Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PAGE 236.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:50 PS

11

CHAPTER

Mastery of the Machine

The Industrial Revolution, 1764 to 1914

H

istorians call the rough hundred years after the fall of Napoleon the nine-

teenth century (1815–1914). The period forms a convenient unit framed

by the Wars of the Coalition and World War I. Between those two world-

wide conflicts Western civilization went through numerous changes in its economic

practices, political ideologies, social structures, and scientific ideas. Probably the

most important change was the one brought about by the Industrial Revolution

(1764–1914), or economies dominated by manufacturing via machines in factories.

Just as the French Revolution opened up new possibilities, so did the Industrial

Revolution. The rise of new technologies and business practices fashioned the most

profound economic change in human history since the invention of agriculture.

The increasing sophistication of machines both supplied more power to the mas-

ters of those devices and dominated the lives of those who worked with them.

Machinery also propelled Western civilization to further heights of prosperity and

power. Under the leadership of new political ideologies, people increasingly aban-

doned the quaint agricultural ways of the past and forged the now-familiar industri-

alized society of our modern world.

PAGE 237.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:00 PS

238

CHAPTER 11

FACTS OF FACTORIES

The basic structures of civilization had been fairly stable since the prehistoric Neo-

lithic agricultural revolution. For thousands of years, the overwhelming majority of

people, the lower classes, had the assigned task of producing enough food for

themselves, plus a little more for their betters who did not farm. Only the few

privileged people of the upper classes and middle classes were not involved in

tilling the land or raising animals. The environment—insects and rodents, drought,

flood, storm, frost—often threatened to destroy the farmers’ crops. Whole families

labored from dawn to dusk most of the days of the year just to scrape by.

Farming started to become much easier with the Scientific Agricultural Revo-

lution. This revolution began around 1650 in England. Science transformed farm-

ing life, offering more control over the environment than ever before. Scientists

recommended different crops to plant, such as potatoes and maize (corn), because

they grew more efficiently and were more nutritious. They developed new kinds of

fertilizer (improving on manure) and new methods of land management (improv-

ing crop rotation and irrigation), reducing the amount of fallow land. Fences went

up as landlords enclosed their fields, consolidating them into more efficient units.

Thus, fewer farmers could produce more food than before. With fewer jobs in

agriculture to keep everyone employed, a huge social crisis threatened to over-

whelm England. The last traditional protections for peasants of the medieval manor

disappeared. Landlords threw tenants off the land that their families had worked

for centuries. Long-standing social and economic relationships were severed, with

few policies to replace them. The agricultural working class broke up. Even inde-

pendent family farmers with small plots of land lost out when they could not com-

pete against the improved larger estates.

At the same time, more food and better medical science allowed rapid popula-

tion growth. As in ancient Rome after the Punic Wars, large numbers of people

without land began to move to the cities, hoping for work. Others left England,

emigrating to find more farmland, especially in the British colonies of North

America. Yet exporting farm laborers could not solve Britain’s unemployment rates

and a threatening rebellion. Arriving in the nick of time was the Industrial Revolu-

tion, which turned many of the landless rural peasants into urban factory workers.

This revolution began in England. The United Kingdom possessed a number of

inherent advantages, first being its position at the forefront of the Scientific Agricul-

tural Revolution. Second, Britain’s political system of elected representatives

quickly adapted to the new economic options. Third, Non-Conformists (mostly firm

Calvinists who refused to join the Church of England) put their efforts into com-

merce, finance, and industry. Lingering religious discrimination excluded them

from civil service jobs and universities. So instead, the Calvinists’ diligent ‘‘Protes-

tant work ethic’’ (as later coined by sociologist Max Weber) grew the economy.

A fourth advantage for England was its diverse imperial possessions. In the

immediate vicinity, England bound Scotland, Wales, and Ireland into the United

Kingdom of Great Britain. Across the oceans, Britain held Canada, islands in the

Caribbean, Egypt, South Africa, and India. Great Britain ruled the world’s largest

PAGE 238.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:01 PS

MASTERY OF THE MACHINE

239

empire in the eighteenth century, despite the loss in 1783 of the colonies that

became the United States. The British navy, so successful in the Wars of the Coali-

tions against Napoleon, ensured the safety of British merchant ships and their car-

gos around the globe. Far-flung territories provided many products, from cotton to

tobacco. Drinks of imported coffee, tea, and cocoa fueled the schemes of business-

men in cafe

´

s.

Financial innovations gave the English yet more advantages over competitors.

One innovation was the invention of insurance, such as that offered by Lloyd’s of

London, then and today. Insurance companies would calculate risk to business

enterprises, charge according to the odds that those risks would come to pass, and

generally make substantial profits. By covering losses caused by natural disasters,

theft, and piracy, insurance made investing less risky and more profitable. After

1694, the Bank of England also provided a secure and ready source of capital, which

was backed by the government itself. The large number of trading opportunities

within the empire minimized capitalist risk. Altogether, Britain possessed the first

opportunity to seize upon the new industrial innovations.

Finally, three new developments in energy, transportation, and machinery com-

bined to produce the Industrial Revolution. First, improved energy came from har-

nessing the power of falling water with water mills. The second development,

transportation, overcame the constant problem of bad roads. The technology for

paved roads had been neglected since ancient Roman times. Since the fall of Rome,

most roads in Europe were dirt paths that became impassable mud trenches when-

ever it rained. Travel became significantly easier, however, with the building of

canals, or water roads. During the eighteenth century, many canals were excavated

to connect towns within the country. These canals were highly suitable in soggy

England because they actually became more passable with rainy weather. Since

barges were buoyant in water, one mule on a towpath could pull many more times

the tonnage of goods than a horse with a wagon on a muddy path could. While

most canals have long since been filled in or forgotten, for a few decades they were

the very latest in technologically efficient transport.

The third improvement, machines, vastly increased the power of human beings.

The first mechanical devices were invented to make textiles, a huge market consid-

ering that all Europeans needed clothing for warmth, comfort, decency, and dignity.

At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the best technology for making thread

was the single spindle on a spinning wheel, as known from fairy tales. Weaving

cloth was done by hand on a loom, pushing thread through weft and warp.

A series of inventions through the eighteenth century multiplied the efficiency

of one woman at the spinning wheel and loom. The breakthrough of James Har-

greaves’ spinning jenny (1764) used several shuttles to make thread from raw

fibers. The name ‘‘Jenny’’ probably came from a version of ‘‘engine,’’ not a daugh-

ter’s name. Hargreaves certainly ‘‘borrowed’’ important concepts from other inven-

tors and businessmen, who, in turn, took his jenny and made money off of it.

Richard Arkwright, a former wig maker, combined his own and others’ inventions

into the best powered spinning and weaving machines.

Inventors protected their inventions with patents, government-backed certifi-

cates protecting an inventor’s rights. Affording the application process, however,

PAGE 239.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:01 PS

240

CHAPTER 11

and then defending patent rights in court often proved too costly. The overriding

economic benefits to society might also deny an inventor rights to his profits. Vari-

ous inventors sued Arkwright for patent infringement and won. Nevertheless, Har-

greaves died a pauper, Arkwright a wealthy knight. The bold, lucky, and

unscrupulous often succeeded in making fortunes, while rightful inventors died in

poverty and obscurity.

Women’s opportunities in the Industrial Revolution were limited. Men did most

of the inventing of and investing in machines. Women lacked the opportunities to

enter apprenticeships, gain education and training, or attain jobs that would lead

them to develop skills in advanced technology. Likewise, political, economic, and

social structures excluded women from positions of authority and influence. Such

had been the status of most women since the beginning of civilization. As machines

became more important, men even argued that women lacked the ability to be

mechanically minded; men alone were suited for tinkering with technology. But

machines affected every woman’s life, as women worked with them both inside and

outside the home. In the nineteenth century, though, men remained masters of

both women and the machines.

By combining all three innovations in energy, men like Arkwright therefore

launched the Industrial Revolution, transportation, and machinery into the factory

or (in British) the mill system. The alternative had been the cottage industry or

putting-out method, functioning since the twelfth century. The merchants brought

the raw materials to homes, where families used simple machines (such as the hand

loom or spinning wheel) to manufacture (literally from the Latin ‘‘to make by

hand’’) them into finished products. By the end of the late eighteenth century,

however, merchants brought raw materials to a factory, which hired workers to run

the expensive machines. This coordination increased efficiency and lowered prices.

And as prices went down, demand went up, since more people could afford the

machine-manufactured goods, which ranged from linen tablecloths to teacups.

Moreover, as new industrial forms of artificial lighting such as the arc lamp were

invented, shifts of workers could labor around the clock to get the maximum use

out of the machines. Thus, capitalist industrial manufacturing emerged as investors

funded the building of factories for profit.

A second wave of industrialization hit with the invention of steam power. The

breakthrough came in 1769 when James Watt and Matthew Boulton assembled an

efficient steam engine. They had adapted it from machine pumps to remove water

from coal and iron mines (see figure 11.1). Coal had emerged as superior to previ-

ous materials that people burned for energy, namely plant and animal oils, wood,

or peat. With innovation, the coal-fired steam engines vastly increased their energy

output while their physical size shrank. By the 1830s, small steam engines on wag-

ons with metal wheels running on tracks called railroads were transporting both

goods and people (see figure 11.2). Trains on such railways soon eclipsed canals as

the most efficient transportation, since they were cheaper to build and could run

in places without plentiful water. Water travel remained important, though. Steam

engines in ships meant faster, more certain transit across seas and oceans, further

tying together markets of raw materials and manufacturing.

Some people resisted the rise of these machines, most famously the Luddites.

PAGE 240.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:03 PS

MASTERY OF THE MACHINE

241

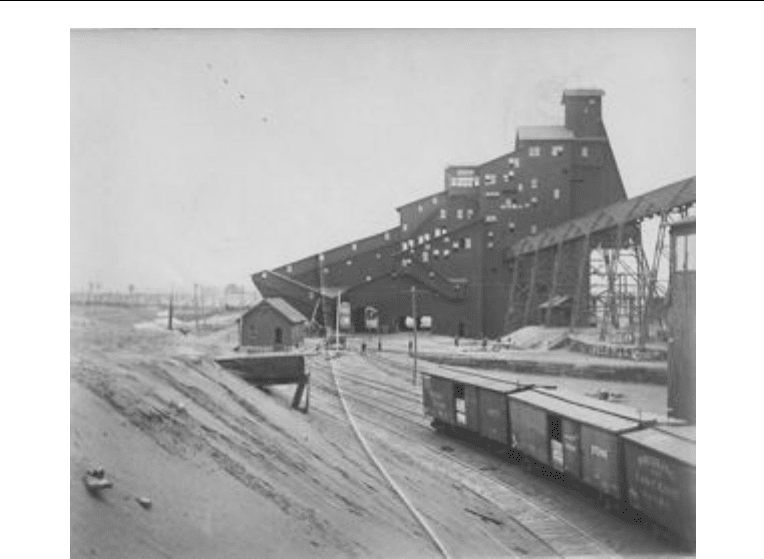

Figure 11.1. A massive coal breaker looms over an industrial wasteland.

Inside, the coal from deep underground was broken down into smaller sizes

for transport.

Today, that label applies to anyone who is suspicious of, or hostile to, technology.

The term originated from the name of a (possibly) mythical leader of out-of-work

artisans. The artisans’ jobs of making things by hand were now obsolete. In the

cold English winter of 1811–1812, bands of artisans broke into mills, destroyed the

machines, and threatened the owners. The government, of course, shot, arrested,

or hanged the troublemakers. Great Britain had a war to win against France and

was not going to let a few unemployed louts threaten what promised to be enor-

mous profit for the nation.

Nevertheless, the Luddite fear was natural and a foreseeable reaction to a

change that left workers vulnerable. At the beginning of the nineteenth century,

classical liberal economics (as described by Adam Smith) had increasingly been

adopted by both business and government. Industrialization meant that only the

entrepreneurial class who controlled large amounts of capital could create most

jobs. Neither factory owners nor politicians felt much responsibility for those

thrown out of work. Some economists, such as the English banker David Ricardo,

told the poor that they should just work harder and be more thrifty. Ricardo’s

‘‘iron law of wages’’ exploited even those who had jobs. With this economic the-

ory, he advised that factory owners pay workers the bare minimum that permitted

survival. Otherwise, he argued, workers might have too many children, only increas-

ing the numbers of the poor and unemployed. The dominant economic theories at

the beginning of the Industrial Revolution favored the new industrial capitalists

over the new factory workers.

PAGE 241.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:34 PS

242

CHAPTER 11

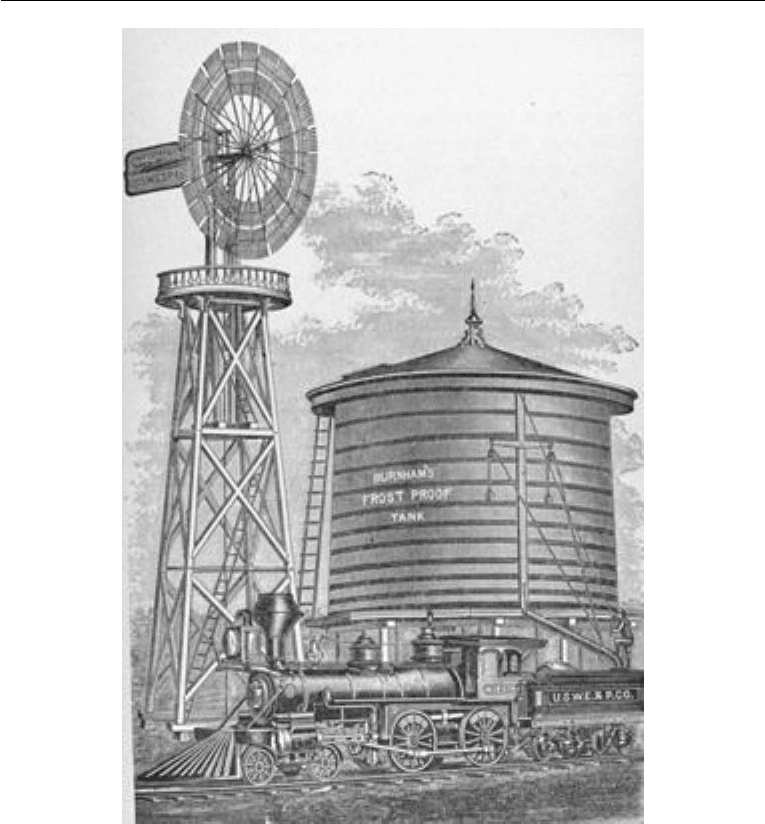

Figure 11.2. Steam engines on railways (with windmills to pump water

from far underground to store in a tank) enabled expansion across the

American continent by the mid-nineteenth century.

Review: How did inventions and capitalism produce the Industrial Revolution?

Response:

PAGE 242.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:48 PS

MASTERY OF THE MACHINE

243

LIFE IN THE BIG CITY

The division of society into capitalists and workers led Western civilization to

become more dependent on cities than ever before. The populations of industrial-

ized cities rapidly rose upward in a process called urbanization. By definition,

cities had been central to civilization since its beginnings, but only a small minority

of people had ever lived in them. Most people needed to be close to the land,

where they could raise the food on which the few urban dwellers depended. After

1800, the invention of machines helped consolidate more people into urban life.

Fewer jobs on the land meant that more people looked for work in the factories.

Cities leapt up from villages and expanded into metropolitan complexes. The old

culture of the small village where everyone knew everyone increasingly waned.

At first, the cities grew haphazardly, in fits and starts, with little planning or

social cohesion. In many sections, people did not know their neighbors, while resi-

dents were paid little or had no employment at all. The result was slums of badly

built and managed housing. Slums became dangerous places of increased drug use,

crime, filth, and disease.

People founded public health and safety organizations to manage these prob-

lems. Firefighters became more professional. Likewise, modern police forces

formed as a new kind of guardian to manage the lower classes. Law enforcement

on the scale at which our modern urban police forces function had been unneces-

sary in earlier rural society. In small, stable rural villages, people had known all

their neighbors, and therefore crime was limited by familiarity. In the anonymous

urban neighborhood, though, crime by strangers inevitably increased. Of necessity,

crime investigations required more care and scientific support. During the 1820s,

Sir Robert Peel’s ‘‘bobbies’’ (nicknamed after their founder) and their headquarters

in Scotland Yard (named after the location) in London were merely the first of these

new civil servants. Police forces insisted that only they could use violence within

the urban community.

The concentrated numbers of new urban dwellers, which rose from hundreds

of thousands into millions, also spewed out levels of pollution unknown to earlier

civilization. Streets became putrid swamps, piled high with dumped rotting food

and excrement. Major cities had tens of thousands of horses as the main mode of

transportation, each producing at least twenty pounds of manure a day. Air became

smog, saturated with the noxious fumes of factory furnaces, coal stoves, and burn-

ing trash. Infectious diseases such as dysentery, typhoid, and cholera (newly

imported from India) plagued Western cities because of unsanitary conditions.

Urban populations died by the thousands with new plagues fostered by industrial-

ization.

Since disease was not confined by class boundaries to only the poorer districts,

politicians found themselves pressured to look after the public health. Cemeteries

were relocated from their traditional settings near churches to parklike settings on

the city’s fringes (in Paris, for example, the bones emptied from cemeteries were

stacked up in huge underground caverns). Regulations prohibited raising certain

PAGE 243.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:48 PS

244

CHAPTER 11

animals or burning specific materials. The government paved roads, especially with

the cheap innovative material of tar and gravel called asphalt or macadam (after its

inventor, McAdam). City officials created sanitation organizations. People called

garbagemen, refuse collectors, or sanitation engineers took trash to dumps. Fresh-

water supply networks replaced the old-fashioned wells, bringing in clean, drink-

able water from reservoirs, while networks of sewers whisked dirty water away as

workers hosed down the streets.

In this process, Western civilization perfected the greatest invention in human

history: indoor plumbing, namely hot and cold running water and a toilet (or

water closet). Such mundane items are often taken for granted by both historians

and ordinary people. The Romans had public lavatories and baths, some medieval

monasteries had interesting systems of water supply, and a few monarchs and aris-

tocrats had unique plumbing built into a palace here or there. But since the fall of

Rome, cleanliness had been too expensive for most people to bother with. Whether

rich or poor, most people literally stank and crawled with vermin. In the nineteenth

century, free-flowing water from public waterworks, copper pipes, gas heaters,

valves, and porcelain bowls brought the values of hygienic cleanliness to people at

all levels of wealth. Of course, not all worries can go down the drain or vanish with

a flush; the waste merely accumulated somewhere else in the environment. Most

people, unconcerned, have easily ignored such messy realities. Regardless, more

and more nineteenth-century westerners enjoyed the cleanliness and comforts of

lavatories. With the new plumbing, plagues like cholera, typhoid, and dysentery

began to diminish and even disappear in the West.

As industrialized cities grew in size and safety, their inhabitants accumulated

wealth previously unimagined in human history. Some of those riches were spent

on culture: literature, art, and music. Some were spent on showing off: bigger

houses, fancier fashion, and new foods. Because a few earned so much more than

the rest, the Industrial Revolution initiated a major transition of class structures in

Western society. At the bottom, supporting the upper and middle classes, was the

hard labor of the working class (also called the proletariat after the ancient Roman

underclass), made up of fewer and fewer farmers and more and more factory work-

ers. The upper classes became less defined by birth once owning land ceased to be

the most productive way to gain wealth. A successful businessman could create a

fortune that dwarfed the lands and rents of a titled aristocrat. The nouveau riche

(newly wealthy) set the tone for the upper crust.

Meanwhile, the middle class became less that of the merchants and artisans and

more that of managers and professionals: the white-collar worker who supervised

the blue-collar workers in the factories. The colors reflect class distinctions: white

for more expensive, bleached and pressed fabric, blue for cheaper and darker cloth

that showed less dirt. Physicians, lawyers, and professors likewise earned enough

to qualify for the ‘‘upper’’-middle-class way of life. Most people came to idealize

middle-class values: a separate home as a refuge from the rough everyday world; a

wife who did not have to work outside the home, if at all; the freedom to afford

vacations; and comfortable retirement in old age.

Essentially, these middle-class values were new, unusual, and limited only to a

PAGE 244.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:49 PS

MASTERY OF THE MACHINE

245

very few. These so-called family values were not at all traditional, as some social

conservatives today would like people to think. Throughout civilized history, most

men and women have actually worked at home or close to home on the land. And

the entire family worked together: husband, wife, and children, perhaps with a few

others in servile status. Most people never thought of vacation trips, only restful

religious holidays. Those who survived into old age usually had to keep working to

earn their keep. For a model of true traditional family life, look to the Old Order

Amish or Pennsylvania Dutch, who live today in communities stretching from Penn-

sylvania to Illinois. These people have consciously rejected the Industrial Revolu-

tion and its technologies. They cannot ignore it, as their young people are tempted

toward the ease that the wealth of modern life provides. Nonetheless, their values

of hard-working farm families were the family values passed down through the

millennia of Western civilization before the Industrial Revolution.

By moving people away from farm communities, the Industrial Revolution gen-

erated serious tensions within society that few people wanted to recognize. The

domestic sphere was damaged, as people worked outside the home. Social mobility

became more volatile, as it was easier to rise but also to fall in class status. One

major business failure could send not just the capitalist owner, but also many thou-

sands of workers, into the poorhouse. For workers at the bottom of society there

were few protections (see below). Businesses rotated through boom and bust, good

times and bad times, hirings and firings. Whole societies became subject to market

cycles, which economists have never been able to predict or prevent, despite their

professorial proclamations.

Over time, though, the Industrial Revolution did seem to confirm the Western

notion of progress. Some people suffered, and still suffer, under the system. But by

and large, things for most people usually got better enough to prevent social col-

lapse. The quality of life improved. More people had more possessions. More peo-

ple became free from ignorance and disease. More people had access to more

opportunities than ever before in human history. Before the Industrial Revolution,

most people stayed at the level at which they were born. Capitalist industrial manu-

facturing, it seemed, had unleashed the possibility for anyone to live the good life,

as least as far as creature comforts went. The only questions seemed to be: What

did those at the bottom need to be able to move up, and how long would they

need to wait?

The modern consumer economy, where unknown distant workers manufac-

tured most things that people used and purchased, only stoked impatience. Gone

were the neighborhood shoemaker, blacksmith, or farmer. Instead, distant capital-

ists encouraged consumers to buy stuff, even if they did not need it. To accomplish

this, advertising became a significant tool for economic innovation. It began with

simple signs in stores where products were bought. Soon, advertising was on every

package and on the side of every road and byway. Advertisers began to create needs

to promote consumer purchases and grow the economy. They defined new forms

of proper usage for the various classes, in hygiene, fashion, and leisure. By the end

of the nineteenth century, majestic department stores served as shopping meccas

for the rich and middle classes in urban centers, while the lower classes could buy

PAGE 245.................

17897$

CH11 10-08-10 09:36:49 PS