Odersky M. Programming in Scala

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Section 12.6 Chapter 12 · Traits 261

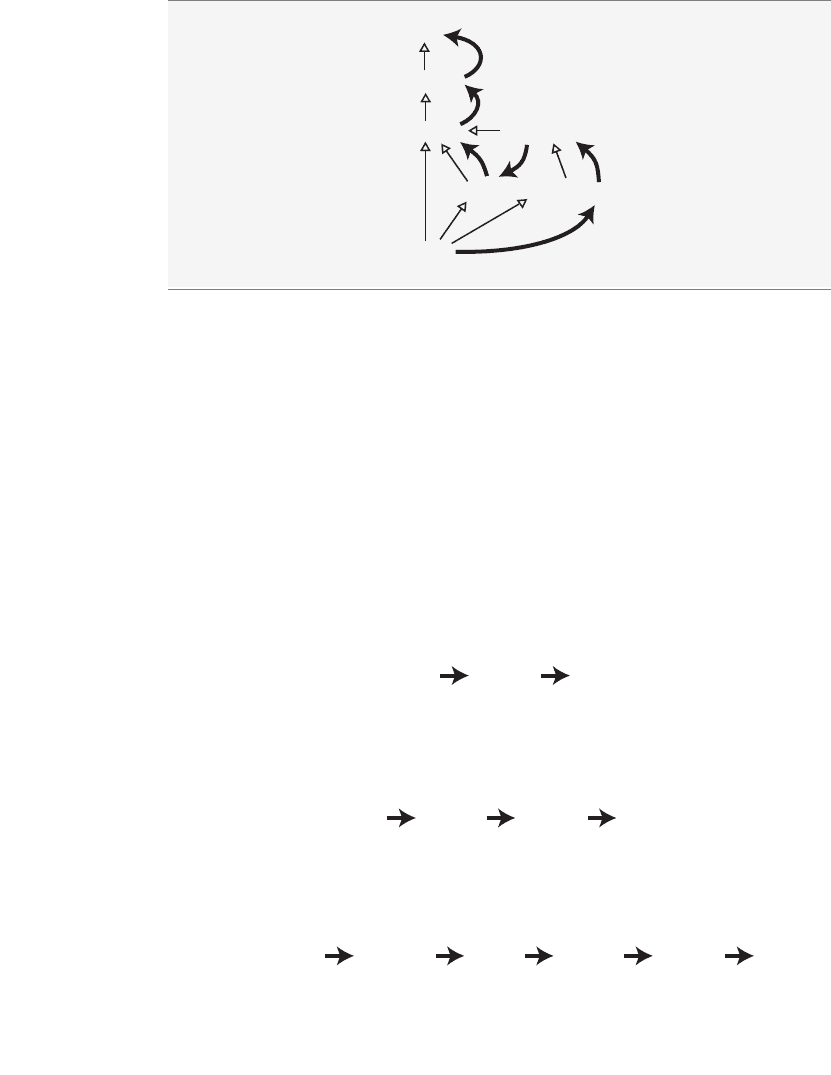

FourLegged

Cat

Furry

HasLegsAnimal

AnyRef

Any

Figure 12.1 · Inheritance hierarchy and linearization of class Cat.

pointing to the supertype. The arrows with darkened, non-triangular arrow-

heads depict linearization. The darkened arrowheads point in the direction

in which super calls will be resolved.

The linearization of Cat is computed from back to front as follows. The

last part of the linearization of Cat is the linearization of its superclass,

Animal. This linearization is copied over without any changes. (The lin-

earization of each of these types is shown in Table 12.1 on page 262.) Be-

cause Animal doesn’t explicitly extend a superclass or mix in any supertraits,

it by default extends AnyRef, which extends Any. Animal’s linearization,

therefore, looks like:

Animal AnyRef Any

The second to last part is the linearization of the first mixin, trait Furry, but

all classes that are already in the linearization of Animal are left out now, so

that each class appears only once in Cat’s linearization. The result is:

Furry Animal AnyRef Any

This is preceded by the linearization of FourLegged, where again any classes

that have already been copied in the linearizations of the superclass or the

first mixin are left out:

FourLegged FurryHasLegs Animal AnyRef Any

Finally, the first class in the linearization of Cat is Cat itself:

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 12.7 Chapter 12 · Traits 262

Table 12.1 · Linearization of types in Cat’s hierarchy

Type Linearization

Animal Animal, AnyRef, Any

Furry Furry, Animal, AnyRef, Any

FourLegged FourLegged, HasLegs, Animal, AnyRef, Any

HasLegs HasLegs, Animal, AnyRef, Any

Cat Cat, FourLegged, HasLegs, Furry, Animal, AnyRef, Any

FourLeggedCat FurryHasLegs Animal AnyRef Any

When any of these classes and traits invokes a method via super, the im-

plementation invoked will be the first implementation to its right in the lin-

earization.

12.7 To trait, or not to trait?

Whenever you implement a reusable collection of behavior, you will have to

decide whether you want to use a trait or an abstract class. There is no firm

rule, but this section contains a few guidelines to consider.

If the behavior will not be reused, then make it a concrete class. It is not

reusable behavior after all.

If it might be reused in multiple, unrelated classes, make it a trait. Only

traits can be mixed into different parts of the class hierarchy.

If you want to inherit from it in Java code, use an abstract class. Since

traits with code do not have a close Java analog, it tends to be awkward to

inherit from a trait in a Java class. Inheriting from a Scala class, meanwhile,

is exactly like inheriting from a Java class. As one exception, a Scala trait

with only abstract members translates directly to a Java interface, so you

should feel free to define such traits even if you expect Java code to inherit

from it. See Chapter 29 for more information on working with Java and

Scala together.

If you plan to distribute it in compiled form, and you expect outside

groups to write classes inheriting from it, you might lean towards using an

abstract class. The issue is that when a trait gains or loses a member, any

classes that inherit from it must be recompiled, even if they have not changed.

If outside clients will only call into the behavior, instead of inheriting from

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 12.8 Chapter 12 · Traits 263

it, then using a trait is fine.

If efficiency is very important, lean towards using a class. Most Java

runtimes make a virtual method invocation of a class member a faster oper-

ation than an interface method invocation. Traits get compiled to interfaces

and therefore may pay a slight performance overhead. However, you should

make this choice only if you know that the trait in question constitutes a per-

formance bottleneck and have evidence that using a class instead actually

solves the problem.

If you still do not know, after considering the above, then start by making

it as a trait. You can always change it later, and in general using a trait keeps

more options open.

12.8 Conclusion

This chapter has shown you how traits work and how to use them in several

common idioms. You saw that traits are similar to multiple inheritance, but

because they interpret super using linearization, they both avoid some of

the difficulties of traditional multiple inheritance, and allow you to stack

behaviors. You also saw the Ordered trait and learned how to write your

own enrichment traits.

Now that you have seen all of these facets, it is worth stepping back and

taking another look at traits as a whole. Traits do not merely support the

idioms described in this chapter. They are a fundamental unit of code that

is reusable through inheritance. Because of this nature, many experienced

Scala programmers start with traits when they are at the early stages of im-

plementation. Each trait can hold less than an entire concept, a mere frag-

ment of a concept. As the design solidifies, the fragments can be combined

into more complete concepts through trait mixin.

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Chapter 13

Packages and Imports

When working on a program, especially a large one, it is important to min-

imize coupling—the extent to which the various parts of the program rely

on the other parts. Low coupling reduces the risk that a small, seemingly

innocuous change in one part of the program will have devastating conse-

quences in another part. One way to minimize coupling is to write in a

modular style. You divide the program into a number of smaller modules,

each of which has an inside and an outside. When working on the inside

of a module—its implementation—you need only coordinate with other pro-

grammers working on that very same module. Only when you must change

the outside of a module—its interface—is it necessary to coordinate with

developers working on other modules.

This chapter shows several constructs that help you program in a modular

style. It shows how to place things in packages, make names visible through

imports, and control the visibility of definitions through access modifiers.

The constructs are similar in spirit to constructs in Java, but there are some

differences—usually ways that are more consistent—so it’s worth reading

this chapter even if you already know Java.

13.1 Packages

Scala code resides in the Java platform’s global hierarchy of packages. The

example code you’ve seen so far in this book has been in the unnamed

package. You can place code into named packages in Scala in two ways.

First, you can place the contents of an entire file into a package by putting a

package clause at the top of the file, as shown in Listing 13.1.

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 13.1 Chapter 13 · Packages and Imports 265

package bobsrockets.navigation

class Navigator

Listing 13.1 · Placing the contents of an entire file into a package.

The package clause of Listing 13.1 places class Navigator into the

package named bobsrockets.navigation. Presumably, this is the navi-

gation software developed by Bob’s Rockets, Inc.

Note

Because Scala code is part of the Java ecosystem, it is recommended to

follow Java’s reverse-domain-name convention for Scala packages that

you release to the public. Thus, a better name for Navigator’s package

might be com.bobsrockets.navigation. In this chapter, however, we’ll

leave off the “com.” to make the examples easier to understand.

The other way you can place code into packages in Scala is more like

C# namespaces. You follow a package clause by a section in curly braces

that contains the definitions that go into the package. Among other things,

this syntax lets you put different parts of a file into different packages. For

example, you might include a class’s tests in the same file as the original

code, but put the tests in a different package, as shown in Listing 13.2:

package bobsrockets {

package navigation {

// In package bobsrockets.navigation

class Navigator

package tests {

// In package bobsrockets.navigation.tests

class NavigatorSuite

}

}

}

Listing 13.2 · Nesting multiple packages in the same file.

The Java-like syntax shown in Listing 13.1 is actually just syntactic sugar

for the more general nested syntax shown in Listing 13.2. In fact, if you do

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 13.1 Chapter 13 · Packages and Imports 266

nothing with a package except nest another package inside it, you can save a

level of indentation using the approach shown in Listing 13.3:

package bobsrockets.navigation {

// In package bobsrockets.navigation

class Navigator

package tests {

// In package bobsrockets.navigation.tests

class NavigatorSuite

}

}

Listing 13.3 · Nesting packages with minimal indentation.

As this notation hints, Scala’s packages truly nest. That is, package

navigation is semantically inside of package bobsrockets. Java pack-

ages, despite being hierarchical, do not nest. In Java, whenever you name a

package, you have to start at the root of the package hierarchy. Scala uses a

more regular rule in order to simplify the language.

Take a look at Listing 13.4. Inside the Booster class, it’s not neces-

sary to reference Navigator as bobsrockets.navigation.Navigator, its

fully qualified name. Since packages nest, it can be referred to as simply

as navigation.Navigator. This shorter name is possible because class

Booster is contained in package bobsrockets, which has navigation as

a member. Therefore, navigation can be referred to without a prefix, just

like the code inside methods of a class can refer to other methods of that

class without a prefix.

Another consequence of Scala’s scoping rules is that packages in an inner

scope hide packages of the same name that are defined in an outer scope. For

instance, consider the code shown in Listing 13.5, which has three packages

named launch. There’s one launch in package bobsrockets.navigation,

one in bobsrockets, and one at the top level (in a different file from the

other two). Such repeated names work fine—after all they are a major rea-

son to use packages—but they do mean you must use some care to access

precisely the one you mean.

To see how to choose the one you mean, take a look at MissionControl

in Listing 13.5. How would you reference each of Booster1, Booster2, and

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 13.1 Chapter 13 · Packages and Imports 267

package bobsrockets {

package navigation {

class Navigator

}

package launch {

class Booster {

// No need to say bobsrockets.navigation.Navigator

val nav = new navigation.Navigator

}

}

}

Listing 13.4 · Scala packages truly nest.

// In file launch.scala

package launch {

class Booster3

}

// In file bobsrockets.scala

package bobsrockets {

package navigation {

package launch {

class Booster1

}

class MissionControl {

val booster1 = new launch.Booster1

val booster2 = new bobsrockets.launch.Booster2

val booster3 = new _root_.launch.Booster3

}

}

package launch {

class Booster2

}

}

Listing 13.5 · Accessing hidden package names.

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 13.2 Chapter 13 · Packages and Imports 268

Booster3? Accessing the first one is easiest. A reference to launch by itself

will get you to package bobsrockets.navigation.launch, because that is

the launch package defined in the closest enclosing scope. Thus, you can

refer to the first booster class as simply launch.Booster1. Referring to the

second one also is not tricky. You can write bobrockets.launch.Booster2

and be clear about which one you are referencing. That leaves the question of

the third booster class, however. How can you access Booster3, considering

that a nested launch package shadows the top-level one?

To help in this situation, Scala provides a package named _root_ that

is outside any package a user can write. Put another way, every top-level

package you can write is treated as a member of package _root_. For exam-

ple, both launch and bobsrockets of Listing 13.5 are members of package

_root_. As a result, _root_.launch gives you the top-level launch pack-

age, and _root_.launch.Booster3 designates the outermost booster class.

13.2 Imports

In Scala, packages and their members can be imported using import clauses.

Imported items can then be accessed by a simple name like File, as opposed

to requiring a qualified name like java.io.File. For example, consider the

code shown in Listing 13.6:

package bobsdelights

abstract class Fruit(

val name: String,

val color: String

)

object Fruits {

object Apple extends Fruit("apple", "red")

object Orange extends Fruit("orange", "orange")

object Pear extends Fruit("pear", "yellowish")

val menu = List(Apple, Orange, Pear)

}

Listing 13.6 · Bob’s delightful fruits, ready for import.

An import clause makes members of a package or object available by

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 13.2 Chapter 13 · Packages and Imports 269

their names alone without needing to prefix them by the package or object

name. Here are some simple examples:

// easy access to Fruit

import bobsdelights.Fruit

// easy access to all members of bobsdelights

import bobsdelights._

// easy access to all members of Fruits

import bobsdelights.Fruits._

The first of these corresponds to Java’s single type import, the second to

Java’s on-demand import. The only difference is that Scala’s on-demand

imports are written with a trailing underscore (_) instead of an asterisk (

*

)

(after all,

*

is a valid identifier in Scala!). The third import clause above

corresponds to Java’s import of static class fields.

These three imports give you a taste of what imports can do, but Scala

imports are actually much more general. For one, imports in Scala can ap-

pear anywhere, not just at the beginning of a compilation unit. Also, they

can refer to arbitrary values. For instance, the import shown in Listing 13.7

is possible:

def showFruit(fruit: Fruit) {

import fruit._

println(name +"s are "+ color)

}

Listing 13.7 · Importing the members of a regular (not singleton) object.

Method showFruit imports all members of its parameter fruit, which

is of type Fruit. The subsequent println statement can refer to name and

color directly. These two references are equivalent to fruit.name and

fruit.color. This syntax is particularly useful when you use objects as

modules, which will be described in Chapter 27.

Another way Scala’s imports are flexible is that they can import packages

themselves, not just their non-package members. This is only natural if you

think of nested packages being contained in their surrounding package. For

example, in Listing 13.8, the package java.util.regex is imported. This

makes regex usable as a simple name. To access the Pattern singleton ob-

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index

Section 13.2 Chapter 13 · Packages and Imports 270

Scala’s flexible imports

Scala’s import clauses are quite a bit more flexible than Java’s. There

are three principal differences. In Scala, imports:

• may appear anywhere

• may refer to objects (singleton or regular) in addition to packages

• let you rename and hide some of the imported members

ject from the java.util.regex package, you can just say, regex.Pattern,

as shown in Listing 13.8:

import java.util.regex

class AStarB {

// Accesses java.util.regex.Pattern

val pat = regex.Pattern.compile("a

*

b")

}

Listing 13.8 · Importing a package name.

Imports in Scala can also rename or hide members. This is done with

an import selector clause enclosed in braces, which follows the object from

which members are imported. Here are some examples:

import Fruits.{Apple, Orange}

This imports just members Apple and Orange from object Fruits.

import Fruits.{Apple => McIntosh, Orange}

This imports the two members Apple and Orange from object Fruits.

However, the Apple object is renamed to McIntosh. So this object can be

accessed with either Fruits.Apple or McIntosh. A renaming clause is

always of the form “<original-name> => <new-name>”.

import java.sql.{Date => SDate}

This imports the SQL date class as SDate, so that you can simultaneously

import the normal Java date class as simply Date.

Cover · Overview · Contents · Discuss · Suggest · Glossary · Index