Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

196

CHAPTER 9

suggest plans for action on how best to harness capitalism. Unlike scientific theories

(see chapter 10), though, no economic theory has as yet sufficiently explained

human economic activity.

The early economic theory of mercantilism linked the growing Early Modern

nation-states to their new colonial empires. Theorists emphasized that the accumu-

lation of wealth in precious metals within a country’s own borders was the best

measure of economic success. Mercantilist theory favored government intervention

in the economy, since it was in governments’ interest that their economies succeed.

The theory argued that a regime should cultivate a favorable balance of trade as a

sign of economic success. Since most international exchange took place in bullion,

actual gold and silver, monarchs tried to make sure that other countries bought

more from their country than they bought from other monarchs’ countries. Thus,

the bullion in a country’s treasury would continue to increase. Monarchs then

obsessed about discovering mines of gold and silver, a practically cost-free method

of acquiring bullion.

Because of this tangible wealth, governments frequently intervened by trying to

promote enterprises to strengthen the economy. State-sponsored monopolies had

clear advantages for a monarch. A state-licensed enterprise, such as importing tea

leaves from China or sable furs from Siberia, could easily be supervised and taxed.

Diligent inspections and regulation ensured that monopolies’ goods and services

were of a high quality. The government could then push and protect that business

both overseas and domestically.

Fueled by this burgeoning capital and developing theory, more explorers sailed

off to make their fortune by exploiting the riches of Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

Unfortunately for imperialists, the world was fairly crowded already with other

powerful peoples. Various kingdoms and states in East Asia (the Chinese Empire,

Japan), the Indian Subcontinent (the Mughal Empire), and Africa (Abyssinia) had

long histories, rich economies, sophisticated cultures, and intimidating armies. In

comparison, from antiquity through the Middle Ages, Europe had remained a minor

market on the fringe of the Eurasian-African economy.

Even so, Spain and Portugal boldly divided up the world between them, even

before Vasco da Gama had reached the Indies, with the Treaty of Tordesillas

(1494). The pope blessed the proceedings. The treaty demonstrated a certain

hubris in those two states. They claimed global domination, notwithstanding their

inability to severely damage the rich, powerful, well-established, and disease-resis-

tant kingdoms and empires of Africa and Asia. The European powers ruled the

oceans but could only nibble at the fringes of Asia and Africa.

People of other Western nations did not let the Spanish and Portuguese enjoy

their fat empires in peace for long. Outside the law, pirates in the Caribbean along

the Spanish Main (the Central and South American coastline) and in the Indies

plundered whatever they could. Within the law, a few captains preyed on the Span-

ish and Portuguese, each other, and the foreign peoples almost like pirates,

licensed by governments with ‘‘letters of marque.’’ For example, raids by the

English Sir Francis Drake and his sea dogs helped provoke the Spanish Armada.

By 1600, the Dutch, the English, and the French had launched their own over-

seas ventures, with navies and armies grabbing and defending provinces across the

PAGE 196.................

17897$

$CH9 10-12-10 08:34:22 PS

MAKING THE MODERN WORLD

197

oceans. They all began to drive out natives in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. They

also turned on one another. In Asia and Africa, the Dutch grabbed Portuguese bases

in South Africa and the East Indies. The English, in turn, seized Dutch possessions

in Africa, Malaysia, and North America (turning New Holland into New York and

New Jersey). The English planted their own colonists along the Atlantic seacoast of

North America. The French settled farther inland in Quebec. Likewise, in the Carib-

bean, India, and the Pacific, the French and English faced each other in disputes

about islands and principalities, while the native peoples were caught in the

middle.

The slowness and fragility of transportation and communication did mean that

the governments in the homelands could not closely supervise the colonies. West-

erners both in Europe and abroad comforted themselves that their success justified

their dominion, even though it lacked any legal basis except an invented right to

seize allegedly empty or neglected land. The new elites of European heritage immi-

grated to these distant lands and began to forge their own unique cultures, drawing

on Western civilization but also able to adapt to local circumstances. The ‘‘illegal

immigrants’’ only rarely learned from the native peoples, except, if at all, how to

properly farm in new climates and soilscapes, both in the tropics and in temperate

zones.

Everywhere they went, the colonizers ravaged the native cultures, often with

cruelty (scalping was invented by Europeans) and carelessness (smashing sculp-

tures and pulverizing written works). Priceless cultural riches vanished forever.

Land grabbing displaced the local farmers, while slavery (whether in body or wages)

and displacement of native peoples by Europeans dismantled social structures.

Where social bonds did not snap apart, European immigrants ignored and discrimi-

nated, trying to weaken the hold of native religions, languages, and even clothing

styles. Robbed of their homes and livelihoods, most non-European subjects found

resistance to be futile against the weight of European economic and political deci-

sions.

As a result of the westerners’ expansion around the world, ‘‘Europe’’ replaced

‘‘Christendom’’ in their own popular imagination. Nevertheless, these diverse Euro-

peans continued to hurl insults and launch wars against one another, which they

promoted through grotesque ethnic stereotypes. While the people of one’s own

nation were invariably perceived as kind, generous, sober, straight, loyal, honest,

and intelligent, they might allege that the Spanish were cruel, the Scots stingy, the

Dutch drunk, the French perverted, the Italians deceptive, the English boastful, or

the Germans boorish. So Europeans remained pluralistic in their perceptions of

one another.

At the same time, the elites recognized their common bonds in how they prac-

ticed their gentlemanly manners in ruling over the lower classes, expanded their

many governments, grew their increasingly national economies, and revered the

Christian religion (no matter how fractured). Some Europeans adopted a notion of

the morally pure ‘‘noble savage’’ as a critique on their own culture. Missionaries

preached the alleged love and hope of Christianity, while global natives found

themselves confronted by new crimes brought in by the westerners, such as prosti-

tution and vagrancy. The West’s confidence in its civilization made westerners feel

PAGE 197.................

17897$

$CH9 10-12-10 08:34:23 PS

198

CHAPTER 9

that they deserved superiority over all other peoples. These diverse Europeans

insisted that they themselves were ‘‘civilized’’ and that their dominated enemies

were ‘‘savages.’’ They began to think more in racist categories, ‘‘white’’ Europeans

and ‘‘colored’’ others, whether ‘‘red’’ American Indians, ‘‘brown’’ Asian Indians,

‘‘yellow’’ Chinese, or ‘‘black’’ sub-Saharan Africans. All these other ‘‘races’’ by defi-

nition were believed to be less intelligent, industrious, and intrepid. Through

increasing contacts with other peoples, the rest of the world seemed truly ‘‘for-

eign.’’

This Eurocentric attitude is reflected in the early maps of the globe. Medieval

maps had usually given pride of place in the center to Jerusalem. By the sixteenth

century, geographers had a more accurate picture of the globe and could distin-

guish other continents as connected to one another by at most a narrow isthmus

(Panama for the Americas, Sinai between Eurasia and Africa). Nonetheless, they

‘‘split’’ the continent of Eurasia into ‘‘Asia’’ and ‘‘Europe,’’ arbitrarily deciding on

the Ural Mountains as a dividing point (although these hills hardly created a bar-

rier—as the Huns and Mongols had demonstrated). Westerners saw vast stretches

of eastern Europe as hardly civilized at all, a tempting target for building empires.

From living in one small corner of the map, Europeans in all their varieties had

moved to the center. Certainly, the explorers who led the voyages of discovery

showed audacity and heroism, added to the scientific knowledge of Europeans, and

allowed some mutually beneficial cultural exchange. But they were also expansion-

ist and imperialist. Wielding a newfound global power, Western civilization was

unleashed on the world.

Review: How did the ‘‘voyages of discovery’’ begin colonial imperialism by Europeans?

Response:

PAGE 198.................

17897$

$CH9 10-12-10 08:34:23 PS

10

CHAPTER

Liberation of Mind and Body

Early Modern Europe, 1543 to 1815

W

hile people fought over forms of faith, they also pondered man’s place in

God’s creation. Was each person’s position ordained and unchangeable,

or could people achieve something higher than the status into which they

were born? The increasing use of the mind, as advocated by the humanists of the

Renaissance, supported the latter attitude. Yet the more time European intellectuals

spent examining the writings of the Greeks and Romans about the natural world,

the more they discovered flaws and mistakes. If the philosophy of antiquity could

be so wrong, then how did one find truth? Western civilization provided a new

method with the so-called Scientific Revolution (1543–1687), which unleashed

an ongoing force for change and power. Ideas that freed people from ignorance

about nature would in time lead them to question all of society and then to trans-

form politics.

LOST IN THE STARS

A religious problem, ironically, triggered the invention of modern science. The

Julian calendar from 45

B.C.

had become seriously out of sync with nature. As men-

PAGE 199.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:34:28 PS

200

CHAPTER 10

tioned in chapter 5, Julius Caesar had reformed the calendar by adding a leap day

every fourth year to compensate for 365 1/4 days of the solar year. According to the

Julian calendar, the first day of spring (the vernal equinox, when the hours of day

exactly equaled those of night) should occur on 21 March. By the fifteenth century,

the vernal equinox fell in early April. The Church feared that this delay jeopardized

the sanctity of Easter (which was celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full

moon following the vernal equinox). The Counter-Reformation papacy, eager to

have its structures improved and reformed, called on intellectuals to come up with

both an explanation about the calendar’s discrepancy and a solution.

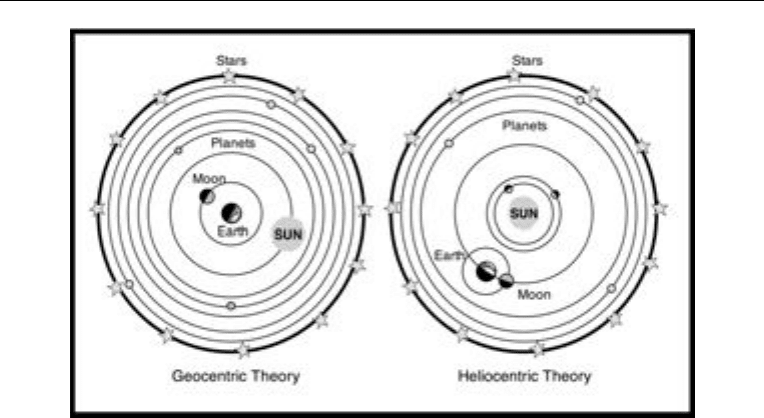

The dominant Aristotelian philosophy hindered a resolution at first. Ever since

the victory of Scholastic ism in the Middle Ages, most intellectuals accepted Aristo tle’ s

logical assertion that the earth sat at the center of the universe. According to Aristotle,

the sun, the moon, the other planets, and the stars (attached to giant crystallin e

spheres) revolved around the earth (which every educated person knew was a globe).

The Greek philosopher Ptolemy had elab orate d on this idea in the second century

A.D.

Aristotle and Ptolemy’s earth-centered universe was labeled the Ptolemaic or geo-

centric theory. After the success of Aquinas and the Scholastics, the western Catholic

Church endorsed this Aristotelia n view. It liked the argumen t that proximity to the

center of the earth (hell’s location) corresponded with impe rfec tion and evil, while

distance from earth ( towa rd heaven) equale d goodness and perfection.

The geocentric theory was not the only reasonable view of the universe, how-

ever. A few other ancient Greeks had disagreed with Aristotle’s concept and argued

instead that the sun was the center of the universe, with the earth revolving around

it (and the moon revolving around the earth). Two planets, Mercury and Venus,

were therefore closer to the sun than the earth, while the other planets and stars

were farther out. This sun-centered universe was called the heliocentric theory

(see diagram 10.1).

Many people today misunderstand the meaning of a scientific theory, probably

because the word theory has multiple definitions. In science, a theory does not

mean something ‘‘theoretical’’ in the sense of a possible guess that is far from cer-

tain. Rather, a valid scientific theory explains how the universe actually works and

is supported by most of the available facts and contradicted by very few, if any. If

not much is known, then several opposing theories may well be acceptable. After

scientists have asked new questions and new facts have been discovered, a scientific

theory may either be invalidated and discounted or supported and strengthened.

Without any winning evidence either way, Renaissance intellectuals could, at first,

reasonably see both the geocentric and the heliocentric as valid scientific theories.

Nevertheless, as scientists discovered new information, the geocentric theory soon

failed to explain the heavens, while the heliocentric theory won support.

As sixteenth-century astronomers looked at the heavens, they discovered the

information that they needed to correct the calendar. They measured and calcu-

lated the movement of the stars and planets. They figured out that the year is actu-

ally a fraction less in length than the 365 1/4 days used by the Julian calendar.

Therefore, a new calendar was proposed, one that did not add a leap day in century

years that were not evenly divisible by four hundred. For example, 1900 would not

have a leap day, but 2000 would. Pope Gregory XIII adopted these changes in 1582,

PAGE 200.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:34:29 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

201

Diagram 10.1. Geocentric vs. Heliocentric Theory. Based on their

observations and perspectives, ancient Greek philosophers had first

proposed these theories for the structure of the universe.

giving Western civilization the Gregorian calendar to replace the Julian. He

dropped ten days from that year to get the calendar back on track with the seasons:

thus the day after 5 October 1582 became 15 October 1582, at least in those areas

that accepted papal authority. Anglican England and Orthodox Russia waited until

centuries later to conform to the papal view, partly because they were suspicious

about anything that came from the Roman Catholic Church.

Yet the papacy had its own problems with science. Earlier, in 1543, the canon

and astronomer Mikolaj Kopernig in Poland (who used the Latinized name Nico-

laus Copernicus) published a book, Concerning the Revolutions of the Celestial

Bodies, which argued convincingly for the heliocentric theory. Copernicus knew

the controversy that this position would provoke and had waited to publish it until

he was on his deathbed. As he expected, the Roman Catholic Church rejected his

argument out of hand and put his study onto the Index of Forbidden Books. The

papacy told astronomers they had to support the geocentric theory because it con-

formed to their preferred belief system of Aristotle and Scholasticism.

The Roman Catholic Church’s beliefs notwithstandin g, new evidence continued

to undermin e the geocentric theory and support the helioc ent ric theory. The best

facts were presented by Galileo Galilei (b. 1564–d. 1642) of Florence. In 1609, he

improved a Dutch spyglass and fashioned the first functional telescope, which he

turned toward the heavens. Galileo discovered moons around Jupiter, mountains

and craters on the moon, sunspo ts, and other phenomena that convinced him that

the heavens were far from Aristotelian perfection. His publication the next year, The

Starry Messenger, supported the Copernican theory. It sparked a sensation among

intellectu als, while it also angered leade rs of the Roman Catholic Church. Clergy

warned Galileo his ideas were dangerous. Therefore, he kept silent until he thought

a pope had been electe d who would suppor t his inquirie s. Cautiously, he framed his

PAGE 201.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:35:18 PS

202

CHAPTER 10

next bo ok, Dialogue on the Chief World Systems (1 636), as a debate i n which the

Copernican view tech nica lly lost but t he Aristotelian view looke d indefensibly stupid.

The papacy saw through the device. The Roman Inquisition called in the aged

man and questioned him, using forged evidence. The Inquisitors threatened Gali-

leo with the instruments of torture, probably including pincers, thumbscrews, leg-

screws, and the rack. They defined disagreement with the Roman Church as heresy,

and thus Galileo was automatically a heretic. Galileo pled guilty, and the Inquisition

sentenced him to house arrest for the rest of his life. The aged scientist nonetheless

continued experiments that helped lay the foundation of modern physics. His stud-

ies increasingly showed that Aristotle was incorrect about many things, not only the

location of the earth in the universe.

A person born in far-off England during the year Galileo died, Isaac Newton

(b. 1642–d. 1727), assured the doom of Aristotle’s views about nature. Newton first

studied the properties of light (founding modern optics) and built an improved

reflector telescope, which he also turned to the heavens. From his studies of the

planets, Newton accepted the Copernican/heliocentric theory, but he still wanted

to find an explanation for how stars and planets stayed in their orbits while apples

dropped from trees to the ground.

Newton started from that inspirational falling apple and continued with the

invention of calculus to help him measure moving bodies. He finally arrived at an

explanation for how the universe works, published in the book Principia (1687).

In that treatise, Newton’s theory of universal gravitation accounted for the move-

ments of the heavenly bodies. He showed that all objects of substance, everything

with the quality of ‘‘mass,’’ possess gravitational attraction toward one another. So

the moon and the earth, just as an apple and the earth, are being drawn toward

each other. The apple drops because it has no other force acting upon it. The

moon stays spinning around the earth because it is moving fast enough; its motion

balances out the earth’s gravitational pull. The delicate opposition of gravity and

velocity keeps the heavens whirling.

With the publication of the Principia, many historians consider the Scientific

Revolution to have triumphed, having created the modern, Western idea of science.

Between the years of Copernicus and Newton’s books, other intellectuals such as

Francis Bacon and Rene

´

Descartes had worked out basic scientific principles. Tradi-

tional authorities, such as Aristotle, were to be doubted until proved. Instead of rely-

ing on divine revelation or reason (the big debate of the Middle Ages), trustworthy

knowledge could be obtained through a speci fic tool of reason called the scientific

method. To solve a problem, one followed careful steps, start ing with formu lati ng a

hypothesis (a reasonable guess at a solution), continuin g through controlled observa-

tion and experimentation , moving to the formation of conclusions, and then, most

importantl y, communicat ing the whole process to oth er scientists.

The scientific method also compensated for the human frailties of individual

scientists. For example, Newton wrote serious commentaries about the biblical

book of Revelation, tried to vindictively destroy the careers of academic rivals, and

fudged some of the data in his Principia. With the scientific process, however,

human scientists applied the method to test his conclusions and produced better

PAGE 202.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:35:19 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

203

information about the natural world than had ever before been available in history.

Science had become such an essential part of the Western worldview that it forms

another basic principle:

Science is the only testable and generally accessible method

of understanding the universe; every other means of explana-

tion is opinion.

The Scientific Revolution had enormous consequences for Western civilization.

Science discovered reliable and reproducible answers about the workings of the

universe. Assuming that the secrets of nature could be revealed, scientists kept

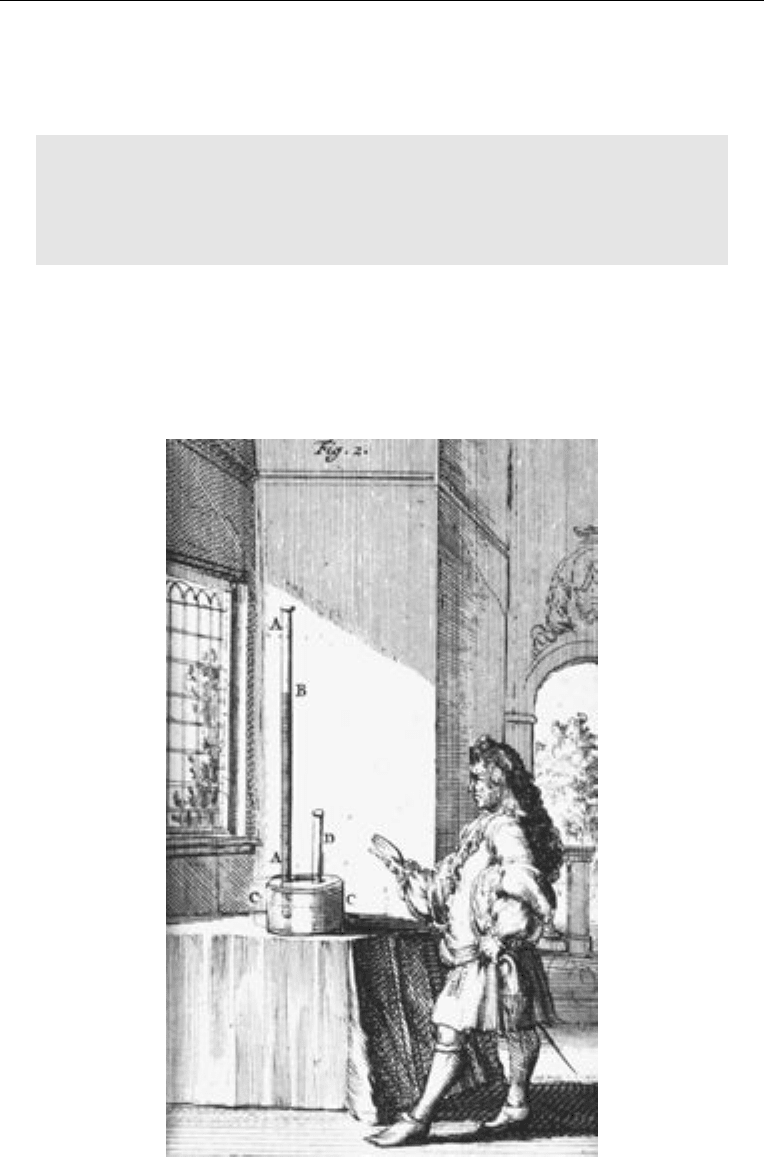

expanding their investigations and creating tools to help them (see figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. A seventeenth-century scientist

examines a barometer.

PAGE 203.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:35:31 PS

204

CHAPTER 10

One result was the acceleration in the invention of technology, namely the creation

of tools and machines to make life easier, safer, and more comfortable. Most people

in the world around 1600 lived much the same way as they had for several thousand

years. By the late seventeenth century, though, scientific academies (such as the

British Royal Society) institutionalized scientific inquiry and its application to eco-

nomic growth. Scientists were not mere theoreticians but innovators and inventors,

from thermometers to timepieces, pumps to pins. These inventions were soon

translated into the physical power used to dominate the globe. Medical and agricul-

tural advances based on science followed. By 1800, westerners were living much

more prosperous and comfortable lives, largely because of science.

The success of the Scientific Revolution was not complete or universal. Its atti-

tudes only slowly spread from the elites through the population. Many westerners

rejected the scientific mindset of skepticism toward traditional authorities because

of the importance of religion or the grip of superstition. Science does not answer

basic questions about the meaning of life and death. Honest scientists cannot pro-

claim certainty about the permanence of their discoveries: when presented with

new information, true scientists should change their minds. And theories can come

and go. For example, by the time of Newton, no reasonable scientist supported the

geocentric theory because too little evidence supported it and too much contra-

dicted it. Even the heliocentric theory has since been severely modified—while the

sun is the center of our solar system, it is certainly not the center of the universe. In

turn, Newton’s own theory of universal gravitation was rejected on some important

points (see chapter 13). By its nature, because of its many discoveries and regular

revisions, science has propelled Western civilization into constant change.

Review: How did the Scientific Revolution energize economics and society?

Response:

FROM THE SALONS TO THE STREETS

Historians have decided that 1687, the year of Newton’s Principia, marks the begin-

ning of a major intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment (1687–1789).

PAGE 204.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:35:31 PS

LIBERATION OF MIND AND BODY

205

During this time, scientific academies and universities adapted and spread many

scientific ideas. In addition, a few wealthy and curious women gathered a variety of

interesting people to discuss the issues of the day in their salons (pleasant rooms

in their fine homes). Beginning in Paris, salon hostesses such as Madame Goffrin

or Madame Rambouillet guided the witty conversation of clergymen, politicians,

businessmen, scientists, and amateur philosophers, writers, and popularizers

known as philosophes. The philosophes took what they learned, especially the

lessons of science, and publicized it.

Philosophes made Paris the cultural capital of Western civilization. For about a

century, French culture reigned supreme among the elites of the West. The French

language took over intellectual life and international communication, replacing the

Latin of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Europeans who wanted to seem

sophisticated imitated French styles of cuisine, clothing, furnishings, luxury goods,

and buildings. Salons and philosophes spread French taste across Europe. Along

the way, these intellectuals explained to society how new science and economics

impacted life. Four major concepts summarize their Enlightenment views: empiri-

cism, skepticism, humanitarianism, and progress.

The first of these concepts, empiricism, came from the starting point of sci-

ence: observations by our senses were both accurate and reasonable. Knowledge

obtained from studies of the natural world could consequently help explain human

activities. This effective idea contradicted many past religious authorities, who had

depended on divine revelation for their knowledge. Those supernatural, metaphysi-

cal, or spiritual answers were too open to dispute, too difficult to prove. Of course,

humans do not always draw the correct conclusions from their observations, nor

does the natural world always correspond to human experience. Regardless, philo-

sophes were convinced that applying the tools of science to human character would

help improve society.

One proponent of empirical thinking was John Locke of England. He proposed

that the human mind was like a blank slate, or tabula rasa, on which all learned

information was written. His most famous empirical argument justified England’s

Glorious Revolution (see below) toward more democratic politics. Locke argued

against books such as Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, in which religious perspectives

favored absolutism.

Another famous example of an empirical argument became the economic the-

ory called classical liberal economics. This theory contradicted the prevailing

theory of mercantilism, arguing instead for making capitalism ‘‘free-market’’ or lais-

sez-faire (as coined by contemporary French economists). Classical liberal theorists

justified their case on their observations of the behavior of peoples and institutions,

from smugglers to ministers of state, from banks to empires. They argued against

the theory of mercantilism, where government officials made key economic deci-

sions by granting monopolies and raising tariffs. Instead, they theorized that ratio-

nal individuals looking out for their own ‘‘enlightened’’ self-interest would make

better economic choices. The most famous formulation came from the Scotsman

Adam Smith in his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. He saw that individual

actions would accumulate to push the economy forward, as if collectively by a giant

PAGE 205.................

17897$

CH10 10-08-10 09:35:32 PS