Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

226

CHAPTER 10

neither able to find competent ministers nor able to support them for long against

palace intrigues.

Remarkably faithful in his marriage vows (for a Bourbon), Louis likewise lacked

an able woman to rule from behind the scenes, such as Louis XV’s mistress Madame

Pompadour. Louis XVI’s spouse, the notorious Queen Marie Antoinette, contrib-

uted to the growing contempt for the monarchy. Although Marie Antoinette was

the daughter of Maria Theresa Habsburg, she inherited none of her mother’s talents

for governance. She instead preferred parties, balls, masquerades, and the life of

luxury that absolute monarchs enjoyed. She never said something so extreme as,

‘‘Let them eat cake [brioche],’’ when she heard that peasants were begging for

bread; the quote came from a fictional character in a novel. Yet people readily

believed that Marie Antoinette could have said it. Her actions and reputation hurt

her royal husband’s position. Louis XVI’s reign again exposed the great virtue and

fatal flaw of absolutism: everything depended on one person.

As Louis confronted his shortage of funds, he naturally thought of the basic

ways governments raised money: conquest, loans, and taxes. The first choice of war

was risky, and it required money up front to equip the troops. Besides, he had no

readily available excuse to attack anyone. As for the second alternative, the French

banks were tapped out, while foreign banks did not want to take on the risk of

French credit. That left only raising taxes. When Louis tried to raise taxes, however,

the nobles who ran the courts, the parlements, declared that he could not do so.

The nobles hoped to use this financial crisis for their own gain, restoring some of

their long-lost influence. They insisted that the king would have to call the Estates-

General, as Philip IV had done four and one-half centuries earlier. Certainly, as an

absolute monarch, Louis could have just raised taxes. Instead of acting firmly and

risking some civil disturbance, the king gave in.

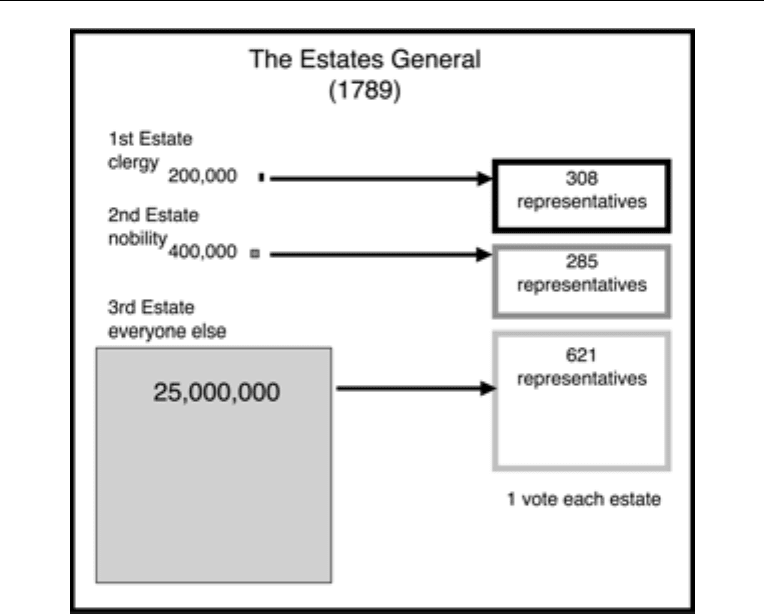

Since no living person remembe red the E stat es-G ener al (it had last met in 1614),

public officials quickly cobbled together a process from dusty legal tomes. Three

hundred representatives should be elected from each of the three estates: the clergy,

the nobilit y, and the common people (althou gh on ly th e top 20 percent of the bour-

geoisie, such as doctors and lawye rs, were a ctua lly eligible to run for election). Some

members of the Third Estate compla ined that their vas tly greater numbe rs compared

with the size of the other two estates deserved more repres ent atio n. The king gave

in, again, and conceded that they could have about six hundred representatives (see

diagram 10.2). While this concession might seem more equitable, it did not c hallenge

the predominance of the first two estates. For one, they were often related to and

connected to one another, so they shared the same views. For anothe r, each estate

voted in a bloc—thus the three hundred clergy had one vote, the three hundred

nobles had one vote, and the six hundred commoners had one vote. Therefore, the

Third E stat e would probably always be o utvo ted 2–1.

Shortly after the representative s to the Estates-Genera l arrived at Versailles for the

opening ceremonies on 5 May 1789, the Third Estat e began to agitate for voting by

individual repr esen tatives, aiming to at least even out the votes to 600–600. They

even tried to declare themselves to be a new legis latu re called the National Assembly.

The kin g was upset by this wrangling and locked the meeting hall on the mo rnin g of

20 June. Many representatives, mostly those from the Third Estate along with a few

PAGE 226.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:37:45 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

227

Diagram 10.2. Even though the First Estate of the clergy and the Second

Estate of the nobility had a tiny proportion of the population (the small

boxes as compared to the huge box of the Third Estate), each had about

an equal number of representatives. Since each estate voted as a unit, the

first two could always easily outvote the third. The quarrel over voting by

estate versus by representative paralyzed the Estates-General.

sympathize rs from the oth er two, proceeded to conven e at a nea rby indoor tennis

court. They swore the Tennis Court Oath, pledgin g not to go home until they had

written a consti tuti on. In fact and in law, a constitu tion meant the end of an absolute

monarchy. Instead of sending in the troops and disbanding this illegal assembly, Louis

once more gave in. Thus the bourgeoisie had seized control and begun a true revolu-

tion.

Things soon got out of control, as so often happens in political revolutions.

While the politicians in Versailles quibbled about the wording of constitutional

clauses, the populace of Paris recognized that change was at hand. They naturally

feared its destructive potential. To protect themselves and their property, some

Parisians began to organize militias, or bands of citizen-soldiers like the minutemen

of America. Yet the Parisians lacked weapons. On 14 July 1789, a semiorganized

mob approached the Bastille, a massive royal fortress and prison in the heart of the

city. The crowd demanded that the Bastille release its prisoners (whom they

believed were unjustly held for political reasons) and hand over its arms to the

Parisian militias.

PAGE 227.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:12 PS

228

CHAPTER 10

The fortress was completely secure from the militia and accompanying rabble,

so the name given to this event, the storming of the Bastille, is quite exaggerated.

In the hope of calming the situation and avoiding too much bloodshed from vio-

lence in the neighborhood, the fortress commander opened the gates. The mob

rewarded him by beating him to death and parading his head on a pike. While the

liberators gained some weapons, they found only a few petty criminal prisoners.

Nevertheless, the attack symbolized the power of the people over the monarch. The

people had openly and clearly defied royal authority and used violence on their

own initiative for their own interests. The citizens of Paris tore down the fortress,

stone by stone, actually selling the rubble as souvenirs. A more forceful and ruthless

monarch would have mobilized his troops, declared martial law, and snuffed out

this attack with notable bloodshed. What did Louis do? Nothing. Again.

Events were soon beyond any possible royal influence. As the peasants in the

countryside heard about the storming of the Bastille, they also decided to rise up.

The ‘‘Great Fear’’ spread as peasants attacked their landlords. The peasants killed

seigneurs and burned the records that documented their social and economic

bondage. The National Assembly panicked, since its members owned much of the

land that the peasants were appropriating. They acted to calm things down on 4

August 1789, abolishing the ancien re

´

gime with its absolute monarchy and feudal

privileges. A few weeks later, the National Assembly issued ‘‘A Declaration of the

Rights of Man and of the Citizen.’’ Similar to the American Bill of Rights, this

document declared ‘‘liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression’’ for all

Frenchmen. It guaranteed liberties to the citizens and restrained government. This

document worked as planned: it calmed passions and allowed the forces of order

to restore moderation. It also originated the phrase ‘‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,’’

which became the slogan for the revolution.

Much more would need to be done for these goals to be realized, but the revo-

lution had issued a clarion call for justice. Sadly, these gains did not apply to

women, as is illustrated by the masculine term fraternite

´

(fraternity/brotherhood).

Revolutionary men in France (just as they had in England and America) excluded

females from the benefits of Enlightenment ideals. A few months later, Olympe de

Gouges proposed ‘‘A Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female

Citizeness,’’ in which she rewrote the original as a document supportive of

women. The government soon executed her. A woman might be a ‘‘citizeness,’’ but

the male citizens enjoyed the real protections and liberties of the law.

The royal family likewise lost their liberty and independence. In October, a mob

(mostly of women) marched from the city of Paris out to Versailles. They ransacked

the palace and escorted the royal family into guarded custody in the palace of the

Tuileries in the heart of the city. The people made Paris once more their capital.

This action shattered any remaining independent royal authority. On the first anni-

versary of the storming of the Bastille, the king swore loyalty to a new constitution.

Louis never reconciled himself to limited authority. In the night of 20–21 June

1791, he and his family fled from their palatial house arrest. A combination of bad

luck, incompetence, and the king’s own hesitant nature allowed revolutionary

forces to catch the royals at Varennes. With the royal family imprisoned and back in

Paris, the French decided they needed a monarch no longer. The legislature tried

PAGE 228.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:13 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

229

King Louis XVI for treason, found him guilty (by 361 to 360 votes), and then had

his head cut off on 21 January 1793. He met his death on the new, lethally efficient

killing machine, the guillotine. Ironically, the king himself had suggested the

machine’s use of a sharp angled blade as a way to improve capital punishment. In

October, Marie Antoinette followed her husband to beheading on the scaffold.

While their daughter survived into old age, their son the Dauphin, or Louis XVII,

disappeared and was presumed dead. Other relatives fled the country. The Bour-

bon dynasty seemed to have ended in humiliation.

The elected bourgeois politicians now running France faced other grave prob-

lems, not easily solved by chopping off heads. The first problem was how to make

political decisions. In a fashion appropriate to democracy, they accidentally estab-

lished a model of political debate and diversity. When the representatives gathered

in the new republic’s National Convention, their seating arrangement gave us the

terminology of modern political discourse. Those to the right of the speaker or

president of the body opposed change. Those to the left of the speaker embraced

change. Those in the middle were the moderates, who needed to be convinced to

go one way or the other. Extremists on the right were reactionaries, and extremists

on the left were radicals (which today tends to be used for any extremist of any

political leaning). This vocabulary of ‘‘left’’ and ‘‘right’’ suggests that all political

disagreements are about resisting or accepting change. These labels may have sim-

plified issues, but they enabled politicians to start organizing groups around ideolo-

gies and specific policy proposals.

Review: How did the revolutionaries in France execute political changes?

Response:

BLOOD AND EMPIRES

The second problem facing the French elected representatives was war. After the

French arrested their king, Louis’ royal relatives and aristocrats called for an inva-

sion to restore their fellow absolutist to power. The French government declared

war before they did. In reaction, an alliance of small and great powers formed

against the French. A series of conflicts, called the Wars of the Coalitions (1792–

1815), burdened Europe for the next generation. Ironically, considering its own

PAGE 229.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:14 PS

230

CHAPTER 10

revolutionary history, Great Britain became the head of the coalition and France’s

most determined opponent. Great Britain sought to maintain the traditional bal-

ance of power among the states of Europe. England feared the growth of French

power more than France’s democratic and republican trappings.

Then suddenly, revolutionary France was the most powerful country in Europe.

The revolution enabled France to create a new kind of war. During the ancien

re

´

gime, many of the French officers in the royal army had been ‘‘blue bloods,’’

aristocrats and nobles so named because one could see their veins through their

fair, pale skin. Many nobles fled the country once revolution began. France’s aristo-

cratic enemies then expected that without God-given elite leadership, the rabble

republican army would readily collapse. On the contrary, the French were inspired

to shed their red blood in defense of their nation more fervently and ferociously

than ever before, since it was theirs now, not the monarch’s. They managed to turn

back the first invading forces in a skirmish at Valmy on 19 August 1792. As the war

ground on, talented officers rose in the ranks based on their ability, not blue-

blooded connections.

The new regime called all the people to war, whatever their status. As ordered

by the government, young men fought, married men supported the troops with

supplies, young and old women sewed tents and uniforms or nursed the sick, chil-

dren turned rags into lint for making bandages, and old men cheered on everyone

else. Modern ‘‘total war’’ began. Key to victory were the huge new armies of

inspired countrymen. The problem of feeding such large numbers of soldiers led

to the invention of ways to preserve food. Scientists discovered that food boiled in

bottles and tin cans for extended periods would not spoil. This invention for war-

time would later free many civilians in peacetime from the danger of starvation.

Under pressure of war and revolutionary fervor, the government became more

radical and willing to take extreme steps in changing society. This phase of the

French Revolution has earned the name the Reign of Terror (June 1793–July

1794), or simply the Terror, an extremist period that lasted only thirteen months.

The radical Jacobins (named after a club where they met) and their leader Robes-

pierre decided that they needed to purge the republic of its internal enemies. They

formed the infamous Committee of Public Safety, which held tribunals to arrest,

try, and condemn reactionaries, in violation of previously guaranteed civil liberties.

As with other historical national emergencies, the government excused itself for its

extreme measures. Actually, the death toll of the Terror was comparatively small (at

least compared with the subsequent war casualties). In Paris, fewer than 1,300 peo-

ple were guillotined. In the countryside, however, death tolls piled higher, with

perhaps as many as 25,000 executed in the troublesome province of the Vende

´

e,

mostly through mass drownings.

During the Terror, radicals implemented Enlightenment ideals with a ven-

geance. The radicals’ new Republic of Virtue threw out everything that the philo-

sophes considered backward, especially if it was based on Christianity. They

replaced the Gregorian calendar: a new year I dated from the declaration of the

republic; weeks were lengthened to ten days; and the names of the months were

changed to reflect their character, like ‘‘Windy’’ or ‘‘Hot.’’ Christian churches

became ‘‘Temples of Reason.’’ Palaces, such as the Louvre, were remodeled into

PAGE 230.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:15 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

231

museums. Education was provided for all children at taxpayer expense. Perhaps

most radical of all, the government required the metric system of measurements.

Tradition and custom were supplanted by the ideas of philosophes.

In the end, the Terror gained ill fame because its leaders became too extreme.

They began to arrest and execute one another, accusing one another of less-than-

sufficient revolutionary passion. Moderates naturally feared that they would be

next. So in the ‘‘Hot’’ month called Thermidor in the republican year II (or in the

night of 27–28 July 1794), moderates carried out a coup d’e

´

tat (an illegal seizure of

power that kills few) called the Thermidor Reaction. The moderates arrested the

radical Jacobin leaders and sent them quickly to the guillotine. The politicians set

up a new, more bourgeois government, restricting vote and power to those of

wealth. The new regime, called the Directorate, was a reasonably competent oligar-

chy, but uninspired and uninspiring.

Meanwhile, the military decisions forced change. The republican French armies

repeatedly gained victory in battle, due to competent commanders, vast numbers,

and inspired morale. Therefore, instead of relying on loans or taxes, the Directorate

used conquest to help pay the bills in 1796–1797. In a series of campaigns invading

parts of Italy and the Rhineland, one general in particular gained the greatest fame:

Napoleon Bonaparte (b. 1769–d. 1821). The dashing General Bonaparte soon

surpassed the bland politicians in popularity, proving again that people are easily

seduced by military successes. While most contemporary monarchs found it safer

to stay away from the battle lines, Napoleon’s leadership provided that inspirational

passion for the French.

Had it not been for the revolution, Napoleon would never have amounted to

anything noteworthy in history. As a Corsican and a member of a low-ranked family,

he could never have risen very high in the ranks of the ancien re

´

gime. The revolu-

tionary transformation of the officer corps and the increased size of the French

army, however, provided Napoleon an opportunity to shine. With military insight

he maneuvered huge armies, negotiated them through foreign lands, and com-

bined his troops to crush enemy forces in decisive blows. Soon the French dreamed

not only of dominating Europe, but also of restoring France’s world empire. In

1798, Napoleon sailed off to invade Egypt, aiming to damage British imperial inter-

ests in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. His only success there was

the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, whose inscriptions in forms of Greek alphabets

and hieroglyphics allowed modern scholars to finally translate ancient Egyptian.

After the British navy decisively crushed Napoleon’s hopes for conquest in

Egypt, he nevertheless managed to rush back to France before news could spread.

Back in Paris he seized control of the government in a coup d’e

´

tat on 18 Brumaire

VIII (or 9 November 1799). Imitating the Roman Republic, Napoleon declared him-

self the First Consul and proclaimed (with about as much sincerity as Augustus

Caesar had) that his leadership would restore the ‘‘French Revolutionary Republic.’’

In a brilliant move, he held a plebiscite for the French people to endorse his sei-

zure of the state. Named after the ancient Roman plebians, plebiscites are votes with

no binding power. So even if the French people had voted against his constitutional

changes, Napoleon could have gone ahead anyway. Napoleon’s real power was

based on his military command. His army could have put down any opposition.

PAGE 231.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:15 PS

232

CHAPTER 10

Nevertheless, the French people felt involved merely by being allowed to vote.

Many a dictator would later resort to the same method of opinion management.

Plebiscites preserved the fac

¸

ade of popular endorsement so well that the trappings

of republican government decorated Napoleon’s absolutism.

Indeed, Napoleon helped establish a model for the modern dictatorship by

weakening the connection between a ruler and a noble dynasty. Napoleon showed

that a relatively obscure, simple person could become the leader of a great power

through talent, luck, and ruthlessness rather than dynastic birth. People were will-

ing to sacrifice their liberty in exchange for victories against neighboring states.

Napoleon’s rise was neither unique nor entirely modern. Many an ancient Roman

emperor had come from obscurity, especially in the tumultuous third century. In

addition, Oliver Cromwell had enforced a benevolent dictatorship over the English.

The lure of dynasty was too powerful for Napoleon to ignore, however. He

crowned himself emperor in 1804, abandoning the titles of the republic. A few

years later he divorced his wife Josephine, who was too old to bear children, so that

he could marry the Habsburg emperor’s young daughter Marie Louise. By marrying

Marie Louise, the once obscure Napoleon joined the most prestigious bloodline in

Europe. Furthermore, the new French empress Marie Louise soon bore her newly

imperial husband an imperial heir.

The French experience reaffirms the basic principle that democracy is difficult.

In trying to establish a republican government, the French instead unleashed dicta-

torship, as had the English under Cromwell. They were not the first to experience

this; nor would they be the last. Sadly, the human tendency to want simple answers

and strong leaders would repeat itself in other revolutions that quickly took the

same sharp turns toward authoritarianism.

For a time, Napoleon’s political activities as ruler of France helped to cement

his positive popular and historical reputation. His foundation of the Bank of France

was only the start to growing a strong economy. Napoleon appeased the spiritual

desires of many French citizens by allowing the Roman Catholic Church to set up

operations again (although without some of its property, power, and monopoly on

belief ). Napoleon himself felt that his greatest achievement was the Napoleonic

Code, a legal codification comparable to Justinian’s Code in the sixth century.

Beyond simply organizing laws as Justinian had, Napoleon’s lawyers tossed out the

whole previous system and founded a new one based on rationalist principles and

the equality of all adult male citizens. These laws were a bit like window dressing,

considering Napoleon’s dictatorship, and, as usual, women were granted very few

rights at all. Nevertheless, Napoleon provided a rationalized system that remained

the foundation of French law as well as that of many other countries today in

Europe (Holland, Italy), Latin America, and even the state of Louisiana in the United

States. On the basis of these reforms, some historians have said that France gained

an enlightened despot in Napoleon, at last.

Napoleon’s military talent forged a massive empire that could have united the

Continent under French power and culture. With his victory at the Battle of Auster-

litz on 2 December 1805, he defeated Austria, Prussia, and Russia. He redrew the

map of Europe and reduced the size of those three great powers. France bloated

into an empire with the annexation of the Lowlands, Switzerland, and much of

PAGE 232.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:16 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

233

northern Italy. With other states forced to be allies, Napoleon’s empire was virtually

the size Charlemagne’s had been. The next year, the Holy Roman Empire vanished

into history, although the Habsburgs kept an imperial title as emperors of Austria.

Bonaparte controlled much of the rest of Europe through puppets, usually his rela-

tives propped up on thrones. He ruled over the largest collection of Europeans up

to that point in history.

Great Britain, however, refused to concede Europe to Napoleonic supremacy .

Britain’s worldwide possessi ons and growing ec onom y gave it the abili ty to maintain

hostilitie s with France until a means could be found t o break up Napoleon ’s empire.

Napoleon himsel f recognized the difficulty of maintaining an overseas empire. He

had given up substantial possessions in the Americas by selling France’s claims to the

Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803 (the indigenous natives who lived

there were not consulted, of cours e). Some weeks before Austerlitz, the British navy

decisively crushed the French fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. At

that point France could not even control the waters off its own coast. This naval

victory notwithstanding, Britain lacked t he forces to invad e France directly.

Thus, one power dominated the land, the other the sea. Neither could or would

end the conflict. Instead, indirectly, the British supported a festering revolt in Spain

after 1808. In turn, Napoleon tried to damage the British economy with his ‘‘Conti-

nental System,’’ which established an embargo prohibiting all trade between his

empire and any allies of the British Empire. Too many Europeans, however, had

become addicted to the products of the global economy (including tobacco and

coffee) that often came through British middlemen. Connections between the West

and the world were increasingly essential to decisions made in the West. Napo-

leon’s higher prices, heavy taxes, and French chauvinism (arrogant nationalism)

alienated many people.

Moreover, the empires of Prussia, Austria, and Russia had merely been defeated,

not destroyed. They waited for an opportunity to strike back. In 1812, Russia’s

refusal to uphold the embargo broke the Continental System. In reaction, Napoleon

decided to teach that country a lesson: he invaded with the largest army yet assem-

bled in human history—probably half a million men. Unfortunately for his grand

plans, the Russians avoided a decisive battle. Napoleon found himself and his huge

army stranded in a burned-out Moscow with winter approaching. As Napoleon

retreated, his forces suffered disaster. Only a few tens of thousands survived to

return from the Russian campaign.

Although Napoleon rapidly raised another army, his dominance was doomed.

Other generals had learned his strategy and tactics too well. Peoples all over Europe

rebelled, aided by British money and troops. The insignificant War of 1812 declared

by the Americans did not distract the British enough to do Napoleon any good at

all. He kept on fighting. The Battle of Nations near Leipzig in October 1813 brought

many peoples together against French domination. More than one hundred thou-

sand men died in one of the largest battles in history. Napoleon remained unbeaten

but had to retreat from Germany. By March 1814, coalition armies had invaded

France and finally forced Napoleon to abdicate.

Incredibly, Napoleon managed to overcome even t his major def eat. For a few

short months, Napoleon sat in impr ison ment on the island o f Elba off the coas t

PAGE 233.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:17 PS

234

CHAPTER 10

of Italy. Th en one nig ht he escaped, and for ‘‘Napo leon’s H und red Days’ ’ he o nce

more ru led a s emp eror of Fr ance . T he coalition refuse d to a cce pt Bo napa rte as

the lea der of a great p ower . British and Prussian forces finally, ultimately, once

and for all d efeated Napol eon at the Battle of Waterloo (18 June 181 5) in Bel-

gium. This t ime the British shippe d the captured empe ror off t o exile on the

barren island of St. Helena in t he South Atla ntic, wher e he died a fe w years later

of a stomach ulcer.

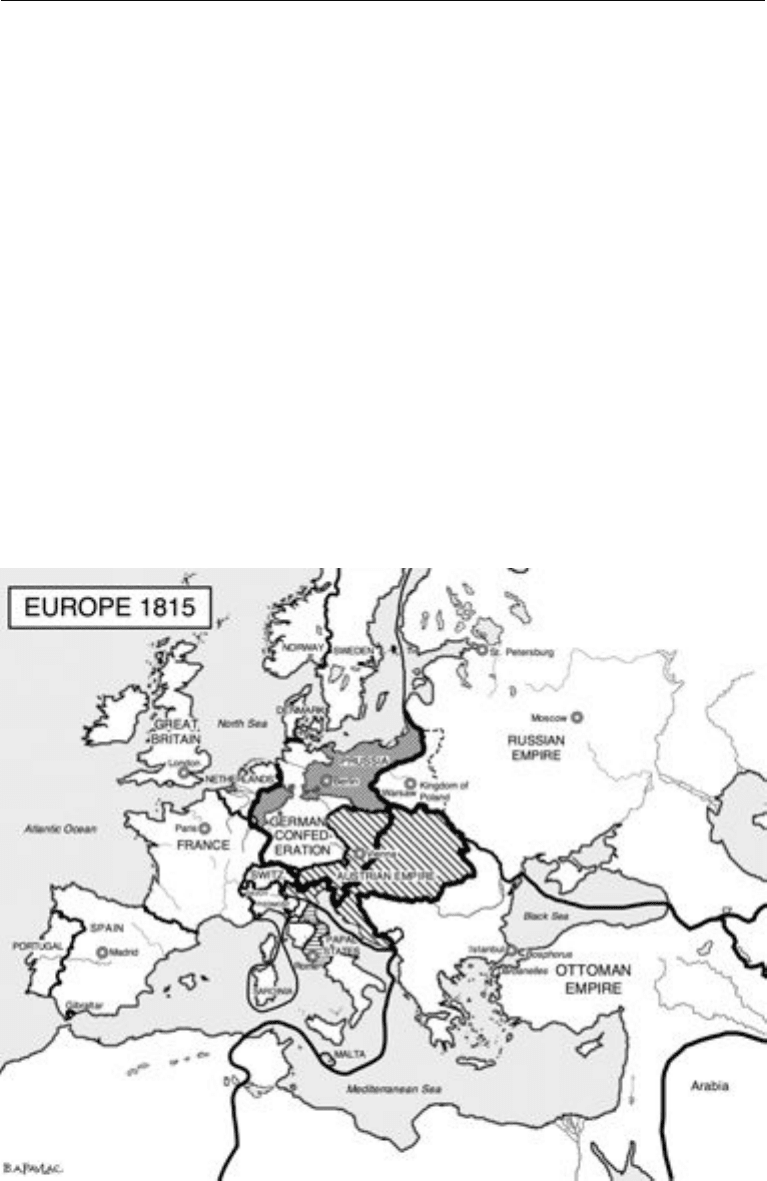

Everyone knew that an era had ended . Millions of lives and vast amounts of

property ha d been lost in r ebel lio n, repres sion, and wars , ca usin g the suff erin g

of whole soc ieti es. The vi ctor s fa ced the questi ons o f wha t sh ould be retain ed and

what sh ould be avoide d (se e map 10.1). T he leaders of the Frenc h Revolution

had proclaimed their inspiration from previous intellectua l and political revolu-

tions. The S cien tific Revol utio n gr ante d Eur opea ns new pow er t o und erst and an d

control nature. The Enlightenmen t freed them to play with new ideas tha t over-

threw a utho rity. New governments, both abs olut ist and d em oc ratic, ga ve Western

states still gre ater abilities to fight w ith one an othe r and conquer fore ign peoples.

Revolution s in Brita in, America, and Franc e provide d exa mpl es of how to change

regimes. Th e legacie s of scientis ts, philosophes, monarchs, republicans , and radi-

cals worked themselv es out on the ruins of Napole on’s empi re. Few suspected at

Map 10.1. Europe, 1815

PAGE 234.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:49 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

235

that ti me how the next century w oul d transform th e West more than an y previous

century had .

Review: How did war alter the French Revolution and cause Napoleon’s rise and fall?

Response:

PAGE 235.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:38:50 PS