Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DEBSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

679

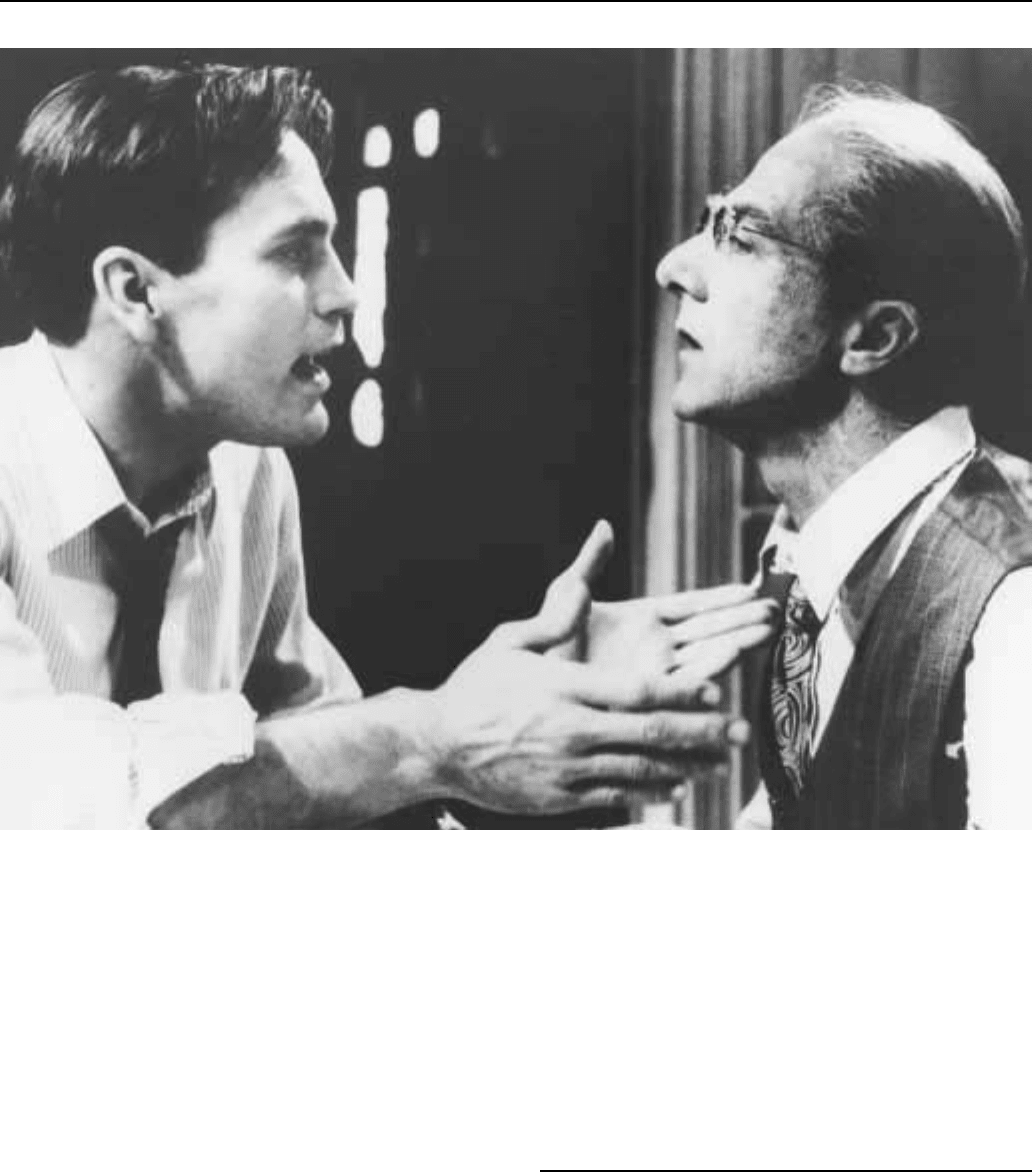

John Malkovich (left) and Dustin Hoffman in a scene from the television production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

Broadway theatre. In the 1950s and 1960s, Miller’s refusal to submit

to the House Committee on Un-American Activities and the on-

slaught of the avant-garde in the theatre both served to squelch his

dramatic voice.

Several productions of Death of a Salesman have been per-

formed to great acclaim, including the 1975 George C. Scott produc-

tion and the 1984 Michael Rudman production starring Dustin

Hoffman, John Malkovich, and Kate Reid, which was later filmed for

television. Other notable productions include the 1983 production at

the Beijing People’s Art Theatre and the 1997 Diana LeBlanc

production at Canada’s Stratford Festival.

—Michael Najjar

F

URTHER READING:

Bloom, Harold, editor. Willy Lowman. New York, Chelsea House

Publishers, 1991.

Klaus, Carl H., Miriam Gilbert, and Bradford S. Field, Jr. Stages of

Drama: Classical to Contemporary Masterpieces of the Theater.

2nd ed. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Martine, James J. Critical Essays on Arthur Miller. Boston, G. K. Hall

& Co, 1979.

Miller, Arthur. Timebends: A Life. New York, Grove Press, 1987.

Roudanè, Matthew C. ‘‘Death of a Salesman and the Poetics of

Arthur Miller.’’ Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller. Edit-

ed by Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press, 1997.

Debs, Eugene V. (1855-1926)

Eugene Victor Debs, labor leader and five-time Socialist candi-

date for President, was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on November 5,

1855. Working on the railroads since he was 14, Debs founded the

American Railway Union in 1893. The following year, the union was

destroyed and Debs served six months in jail after a failed strike

against the Pullman company in Chicago. Subsequently, Debs joined

the Socialist Party of America and was their presidential candidate in

1900, 1904, 1908, and in 1912 when he received about 6 percent of

DEBUTANTES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

680

votes cast. Opposing United States entry into World War I, Debs was

sentenced to 10 years in prison for sedition in 1918. In 1920, from his

prison cell in Atlanta, Georgia, Debs ran for the presidency again

gaining about 3.5 percent of the vote. A year later President Warren G.

Harding commuted his sentence and Debs spent his last years in

relative obscurity until his death on October 20, 1926. Debs is

remembered as the most viable Socialist candidate for the nation’s

highest office and as a champion of workers’ rights.

—John F. Lyons

F

URTHER READING:

Ginger, Ray. The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor

Debs. New Brunswick, Canada, Rutgers University Press, 1949.

Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. Urbana,

University of Illinois, 1982.

Debutantes

The debutante (from the French débuter, to begin) is a young

woman, usually of age 17 or 18, who is formally introduced to

affluent society at a ball or ‘‘coming out’’ party. The original purpose

of the ‘‘debut’’ was to announce that young women of prominent

social standing were available for courtship by eligible young men.

This social ritual was necessitated by the traditional upper-class

The Seattle Rhinestone debutantes of 1956.

practice of sending girls away to boarding school where they were

virtually hidden from view—prohibited from dating, attending par-

ties of mixed company, or socializing with adults. A formal an-

nouncement thus introduced the debutante to her social peers and

potential suitors. The custom had been long established among the

aristocracy and the upper classes in England, where debutantes were,

until the mid-twentieth century, presented at Court. In America, the

debutante ball derived from the formal etiquette of the nineteenth

century, but the ritual has been transformed by each generation’s

evolving notions about the proprieties of class, sexual freedom, and

the role of women.

According to the 1883 etiquette reference, The Manners That

Win, a debutante should have graduated school, sing or play an

instrument gracefully, dance with elegance, and know the rules

governing polite society. Having mastered these essential skills, she

was presumed ready for courtship, leading, of course, to marriage—at

the time the single vocational avenue open to the well-to-do woman.

A second purpose was, however, implicit in debut parties of the

Gilded Age. Since debutante balls were private affairs, held at the

family’s residential estate or at a fashionable hotel until the early

twentieth century, they also pointed to a given family’s wealth,

prestige, and style.

By the 1920s, some latitude had relaxed the rules of the debut. In

her seminal Etiquette: The Blue Book of Social Usage (1922), Emily

Post described several ways that a young woman might be introduced

to society. These included a formal ball, an afternoon tea with

dancing, a small dance, or a small tea without music. In addition, Post

listed a fifth and more modest way for a family to announce that a

daughter had reached the age of majority: mother and daughter might

simply have joint calling cards engraved. For the most part, private

debuts had become a thing of the past, replaced by public cotillions or

assemblies that invited prominent young women to make their debuts

collectively. These long established debutante balls include the

Passavant Cotillion in Chicago; Boston’s Cotillion; the Junior As-

semblies in New York; and the Harvest Ball at the Piedmont Driving

Club in Atlanta.

After World War II, the debutante ball spread to almost every

city in America and enjoyed a heyday during the conservative

Eisenhower years. Yet a decade later, anti-establishment sentiment

led many young women of even the most affluent status to abandon

the event, dismissing it as anachronistic snobbery. In addition, sexual

liberation and the feminist movement challenged the very basis of the

century-old convention, as women began to seek both sexual and

professional fulfillment outside of marriage. In the exuberantly

prosperous 1980s, the debutante ball witnessed a popular resurgence

and, by the century’s end, cotillions were frequently being sponsored

by charitable organizations that extended invitations exclusively to

philanthropically active women.

If there is one rule that has not changed over the years, though, it

is the debutante’s dress. She is to wear a white gown, though a pastel

shade may be considered acceptable. Loud colors or black have

remained always inappropriate.

—Michele S. Shauf

F

URTHER READING:

Post, Peggy. Emily Post’s Etiquette. New York, Harper Collins, 1997.

Roosevelt, Eleanor. Eleanor Roosevelt’s Book of Common Sense

Etiquette. New York, Macmillan., 1962.

DEER HUNTERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

681

Schlesinger, Arthur M. Learning How to Behave. New York, Mac-

millan, 1947.

Tuckerman, Nancy, and Nancy Dunnan. The Amy Vanderbilt Com-

plete Book of Etiquette. New York, Doubleday, 1985.

The Deer Hunter

Before Director Michael Cimino’s 1978 film The Deer Hunter,

the only cinematic treatment of the Vietnam War most Americans had

seen was John Wayne’s The Green Berets a decade earlier. By 1978,

however, American audiences were finally ready to deal with the war

on-screen. The Deer Hunter was popular with audiences and critics

alike, nominated for nine Academy Awards and winning five, includ-

ing Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actor (Christo-

pher Walken). The Deer Hunter broke the ground in the cinematic

treatment of Vietnam, opening the door for films like Apocalypse

Now a year later, Platoon (1986), and Full Metal Jacket (1987). All of

these ‘‘Vietnam’’ films shared the same shattering emotional impact

on audiences, but none was as moving as The Deer Hunter.

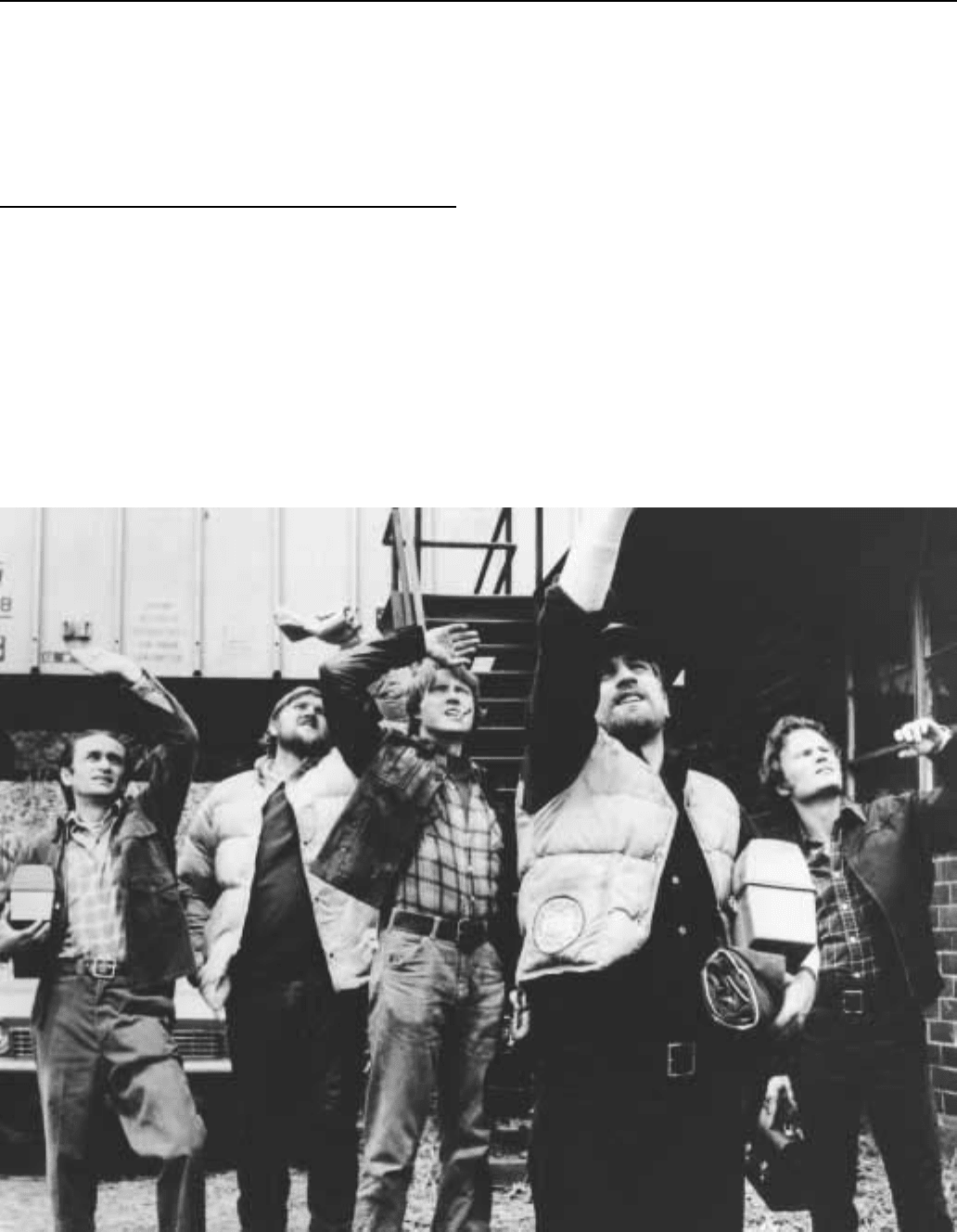

A scene from The Deer Hunter featuring (from left) John Cazale, Chuck Aspegren, Christopher Walken, Robert De Niro, and John Savage.

The Deer Hunter deals not only with Vietnam, but also foregrounds

the contrast between the soldier’s comparatively gentle life at home

with the brutal trauma of war. The film opens in the Clairton,

Pennsylvania steel mill where Michael (Robert DeNiro), Nick (Chris-

topher Walken), and Steve (John Savage) are working their last shift

before shipping out to Vietnam. The quotidian details of their

working-class lives revolve around work, hunting, drinking, and

playing pool. But Steve, like so many soldiers before him, is getting

married before he leaves for the war. Cinematographer Vilmos

Zsigmond beautifully photographs the Russian Orthodox wedding

ceremony, but portents of the war intrude upon the revelry. A Green

Beret mysteriously appears at the wedding like Coleridge’s Ancient

Mariner, foreshadowing the death and destruction that await in Vietnam.

The brutal rituals of war replace the rituals back in Pennsylvania;

however, Cimino and co-writer Deric Washburn use Russian roulette

in a North Vietnamese prison camp as their metaphor for combat. The

Russian roulette game is an ironic, terrifying counterpoint to the trios

hunting and pool playing stateside, and the prison camp scenes are a

chilling condensation of the Vietnam war itself— bamboo, rain, and

death. The end of the film leaves us with three characters that

represent the spectrum of the Vietnam veterans’ experience. Nick

DEGENERES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

682

dies, Steve returns home in a wheelchair, and Michael returns

emotionally crippled.

Besides the emotional impact of the story and the photography,

the film benefits from its excellent ensemble cast. In addition to Oscar

winner Christopher Walken, Oscar nominee Robert DeNiro (Best

Actor), and John Savage, the film stars Meryl Streep (nominee for

Best Supporting Actress), George Dzundza, and John Cazale in his

last film (Cazale died of cancer right after filming was completed).

Stanley Myers’ powerful, melancholy musical score, mostly consist-

ing of a solitary, plaintive guitar, adds to the film’s heartbreaking effect.

The Deer Hunter, according to literary critic Leslie Fiedler, is

‘‘the reenactment of a fable, a legend as old as America itself: a post-

Vietnam version of the myth classically formulated in James Fenimore

Cooper’s The Deerslayer and Last of the Mohicans.’’ The myth that is

played out in The Deer Hunter is an ancient one: The transition from

innocence to experience. War films, according to author John

Newsinger, ‘‘are tales of masculinity. They are stories of boys

becoming men, of comradeship and loyalty, of bravery and endur-

ance, of pain and suffering, and the horror and the excitement of

battle. Violence—the ability both to inflict it and to take it—is

portrayed as an essential part of what being a man involves.’’ No film

before The Deer Hunter and few since have so brutally captures war

as an initiation rite.

—Tim Arnold

F

URTHER READING:

Dittmar, Linda, and Gene Michaud, editors. From Hanoi to Holly-

wood: The Vietnam War in American Film. New Brunswick, New

Jersey, Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Eberwein, Robert T. ‘‘Ceremonies of Survival: The Structure of The

Deer Hunter.’’ The Journal of Popular Film and Television. Vol.

7, 1979, 352-64.

Fiedler, Leslie. ‘‘Mythicizing the Unspeakable.’’ Journal of Ameri-

can Folklore. Vol. 103, 1990, 390-99.

Hellman, John. American Myth and the Legacy of Vietnam. New

York, Columbia University Press, 1986.

Newsinger, John. ‘‘’Do You Walk the Walk?’: Aspects of Masculini-

ty in Some Vietnam War Films.’’ You Tarzan: Masculinity,

Movies and Men. Ed. Pat Kirkham and Janet Thurmim. New York,

St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

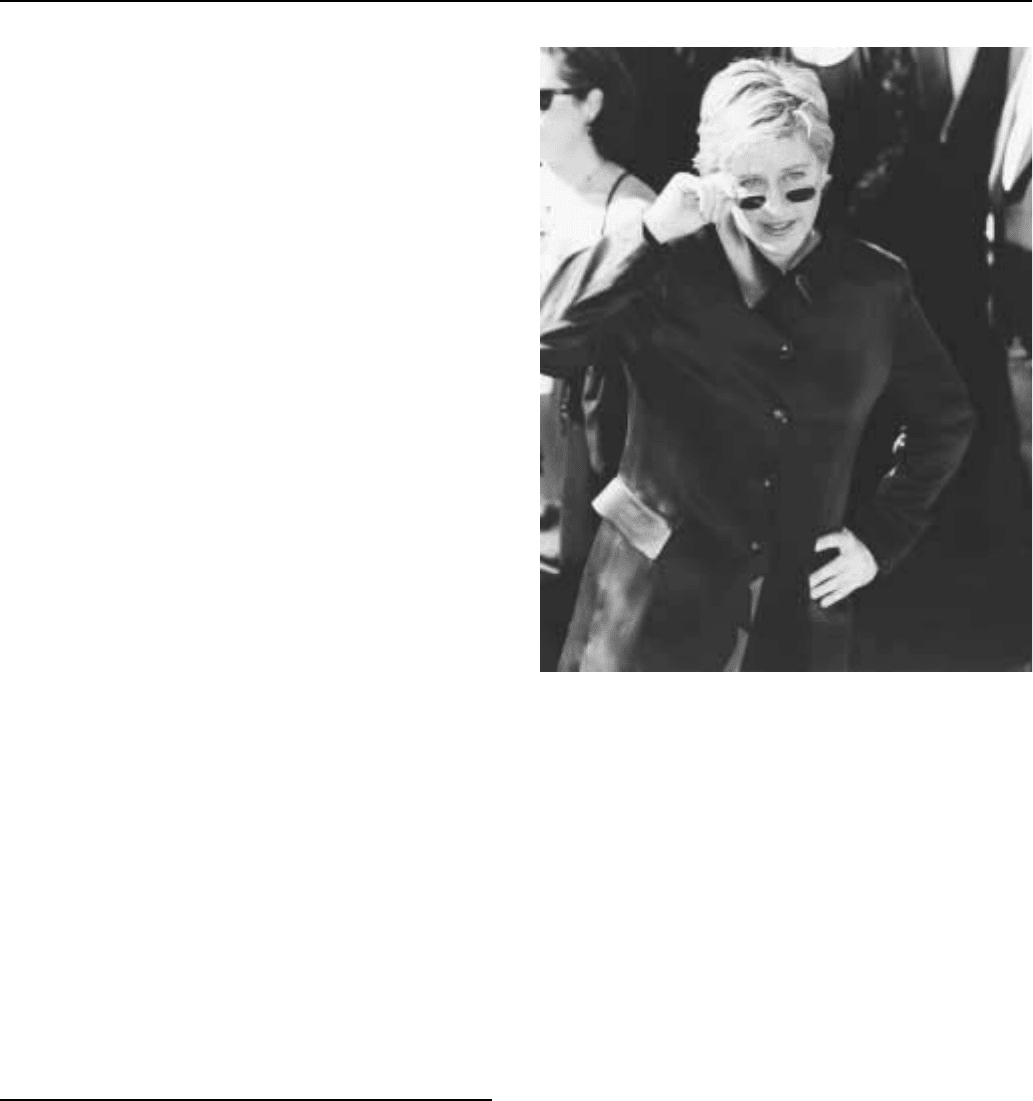

DeGeneres, Ellen (1958—)

Ellen DeGeneres attracted massive media attention when she

came out as a lesbian on her television show in 1997. Known as ‘‘the

puppy episode,’’ the program stirred controversy and drew criticism

from conservative sectors. DeGeneres and her partner, actress Anne

Heche, came out at the same time, DeGeneres appearing on the covers

of national magazines. The caption accompanying her photograph on

the cover of Time read, ‘‘Yep, I’m Gay.’’ Her place in history as TV’s

first gay lead character was thus secured.

Born in New Orleans in 1958, DeGeneres’ sometimes difficult

life inspired her to use humor as a coping device. After her parents’

divorce when she was 13, she and her mother, Betty, moved to Texas.

Ellen DeGeneres

It was a hard time, and DeGeneres used humor to buoy her mother’s

spirits. ‘‘My mother was going through some really hard times and I

could see when she was really getting down, and I would start to make

fun of her dancing,’’ DeGeneres has said. ‘‘Then she’d start to laugh

and I’d make fun of her laughing. And she’d laugh so hard she’d start

to cry, and then I’d make fun of that. So I would totally bring her from

where I’d seen her start going into depression to all the way out of it.’’

After graduating from high school in 1976, DeGeneres moved

back to New Orleans where she worked a series of dead-end jobs:

house painter, secretary, oyster shucker, sales clerk, waitress, bar-

tender, and vacuum salesperson. At the encouragement of friends, she

tried out her comedy on an amateur-hour audience, in 1981. Her act

went over well, and her niche had been found. Only a year later, she

entered and won Showtime’s ‘‘Funniest Person in America’’ contest.

The title, which brought both criticism and high expectations, was her

springboard to stardom.

One of her better-known stand-up routines, ‘‘A Phone Call to

God,’’ came from one of her own darkest moments of despair, when a

close friend and roommate had been killed in a car accident while out

on a date. The girl was only 23, and it seemed very unfair to

DeGeneres. She wanted to question God about a lot of things that

seemed unnecessary, and again she turned to humor. She sat down

one night and considered what it would be like if she could call God

on the phone and ask him about some of the things that troubled her.

As if it was meant to be, the monologue poured from her pen to paper,

and it was funny, focusing on topics such as fleas and what their

purpose might be. DeGeneres performed ‘‘A Phone Call to God’’ on

the Johnny Carson show six years later. Everything clicked that night,

DEMILLEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

683

and Carson signaled her over to sit on the couch after her perform-

ance. She was the only female comedian Carson ever called to come

over and talk to him on a first appearance on the Tonight Show.

DeGeneres continued on the comedy circuit and started acting;

one memorable performance was with dancing fruit in Very Fine

juice commercials. She eventually landed small roles in several short-

lived television series: Duet, Open House, and Laurie Hill. Her

feature acting debut was in the 1993 movie Coneheads.

By 1994 she was starring in a series called These Friends of Mine

on ABC. The first season was aided by a prime slot, following Tim

Allen’s Home Improvement. The network had such confidence in her

that they announced that she would be the ABC spokesperson for

radio ads and on-air promos, allowing her to introduce the debut of

every show in the fall lineup. She also co-hosted the 1994 Emmy

Awards ceremony.

Despite DeGeneres’ fervent backing by ABC, the show had a

number of problems, not the least of which were critical comparisons

to Seinfeld, and a number of personnel changes on both sides of the

camera. The show’s name was changed to Ellen for its second season,

its concept was changed, and Ellen was given more creative input.

By the third season, Ellen had failed to find an audience,

however, and the show needed a boost. DeGeneres and her producers

decided to announce the character’s homosexuality to give the show a

new edge—and to tell the truth. As DeGeneres told Time: ‘‘I never

wanted to be the lesbian actress. I never wanted to be the spokesperson

for the gay community. Ever. I did it for my own truth.’’ After months

of hinting around on the show, Ellen came out in an hour-long episode

featuring guest stars Laura Dern, Melissa Etheridge, k.d. lang, Demi

Moore, Billy Bob Thornton, and Oprah Winfrey. The result was a

clamor among conservatives and the religious right; evangelist Jerry

Falwell called DeGeneres a ‘‘degenerate.’’ The show won an Emmy

for best writing in a comedy series, and a Peabody award for the

episode. Entertainment Weekly named DeGeneres the Entertainer of

the Year in 1997. In 1998, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance against

Defamation (GLAAD) awarded DeGeneres the Stephen F. Kolzak

Award for being an openly gay celebrity who has battled homophobia.

The series itself was given the award for Outstanding TV Comedy.

The show was even praised by vice president Al Gore for forcing

Americans ‘‘to look at sexual orientation in a more open light.’’

In the following season the show continued to focus mainly on

gay issues, despite declining ratings, and ABC decided not to renew

the show for a sixth season. Critics noted that the show had become

one-dimensional, with Ellen’s homosexuality overshadowing all oth-

er topics. As the show declined, however, DeGeneres began branch-

ing out, writing a book, My Point . . . And I Do Have One, in 1996 and

releasing an album collection of stand-up material called Taste This.

She also had her first leading role in a film, a romantic comedy with

actor Bill Pullman called Mr. Wrong. Meanwhile, her series was

picked up in syndication by the Lifetime channel in 1998.

—Emily Pettigrew

F

URTHER READING:

Carter, Bill. ‘‘At Lunch with Ellen DeGeneres.’’ New York Times.

April 13, 1994, C1.

DeGeneres, Ellen. My Point . . . And I Do Have One. New York,

Bantam, 1995.

———. ‘‘Roll Over, Ward Cleaver.’’ Time. April 14, 1997.

Handy, Bruce. ‘‘He Called Me Ellen Degenerate?’’ Time. April

14, 1997.

Hooper, J. ‘‘The Dirty Mind of Ellen DeGeneres.’’ Esquire. May

1994, 29.

Kronke, David. ‘‘True Tales of TV Trauma: 3 Comics Chase Roseanne-

dom.’’ Los Angeles Times. September 4, 1994.

Tracy, Kathleen. Ellen DeGeneres Up Close: The Unauthorized

Biography of the Hot New Star of ABC’s Ellen. New York, Pocket

Books, 1994.

———. Ellen: The Real Story of Ellen DeGeneres. Secaucus, New

Jersey, Carol Publishing Group, 1999.

Del Río, Dolores (1905-1983)

Acclaimed as the female Rudolph Valentino, Dolores del Río

starred in more than 50 full-length motion pictures including Flying

Down to Rio (1933), Journey Into Fear (1942), Las Abandonadas

(1944), Doña Perfecta (1950), and El Niño y la Niebla (1953). With

her first husband, millionaire Jaime Martínez del Río, she traveled

around the world, learned several languages and moved to Holly-

wood. She had an intense love life, marrying three times and having

affairs with Gilbert Roland and Orson Welles, among others. In 1942,

when her career started to decline, she returned to Mexico City. Del

Rio dropped her ‘‘femme fatale’’ image and through Gabriel Figueroa’s

camera and Emilio Fernández’s direction she helped create the so-

called Mexican Cinema Golden Era, winning the Ariel (the Mexican

equivalent of the Academy Award) three times, in 1946, 1952, and

1954. In her later years, her work with orphan children was

highly praised.

—Bianca Freire-Medeiros

F

URTHER READING:

Gonsior, Marian C. ‘‘Dolores Del Rio.’’ In Latinas! Women of

Achievement, edited by Diane Telgen and Jim Kamp. Detroit,

Visible Ink Press, 1996.

Ramon, David. Dolores del Rio. Mexico, Clio, 1997.

Reyes, Aurelio de los. Dolores Del Rio. Ciudad de Mexico, Grupo

Condumex, Fernandez Cueto Editores, 1996.

DeMille, Cecil B. (1881-1959)

Director Cecil B. DeMille epitomized the film epic and Holly-

wood’s ‘‘Golden Age.’’ From the 1910s through the 1950s, he was

able to anticipate public taste and gauge America’s changing moods.

He is best known for his spectacularly ambitious historical and

biblical epics, including The Sign of the Cross, The Crusades, King of

Kings, The Ten Commandments, Cleopatra, Unconquered, and The

Greatest Show on Earth, but he also made domestic comedies such as

The Affairs of Anatol. Originating the over-the-top reputation of

DEMILLE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

684

Cecil B. DeMille

Hollywood filmmakers, DeMille is famous for his huge crowd

scenes, yet his films also clearly demonstrate his mastery as a

storyteller. He avoided camera trickery and developed plots in a

traditional manner that film audiences appreciated. In narrative skill

and action, DeMille had few competitors.

Cecil Blount DeMille was born in Ashfield, Massachusetts, on

August 12, 1881. His father was of Dutch descent and an Episcopalian

lay preacher, Columbia professor, and playwright. His mother, Bea-

trice Samuel, also occasionally wrote plays and ran a girls’ school.

DeMille attended the Pennsylvania Military Academy from 1896 to

1898 and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York from

1898 to 1900. He had his Broadway acting debut in 1900 and

struggled to make his living as an actor for the next decade.

Abandoning his acting career in 1913, DeMille went into part-

nership with vaudeville musician Jesse L. Lasky and glove salesman

Samuel Goldfish (later changed to Goldwyn) to form the motion-

picture production company that would eventually become Para-

mount Studios. It was then that DeMille directed his first film, The

Squaw Man, shot on location in the Los Angeles area, bringing

DeMille to the southern California locale he would help develop into

the enclave of Hollywood. The film’s success and popularity estab-

lished DeMille in the nascent motion-picture industry; he was under-

stood to be the creative force at Paramount, not only directing many

films but also overseeing the scripts and shooting of Paramount’s

entire output.

DeMille capitalized on the same themes throughout his lengthy

career. He often used a failing upper-class marriage, an exoticized Far

East, and obsessive, hypnotic sexual control between men and wom-

en. At the same time, he emphasized Christian virtues alongside

heathenism and debauchery. He repeatedly mixed Victorian morality

with sex and violence. DeMille’s popularity can largely be attributed

to his dexterity with these seemingly contradictory positions and their

appeal to audiences.

Instead of focusing on big-name stars, DeMille tended to devel-

op his own roster of players. With the money he saved, he centered his

energies on higher production values and luxurious settings. The

players he developed include soprano Geraldine Ferrar in Carmen,

Joan the Woman, The Woman God Forgot, The Devil Stone, and

DEMPSEYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

685

Gloria Swanson in Male and Female, Why Change Your Wife?,

Something to Think About, and The Affairs of Anatol.

DeMille produced and directed 70 films and participated in

many more. He co-founded the Screen Directors Guild in 1931, and

from 1936 to 1945, he was a producer for Lux Radio Theater of the

Air, a position that consisted of adapting famous films and plays to be

read by noted actors and actresses. He was awarded the Outstanding

Service Award from the War Agencies of the United States govern-

ment and he also received a Special Oscar for lifetime achievement in

1949. His long list of awards continues with the Irving Thalberg

Award from the Academy of Motion Pictures in 1952, the Milestone

Award by the Screen Producers’ Guild in 1956, and an honorary

doctorate from the University of Southern California.

—Liza Black

F

URTHER READING:

DeMille, Cecil B. The Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille. New

Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1959.

Higashi, Sumiko. Cecil B. DeMille: A Guide to References and

Resources. Boston, G. K. Hall, 1985.

———. Cecil B. DeMille and American Culture: The Silent Era.

Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994.

Higham, Charles. Cecil B. DeMille. New York, Charles Scribner’s

Sons, 1973.

Democratic Convention of 1968

See Chicago Seven, The

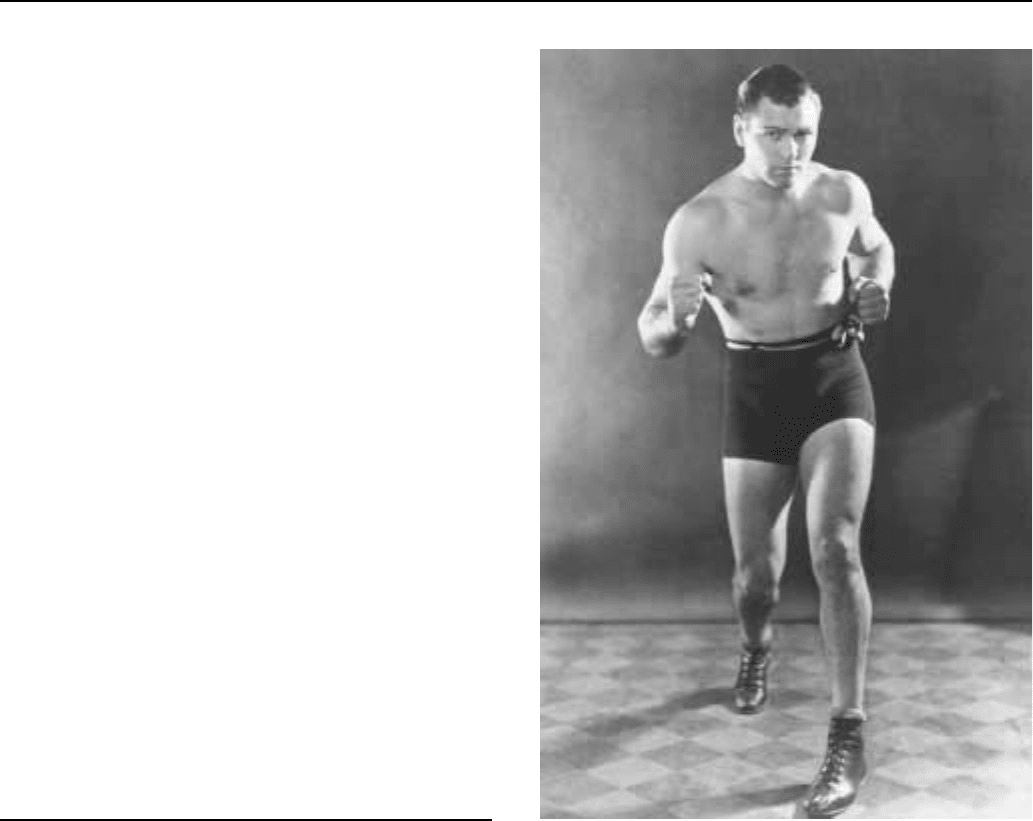

Dempsey, Jack (1895-1983)

Boxer Jack Dempsey heralded the Golden Age of Sports. Like

Babe Ruth, Red Grange, Bill Tilden, and Bobby Jones, Dempsey was

the face of his sport. ‘‘In the ring, he was a tiger without mercy who

shuffled forward in a bobbing crouch, humming a barely audible tune

and punching to the rhythm of the song,’’ wrote Red Smith in the

Washington Post, adding, ‘‘he was 187 pounds of unbridled vio-

lence.’’ Jack Dempsey was a box-office magnet, attracting not only

the first $1 million but also the first $2 million gate. He held the world

heavyweight boxing title from July 4, 1919, when he knocked out

Jesse Willard—who retired at the end of the third round with a broken

jaw, two broken ribs, and four teeth missing—until September 23,

1926, when he lost it to Gene ‘‘The Fighting Marine’’ Tunney on

points after ten rounds. Of a total of 80 recorded bouts he won 60, lost

6, drew 8, and fought 6 ‘‘No Decisions.’’ He knocked out 50

opponents, 25 in the first round; his fastest KO came in just 14 seconds.

Born William Harrison Dempsey in Manassa, Colorado, on June

24, 1895, into a Mormon family of thirteen, young Jack started doing

odd jobs early on but eventually finished eighth grade. At fifteen his

brother Bernie (a prizefighter with a glass chin) started training

William Harry. Dempsey chewed pine gum to strengthen his jaw,

‘‘bathing his face in beef brine to toughen the skin,’’ as he wrote in his

Autobiography. A year later he got his first serious mining job,

earning three dollars a day. When William Harry wasn’t mining, he

was fighting. By 1916 he had already fought dozens of amateur fights.

Jack Dempsey

As ‘‘Kid Blackie’’ he hopped freight trains and rode the rails from

town to town, announcing his arrival in the nearest gym and boasting

that he would take on anyone.

‘‘Kid Blackie’’ became ‘‘Jack’’ Dempsey on November 19,

1915, when he TKOed George Copelin in the seventh round. Dempsey

was actually substituting for his brother Bernie, who had until then

fought under the name of Jack Dempsey, in honor of the great Irish

middleweight Jack Dempsey the Nonpareil, who died in 1895, the

year in which William Harrison was born. The newly named Jack

Dempsey flooded New York sports editors with clippings of his 26

KOs, though no one noticed him but journalist Damon Runyon, who

nicknamed him the ‘‘Manassa Mauler.’’ Late in 1917 Dempsey

caught the attention of canny fight manager Jack ‘‘Doc’’ Kearns, who

recruited him. Under Kearns, the ballyhoo began: Dempsey KOed his

way through the top contenders and within 18 months he took the

heavyweight title from Jesse Willard. Dempsey’s glory was short-

lived, however, for the very next day writer Grantland Rice labelled

Dempsey a ‘‘slacker’’ in his New York Tribune column, referring to

his alleged draft evasion. Though a jury found him not guilty of the

charge in 1920, it took Dempsey six years to overcome the stigma

associated with the label and become a popular champion.

DENISHAWN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

686

Dempsey soon found himself in a peculiarly modern position: he

became a sports hero—or anti-hero—whose image took on extraordi-

nary significance in the climate of publicity and marketing that was

coming to dominate sports promotion. Pre-television marketing tech-

niques which stressed his rogue style of fighting and his alleged draft

evasion turned his title fight against the decorated French combat

pilot George Carpentier into a titanic clash between ‘‘Good’’ and

‘‘Evil.’’ The July 2, 1921, match was a fight of firsts: it was the first

fight ever to be broadcast on radio, the first fight to gross over a

million dollars, and it was fought before the largest crowd ever to

witness a sporting event up to that time. Amid a chorus of cheers and

jeers of ‘‘Slacker!,’’ Dempsey dispatched Carpentier in round three

and somehow won over the 90,000 member crowd. Dempsey defend-

ed his crown several more times, most notably against Argentinian

Luis Angel ‘‘The Bull of the Pampas’’ Firpo. Dempsey sent Firpo to

the floor seven times before Firpo knocked the champ clear out of the

ring to close the first round. Dempsey made it back into the ring and

ended the fight 57 seconds into the second round with a knockout.

Dempsey lost his title on points to Gene Tunney. The resulting

rematch would become one of the most contested fights in boxing

history. Chicago’s Soldier Field was swollen with the 104,943 fans

who packed the stadium for the September 23, 1927, fight and

provided boxing’s first two-million dollar gate. Referee Dave Barry

made the terms of the fight clear: ‘‘In the event of a knockdown, the

man scoring the knockdown will go to the farthest neutral corner. Is

that clear?’’ Both men nodded. Tunney outboxed Dempsey in the first

six rounds, but in the seventh Dempsey unloaded his lethal left hook

and sent Tunney to the floor. Barry shouted, ‘‘Get to a neutral

corner!’’ but Dempsey stood still. At the count of three he moved to

the corner; at five he was in the neutral zone. In one of the most

momentous decisions in boxing history, referee Barry restarted the

count at ‘‘One.’’ Tunney got up on ‘‘Nine’’—which would have been

‘‘Fourteen’’ but for Barry’s restart. Tunney stayed out of Dempsey’s

reach for the rest of the round, floored Dempsey briefly in the eighth,

and won a 10-round decision. The bout, immortalized as ‘‘The Battle

of the Long Count,’’ has been described in an HBO sports documenta-

ry as ‘‘purely and simply the greatest fistic box-office attraction of all

time.’’ Despite the fact that Dempsey lost, the fight allowed him to

reinvent himself, according to Steven Farhood, editor-in-chief of

Ring magazine: ‘‘He was viewed as a villain, not a hero, but after

losing to Tunney, he was a hero and he remained such until his death.’’

Dempsey retired after this match, although he still boxed exhibi-

tions. A large amount of the $3.5 million that he earned in purses was

lost in the Wall Street Crash, but Dempsey was a shrewd businessman

who had invested well in real estate. In 1936 he opened Jack

Dempsey’s Restaurant in New York City and hosted it for more than

thirty years. During World War II, he served as a physical education

instructor in the Coast Guard, thus wiping his alleged ‘‘slacker’’ slate

clean. Jack Dempsey, ‘‘the first universally accepted American sports

superstar,’’ according to Farhood, died on May 31, 1983, at the age of

87 in New York City.

—Rob van Kranenburg

F

URTHER READING:

Dempsey, Jack, with Barbara Piatelli Dempsey. Dempsey. New York,

Harper & Row, 1977.

Evensen, Bruce J. When Dempsey Fought Tunney: Heroes, Hokum,

and Storytelling in the Jazz Age. Knoxville, University of Tennes-

see Press, 1996.

Roberts, Randy. Jack Dempsey: The Manassa Mauler. Baton Rouge,

Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

Smith, Toby. Kid Blackie: Jack Dempsey’s Colorado Days. Ouray,

Colorado, Wayfinder Press, 1987.

Denishawn

In 1915, dancers Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn founded a

pioneering company and training school in Los Angeles that became

known as Denishawn. The training they provided for their students—

who also served as company members—was highly disciplined and

extremely diverse in its cultural and stylistic range. Denishawn toured

worldwide and was the first dance company to tour extensively in

America, bringing the concept of serious dance and an appreciation of

unknown cultures to American audiences. Denishawn students Mar-

tha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman went on to

become legendary dancer-choreographers. Musical director Louis

Horst led the way in the composition of music for dance, while

Pauline Lawrence became a legendary accompanist, costume design-

er, and dance administrator. These students instructed and inspired

succeeding generations, and in this way, the ‘‘family tree’’ of

Denishawn influenced virtually every American dancer and choreog-

rapher in the twentieth century.

—Brian Granger

F

URTHER READING:

The Drama of Denishawn Dance. Middletown, Connecticut, Wesley-

an University Press, 1979.

Sherman, Jane. Denishawn, The Enduring Influence. Boston, Massa-

chusetts, Twayne Publishers, 1983.

Denver, John (1943-1997)

John Denver, so much a part of 1970s music, always marched to

the beat of his own drummer. At a time when the simplicity of rock ’n’

roll was fading to be replaced with the cynicism of punk rock, Denver

carved out his own niche and became the voice of the recently

disenfranchised folk-singer/idealist who believed in love and hope

and fresh air. With his fly-away blond hair and his signature granny

glasses, Denver had a cross-generational appeal, presenting a

nonthreatening, earnest message of gentle social protest.

John Denver was born Henry John Deutschendorf on December

31, 1943, in Roswell, New Mexico. His entire life was shaped by

trying to measure up to his father, who was a flight instructor for the

Air Force. In his autobiography Take Me Home, Country Roads,

Denver described his life as the eldest son of a family shaped by a

stern father who could never show his love for his children. Denver’s

mother’s family was Scotch-Irish and German Catholic, and it was

they who imbued Denver with a love of music. His maternal grand-

mother gave him his first guitar at the age of seven.

Since Denver’s father was in the military, the family moved

often, making it hard for young John to make friends and fit in with

people his own age. Constantly being the new kid was agony for the

introverted youngster, and he grew up always feeling as if he should

DENVERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

687

John Denver

be somewhere else but never knowing where that ‘‘right’’ place was.

Denver was happier in Tucson, Arizona, than anywhere else; but his

father was transferred to Montgomery, Alabama, in the midst of the

Montgomery boycotts. John Denver saw Alabama as a place of hatred

and mistrust, and he wanted no part of it. It was in Montgomery,

however, that he discovered that music was a way to make friends.

When he sang and played his guitar, others paid attention to him.

Nonetheless, he continued to feel alienated and once refused to speak

for several months when he was severely bruised by a broken romance.

Attending high school in Fort Worth, Texas, was a distressing

experience for the alienated Denver. Once he gave a party to which no

one came. In his third year of high school, he took his father’s car and

ran away to California to visit family friends and pursue a musical

career. However, he returned obediently enough when his father flew

to California to retrieve him, and he finished high school.

While studying architecture at Texas Tech, Denver became

disillusioned and dropped out in his third year to follow his dreams.

He managed to get a job at Ledbetter’s, a night club that was a mecca

for folk singers, as an opening act for the Backporch Majority.

Destiny had placed John Denver in the ideal spot for an aspiring

young singer because he found himself living and working with more

established artists who taught the idealistic young entertainer how to

survive in his new world. It was then that he was encouraged to

change his name. He chose Denver to pay homage to the mountains

that he loved so dearly.

John Denver’s big break came when he met Milt Okum, who

represented the folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary. Okum was looking

for a replacement singer for another group, the Chad Mitchell Trio,

and Denver perfectly fit the requirements. Although the group dis-

banded not long after Denver joined, his experience with them taught

him much about the world of professional musicians. When the group

disbanded because of huge debts, Denver felt a personal obligation to

pay them off.

In 1967, while laying over in a Washington airport, John Denver

wrote ‘‘Oh, Babe, I Hate to Go,’’ or as it became known, ‘‘Leaving on

a Jet Plane’’ out of his sense of loneliness and the desire for someone

to ease that desolation. Both the Mitchell Trio and Spanky and Our

Gang recorded the song, but it was Peter, Paul, and Mary who turned

it into a number one hit in 1969. After being turned down by 16 record

companies, Okum negotiated a recording contract for Denver with

RCA Records.

Denver met his first wife Annie in 1966 while touring, and they

were married in June 1967. In 1970 the couple moved to Aspen,

Colorado. They could not afford to build a house on the land they

bought, so they rented and saved. No matter, John Denver had come

home. He had discovered the place he had been seeking his entire life.

Unable to have children, John and Annie adopted Zachery and Anna

Kate. Unfortunately, nothing could hold the marriage together, and it

ended it bitter divorce. A subsequent marriage also ended unhappily,

leaving him with daughter Jessie Bell.

Denver admitted in his autobiography that he had less trouble

talking to large groups of people than to those whom he loved. This

ability that caused him so much damage in his personal life gave him

the uncanny ability to connect with the audience that set his music

apart. His purpose was always greater than simple entertainment. He

clothed his messages in everyday scenes to which everyone could

relate, whether it be the airport of ‘‘Leaving on a Jet Plane’’ or the

forests of ‘‘Annie’s Song’’ or the mountains of ‘‘Rocky Mountain

High’’ or the homecoming of ‘‘Back Home Again’’ or the country

roads of ‘‘Take Me Home, Country Roads’’ or the feather bed of

‘‘Thank, God, I’m a Country Boy’’ or the bad days of ‘‘Some Days

Are Diamonds (Some Days Are Stone).’’ People related to John

Denver as if he were a friend who shared their personal history. His

message behind the simple pleasures of life was always to protect the

world that provides so much beauty and to enjoy life to the fullest

every day because life is a gift.

John Denver’s success would have been impressive at any time,

but it was particularly impressive in the changing environment that

made up the 1970s music scene. He had 13 top ASCAP hits, 9

platinum albums, one platinum single (‘‘Take Me Home, Country

Roads’’), 13 gold albums, and six gold singles. He also had gold

records in Canada, Australia, and Germany. In 1975 he was named

CMA’s Entertainer of the Year and ‘‘Take Me Home, Country

Roads’’ won the best song of the year. He won a People’s Choice

Award, a Carl Sandburg People’s Poet Award, and was named the

Poet Laureate of Colorado. He made 21 television specials, 8 of which

won awards. He was also a successful actor, starring in Oh, God and

Walking Thunder. Denver had come a long way from the young boy

whose friends had ignored his party.

Once his consciousness was raised in the early 1970s, Denver

became an activist for the causes he loved, including campaigning

against nuclear arms and nuclear energy. In 1976, when he was the

country’s biggest recording star, Denver established the Windstar

Foundation on 1000 acres in Snowmass, Colorado, to fight world

hunger. He was deeply hurt when he was not invited to join in the

noted album, ‘‘We Are the World,’’ dedicated to that same cause.

Denver was also the moving force behind Plant-It 2000, a group that

promoted the planting of as many trees as possible by the year 2000.

DEPARTMENT STORES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

688

Denver made his first trip to Africa when he was appointed to

President Jimmy Carter’s Commission on World Hunger. Always

fascinated by space exploration he unsuccessfully sought to be

included in a space mission. Upon his first visit to Alaska, Denver was

captivated by its beauty and worked hard for its preservation. He

became the first American musician to perform in the Soviet Union

and mainland China and even collaborated with Russian musicians on

a project. He often said that he considered himself a ‘‘global citizen’’

because he believed so strongly in an interconnected world.

After the 1970s, Denver’s career declined in the United States

and he was arrested for drugs and driving while intoxicated. He was

involved in a plane crash from which he walked away. Devastated by

his two unsuccessful marriages, Denver remained close to his child-

ren. He also continued to be a strong presence on the international

music scene. Before his death he had begun to reclaim his domestic

audience. With his ‘‘Wildlife Concert’’ in 1995, it was plain to see

that he had matured. The glasses were gone, as was the innocence. His

hair was shorter and neater. His face was lined and often sad. Yet, his

voice was stronger, more sure and arresting. He was still John Denver,

and he still knew how to connect with the audience. Denver followed

the success of the ‘‘Wildlife Concert’’ with a hit album, Best of John

Denver in 1997. Tragically, his comeback was cut short on October

12, 1997, when his experimental aircraft crashed into Monterey Bay.

—Elizabeth Purdy

F

URTHER READING:

Denver, John. Take Me Home, Country Roads: An Autobiography.

New York, Harmony Books, 1994.

Flippo, Chet. ‘‘Artist, Activist Denver Lost to Crash,’’ Billboard,

October 25, 1997, 1.

‘‘John Denver—Poet for the Planet.’’ Earth Island Journal, Winter

1997-98, 43.

Kemp, Mark. ‘‘Country-pop Star Dies in Plane Crash.’’ Rolling

Stone, November 27, 1997, 24.

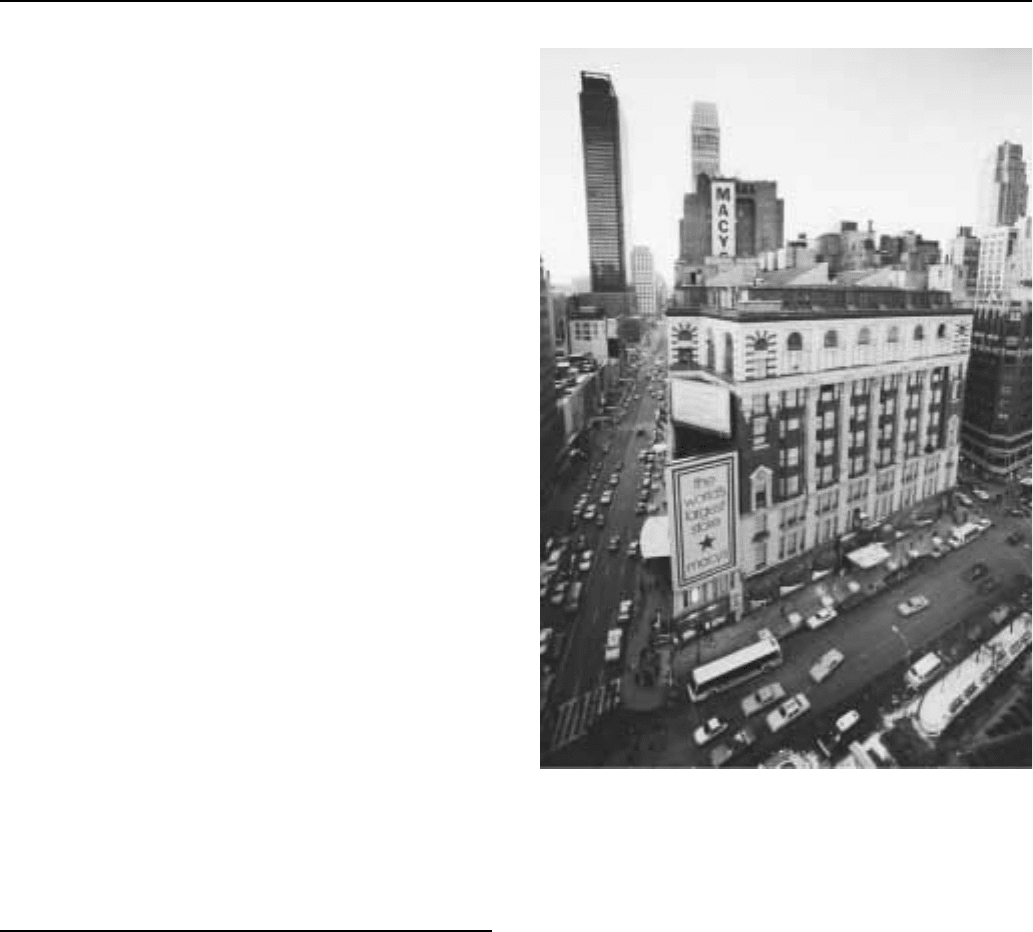

Department Stores

With the creation of the first department stores at the end of the

nineteenth century, came the inception of that most American of

diversions—shopping. Though people had always purchased necessi-

ties, it was the development of the emporium that turned the perusal of

a wide variety of goods, both the necessary and the frivolous, the

affordable and the completely out of reach, into a leisure pastime.

Between the late 1800s and the 1970s, department stores continued to

grow and evolve as the quintessential modern market-place, both elite

and accessible. Huge department stores, named for the families who

founded them, dominated urban centers, and store and city be-

came identified with each other. Filene’s of Boston, Macy’s and

Bloomingdale’s of New York, Marshall Field of Chicago, and Rich’s

of Atlanta are only a few of the stores recognized nationwide as

belonging to their city. The era of the department store is rapidly

fading, replaced by consumer choices that are more consistent with

modern economics, just as the department stores themselves once

replaced their predecessors.

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, citizens began to enjoy

the benefits of a new cash economy. Improved postal service and a

Macy’s, New York City.

new nationwide rail network allowed for an unprecedented flow of

goods. Previously, consumers had been dependent on traveling

peddlers, who carried such stock as sewing needles, thread, and

fabrics from town to town in bulky packs on their backs or in horse-

drawn carts. As these peddlers grew more prosperous, they began to

settle in small storefronts. As economic times improved with the

modernizations of the late 1800s, savvy shopkeepers began to ex-

pand, offering not only a wider variety of goods, but also an air of

refinement and personal service that had previously been available

only to the very rich. An example of this was Marble Dry Goods,

opened by A. T. Stewart in Manhattan in 1846. Stewart set up posh

parlors for his female customers with attentive sales clerks and the

first Parisian style full-length mirrors in the United States. Thus,

department stores drew all classes of customers by making them feel

as if they were part of society’s elite while shopping there.

Owners of the new department stores were able to undercut the

prices of their competitors in the specialty shops by going directly to

the manufacturers to purchase goods, bypassing the wholesalers’

mark-up. Some even manufactured their own products. Where once

stores had been slow, sedate places where goods had to be requested

from behind the counter, the lively new department store displayed

products prominently within reach and encouraged browsing. To

keep customers from leaving, stores expanded to sell anything they