957 saw Williams hosting a summer replacement

television program on NBC; he also had summer shows on ABC in

1958 and on CBS the following year. From 1962 to 1967, and again

from 1969 to 1971, Williams had his own highly successful series on

NBC. At various times his supporting cast included Dick Van Dyke,

Jonathan Winters, Ray Stevens, and the Osmond Brothers. His

program was noteworthy in that Williams was always willing to have

competing singers—major personalities such as Bobby Darin or

Robert Goulet—make guest appearances on his show.

Williams’ recording career, benefitting from his national expo-

sure on the Tonight Show, was a hit from the start. He recorded for the

Cadence label until 1962, when he switched to the larger Columbia

Records. His recording career had actually started much earlier,

however, in 1944, when he was picked to sing ‘‘Swingin’ on a Star’’

with Bing Crosby. Williams had several million-selling singles in the

1950s, including ‘‘The Village of St. Bernadette,’’ ‘‘Canadian Sun-

set,’’ and ‘‘The Hawaiian Wedding Song.’’ His version of ‘‘Butter-

fly’’ was the number-one record in America for three weeks in the

spring of 1957.

The song most closely identified with Williams, 1961’s ‘‘Moon

River,’’ was never a hit for him. However, it so perfectly suited his

smooth voice and mellow delivery that it became his signature song,

and served as his television theme from 1962 onwards. His populari-

zation of the Henry Mancini-written ‘‘Moon River’’ (from Breakfast

at Tiffany’s) was not lost on the composer; Andy Williams was

invited to sing the theme for the 1963 film Days of Wine and Roses,

another important Mancini work. Williams’ LP of the same name was

one of the six top-selling albums of 1963. Major hits were rare for

Williams after that year, his last being the theme from Love Story in

1971. His albums, television work, and live concerts all remained

quite successful.

Williams became a noted collector of art in the late 1950s. He

has built a well-regarded private collection of Impressionist and

modern paintings, located in his Manhattan home. In 1961 he married

a nineteen-year-old Folies-Bergère showgirl, Claudine Longet, whom

he met during her show’s stay in Las Vegas. Longet unsuccessfully

pursued careers in music and acting for years. The two separated in

1970, divorcing in 1975. The following year she fatally shot her long-

time lover, professional skier Spider Sabich, in their Colorado home.

Williams, who remained close to his ex-wife after the breakup of their

marriage, was publicly supportive of Longet throughout her trial and

the attendant media circus.

In addition to his highly rated variety program, which he ended

in 1971, Williams is known for hosting numerous seasonal television

specials. He is an avid golfer, and the host of the annual Andy

Williams Open golf tournament. In 1992 he opened his own theater in

Branson, Missouri, considered the second city of country music after

Nashville. Andy Williams’ Moon River Theatre there is one of the

WILLIAMS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

140

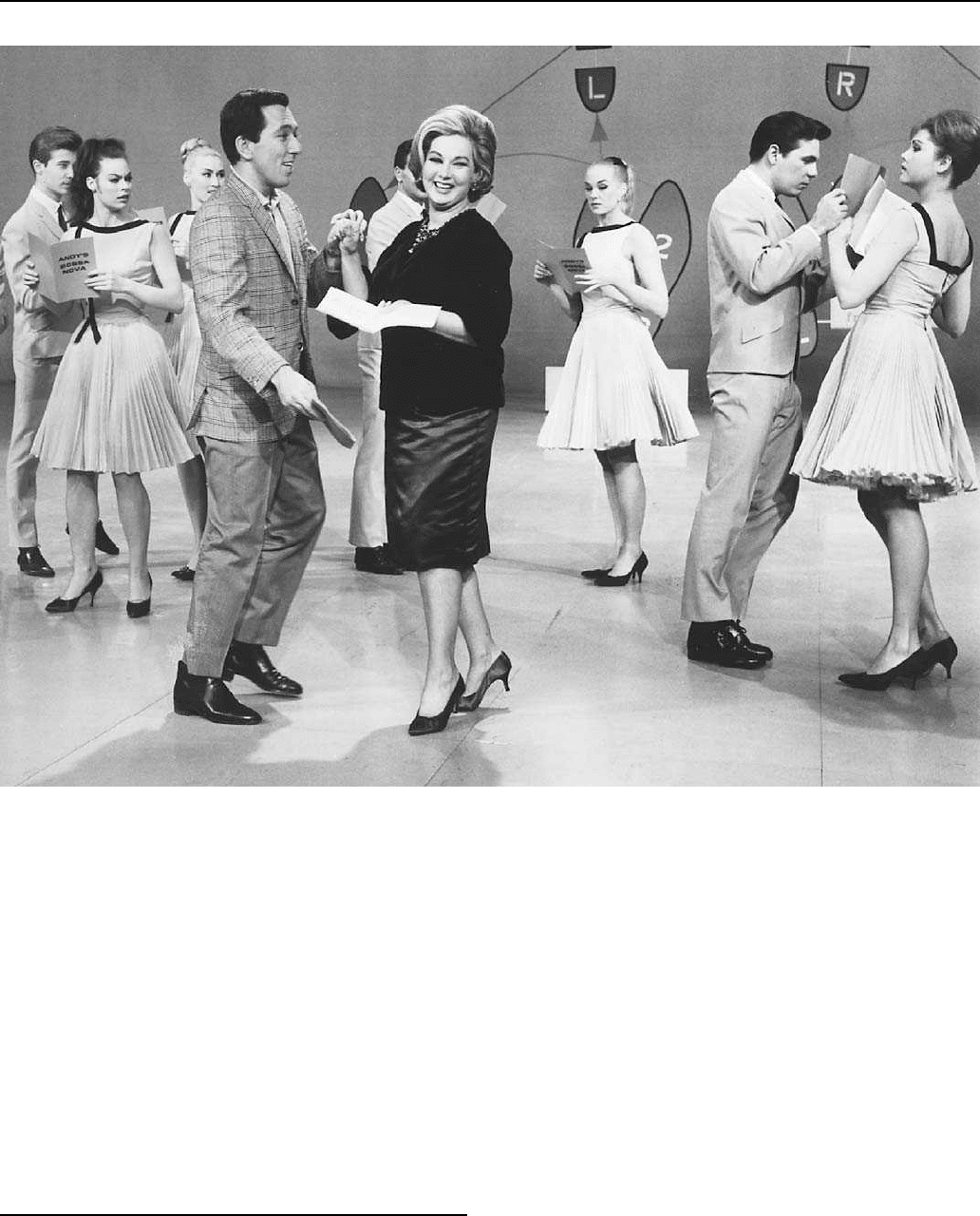

Andy Williams and Ann Sothern (foreground) dancing during a rehersal for the Andy Williams Show.

more popular attractions, providing live music shows for many of the

millions of tourists who visit Branson each year.

—David Lonergan

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network TV Shows. 5th Edition. New York, Ballantine, 1992.

Contemporary Musicians. Volume 2. Detroit, Gale Research, 1990.

Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. 6th Edition. New

York, Billboard Books, 1996.

Williams, Bert (1874-1922)

Known during his lifetime as ‘‘the funniest man in America,’’

Egbert Austin ‘‘Bert’’ Williams enjoyed fame as the straight man and

ballad singer of the African American comedy team of Williams and

Walker. Williams met his partner, George Walker, in San Francisco

in 1893, when he began performing in order to finance his studies at

Stanford University. They worked their way to New York, where in

1896 they appeared in Victor Herbert’s Gold Bug. The two performed

in such musical comedy hits as The Sons of Ham (1900), In Dahomey

(1902), Abyssinia (1905), and Bandanna Land (1907). When Walker

retired, Williams starred in Mr. Lode of Koal (1909) then performed

with Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies from 1910 to 1919. In 1920 Williams

joined Eddie Cantor in Broadway Brevities. Williams was admired

for impeccable comedic timing and pantomimes. He died in 1922

after opening in Under the Bamboo Tree.

—Susan Curtis

F

URTHER READING:

Charters, Ann. Nobody: The Story of Bert Williams. New York,

Macmillan, 1970.

Riis, Thomas L. Just Before Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New

York, 1890-1915. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1989.