Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1 Career management programme

Citibank reports that intensive training placements in other countries are effective in

attracting and retaining the best people. The paper reports that companies which do

not have career management programmes can experience staff turnover rates in excess

of 15–20 per cent. Management programmes can be passive, e.g. include regular per-

formance reviews and setting performance goals, whereas active programmes consider

overseas postings, in-house training. The most successful programmes are those which

require employees to plan their own careers. The paper claims that Singaporean and

Hong Kong companies are not as flexible as organisations in Australia and New

Zealand in enabling individuals to design their own plans.

127

2Traditional processes preferred at Nestlé

Nestlé re-examined career management systems and decided the following critical suc-

cess factors for their culture:

■ a transparent process owned by the line manager;

■

information about managers’ career expectations and the needs of the organisation;

■ measurement standards to determine whether it was working.

In setting up the process they concentrated on focused succession planning and intro-

duced career management groups. These groups review the needs of the organisation

and define the menu of experiences future managers will need. The system is now

more focused and measurable. They decided not to introduce self-development, men-

toring and career workshops, believing that the impact would be limited.

128

3 Changing expectations

The starting point for SCO, a software company, was to change the expectations of the

employees away from traditional ideas about career progression, to ones that were

more realistic and possible. They decided on four parameters to realign individual goals

and the organisation direction:

■ building a learning culture through self-development and career management

driven by the individual;

■ improved feedback and communication;

■ effective performance management system;

■ increasing the ability of individuals to bring about change.

Practical interventions included:

■ self-development guide – of inventories and activities;

■ career management workshops;

■ project teams for specific business issues;

■ technical problem-solving workshops;

■ lunchtime training on key issues;

■ workshops on managing transition;

■ review of performance management systems.

129

4 Mentoring and networks

Used now by many organisations, benefits include developing skills in reflection and

evaluation, self learning and development. Some organisations initiate formal mentor-

ing programmes with regular one-to-one advice and guidance with an older successful

role model. Aspiring managers can gain much-needed exposure and visibility.

Telementoring has also been suggested as a method of developing and supporting indi-

viduals when face-to-face meetings are not possible.

130

Women’s networks can provide a communication channel enabling contact, sharing

information and reducing isolation. Although there are professed benefits to be gained

McDougall and Briley noted that in 1994 few organisations used mentoring or networking

as a means of developing women and where it was used it was on an informal basis.

131

CHAPTER 9 INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

375

5 Development centres

Development centres which have as their aim to provide opportunities for reflection

and development have been widely commended for their benefits. The Peer Centre

designed at Roffey Park has its focus on learning: how to coach, how to observe, how to

give feedback constructively and how to plan development at an individual and group

level. They believe it sends strong signals to employees that they are valued, they are

being offered a coherent alternative to continual promotion.

132

In short, organisations need to consider ways in which they can establish a broader de-

gendered view of careers, one that takes into account the ebbs and flow of individual

needs at different stages of their work cycle. A programme that allows individual to

reflect, re-tool and re-energise; one that allows for greater involvement in families or

communities outside work.

Changes in the way organisations are structured and managed may be good news for a

more feminine style of leadership. (See Chapter 10 on learning.) If the effectiveness of

organisations requires a style which is facilitative and participatory, this should augur

well for women who prefer the more social, less hierarchical modes of management.

Changing ideas on leadership

There is support for the view that flexible forms of organisations are encouraging a

new way of constructing management and leadership in less masculine ways than has

traditionally been the case. Themes such as identity, cohesion teams and social integra-

tion all suggest a non-masculine direction. ‘If more participatory, non-hierarchical

flexible and group-oriented style of management is viewed as increasingly appropriate

and this is formulated in feminine terms then women can be marketed as carriers of

suitable orientations for occupying positions as managers.’

133

A decade ago Judy Rosener identified an interactive leadership style in the female

managers that she studied. She found that these women ‘actively work to make their

interactions with subordinates positive for everyone involved’. Specifically she

described four characteristics of this style:

■ Encourage participation – by making people feel part of the organisation, instilling

group identity and facilitating inclusion and participation in all aspects of work.

■ Share power and information – willingly sharing power and information rather

than guarding and coveting it. They are not preoccupied with ‘the turf’.

■ Enhance the self-worth of others – by not asserting their own superiority and

giving credit, praising publicly and recognising individual efforts. Most disliked

practices that set them apart from others (separate parking/dining etc.).

■ Energise others – by being enthusiastic for the work and encouraging others to see

work as challenging and fun.

134

Research conducted by Alimo-Metcalfe

135

supports the view that the modern style of

leadership required for organisations is one that embraces vision, individual considera-

tion, strengthening participation and nurtures growth and self-esteem. Alimo-Metcalfe

was positive that women managers were bringing with them real qualities of ‘warmth,

consideration for others, nurturance of self-esteem and above all, integrity’. In a later

article leadership is described as not about being a wonder woman (or man) but as

someone who:

376

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

LEADERSHIP, MANAGEMENT AND WOMEN

A pull towards

a more

feminine style

■ values the individuality of their staff;

■ encourages individuals to challenge the status quo;

■ possesses integrity and humility.

She claims that myths of leadership are dangerous because they suggest that leadership

is rare, found mainly at the top of organisations and is about being superhuman.

136

This she claims distinguishes her study from those from the US which tend to focus on

‘distant leaders’. The characteristics of the distant leader may be different to those

valued in ‘nearby leaders – the immediate line manager’. Although vision, charisma,

courage are qualities that are ascribed to the distant leader subordinates seek qualities

in their nearby leader such as being sociable, open and considerate. These were rated

more highly in their research and it was found that women scored higher than men in

11 out of the 14 characteristics.

However, the interest in ‘New Leadership’ research and transformational leadership in

particular has focused on ‘heroes’ and the nature of charisma. Many studies have

focused on public figures, notably men. Goffee and Jones claim that inspirational leaders

share four unexpected qualities:

■ They selectively show their weaknesses.

■

They rely heavily on intuition to gauge the appropriate timing and course of their actions.

■ They manage employees with tough empathy.

■ They reveal their differences; they capitalise on what is unique about them. However,

Goffee and Jones suggest that gender differences can lead to stereotyping and to a

double bind situation. They suggest that women may opt to ‘play into’ their stereo-

type and make themselves invisible ‘by being more like the men’ or deliberately play

the role of nurturer or set themselves apart by campaigning for rights in the work-

place. Whichever route is chosen females are playing into a negative stereotype.

Goffee and Jones ask the question ‘Can female leaders be true to themselves?’

137

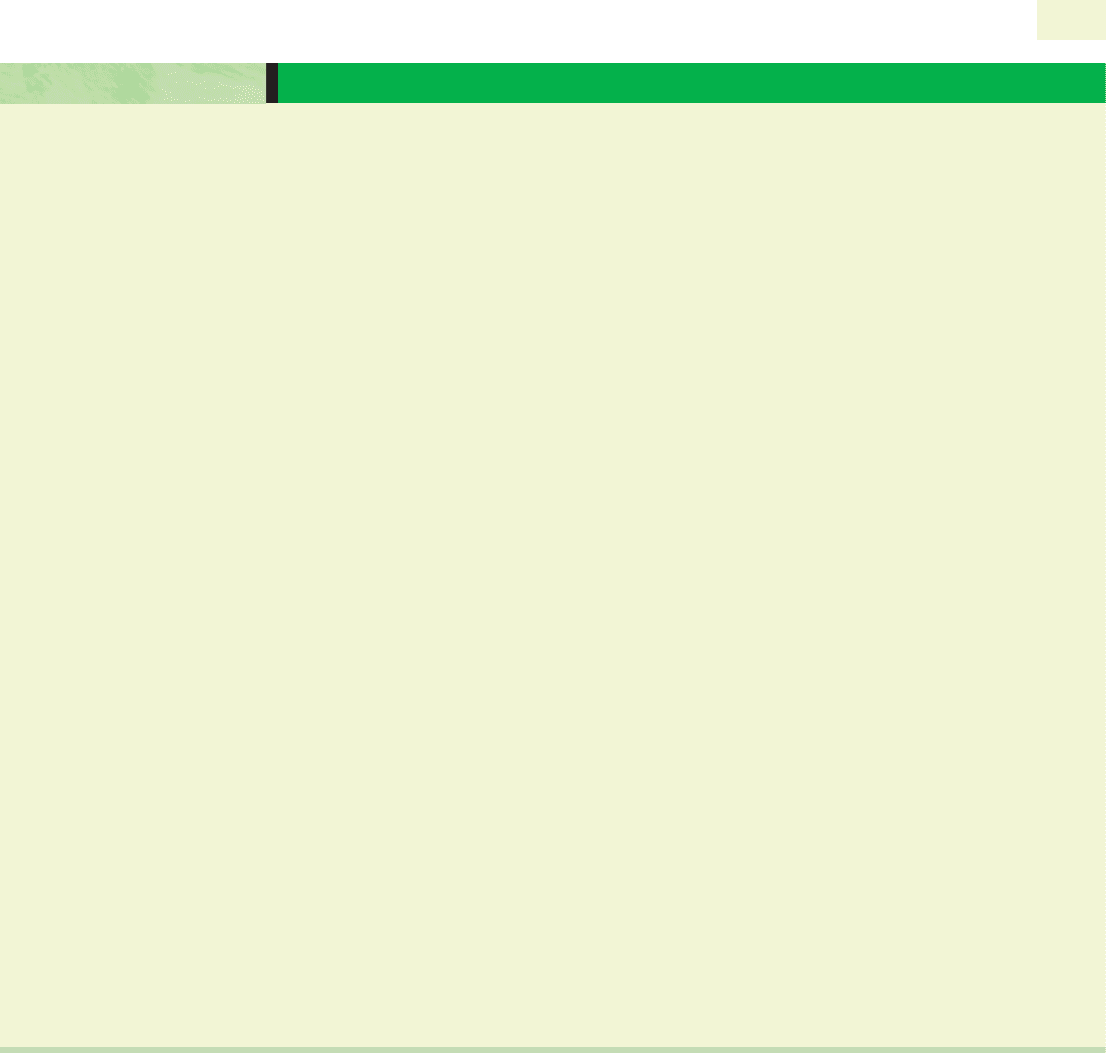

The extent to which women’s experiences and skills offer something different to

men is still in debate but there is a clear push in the literature concerning the signifi-

cance of skills and qualities associated with being feminine. These dimensions resonate

with the changing nature of organisations in the 21st century and support the notion

of emotional intelligence. Alvesson and Due Billing, working in Sweden and Denmark,

have summarised the differing and at times confusing approaches in the framework

shown in Figure 9.8. In addition to the arguments on gender similarity (or not), they

also consider the impact of differing organisational approaches. They argue that the

notion of feminine leadership may not be especially valid or useful. Workplaces, which

are organised without the stereotyping of gender, might evolve new and more effective

models of leadership.

138

What should organisations do to encourage women leaders?

Alvesson and Due Billing suggest that there are three agendas which require attention:

■ Short agenda – To advocate ensuring women have same privileges as men: equal

pay, access etc.

■ Long agenda – To strengthen women’s self-confidence and facilitate the integration

of work and family.

■ Broad agenda – To emphasise women’s interests and female values with broader

concerns. The consideration of women-focused activities in relationship to men.

The social relations between men and women and the gendered nature of institu-

tions would be of central concern. How the organisation reaffirms gender positions

in its culture; its stories, rites and rituals.

CHAPTER 9 INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

377

A push to

maintaining

status quo:

male as leader

In addition organisations could:

■ help to demystify leadership and identify the competencies within the organisation

to which it is to be applied;

■ develop the importance of feedback and reflection – evidence suggests that success-

ful leaders thrive on feedback and support. Provide structures to enable feedback

and reflection time – ‘time to think’. Kline advocates that organisations should

become thinking environments as everything we do depends for its quality on the

thinking we do first, and our thinking depends on the quality of our attention for

each other. A thinking environment says ‘you matter’.

139

Reviews and articles explaining the position and status of women typically conclude

with exhortations to organisations to introduce and promote schemes which would

positively help and support women. The logic of introducing such schemes is based on

good business sense in that women represent an untapped human resource. There has

been considerable media hype about the progress of women at work and yet this is not

revealed in the latest statistics. Improving the ‘lot’ of women can also provoke resent-

ment from men.

Perhaps the most positive approach to take is for an organisation to acknowledge

the changing working pattern of all employees and to consider the best working prac-

tices for managing a diverse workforce. This should not be done mechanically but by

analysis of the organisation and its workforce. Organisations need to analyse, con-

sciously debate and question their unwritten assumptions and expectations in order to

reveal prejudices inherent in the culture of their organisations. Analysis of the way in

which culture is expressed in all its trivial detail would lead to an understanding of per-

378

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

Ethical/political concern

(equality, workplace humanisation)

Equal opportunities

Low proportion of women

managers reflection of

inequalities that exist.

Alternative values

This position stresses the

differences and conflicts

between men and

women.

Meritocracy

Potential talents of

women need to be

recognised for the

organisation’s

effectiveness.

Special contribution

Women can make a

‘special contribution’

to management because

of their feminine

perspective.

Emphasis on

gender similarity

Emphasis on

gender difference

Concern for

organisational efficiency

Figure 9.8 Matrix indicating differing perspectives on gender

(Source: Adapted from ‘Approaches to the Understanding of Women and Leadership’ in Understanding Gender and Organisations by

Alvesson, M. and Due Billing, Y. Reproduced with permission from Sage Publications Ltd, 1997.)

POSITIVE APPROACHES

ceptions and attitudes. Until a full analysis is completed it remains doubtful if more

egalitarian practices will develop.

Employees should go through a three-stage process of auditing existing policies, set-

ting measurable goals and making a public commitment from top management to

achieving them. A number of agencies see work/life balance (discussed in Chapter 18) as

key to equality for women and men.

140

Equality Direct’s appeal is to the ‘bottom-line’:

Businesses prosper if they make the best use of their most valuable resource: the ability and

skills of their people. And these people, in turn, will flourish if they can strike a proper balance

between work and the rest of their lives.

141

Why do we need a work/life balance?

The EOC claims there ‘is now a mismatch between people’s caring and parenting

responsibilities and the demands of inflexible employment patterns’ (p. 1).

142

Family

patterns are more fluid and diverse requiring work environments to reflect people’s

changing needs. Most two-parent families are also two-earner families. There are more

lone parents, more than half who work.

143

The government has made a commitment to

enhancing choice and support for parents including enhancing access to good quality

child care and parenting services; tailoring financial support to families’ circumstances

and working in partnership with business to promote the benefits of flexible working. A

number of current government agencies are urging organisations to develop more flex-

ible working practices.

They argue that if employees are given greater control and choice over where, when

and how much time is in work, a more satisfied, valued, committed and less stressed

workforce will result. The notion is that everybody, regardless of age, race and gender,

will prefer to work to a rhythm of work that suits his or her lifestyle. The challenge of

managing caring responsibilities and paid employment are too often a source of stress

and anxiety. Evidence from research studies has shown the dysfunctional impact that

the ‘long hours’ culture prevalent in Britain has on employees’ home life.

144

This new focus on equality has moved from one that is focusing only on women’s

needs to one of inclusiveness. It is a compelling idea as it avoids the difficulties of hos-

tility and resentment potentially caused by the selective focus on women’s needs.

Rather than being a ‘women’s issue’ it suggests that gender should be ‘mainstreamed’;

it should be a core practice of the business. The EOC identify that mainstreaming

requires rethinking the traditional roles of men and women in society:

Simply, the gender mainstreaming approach means challenging our assumptions and stereo-

types about men and women, and their roles in society and the economy. It means making

evidence-based policy. This is simply good sense. Well-targeted policy which takes account of the

different ways men and women may organise their time, or relate to goods and services, means

better use of resources and better outcomes in terms of achieving policy objectives. In the

process social and economic inequalities will be challenged.

146

CHAPTER 9 INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

379

The push for flexibility

In a report commissioned by the CIPD entitled ‘Married to the job’ one in three partners of

people who work more than 48 hours in a typical week said the long hours have an entirely

negative effect on their personal relationship and on the relationship with chidren. The long-

hours workers themselves feel they have struck the wrong work/life balance and feel guilty

that they are failing to pull their weight on the domestic front. Working long hours can have

a negative effect on job performance and cause accidents. CIPD reports 41 per cent of man-

agers believe that the quality of their working life has deteriorated over the past three years.

Those working in small firms are the most confident about the quality of their life.

145

Is work more attractive than home?

Research conducted in the US by Hochschild noted that attractive organisations can be

‘seductive’. In her study she observed that it was possible to achieve fulfilment, satisfac-

tion, care and confirmation at work, while home shared similarities to a ‘Taylorised’

environment. In such circumstance work becomes home, and home becomes work. This,

she claims offers one explanation why parents choose not to take up the family-friendly

(FF) schemes offered in the company as they actually prefer to be in work.

147

Swedish experience suggests that women will initially take more advantage than men of

FF policies and that many men will continue to behave as if married to a full-time house-

wife. However, some recent research suggests that this at last is beginning to change and

that a new model of a more democratic family may be evolving in Sweden.

148

Approaches to gender equality: a comparison

A study conducted in Australia explored the link between different EO policies and the

number of women in management positions. This identified four types of approaches:

■ Classical disparity – equal treatment practised but gendered roles assumed;

■ Anti-discrimination – equal outcomes encouraged;

■ Affirmative action – assistance for disadvantaged groups and specific actions taken

(women’s groups/networks/mentoring programme for women, formal mechanisms

exist with women);

■ Gender diversity – compensate for disadvantages through a change in culture and

organisational systems – flexible systems encouraged – but specific treatment for one

group discouraged, for example, job sharing, part-time work.

The study found that those organisations that took an affirmative action approach

had significantly higher numbers of women in all management tiers. Organisations

classified as gender diverse did not see such significant increases. French states, ‘One

possible explanation as to why this might be involves the fact that broad application of

diversity strategies results in limited practical outcomes. That is, in trying to do every-

thing, nothing substantive is achieved. Another explanation is that the diversity

approach to substantive equity may take up to 25 years because of the slow pace of cul-

tural and structural change without the use of direct affirmative action strategies.’

149

There still seems to be some way to go before flexible working practices become part

of our ‘normal way of life’. In reality it would seem that the political and cultural nature

of the organisation is a major factor in choosing working practices. It appears that there

is a stigma attached to employees who choose to work part-time and people fear that if

they choose to work at home they may miss out on potential promotion opportunities.

The following obstacles stand in the way of a healthy work/life balance:

■ Family-friendly schemes are still perceived as concessions to women.

■ Men’s domestic absenteeism.

■ Presenteeism (being seen at work) as a phenomenon linked to career success.

Only time will tell whether the exhortations will work. Will there be stigma

attached to employees who choose to work part-time? Will people who choose to work

at home miss out on potential promotion opportunities? Are there preferred career

tracks, which exclude routes other than the traditional linear paths? So, even if the

opportunities are open to all, in reality the political and cultural nature of the organi-

sation prevents career-hungry individuals from choosing such options. (Please see

Chapter 22 for more detail on the working of cultural processes in organisations.)

380

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

■ The individual member is the first point of study and analysis in organisational

behaviour. One of the essential requirements of organisations is the development and

encouragement of individuality within a work atmosphere in which common goals and

aims are achieved. Emphasising individual differences and valuing diversity is a recent

catalyst for helping the equality agenda in business. One of the distinguishing factors of

successful managers in any organisation is their ability to bring out the best in the

people that work with and report to them. Managing relationships well depends on an

understanding and awareness of the staff and of their talents, abilities, interests and

motives. It is also dependent upon effective social skills and emotional intelligence.

■ Encouraging and developing each member at work is essential for individual and

organisational health and is a major task of management. Recognising and improving

individual talent and potential is critical to ensure that the many roles and functions

of an organisation are achieved effectively. However, differences between individuals

can also be the source of problems and conflict. Personality clashes may occur; differ-

ences of attitudes and values may lead to polarisation and discrimination.

■ Improved self-awareness and accelerated development are essential to the educa-

tion of managers. Although psychologists do not agree in terms of the relative

importance of certain factors, there is much to be gained from both nomothetic and

idiographic approaches. Personality assessment techniques have been found to be

helpful in terms of self-knowledge and discovery as well as adding to the rapidly

enlarging repertoire of assessment centres. In mentoring an individual’s development,

an understanding of the causes of behaviour and past experiences can be helpful in

terms of future planning.

■ A major influencing factor affecting work performance is the ability of the

employee. Ensuring that the right people are selected for work and are able to use their

CHAPTER 9 INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

CRITICAL REFLECTIONS

‘OK, so it is important to understand that managing is all about people, and every person is an

individual in his or her own right. But manytheories and models about behaviour appear to

apply to people in general. Surely we should be more concerned with a study of differences

among individuals rather than similarities among people?’

What are your own views?

Among the factors that exert pressures on our personality formation are the culture in which we

are raised, our early conditioning, the norms among our family, friends, and social groups, and

other influences that we experience. The environment to which we are exposed plays a substan-

tial role in shaping our personalities.

Robbins, S. P. Organizational Behavior, Ninth edition, Prentice Hall International (2001), p. 93.

How would you describe the environmental factors which have helped shape your per-

sonality and how is this manifested in the work situation?

‘Freud’s personality theories have no practical use or value to the organisation.’

Debate.

SYNOPSIS

381

intelligence effectively is a critical personnel process, now helped by the appropriate

use of psychological tests. However, tests are not a panacea and can, if inappropriately

used, lead to a sense of false security.

■ Assessment of attitudes is vital in selecting potential employees and future man-

agers, and yet informal measures of observation are frequently used. Given the

difficulties of attitude measurement and doubts associated with predicting behaviour,

such assessment is fraught with problems. Managers may hold incorrect assumptions

and beliefs about their colleagues. Without a gauge to measure these attitudes, ineffec-

tive management decisions may be made. Attitudes can take on a permanency which is

maintained by the culture of the organisation and thus be very resistant to change.

Moreover, the power of attitudes should be recognised particularly with regard to influ-

encing newer members of the organisation and their development.

■ Understanding the ways in which working practices may have an unintended

adverse impact on women is a critical area of research to be conducted by organisa-

tions. Until practices are free of gender bias it is unlikely that women will have an

equal role in organisations. The differing approaches taken by psychologists offer com-

plementary perspectives from which to analyse individual behaviour. Practical

solutions to flexible work may produce mutual benefits for employees and employers,

but evaluation of these practices is a necessary outcome.

382

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

1 Identify the major ways in which individual differences are demonstrated at work. Discuss

strengths and limitations to the employer and employee of:

a people of the same age and/or race working together;

b people working different hours (flexi-time, part-time).

2 You are required to interview one person from your work or study group to produce an

assessment of their personality. What questions will you ask and how accurate do you

feel your assessment will be? What are some of the problems of using this method?

3 What are psychometric tests and when should they not be used?

4 Why are attitudes difficult to measure and change? How would you promote awareness

of the needs of students (or work colleagues) with disabilities? What would you do? What

reactions might you encounter?

5 Design a simple questionnaire to administer to your work/college colleagues on attitudes

towards reducing stress at work.

6 Hold a debate: ‘This house believes that low intelligence cannot be improved.’ Draw up

evidence for and against this statement. At the end of the debate, reflect on the strength

of emotional responses and consider the political arguments that have been addressed.

7 Analyse the evidence which suggests that men’s and women’s attitudes and motivations

to work are different.

8 List recommendations you would make to young Asian women about to embark on a

management career. Consider the differences you would make if you were to advise

young white men. Compare your list with others in the group.

9 ’Work-life balance is all about good management practice and sound business sense’. Is

it? Critically evaluate this statement.

10 Men and women need to work in partnership to establish equality in the workplace.

Critically discuss.

REVIEW AND DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Assignment 1

CHAPTER 9 INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

Role play the following situations:

SITUATION 1

Mumtaz has just completed her fast-track graduate programme and is now looking forward to

a Development Centre which will determine the next promotion step. She is anticipating an

international assignment.

She is already gaining a reputation for hard work and creative ideas and exudes confidence.

She is acutely aware that she has been the only female Asian on the programme. The organi-

sation’s dominant culture is white and male. A letter arrives from the HR Department with the

news that the Development Centre falls in the middle of Ramadan, a time when she needs to

fast and partake in regular prayer. She knows that the socialising aspects of the Development

Centres are important and that a formal lunch is prepared for each of the three days.

She is unsure whether she should inform her line manager of her anxieties, but she decides to

arrange a meeting.

■ Role-play the meeting in triads: playing the part of Mumtaz, the manager and the observer.

■ Take turns playing different roles, with different outcomes.

■ Discuss the feelings, attitudes and behaviours that were being portrayed.

SITUATION 2

Jordan is a highly successful salesman who works for an international IT organisation. As part

of the rewards package for sales staff, exotic prizes are offered to the best sales teams.

Jordan is part of the North West team, which has exceeded its targets over the last quarter.

The team is currently in the lead to win a trip on the Orient Express and a weekend in Venice.

The announcement is made and the team has won the prize. There is great joy and celebra-

tion in the office, especially as each team member can take their partner on the trip. Jordan is

gay but has not ‘come out’ at work. He wants to include his partner, but is uncertain of the

reaction of his colleagues. At the pub that evening he broaches the subject to two of his work

colleagues …

■ Role play the meeting with one observer.

■ Take turns playing different roles, with different outcomes.

■ Discuss the feelings, attitudes and behaviours that were being portrayed.

ASSIGNMENT

383

384

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

OBJECTIVES

Completing this exercise should help you to enhance the following skills:

Explore a range of issues concerned with individual differences.

Reflect on the nature of motivation and satisfaction of your needs.

Assess the strengths and weaknesses of using the repertory grid technique.

EXERCISE

Using Kelly’s repertory grid technique and Wilson’s framework (Table 9.6), you are required

to complete your own personal construct grid.

1Produce the elements and answer the following:

■ the job I do now; ■ the job I used to do (where appropriate);

■ an ideal job; ■ a job I would enjoy;

■ a job I would not enjoy; and ■ a job I would hate.

2 Develop the constructs

Write your answer at the top of each column. Now, select two elements (for example, 1

and 2) and compare with a third (for example, 6). State the way in which the two elements

are alike, and different from the third. Write your answer in the rows. These are your con-

structs. For example, I am now a lecturer (element 1) and I used to be a personnel officer

(element 2), and a job I would hate would be a factory operative (element 6). The ways in

which I see elements 1 and 2 as alike, and different from, 6 are in the intellectual demands

of the jobs. Select different triads until you have exhausted all possible constructs.

3 Score the constructs

Examine each construct in relation to the elements (jobs) you have described. Score

between 7 (high) and 1 (low).

4 Now compare:

–Your pattern of scores for element 1 and element 3. What does this tell you about your

current career and motivation?

–Your pattern of scores with the grid completed by an engineering craftsman as shown in

the section in the text on personality. (See Table 9.7.)

–Your constructs and elements with other colleagues.

DISCUSSION

■ How do you see the importance of constructs, goals and priorities in people’s lives?

■ What do you see as the meaning of work to the individual – central or peripheral goal?

■ Explain ways in which organisations may satisfy individual needs at work.

PERSONAL AWARENESS AND SKILLS EXERCISE

Visit our website www.booksites.net/mullins for further questions, annotated weblinks,

case material and Internet research material.