Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further evidence of the impact of the general work climate was found by researchers

looking at the changing nature of public sector work. The project noted the range of

innovative initiatives in the workplace but also highlighted the positive contribution

that can be made by supervisors and managers.

Their perception of staff’s willingness to learn and need to learn may be influenced by factors

such as age, gender or the likelihood of career development. It is these line managers who con-

trol the immediate work environment and who control the flow of information about learning

opportunities. They hold the key to release from work, but also their encouragement or failure to

encourage can contribute to staff’s motivation to learn.

8

It becomes therefore difficult to separate how learning occurs without taking some

account of the relationship between employee and manager and the general climate of

the organisation.

In the past, organisations may have relied largely on the stability of the organisa-

tion’s structure for knowledge transmission. Managers would tend to know who to go

to for advice and would seek out the older and experienced employees who held the

‘know-how’. This knowledge and wisdom, accumulated over years of work, was a pre-

cious store of information. However, such a store was rarely formalised or articulated

and would be communicated only on an informal basis. Such ‘tacit knowledge’

9

would

be communicated to the next generation of employees and was an important part of

the organisation’s culture and socialisation process. Older employees were not only

useful as a source of knowledge but they would also be valuable steers for the younger

employee. Many held the role of an informal mentor and were much appreciated by

their younger subordinates. The following quote from a research study into hotel man-

agers’ attitudes aptly illustrates the point:

I think that in every department there was a good old stager who was willing to impart his knowl-

edge. It would really help me understand the processes and what made the organisation tick. He

just enjoyed talking about the business and I learnt such a lot. There does not seem to be the

time anymore.

10

Practices such as downsizing and outsourcing have had a major effect on this layer of

experienced employees. Not only are relationships disrupted by the restructuring of the

business, but also there is the potential for the complete destruction of this powerful

and important reservoir of knowledge and understanding.

Many organisations are now beginning to identify and formalise the significance of

knowledge and in some instances are creating universities at work. Motorola

University, for instance, is using learning programmes to drive critical business issues

and is attempting to constantly align training with the needs of the business. They see

learning as a key integrated component of Motorola’s culture.

11

Unipart is another

example of an organisation which has really driven the notion that learning should be

embedded within the workplace. They have set up a university, complete with a learn-

ing centre and development programmes. The university also has the structure and

support necessary for such a company-wide approach.

12

Distinct advantages are identified for those companies who are able to make effec-

tive use of their intellectual assets. The following quotation typifies the message:

The good news is that given reflection, focus and an appropriate and tailored combination

of change and support elements, effective knowledge management can enable corporate

renewal, learning and transformation to occur. Substantially more value can be created for

various stakeholders.

13

CHAPTER 10 THE NATURE OF LEARNING

395

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

This line of argument is supported by Nonaka

14

who argues that competitive advan-

tage is founded in the ability of companies to create new forms of knowledge and

translate this knowledge into innovative action. He says that ‘the one sure source of

lasting competitive advantage is knowledge’ and describes the different kinds of knowl-

edge that exist in organisations and the ways in which knowledge can be translated

into action. Nonaka calls knowledge which is easily communicated, quantified and

systematic explicit knowledge – the kind of information required for an IT system or a

new product. Tacit knowledge, however, is more akin to the wisdom described earlier –

inarticulate, understood but rarely described. Although more problematic, because it is

not so easily disseminated, tacit knowledge is arguably as important as explicit knowl-

edge. Those companies able to use both kinds of knowledge will make the creative

breakthroughs, according to Nonaka.

He suggests that the knowledge-creating companies systematically ensure that the

tacit and explicit feed into each other in a spiral of knowledge. Tacit knowledge is con-

verted into explicit knowledge by articulation and that explicit knowledge is used

within an individual’s cognitive understanding by a process of internalisation. Such

dynamic interplay of internal and external forces is supported by past learning the-

ories. Kolb’s

15

learning cycle (described in the next section) represents an alternative

cycle of thought and action and Piaget’s

16

theory of cognitive development combines

notions of internal processes (assimilation) and external adjustment (accommodation).

It perhaps is no surprise that ‘knowledge management’ has been the subject of hype

in the management literature and has been extolled as the route to the Holy Grail of

competitive advantage. Jeffrey Tan argues that managing knowledge is now the issue

for business in the 21st century. He suggests that:

A successful company is a knowledge-creating company: that is one which is able consistently to

produce new knowledge, to disseminate it throughout the company and to embody it into new

products or services quickly

17

Why knowledge management is important

Santosus and Surmacz

18

suggest that a ‘creative approach to knowledge management

(KM) can result in improved efficiency, higher productivity and increased revenues in

practically any business function’.

A substantial number of benefits have been identified by researchers of KM which

no doubt has contributed to the surge of interest. Kerr

19

identifies seven reasons why

KM is an important area:

■ business pressure on innovation;

■ inter-organisational enterprises (e.g. mergers, takeovers etc.);

■ networked organisations and the need to co-ordinate geographically dispersed groups;

■ increasingly complex products and services with a significant knowledge component;

■ hyper-competitive marketplace (decreasing life cycles and time to market);

■ digitisation of business environments and IT revolution;

■ concerns about the loss of knowledge due to increasing staff mobility, staff attrition

and retirements.

One of the key tricks therefore is for organisations to know how to share knowledge and

to learn from the experiences of others. Various interests and routes have drawn differ-

ent organisations to knowledge management; diversity in actual practices is broad. A

holistic approach is taken in the aerospace industry towards KM research. Kerr explains

that it is necessary to complement social with technological solutions for managing

knowledge in the engineering design process. Not only the know-why (design rationale

396

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

Creating new

forms of

knowledge

and reasoning – best practice) but the know-who (mapping expertise and skills) and

know-how (promoting communities of practice for learning in a dynamic context). The

Business Processes Resource Centre at Warwick University has distinguished four differ-

ent types of knowledge management practices:

■

Valuing knowledge: seeing knowledge as intellectual capital and recognising its worth.

■ Exploiting intellectual property: organisations which have a strong research and

development base may look for new and unconventional ways of using their exist-

ing knowledge base.

■ Capturing project-based learning: ensuring that knowledge gained from working on

one project is captured and made available for others to use.

■ Managing knowledge workers: recognising the needs of knowledge workers and

identifying new ways of managing to release creativity and positive outcomes.

20

(See

Chapter 12 for more details on motivating knowledge workers.)

Particular attention has been drawn to the use of information systems for capturing

knowledge and helping to multiply its effects. No longer the province of universities

and colleges, many different kinds of companies are involved in the management and

dissemination of knowledge. IT and in particular web-based technologies are the

engines of change.

Making use of knowledge

Many organisations are using the Web to share information and foster learning. Web

technology is changing the way in which people communicate and their expectations

of the scope, nature and type of knowledge and information. As Cohen has said:

Information no longer filters from the top down; it branches out into every imaginable direction

and it flows away from the information creators and towards information users. Employees can

now access information that was once only available to a few key people.

21

The move to using the Web network outside the organisation to communicate with

suppliers, customers and other firms has grown considerably.

22

Networked companies

are able to form linkages with partners and to have transparency about processes

which would not have been conceivable a decade ago. Changes in the way knowledge

is shared often comes hand in hand with other changes in the organisation. In the

Royal Mail traditional functional line structures were replaced with a spider’s web

design.

23

This had the impact of breaking down barriers between groups and allowing

new lateral relationships to be formed. A knowledge infrastructure was developed to

enable project information and learning to be captured. However, of key importance to

the success of this and other knowledge management projects is the willingness of

individual employees to participate and share their experiences. As organisations

become more and more dependent on each other, the need for effective procedure

becomes evident and with them the potential problematic issues of sharing of respon-

sibility, accountability and trust. The different process and ways of working can bring

their own stresses and problems. A full discussion of the impact of technology on

organisations is included in Chapter 17.

Although much recent management literature commends and encourages organisa-

tions to become learning organisations

24

and extols the benefits to be found in viewing

knowledge as an essential business asset, the work of ‘managing knowledge’ is not

without its difficulties. The truism that knowledge is power means that those people

within the organisation who wish to retain their power and control may feel very

CHAPTER 10 THE NATURE OF LEARNING

397

Problems of

managing

knowledge

disconcerted.

25

Some writers have produced kits to help organisations manage their

information

26

and offer advice. Others like Harrison

27

are sceptical about the ease with

which knowledge can be managed:

… knowledge develops in different ways in individuals and in organisations according to

processes and variables that are only imperfectly understood … No consensus has been reached

on how knowledge does in fact form, grow and change; or on the exact nature of the process link-

ing data, information and knowledge, or on the relationship between individual, group and

collective learning and how it can or does affect the knowledge base of an organisation, its com-

petitive capability, its performance or its advancement. (pp. 405–6).

The following challenges have been identified in KM initiatives to achieve business

benefits:

28

1 Getting employees on board – ignoring the people and cultural issues of KM and

not recognising the importance of tacit knowledge is a significant challenge (see sec-

tion below on why KMS programmes fail).

2 Allowing technology to dictate KM – while technology supports KM it should not

be the starting point. Critical questions about what, who and why need to be asked

before the how is put into place.

3 Not having a specific goal – there must be an underlying business goal otherwise

KM is a pointless process.

4 KM is not static – instead it is a constantly changing and evolving process as knowl-

edge has to be updated and stay abreast of current isssues.

5 Not all information is knowledge – quantity of knowledge does not equal quality

and information overload is to be avoided in organisations.

Malhotra

29

also sees challenges for knowledge management systems in ensuring that

the processes are aligned with external knowledge creation models. He suggests that

the enablers of KM systems may in the long term become constraints in adapting and

evolving systems for, and to, the business environment.

Different organisation sectors will have their own particular knowledge problems to

deal with and harvest. What constitutes intellectual property rights is a thorny issue

which universities are trying to resolve as their ‘knowledge’ is being sought by com-

mercial and industrial partners. The outsourcing of research and development into

universities is welcomed by many, but there are problems to be overcome not least in

terms of cultural conflict and ownership of ideas. Whereas academics would wish to

publish their research, industry would wish to maintain secrecy. Lack of awareness as

to the value of ‘knowledge equity relative to finance equity’ is a further difficulty as is

the ownership and protection of intellectual property. McBrierty and Kinsella present

ways in which some of the problems can be resolved and advance the many benefits

that collaboration between university and industry can bring to both parties.

30

The new term ‘knowledge management’ strikes a harmonious chord with the view of

people as human assets in an organisation. It captures the essence of people’s experience

and wisdom and declares that companies need to use the knowledge available to them.

For Harrison, communicating a coherent vision is a major principle for managing

knowledge productively. She believes that frequent dialogue and a culture which allows

challenge and innovation are crucial principles for benefits to occur.

31

Mayo

32

suggested

that five processes are necessary for an effective knowledge management system:

■ managing the generation of new knowledge through learning;

■ capturing knowledge and experience;

■ sharing, collaborating and communicating;

■ organising information for easy access;

■ using and building on what is known.

398

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

The success of many of these processes would depend on the culture of the organisa-

tion and its priority in sharing learning and knowledge. Many of the ideas and

concepts now being used in the new term ‘knowledge management’ have their roots in

the learning organisation.

So what does the term learning organisation mean? Peter Senge

33

defined it as a place:

where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new

and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and

where people are continually learning how to learn together.

Pedler, Boydell and Burgoyne’s

34

definition is one most often quoted:

an organisation which facilitates the learning of all its members and continuously transforms itself.

The learning organisation sounds ideal; the kind of company in which we might all like

to work! The picture that is painted is of an organisation that is ultimately highly flex-

ible and open-ended. It is able to continually transform itself and learn from experience

and thus always be ready to take advantage of changing external conditions. Such an

organisation values individual development, open communication and trust. It lends

itself to flat, open and networked structures. (See Chapter 15 for more information

about the impact of organisation structures on behaviour at work.) Rather than occur-

ring as separate and sometimes accidental activities, learning is a deliberate and central

process in the learning organisation. Joseph Lampel has identified five basic principles:

1 Learning organisations can learn as much, if not more, from failure as from success.

2A learning organisation rejects the adage: ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ as they are

constantly scrutinising the way things are done.

3 Learning organisations assume that the managers and workers closest to the design,

manufacturing, distribution and sale of the product often know more about these

activities than their superiors.

4A learning organisation actively seeks to move knowledge from one part of the

organisation to another, to ensure that relevant knowledge finds its way to the

organisational unit that needs it most.

5 Learning organisations spend a lot of energy looking outside their own boundaries

for knowledge.

Rather than claiming to be learning organisations, many suggest that they are working

towards becoming a learning organisation.

35

The outcome of the learning organisation is generally discussed as being positive,

indeed in some texts as being almost utopian. Garratt,

36

for example, views learning

organisations as essentially liberating and energising and as crucial for organisational

survival and growth. Burgoyne suggests that the learning company offers a new focus

for organisations and in particular identifies agenda items for HRM as a key contributor

of corporate strategic planning. He believes there are four new roles:

■ to continue to manage the employee stakeholder – but to view employees as cus-

tomers and partners;

■ to look for new stakeholders and develop new links and alignments particularly

with regard to development processes;

■ to be the focus of new organisation development (OD) initiatives and the source of

collective learning processes;

■ to inform policy formation and the implementation of strategy for the employee

stakeholder.

37

CHAPTER 10 THE NATURE OF LEARNING

399

THE LEARNING ORGANISATION

The learning organisation as a feature of OD is discussed in Chapter 22.

There is a growing body of literature which describes the ‘journey to become a learn-

ing organisation’. The three examples given in Table 10.3 are typical. Initially explaining

some of the difficulties different companies had in defining and measuring a learning

organisation, their ‘travel log’ then describes the decisions they made in pushing forward

their agenda for change. All produce qualitative and quantitative evidence to support

their decisions and to identify positive changes in their organisational culture.

If learning organisations help in the repositioning of HRM into a central strategic posi-

tion, the concept is, without doubt, to be welcomed by personnel professionals. In these

turbulent days, organisations are going to seize any practical help in coping with contin-

ual change. It is therefore no wonder that this concept is gaining increasing attention.

Some academics are concerned that the learning organisation concept has a number of

troublesome features in terms of application and rigour. For Garvin,

41

effective imple-

mentation will need the resolution of three critical issues:

■ meaning (or definition)

■ management (or practical operational advice)

■ measurement (tools for assessment).

Although he believes that the learning organisations ‘offer many benefits’, he raises

concerns about unanswered questions:

■ How, for example, will managers know when their companies have become learning

organisations?

■ What concrete changes in behaviour are required?

■ What policies and programmes must be in place?

■ How do you get from here to there?

Harrison

42

also critically comments on the ‘looseness’ of the learning organisation con-

cept and points out that the sum of the learning of individuals does not necessarily

equal organisational learning. Processes and systems are required to effectively utilise

individual learning. Mumford

43

suggests that it is:

impossible to conceive of a learning organization, however defined, which exists without individ-

ual learners. The learning organization depends absolutely on the skills, approaches and

commitment of individuals to their own learning.

400

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

Organisation Steps taken Outcomes

Club 24

38

Stairway initiative: Morale higher

Experiential learning Attendance and efficiency

programme for the improvement

‘Collection Department’ Change in culture

English Nature

39

Benchmarking Raise awareness of different

methods of learning

Introduction of range of

programmes designed to

strengthen the links between

learning and action

Reviewed support given to

projects and funding

Hay Management Cultural audit Strengthened focus on clients

Consultants

40

Increase in teamwork

Table 10.3 Learning experiences of different companies

Difficulties

with the

learning

organisation

comcept

Furthermore he contends that individuals are empowered to take control of their own

personal destiny by being given opportunities to learn. Although empowerment may

occur for some, Harrison argues that control of learning and the power base of organ-

isation is still tightly guarded and controlled. She suggests that any radical questioning

of organisations would be regarded as a real challenge to the management norms.

Coopey

44

believes that there are serious gaps in the learning organisation literature.

He claims that writers have ignored the importance of control and political activity

within organisations. He criticises the unitary view that is taken and the elitist model

that is put forward. He points to research which shows that, in turbulence, political

action increases and concludes that the learning organisation may be destined to be a

mechanism of management control which will ‘advantage some, but disadvantage

others’. The effect of differential power, he believes, diminishes the potential for indi-

vidual and collective learning.

Structure and culture of the organisation

The importance of politics within organisational structures is discussed by Salaman and

Butler who argue that managers may resist learning. They claim that such resistance

may arise from different sources:

It may derive from the organization’s structure and culture, from the way the organization is dif-

ferentiated into specialisms, from pathologies of teamwork, and even from individuals

themselves. At the organisational level, the most significant factor concerns the way in which

power is exercised, and the behaviours that are rewarded and penalised.

45

It would seem that the journey towards the learning organisation might be a voyage

without an end. Even Garratt voiced his worries about the possible problems that

emerge with directors saying and doing different things:

Paradoxically, top managers now mouth the words ‘our people are our major asset’, but do not

behave as if this is so.

46

He suggests that for an organisation to create a climate in which learning is possible,

there has to be a willingness on the part of the senior managers to accept that learning

occurs continuously and at all levels of the organisation. Allowing information to flow

where it is needed may well be politically difficult, but no doubt a most critical meas-

ure of an organisation’s effectiveness. Developing the capabilities of leadership in a

learning organisation has led Garratt to propose six stages in the development process

of a senior manager:

1 Induction – the introduction of newcomers to the workplace, colleagues, work itself;

2 Inclusion – a subtle but critical process – involving the acceptance and inclusion of

the manager within the group;

3 Competence – technical skills being dependent upon the extent to which a man-

ager is included;

4 Development – the stage at which creativity and personal development merge;

5 Plateau – an ‘idyllic stage’ at which competence is high and everything is going well;

6 Transition – the move towards another role.

Mayo suggests that organisations should benchmark their company and diagnose

actions that need to be taken to become learning organisations.

47

The index Mayo has

designed illustrates the complexity of the journey. Companies seriously wishing to

become learning organisations need to consider ‘the enablers’ – who/what will support

the culture (policy and strategy; leadership; people management processes; informa-

tion technology) and the impact of learning at a personal, team and organisational

CHAPTER 10 THE NATURE OF LEARNING

401

Politics and

control

Emphasis

on people

development

level. The final measure focuses on the outcome from learning and the value that is

added to the business.

Mayo’s measure reinforces the power and centrality of learning. Some ways of

behaving are embedded in organisations appearing institutionalised. Rules, routines

and procedures can become fixed and automatic. Knowledge of the organisational cul-

ture is a critical factor in understanding the extent to which learning is valued. Some

organisational structures are more likely to encourage trust, openness and creativity

than others; and some organisations may invest more in communication systems and

support networks. The type of human resource strategies and policies are also pertinent

in encouraging a learning climate. Do employees feel their efforts to learn and develop

are rewarded? Are employees encouraged to be creative and innovative? If so, how? Are

employees fearful of making mistakes? Or, do they care?

So far in this chapter we have looked at the macro picture of learning in organisa-

tions, but learning has to start with the individual. How do individuals learn? What is

the process of learning? Can we discern differences in the process if we focus on what is

learned – behaviour, knowledge, and attitudes? What impact does personality and tem-

perament, ability and culture have on the process of learning? In this part of the chapter

we will consider the interaction between learning and other aspects of the individual’s

psyche. Styles of learning may have clear links to personality type, to intelligence and to

motivation. Can people, for instance, learn to become more emotionally intelligent?

Psychologists interested in linking personality to learning style have found, for ex-

ample, that introverts and extroverts differ with respect to their reactions to punishment

and reward.

48

Studies using the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator also reveal differences in

learning preferences for their 16 personality types.

49

(See later in this chapter.)

Application of learning styles to managerial behaviour has been advanced by the

work of Kolb

50

and Honey and Mumford.

51

These studies have demonstrated how varia-

tions in individuals’ preferred learning styles influence the learning process (see later

section for more details).

An effective manager fosters learning that leads to competent behaviour and perform-

ance. Knowing how information and wisdom can be stored and accessed in the

organisation and developing processes that can lead to stimulating learning events is

an important part of a manager’s role and an essential element of an organisation’s

future health. Theories of learning can act as frameworks for managers to help in the

identification and analysis of problems. Thus understanding theories and models of

learning can be helpful for managers in diagnosing problems and helping them to set

new actions.

The early classic studies, to be examined first, offer explanations for simple learning

situations. The principles arising from these laboratory experiments remain applicable

to an understanding of organisational behaviour. The effects of rewards and punish-

ment (the ways in which behaviour can be shaped and modified) have considerable

relevance in understanding the motivation of individuals and the culture of organisa-

tions. These are called behaviourist theories.

Dissatisfaction with the earliest theories led researchers to consider more complex

learning situations. ‘Cognitive theories’ have particular application to an understand-

ing of individual differences in learning situations. They offer models which explain

the process of learning and take into account different preferences and styles.

402

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

HOW DO PEOPLE LEARN?

Theories of learning have their roots in the history of psychology and some of the earli-

est experimental psychologists focused their attention on animal learning. These

theorists based their ideas on the positivistic tradition and were keen to develop laws of

learning. They were only interested in behaviour which could be objectively measured

and they designed experiments which maximised key scientific conditions: control,

reliability and validity. A school of psychology called behaviourism developed out of

these early research studies. As the name suggests, researchers were interested in the

study of behaviour and those actions which could be observed, measured and con-

trolled. Ideas and thoughts in people’s minds were considered inaccessible to objective,

scientific measurement and were therefore excluded from study.

The following principles of learning were developed by the leading behaviourists:

Law of exercise and association J. B. Watson

Theory of classical conditioning I. Pavlov

The outcomes of learning E. Thorndike

Theory of operant conditioning B. F. Skinner

J. B. Watson developed the law of exercise and association. This refers to the process

which occurs when two responses are connected together and repeatedly exercised.

Watson was particularly interested in the study of fixed habits and routines.

52

To what extent are organisations built on habits and routines? Studies of organisa-

tional culture illustrate the power of habits and the acceptance of ways of behaving.

For some individuals, these behaviours become ‘locked-in’ and are seen to be ‘the only

way’ of completing certain tasks; it is as if they are fixed into beds of concrete. Such

habits are hard to break and yet keeping behaviour flexible is one of the objectives of

the learning organisation.

Speech can also be subject to habits and routines. Messages of greetings are illustra-

tive of such regularity. The predictability of the message gives some comfort and is

often symbolic of recognition. When people say ‘How are you?’ they do not expect to

be given a run down of your medical history. The rhetorical question is really saying

‘Hello – I see, acknowledge and recognise you’.

Classical conditioning

Pavlov,

53

working in Russia, developed a theory called classicalconditioning. His labora-

tory experiments demonstrated how instinctive reflexes, such as salivation, could be

‘conditioned’ to respond to a new situation and a new stimulus. The ‘normal’ and

physiological reaction to food is the salivation response. Pavlov found that by combin-

ing food with a new stimulus, the dogs under study would salivate to the new stimulus

if it were repeatedly associated with the food. Pavlov used a variety of stimuli (bells,

tones, buzzers) and found that the dogs could be conditioned to salivate to the sound

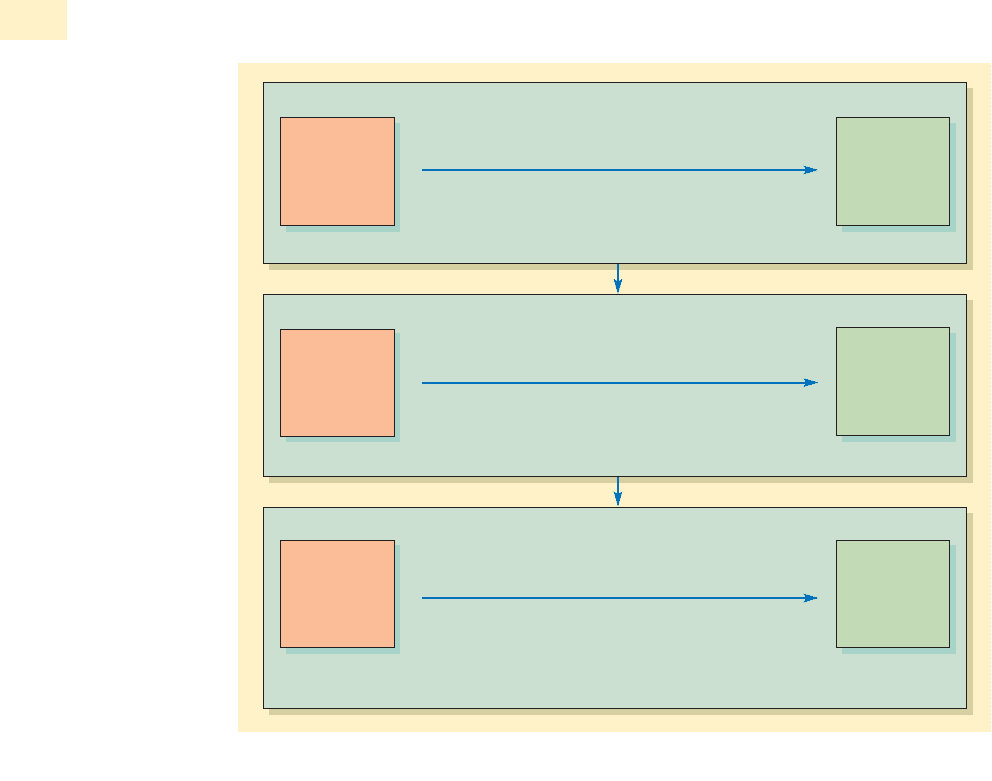

of one of these stimuli, even when no food appeared. (See Figure 10.2.)

Pavlov through his repeated experimental studies showed the power and strength of

association. The experimental dogs would salivate at the sound of the bell, an ‘unnatu-

ral’ stimulus. Pavlov varied his investigations to find out the extent of his control over

the dogs’ salivation response. He discovered, not surprisingly, that the response could

be strengthened if the stimulus was constantly repeated with the response and would

diminish to extinction level without repeated connection. Pavlov also showed that

CHAPTER 10 THE NATURE OF LEARNING

403

BEHAVIOURISM

Exercise and

association

dogs would remember their learning after a peroid of time So, after a break, those dogs

that had gone through the experiments were faster at learning the association than

dogs new to the experiment. He also discovered that dogs could learn to discriminate

between tones of bells and salivate to some but not others. In other trials he found that

dogs could be conditioned to generalise to other similar sounds.

How can we relate these experiments on dogs to behaviour at work? There are

times when our body responds more quickly than our mind. We may have an initial

panic reaction to a situation without necessarily realising why. Physiological reac-

tions may be appropriate in times of stressful situations – our body may be in a state

of readiness to run (fight or flight reaction).

54

At other times our reactions may be

‘conditioned’ because of previous associations of pain, guilt or fear. Smells and

sounds are particularly evocative and may release physiological reactions akin to the

Pavlovian experiments. Thus sitting in a waiting room at the dentist’s and hearing

the sound of the drill may invoke an increase in our blood pressure or heart rate –

nothing to do with any actual pain we may be experiencing. Returning to school for a

parents’ evening may invoke feelings of ‘dread’ or ‘pleasure’ depending on our own

childhood experiences of school and its associations. Training for some occupations

may depend upon learned associations and automatic reactions such as initial mili-

tary training. If fire drills are to be successful, immediate reaction to the bell or siren

is essential.

404

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

Stimulus (S)

Plate of

food

Stage 1: Pre-learning

Stimulus (S)

Plate of food

Plus

The sound of

a bell

Stage 2: State of learning

Stimulus (S)

The sound

of a bell

(no food)

Stage 3: S–R bond has been formed and learning has taken place

No learning – an automatic and instinctive salivation response to the sight of food.

Repeated over many trials the dog begins to associate the bell with the sight of food.

The dog has been conditioned to respond to the sound of the bell even though no food

appears.

Response (R)

Dog

salivates

Response (R)

Dog

salivates

Response (R)

Dog

salivates

Figure 10.2 Classical conditioning